Candida albicans, the causative agent of mucosal infections, including oropharyngeal candidiasis (OPC), as well as bloodstream infections, is becoming increasingly resistant to existing treatment options. In the absence of novel drug candidates, drug repurposing aimed at using existing drugs to treat off-label diseases is a promising strategy.

KEYWORDS: Candida albicans, deferasirox, drug repurposing, iron, iron chelation, neutrophils, oral epithelial cells, oropharyngeal candidiasis, saliva

ABSTRACT

Candida albicans, the causative agent of mucosal infections, including oropharyngeal candidiasis (OPC), as well as bloodstream infections, is becoming increasingly resistant to existing treatment options. In the absence of novel drug candidates, drug repurposing aimed at using existing drugs to treat off-label diseases is a promising strategy. C. albicans requires environmental iron for survival and virulence, while host nutritional immunity deploys iron-binding proteins to sequester iron and reduce fungal growth. Here we evaluated the role of iron limitation using deferasirox (an FDA-approved iron chelator for the treatment of patients with iron overload) during murine OPC and assessed deferasirox-treated C. albicans for its interaction with human oral epithelial (OE) cells, neutrophils, and antimicrobial peptides. Therapeutic deferasirox treatment significantly reduced salivary iron levels, while a nonsignificant reduction in the fungal burden was observed. Preventive treatment that allowed for two additional days of drug administration in our murine model resulted in a significant reduction in the number of C. albicans CFU per gram of tongue tissue, a significant reduction in salivary iron levels, and significantly reduced neutrophil-mediated inflammation. C. albicans cells harvested from the tongues of animals undergoing preventive treatment had the differential expression of 106 genes, including those involved in iron metabolism, adhesion, and the response to host innate immunity. Moreover, deferasirox-treated C. albicans cells had a 2-fold reduction in survival in neutrophil phagosomes (with greater susceptibility to oxidative stress) and reduced adhesion to and invasion of OE cells in vitro. Thus, deferasirox treatment has the potential to alleviate OPC by affecting C. albicans gene expression and reducing virulence.

INTRODUCTION

The yeast Candida albicans is the most abundant member of the oral fungal community, or the mycobiome (1). C. albicans can cause oropharyngeal candidiasis (OPC) when host immune responses are diminished or denture stomatitis among denture wearers. Furthermore, in the United States alone, Candida species have been observed to be the fourth leading cause of nosocomial bloodstream infections, which often result in high mortality rates (reviewed in reference 2). The oral cavity has now been shown to be a potential source of C. albicans for such infections (3, 4). Currently, only three major classes of clinical antifungal drugs exist (5); unfortunately, there has been a steady increment in the incidence of fungal drug resistance (reviewed in reference 6), while no new class of antifungals has emerged in decades (5).

Oral microorganisms depend largely on saliva as a source of carbon and nitrogen, as well as essential trace elements, including metals, for their survival. Iron is one of the most essential metals required by all living organism for growth. In all living organisms, including C. albicans, iron is essential for many cellular processes, such as energy production and DNA repair. Iron participates in oxidation-reduction reactions, is a part of heme- and FeS cluster-containing proteins, and is a cofactor for various other proteins. Besides its role in primary cellular functions, iron also modulates the C. albicans transcriptome (7, 8); the chromatome, or the state of the chromatin in terms of accessibility to the DNA replication machinery (9); and signals into Cek1 (9) and Hog1 (10) mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways to alter virulence traits, such as adhesion, biofilm formation, and germination. A mutant of C. albicans lacking a high-affinity iron permease transporter, FTR1, is avirulent in systemic infection (11).

Nutritional immunity, whereby the host sequesters essential micronutrients from invading pathogens, is one component of innate immunity. Saliva contains various metal-binding proteins dedicated to this purpose. Salivary lactoferrin (LF) is an iron-binding glycoprotein that has antifungal activity, and its importance is highlighted by the fact that LF-deficient mice showed a 2-fold higher fungal burden of oral C. albicans than wild-type mice, while administration of human LF to these mice resulted in significantly reduced C. albicans levels (12). Furthermore, intracellular metal sequestration, particularly the sequestration of iron, has been proposed to be one of the antifungal mechanisms for salivary Histatin 5 (Hst 5), since Hst 5 can bind up to 10 equivalents of iron and iron uptake genes are downregulated in Hst 5-treated cells (13).

The importance of iron is further underscored by the fact that C. albicans has multiple pathways dedicated to iron acquisition. These include reductive iron uptake, heme iron acquisition, and siderophore-mediated uptake pathways (reviewed in reference 14), and cells deploy intricate mechanisms utilizing multiple transcriptional regulators (TRs) that allow them to adapt to host niches differing in iron bioavailability (7). Iron is more bioavailable at acidic pH, while the resting pH (6.6 to 6.9) of saliva in a healthy mouth is near neutral, adding an additional layer of sequestration. However, acid produced by oral bacteria can decrease the pH of the saliva (15), thereby increasing iron availability. Iron is the second most abundant metal in saliva (16), and it has been proposed that 30% of total salivary iron is soluble (17). Also, unlike human intestinal cells, which express a divalent metal transporter (reviewed in reference 18), there are no known mechanisms for iron absorption for oral mucosa. Together, these present possible pools of bioavailable oral iron, despite the host’s attempt at sequestration, that can be used by C. albicans.

Studies linking virulence with bioavailable iron are limited. However, Candida spp. were responsible for 68% of invasive fungal infections recorded in a cohort having a positive correlation with hepatic iron overload (19). Exacerbations of Candida spp. infections have also been reported in iron-overloaded thalassemia patients in Europe (20). Deferasirox, an FDA-approved iron chelator for patients with iron overload, showed promising antifungal effects against fungal mucormycosis in animal models (21) as well as synergy with antifungals against Cryptococcus neoformans in vitro (22). More recently, another iron chelator (DIBI) was shown to eliminate vaginal candidiasis when administered along with fluconazole in a mouse model (23).

Very little is known about the effect of metals on C. albicans growth in the oral cavity, although oral carriage of yeast has been shown to correlate with salivary metal levels (16). Given the importance of iron in C. albicans virulence, deferasirox treatment may help alleviate OPC or may be indicated for preventive/prophylactic treatment of high-risk immunosuppressed populations. Here we show that deferasirox treatment can help reduce the C. albicans tissue burden in a murine model of OPC, with concomitant changes in the expression of fungal genes involved in iron metabolism and adhesion. Furthermore, we show that treatment causes a reduction in fungal survival in phagosomes and lowers the levels of C. albicans adhesion to and invasion of oral epithelial cells.

RESULTS

Deferasirox treatment reduced the severity of murine OPC and the fungal burden in tongue tissues.

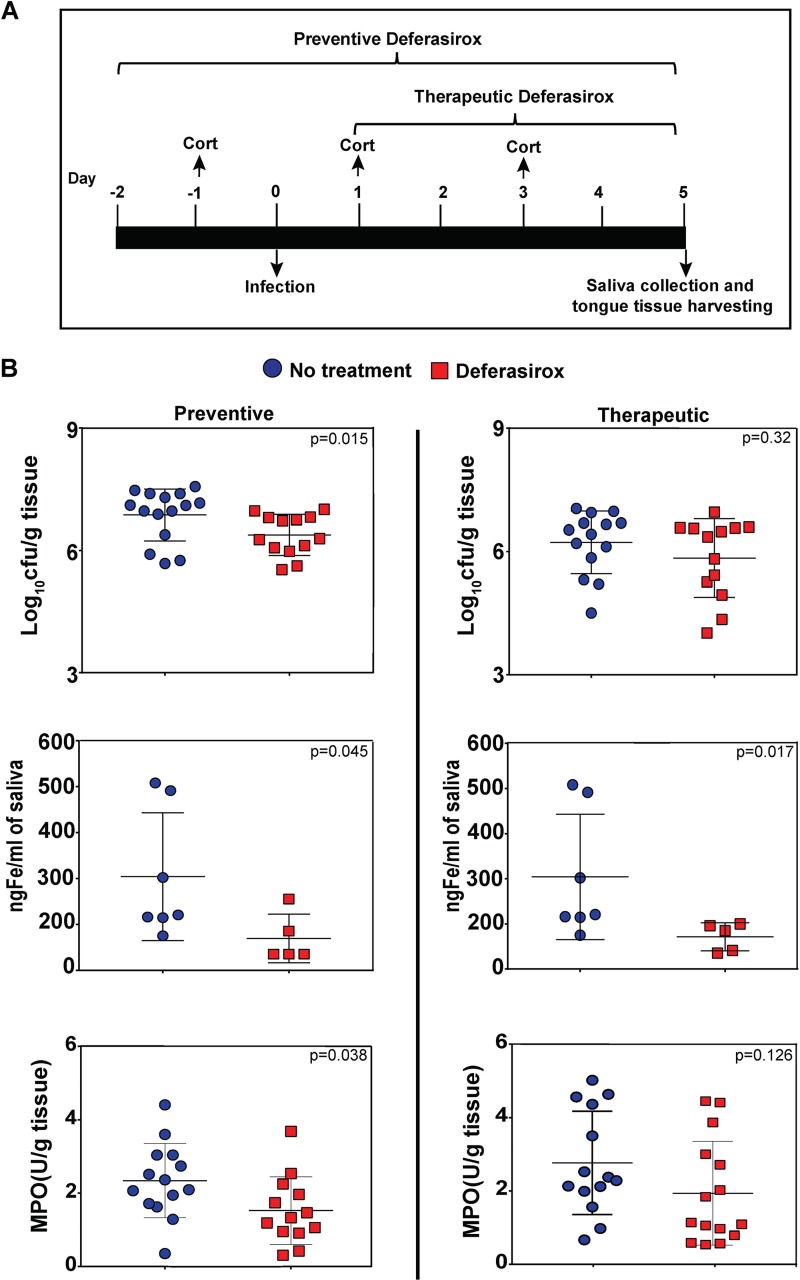

We hypothesized that oral administration of deferasirox to mice in drinking water would lower the iron levels in saliva and thus reduce the availability of the environmental iron needed to sustain C. albicans infection. We therefore tested a therapeutic regimen whereby deferasirox was administered from days 1 through 5, subsequent to infection with C. albicans (using an immunosuppressed mouse model where mice are infected with fungal cells orally and sublingually on day 0 and given immunosuppressive cortisone injections on days −1, +1, and +3; Fig. 1A). Therapeutic treatment reduced the fungal burden in tongue tissue (6.2 ± 0.8 log10 CFU/g for untreated mice to 5.4 ± 1.4 log10 CFU/g for treated mice), although the levels of reduction were not statistically significant (Fig. 1B, top). Next, we used a preventive regimen (deferasirox administered starting 2 days prior to infection and over the 5-day course of infection) (Fig. 1A). Preventive deferasirox treatment significantly reduced the fungal burden in tongue tissue compared to that in untreated mice (mean, 6.9 ± 0.6 log10 CFU/g for control mice and 6.38 ± 0.5 log10 CFU/g for treated mice) (P = 0.015, Mann-Whitney U test) (Fig. 1B, top). Both the preventively and therapeutically treated groups of mice had a significant 4-fold reduction in salivary iron levels compared to those in the respective control groups (P = 0.045 and P = 0.017, respectively, Mann-Whitney U test) (Fig. 1B, middle). To examine the extent of neutrophil invasion as a marker of inflammation induced by fungal infection, tongue myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity was also measured. Tongues from mice receiving preventive deferasirox treatment had significantly reduced MPO activity (almost 2-fold) in tongue tissue homogenates than tongues from untreated mice (P = 0.038, two-tailed t test), while the mean MPO activity was reduced, but not significantly, in tongue tissues from mice receiving therapeutic deferasirox treatment (P = 0.126) (Fig. 1B, bottom). Thus, although both treatment regimens resulted in reduced salivary iron levels, the longer duration of preventive therapy was more effective in reducing the number of tongue C. albicans CFU and neutrophil-mediated inflammation.

FIG 1.

Deferasirox treatment reduced the fungal burden in tongue tissue. (A) Timeline of oral candidiasis infection in mice. Immunosuppression with cortisone (Cort), infection with C. albicans, and preventive and therapeutic treatment with deferasirox. (B) (Top) The numbers of CFU per gram of tongue tissues were obtained from C. albicans-infected mice. Preventive deferasirox treatment significantly reduced the number of tongue CFU compared to that in the no-treatment group (P = 0.015, Mann-Whitney U test). Therapeutic treatment also reduced the tongue fungal burden without significance (P = 0.32). (Middle) Mice treated with deferasirox, both preventively and therapeutically, had a significant (P = 0.045 and P = 0.017, respectively) reduction in the salivary iron concentration (in nanograms per milliliter) compared to that in the no-treatment group. (Bottom) Preventive deferasirox significantly reduced the tongue myeloperoxidase (MPO) level (units per gram of tissue) compared to that in the no-treatment group (P = 0.038, t test), while therapeutic treatment reduced the MPO level without significance (P = 0.126). Data were pooled from two independent experiments for numbers of CFU and MPO levels. Bars show the mean ± SD.

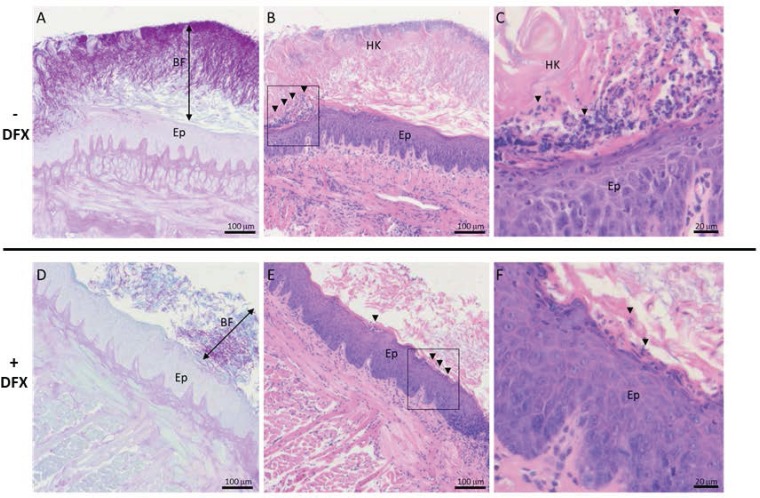

To validate C. albicans infection histologically, sagittal tongue tissue sections of the entire tongue surface of preventively treated and control mice were stained with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), to evaluate C. albicans infection, epithelial structure, and inflammatory cell infiltration. Tongues from untreated mice had a thick, well-organized biofilm (BF) of C. albicans yeasts and hyphae located at the corneum stratum of the tongue epithelium, above the granulosum stratum (Fig. 2A). Marked hyperkeratosis (HK) of the filiform papillae and areas of inflammatory cell infiltration characteristic of neutrophils with a multilobed nucleus were also observed (Fig. 2B and C, arrowheads). In deferasirox-treated mice, the C. albicans BF was thinner and less organized (Fig. 2D), and the tongue epithelium had less hyperkeratosis and reduced inflammatory cell infiltration (Fig. 2E and F). No invasion of lower epithelial layers or underlying connective tissue was observed within the tongues from either group of mice. Thus, histology qualitatively corroborated that the severity of infection was reduced in deferasirox-treated mice.

FIG 2.

Deferasirox (DFX) treatment reduced the severity of fungal infection and inflammation in tongue tissue. Representative photomicrographs of sagittal tongue tissue sections of untreated (A, B, C) and preventive deferasirox-treated (D, E, F) mice are shown. Tissue sections (4 μm thick) were processed for PAS staining (A, D) or H&E staining (B, C, E, F). Arrows indicate the C. albicans biofilm thickness (A, D). Arrowheads indicate areas of inflammatory infiltrate (B, E) and neutrophils (C, F). The boxed regions in panels B and E are enlarged in panels C and F, respectively. HK, hyperkeratosis; Ep, epithelium; BF, biofilm. Bars, 100 μm (A, B, D, E) or 20 μm (C, F).

Deferasirox therapy altered C. albicans gene expression during OPC.

The gene expression of C. albicans cells harvested from the tongues of untreated mice was compared with that of C. albicans cells harvested from the tongues of mice administered preventive deferasirox treatment using RNA sequencing (RNA-seq). Using a Log2 fold change in expression and a P value of ≤0.05 as the threshold for significance, 106 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Based on gene descriptions in the Candida Genome Database (CGD) (24), 25 genes (Table 1) out of the 106 DEGs either were regulated by transcriptional factors (Hap43, Sfu1, Sef1, and Tup1) involved in the regulation of iron metabolism (7, 25), were directly regulated by iron (ALS2 and PGA48) (8), or had iron-related functions (PGA10 and ARH2, required for heme iron acquisition [26] and heme biosynthesis [27], respectively).

TABLE 1.

C. albicans genes that have iron-mediated regulation/iron-related functions or that are involved in adhesion/cell wall-related functions and the response to host innate immunity that are differentially expressed after preventive deferasirox treatment

| Gene group and gene identifier | Gene name | Functiona | Log2 fold change in expression | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upregulated C. albicans genes with iron-mediated regulation or iron-related functions | ||||

| C1_04660W_B | DUR1, DUR2 | Use of urea as N source and for hyphal switch in macrophage; regulated by Nrg1/Hap43 | 4.08792 | 0.00005 |

| CR_01910C_B | BIO4 | Putative dethiobiotin synthetase; transcript upregulated in clinical isolates from HIV-positive patients with oral candidiasis; Hap43 repressed | 3.17951 | 0.00905 |

| CR_04210C_A | QDR1 | Regulated by white-opaque switch, Nrg1, and Tup1; Hap43 repressed | 3.1071 | 0.00015 |

| CR_03270W_A | VHT1 | Predicted membrane transporter; member of the ACS family and MFS; Hap43p repressed | 3.00409 | 0.00105 |

| C1_08790W_B | TPO3 | Putative polyamine transporter; member of the MFS-MDR family; induced by Sfu1; decreased expression in hyphae vs yeast-form cells; regulated by Nrg1 | 2.33814 | 0.0124 |

| C4_00450C_B | PGA10 | GPI-anchored membrane protein; utilization of hemin and hemoglobin for Fe in host | 2.10848 | 0.00345 |

| C2_08590W_A | YWP1 | Secreted yeast wall protein; possible role in dispersal in host; mutation increases adhesion and biofilm formation; propeptide; growth phase, phosphate, and Ssk1/Ssn6/Efg1/Efh1/Hap43 regulated | 2.10571 | 0.0054 |

| C6_01510W_B | OYE23 | Putative NAPDH dehydrogenase; induced by nitric oxide and benomyl; oxidative stress induced via Cap1; Hap43p repressed | 2.03668 | 0.0264 |

| C6_04380W_A | ALS2 | ALS family protein; role in adhesion, biofilm formation, and germ tube induction; expressed at infection of human buccal epithelial cells; induced by low iron; regulated by Sfu1p | 1.64312 | 0.00265 |

| C2_08260W_B | NA | Protein of unknown function; Hap43 repressed gene | 1.48262 | 0.0305 |

| C2_04880C_A | ARH2 | Putative adrenodoxin-NADPH oxidoreductase; role in heme biosynthesis | 1.1585 | 0.04425 |

| Downregulated C. albicans genes with iron-mediated regulation or iron-related functions | ||||

| C6_03790C_B | HGT10 | Glycerol permease involved in glycerol uptake; member of the major facilitator superfamily; Hap43p induced gene | −2.50627 | 0.0251 |

| C6_02100W_A | LDG8 | Secreted protein; Hap43 repressed; fluconazole induced; regulated by Tsa1 and Tsa1B under H2O2 stress conditions; induced by Mnl1p under weak acid stress | −2.35105 | 0.00025 |

| C4_06390W_A | SOU1 | Enzyme involved in utilization of l-sorbose; has sorbitol dehydrogenase, fructose reductase, and sorbose reductase activities; Hap43p induced gene | −2.06913 | 0.0017 |

| CR_04960C_A | CRG1 | Methyltransferase involved in sphingolipid homeostasis; decreased expression in hyphae compared to yeast; expression regulated during planktonic growth; flow model biofilm induced; Hap43 repressed gene | −1.72716 | 0.01065 |

| C3_04080W_B | NA | Ortholog of subunit 6 of the ubiquinol cytochrome c reductase complex; a component of the mitochondrial inner membrane electron transport chain; Hap43 repressed gene | −1.71289 | 0.0135 |

| C4_01100C_B | AGP2 | Amino acid permease; regulated by Sef1, Sfu1, and Hap43 | −1.53575 | 0.00275 |

| CR_04820W_B | NA | Protein of unknown function; Hap43 induced | −1.51326 | 0.0055 |

| C3_00930W_A | ATO2 | Putative fungus-specific transmembrane protein; fluconazole repressed; Hap43 repressed | −1.50839 | 0.012 |

| C2_07630C_A | NA | Possible stress protein; increased transcription associated with CDR1 and CDR2 overexpression or fluphenazine treatment; regulated by Sfu1, Nrg1, and Tup1 | −1.33091 | 0.0089 |

| C1_09150W_B | AOX2 | Alternative oxidase; cyanide-resistant respiration; induced by antimycin A and oxidants; Hap43 repressed | −1.30376 | 0.043 |

| C1_10740C_B | ASR1 | Heat shock protein; repressed by Cyr1 and Ras1; Hap43 induced | −1.25044 | 0.01335 |

| C1_11850W_A | NA | Protein of unknown function; Hap43-repressed gene; induced by Mnl1 under weak acid stress | −1.1733 | 0.04345 |

| C6_02500C_B | GCV1 | Putative T subunit of glycine decarboxylase; transcript negatively regulated by Sfu1 | −1.05165 | 0.03175 |

| C6_00160W_B | PGA48 | Putative GPI-anchored adhesin-like protein; transcript induced in high iron; flow model biofilm induced | −1.00213 | 0.0477 |

| Upregulated C. albicans adhesion or cell wall-related genes | ||||

| C2_08590W_A | YWP1 | Secreted yeast wall protein; possible role in dispersal in host; mutation increases adhesion and biofilm formation; propeptide; growth phase, phosphate, and Ssk1/Ssn6/Efg1/Efh1/Hap43 regulated; mRNA binds She3; flow and Spider biofilm repressed | 2.10571 | 0.0054 |

| C6_04380W_A | ALS2 | Ind by low Fe; ALS family protein; role in adhesion, biofilm formation, and germ tube induction; expressed at infection of human buccal epithelial cells; putative GPI anchor; induced by ketoconazole, by low iron, and at cell wall regeneration; regulated by Sfu1p | 1.64312 | 0.00265 |

| C6_04130C_B | ALS4 | GPI-anchored adhesin; role in adhesion and germ tube induction; growth and temperature regulated; expressed during infection of human buccal epithelial cells; repressed by vaginal contact; biofilm induced; repressed during chlamydospore formation | 1.37573 | 0.0279 |

| Downregulated C. albicans adhesion or cell wall-related genes | ||||

| C4_04080C_B | PGA31 | Cell wall protein; putative GPI anchor; expression regulated upon white-opaque switch; induced by Congo red and cell wall regeneration; Bcr1-repressed in RPMI a/a biofilms | −4.18385 | 0.00425 |

| C1_10430W_B | PHO8 | Putative repressible vacuolar alkaline phosphatase; Rim101-induced transcript; regulated by Tsa1 and Tsa1B in minimal medium at 37°C; possibly adherence induced | −1.96872 | 0.02755 |

| CR_04420C_B | RBR2 | Cell wall protein; expression repressed by Rim101; transcript regulated upon white-opaque switching; repressed by alpha pheromone in SpiderM medium; macrophage-induced gene | −1.84517 | 0.02255 |

| C4_01940W_B | PHO89 | Putative phosphate permease; transcript regulated upon white-opaque switch; alkaline induced by Rim101; possibly adherence induced; F-12 medium–CO2 model, rat catheter, and Spider biofilm induced | −1.38298 | 0.0348 |

| C6_00160W_A | PGA48 | Putative GPI-anchored adhesin-like protein; similar to Saccharomyces cerevisiae Spi1p, which is induced at stationary phase; transcript induced in high iron; flow model biofilm induced; Spider biofilm repressed | −1.21915 | 0.02295 |

| Downregulated C. albicans genes that mediate response to host innate immunity | ||||

| CR_06460W_B | GST3 | Glutathione S-transferase; expression regulated upon white-opaque switch; induced by human neutrophils; peroxide induced; induced by alpha pheromone in SpiderM medium; Spider biofilm induced | −2.29826 | 0.0287 |

| C2_00680C_A | SOD5 | Cu-containing superoxide dismutase; protects against oxidative stress; induced by neutrophils, hyphal growth, caspofungin, and osmotic/oxidative stress; oropharyngeal candidiasis induced; rat catheter and Spider biofilm induced | −1.38752 | 0.02145 |

| C1_04300C_B | SSA2 | HSP70 family chaperone; cell wall fractions; antigenic; beta-defensin peptide import; ATPase domain binds histatin 5; at hyphal surface but not yeast surface; farnesol repressed in biofilm; flow model and Spider biofilm repressed; caspofungin repressed | −1.2119 | 0.0199 |

NA, not available; ACS, anion:cation symporter family; MFS, major facilitator superfamily. Boldface indicates pertinent key terms.

C. albicans genes involved in adhesion as well as genes encoding cell wall proteins were also affected by deferasirox treatment (Table 1). While adhesins encoded by ALS2 and ALS4 were upregulated, the expression of other genes with opposing effects was observed, including the upregulation of YWP1, which has a role in dispersal, and the downregulation of PGA48 (a putative glycosylphosphatidylinositol [GPI]-anchored adhesin-like protein), as well as PHO8 and PHO89 (potentially adherence-induced proteins). We further identified other C. albicans genes (the SOD5 and GST3 genes and the SSA2 gene) that affect its interaction with the oral innate immune response (neutrophil and Hst 5-mediated killing, respectively) that were downregulated upon deferasirox treatment (Table 1).

Deferasirox-treated C. albicans cells have reduced survival in phagosomes and reduced adhesion to and invasion of oral epithelial cells.

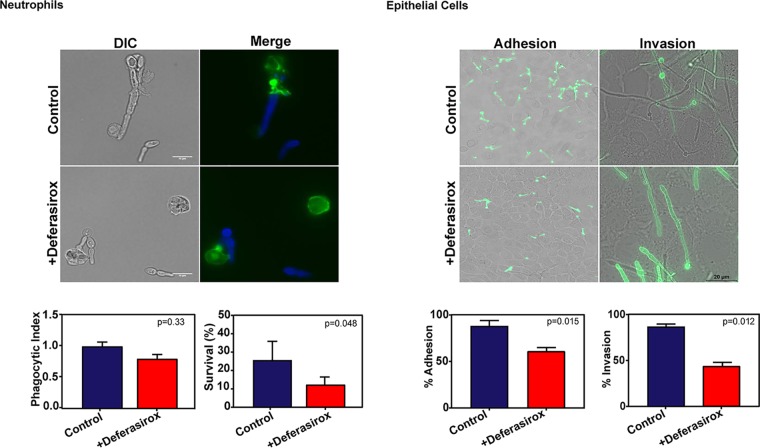

To determine the reason for reduced infection (Fig. 1) and inflammation (Fig. 2) upon deferasirox treatment, we compared deferasirox-treated cells with untreated C. albicans cells for differences in neutrophil uptake (phagocytosis) and subsequent survival within the phagosome. The phagocytosis of fungal cells by primary human neutrophils was evaluated using a phagocytic index (PI) and immune-fluorescent staining (Fig. 3, top left). Fungal cells showed a normal cell morphology and hyphal formation after exposure to deferasirox (Fig. 3, top left) and were as efficiently phagocytized by human neutrophils as untreated cells (PI = 0.80 and 1.0, respectively; P = 0.33, unpaired Student's t test) (Fig. 3, bottom left). However, phagocytosed deferasirox-treated C. albicans cells showed a significant decrease in survival (12.2%) compared to untreated control fungal cells (25.2%) (P = 0.048) (Fig. 3, bottom left), suggesting that they are more susceptible to oxidative and/or nonoxidative killing.

FIG 3.

Deferasirox-treated C. albicans cells have reduced survival in phagosomes and reduced adhesion to and invasion of oral epithelial cells. (Left) (Top) Deferasirox-treated C. albicans cells are phagocytosed by human neutrophils similarly to untreated control yeast cells. DIC, differential inference contrast. (Bottom) Human neutrophils were infected with C. albicans deferasirox-treated or untreated cells, and the phagocytic index was calculated after 30 min (left). The survival of C. albicans within human neutrophils was evaluated after 3 h by plating lysed neutrophils to measure the numbers of yeast CFU (right). Deferasirox-treated C. albicans cells showed a normal hyphal morphology and had no difference in the phagocytic index from untreated cells but had significantly (P = 0.048) reduced survival within neutrophils compared to untreated cells. (Right) (Top) Deferasirox-treated C. albicans cells were quantitated for adhesion to (1.5 h) and invasion of (4.5 h) TR146 epithelial cell monolayers grown on glass coverslips. For adhesion quantitation, nonadherent C. albicans cells were removed by washing, and adherent Candida cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde. For invasion quantitation, adherent Candida cells (after 4.5 h) were stained with anti-Candida antibody and Alexa Fluor 488. (Bottom) Quantification of adherent cells showed that C. albicans cells treated with deferasirox had significantly reduced adhesion to (P = 0.015; left) and invasion of (P = 0.012; right) TR146 epithelial cell monolayers compared with control cells. Results represent the mean ± standard deviation from three independent experiments.

Since most of the tissue destruction during C. albicans epithelial infections is a result of the invasion of host tissue by fungal hyphae, we also examined the effect of deferasirox on the ability of C. albicans to adhere to and invade oral epithelial (OE) cells. Adhesion and invasion were observed microscopically (Fig. 3, top right). Alexa Flour 488-stained C. albicans cells (with green fluorescence) with and without small germ tubes were observed over confluent OE cells after 2 h, while after 5 h of coincubation, some hyphae were observed to invade OE cells (as shown by the loss of the green fluorescence; Fig. 3, top right). Quantification of adherent cells showed that C. albicans cells treated with deferasirox had significantly reduced adhesion to (P = 0.015) and invasion of (P = 0.012) OE cells compared with untreated cells (Fig. 3, bottom right). Together, these data suggest that deferasirox treatment not only makes fungal cells more susceptible to neutrophil killing but also reduces their ability to adhere to and invade OE cells.

Deferasirox-treated C. albicans cells have altered responses to hydrogen peroxide and Hst 5.

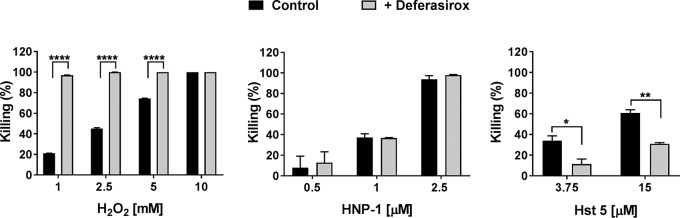

To understand the reason for the reduced survival of deferasirox-treated C. albicans cells inside the neutrophil phagosome (Fig. 3), we examined the susceptibility of deferasirox-treated C. albicans cells to oxidative and nonoxidative neutrophil-mediated killing mechanisms in vitro. When deferasirox-treated C. albicans cells were further treated with H2O2, they showed significantly increased susceptibility to oxidative stress, with nearly 100% killing being seen in cells treated with 1 mM H2O2 but 20% killing being seen in control cells not treated with peroxide (P < 0.001) (Fig. 4, left). In contrast, no differences in the susceptibility of deferasirox-treated C. albicans cells to the cytotoxic human neutrophil peptide 1 (HNP-1) (Fig. 4, middle) were found, suggesting that deferasirox treatment increased C. albicans susceptibility to oxidative stress but not to nonoxidative stress following phagocytosis by neutrophils.

FIG 4.

Deferasirox-treated C. albicans cells have increased susceptibility to hydrogen peroxide but less sensitivity to Hst 5. C. albicans control and deferasirox-treated cells were incubated with 1, 2.5, 5, or 10 mM H2O2 for 2 h at 30°C (left), 0.5, 1, or 2.5 μM human neutrophil peptide 1 (HNP-1) for 1 h at 37°C (middle), and 3.75 and 15 μM histatin 5 (Hst 5) for 1 h at 30°C (right). Cells were then diluted and plated on agar to obtain the number of viable CFU. Killing was calculated as 1 – (number of CFU from treated plates/number of CFU from control plates). Results represent the mean ± standard deviation from two independent experiments. Significance was calculated using Student's t test.

As a part of human salivary innate immunity, Hst 5 also plays an important candidacidal function. Since we found decreased expression of C. albicans SSA2 (the cell surface protein required for Hst 5 binding) (Table 1) following deferasirox treatment, we expected that cells might have altered susceptibility to Hst 5. Indeed, deferasirox-treated fungal cells were significantly less susceptible to 3.75 and 15 μM Hst 5 (P = 0.0415 and P = 0.006, respectively; Fig. 4, right). Thus, deferasirox may render C. albicans less susceptible to Hst 5 by reducing its uptake by the fungal cells.

DISCUSSION

Here we present the first study on the effect of iron chelation as a treatment modality for OPC. Preventive deferasirox administration resulted in decreased salivary iron levels, which correlated with a significant reduction in the fungal load in tongue tissue (Fig. 1). While the reduction in C. albicans levels in the therapeutic arm of the study was comparable to that in the preventive arm, it did not reach statistical significance. This is likely a result of the inherent limitation of this OPC model, whereby decreased water intake by mice as the oral infection progresses can reduce the amount of drug administered; this limitation was potentially overcome in the preventive arm, due to the addition of two extra days of infection-free drug administration. Alternative drug delivery methods are very likely to improve the significance in the therapeutic arm as well. These data also suggest that oral rinses in clinical trials with humans might prove highly effective for the treatment of OPC, since fungal growth in the presence of deferasirox for only 2 to 3 h resulted in reduced adhesion to and invasion of oral epithelial cells. However, this study was conducted using only one genetically marked strain, and therefore, further testing of wild-type clinical isolates may be warranted.

Changes in the C. albicans transcriptome (7, 8) and chromatome (9) in response to environmental iron have been studied extensively in vitro. However, this study provides the first transcriptome of C. albicans as a function of host iron levels during infection in vivo. Regulation of iron in C. albicans is mediated primarily by four transcriptional regulators (TRs), Tup1 (a global repressor) (25), Hap43 (a repressor/activator), Sfu1 (a repressor), and Sef1 (an activator) (7), that allow it to moderate intracellular iron levels. Cells lacking Sfu1 or Sef1 have altered fitness in niches with various iron levels, such as the iron-rich gut and low-iron blood (7). Deferasirox-treated mice showed alterations in 22 genes regulated by one or more of these TRs (Table 1), showing that C. albicans responds to perturbations in host iron levels in real time during infection.

Adherence to epithelial cells followed by their invasion is an important attribute of C. albicans virulence. Large cell surface glycoproteins encoded by the agglutinin-like sequence (ALS) gene family are major cell surface adhesins that play an important role in attachment to epithelium surfaces (28). Previous microarray data have shown that the levels of ALS2 and ALS4 transcripts are upregulated under low-iron conditions (8). Our RNA-seq data also showed that the C. albicans ALS2 and ALS4 genes are upregulated in deferasirox-treated mice (Table 1). Surprisingly, we did not observe any change in the expression of another important adhesin gene (ALS3) in our RNA-seq analysis, despite its role in iron acquisition from ferritin (29). However, studies showing the upregulation of ALS3 were conducted either in mice without any chelator treatment (30) or ex vivo with OE cells (29), and it is important to note that a compensatory function within the ALS family has been proposed (31). We did, however, observe the upregulation of the YWP1 gene and the downregulation of the PGA48, PHO8, and PHO89 genes (Table 1). Since a mutation in YWP1 increases adhesion (32), increases in its expression, along with the decrease in potential adhesin-like protein (Pga48) and, possibly, adherence-induced proteins (Pho8 and Pho89), may reduce C. albicans adhesion to OE cells, explaining the reduction in the fungal burden in vivo (Fig. 1) and the reduced adherence of deferasirox-treated C. albicans to OE cells in vitro (Fig. 3).

The iron-mediated differential expression of additional novel genes was identified in this study, and this finding further supports the role of iron chelation as a potential treatment strategy against OPC. We observed a reduction in the expression of C. albicans genes encoding SOD5 (encoding a primary C. albicans superoxide dismutase enzyme responsible for protecting fungal cells from neutrophil-mediated oxidative stress [33]) and GST3 (encoding a C. albicans enzyme involved in resistance to peroxide stress) (Table 1) in deferasirox-treated mice. Downregulation of these two genes may explain the greater susceptibility of deferasirox-treated C. albicans cells to H2O2 (Fig. 4), which potentially led to reduced survival in neutrophil phagosomes (Fig. 3). The iron-mediated downregulation of C. albicans SSA2 (Table 1), on the other hand, may reduce the cell wall binding of Hst 5, resulting in resistance to killing (Fig. 4). Metabolic inhibition due to the slowing down of active respiration has been shown to reduce Hst 5 susceptibility in C. albicans (reviewed in reference 34). Hence, it is possible that the expected reduced mitochondrial output under low-iron conditions may be yet another cause for the reduced Hst 5 susceptibility in deferasirox-treated fungal cells.

Various transition metals besides iron also play important roles in the pathobiology of OPC. However, our RNA-seq results did not show the differential expression of genes involved in response to other metals, such as zinc and copper (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). This is in line with the much greater affinity of deferasirox for iron than for Zn or Cu (35). This underscores the crucial role that iron plays in OPC, independent from other metals, and shows a promising role for deferasirox in treating OPC.

Furthermore, preventive treatment may be an option for individuals with a foreseeable risk of oral candidiasis or in individuals with high levels of oral C. albicans carriage that may make them vulnerable to systemic infections during hospitalizations for intensive care or while they are undergoing surgical procedures. Despite the known side effects of the drug, deferasirox treatment was well tolerated in a study involving healthy volunteers, with the levels of serum ferritin (a marker of an individual’s iron levels) remaining normal (36), thereby making preventive deferasirox treatment a practical approach in susceptible individuals with normal iron levels. Moreover, synergy between deferasirox and existing antifungal drugs may provide better candidacidal activity when both are administered together. We are currently investigating this potential possibility, using both in vitro and in vivo assays, with the understanding that the use of deferasirox for OPC by itself is unlikely. Nevertheless, this proof-of-concept study underscores the fact that iron chelation can potentially provide an alternative or, at the least, an adjunct antifungal therapy for OPC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Media and growth conditions.

Cells of the Candida albicans CAI4 URA strain (Δura3::imm434/Δura3::imm434RPS1/Δrps1::Clp10-URA3) were cultured for 12 h in yeast extract-peptone-dextrose (YPD) medium with 50 μg/ml of uridine and then used for murine infection as described below; YPD-uracil plates with antibiotics (streptomycin and penicillin diluted 0.5×; Sigma) were used for determination of the numbers of CFU. Overnight cultures of C. albicans in yeast nitrogen base (YNB) with 2% glucose were diluted to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.3 to 0.4 in fresh medium supplemented with deferasirox (0.07mg/ml) or not supplemented as a control and allowed to grow for 2 to 3 h to reach an OD600 of 0.6 to 0.7 for use in all in vitro experiments.

Murine model of OPC.

An immunosuppression model of murine OPC was used, as described previously (37), with the following modifications. Briefly, C57BL/6 mice (female, 4 to 6 weeks old) were immunosuppressed with 225 mg/kg of body weight of cortisone acetate (Sigma-Aldrich) on days −1, +1, and +3 before and after sublingual infection with C. albicans (1 × 107 cells/ml) for 1 h on day 0. Deferasirox (0.07 mg/ml) was provided in the drinking water with 2% dextrose for preventive or therapeutic treatment, as shown in Fig. 1. Carbachol (100 μl of 0.1 mg/ml) was administered intraperitoneally to stimulate saliva production, and saliva was collected by aspiration from the mouth. Animals were treated humanely, as per the protocols approved by the University at Buffalo (IACUC project no. ORB06042Y).

Salivary iron estimation.

Salivary iron levels were estimated using inductively coupled plasma resonance mass spectroscopy (ICP-MS), as described previously (16). Murine saliva was thawed, and 0.050 ml from each mouse was pipetted into an acid-cleaned polypropylene digestion tube. Control human saliva and samples of control human saliva spiked at 1 ng/ml were also digested and analyzed alongside study samples to demonstrate background concentrations and method accuracy. Nitric acid (Ultrex purity; Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) was added to each vial, and the samples were mixed and transferred to a temperature-controlled ultrasonic water bath. Next, the samples were heated to 60°C and allowed to digest for 30 min. The samples were allowed to cool, spiked with internal standard to a final concentration of 1 ng/ml of indium and scandium, and diluted to 5 ml with deionized water for trace metal analysis. Analysis was done using a Thermo Fisher Element 2 SF-ICP-MS system (Bremen, Germany) equipped with an ESI SC2-DX autosampler and a Peltier-cooled spray chamber, and all elements were monitored at medium resolution (m/Delta m = approximately 4,000, where the value m/Delta m [mass over difference in mass] represents the resolution power of the instrument during analysis, where m is the mass being measured and Delta m is the difference between two peaks being measured).

Tongue tissue collection and processing and CFU determination.

At day 5 after infection, mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation while they were under anesthesia, and their tongues were harvested and divided into two halves length-wise. One half was homogenized for determination of the number of CFU and myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity (described below), and the other half was fixed in formalin, paraffin embedded, and then sectioned and stained with PAS and H&E stain as previously described (38). For determination of the number of Candida CFU, one half of the tongue tissue was weighed, homogenized, and plated on yeast extract-peptone-dextrose (YPD) plates. CFU results were log transformed before statistical analysis by the Mann-Whitney U test. Results are presented as the mean number of log10 CFU ± standard deviation (SD).

MPO assay.

The activity of MPO, a surrogate marker of neutrophil infiltration, was measured as previously described (39). Briefly, previously weighed tongue tissue was incubated on ice in phosphate buffer containing hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide. Tissue samples were homogenized and then underwent three cycles of sonication and freeze-thawing. Cellular debris was removed by centrifugation. The MPO levels in the supernatants were then analyzed spectrophotometrically at 450 nm. Results were reported as the number of MPO units per gram of tongue tissue. The rate of H2O2 consumption was measured spectrophotometrically over a 5-min period.

RNA-seq.

Fungal plaques were harvested from infected murine tongues by gently lifting the fungal biomass from the underlying murine tissue with sterile forceps, followed by incubation with 1% Triton X-100 for 10 min at 23°C to lyse the murine cells. After incubation, the C. albicans cells were pelleted and resuspended in 1 ml of the TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies) for 5 min to further remove traces of murine cells and centrifuged again at 1,500 × g for 5 min. The cell pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of the TRIzol reagent and vortexed (4 cycles, 6 m/s) with 0.45-μm-diameter glass beads using a FastPrep-24 instrument (MP Biomedicals). Lysed cells (1 ml) were collected, chloroform (200 μl) was added, and the cells and chloroform were then mixed vigorously for 15 s and maintained for 2 to 3 min at room temperature. The cell lysate was centrifuged at 21,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C to separate the RNA-containing upper aqueous layer, which was collected and mixed with 0.5 volume of 100% ethanol to precipitate total RNA from the C. albicans cells. The total RNA was further purified using an RNeasy minikit from Qiagen according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The RNA samples were stored at −80°C for the next steps.

Total RNA was quantified using a RiboGreen assay (Invitrogen), and the quality of the RNA samples was checked using a Fragment Analyzer standard sensitivity assay (Advanced Analytical). An Illumina TruSeq RNA sample preparation kit (Illumina) was used to prepare cDNA libraries from RNA samples per the manufacturer’s instructions. The cDNA libraries were quantified using a PicoGreen assay (Invitrogen) and library quantification kit (Kappa Biosciences). A Fragment Analyzer high-sensitivity next-generation sequencing (NGS) kit (Advanced Analytical) was used to confirm the quality and the size of the cDNA libraries. The cDNA libraries were then normalized, multiplexed, and sequenced using an Illumina HiSeq2500 system following the manufacturer’s instructions at the UB Genomics and Bioinformatics Core Facility (Buffalo, NY). Raw RNA sequencing reads were generating using the Illumina HiSeq2500 system and a 50-cycle single-read flow cell.

The resulting sequencing reads were demultiplexed using Illumina’s bcl2fastq (v2.17.1.14) software. Reads for each sample were then reviewed for quality using FastQC (v0.11.5) software and mapped to the reference genome (C_albicans_SC5314_A22) using TopHat (v2.1.1) software. The resulting alignment files were then supplied to the Cuffdiff (v2.1.1) package, which calculates expression levels based on an input gene annotation file and tests the statistical significance of the observed changes. Annotations with a false discovery rate of <0.05 were considered significant.

Isolation of human neutrophils from peripheral blood.

Human peripheral blood was obtained from healthy volunteers (UB protocol IRB 626714) and collected in Vacuette EDTA tubes coated with K2EDTA (Greiner Bio-One). Next, blood was processed to obtain neutrophils using 1-step polymorphs (Accurate Chemical & Scientific Corporation) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The purity of the neutrophils was determined using Wright-Giemsa staining (Polysciences, Inc.). Neutrophils at a density of 1 × 106 cells/ml were suspendered in RPMI 1640 supplemented with l-glutamine (Corning Cellgro) and 10% fetal bovine serum (Seradigm) and seeded in a 24-well plate (Corning Inc.).

PI assay.

Phagocytic index (PI) assays were performed as previously described (40). C. albicans cells were then washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove any remaining medium, suspended in RPMI 1640, and counted in a hemocytometer. C. albicans cells were added to freshly isolated human neutrophils at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 3 for 30 min at 37°C in 5% CO2 to allow phagocytosis. After uptake, the neutrophil and C. albicans cell suspensions were collected and placed in positively charged slides (Globe Scientific Inc.) to allow attachment. Nonphagocytosed C. albicans cells were stained with calcofluor white (CW; Sigma-Aldrich) and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences) for 30 min. After fixation, the cells were permeabilized for 5 min with 0.1% Triton X-100 (Fisher Bioreagents) and stained with 4 mg/ml of Alexa Fluor 488-phalloidin (Invitrogen) to identify phagocytic cells. Finally, the cells were covered with a no. 1 cover glass (Knittel Glaeser) mounted with fluorescent mounting medium (Dako). On the next day, the PI was obtained by direct observation using a Zeiss Axio Observer Z1 inverted fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss, Germany). A minimum of 100 neutrophils was counted for each condition, and phagocytosed C. albicans cells (cells not stained with CW) were quantified. The PI was calculated as (total number of phagocytosed yeast cells/total number of neutrophils counted). Assays were performed in duplicate and in three independent experiments. Data were analyzed using Student's t test on GraphPad Prism (v7.0) software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

C. albicans survival within human neutrophils.

Overnight cultures of C. albicans in YNB medium were diluted and allowed to grow to exponential phase as described previously (40). C. albicans cells were then washed, suspended in RPMI 1640, and counted in a hemocytometer. Fungal cells were added to neutrophils at an MOI of 0.1 and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 3 h to allow killing. After 30 min of coincubation, cells were sampled to evaluate the PI as indicated above, and the total number of phagocytosed C. albicans was calculated as PI × total number of neutrophils added. After 3 h, sterile ice-cold water and 0.25% SDS were added to the cell suspensions in order to lyse the neutrophils and release phagocytosed C. albicans cells. The fungal cell suspension was collected and plated on YPD agar at 30°C for 24 h to obtain the number of viable CFU. Survival was obtained as (number of C. albicans CFU after 3 h/total number of phagocytosed C. albicans cells) × 100. Assays were performed in duplicate and in two independent experiments. Data were analyzed using Student's t test on GraphPad Prism (v7.0) software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

Epithelial cell adhesion and invasion.

The TR146 buccal epithelial squamous cell carcinoma line was obtained from the European Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures (ECACC). TR146 cells were routinely cultured in 1:1 Dulbecco modified Eagle medium–Ham’s F-12 medium (DMEM–F-12 medium) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator. For the experiments, TR146 epithelial cells were seeded at 1 × 105 cells/ml on sterile acid-washed 18-mm-diameter glass round coverslips (VistaVision; VWR) placed in a 12-well cell culture and cultured until the cells were confluent.

Adhesion assays were performed using a TR146 epithelial cell monolayer as described previously (41). Briefly, TR146 oral epithelial cells were grown to confluence on coverslips and were serum starved overnight prior to the experiment. Control and deferasirox-treated Candida cells (1 × 105 cells/ml) were added to confluent TR146 cells in 1 ml serum-free DMEM–F-12 medium. C. albicans cells were allowed to infect TR146 cells for 90 min and 4.5 h for adhesion and invasion, respectively. After incubation, nonadherent C. albicans cells were removed and washed three times with 1× PBS and fixed with 4% formaldehyde. For staining, Candida cells were incubated with rabbit anti-Candida antibody (1:1,000) for 2 h and subsequently with a goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin–Alexa Fluor 488 antibody (1:2,000) for 1 h at room temperature. After staining, the cells in the TR146 cell monolayer were permeabilized using 0.1% Triton X-100 for 20 min at 37°C in the dark. The coverslips were rinsed in water, mounted on slides using 1 to 2 drops of fluorescent mounting medium (Dako), and allowed to air dry for 1 to 2 h. The slides were documented using a Zeiss Axio Observer Z1 microscope. Adhesion was calculated as the percentage of cells that adhered in relation to the total number of cells. The percentage of invading Candida cells was determined by dividing the number of invading cells by the total number of adherent cells. A minimum of 500 Candida cells was counted to calculate percent invasion.

Hydrogen peroxide assay.

C. albicans susceptibility to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was evaluated as previously described (42) with modifications. Briefly, mid-log-phase C. albicans (control and deferasirox-treated) cells were washed three times with 1× PBS and counted in a hemocytometer. Cells were suspended at 1 × 107 cells/ml in YPD medium supplemented with 1, 2.5, 5, or 10 mM H2O2 (Sigma-Aldrich) and incubated for 2 h at 30°C with shaking. Control samples were treated similarly but incubated without H2O2. The cells were then serially diluted in PBS, and 100 μl of the suspension was plated on YPD agar. The plates were incubated at 30°C for 24 h to obtain the number of viable CFU.

HNP-1 killing assay.

Human neutrophil peptide 1 (HNP-1) candidacidal activity was evaluated as described previously (43) with minor modifications. Overnight cultures were diluted to an OD600 of 0.3 to 0.4 in fresh YPD medium and then regrown to reach an OD600 of 0.8 to 1.0. The cells were washed three times with 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (NaPB), pH 7.4. A total of 1.5 × 106 cells/ml were suspended in NaPB with 0.5, 1, or 2.5 μM HNP-1 (Anaspec, Inc.), and control samples were left without HNP-1. Cells were incubated at 37°C with shaking at 220 rpm for 1 h. The cells were then diluted in 10 mM NaPB, and the cells were plated onto YPD agar. The plates were incubated for 24 h at 30°C, and the numbers of CFU were obtained.

Histatin 5 (Hst 5) killing assay.

Hst 5 killing assays were performed as described previously (13).

Accession number(s).

The data described here have been deposited in NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database and are accessible through GEO series accession number GSE123277 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc= GSE123277).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants R01DE010641 and R01DE022720 to M.E. and R03DE026451 to S.P. from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health.

We thank Jason Kay for his guidance in the neutrophil assays and Novartis, Basel, Switzerland, for generously providing deferasirox.

We declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

S. Puri contributed to study design, data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation and drafted and critically revised the manuscript; R. Kumar, I. G. Rojas, and O. Salvatori contributed to data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation and drafted the manuscript; M. Edgerton contributed to study design, data analysis, and interpretation and critically revised the manuscript. All authors gave final approval and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.02152-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ghannoum MA, Jurevic RJ, Mukherjee PK, Cui F, Sikaroodi M, Naqvi A, Gillevet PM. 2010. Characterization of the oral fungal microbiome (mycobiome) in healthy individuals. PLoS Pathog 6:e1000713. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ben-Ami R. 2018. Treatment of invasive candidiasis: a narrative review. J Fungi (Basel) 4:E97. doi: 10.3390/jof4030097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miranda LN, van der Heijden IM, Costa SF, Sousa AP, Sienra RA, Gobara S, Santos CR, Lobo RD, Pessoa VP Jr, Levin AS. 2009. Candida colonisation as a source for candidaemia. J Hosp Infect 72:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nucci M, Anaissie E. 2001. Revisiting the source of candidemia: skin or gut? Clin Infect Dis 33:1959–1967. doi: 10.1086/323759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roemer T, Krysan DJ. 2014. Antifungal drug development: challenges, unmet clinical needs, and new approaches. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 4:a019703. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a019703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Oliveira Santos GC, Vasconcelos CC, Lopes AJO, de Sousa Cartagenes MDS, Filho A, do Nascimento FRF, Ramos RM, Pires E, de Andrade MS, Rocha FMG, de Andrade Monteiro C. 2018. Candida infections and therapeutic strategies: mechanisms of action for traditional and alternative agents. Front Microbiol 9:1351. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen C, Pande K, French SD, Tuch BB, Noble SM. 2011. An iron homeostasis regulatory circuit with reciprocal roles in Candida albicans commensalism and pathogenesis. Cell Host Microbe 10:118–135. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lan CY, Rodarte G, Murillo LA, Jones T, Davis RW, Dungan J, Newport G, Agabian N. 2004. Regulatory networks affected by iron availability in Candida albicans. Mol Microbiol 53:1451–1469. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Puri S, Lai WK, Rizzo JM, Buck MJ, Edgerton M. 2014. Iron-responsive chromatin remodelling and MAPK signalling enhance adhesion in Candida albicans. Mol Microbiol 93:291–305. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaba HE, Nimtz M, Muller PP, Bilitewski U. 2013. Involvement of the mitogen activated protein kinase Hog1p in the response of Candida albicans to iron availability. BMC Microbiol 13:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-13-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramanan N, Wang Y. 2000. A high-affinity iron permease essential for Candida albicans virulence. Science 288:1062–1064. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5468.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Velliyagounder K, Alsaedi W, Alabdulmohsen W, Markowitz K, Fine DH. 2015. Oral lactoferrin protects against experimental candidiasis in mice. J Appl Microbiol 118:212–221. doi: 10.1111/jam.12666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Puri S, Li R, Ruszaj D, Tati S, Edgerton M. 2015. Iron binding modulates candidacidal properties of salivary histatin 5. J Dent Res 94:201–208. doi: 10.1177/0022034514556709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bairwa G, Hee Jung W, Kronstad JW. 2017. Iron acquisition in fungal pathogens of humans. Metallomics 9:215–227. doi: 10.1039/c6mt00301j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Norimatsu Y, Kawashima J, Takano-Yamamoto T, Takahashi N. 2015. Nitrogenous compounds stimulate glucose-derived acid production by oral Streptococcus and Actinomyces. Microbiol Immunol 59:501–506. doi: 10.1111/1348-0421.12283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Norris HL, Friedman J, Chen Z, Puri S, Wilding G, Edgerton M. 2018. Salivary metals, age, and gender correlate with cultivable oral Candida carriage levels. J Oral Microbiol 10:1447216. doi: 10.1080/20002297.2018.1447216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hong JH, Kim KO. 2011. Operationally defined solubilization of copper and iron in human saliva and implications for metallic flavor perception. Eur Food Res Technol 233:973–983. doi: 10.1007/s00217-011-1590-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharp P, Tandy S, Yamaji S, Tennant J, Williams M, Singh Srai SK. 2002. Rapid regulation of divalent metal transporter (DMT1) protein but not mRNA expression by non-haem iron in human intestinal Caco-2 cells. FEBS Lett 510:71–76. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(01)03225-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alexander J, Limaye AP, Ko CW, Bronner MP, Kowdley KV. 2006. Association of hepatic iron overload with invasive fungal infection in liver transplant recipients. Liver Transpl 12:1799–1804. doi: 10.1002/lt.20827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kontoghiorghes GJ, Kolnagou A, Skiada A, Petrikkos G. 2010. The role of iron and chelators on infections in iron overload and non iron loaded conditions: prospects for the design of new antimicrobial therapies. Hemoglobin 34:227–239. doi: 10.3109/03630269.2010.483662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ibrahim AS, Gebermariam T, Fu Y, Lin L, Husseiny MI, French SW, Schwartz J, Skory CD, Edwards JE Jr, Spellberg BJ. 2007. The iron chelator deferasirox protects mice from mucormycosis through iron starvation. J Clin Invest 117:2649–2657. doi: 10.1172/JCI32338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lai YW, Campbell LT, Wilkins MR, Pang CN, Chen S, Carter DA. 2016. Synergy and antagonism between iron chelators and antifungal drugs in Cryptococcus. Int J Antimicrob Agents 48:388–394. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2016.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Savage KA, Del Carmen Parquet M, Allan DS, Davidson RJ, Holbein BE, Lilly EA, Fidel PL Jr. 2018. Iron restriction to clinical isolates of Candida albicans by the novel chelator DIBI inhibits growth and increases sensitivity to azoles in vitro and in vivo in a murine model of experimental vaginitis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 62:e02576-17. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02576-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Skrzypek MS, Binkley J, Binkley G, Miyasato SR, Simison M, Sherlock G. 2017. The Candida Genome Database (CGD): incorporation of Assembly 22, systematic identifiers and visualization of high throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res 45:D592–D596. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knight SA, Lesuisse E, Stearman R, Klausner RD, Dancis A. 2002. Reductive iron uptake by Candida albicans: role of copper, iron and the TUP1 regulator. Microbiology 148:29–40. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-1-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weissman Z, Kornitzer D. 2004. A family of Candida cell surface haem-binding proteins involved in haemin and haemoglobin-iron utilization. Mol Microbiol 53:1209–1220. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Srikantha T, Borneman AR, Daniels KJ, Pujol C, Wu W, Seringhaus MR, Gerstein M, Yi S, Snyder M, Soll DR. 2006. TOS9 regulates white-opaque switching in Candida albicans. Eukaryot Cell 5:1674–1687. doi: 10.1128/EC.00252-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoyer LL, Cota E. 2016. Candida albicans agglutinin-like sequence (Als) family vignettes: a review of Als protein structure and function. Front Microbiol 7:280. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Almeida RS, Brunke S, Albrecht A, Thewes S, Laue M, Edwards JE, Filler SG, Hube B. 2008. The hyphal-associated adhesin and invasin Als3 of Candida albicans mediates iron acquisition from host ferritin. PLoS Pathog 4:e1000217. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fanning S, Xu W, Solis N, Woolford CA, Filler SG, Mitchell AP. 2012. Divergent targets of Candida albicans biofilm regulator Bcr1 in vitro and in vivo. Eukaryot Cell 11:896–904. doi: 10.1128/EC.00103-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao X, Oh SH, Yeater KM, Hoyer LL. 2005. Analysis of the Candida albicans Als2p and Als4p adhesins suggests the potential for compensatory function within the Als family. Microbiology 151:1619–1630. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27763-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Granger BL. 2012. Insight into the antiadhesive effect of yeast wall protein 1 of Candida albicans. Eukaryot Cell 11:795–805. doi: 10.1128/EC.00026-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gleason JE, Galaleldeen A, Peterson RL, Taylor AB, Holloway SP, Waninger-Saroni J, Cormack BP, Cabelli DE, Hart PJ, Culotta VC. 2014. Candida albicans SOD5 represents the prototype of an unprecedented class of Cu-only superoxide dismutases required for pathogen defense. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:5866–5871. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400137111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Puri S, Edgerton M. 2014. How does it kill?: understanding the candidacidal mechanism of salivary histatin 5. Eukaryot Cell 13:958–964. doi: 10.1128/EC.00095-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taher A, Cappellini MD. 2009. Update on the use of deferasirox in the management of iron overload. Ther Clin Risk Manag 5:857–868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sechaud R, Robeva A, Belleli R, Balez S. 2008. Absolute oral bioavailability and disposition of deferasirox in healthy human subjects. J Clin Pharmacol 48:919–925. doi: 10.1177/0091270008320316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tati S, Li R, Puri S, Kumar R, Davidow P, Edgerton M. 2014. Histatin 5-spermidine conjugates have enhanced fungicidal activity and efficacy as a topical therapeutic for oral candidiasis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:756–766. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01851-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dwivedi PP, Mallya S, Dongari-Bagtzoglou A. 2009. A novel immunocompetent murine model for Candida albicans-promoted oral epithelial dysplasia. Med Mycol 47:157–167. doi: 10.1080/13693780802165797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilgus TA, Parrett ML, Ross MS, Tober KL, Robertson FM, Oberyszyn TM. 2002. Inhibition of ultraviolet light B-induced cutaneous inflammation by a specific cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor. Adv Exp Med Biol 507:85–92. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0193-0_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pathirana RU, Friedman J, Norris HL, Salvatori O, McCall AD, Kay J, Edgerton M. 2018. Fluconazole-resistant Candida auris is susceptible to salivary histatin 5 killing and to intrinsic host defenses. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 62:e01872-17. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01872-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moyes DL, Wilson D, Richardson JP, Mogavero S, Tang SX, Wernecke J, Hofs S, Gratacap RL, Robbins J, Runglall M, Murciano C, Blagojevic M, Thavaraj S, Forster TM, Hebecker B, Kasper L, Vizcay G, Iancu SI, Kichik N, Hader A, Kurzai O, Luo T, Kruger T, Kniemeyer O, Cota E, Bader O, Wheeler RT, Gutsmann T, Hube B, Naglik JR. 2016. Candidalysin is a fungal peptide toxin critical for mucosal infection. Nature 532:64–68. doi: 10.1038/nature17625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Phillips AJ, Crowe JD, Ramsdale M. 2006. Ras pathway signaling accelerates programmed cell death in the pathogenic fungus Candida albicans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:726–731. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506405103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Edgerton M, Koshlukova SE, Araujo MW, Patel RC, Dong J, Bruenn JA. 2000. Salivary histatin 5 and human neutrophil defensin 1 kill Candida albicans via shared pathways. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 44:3310–3316. doi: 10.1128/AAC.44.12.3310-3316.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.