Abstract

Neural injury, inflammation, or diseases commonly and adversely affect micturition reflex function that is organized by neural circuits in the CNS and PNS. One neuropeptide receptor system, pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP; Adcyap1) and its cognate receptor, PAC1 (Adcyap1r1), have tissue-specific distributions in the lower urinary tract. PACAP and associated receptors are expressed in the LUT and exhibit changes in expression, distribution and function in preclinical animal models of bladder pain syndrome (BPS)/interstitial cystitis (IC), a chronic, visceral pain syndrome characterized by pain, and LUT dysfunction. Blockade of the PACAP/PAC1 receptor system reduces voiding frequency and somatic (e.g., hindpaw, pelvic) sensitivity in preclinical animal models and a transgenic mouse model that mirrors some clinical symptoms of BPS/IC. The PACAP/receptor system in micturition pathways may represent a potential target for therapeutic intervention to reduce LUT dysfunction following urinary bladder inflammation.

Keywords: NGF, cyclophosphamide, neuropeptides, cystometry, somatic sensation

Introduction

Micturition involves the filling and storage of urine in the bladder, and the periodic voiding of urine. Micturition is a fundamental, physiological process that is taken for granted until this behavior is altered. Storage and elimination functions involve the coordination of the structural features of the urinary bladder and complex neural pathways organized in the central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral nervous system (PNS) (Andersson and Arner, 2004; Merrill et al., 2016). It is perhaps because of the complexity of the neural circuitry underlying micturition that urinary bladder dysfunction often results following neural injury, inflammation and diseases that affect the nervous system and/or the urinary bladder. This mini-review addresses the involvement of the neuropeptide, PACAP and the PACAP selective receptor, PAC1, in micturition reflex function and plasticity following urinary bladder inflammation using preclinical models that mimic some of the symptoms of the chronic urologic pain syndrome, bladder pain syndrome (BPS)/interstitial cystitis (IC).

Lower Urinary Tract Pathways Supporting Micturition

The storage and elimination of urine is necessary to daily life. This is made possible by intricate neural signaling pathways that coordinate the functions of the urinary bladder and urethra (Andersson and Arner, 2004). The mature micturition reflex is a spinobulbospinal reflex pathway activated by mechanoreceptors in the urinary bladder wall (Beckel and Holstege, 2011). During the storage phase, solely the sympathetic system is active, which causes relaxation of the detrusor and contraction of the bladder neck and urethra; this leaves the bladder free to elongate and to accommodate increased volume. During the voiding phase, parasympathetic activation excites and contracts the detrusor muscle, while release from sympathetic activation relaxes the urethral sphincter (de Groat, 1990; 1993). The switch between the storage and voiding phases of the micturition reflex occurs when mechanoreceptor activity in the urinary bladder exceeds a threshold. Micturition can become compromised following injury or inflammation. For example, the barrier of the urinary bladder (i.e., the urothelium) can break down, allowing toxic substances to penetrate and to contribute to LUT symptoms (e.g., urinary urgency, frequency, voiding discomfort) (Andersson and Arner, 2004).

Bladder pain syndrome/interstitial cystitis

Background

Bladder pain syndrome (BPS)/interstitial cystitis (IC) is an urologic chronic pelvic pain syndrome characterized by pelvic-perceived pain, pressure or discomfort with at least one urinary symptom (Hanno and Sant, 2001). Other symptoms include nocturia, exaggeration of normal genitourinary sensations, and pain and discomfort with bladder fullness. The diversity of symptoms associated with BPS/IC suggests that the syndrome is heterogeneous and may reflect different subgroups with overlapping symptomology but unique etiology (Mullins et al., 2015).

Etiology

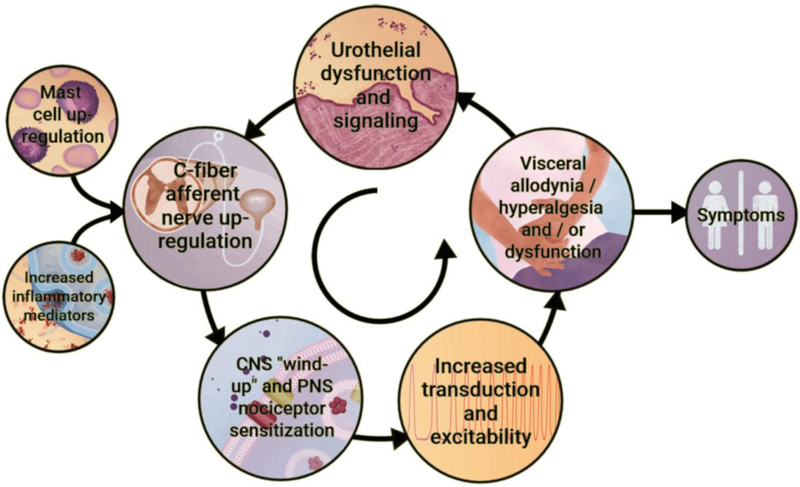

Although the etiology and pathogenesis of BPS/IC are unknown, infection, inflammation, autoimmune disorder, toxic urinary agents, urothelial dysfunction, mast cell involvement and neurogenic causes have been proposed (Driscoll and Teichman, 2001; Sant and Hanno, 2001; Parsons, 2007; Patnaik et al., 2017). Although the primary insult underlying BPS/IC is unknown, it has been suggested that the pathophysiology is a “vicious circle” involving uroepithelial dysfunction, inflammation, afferent nerve hyperexcitability and visceral hyperalgesia and allodynia (Sant et al., 2007) (Figure 1). Visceral inflammation remains a central pathological process in BPS/IC and has been suggested to underlie the development of LUT symptoms. Inflammation within the urinary bladder viscera is characterized by increased vasculature, mucosal irritation that may result in barrier dysfunction and infiltration of inflammatory mediators (Erickson et al., 1997; Grover et al., 2011) (Figure 1). The proliferation and activation of mast cells, in particular, has received considerable attention in the urinary bladder immune response (Sant et al., 2007). Mast cells secrete vasoactive chemicals to promote innate and auto-immunity and their increased activity has been widely demonstrated in BPS/IC (Kastrup et al., 1983; Enerback et al., 1989; Boucher et al., 1995; Theoharides et al., 1995). The subsequent exposure in the bladder interstitium to vasoactive chemicals, inflammatory mediators and neuropeptides from visceral inflammation may lead to afferent nerve hyperexcitability and neurogenic inflammation (Yoshimura and de Groat, 1999; Vizzard, 2001a; Yu and de Groat, 2008) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Potential etiologic cascade and pathogenesis underlying painful bladder syndrome (BPS)/interstitial cystitis (IC).

It is likely that BPS/IC has a multifactorial etiology that may act predominantly through one or more pathways resulting in the typical symptom-complex. There is a lack of consensus regarding the etiology or pathogenesis of BPS/IC but a number of proposals include a “leaky epithelium,” release of neuroactive compounds at the level of the urinary bladder with mast cell activation, “awakening” of C-fiber bladder afferents, and upregulation of inflammatory mediators including cytokines and chemotactic cytokines (chemokines). Inflammatory mediators can affect CNS and PNS neural circuitry including central “wind-up” and nociceptor sensitization resulting in chronic bladder pain and voiding dysfunction. BPS/IC is associated with diseases affecting other viscera and pelvic floors. See text for additional details. Figure adapted from (Sant et al., 2007; Gonzalez et al., 2014).

Allodynia and hyperalgesia

Pain is the hallmark symptom of BPS/IC and central to the diagnosis of BPS/IC together with the exclusion of other disorders (Fitzgerald et al., 2005). BPS/IC often involves two distinct pain-related symptoms: allodynia and hyperalgesia. Allodynia is characterized by a hypersensitive state in which normally innocuous stimuli (i.e., bladder fullness) causes pain and discomfort occur at lower volumes than normal. Under normal conditions, as the bladder fills, there is no conscious perception of bladder distension until a threshold volume is reached (Nazif et al., 2007). In BPS/IC, changes in bladder afferents lead to awareness of bladder filling much sooner than in normal circumstances, so there is discomfort and often pain with bladder distension that is reduced or eliminated with bladder emptying (Fitzgerald et al., 2005; Nazif et al., 2007). Hyperalgesia can also occur where noxious stimuli are perceived as even more painful (Persu et al., 2010). In BPS/IC, the sensitization of bladder afferents that occurs after insult leads to an increase in excitation that can contribute to an increase in pain sensation (Fitzgerald et al., 2005; Nazif et al., 2007) (Figure 1). Afferent nerve (Aδ and C-fibers) hyperexcitability increases input into the spinal cord that may eventually promote central sensitization or ‘wind-up’ (Sant et al., 2007). Central sensitization can lead to the loss of inhibition of dorsal horn neurons and a decrease in the threshold of nociceptors in the periphery, causing neurogenic inflammation, hyperalgesia, and dysreflexia symptoms that establish a self-perpetuating state that is classic in chronic visceral pain syndromes (Butrick, 2003)(Figure 1). This self-perpetuating state continues with mast cell degranulation, infiltration of mediators from uroepithelial dysfunction, and/or visceral inflammation that sustains peripheral and central sensitization that underlies visceral hyperalgesia/allodynia and symptoms of urinary frequency and urgency (Sant et al., 2007)(Figure 1).

We have hypothesized that pain associated with BPS/IC and changes in urinary bladder function (i.e., increased urinary frequency) involves an alteration of visceral sensation/bladder sensory physiology may be mediated by inflammatory changes in the urinary bladder. For example, neurotrophins (e.g., nerve growth factor, NGF) have been implicated in the peripheral sensitization of nociceptors (Lindsay and Harmar, 1989; Dray, 1995; Dinarello, 1997). Intravenous administration of a humanized monoclonal antibody that specifically inhibits NGF (tanezumab) in patients with BPS/IC demonstrates proof of concept by improving the global response assessment and reducing the urgency episode frequency (Evans et al., 2011).However, clinical trials involving systemic anti-NGF therapies for diverse pain conditions have halted enrollment due to incidence and risk of osteonecrosis (Evans et al., 2011). The need for additional LUT targets beyond NGF is clear. Additional NGF-mediated pleiotropic changes, including changes in neuropeptide expression (e.g., pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide, PACAP), may contribute to increases in urinary frequency and pelvic hypersensitivity in BPS/IC.

NGF signaling and nociception

NGF is a peptide that consists of a α, β and γ subunits that bind to TrkA (receptor tyrosine kinase A, tropomyosin-related kinase A) to initiate downstream effects. NGF binds to TrkA at the nerve terminal resulting in receptor dimerization, internalization and the formation of a signaling endosome. The endosome is then trafficked to the cell body via retrograde transport through the axon, where it continues to signal and induce long-term changes including: altering the expression of various receptors and other neuropeptides, synaptic reorganization, mediating neurotransmitter phenotype, increasing synaptic efficiency and controlling function in target organs (Levi-Montalcini et al., 1996; Huang and Reichardt, 2001; Pezet and McMahon, 2006; Mizumura and Murase, 2015).

NGF was the first neurotrophic factor to be identified and was initially found to play a role in the development of sympathetic neurons as well as sensory neurons involved with pain and temperature (Ritter et al., 1991; Levi-Montalcini et al., 1996; Apfel, 2001). Over the last two decades, NGF signaling has been shown to be a major factor in numerous pain conditions: (1) NGF levels are elevated in chronic pain conditions (Aloe et al., 1992; Iannone et al., 2002; Sarchielli et al., 2007); (2) NGF is synthesized and released following repeated tissue injury and subsequent inflammation (Paterson et al., 2009) and (3) NGF blockade decreases pain in acute and chronic pain conditions (Cattaneo, 2010). Notably, it has been determined that NGF plays a role in the development of hyperalgesia in response to urinary bladder inflammation following cystitis. Previous studies have implicated NGF in morphological and functional changes in the sensory and sympathetic neurons that innervate the urinary bladder (Dmitrieva et al., 1997; Clemow et al., 1998; Chuang et al., 2001; Hu et al., 2005; Guerios et al., 2006; Zvara and Vizzard, 2007; Guerios et al., 2008). Moreover, NGF has been detected in the urine and urinary bladder biopsies of women with BPS/IC (Lowe et al., 1997; Okragly et al., 1999) and increased NGF expression has been observed in micturition reflex pathways, spinal cord and peripheral ganglia in animal models of the disease (Dmitrieva et al., 1997; Clemow et al., 1998; Jaggar et al., 1999; Chuang et al., 2001; Hu et al., 2005; Guerios et al., 2006; Zvara and Vizzard, 2007; Guerios et al., 2008).

Neuropeptides in Micturition Reflex Pathways

Bladder afferents contain a variety of neuroactive compounds including neuropeptides: calcitonin-gene related peptide (CGRP), substance P (Sub P), vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP), pituitary adenylate cyclase- activating polypeptide (PACAP), cholecystokinin and enkephalins (Donovan et al., 1983; De Groat, 1986; Keast and De Groat, 1992; Vizzard et al., 1994; Vizzard, 2000c; 2001a). All of these neuropeptides, except CGRP, are predominantly expressed in small diameter (presumably C-fiber) afferents (Donovan et al., 1983; De Groat, 1986; Keast and De Groat, 1992; Vizzard et al., 1994; Vizzard, 2000c; 2001a). An increase in NGF expression in DRG neurons can induce increased production of neuropeptides (e.g., Sub P, CGRP and PACAP) and alter sensory transduction (Donnerer et al., 1992; Woolf et al., 1997). The following sections will address the expression, distribution and functional role(s) of PACAP/PAC1 in LUT pathways in control conditions, in a transgenic mouse model with chronic urothelial overexpression of NGF, and following urinary bladder inflammation induced by the anti-neoplastic agent, cyclophosphamide (CYP).

PACAP and associated receptors

PACAP is a member of the vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP)/secretin/glucagon family of hormones, originally isolated from the hypothalamus because of its ability to stimulate anterior pituitary adenylate cyclase activity (Ogi et al., 1990; Arimura, 1998). PACAP38 and PACAP27 are the two mature, ∝-amidated forms of PACAP that play roles in cell signaling and neuroendocrine functions in the CNS and PNS (Kimura et al., 1990; Ohkubo et al., 1992; Okazaki et al., 1995; Arimura, 1998; Braas et al., 1998). PACAP and VIP exert a variety of diverse effects by binding to three distinct G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs): PAC1, VPAC1, and VPAC2 that exhibit tissue- and cell-type specific expression and function (Ishihara et al., 1992; Hashimoto et al., 1993; Hosoya et al., 1993; Lutz et al., 1993; Spengler et al., 1993; Inagaki et al., 1994; May and Braas, 1995; Braas and May, 1996; Beaudet et al., 1998; Braas et al., 1998; May et al., 1998; Braas and May, 1999; DiCicco-Bloom et al., 2000). When PACAP binds to PAC1, the GPCR is internalized via endocytosis and endosomal signaling leads to diverse downstream effects (May and Parsons, 2017).

PACAP expression and function

PACAP is expressed in peripheral autonomic and sensory neurons and can exert differential downstream effects depending on the receptor subtype expression in the target tissue. Among its diverse functions, PACAP has critical roles in maintaining homeostasis in a multitude of physiological systems, including: endocrine hormone production and secretion, cardiovascular responses, glucose metabolism, gastrointestinal motility, micturition, nociception, and germ cell development (Vaudry et al., 2009). In addition, PACAP regulates a variety of central functions including: feeding/satiety, autonomic responses, nociceptive sensitivity, cognition and learning/memory, and stress-associated behaviors including stress-related psychopathologies (Ressler et al., 2011; Hammack and May, 2015; Pohlack et al., 2015). PACAP or PAC1 receptor deficient mice have given additional insights into the functional significance of PACAP/PAC1 signaling. PACAP or PAC1 receptor deficient mice exhibit blunted anxiety-like behavior, show autonomic and HPA axis dysregulation to stress challenges, and fail to develop nociceptive hypersensitivity to inflammatory pain (Hashimoto et al., 2001; Jongsma Wallin et al., 2001; Otto et al., 2001; Girard et al., 2006; Stroth and Eiden, 2010; Tsukiyama et al., 2011; Hattori et al., 2012; Botz et al., 2013). In human studies, altered PACAP levels and PAC1 receptor polymorphism have been associated with posttraumatic stress disorder (Ressler et al., 2011). Recent studies also suggest an overlap in PACAP expression and involvement in supraspinal neural circuitry underlying pain and anxiety/stress behaviors (Missig et al., 2014; Missig et al., 2017).

Pre-clinical animal models

Cyclophosphamide (CYP)-induced cystitis

CYP-induced bladder inflammation has been extensively used in our laboratory to study BPS/IC using different protocols to model acute (4 hr), intermediate (48 hr) and more chronic (8–10 days) durations of urinary bladder inflammation. Acrolein, the metabolite of CYP, accumulates in the urinary bladder and produces toxic effects, including: edema, ulceration, necrosis, petechial hemorrhage and hemorrhagic cystitis (Batista et al., 2006). CYP treatment in mice and rats is associated with increased referred somatic sensitivity (Guerios et al., 2008; Studeny et al., 2008; Cheppudira et al., 2009). CYP-induced bladder inflammation has also resulted in changes in the inflammatory milieu of the urinary bladder, including the expression and function of cytokines, chemokines (Arms et al., 2010) and NGF (Vizzard, 2000a). CYP-induced bladder inflammation (Cox, 1979; Maggi et al., 1992) produces changes in urinary bladder function that is characterized by increases in voiding frequency, non-voiding bladder contractions during the filling phase, and changes in micturition pressures (Vizzard, 2000b; 2001b; Qiao and Vizzard, 2002; 2004). The inflammatory and functional changes exhibited in rodents following CYP treatment mimic some of the signs and symptoms of the clinical syndrome BPS/IC making it a valuable and reproducible model of clinical disease to evaluate specific hypotheses related to the etiology, pathophysiology and underlying mechanisms of BPS/IC.

Chronic Urothelial Overexpression of NGF (NGF-OE) in Mice

We characterized a transgenic mouse model of urothelium-specific NGF-OE that represents a novel approach to exploring the role of NGF in urinary bladder inflammation and sensory function (Schnegelsberg et al., 2010). NGF-OE mice exhibit an increase in urinary frequency and the presence of non-voiding bladder contractions (NVCs) as well as referred pelvic hypersensitivity (Schnegelsberg et al., 2010). NGF- OE mice may represent a useful animal model of BPS/IC because the increased NGF content and other sensory and local mast cell inflammatory changes observed in the urinary bladders of these mice are consistent with changes observed with the clinical presentation of BPS/ICs. Clinically, increased NGF levels have been detected in the bladder urothelium of patients with BPS/IC (Lowe et al., 1997). Elevated NGF levels were also detected in the urine of patients with BPS/IC or overactive bladder symptoms associated with detrusor overactivity (DO), stress urinary incontinence, or bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) (Andersson, 2002; Kim et al., 2004; Kim et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2006; Liu and Kuo, 2008; 2009). Patients with DO who responded to treatment showed reduced urinary NGF levels (Liu and Kuo, 2007; 2008). Our findings support and extend many previous studies in rodents demonstrating involvement of NGF in altered bladder sensory function and the development of referred hyperalgesia in response to bladder inflammation (Dmitrieva and McMahon, 1996; Dmitrieva et al., 1997; Jaggar et al., 1999; Lamb et al., 2004; Hu et al., 2005; Guerios et al., 2006; Yoshimura et al., 2006; Zvara and Vizzard, 2007; Guerios et al., 2008).

PACAP and Micturition Pathways

PACAP (Adcyap1) and its cognate receptor, PAC1 (Adcyap1r1), have tissue-specific distributions in the LUT. Dense PACAP expression is present in LUT pathways in the CNS and PNS including expression in the urinary bladder. PACAP- immunoreactivity is exhibited throughout the urinary bladder in nerve fibers in the urinary bladder smooth muscle, suburothelial nerve plexus, and surrounding blood vessels (Fahrenkrug and Hannibal, 1998). In neonatal rats treated with the TRPV1-agonist and C-fiber neurotoxin, capsaicin, PACAP expression was significantly reduced in the urinary tract (i.e., ureter, bladder, and urethra), suggesting these PACAP-immunoreactive fibers are derived from small diameter, C-fiber afferents (Fahrenkrug and Hannibal, 1998). In the DRG, PACAP expression was present in small and medium sized DRG neurons including bladder afferent cells. Increases in PACAP expression in lumbosacral DRG are observed after nerve injury, inflammation, spinal cord injury or CYP-induced cystitis (Zhang et al., 1995; Zhang et al., 1996; Larsen et al., 1997; Moller et al., 1997; Vizzard, 2000c).

PACAP knockout (−/−) mice exhibit bladder dysfunction and altered somatic sensitivity

PACAP(−/−) mice exhibited an increase in bladder mass with a significantly thicker lamina propria and detrusor smooth muscle but the urothelium was unchanged (May and Vizzard, 2010). Using functional bladder testing, PACAP(−/−) mice exhibited increased bladder capacity, voided volume and intervals between voiding events (i.e., intercontraction interval) with significantly increased detrusor contraction duration and large residual volume (May and Vizzard, 2010). Although wildtype mice respond to intravesical infusion of acetic acid (0.5%) with a decrease in voided volume and intercontraction interval, PACAP(−/−) mice do not exhibit any changes in bladder function (May and Vizzard, 2010) consistent with a nociceptive response to bladder irritation being mediated, in part, by PACAP-immunoreactive C-fiber bladder afferents. In response to somatic sensitivity testing with calibrated von Frey filaments, PACAP(−/−) mice were less sensitive to hindpaw and pelvic stimulation compared to control mice (May and Vizzard, 2010). These results suggest that PACAP gene disruption contributes to changes in bladder morphology and function, and somatic and visceral sensation.

Functional Expression of PAC1 receptors in rat urothelium

Activation of PAC1 receptors by PACAP27, PACAP38 and VIP to cultured urothelial cells releases ATP, which may activate purinergic receptors expressed on adjacent sensory nerve fibers in the suburothelial plexus as well as on other tissues including detrusor smooth muscle and interstitial cells in the lamina propria (Girard et al., 2008). PAC1 receptor antagonism blocked ATP release (Girard et al., 2008) suggesting that PACAP signaling through PAC1 receptors may regulate micturition reflex function at the level of the urothelium (Girard et al., 2008).

PACAP Expression and Function in Micturition Reflexes following CYP-induced cystitis

PACAP plays a role in urinary bladder dysfunction observed in rodents following CYP-induced cystitis (Vizzard, 2000c; Braas et al., 2006; Herrera et al., 2006; Girard et al., 2008). PACAP and its receptor, PAC1, are expressed throughout the micturition reflex circuitry (Braas et al., 2006), and this expression increased following CYP-induced cystitis. In the spinal cord, PACAP- immunoreactivity dramatically increased in rostral lumbar (L1-L2) spinal cord regions (Vizzard, 2000c), as well as in the lower lumbosacral (L6-S1) spinal cord regions involved in micturition reflexes (Herrera et al., 2006). Intermediate and chronic CYP treatments significantly increased PACAP transcript and protein expression in lumbosacral DRG (Vizzard, 2000c; Girard et al., 2008). CYP-induced cystitis also significantly increased PACAP expression in bladder afferent cells in lumbosacral DRG that were retrogradely labeled from the urinary bladder (Vizzard, 2000c). Intermediate and chronic CYP treatments similarly increased PACAP and/or PAC1 receptor transcript expression in the urothelium and detrusor smooth muscle (Girard et al., 2008). We have recently extended these observations by examining the effects of CYP-induced bladder inflammation (4 h, 48 h, chronic) on LUT pathways in PACAP promoter-dependent BAC transgenic mice (Vizzard et al., unpublished observations). In control animals, low expression of PACAP-EGFP+ fibers was present in the superficial dorsal horn (L1, L2, L4-S1). After CYP-induced cystitis, PACAP-EGFP+ cells increased in spinal segments and dorsal root ganglia (L1, L2, L6, S1) involved in micturition. The density of PACAP-EGFP+ nerve fibers was increased in the superficial laminae (I-II) of the L1, L2, L6, S1 dorsal horn and in the lateral collateral pathway in L6-S1 spinal cord. After cystitis, PACAP-EGFP+ cells and nerve fibers were present in many supraspinal regions, including: locus coeruleus, Barrington’s nucleus or the pontine micturition center, rostral ventrolateral medulla, PAG, raphe, and amygdala. Following cystitis, the number of PACAP-EGFP+ urothelial cells increased with duration of cystitis. PACAP expression in LUT pathways after cystitis may play a role in altered visceral sensation and/or increased voiding frequency.

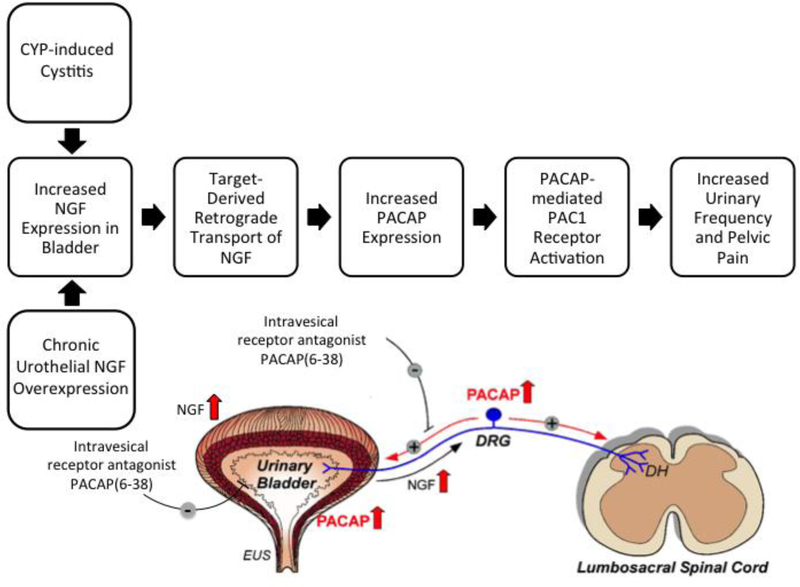

Functional studies with a PAC1 receptor antagonist have demonstrated a role for PACAP/PAC1 signaling in micturition reflex pathways following urinary bladder inflammation. Intrathecal or intravesical administration of the PAC1 receptor antagonist, PACAP(6–38), increased bladder capacity, reduced voiding frequency and decreased the number and amplitude of non-voiding bladder contractions in CYP-treated rats (Braas et al., 2006)(Figure 2). The expression and upregulation of PACAP/PAC1 in LUT pathways and the functional benefit of PAC1 receptor blockade to the urinary bladder in preclinical animal models suggest that targeting PACAP/PAC1 signaling in micturition pathways may have translational benefit to the clinical syndrome, BPS/IC (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Blockade of the PACAP/receptor system in micturition reflexes is a potential strategy to improve bladder function and reduce pelvic pain following urinary bladder inflammation.

The CYP-induced bladder inflammation model in rodents and the transgenic mouse model of chronic urothelial overexpression of NGF (NGF-OE) are essential to determine underlying mechanisms contributing to urinary bladder dysfunction and pelvic pain in the clinical syndrome BPS/IC. Both models are associated with changes in NGF expression in the urinary bladder that can result in changes in the urinary bladder and be retrogradely transported to lumbosacral dorsal root ganglia (DRG). PACAP and PAC1 receptor exhibit neuroplastic changes in expression and function with CYP-induced bladder inflammation and increased NGF expression in the urinary bladder. Intravesical instillation of the PAC1 receptor antagonist, PACAP (6–38), reduces voiding frequency and somatic sensitivity. Blockade of PAC1 in micturition reflexes may represent a novel therapeutic intervention to improve urinary bladder function and reduce referred, somatic pain. DH, dorsal horn; EUS, external urethral sphincter. Figure adapted from (Girard et al., 2017).

NGF-OE and PACAP signaling

PACAP/PAC1 expression and function has also been evaluated using the NGF-OE mouse that exhibits chronic urothelial overexpression of NGF. PAC1 receptor transcript expression increased in the urothelium of NGF-OE mice whereas PACAP transcript expression decreased in the urothelium of NGF-OE mice (Girard, et al., 2012). Using conscious cystometry, functional studies demonstrated that chronic NGF overexpression in the urothelium increased voiding frequency, non-voiding contractions and referred somatic (i.e., pelvic) sensitivity (Schnegelsberg et al., 2010). Additionally, the intravesical infusion of a PAC1 antagonist, PACAP (6–38), significantly increased the time between voiding events (i.e., intercontraction interval) and the void volume in NGF-OE mice. PACAP (6–38) also significantly reduced pelvic sensitivity in NGF-OE mice (Girard, et al., 2016) (Figure 2). In conclusion, PACAP signaling contributes to the hyperalgesia and increased voiding frequency in NGF-OE mice.

Pleiotropic changes in neuropeptide/receptor systems in LUT pathways in NGF-OE mice

Chronic urothelial overexpression of NGF (NGF-OE) in mice produces changes in PACAP/receptor expression in micturition reflex pathways. PAC1 receptor transcript and PAC1- immunoreactivity were significantly increased in the urothelium of NGF-OE mice whereas PACAP transcript expression and PACAP-immunoreactivity were decreased in the urothelium of NGF-OE mice (Girard et al., 2010). In contrast, VPAC1 receptor transcript was decreased in both urothelium and detrusor smooth muscle of NGF-OE mice (Girard et al., 2010). VPAC2 receptor transcript was significantly increased in the detrusor smooth muscle in NGF-OE mice (Girard et al., 2010). NGF-OE mice exhibit additional changes in PACAP and associated receptors expression in LUT pathways that may also contribute to altered urinary bladder function in NGF-OE mice.

NGF and PACAP Interactions

Both CYP-induced cystitis in rodents and the NGF-OE mouse model exhibit increased expression of NGF in LUT pathways (e.g., DRG, urinary bladder) with subsequent changes in the expression and function of PACAP/PAC1 signaling in LUT pathways (Figure 2). Reciprocal regulatory interactions between NGF and PACAP have previously been demonstrated in pheochromocytoma (PC)12 cells and sensory ganglia with NGF acting a positive regulator of PACAP expression in DRG cells (Jongsma Wallin et al., 2001). In rat PC12 cells, both NGF and PACAP can induce PC differentiation into a neuronal phenotype (Grumolato et al., 2003). In addition, the neurotrophins, NGF and/or brain-derived neurotrophic factor facilitated expression of the PAC1 receptor in CNS neurons (i.e., cerebellar granule cells) and PC12 cells (Jamen et al., 2002). In complementary studies, PACAP upregulated expression and/or phosphorylation of neurotrophin receptors (e.g., TrkA, TrkB, TrkC) in PC12 cells, CNS neurons (i.e., hippocampal neurons) (Lee et al., 2002) and sympathetic neuroblasts (DiCicco- Bloom et al., 2000). In some contexts, reciprocal regulation of PACAP and NGF signaling pathways may be a feed-forward mechanism to amplify critical, physiological processes (e.g., survival or differentiation) during neuronal development or regeneration. In the context of urinary bladder inflammation, a feed-forward mechanism may be damaging by amplifying painful signals (i.e., allodynia and hyperalgesia) and target organ dysfunction (Figure 2).

Summary and Conclusions

BPS/IC is a chronic, inflammatory pain syndrome that affects both women and men with few effective treatments perhaps due to the heterogeneous nature of the disease. New treatment options, evaluated using preclinical models with signs and symptoms common to the clinical presentation of BPS/IC, are needed. Using the CYP-induced cystitis model in rodents and a transgenic mouse model with chronic, urothelial overexpression of NGF, blockade of the PACAP/PAC1 signaling pathway reduced urinary frequency and referred, somatic sensitivity (Figure 2). In the context of urinary bladder inflammation, blockade of peptide/receptor systems including PACAP/PAC1 and other systems (e.g. CGRP/CGRP receptor) expressed in bladder sensory neurons should be considered as potential targets for pharmacological intervention with the anticipation of pain relief and normalization of urinary bladder function.

Acknowledgments

Grants

Research described herein was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants to RO1- DK051369 (MAV), RO1-DK060481 (MAV). This publication was also made possible by NIH Grants: 5 P30 RR032135 from the COBRE Program of the National Center for Research Resources and 8 P30 GM103498 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

The funding entity, NIH, had no role in the studies described including: design, data collection and analysis of studies performed in the Vizzard laboratory, decision to publish or preparation of the review. The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIH.

Abbreviations

- AT

Adenosine triphosphate

- BOO

Bladder outlet obstruction

- BPS

Bladder pain syndrome

- CGRP

Calcitonin-gene related peptide

- CNS

Central nervous system

- CYP

Cyclophosphamide

- DO

Detrusor overactivity

- DRG

Dorsal root ganglion

- GPCR

G-protein-coupled receptor

- HPA

Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal

- hr

hours

- IC

Interstitial cystitis

- LUT

Lower urinary tract

- NGF

Nerve growth factor

- NGF-OE

Nerve growth factor overexpression

- NVC

Non-voiding bladder contraction

- PAC1

PACAP type I receptor

- PACAP

Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide

- PAG

Periaqueductal grey

- PC

pheochromocytoma

- PMC

Pontine micturition center

- PNS

Peripheral nervous system

- Sub P

Substance P

- TrkA

Receptor tyrosine kinase A, tropomyosin-related kinase A

- TrkB

Receptor tyrosine kinase B, tropomyosin-related kinase B

- TrkC

Receptor tyrosine kinase C, tropomyosin-related kinase C

- VIP

Vasoactive intestinal polypeptide

- VPAC1

VIP receptor 1

- VPAC2

VIP receptor 2

Footnotes

Studies involving animal research

The studies described from the Vizzard laboratory were performed in accordance with institutional and national guidelines and regulations. The University of Vermont Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all experimental protocols involving animal use. Animal care was under the supervision of the University of Vermont’s Office of Animal Care Management in accordance with the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC) and National Institutes of Health guidelines. All efforts were made to minimize the potential for animal pain, stress or distress.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research described from the Vizzard laboratory were conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Aloe L, Tuveri MA, Carcassi U, and Levi-Montalcini R (1992). Nerve growth factor in the synovial fluid of patients with chronic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 35(3), 351–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson KE (2002). Bladder activation: afferent mechanisms. Urology 59(5 Suppl 1), 43–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson KE, and Arner A (2004). Urinary bladder contraction and relaxation: physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev 84(3), 935–986. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00038.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apfel SC (2001). Neurotrophic factor therapy--prospects and problems. Clin Chem Lab Med 39(4), 351–355. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2001.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arimura A (1998). Perspectives on pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide (PACAP) in the neuroendocrine, endocrine, and nervous systems. Jpn J Physiol 48(5), 301–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arms L, Girard BM, and Vizzard MA (2010). Expression and function of CXCL12/CXCR4 in rat urinary bladder with cyclophosphamide-induced cystitis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 298(3), F589–600. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00628.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batista CK, Brito GA, Souza ML, Leitao BT, Cunha FQ, and Ribeiro RA (2006). A model of hemorrhagic cystitis induced with acrolein in mice. Braz J Med Biol Res 39(11), 1475– 1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaudet MM, Braas KM, and May V (1998). Pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide (PACAP) expression in sympathetic preganglionic projection neurons to the superior cervical ganglion. J Neurobiol 36(3), 325–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckel JM, and Holstege G (2011). Neuroanatomy of the lower urinary tract. Handb Exp Pharmacol (202), 99–116. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-16499-6_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botz B, Imreh A, Sandor K, Elekes K, Szolcsanyi J, Reglodi D, et al. (2013). Role of Pituitary Adenylate-Cyclase Activating Polypeptide and Tac1 gene derived tachykinins in sensory, motor and vascular functions under normal and neuropathic conditions. Peptides 43, 105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher W, el-Mansoury M, Pang X, Sant GR, and Theoharides TC (1995). Elevated mast cell tryptase in the urine of patients with interstitial cystitis. Br J Urol 76(1), 94–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braas KM, and May V (1996). Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptides, PACAP-38 and PACAP-27, regulation of sympathetic neuron catecholamine, and neuropeptide Y expression through activation of type I PACAP/VIP receptor isoforms. Ann N Y Acad Sci 805, 204–216; discussion 217–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braas KM, and May V (1999). Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptides directly stimulate sympathetic neuron neuropeptide Y release through PAC(1) receptor isoform activation of specific intracellular signaling pathways. J Biol Chem 274(39), 27702–27710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braas KM, May V, Harakall SA, Hardwick JC, and Parsons RL (1998). Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide expression and modulation of neuronal excitability in guinea pig cardiac ganglia. J Neurosci 18(23), 9766–9779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braas KM, May V, Zvara P, Nausch B, Kliment J, Dunleavy JD, et al. (2006). Role for pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide in cystitis-induced plasticity of micturition reflexes. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 290(4), R951–962. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00734.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butrick CW (2003). Interstitial cystitis and chronic pelvic pain: new insights in neuropathology, diagnosis, and treatment. Clin Obstet Gynecol 46(4), 811–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattaneo A (2010). Tanezumab, a recombinant humanized mAb against nerve growth factor for the treatment of acute and chronic pain. Curr Opin Mol Ther 12(1), 94–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheppudira BP, Girard BM, Malley SE, Dattilio A, Schutz KC, May V, et al. (2009). Involvement of JAK-STAT signaling/function after cyclophosphamide-induced bladder inflammation in female rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 297(4), F1038–1044. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00110.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang YC, Fraser MO, Yu Y, Chancellor MB, de Groat WC, and Yoshimura N (2001). The role of bladder afferent pathways in bladder hyperactivity induced by the intravesical administration of nerve growth factor. J Urol 165(3), 975–979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemow DB, Steers WD, McCarty R, and Tuttle JB (1998). Altered regulation of bladder nerve growth factor and neurally mediated hyperactive voiding. Am J Physiol 275(4 Pt 2), R1279–1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox PJ (1979). Cyclophosphamide cystitis--identification of acrolein as the causative agent. Biochemical Pharmacology 28, 2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Groat WC (1986). Spinal cord projections and neuropeptides in visceral afferent neurons. Prog Brain Res 67, 165–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Groat WC (1990). Central neural control of the lower urinary tract. Ciba Found Symp 151, 27–44; discussion 44–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Groat WC (1993). Anatomy and physiology of the lower urinary tract. Urol Clin North Am 20(3), 383–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiCicco-Bloom E, Deutsch PJ, Maltzman J, Zhang J, Pintar JE, Zheng J, et al. (2000). Autocrine expression and ontogenetic functions of the PACAP ligand/receptor system during sympathetic development. Dev Biol 219(2), 197–213. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinarello CA (1997). Role of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines during inflammation: experimental and clinical findings. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents 11(3), 91–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dmitrieva N, and McMahon SB (1996). Sensitisation of visceral afferents by nerve growth factor in the adult rat. Pain 66(1), 87–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dmitrieva N, Shelton D, Rice AS, and McMahon SB (1997). The role of nerve growth factor in a model of visceral inflammation. Neuroscience 78(2), 449–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnerer J, Schuligoi R, and Stein C (1992). Increased content and transport of substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide in sensory nerves innervating inflamed tissue: evidence for a regulatory function of nerve growth factor in vivo. Neuroscience 49(3), 693–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan MK, Winternitz SR, and Wyss JM (1983). An analysis of the sensory innervation of the urinary system in the rat. Brain Res Bull 11(3), 321–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dray A (1995). Inflammatory mediators of pain. Br J Anaesth 75(2), 125–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll A, and Teichman JM (2001). How do patients with interstitial cystitis present? J Urol 166(6), 2118–2120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enerback L, Fall M, and Aldenborg F (1989). Histamine and mucosal mast cells in interstitial cystitis. Agents Actions 27(1–2), 113–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson DR, Belchis DA, and Dabbs DJ (1997). Inflammatory cell types and clinical features of interstitial cystitis. J Urol 158(3 Pt 1), 790–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans RJ, Moldwin RM, Cossons N, Darekar A, Mills IW, and Scholfield D (2011). Proof of concept trial of tanezumab for the treatment of symptoms associated with interstitial cystitis. J Urol 185(5), 1716–1721. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.12.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahrenkrug J, and Hannibal J (1998). PACAP in visceral afferent nerves supplying the rat digestive and urinary tracts. Ann N Y Acad Sci 865, 542–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald MP, Koch D, and Senka J (2005). Visceral and cutaneous sensory testing in patients with painful bladder syndrome. Neurourol Urodyn 24(7), 627–632. doi: 10.1002/nau.20178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard BA, Lelievre V, Braas KM, Razinia T, Vizzard MA, Ioffe Y, et al. (2006). Noncompensation in peptide/receptor gene expression and distinct behavioral phenotypes in VIP- and PACAP-deficient mice. J Neurochem 99(2), 499–513. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard BM, Malley SE, Braas KM, May V, and Vizzard MA (2010). PACAP/VIP and receptor characterization in micturition pathways in mice with overexpression of NGF in urothelium. J Mol Neurosci 42(3), 378–389. doi: 10.1007/s12031-010-9384-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard BM, Tooke K, and Vizzard MA (2017). PACAP/Receptor System in Urinary Bladder Dysfunction and Pelvic Pain Following Urinary Bladder Inflammation or Stress. Front Syst Neurosci 11, 90. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2017.00090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard BM, Wolf-Johnston A, Braas KM, Birder LA, May V, and Vizzard MA (2008). PACAP-mediated ATP release from rat urothelium and regulation of PACAP/VIP and receptor mRNA in micturition pathways after cyclophosphamide (CYP)-induced cystitis. J Mol Neurosci 36(1–3), 310–320. doi: 10.1007/s12031-008-9104-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez EJ, Arms L, and Vizzard MA (2014). The role(s) of cytokines/chemokines in urinary bladder inflammation and dysfunction. Biomed Res Int 2014, 120525. doi: 10.1155/2014/120525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover S, Srivastava A, Lee R, Tewari AK, and Te AE (2011). Role of inflammation in bladder function and interstitial cystitis. Ther Adv Urol 3(1), 19–33. doi: 10.1177/1756287211398255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grumolato L, Louiset E, Alexandre D, Ait-Ali D, Turquier V, Fournier A, et al. (2003). PACAP and NGF regulate common and distinct traits of the sympathoadrenal lineage: effects on electrical properties, gene markers and transcription factors in differentiating PC12 cells. Eur J Neurosci 17(1), 71–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerios SD, Wang ZY, and Bjorling DE (2006). Nerve growth factor mediates peripheral mechanical hypersensitivity that accompanies experimental cystitis in mice. Neurosci Lett 392(3), 193–197. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerios SD, Wang ZY, Boldon K, Bushman W, and Bjorling DE (2008). Blockade of NGF and trk receptors inhibits increased peripheral mechanical sensitivity accompanying cystitis in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 295(1), R111–122. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00728.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammack SE, and May V (2015). Pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide in stress- related disorders: data convergence from animal and human studies. Biol Psychiatry 78(3), 167–177. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanno PM, and Sant GR (2001). Clinical highlights of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases/Interstitial Cystitis Association scientific conference on interstitial cystitis. Urology 57(6 Suppl 1), 2–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto H, Ishihara T, Shigemoto R, Mori K, and Nagata S (1993). Molecular cloning and tissue distribution of a receptor for pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide. Neuron 11(2), 333–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto H, Shintani N, Tanaka K, Mori W, Hirose M, Matsuda T, et al. (2001). Altered psychomotor behaviors in mice lacking pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98(23), 13355–13360. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231094498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattori S, Takao K, Tanda K, Toyama K, Shintani N, Baba A, et al. (2012). Comprehensive behavioral analysis of pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) knockout mice. Front Behav Neurosci 6, 58. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2012.00058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera GM, Braas KM, May V, and Vizzard MA (2006). PACAP enhances mouse urinary bladder contractility and is upregulated in micturition reflex pathways after cystitis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1070, 330–336. doi: 10.1196/annals.1317.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosoya M, Onda H, Ogi K, Masuda Y, Miyamoto Y, Ohtaki T, et al. (1993). Molecular cloning and functional expression of rat cDNAs encoding the receptor for pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide (PACAP). Biochem Biophys Res Commun 194(1), 133–143. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu VY, Zvara P, Dattilio A, Redman TL, Allen SJ, Dawbarn D, et al. (2005). Decrease in bladder overactivity with REN1820 in rats with cyclophosphamide induced cystitis. J Urol 173(3), 1016–1021. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000155170.15023.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang EJ, and Reichardt LF (2001). Neurotrophins: roles in neuronal development and function. Annu Rev Neurosci 24, 677–736. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iannone F, De Bari C, Dell’Accio F, Covelli M, Patella V, Lo Bianco G, et al. (2002). Increased expression of nerve growth factor (NGF) and high affinity NGF receptor (p140 TrkA) in human osteoarthritic chondrocytes. Rheumatology (Oxford) 41(12), 1413–1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki N, Yoshida H, Mizuta M, Mizuno N, Fujii Y, Gonoi T, et al. (1994). Cloning and functional characterization of a third pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide receptor subtype expressed in insulin-secreting cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 91(7), 2679–2683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara T, Shigemoto R, Mori K, Takahashi K, and Nagata S (1992). Functional expression and tissue distribution of a novel receptor for vasoactive intestinal polypeptide. Neuron 8(4), 811–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaggar SI, Scott HC, and Rice AS (1999). Inflammation of the rat urinary bladder is associated with a referred thermal hyperalgesia which is nerve growth factor dependent. Br J Anaesth 83(3), 442–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamen F, Bouschet T, Laden JC, Bockaert J, and Brabet P (2002). Up-regulation of the PACAP type-1 receptor (PAC1) promoter by neurotrophins in rat PC12 cells and mouse cerebellar granule cells via the Ras/mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade. J Neurochem 82(5), 1199–1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jongsma Wallin H, Danielsen N, Johnston JM, Gratto KA, Karchewski LA, and Verge VM (2001). Exogenous NT-3 and NGF differentially modulate PACAP expression in adult sensory neurons, suggesting distinct roles in injury and inflammation. Eur J Neurosci 14(2), 267–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastrup J, Hald T, Larsen S, and Nielsen VG (1983). Histamine content and mast cell count of detrusor muscle in patients with interstitial cystitis and other types of chronic cystitis. Br J Urol 55(5), 495–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keast JR, and De Groat WC (1992). Segmental distribution and peptide content of primary afferent neurons innervating the urogenital organs and colon of male rats. J Comp Neurol 319(4), 615–623. doi: 10.1002/cne.903190411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JC, Kim DB, Seo SI, Park YH, and Hwang TK (2004). Nerve growth factor and vanilloid receptor expression, and detrusor instability, after relieving bladder outlet obstruction in rats. BJU Int 94(6), 915–918. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-4096.2003.05059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JC, Park EY, Hong SH, Seo SI, Park YH, and Hwang TK (2005). Changes of urinary nerve growth factor and prostaglandins in male patients with overactive bladder symptom. Int J Urol 12(10), 875–880. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2005.01140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JC, Park EY, Seo SI, Park YH, and Hwang TK (2006). Nerve growth factor and prostaglandins in the urine of female patients with overactive bladder. J Urol 175(5), 1773–1776; discussion 1776. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00992-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura C, Ohkubo S, Ogi K, Hosoya M, Itoh Y, Onda H, et al. (1990). A novel peptide which stimulates adenylate cyclase: molecular cloning and characterization of the ovine and human cDNAs. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 166(1), 81–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb K, Gebhart GF, and Bielefeldt K (2004). Increased nerve growth factor expression triggers bladder overactivity. J Pain 5(3), 150–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen JO, Hannibal J, Knudsen SM, and Fahrenkrug J (1997). Expression of pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) in the mesencephalic trigeminal nucleus of the rat after transsection of the masseteric nerve. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 46(1–2), 109–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee FS, Rajagopal R, Kim AH, Chang PC, and Chao MV (2002). Activation of Trk neurotrophin receptor signaling by pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptides. J Biol Chem 277(11), 9096–9102. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107421200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi-Montalcini R, Skaper SD, Dal Toso R, Petrelli L, and Leon A (1996). Nerve growth factor: from neurotrophin to neurokine. Trends Neurosci 19(11), 514–520. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(96)10058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay RM, and Harmar AJ (1989). Nerve growth factor regulates expression of neuropeptide genes in adult sensory neurons. Nature 337(6205), 362–364. doi: 10.1038/337362a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu HT, and Kuo HC (2007). Intravesical botulinum toxin A injections plus hydrodistension can reduce nerve growth factor production and control bladder pain in interstitial cystitis. Urology 70(3), 463–468. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu HT, and Kuo HC (2008). Urinary nerve growth factor levels are increased in patients with bladder outlet obstruction with overactive bladder symptoms and reduced after successful medical treatment. Urology 72(1), 104–108; discussion 108. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.01.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu HT, and Kuo HC (2009). Urinary nerve growth factor levels are elevated in patients with overactive bladder and do not significantly increase with bladder distention. Neurourol Urodyn 28(1), 78–81. doi: 10.1002/nau.20599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe EM, Anand P, Terenghi G, Williams-Chestnut RE, Sinicropi DV, and Osborne JL (1997). Increased nerve growth factor levels in the urinary bladder of women with idiopathic sensory urgency and interstitial cystitis. Br J Urol 79(4), 572–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz EM, Sheward WJ, West KM, Morrow JA, Fink G, and Harmar AJ (1993). The VIP2 receptor: molecular characterisation of a cDNA encoding a novel receptor for vasoactive intestinal peptide. FEBS Lett 334(1), 3–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggi CA, Lecci A, Santicioli P, Del Bianco E, and Giuliani S (1992). Cyclophosphamide cystitis in rats: involvement of capsaicin-sensitive primary afferents. J Auton Nerv Syst 38(3), 201–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May V, Beaudet MM, Parsons RL, Hardwick JC, Gauthier EA, Durda JP, et al. (1998). Mechanisms of pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide (PACAP)-induced depolarization of sympathetic superior cervical ganglion (SCG) neurons. Ann N Y Acad Sci 865, 164–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May V, and Braas KM (1995). Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) regulation of sympathetic neuron neuropeptide Y and catecholamine expression. J Neurochem 65(3), 978–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May V, and Parsons RL (2017). G Protein-Coupled Receptor Endosomal Signaling and Regulation of Neuronal Excitability and Stress Responses: Signaling Options and Lessons From the PAC1 Receptor. J Cell Physiol 232(4), 698–706. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May V, and Vizzard MA (2010). Bladder dysfunction and altered somatic sensitivity in PACAP−/− mice. J Urol 183(2), 772–779. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.09.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill L, Gonzalez EJ, Girard BM, and Vizzard MA (2016). Receptors, channels, and signalling in the urothelial sensory system in the bladder. Nat Rev Urol 13(4), 193–204. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2016.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missig G, Mei L, Vizzard MA, Braas KM, Waschek JA, Ressler KJ, et al. (2017). Parabrachial Pituitary Adenylate Cyclase-Activating Polypeptide Activation of Amygdala Endosomal Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase Signaling Regulates the Emotional Component of Pain. Biol Psychiatry 81(8), 671–682. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missig G, Roman CW, Vizzard MA, Braas KM, Hammack SE, and May V (2014).Parabrachial nucleus (PBn) pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide (PACAP) signaling in the amygdala: implication for the sensory and behavioral effects of pain. Neuropharmacology 86, 38–48. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizumura K, and Murase S (2015). Role of nerve growth factor in pain. Handb Exp Pharmacol 227, 57–77. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-46450-2_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moller K, Reimer M, Hannibal J, Fahrenkrug J, Sundler F, and Kanje M (1997). Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating peptide (PACAP) and PACAP type 1 receptor expression in regenerating adult mouse and rat superior cervical ganglia in vitro. Brain Res 775(1–2), 156–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullins C, Bavendam T, Kirkali Z, and Kusek JW (2015). Novel research approaches for interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome: thinking beyond the bladder. Transl Androl Urol 4(5), 524–533. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2223-4683.2015.08.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazif O, Teichman JM, and Gebhart GF (2007). Neural upregulation in interstitial cystitis. Urology 69(4 Suppl), 24–33. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.08.1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogi K, Kimura C, Onda H, Arimura A, and Fujino M (1990). Molecular cloning and characterization of cDNA for the precursor of rat pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide (PACAP). Biochem Biophys Res Commun 173(3), 1271–1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkubo S, Kimura C, Ogi K, Okazaki K, Hosoya M, Onda H, et al. (1992). Primary structure and characterization of the precursor to human pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide. DNA Cell Biol 11(1), 21–30. doi: 10.1089/dna.1992.11.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okazaki K, Itoh Y, Ogi K, Ohkubo S, and Onda H (1995). Characterization of murine PACAP mRNA. Peptides 16(7), 1295–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okragly AJ, Niles AL, Saban R, Schmidt D, Hoffman RL, Warner TF, et al. (1999). Elevated tryptase, nerve growth factor, neurotrophin-3 and glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor levels in the urine of interstitial cystitis and bladder cancer patients. J Urol 161(2), 438–441; discussion 441–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto C, Martin M, Wolfer DP, Lipp HP, Maldonado R, and Schutz G (2001). Altered emotional behavior in PACAP-type-I-receptor-deficient mice. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 92(1–2), 78–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons CL (2007). The role of the urinary epithelium in the pathogenesis of interstitial cystitis/prostatitis/urethritis. Urology 69(4 Suppl), 9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.03.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson S, Schmelz M, McGlone F, Turner G, and Rukwied R (2009). Facilitated neurotrophin release in sensitized human skin. Eur J Pain 13(4), 399–405. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patnaik SS, Lagana AS, Vitale SG, Buttice S, Noventa M, Gizzo S, et al. (2017). Etiology, pathophysiology and biomarkers of interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome. Arch Gynecol Obstet 295(6), 1341–1359. doi: 10.1007/s00404-017-4364-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persu C, Cauni V, Gutue S, Blaj I, Jinga V, and Geavlete P (2010). From interstitial cystitis to chronic pelvic pain. J Med Life 3(2), 167–174. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pezet S, and McMahon SB (2006). Neurotrophins: mediators and modulators of pain. Annu Rev Neurosci 29, 507–538. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.112929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohlack ST, Nees F, Ruttorf M, Cacciaglia R, Winkelmann T, Schad LR, et al. (2015). Neural Mechanism of a Sex-Specific Risk Variant for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in the Type I Receptor of the Pituitary Adenylate Cyclase Activating Polypeptide. Biol Psychiatry 78(12), 840–847. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao LY, and Vizzard MA (2002). Cystitis-induced upregulation of tyrosine kinase (TrkA, TrkB) receptor expression and phosphorylation in rat micturition pathways. J Comp Neurol 454(2), 200–211. doi: 10.1002/cne.10447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao LY, and Vizzard MA (2004). Up-regulation of phosphorylated CREB but not c-Jun in bladder afferent neurons in dorsal root ganglia after cystitis. J Comp Neurol 469(2), 262– 274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ressler KJ, Mercer KB, Bradley B, Jovanovic T, Mahan A, Kerley K, et al. (2011). Post- traumatic stress disorder is associated with PACAP and the PAC1 receptor. Nature 470(7335), 492–497. doi: 10.1038/nature09856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter AM, Lewin GR, Kremer NE, and Mendell LM (1991). Requirement for nerve growth factor in the development of myelinated nociceptors in vivo. Nature 350(6318), 500– 502. doi: 10.1038/350500a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sant GR, and Hanno PM (2001). Interstitial cystitis: current issues and controversies in diagnosis. Urology 57(6 Suppl 1), 82–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sant GR, Kempuraj D, Marchand JE, and Theoharides TC (2007). The mast cell in interstitial cystitis: role in pathophysiology and pathogenesis. Urology 69(4 Suppl), 34– 40. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.08.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarchielli P, Mancini ML, Floridi A, Coppola F, Rossi C, Nardi K, et al. (2007). Increased levels of neurotrophins are not specific for chronic migraine: evidence from primary fibromyalgia syndrome. J Pain 8(9), 737–745. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnegelsberg B, Sun TT, Cain G, Bhattacharya A, Nunn PA, Ford AP, et al. (2010). Overexpression of NGF in mouse urothelium leads to neuronal hyperinnervation, pelvic sensitivity, and changes in urinary bladder function. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 298(3), R534–547. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00367.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spengler D, Waeber C, Pantaloni C, Holsboer F, Bockaert J, Seeburg PH, et al. (1993). Differential signal transduction by five splice variants of the PACAP receptor. Nature 365(6442), 170–175. doi: 10.1038/365170a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroth N, and Eiden LE (2010). Stress hormone synthesis in mouse hypothalamus and adrenal gland triggered by restraint is dependent on pituitary adenylate cyclase- activating polypeptide signaling. Neuroscience 165(4), 1025–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studeny S, Cheppudira BP, Meyers S, Balestreire EM, Apodaca G, Birder LA, et al. (2008). Urinary bladder function and somatic sensitivity in vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP)−/− mice. J Mol Neurosci 36(1–3), 175–187. doi: 10.1007/s12031-008-9100-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theoharides TC, Sant GR, el-Mansoury M, Letourneau R, Ucci AA Jr., and Meares EM Jr. (1995). Activation of bladder mast cells in interstitial cystitis: a light and electron microscopic study. J Urol 153(3 Pt 1), 629–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukiyama N, Saida Y, Kakuda M, Shintani N, Hayata A, Morita Y, et al. (2011). PACAP centrally mediates emotional stress-induced corticosterone responses in mice. Stress 14(4), 368–375. doi: 10.3109/10253890.2010.544345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaudry D, Falluel-Morel A, Bourgault S, Basille M, Burel D, Wurtz O, et al. (2009). Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide and its receptors: 20 years after the discovery. Pharmacol Rev 61(3), 283–357. doi: 10.1124/pr.109.001370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vizzard MA (2000a). Changes in urinary bladder neurotrophic factor mRNA and NGF protein following urinary bladder dysfunction. Exp Neurol 161(1), 273–284. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vizzard MA (2000b). Up-regulation of pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide in urinary bladder pathways after chronic cystitis. J Comp Neurol 420(3), 335–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vizzard MA (2000c). Up-regulation of pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide in urinary bladder pathways after chronic cystitis. J Comp Neurol 420(3), 335–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vizzard MA (2001a). Alterations in neuropeptide expression in lumbosacral bladder pathways following chronic cystitis. J Chem Neuroanat 21(2), 125–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vizzard MA (2001b). Alterations in neuropeptide expression in lumbosacral bladder pathways following chronic cystitis. J Chem Neuroanat 21(2), 125–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vizzard MA, Erdman SL, Forstermann U, and de Groat WC (1994). Ontogeny of nitric oxide synthase in the lumbosacral spinal cord of the neonatal rat. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 81(2), 201–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf CJ, Allchorne A, Safieh-Garabedian B, and Poole S (1997). Cytokines, nerve growth factor and inflammatory hyperalgesia: the contribution of tumour necrosis factor alpha. Br J Pharmacol 121(3), 417–424. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura N, Bennett NE, Hayashi Y, Ogawa T, Nishizawa O, Chancellor MB, et al. (2006). Bladder overactivity and hyperexcitability of bladder afferent neurons after intrathecal delivery of nerve growth factor in rats. J Neurosci 26(42), 10847–10855. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3023-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura N, and de Groat WC (1999). Increased excitability of afferent neurons innervating rat urinary bladder after chronic bladder inflammation. J Neurosci 19(11), 4644–4653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y, and de Groat WC (2008). Sensitization of pelvic afferent nerves in the in vitro rat urinary bladder-pelvic nerve preparation by purinergic agonists and cyclophosphamide pretreatment. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 294(5), F1146–1156. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00592.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Shi TJ, Ji RR, Zhang YZ, Sundler F, Hannibal J, et al. (1995). Expression of pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide in dorsal root ganglia following axotomy: time course and coexistence. Brain Res 705(1–2), 149–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YZ, Hannibal J, Zhao Q, Moller K, Danielsen N, Fahrenkrug J, et al. (1996). Pituitary adenylate cyclase activating peptide expression in the rat dorsal root ganglia: up-regulation after peripheral nerve injury. Neuroscience 74(4), 1099–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvara P, and Vizzard MA (2007). Exogenous overexpression of nerve growth factor in the urinary bladder produces bladder overactivity and altered micturition circuitry in the lumbosacral spinal cord. BMC Physiol 7, 9. doi: 10.1186/1472-6793-7-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]