Abstract

The AB5 toxins cholera toxin (CT) from Vibrio cholerae and heat-labile enterotoxin (LT) from enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli are notorious for their roles in diarrheal disease, but their effect on other intestinal bacteria remains unexplored. Another foodborne pathogen, Campylobacter jejuni, can mimic the GM1 ganglioside receptor of CT and LT. Here we demonstrate that the toxin B-subunits (CTB and LTB) inhibit C. jejuni growth by binding to GM1-mimicking lipooligosaccharides and increasing permeability of the cell membrane. Furthermore, incubation of CTB or LTB with a C. jejuni isolate capable of altering its lipooligosaccharide structure selects for variants lacking the GM1 mimic. Examining the chicken GI tract with immunofluorescence microscopy demonstrates that GM1 reactive structures are abundant on epithelial cells and commensal bacteria, further emphasizing the relevance of this mimicry. Exposure of chickens to CTB or LTB causes shifts in the gut microbial composition, providing evidence for new toxin functions in bacterial gut competition.

Bacterial AB5 toxins, such as cholera toxin, bind to oligosaccharides on the host cell surface and play key roles in the pathogenesis of diarrheal disease. Here, Patry et al. show that these toxins bind also to bacterial oligosaccharides and inhibit the growth of Campylobacter jejuni and gut commensal bacteria.

Introduction

The gut microbiome is an exceedingly complex ecosystem where bacteria employ every tactic at their disposal to gain an advantage over competitors while avoiding clearance by the host. Among these strategies, bacteria display a diverse array of surface glycan structures1 and mimic host glycans2–5 to evade immune recognition. Given that these structures are prominently exposed, many animals have developed innate glycan-binding proteins, such as toll-like receptors or siglecs6, to target non-self pathogen-associated molecular patterns and aid in immune clearance. There are also several glycan binding proteins such as galectins7, intelectins8 and resistin-like molecule β (RELMβ)9 that directly inhibit bacterial spread in the intestine. This study explores the ability of bacteria to use glycan binding proteins to target each other, contributing to competition between groups within the intestinal ecosystem.

Cholera toxin (CT) is produced by Vibrio cholerae, the causative agent of cholera, a devastating gastrointestinal disease currently endemic in 51 countries10. The toxin is a member of the AB5 group of bacterial toxins and consists of 5 B-subunits that specifically target cell surface glycan receptors and trigger entry into the host11. AB5 toxins also contain an enzymatic A-subunit responsible for the toxic effect observed. The A-subunit of CT ADP-ribosylates the Gsα protein of adenylate cyclase, causing it to bind GTP and constitutively stimulate conversion of ATP to cyclic AMP (cAMP)12. This leads to increased efflux of ions into the intestinal lumen, resulting in the rice-water diarrhea and severe dehydration that are hallmarks of the disease13. The B-subunits of CT (CTB) are arranged in a symmetrical, ring-shaped pentamer14,15. It was originally believed that CTB bound to GM1 gangliosides on the apical surface of intestinal epithelial cells to achieve entry16. This hypothesis predominated in part due to CT’s exceptionally high affinity for its receptor, with a reported dissociation constant of 0.73 nM17. However, the dogma that binding to the intestinal epithelium is mediated through GM1 gangliosides has recently been disputed due to observations that these receptors are sparsely present in the human GI tract18,19. Further reports demonstrate that CT is capable of binding to fucosylated structures that serve as functional receptors for the toxin19–21.

Heat-labile enterotoxin (LT) from enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) is another AB5 toxin that shares a similar structure and function to CT. Both exhibit nM affinities for GM1 ganglioside receptors, though recent studies have identified other, albeit lower-affinity, receptors for these toxins. LT is capable of binding to blood group antigens, and both CT and LT were shown to bind several human milk oligosaccharides, notably those containing fucosylated residues20. It has been shown that the fucose binding sites on these toxins are distinct from those binding GM1 gangliosides20, leading us to question the role of the high affinity GM1 binding sites on these toxins. Notably, CT has been used as a reagent to assess GM1 ganglioside mimicry of another gastrointestinal pathogen, Campylobacter jejuni22.

C. jejuni is a leading cause of gastroenteritis worldwide23,24. In addition, C. jejuni can cause the serious post-infectious sequelae Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS) through its ability to mimic human gangliosides with the lipooligosaccharide (LOS) structures displayed on its surface25. Gangliosides are glycolipids containing sialic acid in their carbohydrate structure and are attached to ceramide lipids. These structures commonly decorate nerve cells but can also be found on other cells throughout the body. LOS is a shorter lipopolysaccharide (LPS) lacking the O-antigen and consists of a lipid A portion, which anchors it to the cell wall, as well as inner and outer core oligosaccharides. Among C. jejuni strains, the outer core structure exhibits considerable variation in the type and arrangement of the saccharides presented. Many C. jejuni strains sialylate their LOS, enabling them to mimic human gangliosides25.

Approximately 60% of C. jejuni strains can mimic gangliosides26, including GM1, GM2, GM3, GD1a, GD1b, GD2, GD3, and GT1a ganglioside types27. This subset encompasses most of the major gangliosides found in the human body, and mimicry of these structures is believed to allow C. jejuni to escape immune detection by their hosts. GBS occurs when there is a breakdown in immune tolerance and the host generates α-ganglioside antibodies that not only attack the pathogen but subsequently recognize host nerve cells as foreign. This leads to degradation of spinal nerve axons and paralysis28. GM1 gangliosides are the most common gangliosides mimicked by C. jejuni glycans (structures depicted in Fig. 1), and CT has been used to probe for the expression of these structures on its surface22.

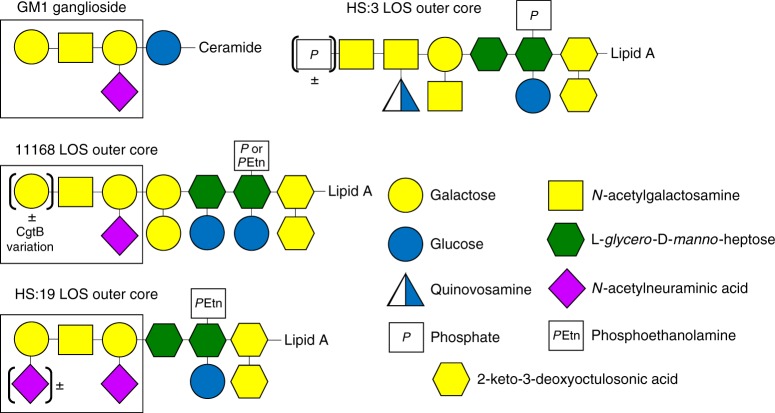

Fig. 1.

Structures of GM1 ganglioside and the outer LOS core of the wildtype C. jejuni strains used in this study. The portion of each receptor that is recognized by α-GM1 antibodies and cholera toxin is indicated by the box

The ability of CTB to bind C. jejuni is strain-dependent, due to variation in LOS structures resulting from differences in biosynthetic enzymes and/or variation in the expression of terminal sugar transferases27. The heat-stable (HS) serostrain HS:19, along with its serogroup members, have most commonly been isolated from GBS patients and express a heterogeneous LOS outer core displaying a mixture of GM1 and GD1a mimics29. Conversely, the HS:3 serostrain is incapable of mimicking gangliosides since the strain lacks enzymes to synthesize the appropriate sugars26. The 11168 strain of C. jejuni is capable of phase-varying its cgtB gene (cj1139c), which encodes the β 1–3 galactosyltransferase responsible for addition of a terminal galactose onto the LOS22. This strain can vary its GM1 ganglioside mimics through slipped-strand mispairing in the poly-guanosine tract within cgtB (Fig. 1) resulting in premature truncation of the transferase and loss of mimicry22.

In this study, we demonstrate that CTB and LT increase cell membrane permeability and inhibit the growth of GM1-mimicking C. jejuni strains, presenting novel functions for these toxins. This effect is observed void of the toxic A subunit of each toxin and selects for C. jejuni variants not expressing GM1 mimicry. In addition, we identify another CT-binding bacterium in the chicken gut, Enterococcus gallinarum/casseliflavus, and provide evidence that oral administration of CTB and LT B-subunit (LTB) to chickens induces changes in the gut microbiome.

Results

Cholera toxin shows GM1-dependent binding to C. jejuni

A schematic of the LOS outer core structures of each strain used in this study is depicted in Fig. 1, along with GM1 ganglioside for comparison. CTB binding to C. jejuni LOS was compared by transmission electron microscopy and immunogold labeling (Fig. 2a–c). CTB binding was dependent on the presence of LOS-mimicking GM1 structures. C. jejuni HS:19 cells, which express GM1 mimics29, showed toxin binding (Fig. 2a), whereas C. jejuni HS:3 cells unable to mimic GM1, showed no toxin binding (Fig. 2c). C. jejuni 11168, which is known to display a mixed population of LOS variants22, showed a mixed CTB binding phenotype (Fig. 2b).

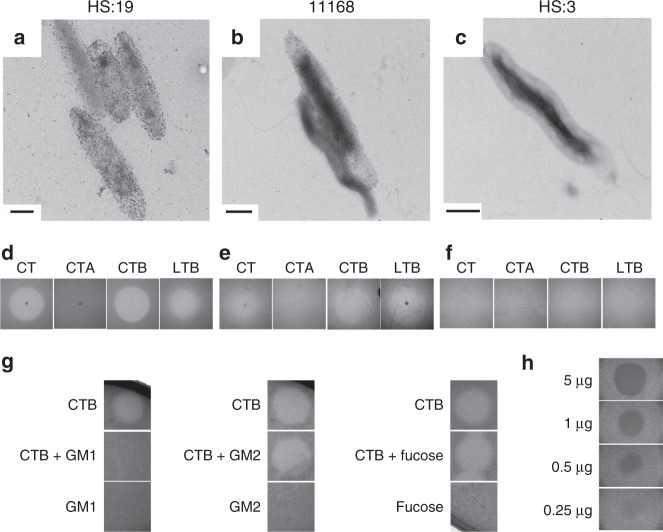

Fig. 2.

Cholera toxin B subunit (CTB) and heat-labile enterotoxin B subunit (LTB) bind and clear GM1 ganglioside-mimicking C. jejuni strains. a–f Transmission electron micrographs depicting different C. jejuni strains bound by immunogold-labeled CTB (a–c, scale bars are 0.5 μm), accompanied by images of agar plates showing C. jejuni following exposure to 2 μL of either CT, CTB, CTA, or LTB (each at 1 mg mL-1) for 24 h while growing in soft agar (d–f). a, d C. jejuni HS:19. b, e C. jejuni 11168. C, F) C. jejuni HS:3. g Competitive clearance assay where CTB was mixed 1:1 with indicated glycans prior to spotting onto growing C. jejuni HS:19. h CTB spotted on C. jejuni HS:19 in various concentrations to determine the amount needed for clearance

The B-subunits of CT and LT clear C. jejuni growth

CT, CTA, CTB and LTB were spotted on agar plates containing different C. jejuni strains to determine the effect of toxin binding on the growth of each strain. A zone of clearance was observed when CT, CTB, or LTB were spotted on C. jejuni HS:19 (Fig. 2d). This phenotype was not observed for strain HS:3, which does not bind CT (Fig. 2f), while the partial clearance observed for strain 11168 reflects the mixed binding phenotype (Fig. 2e). The clearance caused by CTB suggests that the enzymatically active A-subunit known to be toxic to eukaryotic cells was not necessary to cause the clearance phenotype. LTB, the B-subunit of the related AB5 toxin also showed similar clearance to that seen with CTB (Fig. 2). When these same treatments were applied to E. coli CWG308 pGM1a/pCst, a strain engineered to display the GM1 ganglioside mimic on its LOS, no clearance was observed (Supplementary Fig. 1).

To confirm that the observed clearance was mediated through the GM1 ganglioside-binding domain of the toxin and not through the fucose-binding domain, CTB was mixed at a 1:1 ratio with GM1 ganglioside, GM2 ganglioside or fucose prior to spotting onto C. jejuni HS:19-containing plates (Fig. 2g). The GM1 ganglioside competitively inhibited the clearance effect of CTB, while neither pre-incubation with GM2 or with fucose had an effect, indicating that the GM1 ganglioside-binding domain of the toxin is required for the clearing activity. The minimum amount of toxin required to see this effect was determined to be 0.25 μg (4.3 μM) by spotting various concentrations of CTB onto C. jejuni HS:19 and observing the extent of clearance in each zone (Fig. 2h).

CTB mediated clearance is bacteriostatic

To better understand the clearance phenotype, scanning electron microscopy was used to examine the interface between the clearance/growth zone on C. jejuni HS:19 plates. Squares of agar were excised from either inside, outside, or directly on the edge of the clearance zones, to visualize the growth simultaneously (Fig. 3a). When viewed at low magnification, regions outside of the CTB clearance zone showed growth in many discrete spheres, whereas these spheres were more sparsely distributed within the clearance zone (Fig. 3b). This difference was also apparent at higher magnifications, where a drastic decrease in the number of C. jejuni cells inside the clearance zone was observed compared to outside (Fig. 3c vs. 3e), but all showed normal cell morphologies (Fig. 3d, f, Supplementary Fig. 2A and 2B). Addition of CTB to agar plates with already existing C. jejuni growth did not cause clearing (Supplementary Fig. 2D). These results support the hypothesis that toxin exposure leads to decreased C. jejuni growth in the observed zones of clearance.

Fig. 3.

Scanning electron micrographs depicting C. jejuni HS:19 grown in NZCYM soft agar following exposure to cholera toxin B subunit (CTB). a Clearance zone 24 h after spotting CTB (the white square indicates the location of the excised agar slab). b A low magnification image highlighting the difference in surface structure of the agar slab between the exposed area (left side) and the unexposed area (right side). c, d Increasingly magnified images of the agar surface inside the zone of clearance. e, f Increasingly magnified images of the agar surface outside the zone of clearance. Images are representative of 3 replicate experiments

Changes in LOS and cgtB suggest selection against mimic

To analyze whether cells exposed to CTB and LTB can alter their LOS structures and phase-vary GM1 ganglioside mimics, the LOS was isolated from C. jejuni 11168 cells inside and outside CTB and LTB clearance zones. LOS from each was compared using SDS-PAGE followed by silver staining to visualize molecular weight differences in the LOS (Fig. 4a), and then by far western blotting with CTB to verify decreased LOS recognition by CTB (Fig. 4b). The silver stained LOS from cells isolated from outside the zones showed a doublet (indicated by the arrow) and was reduced to a single lower molecular weight band for LOS isolated from cells inside the clearance zones (Fig. 4a). The top band of the doublet (Fig. 4a, lane 1) was presumed to represent the full length LOS and the lower band to be lacking the terminal galactose residue. The LOS single band from cells inside the zones migrates similar to the lower of the two bands of the doublet from outside the clearance zone. To confirm this, a far western blot probed with CTB was done on the same samples and showed much greater CTB binding to LOS isolated from cells unexposed to CTB/LTB compared with those that had already been exposed (Fig. 4b). The shift in mass and reduction in CTB binding observed in CTB/LTB-exposed cells suggests that exposure to the toxin provides a selective pressure against GM1 ganglioside mimicry in C. jejuni.

Fig. 4.

Exposure of C. jejuni 11168 cells to cholera toxin B subunit (CTB) led to changes in lipooligosaccharide (LOS) structure. This is shown by silver stain (a) and far western blot using CTB as a probe (b). CTB exposure also led to changes in the length of the poly-G tract in the cgtB gene, which is essential for GM1 ganglioside mimicry, leading to a frameshift mutation (c). The arrow in a marks the two bands associated with two distinct LOS structures in wildtype 11168 and the arrow in c marks the ninth G in the homopolymeric tract where heterogeneity is seen in the sequence. Source data are provided as a Source Data file

To determine whether sequence variation in cgtB (necessary for addition of the terminal galactose in generating the GM1 mimic) led to the alteration in C. jejuni LOS following CTB or LTB exposure, DNA was isolated from C. jejuni 11168 cells inside and outside the same clearance zones. The cgtB gene was then PCR-amplified and sequenced from each sample. Interestingly, cells outside the zone of clearance displayed sequence heterogeneity at the homopolymeric G tract in cgtB, indicative of a population comprised of cells containing either 8 or 9 Gs in this region (Fig. 4c). However, this heterogeneity was not present for cells obtained inside the zones of clearance, which consistently showed a sequence of 9 Gs. This shift from 8 to 9 Gs causes a frameshift during cgtB mRNA translation, which creates a premature stop codon resulting in a non-functional protein and abrogation of GM1 ganglioside mimicry22. It is apparent from our data that C. jejuni 11168 cells inside CTB- and LTB-induced zones of clearance have “switched off” expression of cgtB, supporting the hypothesis that exposure to CTB or LTB constitutes a selective pressure against GM1 mimic expression.

Exposure to CTB increases cell permeability to EtBr

To determine if the inhibitory effect of CTB binding was due to a change in membrane permeability, accumulation of ethidium bromide (EtBr) inside the cells was measured by spectrophotometry. EtBr has been used previously to measure cell membrane permeability changes, as well as activity of multi-drug efflux pumps30,31. C. jejuni 11168 was used for this experiment along with several isogenic mutants (Table 1) including two abolishing GM1 mimicry (cgtB and neuC1) and one in the major efflux pump gene, cmeA. As seen in Fig. 4, addition of CTB to the C. jejuni wildtype, capable of mimicking GM1 gangliosides, resulted in an increased influx of EtBr unrelated to C. jejuni efflux pump activity. The relative fluorescence recorded 20 min after EtBr addition changed significantly when 11168 wildtype cells had been exposed to CTB (n = 21, dF = 40, t = 4.3294, p = 9.74 × 10−5, t-test) and as well for ΔcmeA (n = 12, dF = 22, t = 2.4580, p = 0.0223, t-test); however no difference was observed when the toxin could no longer bind in ΔcgtB (n = 12, dF = 22, t = 0.9388, p = 0.3580, t-test) and ΔneuC1 (n = 12, dF = 22, t = 1.4302, p = 0.1667, t-test). Consistent with the spot assay, we did not see a change in EtBr uptake following CTB treatment of E. coli CWG308 pGM1a/pCst (n = 6, dF = 10, t = 1.8869, p = 0.0885, t-test) (Supplementary Fig. 1D). E. coli CWG308 wildtype showed a statistically significant increase in fluorescence after CTB exposure (n = 9, dF = 16, t = 3.8268, p = 0.0015, t-test), but this difference was small in comparison to that seen for C. jejuni 11168 and the significance may result more from low data variance (Supplementary Fig. 1D). Relative fluorescence measurements were taken every 2 min, but the trends remained relatively consistent throughout (Supplementary Fig. 3). These findings support that CTB causes an increase in membrane permeability upon binding to C. jejuni and is correlated with strains that show the clearance phenotype.

Table 1.

Strains and mutants used in this study

| Strain or mutant | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|

| C. jejuni HS:19 serostrain | Human clinical isolate displaying both GM1 and GD1a ganglioside mimics. | ATCC 4344667 |

| C. jejuni HS:3 serostrain | Isolate incapable of mimicking mammalian gangliosides due to lack of sialic acid biosynthesis genes. | ATCC 4343167 |

| C. jejuni 11168 | Human clinical isolate displaying GM1 and GM2 gangliosides dependent on the phase-variable state of the cgtB gene. | 68 |

| C. jejuni 11168 ΔcgtB::kanR | Kanamycin cassette knockout mutant in the cgtB gene incapable of adding terminal galactose to generate GM1 ganglioside mimic. | This study |

| C. jejuni 11168 ΔcmeA::cmR | Chloramphenicol cassette knockout mutant in the cmeA gene creating a non-functional multi-drug efflux pump. | This study |

| C. jejuni 11168 ΔneuC1::kanR | Kanamycin cassette knockout mutant in the neuC1 gene incapable of creating N-acetylneuraminic acid to generate GM1 ganglioside mimic. | This study |

| E.coli CWG308 | waaO mutant of E. coli R1 strain F470 with truncated LPS containing only the lipid A and inner core portions. | 69 |

| E.coli CWG308 pGM1a/pCst | A mutant made in E. coli CWG308 which harbors C. jejuni cgtA, cgtB and cstII, as well as Neisseria lgtE and E. coli gne on two separate plasmids, to display LOS GM1 ganglioside mimics. | 70 |

| Enterococcus gallinarum/casseliflavus | A GM1 ganglioside-mimicking bacterium isolated from the chicken cecum. | This study |

CTB reduces C. jejuni virulence in Galleria mellonella model

The G. mellonella model is commonly used to assess C. jejuni virulence due to its susceptibility to C. jejuni infection and mortality phenotype in response to virulent strains32. To test the potential impact of CTB on C. jejuni pathogenicity, ~ 1.0 × 109 colony forming units of C. jejuni HS:19 was introduced into the hind-leg of G. melonella to assess its virulence in the presence of CTB. When C. jejuni was incubated with CTB prior to injection, a significant increase (n = 9, dF = 16, t = 4.3374, p = 0.0005, t-test) in larvae survival was observed after 5 days infection compared to HS:19 administered alone (Fig. 5). This indicates that CTB binding to C. jejuni has a significant impact on its ability to infect and cause disease in a model host.

Fig. 5.

Cholera toxin B subunit (CTB) increases membrane permeability and reduces C. jejuni virulence in the Galleria mellonella model. a C. jejuni 11168 wildtype (n = 21 per condition), ΔcgtB (n = 12 per condition), ΔcmeA (n = 12 per condition) and ΔneuC1 (n = 12 per condition) were incubated with ethidium bromide for 20 min following treatment with PBS (white) or CTB (gray) and the relative fluorescence when exposed to CTB was measured. b G. mellonella larvae were inoculated with C. jejuni HS:19 alone (n = 9) or together with CTB (n = 9), MgSO4 buffer alone (n = 6), or MgSO4 buffer together with CTB (n = 3), and larvae survival rates were determined after 5 days. Error bars represent the standard error within each group. ***p-value ≤ 0.001, *p-value ≤ 0.05 determined by two-tailed t-test. Source data are provided as a Source Data file

CTB binds to mucins, epithelium and commensal bacteria

Chickens are a common host for C. jejuni so cloacal swabs were performed on 10% of chickens upon arrival to confirm that we received a Campylobacter-negative flock by plating onto Karmali selective agar. At the termination of the experiment, cecal contents from all birds were serially diluted and plated onto Karmali agar to confirm the chickens were not colonized with C. jejuni. To determine whether chicken intestinal epithelial cells or chicken gut bacteria other than C. jejuni display GM1 mimics or fucosylated structures capable of CTB binding, chicken ceca and their contents were fixed, and cross-sections were paraffin-embedded and sectioned for analysis by immunofluorescent microscopy. Paraffin cross-sections were probed using either CTB or α-GM1 ganglioside antibodies. CTB bound strongly to the apical surface of the epithelium, to the mucus layer and to mucin-filled goblet cells (Fig. 6a, c). A majority of the binding to mucus was negated by prior treatment of the slides with α1-2-fucosidase (Fig. 6d), suggesting that this binding was mediated by the fucose binding site of CTB. CTB also bound to commensal bacteria present within the cecal lumen (Fig. 6e). Similar to CTB, α-GM1 ganglioside antibodies labeled both the apical border of the epithelium, as well as many commensal bacteria within the cecal lumen (Fig. 6b, f). However, unlike CTB, the α-GM1 ganglioside antibody did not bind the mucus or goblet cells (Fig. 6a, b). This indicates that CTB may bind to the apical epithelium and to bacteria colonizing the chicken intestine via its GM1-binding site, since it shares specificity for these structures with αGM1 antibodies. In addition, our evidence suggests that CTB binds mucus and goblet cells via its fucose receptor, as binding to these components was abrogated by fucosidase treatment and since specificity for these components is not shared with α-GM1 antibodies.

Fig. 6.

Cholera toxin (CT) binds to goblet cells, mucins and commensal bacteria in the chicken cecum. Fluorescence microscopy of sequentially cut chicken cecal cross-sections labeled with DAPI (blue) and either α-CT (green) (a, c–e, g) or α-GM1 ganglioside (green) (b, f, h). Images a–d were taken at ×200. Arrows in a, b indicate goblet cells and mucus. d Cells were treated with fucosidase prior to labeling. e, f Magnified images to show bacterial binding. g CTB (green) and DAPI (blue) labeling of bacteria isolated after CTB-protein G pulldown of bacteria isolated from the initial GM1-protein G pull-down h Bacteria isolated after GM1 pulldown and labeled with DAPI (blue) and α-GM1 (green)

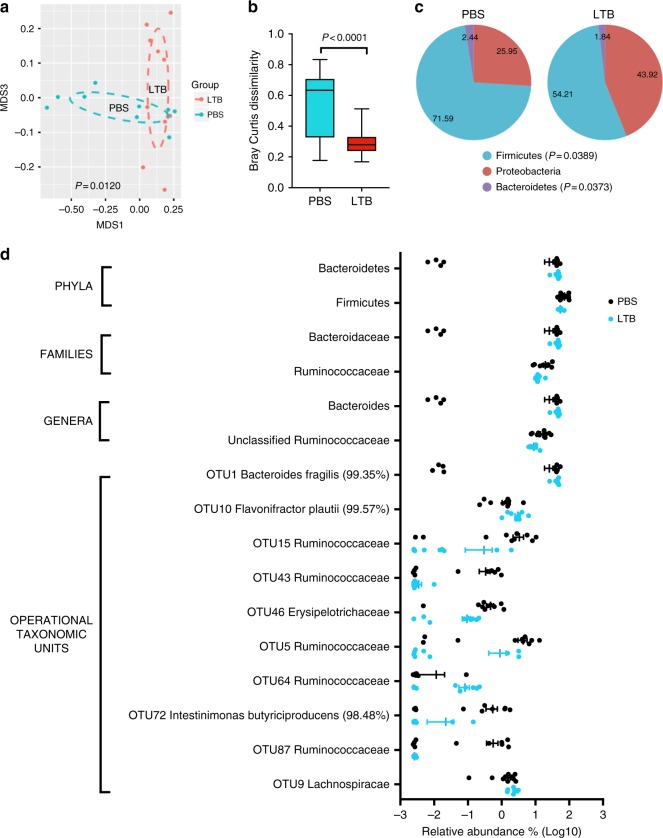

LTB administration to chickens shifts intestinal microbiota

Given the evidence that AB5 toxins bind to a subset of bacteria present in the chicken intestine, we next examined if such toxins impact the composition of the chicken intestinal microbiota. We compared the 16S rRNA gene sequence profile of the cecal bacterial communities in chickens treated with LTB (n = 9) or with PBS (n = 10) as a control (dF = 17). We focused this experiment on LTB since enterotoxin producing E. coli strains have been reported in chickens33,34, and producing these toxins may be ecologically relevant. Administration of LTB causes shifts in the overall composition of the gut microbiome relative to PBS-treated chickens as shown by NMDS analysis of Bray Curtis dissimilarity (p = 0.0120 by Adonis PERMANOVA test) (Fig. 7a). Although α-diversity is not affected, LTB significantly reduces β-diversity of the cecal bacterial community (Fig. 7b), indicating that the toxin lowers inter-individuality of the gut microbiota. In terms of specific taxa, we found that LTB caused major shifts in the abundance of bacteria classified within the phyla Firmicutes (p = 0.04) and Bacteroidetes (p = 0.04) (Fig. 7c, Table 2, statistical significance determined by two-tailed unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction). Analysis of relative abundance at lower taxonomic levels shows that the majority of changes involve decreases in the families Ruminococcaceae (p = 0.02) and Lachnospiraceae (p = 0.05), as well as genera and OTUs within these families, while the genus Bacteroides was increased (p = 0.04) (Fig. 7d, Table 2). These findings demonstrate that LTB has a major effect on the chicken gut microbiota.

Table 2.

Relative abundance and p-values of statistically significant changes in taxa caused by administration of LTB

| Taxonomic level | Name | PBS (%) | LTB (%) | p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phylum | Bacteroidetes | 25.9458 | 43.9206 | 0.0373 |

| Phylum | Firmicutes | 71.5893 | 54.2123 | 0.0389 |

| Family | Bacteroidaceae | 25.9458 | 43.9206 | 0.0373 |

| Family | Lachnospiraceae | 42.8754 | 31.8613 | 0.0507 |

| Family | Ruminococcaceae | 19.529 | 12.2352 | 0.0197 |

| Genus | Bacteroides | 25.9458 | 43.9206 | 0.0373 |

| Genus | unclassified_Ruminococcaceae | 16.4285 | 8.9802 | 0.0096 |

| OTU1 | Bacteroides fragilis (99.35%) | 25.7470 | 42.5499 | 0.0478 |

| OTU10 | Flavonifractor plautii (99.57%) | 1.4066 | 3.0087 | 0.0214 |

| OTU15 | Ruminococcaceae | 3.3204 | 0.3017 | 0.0247 |

| OTU43 | Ruminococcaceae | 0.3348 | 0.0034 | 0.0168 |

| OTU46 | Erysipelotrichaceae | 0.4693 | 0.0941 | 0.0064 |

| OTU5 | Ruminococcaceae | 4.3303 | 0.8824 | 0.0302 |

| OTU64 | Ruminococcaceae | 0.0116 | 0.0822 | 0.0198 |

| OTU72 | Intestinimonas Butyriciproducens_(98.48%) | 0.5461 | 0.0219 | 0.0266 |

| OTU87 | Ruminococcaceae | 0.5623 | 0.0026 | 0.0214 |

| OTU9 | Lachnospiraceae | 1.5424 | 2.3670 | 0.0227 |

*Statistical significance obtained using two-tailed unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction

Fig. 7.

AB5 toxins cause shifts in the gut microbiome of chickens by affecting diversity and composition. a NMDS plot based on Bray Curtis distances show that introduction of heat-labile enterotoxin (LTB, n = 9) causes a significant shift (p = 0.0120, Adonis PERMANOVA test) in the gut microbiome of chickens relative to chickens treated with PBS (n = 10). b Although α-diversity is not affected, LTB decreases β-diversity (p < 0.0001, two-tailed unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction) indicating that the toxin lowers inter-individuality of the gut microbiota. c LTB decreases the relative abundance of Firmicutes (p = 0.0389) with parallel increases in Bacteroidetes (p = 0.0373). d Significant changes in relative abundance (expressed as log10) at selected taxonomic level (see Table 2 for p-values and percentages of relative abundance). Whiskers in b represent minimum and maximum values. Lines and bars in d represent means and standard error of means. Source data are provided as a Source Data file

To test if similar findings apply to CTB, we sequenced the gut microbiota of three birds receiving CTB and three with PBS. Although statistical significance could not be obtained, we observed similar trends to those obtained with LTB (Supplementary Fig. 4). Overall, our findings indicate that AB5 toxins affect more than just C. jejuni in the chicken gut.

Isolation and identification of GM1-mimicking Firmicutes

Upon finding evidence to support other GM1-ganglioside mimicking bacteria in the chicken gut impacted by AB5 toxins, α-GM1-protein G agarose was used to pull-down bacteria that display ganglioside mimics on their surface. Isolated bacteria were screened and one GM1-positive species, confirmed to bind α-GM1 and CTB by fluorescence microscopy, was further characterized. The isolate was identified as Enterococcus gallinarum/casseliflavus, a member of the Firmicutes phylum. Fluorescent microscopy of the isolated strain with α-GM1 ganglioside antibody showed two distinct populations with only a fraction of cells being bound by the GM1 antibody (Fig. 6g), Further pull-downs with CTB in combination with α-CTB and protein G agarose intended to isolate the GM1-ganglioside mimicking variants (Fig. 6h) followed by microscopic analyses after CTB-α-CTB surface staining resulted in a similar phenotype with only a fraction of bacteria being positive for CTB binding. This indicates that only a fraction of the culture expresses the potential GM1 mimics in vivo, reminiscent of potential phase-variation as observed in C. jejuni 11168.

Discussion

It has long been considered that the primary role of bacterial toxins is to target vertebrate hosts and cause disease35. Another assumption, that has recently been disputed, is that GM1 gangliosides in the human gut are necessary for CT to induce disease in humans19. However, since CT is capable of binding to C. jejuni GM1 ganglioside mimics22, and the toxin genes are encoded by a V. cholerae bacteriophage36, we thought it was possible for CT to possess an antibacterial function. C. jejuni is capable of mimicking various host gangliosides through variation of its LOS outer core, which allows the organisms to evade host immune detection37,38. Furthermore, C. jejuni is an intestinal pathogen that occupies a niche shared with other enteric pathogens such as V. cholerae, suggesting the two organisms could compete for resources37.

In endemic areas, C. jejuni is rarely the sole enteric pathogen infecting an individual, and the organism is routinely isolated from humans co-infected with V. cholerae and/or enterotoxigenic E. coli39,40. The latter produces LT, another AB5 toxin with binding and enzymatic properties remarkably similar to CT41. AB5 toxin-producing bacteria have also been found in chickens, a common commensal host for C. jejuni33,34,42–44. As a result, C. jejuni may come into contact with ganglioside-targeting, AB5 toxin-producing bacteria in its natural environment. This study has demonstrated that CT and LT do in fact inhibit growth of GM1-mimicking C. jejuni. In addition, we have shown that when fed to chickens, LTB (and CTB) alter the microbial composition of the chicken intestinal tract, suggesting that these toxins and others like it may indeed play a role in inter-bacterial warfare.

After confirming that CT binding to C. jejuni was dependent on GM1 ganglioside mimicry and that this binding inhibited C. jejuni growth, we tested which component of the AB5 toxins mediated the antibacterial activity. Interestingly, we found that the B-subunit was sufficient for the binding and growth clearance phenotype. This was unexpected, since the B-subunit of these toxins, while crucial for adhesion and internalization by eukaryotic cells, as well as for immune activation in humans and animals, is not toxic to eukaryotic tissues without the enzymatically active A-subunit45. In contrast, the antibacterial effect we observed appears to be mediated through binding by the toxin. It is important to note however, that we have not excluded the possibility that the A and B subunits could have a synergistic effect to cause increased clearance when the two are together in the holotoxin configuration.

The fact that the binding subunits of CTB and LTB alone are sufficient for clearance shows that the ADP-ribosylating action of the toxins is not necessary for the activity. The observations that this exposure does not alter individual cell morphology (Supplementary Fig. 2A-B) and that CTB does not clear C. jejuni if added after cells have grown (Supplementary Fig. 2) suggest that the observed effect is bacteriostatic as opposed to bactericidal. This is in contrast to lysis buffer, which causes visible clearing within minutes of spotting onto C. jejuni (Supplementary Fig. 2D). In Cryptococcus neoformans, growth inhibition has been observed as a result of antibodies directed against its capsular polysaccharide; the antibodies completely surround the cells and prevent it from dividing by encapsulating the organism46. However, if our observed CTB-induced clearing occurred via the same mechanism, we would expect α-GM1 antibodies to reproduce the clearing effect, which we did not observe (Supplementary Fig. 2). Since the outer leaflet of the outer membrane acts as a permeability barrier, helping bacteria to regulate flow of harmful compounds, as well as beneficial nutrients47, we postulated that disruption of this barrier may cause the bacteriostatic effect that we observe. Indeed, the results of our EtBr accumulation assay suggest that the mechanism is related to an increase in membrane permeability upon toxin binding. To determine if increased EtBr accumulation was an effect of the toxin blocking active efflux of EtBr, a mutant in the periplasmic component of the Campylobacter multidrug efflux pump, cmeA was inactivated. This mutant still showed an increase in EtBr permeability even in the absence of an active efflux pump, suggesting that CTB might act directly on the membrane. Interestingly, although CTB bound extensively to E. coli CWG 308 pGM1/pCst displaying GM1 ganglioside mimics on its LOS, none of the toxin subunits or the CT holotoxin were able to clear this engineered strain (Supplementary Fig. 1) and the EtBr accumulation assay showed no effect of CTB on membrane permeability. This could be due to inherent differences between these bacteria in their membrane architecture.

C. jejuni is known to stochastically vary expression of its surface structures through changes in the homopolymeric nucleotide tract length within specific genes resulting in frequent frameshifts and premature stop codons during replication. This effectively leads to “on/off-switching” of genes containing these tracts, many of which are involved in surface glycan biosynthesis and transfer affording C. jejuni the ability to rapidly shift the composition and diversity of surface structures in that community. Alterations in these structures has been shown to reduce the susceptibility of C. jejuni to serum, bacteriophages48 and anti-microbial peptides37,38. As well, even small changes in LOS have been shown to have a profound effect on C. jejuni invasiveness38. By encoding a polyguanosine tract in the cgtB gene, strain C. jejuni 11168 varies the expression of the galactosyltransferase responsible for addition of the LOS terminal galactose. Those cells expressing “off-switched” cgtB will thus present the GM2 ganglioside epitope as opposed to that of GM1. This study demonstrates that LOS from CTB-exposed cells is substantially reduced in CTB binding, and that these cells display off-switched cgtB expression at the poly-G tract. Together these results indicate that CTB and LTB select against GM1 epitope expression by C. jejuni. Interestingly, we also found that pre-incubation with CTB for less than two cell divisions was sufficient to decrease the virulence of C. jejuni in a G. mellonella model. This not only suggests that expression of the GM1 ganglioside in wax moth larvae is important for virulence, but also shows that CTB binding to C. jejuni has consequences on the biology of the organism that extend beyond growth inhibition in vitro.

Since our studies demonstrated that there is an abundance of ganglioside structures in the chicken intestine, it was unexpected, but reasonable to find many ganglioside-mimicking bacteria existing in this environment. Investigation of chicken cecal cross-sections identified bacteria that were readily labeled by both CTB and by α-GM1 antibodies, indicating the presence of other ganglioside receptors and possibly fucosylated structures. Additionally, the CTB bound abundantly to the mucus and goblet cells, which were not bound by α-GM1 antibody. This binding was largely abrogated by the addition of an α1-2-fucosidase to cross-sections prior to fluorescence detection, indicating that CTB binding to these structures was mediated through its fucose-binding domain. In support of this hypothesis, fucose is known to be abundant in mucins and in goblet cells producing mucin49. Remarkably, both CTB and the α-GM1 antibodies also bound extensively to bacteria in the intestinal lumen, suggesting that there are other bacteria present in the chicken gut that display antigens resembling GM1 gangliosides. Ganglioside mimicry is a phenomenon thought to be rare in bacteria, and as described earlier, can lead to autoimmune disease in humans. Therefore, the observation that other ganglioside-mimicking bacteria are prevalent in food animals warrants further investigation into their identity and into the nature of the glycoconjugates they display.

Given the broad distribution of GM1 ganglioside-mimicking bacteria among the gut microbiota of chickens, we hypothesized that the administration of AB5 toxins would alter the microbial composition. The most striking impact we observed was the decrease in microbes in the Firmicutes phylum, which represents a major component of the chicken gut microbiome. We were also able to isolate a member of the Firmicutes, E. gallinarum/casseliflavus, from the chicken gut based on its ability to mimic GM1-ganglioside. Interestingly, E. gallinarum has recently been associated with another autoimmune disease, systemic lupus erythematosus50. Other researchers have also observed gut microbiome changes following V. cholerae infection51,52. Hsiao et al. showed that V. cholerae infection correlated to an unhealthy microbiome, leading to long-lasting effects on gut microbial composition even after the infection had subsided51,52 while Monira et al. linked V. cholerae infection to increases in Proteobacteria and decreases in other phyla, including Firmicutes52. In the published studies, it is not possible to distinguish between direct toxin effects on the gut microbiota vs consequences of the pathological process; however, the sole administration of the toxin B-subunits used in our studies does not induce pathology45, suggesting that these AB5 toxins could directly provide a competitive advantage for those that produce them through growth inhibition or simply reduced colonization. It may be particularly important for AB5 toxin-producers to target ganglioside-mimicking bacteria due to the fitness that mimicry imparts in dealing with host defenses37,38. This would make AB5 toxins particularly useful tools in the microbiome and supports the notion that these toxins did not only (or primarily) evolve to target the host, but instead increase competitiveness of the producers as colonizers of the gastrointestinal tract.

The evidence that other gut bacteria have the capacity to mimic GM1 gangliosides and that AB5 toxins may influence these species has other implications for human health. As mentioned above, ganglioside mimicry is closely linked to the development of GBS, but not all persons infected with GM1-mimicking C. jejuni develop the disease. It is possible that other ganglioside-mimicking bacteria could be present in our gut or appear transiently through ingestion of poultry products and could impact individual disease susceptibility by either immune tolerizing or training. Further studies into the extent to which other bacteria presenting these antigens contribute to the manifestation of GBS are warranted. It is also relevant that CTB is currently administered as part of an increasing number of health-promoting strategies including use in the oral cholera vaccine, as a toxoid adjuvant (with unexpected cross-reactivity to the C. jejuni major outer membrane protein53), and recently as an anti-inflammatory agent for treatment of diseases such as diabetes mellitus and atherosclerosis54. Taken together, our studies identify a new role for AB5 toxins and may explain why some organisms have developed mechanisms to vary their ganglioside mimics. We demonstrate that the chicken gut is rich in ganglioside structures derived from the host and the resident microbiota may impact both bacterial competition and human health.

Methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

The C. jejuni strains used in this study were grown on NZCYM agar (Difco) under microaerobic conditions (85% N2, 10% CO2 and 5% O2) at 37 °C. The E. coli strains were grown on LB agar under atmospheric conditions at 37 °C. Mutant strains were grown in media supplemented with ampicillin (50 μg mL−1) and/or kanamycin (25 μg mL−1). Table 1 lists the bacterial strains used in this study along with their sources.

To create the C. jejuni 11168 ΔcgtB mutant, primers cgtB-mut-F-XhoI and cgtB-mut-R-SacI (Supplementary table 1) were used to PCR-amplify the cgtB gene from C. jejuni 11168. The fragment was then ligated into pGEM®-T Easy Vector (Promega) and primers InvPCR-cgtB-F-BamHI and InvPCR-cgtB-R-BamHI (Supplementary table 1) were used to perform inverse PCR to introduce a BamHI site into cgtB. The kanamycin cassette was isolated from the pMW2 plasmid by BamHI digest and inserted into cgtB. In the case of the ΔneuC1 mutant, primers neuC1F15 and neuC1R984 (Supplementary table 1) were used to amplify the gene out of C. jejuni 11168. The PCR product was ligated into pPCR-Script Amp and a kanamycin resistance cassette from pILL600 was inserted into the NdeI restriction site present within the gene. Next, for both mutants, C. jejuni 11168 cells were grown on kanamycin (50 μg mL−1) selective agar. The resulting colonies were evaluated for insertion of the kanamycin cassette by PCR and sequencing. For the ΔcmeA mutant, plasmid pET22b Cf-CmeA55 was linearized using SpeI and blunt-ended with T4 DNA polymerase. The cat cassette was obtained from plasmid pRY109 after SmaI digestion. After ligation, the correct orientation of the cassette in cmeA was confirmed by sequencing of candidate plasmids with primers CmeA-F and CmeA-R (Supplementary table 1). These primers were then used to amplify cmeA::cat by PCR. The purified PCR product was used to transform strain 11168 by natural transformation. CmR clones were analyzed by PCR for the correct insertion of the cassette into the chromosome with CmeA-os-R and CmeA-os-F (Supplementary table 1). Absence of CmeA in the mutant was also confirmed by western blotting with CmeA-specific antibodies.

Immunogold labeling and transmission electron microscopy

Following growth of C. jejuni or E. coli overnight, cells were harvested in NZCYM or LB broth, respectively, and their optical density at 600 nm (OD600) was adjusted to 0.5 for C. jejuni or 1.0 for E. coli. Then, 2 μL of CTB (1 mg mL−1, Sigma) was added to 2 mL of each cell suspension. The suspensions were incubated under normal growth conditions for each organism for 1 h and then centrifuged at 6,000 × g for 4 min Cell pellets were washed and resuspended in PBS. Immunogold labeling and transmission electron microscopy were carried out as described in previous reports with minor modifications19,56. Briefly, Formvar-coated copper grid was floated on top of the cell suspension for 1 h. Grids were then floated on blocking solution (PBS with 5% bovine serum albumin) for 1 h to block, followed by 1:50 rabbit α-CT antibodies (Fitzgerald Industries International) (in blocking solution) for 1 h, and goat α-rabbit IgG conjugated to 10-nm gold particles (BB International, diluted 1:50 in blocking solution) for 2 h, washing 3 times in blocking solution after each step. The grids were then examined by transmission electron microscopy (Philips Morgagni 268; FEI Company) and images were taken using a charge-coupled camera and controller (Gatan) and processed using DigitalMicrograph (Gatan).

Bacterial clearance assay

The effect of the holotoxins and toxin subunits on bacterial growth was examined by spotting CT, CTA, CTB or LTB onto cell-containing double layer agar plates prepared using the standard overlay agar method commonly used in bacteriophage plaque assays57. C. jejuni HS:19, 11168, and HS:3 strains or E. coli CWG 308 and CWG308 pGM1a/pCst were grown overnight and harvested in NZCYM or LB broth and adjusted to an OD600 of 0.1. Then, 200 μL of this suspension was mixed with 5 mL of 0.6% molten NZCYM or LB agar and poured onto a previously solidified and pre-warmed NZCYM or LB agar plate containing 1.5% agar. The molten agar layer was allowed to solidify at RT for 15 min and then 2–5 μL of toxin (1 mg mL−1), or toxin mixed 1:1 with competitive binding glycan (both at 1 mg mL−1) in the case of competitive inhibition assays, was spotted onto the agar surface. For the concentration determination assay, CTB was diluted with Milli-Q H2O to contain 5, 1, 0.5, or 0.25 μg in 5 μL spotted onto C. jejuni HS:19. These plates were incubated agar-side-down for 18–24 h under normal growth conditions as described above and imaged using a GO21 camera connected to an Olympus SZX16 stereoscope.

Scanning electron microscopy

Following a clearance assay with CTB on C. jejuni HS:19 as described above, agar squares were excised from inside, outside or at the interface of the clearance zones and prepared using the following established protocol58. The squares were excised using a scalpel and trimmed to leave only the top layer of agar (about 2 mm) and then incubated in scanning electron microscopy (SEM) fixative (2.5% glutaraldehyde; 2% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer) overnight at 4 °C. Excised squares were then washed in 0.1 M phosphate buffer three times for 10 min and dehydrated using a series of 15 min washes: 50% ethanol, 70% ethanol, 90% ethanol, 100% ethanol, ethanol: hexamethyldisilazane (HMDS) 75:25, ethanol:HMDS 50:50, ethanol:HMDS 25:75 and 100% HMDS. After leaving HMDS to evaporate overnight, the excised squares were mounted onto SEM stubs and sputter-coated with the Hummer sputtering system (Anatech Ltd.). The squares were then imaged using the Phillips/FEI (XL30) scanning electron microscope (Philips/FEI) with an electron beam energy of 20 kV.

Isolation of C. jejuni LOS from clearance zones

Following a clearance assay with CTB or LTB, sections of agar were excised using a scalpel from either inside or outside the observed clearance zone, and the agar sections were incubated for 15 min at RT to elute the embedded cells. The eluate was then transferred to a new tube and centrifuged at 6000 × g for 4 min to collect the cells. The pellet was resuspended in 100 μL of PBS, spread onto NZCYM plates and incubated under microaerobic conditions at 37 °C overnight. The cells were then harvested in 500 μL PBS, centrifuged at 18,300 × g for 90 s and resuspended in 50 μL sample buffer (100 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0), 2% β-mercaptoethanol, 4% SDS, 0.2% bromophenol blue, 0.2% xylene cyanol, 20% glycerol). This mixture was boiled for 10 min at 95 °C and cooled to RT before adding 47.5 μL additional sample buffer with 2.5 μL proteinase K (20 mg mL−1) and incubating overnight at 37 °C. The following day, the proteinase K was inactivated by heating to 65 °C for 1 h and the samples were either loaded directly onto an SDS-PAGE gel or stored at −20 °C.

Silver staining of LOS

After isolation of LOS, the samples were separated by SDS-PAGE using 15% SDS-PAGE. The gel was then silver-stained according to the method described by Tsai and Frasch (1982) with a few modifications59. The separated gels were immediately immersed in fixing solution (55% Milli-Q H2O, 40% ethanol, 5% acetic acid) and incubated for at least 1.5 h. The gels were then rinsed 4 times and washed twice for 5 min in Milli-Q H2O before being placed in oxidizing solution (fixing solution with 0.7% periodic acid) for 10 min After rinsing 4 times and washing twice for 5 min in Milli-Q H2O, the gels were immersed in pre-stain solution (18.67 mM NaOH, 1.3% NH4OH in Milli-Q H2O) for 10 min, then stained with staining solution (pre-stain solution with 39.2 mM silver nitrate). Following 4 rinses and 2 washes for 10 min in Milli-Q H2O, development was done using the BioRad Silver Stain Developer as directed and development was stopped by adding stopping solution (5% acetic acid in Milli-Q H2O).

Far western blot of LOS and cgtB sequencing

After isolation of the LOS as described above, the samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and the gel was transferred to a PVDF membrane overnight at 30 V at 4 °C. The membrane was then blocked with 5% skim milk/PBST for 1 h, probed with CTB (1:100,000) for 1 h, washed 3 × 10 min in PBST, probed with rabbit α-CT antibodies (1:6,500) for 1 h, washed 3 × 10 min PBST, and probed with goat α-rabbit-HRP antibodies (1:20,000) for 1 h. The membrane was developed using a chemiluminescent substrate mix (Western LightningTM Plus-ECL from PerkinElmer) and images were captured using X-ray development film (Kodak).

Cells were isolated from inside and outside the clearance zones of agar using the same method as was described for the isolation of LOS. For DNA isolation, once the isolated C. jejuni 11168 cells were grown on NZCYM, cells were resuspended in 500 μL of TE Buffer (10 mM Tris- HCL pH 8.0, 0.1 mM EDTA in Milli-Q H2O) and centrifuged at 18,300 × g for 2 min. The pellet was resuspended in 0.2 mL Buffer TE and genomic DNA was isolated using the Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Fermentas) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The cgtB gene was amplified using Vent polymerase (NEB) and the primers described by Linton et al.:22 DL39 and DL41 (Supplementary table 1). The resulting solution was purified using the GeneJETTM Gel Purification Kit (Fermentas) as instructed by the manufacturer. The purified PCR product was then sequenced using the reverse primer 1139R (Supplementary table 1) with sequencing services offered by the Molecular Biology Service Unit at the University of Alberta.

Ethidium bromide accumulation assay

The ethidium bromide (EtBr) accumulation assay was performed using the following established protocol30. C. jejuni 11168 wildtype, ΔcgtB, ΔcmeA, ΔneuC1 cells, as well as E. coli CWG 308 and pGM1/pCst were harvested from agar plates in PBS and adjusted to OD600 = 0.2. The cells were then incubated with CTB (50 μg mL−1) for 30 min at 37 °C before adding EtBr to a final concentration of 1.875 μg mL−1. The accumulation of EtBr was measured by relative fluorescence every 2 min over a total of 20 min using the Bio Tek Synergy H1 plate reader with an excitation wavelength of 530 nm and emission wavelength of 600 nm. This experiment included 7 biological replicates for 11168 wildtype, 4 for ΔcgtB, ΔcmeA and ΔneuC1, and 3 for both of the E. coli strains. Each biological replicate included 3 technical replicates.

Galleria mellonella infection assay

The Galleria mellonella wax moth model was used as a model to assess C. jejuni virulence similar to what has previously been done60. C. jejuni HS:19 was suspended in 10 mM MgSO4 solution to an OD600 = 1.0 (~1.0 × 109). The cell suspensions were then mixed with either MgSO4, or CTB to a final concentration of 50 μg mL−1, and incubated for 4 h at 37 °C. Following this incubation, cell counts were verified by serial dilution plating and 5 μL of suspension or control MgSO4 was injected into the hind leg of the wax moth larvae (Backwater Reptiles Inc.). The larvae were incubated at 37 °C for 5 days before counting the proportion of dead and alive moths. The G. mellonella incubation time coincides with growth curves established to determine time needed for C. jejuni HS:19 to cause mortality. This experiment included 3 biological replicates for both HS:19 and HS:19 + CTB, 2 for MgSO4 and 1 for CTB. Each biological replicate included 3 technical replicates.

Chicken studies

Commercial broiler chickens (Ross 308, Avigen) were obtained on the day of hatch from Lilydale, Edmonton. Upon arrival, birds were divided into groups with up to 9 chickens each. The birds were orally gavaged with PBS, PBS + CTB, or PBS + LTB initially on day 30, then again 8 h and 12 h later using 100 μg of toxin per 300 μL gavage. The birds were then euthanized on day 31 and both ceca were removed and processed immediately. All animal studies were carried out in accordance with the protocol approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Alberta, protocol number AUP00003.

Fluorescence microscopy

Intact chicken ceca were soaked in fresh Carnoy's fixative (60% ethanol, 30% chloroform, 10% glacial acetic acid) for 2 h and then moved to 100% ethanol. They were then cut into appropriate sized cross-sections with a scalpel, anchored in tissue cassettes and stored in 70% ethanol prior to embedding. Paraffin embedding involved sequential ethanol dehydration steps: 1 h in 70% ethanol, 1 h in 90% ethanol, 1.5 h in 100% ethanol, 1.5 h in 100% ethanol, 1.25 h in ethanol:toluene (1:1), followed by 2 × 0.5 h in 100% toluene. The specimen was then put in two wax treatments for 2 h each and embedded the following morning in paraffin.

Immunofluorescent staining of the paraffin-embedded sections was conducted using the following established protocols61. Tissue sections were deparaffinized using 5 min washes in xylene (4×), 100% ethanol (2×), 95% ethanol, 70% ethanol and dH2O. Antigen retrieval was performed by steaming slides for 30 min in sodium citrate buffer (10 mM Sodium Citrate, 0.05% Tween 20, pH 6.0). Slides were blocked for 1 h using blocking buffer (PBS containing: 0.2% Triton X-100, 0.05% Tween, 1% bovine serum albumin, 5% donkey serum). Where indicated, slides were treated with α1-2-fucosidase (NEB, P0724S) following antigen retrieval in sodium citrate buffer, but prior to blocking with donkey serum buffer. Slides were treated for 1 h, with 1 μl (20 units) of α1-2-fucosidase in 10 μl of 1× Glycobuffer (supplied by the manufacturer), at 37 °C, followed by a PBS wash. Each slide was then treated with CTB (1 mM, Sigma, Cat. No. C9903) for 1 h, followed by either α-CTB antibody (1:100) or α-GM1 antibody (1:100, Abcam) for 1 h. Slides were visualized using Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated donkey α-rabbit IgG (1:1000, Invitrogen). The tissues were mounted using ProLong Gold antifade reagent containing DAPI (Invitrogen). The stained slides were viewed using a Zeiss AxioImager Z1, and photographed using an AxioCam HRm camera with AxioVision software.

Whole cell surface staining of GM1 pull-down candidates was performed as follows: isolated bacteria were harvested from their respective growth media and adjusted to OD600 = 1.0. Cells from 100 µl were pelleted by centrifugation (1 min, 13,000 rpm), suspended in 1 ml blocking solution (PBS, 5% skim milk) and incubated on ice for 30 min Cells were subsequently probed with either α-GM1 (1:1000 in PBS; Abcam, Cat. No. 23943) or CTB (1 mM) in combination with α-CTB (1:1000 in PBS; Biorad, Cat. No. 2060–0020) and Alexa Flour-488 conjugated α-rabbit antiserum (1:500 in PBS; Invitrogen, Cat # A-11008). Each incubation was done on ice for 20–30 min and three washes with 1 ml PBS were performed in between antibody incubations. Cells were counterstained with DAPI (1 μg mL−1), mounted on glass slides and analyzed on a DeltaVision fluorescent microscope equipped with a sCMOS camera.

16S rRNA sequence analysis of chicken ceca

DNA isolation and 16S rRNA tag sequence analysis of bacterial DNA isolated from chicken cecal samples was performed using the following established protocol62. DNA was amplified using the 926F and 1392R universal primers (Supplementary table 1) that target the V6 to V8 region of the 16S ribosomal RNA gene. The PCR conditions used are described in 16S Metagenomic Sequencing Library Preparation (Illumina®, San Diego, CA). Sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene was completed with an Illumina MiSeq Sequencer using MiSeq Reagent kit V3 (Illumina). Reads were trimmed to 290 bp with the FASTX-Toolkit (http://hannonlab.cshl.edu/fastx_toolkit/), and paired-end reads were merged with the merge-illumina-pairs application (https://github.com/meren/illumina-utils/). Sequences between 440 and 470 nucleotides long were selected for analysis. To standardize the sequencing depth across samples, sequences were subsampled to 45,000 reads using Mothur v.1.35.1. Subsequently, USEARCH v8.1.1861 was used to generate operational taxonomic units (OTUs) with a 98% similarity cut-off. OTU generation included the removal of putative chimeras identified against the Gold reference database, in addition to the chimera removal inherent to the OTU clustering step in UPARSE. The resulting reads were assigned to different taxonomic levels from Phylum to Genus using a parallelized version of CLASSIFIER (rdp_classifier_v2.10.1) from the Ribosomal Database Project (RDP). Taxonomic assignment for the OTUs was obtained using the “Identify” function in EZbiocloud63. Sequences whose identity was lower than 97% were classified using the Classifier and SeqMatch functions in Ribosomal Database Project webpage64,65. The number of reads in each taxonomic bin was normalized to the proportion of the total number of reads per each sample for statistical analyses. To achieve normality for the microbiome data that were not normally distributed, values were subjected to log10 transformations. Diversity analyses were done using MacQIIME version 1.9.166.

Identification of GM1-mimicking bacteria from ceca

Chicken cecal contents were resuspended in PBS to a concentration of 1 mg mL−1. To address non-specific binding, the mixture was further diluted 1:5 with PBS-T containing 2% skim milk and incubated in a gravity flow column with 500 μL protein G agarose (Sigma) for 10–15 min at room temperature. Samples were mixed every 2–3 min, the flow-through was collected and incubated with 5 μL of α-GM1 antibody on ice for 15 min, mixing regularly. The suspension was then passed through a gravity flow column containing 500 μL of protein G agarose. After two washes with PBS-T, 2% skim milk and PBS-T and one final wash with PBS (5 mL each), protein G agarose beads were recovered with 1 mL PBS and 50 µL of a 5-fold serial dilution series were plated on either Brain Heart infusion (BHI), De Man, Rogosa and Sharpe (MRS), or Yeast, Casitone-Fatty Acid (YCFA) agar. Plates were incubated microaerobically or anaerobically at 37 °C for up to 72 h. Colonies were picked, isolated and tested for GM1 ganglioside antibody reactivity by whole cell ELISA followed by GM1 and CTB binding by fluorescence microscopy. One GM1 and CTB-reactive bacterial species was further identified by 16S rRNA gene sequencing with oligonucleotides 926R, 515F, 1068F, 1391R, and 519R (Supplementary table 1) after PCR-amplification of the 16S rRNA gene from extracted DNA with oligonucleotides 27F and 1492R (Supplementary table 1).

GM1 antibody and lysis solution spot assay

These spot assays were performed in the same way as the others with minor changes. For the GM1 ganglioside antibody spot assay, 2 μL of the antibody (Abcam) or 2 μg of CTB was spotted directly onto the cells prior to growth. For the lysis buffer spot assay, 2 μL of lysis buffer (undiluted from Thermo Scientific GeneJET Plasmid Miniprep Kit) or 2 μg of CTB was spotted onto cells after growth for 24 h.

Statistics

For the EtBr accumulation and Galleria mellonella data, two-tailed, unpaired t-tests were performed to compare the relative fluorescence upon addition of EtBr, and C. jejuni HS:19 infection with and without CTB respectively. For microbiome analyses, two-tailed Mann Whitney tests were performed for the CTB dataset comparisons, while two-tailed unpaired t-tests with Welch's correction or multiple t-tests were performed for the LTB comparisons using Graph Pad Prism version 7. The Adonis PERMANOVA test was performed on NMDS plots using the statistical software R version 3.3.1 (http://www.r-project.org/).

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Brandi Davis and Yee Ying Lock for preparation of samples for 16S rRNA sequencing, Arlene Oatway for help with preparing cecal samples for electron microscopy, the Molecular Biology Services Unit at the University of Alberta for performing the Sanger sequencing reactions and Drs. James and Adrienne Paton for providing us with their E. coli CWG 308 wildtype and pGM1/pCst strains. We also thank Dr. Xiaoming Bian and Dr. Hanwen Huang for statistical advice, Dr. Xiaorong Lin for the use of her stereoscope, and Dr. Stefan Pukatzki and Dr. Michel Gilbert for helpful discussions. This study was funded in part by fellowships to RTP from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and Alberta Innovates Health Solutions. C.M.S. is an Alberta Innovates Strategic Chair in Bacterial Glycomics. J.W. is a CAIP Chair in Nutrition, Microbes, and Gastrointestinal Health. B.A.V. is the CH.I.L.D. Foundation Chair in Pediatric Gastroenterology.

Author contributions

R.T.P., M.S., M.E.P., H.N., C.Q.W. performed the experiments. All authors contributed to the writing of the paper. R.T.P., J.S., and C.M.S. conceived the original idea. C.C., J.W., B.A.V., and C.M.S. supervised the project.

Data availability

All relevant data are available from the corresponding author. The source data underlying Figures 4a-b, 5a-b and 7, and Supplementary Figures 1c-d, 3 and 4 are provided as a Source Data file. The 16S rRNA datasets generated and analyzed during these studies are available in the NCBI SRA repository under BioProject PRJNA522915; the BioSamples accession numbers are listed in Supplementary table 2.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Journal peer review information: Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-019-09362-z.

References

- 1.Krinos C, et al. Extensive surface diversity of a commensal microorganism by multiple DNA inversions. Nature. 2001;414:555–558. doi: 10.1038/35107092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moran AP, O'Malley DT. Potential role of lipopolysaccharides of Campylobacter jejuni in the development of Guillain-Barré syndrome. J. Endotoxin Res. 1995;2:233–235. doi: 10.1177/096805199500200401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yuki N, et al. A Bacterium Lipopolysaccharide that Elicits Guillain-Barré Syndrome has a GM1 Ganglioside-Like Structure. J. Exp. Med. 1993;178:1771–1775. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.5.1771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Comstock LE, Kasper DL. Bacterial glycans: Key mediators of diverse host immune responses. Cell. 2006;126:847–850. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yi W, et al. Escherichia coli O86 O-antigen biosynthetic gene cluster and stepwise enzymatic synthesis of human blood group B antigen tetrasaccharide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:2040–2041. doi: 10.1021/ja045021y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang Y, Nizet V. The interplay between Siglecs and sialylated pathogens. Glycobiology. 2014;24:818–825. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwu067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stowell SR, et al. Innate immune lectins kill bacteria expressing blood group antigen. Nat. Med. 2010;16:295–U90. doi: 10.1038/nm.2103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wesener DA, et al. Recognition of microbial glycans by human intelectin-1. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2015;22:603–610. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Propheter DC, Chara AL, Harris TA, Ruhn KA, Hooper LV. Resistin-like molecule beta is a bactericidal protein that promotes spatial segregation of the microbiota and the colonic epithelium. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:11027–11033. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1711395114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ali M, Nelson AR, Lopez AL, Sack DA. Updated global burden of cholera in endemic countries. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2015;9:e0003832. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beddoe T, Paton AW, Le Nours J, Rossjohn J, Paton JC. Structure, biological functions and applications of the AB5 toxins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2010;35:411–418. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spangler BD. Structure and function of cholera-toxin and the related Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin. Microbiol. Rev. 1992;56:622–647. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.4.622-647.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bharati K, Ganguly NK. Cholera toxin: a paradigm of a multifunctional protein. Indian J. Med. Res. 2011;133:179–187. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanchez J, Holmgren J. Cholera toxin structure, gene regulation and pathophysiological and immunological aspects. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2008;65:1347–1360. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-7496-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang RG, et al. The 3-dimensional crystal-structure of cholera-toxin. J. Mol. Biol. 1995;251:563–573. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lencer WI, Tsai B. The intracellular voyage of cholera toxin: going retro. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2003;28:639–645. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacKenzie CR, Hirama T, Lee KK, Altman E, Young NM. Quantitative analysis of bacterial toxin affinity and specificity for glycolipid receptors by surface plasmon resonance. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:5533–5538. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.9.5533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holmgren J, Lonnroth I, Mansson J, Svennerholm L. Interaction of cholera toxin and membrane GM1 ganglioside of small-intestine. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1975;72:2520–2524. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.7.2520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wands AM, et al. Fucosylation and protein glycosylation create functional receptors for cholera toxin. eLife. 2015;4:e09545. doi: 10.7554/eLife.09545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El-Hawiet A, Kitova EN, Klassen JS. Recognition of human milk oligosaccharides by bacterial exotoxins. Glycobiology. 2015;25:845–854. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwv025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heggelund JE, et al. High-resolution crystal structures elucidate the molecular basis of cholera blood group dependence. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:e1005567. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Linton D, et al. Phase variation of a beta-1,3 galactosyltransferase involved in generation of the ganglioside GM1-like lipo-oligosaccharide of Campylobacter jejuni. Mol. Microbiol. 2000;37:501–514. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Butzler JP. Campylobacter, from obscurity to celebrity. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2004;10:868–876. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2004.00983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amour C, et al. Epidemiology and Impact of Campylobacter Infection in Children in 8 Low-Resource Settings: Results From theMAL-ED Study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016;63:1171–1179. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moran AP, Rietschel ET, Kosunen TU, Zahringer U. Chemical Characterization of Campylobacter jejuni Lipopolysaccharides Containing N-Acetylneuraminic Acid and 2,3-Diamino-2,3-Dideoxy-D-Glucose. J. Bacteriol. 1991;173:618–626. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.2.618-626.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parker C, et al. Comparison of Campylobacter jejuni lipooligosaccharide biosynthesis loci from a variety of sources. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005;43:2771–2781. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.6.2771-2781.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gilbert, M., Parker, C. T., Moran, A. P. Campylobacter jejuniLipooligosaccharides: Structures and Biosynthesis. Campylobacter, 3rd edn. 483–504. (ASM Press, Washington, DC, 2008).

- 28.Shahrizaila, N., Yuki, N. Guillain-Barré syndrome animal model: the first proof of molecular mimicry in human autoimmune disorder. J. Biomed. Biotech. 10.1155/2011/829129 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Aspinall GO, McDonald AG, Pang H, Kurjanczyk LA, Penner JL. Lipopolysaccharides of Campylobacter jejuni serotype O:19: Structures of core oligosaccharide regions from the serostrain and two bacterial isolates from patients with the Guillain-Barré syndrome. Biochemistry. 1994;33:241–249. doi: 10.1021/bi00167a032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin J, Michel L, Zhang Q. CmeABC functions as a multidrug efflux system in Campylobacter jejuni. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002;46:2124–2131. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.7.2124-2131.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Storek KM, et al. Monoclonal antibody targeting the β-barrel assembly machine of Escherichia coli is bactericidal. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:3692–3697. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1800043115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Senior NJ, et al. Galleria mellonella as an infection model for Campylobacter jejuni virulence. J. Med. Microbiol. 2011;60:661–669. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.026658-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Akashi N, et al. Production of heat-stable enterotoxin II by chicken clinical isolates of Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1993;109:311–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1993.tb06186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsuji T, Joya J, Honda T, Miwatani T. A Heat-Labile Enterotoxin (Lt) Purified from Chicken Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli is Identical to Porcine Lt. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1990;67:329–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1990.tb04042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilson BA, Salyers AA, Whitt DD, Winkler ME. Bacterial Pathogenesis: A Molecular Approach. 3rd edn. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 2011. Chapter 12: Toxins and other toxic virulence factors; pp. 225–253. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Waldor MK, Mekalanos JJ. Lysogenic conversion by a filamentous phage encoding cholera toxin. Science. 1996;272:1910–1914. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5270.1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guerry P, Ewing CP, Hickey TE, Prendergast MM, Moran AP. Sialylation of lipooligosaccharide cores affects immunogenicity and serum resistance of Campylobacter jejuni. Infect. Immun. 2000;68:6656–6662. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.12.6656-6662.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guerry P, et al. Phase variation of Campylobacter jejuni 81-176 lipooligosaccharide affects ganglioside mimicry and invasiveness in vitro. Infect. Immun. 2002;70:787–793. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.2.787-793.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Albert M, Faruque A, Faruque S, Sack R, Mahalanabis D. Case-control study of enteropathogens associated with childhood diarrhea in Dhaka, Bangladesh. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1999;37:3458–3464. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.11.3458-3464.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lertsethtakarn P, et al. Travelers' diarrhea in Thailand: a quantitative analysis using TaqMan (R) array card. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018;67:120–127. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mudrak B, Kuehn MJ. Heat-labile enterotoxin: beyond GM1 binding. Toxins. 2010;2:1445–1470. doi: 10.3390/toxins2061445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oh J, et al. Isolation and epidemiological characterization of heat-labile enterotoxin-producing Escherichia fergusonii from healthy chickens. Vet. Microbiol. 2012;160:170–175. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2012.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Akond MA, Alam S, Hasan SMR, Shirin M. Distribution of Vibrio cholerae and its antibiotic resistance in the samples from poultry and poultry environment of Bangladesh. Adv. Environ. Biol. 2009;3:25–32. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bohaychuk VM, et al. Occurrence of pathogens in raw and ready-to-eat meat and poultry products collected from the retail marketplace in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. J. Food Prot. 2006;69:2176–2182. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-69.9.2176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Holmgren J, Czerkinsky C, Lycke N, Svennerholm A. Strategies for the Induction of Immune-Responses at Mucosal Surfaces Making use of Cholera-Toxin-B Subunit as Immunogen, Carrier, and Adjuvant. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1994;50:42–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cordero RJB, et al. Antibody Binding to Cryptococcus neoformans Impairs Budding by Altering Capsular Mechanical Properties. J. Immunol. 2013;190:317–323. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nikaido H. Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability revisited. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2003;67:593–656. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.4.593-656.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sorensen MCH, et al. Phase variable expression of capsular polysaccharide modifications allows Campylobacter jejuni to avoid bacteriophage infection in chickens. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2012;2:11. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stahl M, et al. L-Fucose utilization provides Campylobacter jejuni with a competitive advantage. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:7194–7199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014125108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vieira SM, et al. Translocation of a gut pathobiont drives autoimmunity in mice and humans. Science. 2018;359:1156–1160. doi: 10.1126/science.aar7201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hsiao A, et al. Members of the human gut microbiota involved in recovery from Vibrio cholerae infection. Nature. 2014;515:423–426. doi: 10.1038/nature13738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Monira S, et al. Metagenomic profile of gut microbiota in children during cholera and recovery. Gut Pathog. 2013;5:1. doi: 10.1186/1757-4749-5-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Albert MJ, Mustafa AS, Islam A, Haridas S. Oral Immunization with Cholera Toxin Provides Protection against Campylobacter jejuni in an Adult Mouse Intestinal Colonization Model. mBio. 2013;4:e00246–13. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00246-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Baldauf KJ, Royal JM, Hamorsky KT, Matoba N. Cholera Toxin B: One Subunit with Many Pharmaceutical Applications. Toxins. 2015;7:974–996. doi: 10.3390/toxins7030974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Linton D, et al. Functional analysis of the Campylobacter jejuni N-linked protein glycosylation pathway. Mol. Microbiol. 2005;55:1695–1703. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Javed MA, et al. A receptor-binding protein of Campylobacter jejuni bacteriophage NCTC 12673 recognizes flagellin glycosylated with acetamidino-modified pseudaminic acid. Mol. Microbiol. 2015;95:101–115. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sorensen MCH, et al. Bacteriophage F336 Recognizes the Capsular Phosphoramidate Modification of Campylobacter jejuni NCTC11168. J. Bacteriol. 2011;193:6742–6749. doi: 10.1128/JB.05276-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Javed MA, Sacher JC, van Alphen LB, Patry RT, Szymanski CM. A Flagellar Glycan-Specific Protein Encoded by Campylobacter Phages Inhibits Host Cell Growth. Virus.-Basel. 2015;7:6661–6674. doi: 10.3390/v7122964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tsai C, Frasch C. A Sensitive Silver Stain for Detecting Lipopolysaccharides in Polyacrylamide Gels. Anal. Biochem. 1982;119:115–119. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(82)90673-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.van Alphen LB, et al. Biological Roles of the O-Methyl Phosphoramidate Capsule Modification in Campylobacter jejuni. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87051. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stahl M, et al. A Novel Mouse Model of Campylobacter jejuni Gastroenteritis Reveals Key Pro-inflammatory and Tissue Protective Roles for Toll-like Receptor Signaling during Infection. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004264. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nothaft H, et al. Engineering the Campylobacter jejuni N-glycan to create an effective chicken vaccine. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:26511. doi: 10.1038/srep26511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yoon S, et al. Introducing EzBioCloud: a taxonomically united database of 16S rRNA gene sequences and whole-genome assemblies. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2017;67:1613–1617. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.002404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang Q, Garrity GM, Tiedje JM, Cole JR. Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007;73:5261–5267. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00062-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cole JR, et al. Ribosomal Database Project: data and tools for high throughput rRNA analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D633–D642. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Caporaso JG, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods. 2010;7:335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Penner JL, Hennessy JN, Congi RV. Serotyping of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli on the Basis of Thermostable Antigens. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1983;2:378–383. doi: 10.1007/BF02019474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Thibault P, et al. Identification of the carbohydrate moieties and glycosylation motifs in Campylobacter jejuni flagellin. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:34862–34870. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104529200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]