Abstract

Aims

Patients with heart failure (HF) are known to have a reduced pulmonary diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO), but little is known about how lung function relates to central haemodynamics. The aim of this study was to investigate the association between haemodynamic variables and pulmonary diffusion capacity adjusted for alveolar volume in congestive HF patients and to analyse how predicted DLCO/VA affects mortality in relation to the haemodynamic status.

Methods and results

We retrospectively studied right heart catheterization (RHC) and lung function data on 262 HF patients (mean age 51 ± 13 years) with a left ventricular ejection fraction < 45% referred non‐urgently for evaluation for heart transplantation (HTX) or left ventricular assist device (LVAD). Univariate and multivariate linear regression models were constructed to examine the associations between predicted values of DLCO/VA, forced vital capacity (FVC) and forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1), and haemodynamic parameters [pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP), central venous pressure, cardiac index, mean pulmonary artery pressure, and mean arterial pressure] as well as other factors known to affect lung function in HF. FEV1 was reduced to <80% of predicted value in 55% of the population, and DLCO/VA was reduced in 63% of the population. DLCO/VA correlated positively with pulmonary capillary wedge pressure in both univariate and multivariate analyses for all included patients (P < 0.001 and P = 0.045, respectively) and a restricted population of patients with the shortest time between RHC and lung function testing (P = 0.005, P = 0.015). DLCO/VA predicted mortality in multivariate models [hazard ratio 1.5 (1.1–2.1)] but not the combined endpoint of death, LVAD implantation, or HTX. There was no significant correlation between haemodynamics and predicted FVC or FEV1.

Conclusions

Pulmonary diffusion capacity correlates positively with left ventricular fillings pressures, and reduced values predict increased mortality in patients with HF. This might be driven by increased lung capillary volume in patients with pulmonary congestion.

Keywords: Heart failure, Pulmonary diffusion capacity, Right heart catheterization, Haemodynamics

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is frequently associated with functional and structural changes in the lungs. Indeed, lung function abnormalities such as impaired respiratory mechanics and gas exchange can be attributed to HF in the absence of respiratory diseases.1, 2 However, pulmonary co‐morbidities also frequently co‐exist with HF, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a common finding in the HF population.3 The co‐existence of COPD and HF is often a therapeutic and diagnostic challenge in HF management,4 and COPD in patients with HF is associated with a worse clinical status and an increased risk of cardiovascular death and hospitalizations.5 HF‐related changes in pulmonary function are likely multifactorial and explained by interstitial and/or alveolar oedema, increased heart size leading to lung tissue displacement, pulmonary vascular remodelling, and respiratory muscle weakness.6, 7, 8, 9 It is well known that patients with congestive HF (CHF) have a reduction in pulmonary diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO),1 and CHF is known to increase the resistance to gas transfer across the alveolar–capillary membrane.10 Some studies have shown that a reduced diffusion capacity contributes to exercise intolerance11 and is a predictor of mortality in HF patients.12 The mechanism behind these findings, however, is unresolved. It is clear that cardiopulmonary interaction is an important element in HF pathophysiology. Little is known about the association between central haemodynamics and pulmonary diffusion capacity in CHF, and the intention of this article was to investigate the role of haemodynamics in the interaction between heart and lungs. Limited data are available, and the importance of haemodynamic status, particularly pulmonary artery and left ventricular filling pressures for diffusion capacity in advanced HF, is not clear. Nor is it known if an association between DLCO and outcome is driven by haemodynamic abnormalities in these patients. The aim of this study was to investigate the association between haemodynamic variables and pulmonary diffusion capacity adjusted for alveolar volume in CHF patients and to analyse how predicted DLCO/VA affects mortality in relation to the haemodynamic status.

Methods

Patients and study design

This is a retrospective study of HF patients who underwent right heart catheterization (RHC) at the Department of Cardiology at Copenhagen University Hospital, Rigshospitalet, between January 2002 and February 2016. Patients were referred for evaluation for heart transplantation (HTX) or implantation of a left ventricular assist device (LVAD), and optimal medical therapy was instituted before referral. Both hospitalized patients (not in an intensive care unit) and outpatients with advanced CHF were included in this study. If a patient had more than one RHC in the time period, only data from the first catheterization were used. Inclusion criteria were HF with documented left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) less than 45% and a record of pulmonary function tests (PFTs) within 3 months of the RHC. Patients previously treated with LVAD or HTX were excluded from the study. Patients were not required to have symptoms of advanced HF at the time of referral, implying that some patients could be characterized as New York Heart Association (NYHA) Class 2 at the time of RHC. These patients were included as they had recently experienced advanced HF symptoms or their HF condition was considered serious enough to justify referral for investigation including undergoing an invasive cardiac catheterization. Patients were identified in the hospitals' cardiac catheterization database, and data were extracted from this database, as well as from patient medical records and the departments' echocardiography database. The research protocol was approved by the Danish Medical Agency (3‐3013‐1365/1) and the Data Protection Agency (RH 2015‐153). Individual patient consent was not required owing to the retrospective nature of the study.

Haemodynamic evaluation

Right heart catheterization was performed using a Swan–Ganz catheter by four different experienced physicians. All studies were performed in the cardiac catheterization laboratory after appropriate zeroing and calibration of the pressure transducer. The catheter was inserted in the internal jugular or the femoral vein, and the correct placement of the Swan–Ganz catheter was evaluated by fluoroscopy and by visualization of pressure curves on a monitor.

Patients underwent RHC with determination of pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP), pulmonary artery systolic pressure and pulmonary artery diastolic pressure (PADP), mean pulmonary artery pressure (MPAP), central venous pressure (CVP), cardiac output (CO), cardiac index (CI), and mean arterial pressure (MAP). CI was determined as CO divided by the body surface area (BSA). CO was measured by the thermodilution technique. BSA was determined using the DuBois method. MAP was estimated using the formula MAP = [(2 × diastolic blood pressure) + systolic blood pressure]/3. Pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) in Wood units was calculated as PVR = (MPAP − PCWP)/CO. The diastolic pressure gradient (DPG) was calculated as PADP − PCWP, and a DPG ≥ 7 was considered to indicate pulmonary vascular remodelling.13

Pulmonary function tests

To be included in this study, HF patients were required to have documented PFTs performed within 3 months of the RHC. PFTs included spirometry and diffusion capacity. The spirometry was repeated until (at least) three successful and reproducible results were obtained, and it was reported as the highest values achieved.

Diffusion capacity was measured using single‐breath CO technique. Two independent diffusion capacity measurements were performed with a minimum of 4 min intervals. If the results varied <10%, the final result was given as the average value. If the variation was >10%, a third measurement was made and the average of the three measurements was used. All lung function tests were performed in a dedicated laboratory at Rigshospitalet at the Department of Clinical Physiology and Nuclear Medicine. Unless otherwise indicated, lung function variables are expressed as per cent of predicted values14, 15; e.g. per cent forced expiratory volume in 1 second (%FEV1) denotes measured FEV1 divided by expected FEV1 multiplied by 100.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are reported as numbers (n) and percentages (%). Continuous variables are reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD), unless indicated otherwise. We constructed univariate linear regression analyses to examine the associations between FEV1, forced vital capacity (FVC), DLCO/VA, and the haemodynamic parameters (PCWP, MPAP, CVP, CI, MAP, PVR, and DPG). Significant variables were included in multivariable models along with other factors known to affect lung function in HF patients (COPD, diabetes mellitus, and smoking). Two‐sided P values were used; a P‐value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (Version 25, IBM Corp.).

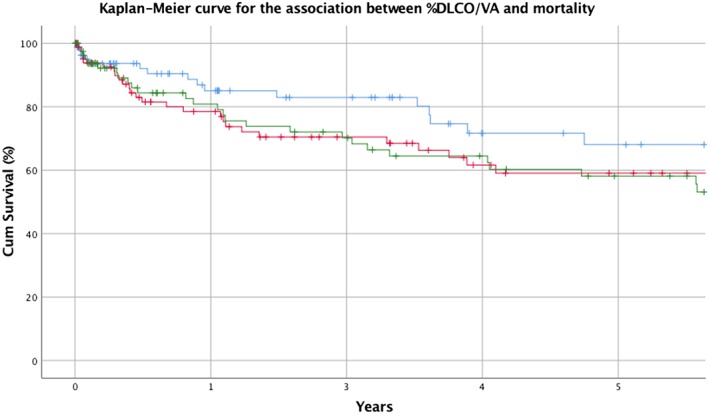

Follow‐up date was set to 1 February 2016. Events were defined as patients being alive at follow‐up date, undergoing LVAD implantation or HTX, or dead. Implantation of an LVAD was used as bridge to transplantation or destination therapy. Kaplan–Meier survival curve was plotted, and Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals. Patients were divided into three groups according to tertiles of %FEV1, %FVC, and %DLCO/VA. Cox regression analyses were performed to identify predictors of death (censoring patients at time of LVAD or HTX) or predictors of the combined endpoint of death, LVAD implantation, or HTX.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 519 patients with LVEF < 45% underwent RHC in the study period, but 257 were excluded owing to missing PFTs within the allowed time frame. Hence, a total of 262 subjects formed the study population. Their characteristics are listed in Table 1. The mean age was 51 years; most were men (78%) and mildly overweight (body mass index = 26.4 kg/m2). The vast majority (91%) had a severely reduced LVEF ≤ 25%, and 64% were in NYHA Class 3 or 4 at the time of examination. One or more clinical signs of congestion such as elevated jugular pressure and peripheral oedema were present in 49% at the time of examination. While 19% were active smokers, the majority were previous smokers (53%). Only 8% were diagnosed with COPD. Most patients were treated with recommended HF medications, although only 68% tolerated beta‐blocker. Only 5% of patients were treated with inotropes at the time of RHC, and none were receiving mechanical circulatory support (as this was an exclusion criterion). Bronchodilators for COPD or asthma were used by 3% of the population.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Total | ||

|---|---|---|

| n = 262 | ||

| n | ||

| Age (years) | 262 | 51 ± 13 |

| Gender (male) | 262 | 204 (78%) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 259 | 26.4 ± 5 |

| NYHA 3 or 4 | 247 | 158 (64%) |

| LVEF ≤ 25% | 262 | 237 (91%) |

| Ischaemic aetiology | 262 | 85 (33%) |

| Risk factors | ||

| Smokinga | 252 | 181 (71.8%) |

| Alcoholb | 262 | 19 (7.3%) |

| Medical history | ||

| COPD | 260 | 20 (7.7%) |

| Diabetes mellitusc | 262 | 45 (17.3%) |

| Clinical signs | ||

| Pleural effusion | 71 | 20 (28.2%) |

| Pulmonary rales | 250 | 38 (15.2%) |

| JVP | 185 | 47 (25.4%) |

| Peripheral oedema | 237 | 67 (28.3%) |

| Ascites | 71 | 20 (28.2%) |

| Hepatomegaly | 154 | 34 (22.1%) |

| S3 gallop | 194 | 234 (17.5%) |

| NT‐pro‐BNP (ng/L) | 86 | 3826 ± 4172 |

| Device therapy | ||

| ICD | 262 | 46 (17.6%) |

| CRT‐D | 262 | 39 (14.9%) |

| CRT‐P | 262 | 11 (4.2%) |

| Pacemaker | 262 | 5 (1.9%) |

| None | 262 | 161 (61.5%) |

| Medication | ||

| ACE inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers | 262 | 201 (76.7%) |

| Beta‐blockers | 262 | 179 (68.3%) |

| Aldosterone receptor antagonists | 262 | 174 (66.4%) |

| Loop diuretics | 262 | 236 (90.1%) |

| Inotropic support | 262 | 14 (5.3%) |

| Resting haemodynamic parameters | ||

| Heart rate (b.p.m.) | 190 | 81 ± 18 |

| Systolic blood pressure (SBP) (mmHg) | 196 | 104 ± 18 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (DBP) (mmHg) | 195 | 65 ± 11 |

| Mean arterial pressure (MAP) (mmHg) | 195 | 78 ± 12 |

| Central venous pressure (CVP) (mmHg) | 256 | 10.9 ± 6.8 |

| Cardiac index (CI) (L/min/m2) | 253 | 2.4 ± 0.7 |

| Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP) (mmHg) | 259 | 20.5 ± 8.4 |

| Mean pulmonary artery pressure (MPAP) (mmHg) | 257 | 28.6 ± 9.9 |

| Pulmonary artery systolic pressure (PASP) (mmHg) | 259 | 42.8 ± 14.5 |

| Pulmonary artery diastolic pressure (PADP) (mmHg) | 257 | 21.5 ± 8.1 |

| Systemic vascular resistance (SVR) (dynes·s/cm5) | 191 | 1250 ± 457 |

| Pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) (dynes·s/cm5) | 253 | 153 ± 115 |

| Diastolic pressure gradient (DPG) | 257 | 1.0 ± 4.1 |

| Pulmonary function tests | ||

| Forced vital capacity (FVC) (L) | 262 | 3.5 ± 1.0 |

| Forced vital capacity (FVC) (% of predicted) | 257 | 81.9 ± 18.9 |

| Forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) (L) | 262 | 2.7 ± 0.8 |

| Forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) (% of predicted) | 262 | 77.3 ± 19.8 |

| FEV1/FVC (% of predicted) | 262 | 76.4 ± 9.0 |

| Pulmonary diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) (mmol/min/kPa) | 259 | 6.3 ± 1.7 |

| Pulmonary diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) (% of predicted) | 258 | 62.6 ± 15.9 |

| Alveolar volume adjusted pulmonary diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO/VA) | 257 | 1.3 ± 0.3 |

| Alveolar volume adjusted pulmonary diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO/VA) (% of predicted) | 254 | 84.1 ± 18.1 |

n defines the number of patients with obtained information in the category. Values are given as numbers and proportions [n (%)] or means with standard deviations (SDs).

ACE, angiotensin‐converting enzyme; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CRT‐D, cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillator; CRT‐P, cardiac resynchronization therapy pacemaker; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; JVP, jugular venous pressure; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA, New York Heart Association; NT‐pro‐BNP, N‐terminal pro‐BNP.

Current or former.

>14/21 units/week.

Non‐insulin‐dependent diabetes mellitus or insulin‐dependent diabetes mellitus.

Percentage FEV1 was abnormally low (<80%) in 55% of the population, and mean %DLCO/VA was reduced (63%). Haemodynamics are presented in Table 1. Patients had signs of increased filling pressures and depressed CO.

Association between haemodynamic variables and lung function parameters

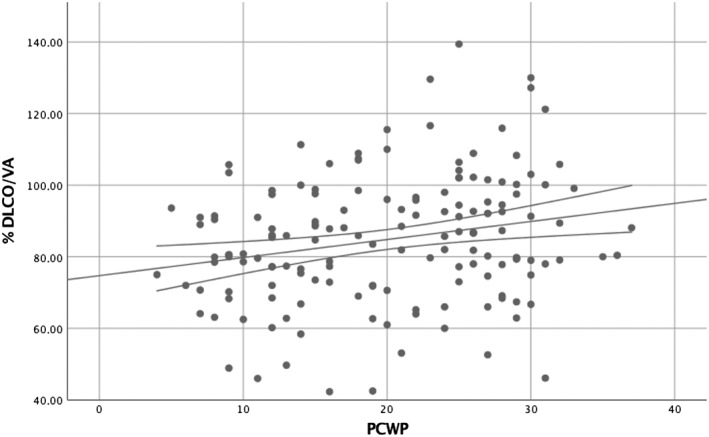

Mean time between PFTs and RHC was 7 days. To test for a potential influence of time elapsed from RHC to pulmonary function testing, sensitivity analyses were performed restricted to the population to those with a maximum of 2 days between the two measurements. Univariate and multivariate linear regression models are shown in Table 2. With the use of univariate analysis, a significant, positive association between %DLCO/VA and PCWP (r 2 = 0.051, P = 0.005) was found (Figure 1 ). Further, %DLCO/VA and MPAP were associated (r 2 = 0.029, P = 0.036). There were no significant associations between %DLCO/VA and CI, MAP, DPG, PVR, or CVP.

Table 2.

Association between %DLCO/VA and haemodynamic variables

| Variables | Total (n = 262) | Within 2 days (n = 156) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P‐value | r 2 | β | P‐value | r 2 | β | |

| Univariate analysis | ||||||

| PCWP | <0.001 | 0.048 | 0.219 | 0.005 | 0.051 | 0.226 |

| CI | NS | NS | ||||

| CVP | NS | NS | ||||

| MAP | NS | NS | ||||

| MPAP | 0.003 | 0.036 | 0.190 | 0.036 | 0.029 | 0.170 |

| DPG | NS | NS | ||||

| PVR | NS | NS | ||||

| Multivariate analysis | ||||||

| 0.139 | 0.18 | |||||

| PCWP | 0.045 | 0.252 | 0.015 | 0.388 | ||

| COPD | 0.047 | −0.122 | 0.034 | −0.165 | ||

| Smokinga | <0.001 | −0.254 | <0.001 | −0.283 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | NS | NS | ||||

| MPAP | NS | NS | ||||

%DCLO/VA, percentage of predicted value of pulmonary diffusion capacity adjusted for alveolar volume; CI, cardiac index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DPG, diastolic pressure gradient; MAP, mean arterial pressure; MPAP, mean pulmonary artery pressure; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance.

Current or former.

Figure 1.

Association between %DLCO/VA and PCWP. PFTs within 2 days of RHC (n = 156). %DCLO/VA, percentage of predicted value of pulmonary diffusion capacity adjusted for alveolar volume; PFTs, pulmonary function tests; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; RHC, right heart catheterization.

When multivariate analyses were performed including the variables PCWP, MPAP, history of smoking, diabetes mellitus, and COPD, PCWP remained significantly associated with %DLCO/VA (P = 0.015).

Analyses were repeated including all 262 patients, and there was still a significant correlation between %DLCO/VA and PCWP in both univariate (r 2 = 0.048, P ≤ 0.001) and multivariate analyses (P = 0.045) with similar coefficients compared with those of the restricted population.

Pulmonary vascular resistance was significantly correlated with %FVC (r 2 = 0.016, P = 0.047) and %FEV1 (r 2 = 0.022, P = 0.018) but not with %DLCO/VA for all patients included.

Smoking and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Active smokers had a reduced %FEV1 (72% vs. 82%), %FVC (79% vs. 84%), and %DLCO/VA (77% vs. 92%) than had non‐smokers. There was also a significant correlation between %DLCO/VA and PCWP in this subpopulation (r 2 = 0.103, P = 0.03). There were no significant changes in our results when patients diagnosed with COPD were excluded from the analysis.

The use of bronchodilators or beta‐blockers was not significantly correlated to any of the lung function parameters.

Lung function parameters, haemodynamics, and outcome

Mean follow‐up time was 3.3 years. At the end of follow‐up, 83 patients (32%) had died and 179 were alive (68%). Out of 262 patients, 37 (14%) received an LVAD and 78 (30%) were transplanted. While 68 (38%) were alive with an LVAD or transplant at follow‐up, 111 (62%) were alive without.

The results of the univariate and multivariate Cox regression models are presented in Table 3. In a univariate analysis, patients in the lower tertiles of %FEV1 and %FVC had a 30% and 40% increased risk of death, LVAD, or transplantation than had those in the highest tertiles (both, P < 0.05). In multivariate Cox models adjusted for age and gender, neither %FEV1 nor %FVC remained significant predictors of the combined endpoint.

Table 3.

Hazard ratios in Cox regression models

| Model 1 (combined endpoint) | Model 2 (combined endpoint) | Model 3 (combined endpoint) | Model 4 (all‐cause mortality) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| %FEV1 | 1.30* (1.10–1.52) | 0.94 (0.67–1.32) | 0.93 (0.65–1.33) | 1.15 (0.69–1.91) |

| %FVC | 1.40* (1.11–1.64) | 1.24 (0.87–1.73) | 1.27 (0.89–1.80) | 1.35 (0.82–2.22) |

| %DLCO/VA | 0.99 (0.81–1.21) | 1.22 (0.97–1.53) | 1.22 (0.97–1.52) | 1.53* (1.11‐2.11) |

| PCWP | 1.03 (0.99–1.07) | 1.03 (1.00–1.08) | 1.03 (0.98–1.07) | |

| CI | 0.64* (0.48–0.86) | 0.60** (0.45–0.81) | 0.59* (0.38‐0.90) | |

| MPAP | 1.01 (0.98–1.05) | 1.01 (0.98–1.04) | 1.03 (0.99–1.07) | |

| CVP | 1.00 (0.97–1.03) | 0.99 (0.97–1.03) | 0.97 (0.92–1.03) | |

| Age | 1.08* (1.02–1.04) | 1.05** (1.05–1.08) | ||

| Gender (male) | 1.09 (0.68–1.73) | 4.50** (1.72–11.77) |

Model 1–3: Data are given as hazard ratio (HR) of combined endpoint of death, heart transplantation, or LVAD implantation with 95% confidence interval. Model 4: Data are given as HR of all‐cause mortality with 95% confidence interval.

Model 1: Univariate models for lung function parameters in tertiles. Model 2: Multivariate model for lung function parameters in tertiles and haemodynamics. Model 3: Multivariate model for lung function parameters in tertiles and haemodynamics adjusted for age and gender. Model 4: Multivariate model for lung function parameters in tertiles and haemodynamics adjusted for age and gender. Hazard ratios are given per 10 units of increase.

%DLCO/VA, percentage of predicted value of pulmonary diffusion capacity adjusted for alveolar volume; %FEV1, percentage of predicted value of forced expiratory volume in 1 s; %FVC, percentage of predicted value of forced vital capacity; CI, cardiac index; CVP, central venous pressure; MPAP, mean pulmonary artery pressure; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure.

P < 0.05.

P < 0.001.

Multivariate Cox analysis identified %DLCO/VA as a predictor of mortality with a 50% increased risk when comparing lower tertiles with highest tertiles (P < 0.05), but it was not a significant predictor of the combined endpoint. Kaplan–Meier survival curves are presented in Figure 2 . There was no statistical significant interaction between PCWP and %DLCO/VA.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Maier curve. Blue = highest tertile of %DLCO/VA. Red = intermediate tertile of %DLCO/VA. Green = lowest tertile of %DLCO/VA. %DCLO/VA, percentage of predicted value of pulmonary diffusion capacity adjusted for alveolar volume.

Discussion

The main findings of the present study are that pulmonary diffusion capacity adjusted for alveolar volume correlated positively, albeit modestly, with left ventricular filling pressures while dynamic lung parameters (%FEV1 and %FVC) did not correlate with haemodynamics in advanced HF. Further, %FEV1 and %FVC predicted adverse outcome, although this association was not apparent after adjustment for confounding factors, whereas diffusion capacity predicted mortality when adjusting for confounders.

Pulmonary diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) is reduced in HF,1, 2, 7, 10, 16, 17 which was also confirmed in the current study when compared with the applied reference material.

Only limited data have been published on the association between central haemodynamics and pulmonary diffusion capacity in CHF. In this study, PCWP was the only haemodynamic variable associated with %DLCO/VA in univariate and multivariate analyses, and, interestingly, there was a positive association between predicted diffusion capacity adjusted for alveolar volume and PCWP. Alteration in DLCO depends on changes in its two components, the alveolar–capillary membrane resistance (DM) and the amount of blood volume available for gas exchange (VC).

The two components modify DLCO in opposite ways, where DM decreases and VC increases DLCO.17, 18 PCWP is an indirect estimate of left atrial pressure and the left ventricular end‐diastolic pressure (LVEDP). Increases in LVEDP are transmitted back to the pulmonary capillaries. As pulmonary congestion usually increases capillary blood volume,1, 18 it could theoretically explain the positive association between PCWP and DLCO/VA. Further studies are of course necessary to verify this hypothesis.

It is well established that lung volume is reduced in HF patients; and the importance of alveolar volume (VA), i.e. the volume of air in the lung available for gas exchange, in interpreting diffusion capacity is, therefore, not without significance. In addition, VA, furthermore, bears a prognostic value because reduced VA is also found to be a significant, independent predictor of mortality in patients with systolic HF.19

Wright et al.7 studied 132 patients with severe chronic CHF referred for HTX and found no association between PCWP and DLCO. Compared with patients in the present study, their population did, in general, have a higher PCWP (26 vs. 20.5 mmHg in the present study) and a slightly higher DLCO (64.5 vs. 62.6%). Also, they did not specify time between RHC and PFTs.

In a study of HF patients, Puri et al.17 reported that a lower DLCO was associated with more severe HF and found that the main component of the impaired diffusion capacity is related to the membrane component (DM). Fluid accumulation is a classic clinical feature in HF, and patients with lung congestion have been shown to display a greater reduction in DLCO.19 A reversible reduction in membrane diffusion capacity can be observed by infusion of saline into CHF patients,20, 21 suggesting that, to some extent, there is a variable component in diffusion capacity seen in CHF, which could be targeted for therapeutic intervention. However, several of studies of patients after HTX have shown that while HTX has a positive effect on total lung capacity, FEV1 and FVC, it does not improve DLCO or DLCO/VA at long‐term follow‐up.22, 23 This suggests that chronic irreversible changes that leads to permanently reduced diffusion capacity despite improved haemodynamics may occur as a consequence of remodelling.

Reduction in diffusion capacity is important in CHF as inability of the alveolar–capillary membrane to maintain an effective gas diffusion contributes to exercise intolerance in CHF.11 However, the importance of DLCO may extend beyond that as studies of both HF patients with reduced ejection fraction12 and preserved ejection fraction24 have reported a significantly worse outcome and higher mortality rate in HF patients with lower diffusion capacity. Olson et al.12 studied 134 HF patients without co‐morbidities that could influence pulmonary function and examined the utility of resting pulmonary function measures in predicting event‐free survival in patients with HF. FEV1 and FVC demonstrated the strongest relationship with event‐free survival, but DLCO and VA were also found to be important prognostic markers. In our study, %DLCO/VA was a significant prognostic predictor of mortality but did not predict the combined endpoint of death, LVAD, or transplantation, while %FEV1 and %FVC were predictors for the combined endpoint in univariate Cox analysis but did not remain significant in multivariate models. One reason for this discrepancy could be differences in patient selection and the endpoints for the study, as fewer patients were transplanted and LVAD implantation was not included in the Olsen study. There is growing evidence suggesting that pulmonary function testing could provide useful additional information in most patients with CHF with or without respiratory co‐morbidities in relation to daily management and as a predictor of mortalily.16, 25

There were no significant changes in our results when patients diagnosed with COPD were excluded from all of our analysis; hence, we decided not to exclude them from the study.

Clinical implication

The heart and lungs are anatomically connected, but our knowledge as to how haemodynamics are related to lung function is sparse. We investigated this relationship and found a positive correlation between diffusion capacity and PCWP, which could be explained by an increase in blood volume available for gas exchange, a consequence of pulmonary congestion. This information is of importance when interpreting PFTs in patients worked up for HTX of LVAD. As we have shown that diffusion capacity is related to mortality, the data should spike further research aimed at clarifying the pathophysiology in lung diffusion capacity in HF and leading to a better understanding of the mechanisms of the lung–heart interactions.

Study limitations

Owing to the limitations of a cross‐sectional study, we cannot conclude on any cause–effect relationship between PCWP and diffusion capacity, and furthermore, because the data collection was limited to one time point, it may not be representative of the entire trajectory of HF patients. In our study population, only 7% of the patients were diagnosed with COPD, which is significantly less than in the general population. This is probably because clinicians are more reluctant to refer patients with (severe) COPD to evaluation for HTX and/or LVAD, and thus, there is most likely selection bias at the referral level.

We investigated a selected HF population with a mean age of 51, which is considerably younger than average HF patients, which may limit the generalizability to the general HF population.

In addition, our study did not allow us to distinguish between the vascular and membrane components of DLCO.

Conclusions

This study explored the association between haemodynamic variables and lung function parameters in patients with CHF. This study is the first to demonstrate a positive association between DLCO/VA and PCWP, possibly explained by an increase in blood volume available for gas exchange, a consequence of pulmonary congestion. DLCO/VA predicted mortality but not the combined endpoint of death, LVAD implantation, and HTX. Further studies allowing for distinction between the vascular and membrane components of DLCO are necessary to explore this association between diffusion capacity and PCWP.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Funding

None declared.

Deis T., Balling L., Rossing K., Wolsk E., Perch M., and Gustafsson F. (2019) Lung diffusion capacity in advanced heart failure: relation to central haemodynamics and outcome, ESC Heart Failure, 6: 379–387. 10.1002/ehf2.12401.

References

- 1. Guazzi M. Alveolar gas diffusion abnormalities in heart failure. J Card Fail 2008; 14: 695–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Siegel JL, Miller A, Brown LK, DeLuca A, Teirstein AS. Pulmonary diffusing capacity in left ventricular dysfunction. Chest 1990; 98: 550–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Griffo R, Spanevello A, Temporelli PL, Faggiano P, Carone M, Magni G, Ambrosino N, Tavazzi L. Frequent coexistence of chronic heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in respiratory and cardiac outpatients: evidence from SUSPIRIUM, a multicentre Italian survey. Eur J Prev Cardiol SAGE PublicationsSage UK: London, England 2017; 24: 567–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hawkins NM, Petrie MC, Jhund PS, Chalmers GW, Dunn FG, McMurray JJ. Heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: diagnostic pitfalls and epidemiology. Eur J Heart Fail 2009; 11: 130–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Canepa M, Temporelli PL, Rossi A, Rossi A, Gonzini L, Nicolosi GL, Staszewsky L, Marchioli R, Pietro MA, Tavazzi L. Prevalence and prognostic impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in patients with chronic heart failure: data from the GISSI‐HF trial. Cardiology 2016; 136: 128–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Olson TP, Beck KC, Johnson BD. Pulmonary function changes associated with cardiomegaly in chronic heart failure. J Card Fail 2007; 13: 100–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wright RS, Levine MS, Bellamy PE, Simmons MS, Batra P, Stevenson LW, Walden JA, Laks H, Tashkin DP. Ventilatory and diffusion abnormalities in potential heart transplant recipients. Chest 1990; 98: 816–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Puri S, Baker BL, Oakley CM, Hughes JM, Cleland JG. Increased alveolar/capillary membrane resistance to gas transfer in patients with chronic heart failure. Br Heart J 1994; 72: 140–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Daganou M, Dimopoulou I, Alivizatos PA, Tzelepis GE. Pulmonary function and respiratory muscle strength in chronic heart failure: comparison between ischaemic and idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Heart 1999; 81: 618–620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Guazzi M. Alveolar–capillary membrane dysfunction in heart failure: evidence of a pathophysiologic role. Chest 2003; 124: 1090–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Faggiano P, D'Aloia A, Gualeni A, Giordano A. Relative contribution of resting haemodynamic profile and lung function to exercise tolerance in male patients with chronic heart failure. Heart 2001; 85: 179–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Olson TP, Denzer DL, Sinnett WL, Wilson T, Johnson BD. Prognostic value of resting pulmonary function in heart failure. Clin Med Insights Circ Respir Pulm Med 2013; 7: 35–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gerges C, Gerges M, Lang MB, Zhang Y, Jakowitsch J, Probst P, Maurer G, Lang IM. Diastolic pulmonary vascular pressure gradient: a predictor of prognosis in ‘out‐of‐proportion’ pulmonary hypertension. Chest 2013; 143: 758–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Quanjer PH, Tammeling GJ, Cotes JE, Pedersen OF , Peslin R, Yernault JC. Lung volumes and forced ventilatory flows. Eur Respir J Eur Res Soc 1993; 6: 5–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cotes JE, Chinn DJ, Quanjer PH, Roca J, Yernault JC. Standardization of the measurement of transfer factor (diffusing capacity). Report Working Party Standardization of Lung Function Tests, European Community for Steel and Coal. Official Statement of the European Respiratory Society. Eur Respir J Suppl 1993; 16: 41–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Magnussen H, Canepa M, Zambito PE, Brusasco V, Meinertz T, Rosenkranz S. What can we learn from pulmonary function testing in heart failure? Eur J Heart Fail 2017; 19: 1222–1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Puri S, Baker BL, Dutka DP, Oakley CM, Hughes JM, Cleland JG. Reduced alveolar–capillary membrane diffusing capacity in chronic heart failure. Its pathophysiological relevance and relationship to exercise performance. Circulation 1995; 91: 2769–2774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Assayag P, Benamer H, Aubry P, De PC, Brochet E, Besse S, Camus F. Alteration of the alveolar–capillary membrane diffusing capacity in chronic left heart disease. Am J Cardiol 1998; 82: 459–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Miniati M, Monti S, Bottai M, Pavlickova I, Passino C, Emdin M, Poletti R. Prognostic value of alveolar volume in systolic heart failure: a prospective observational study. BMC Pulm Med 2013; 13: 69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Guazzi M, Agostoni P, Bussotti M, Guazzi MD. Impeded alveolar–capillary gas transfer with saline infusion in heart failure. Hypertension 1999; 34: 1202–1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Puri S, Dutka DP, Baker BL, Hughes JM, Cleland JG. Acute saline infusion reduces alveolar–capillary membrane conductance and increases airflow obstruction in patients with left ventricular dysfunction. Circulation 1999; 99: 1190–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mettauer B, Lampert E, Charloux A, Zhao QM, Epailly E, Oswald M, Frans A, Piquard F, Lonsdorfer J. Lung membrane diffusing capacity, heart failure, and heart transplantation. Am J Cardiol 1999; 83: 62–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ravenscraft SA, Gross CR, Kubo SH, Olivari MT, Shumway SJ, Bolman RM, Hertz MI. Pulmonary function after successful heart transplantation; one year follow‐up. Chest 1993; 103: 54–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hoeper MM, Meyer K, Rademacher J, Fuge J, Welte T, Olsson KM. Diffusion capacity and mortality in patients with pulmonary hypertension due to heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. JACC Hear Fail 2016; 4: 441–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Huang W, Resch S, Oliveira RK, Cockrill BA, Systrom DM, Waxman AB. Invasive cardiopulmonary exercise testing in the evaluation of unexplained dyspnea: insights from a multidisciplinary dyspnea center. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2017; 24: 1190–1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]