Hypermutable Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates (hypermutators) have been identified in patients with cystic fibrosis (CF) and are associated with reduced lung function. Hypermutators display a greatly increased mutation rate and an enhanced ability to become resistant to antibiotics during treatment.

KEYWORDS: Pseudomonas aeruginosa, antibiotic resistance, cystic fibrosis, hypermutation, multidrug resistance, whole-genome sequencing

ABSTRACT

Hypermutable Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates (hypermutators) have been identified in patients with cystic fibrosis (CF) and are associated with reduced lung function. Hypermutators display a greatly increased mutation rate and an enhanced ability to become resistant to antibiotics during treatment. Their prevalence has been established among patients with CF, but it has not been determined for patients with CF in Australia. This study aimed to determine the prevalence of hypermutable P. aeruginosa isolates from adult patients with CF from a health care institution in Australia and to characterize the genetic diversity and antibiotic susceptibility of these isolates. A total of 59 P. aeruginosa clinical isolates from patients with CF were characterized. For all isolates, rifampin (RIF) mutation frequencies and susceptibility to a range of antibiotics were determined. Of the 59 isolates, 13 (22%) were hypermutable. Whole-genome sequences were determined for all hypermutable isolates. Core genome polymorphisms were used to assess genetic relatedness of the isolates, both to each other and to a sample of previously characterized P. aeruginosa strains. Phylogenetic analyses showed that the hypermutators were from divergent lineages and that hypermutator phenotype was mostly the result of mutations in mutL or, less commonly, in mutS. Hypermutable isolates also contained a range of mutations that are likely associated with adaptation of P. aeruginosa to the CF lung environment. Multidrug resistance was more prevalent in hypermutable than nonhypermutable isolates (38% versus 22%). This study revealed that hypermutable P. aeruginosa strains are common among isolates from patients with CF in Australia and are implicated in the emergence of antibiotic resistance.

INTRODUCTION

Pseudomonas aeruginosa frequently causes chronic pulmonary infections that are associated with increased morbidity and mortality among patients with suppurative lung diseases, especially those with cystic fibrosis (CF) (1, 2). Patients with CF have frequently been found to harbor hypermutable P. aeruginosa strains (3–6), a finding generally associated with poorer patient outcomes (7, 8). These hypermutators show an increased mutation rate of up to 1,000-fold compared to that of wild-type strains (6) and this, together with the short bacterial generation time, allows them to rapidly adapt to a variety of stressful environments (9). Hence, hypermutable P. aeruginosa strains can quickly adapt to antibiotic exposure (4), and these strains have been strongly linked with antibiotic resistance within patients with CF (3, 4, 6, 7).

The hypermutator phenotype results from the mutation of genes involved in DNA repair, especially genes involved in the mismatch repair (MMR) system (mutS, mutL, and uvrD) (10, 11). Mutations in the 7,8-dihydro-8-oxo-deoxyguanosine (8-oxodG or GO) system genes, mutM, mutY, and mutT, have also been found to produce the hypermutator phenotype in P. aeruginosa (12). P. aeruginosa cells show a variety of diverse phenotypic changes associated with adaptation to the CF lung, including conversion to a mucoid phenotype (13, 14), inactivation of quorum-sensing functions (15–17), motility loss (18, 19), and various auxotrophies (20). Common mutation-mediated antibiotic resistance mechanisms include the increased expression of Mex-efflux pumps following mutations in regulator genes (21–23), antibiotic-binding-site modifications (24), increased production of antibiotic inactivating β-lactamase enzymes (25), and inactivation of outer membrane porins that lead to cell membrane permeability changes and reduced intracellular drug accumulation (23). These phenotypic changes may occur more readily in hypermutator strains due to the increased mutation rates.

The prevalence of P. aeruginosa hypermutators in isolates from patients with CF has been examined across several clinics in Europe (15% to 54%; average, 27%) (4, 7, 8, 10, 26–29) and the Americas (17% to 42%; average, 29%) (9, 30, 31). However, the prevalence and genetic diversity of hypermutator isolates obtained from patients with CF in Australia have received much less attention. Previously, four Australian isolates were included in a European multicenter study; however, only mutation frequencies (MF) were determined for these isolates, and there was no description of the individual results (32). Another multinational study, which assessed eight P. aeruginosa isolates belonging to a single widespread clone (clonal complex 274 [CC274]), including three hypermutators obtained in 2007 to 2008 from different geographical locations in Australia, determined the phylogeny, interpatient dissemination, and hypermutator and resistance genotypes (33).

Antibiotic resistance in P. aeruginosa is a major problem in Australian CF centers (34). Given the importance of hypermutator P. aeruginosa strains for antibiotic resistance and poorer patient outcomes, we aimed to determine the prevalence of hypermutators among isolates obtained in 2013 from chronically infected adult patients with CF at a major health care center in Australia and to characterize and evaluate the cause of hypermutation. Each of the isolates was tested for susceptibility to a panel of antibiotics, and whole-genome sequencing (WGS) with comparative genomic and phylogenetic analyses was used to further characterize the hypermutators. This report describes for the first time the prevalence of hypermutable P. aeruginosa isolates from patients with CF in an Australian health care center and the comprehensive genotypic and phenotypic characterization of these isolates.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Prevalence and resistance profiles of P. aeruginosa hypermutators in patients with CF from Australia.

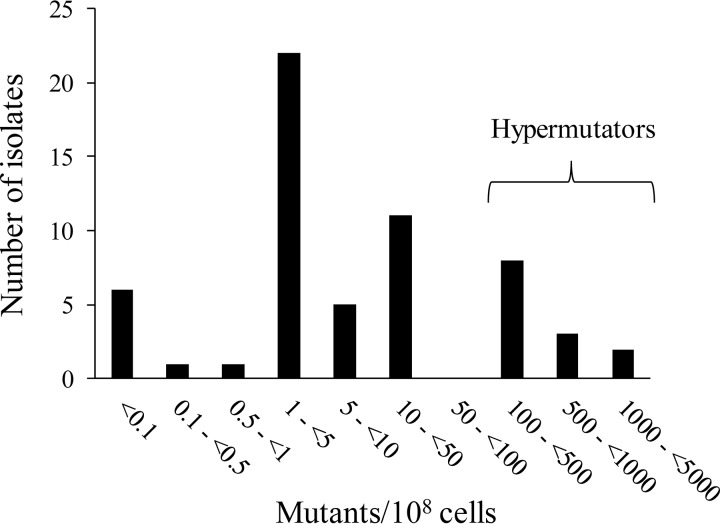

Of a total of 59 consecutive P. aeruginosa isolates (designated CW1 to CW59) from 37 patients with CF (22 patients had both a mucoid and nonmucoid colony variant included from their sputum culture) who attended the Alfred Hospital in 2013, 13 isolates (22%) from 10 patients (27%) were found to be hypermutable (Table 1). Of the mucoid and nonmucoid colony variant pairs from 22 patients, in three patients both were hypermutators, in six patients only one of them was a hypermutator, and in 13 of the patients both were nonhypermutators. All of the isolates defined as hypermutable showed at least a 48-fold increase in MF compared to that of PAO1, while the highest MF in the nonhypermutator isolates was 8-fold that of PAO1. Furthermore, analysis of the total number of rifampin (RIF)-resistant mutants per 108 bacterial cells (Fig. 1) showed that the definition of hypermutation (rifampin MF ≥ 20-fold higher than that for PAO1 [4]) allows a very clear distinction between hypermutable and nonhypermutable isolates. Of the 13 hypermutable isolates, 9 showed more than a 100-fold MF increase, with CW35 showing the highest MF of 470-fold that of PAO1. Our results agreed very well with those for patients with CF in Spain, where on average 21% (range 15% to 29%) of isolates were hypermutable and 30% (24% to 37%) of patients harbored hypermutable strains (4, 26, 27).

TABLE 1.

The bacterial characteristics of 59 clinical P. aeruginosa isolates from patients with cystic fibrosis

| Isolatea | Patient no. | Mucoid phenotypeb | RIF MF (fold change)c | MIC for: |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATMd,e | CAZd,f | CIPd,e | MEMd,e | TOBd,e | ||||

| CW1 | 1 | N | 0.8 | 4 | >256 | 0.75 | 8 | 12 |

| CW2 | 2 | Mi | 0.4 | 0.016 | 0.032 | 0.047 | 0.016 | 2 |

| CW3 | 3 | M | 6.2 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.75 |

| CW4 | 4 | N | 1.5 | 8 | 2 | 1.5 | 0.25 | 6 |

| CW5 | 5 | N | 285.2 | 6 | >256 | 1.5 | >32 | 3 |

| CW6 | 5 | M | 0.5 | 24 | >256 | 4 | 12 | 3 |

| CW7 | 6 | Mi | 1.2 | 1.5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.032 |

| CW8 | 6 | N | 141.0 | 1.5 | 0.75 | 4 | 1.5 | 0.75 |

| CW9 | 7 | N | 1.0 | 16 | 4 | 0.25 | 0.19 | 0.75 |

| CW10 | 7 | Mi | 1.0 | 6 | >256 | 4 | 0.125 | 0.75 |

| CW11 | 8 | M | 2.3 | 8 | 12 | 0.094 | 0.75 | 3 |

| CW12 | 9 | M | 2.2 | 0.19 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 0.125 | 1 |

| CW13 | 10 | N | 180.5 | 0.5 | 24 | 4 | 8 | 1.5 |

| CW14 | 10 | M | 0.6 | 0.047 | 0.25 | 1.5 | 0.125 | 1 |

| CW15 | 11 | M | 4.4 | 4 | 1.5 | 2 | 0.094 | 1.5 |

| CW16 | 12 | M | 4.8 | 0.125 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.125 | 3 |

| CW17 | 13 | N | 7.5 | 0.5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| CW18 | 13 | M | 3.2 | 0.19 | 1 | 1.5 | 0.064 | 1 |

| CW19 | 14 | M | 76.9 | 1 | 16 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 1 |

| CW20 | 14 | N | 0.7 | 8 | >256 | 0.25 | 16 | 8 |

| CW21 | 15 | M | 2.7 | 0.125 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.5 | 1.5 |

| CW22 | 15 | N | 0.5 | 12 | 16 | 1 | >32 | 32 |

| CW23 | 16 | M | 2.6 | 0.064 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.032 | 0.38 |

| CW24 | 16 | N | 1.0 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.047 | 2 |

| CW25 | 17 | M | 1.9 | 0.032 | 0.125 | 0.75 | 1.5 | 1 |

| CW26 | 18 | N | 1.4 | 0.75 | 2 | 1.5 | >32 | 24 |

| CW27 | 18 | M | 1.9 | 0.19 | 0.38 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| CW28 | 19 | N | 125.9 | 12 | >256 | 3 | >32 | 3 |

| CW29 | 19 | M | 1.0 | 0.75 | 2 | 0.19 | 4 | 2 |

| CW30 | 20 | N | 84.9 | 0.032 | 0.064 | 1 | 0.016 | 0.75 |

| CW31 | 20 | Mi | 143.9 | 0.064 | 0.094 | 0.094 | 0.004 | 1 |

| CW32 | 21 | N | 2.8 | 16 | 12 | 1.5 | >32 | 2 |

| CW33 | 21 | M | 6.2 | 0.19 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.125 | 3 |

| CW34 | 22 | N | 240.0 | 0.38 | 1 | 4 | 0.5 | 8 |

| CW35 | 22 | Mi | 472.5 | 0.19 | 1.5 | 3 | 0.5 | 8 |

| CW36 | 23 | N | 6.5 | 0.75 | 4 | 1.5 | 0.75 | >256 |

| CW37 | 23 | M | 2.3 | 0.5 | 0.38 | 0.5 | 0.125 | >256 |

| CW38 | 24 | M | 1.7 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 3 |

| CW39 | 24 | N | 1.1 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 0.5 | 16 |

| CW40 | 25 | N | 2.1 | 1 | 0.75 | >32 | 0.64 | 24 |

| CW41 | 26 | Mi | 48.4 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 4 | 0.75 | 16 |

| CW42 | 26 | N | 54.5 | 2 | >256 | 6 | >32 | 48 |

| CW43 | 27 | M | 0.9 | 0.19 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 1 | 3 |

| CW44 | 28 | Mi | 122.6 | 1.5 | 2 | 0.19 | 0.5 | 1 |

| CW45 | 29 | N | 232.5 | 16 | >256 | 1.5 | >32 | 8 |

| CW46 | 29 | M | 0.8 | 3 | 8 | 1.5 | 2 | 2.5 |

| CW47 | 30 | Mi | 5.4 | 0.094 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.023 | 4 |

| CW48 | 30 | M | 4.4 | 0.023 | 0.125 | 0.5 | 0.23 | >256 |

| CW49 | 31 | N | 3.1 | 0.19 | 0.75 | 0.094 | 0.32 | 4 |

| CW50 | 31 | M | 3.0 | 0.19 | 0.75 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 3 |

| CW51 | 32 | Mi | 4.2 | 0.19 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.032 | 2 |

| CW52 | 33 | Mi | 2.7 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 0.032 | 1.5 |

| CW53 | 34 | M | 7.8 | 0.38 | 2 | 4 | 0.19 | 1.5 |

| CW54 | 34 | N | 0.4 | 0.5 | 2 | 8 | 3 | 1.5 |

| CW55 | 35 | N | 0.7 | 32 | >256 | 6 | 0.125 | 1.5 |

| CW56 | 36 | M | 5.1 | 0.38 | 0.5 | 4 | 0.125 | 3 |

| CW57 | 36 | N | 1.7 | 12 | 0.75 | 4 | 0.38 | 1 |

| CW58 | 37 | Mi | 2.0 | 0.125 | 0.75 | 1 | 1.5 | 2 |

| CW59 | 37 | N | 1.8 | 0.125 | 0.75 | 1 | 1.5 | 2 |

Hypermutator strains are indicated in bold.

Mucoid phenotype; M, mucoid; N, nonmucoid; Mi, nonmucoid revertants, i.e., mucoid isolates that reverted to nonmucoid. There were significantly more nonmucoid revertants from mucoid phenotype for hypermutators than for nonhypermutators (one-tailed Mann-Whitney U test, P = 0.004).

Mutation frequencies (MF) were determined as the fraction of the resistant population quantified on rifampin (300 mg/liter)-containing CAMHA plates compared to the total population quantified on drug-free CAMHA plates. Hypermutation was defined by the rifampin MF being ≥20-fold higher than that of PAO1.

MICs were interpreted based on EUCAST susceptibility breakpoints (56). MICs indicative of resistance are underlined and MICs indicative of intermediate resistance are shown in italics. Antibiotics tested: ATM, aztreonam; CAZ, ceftazidime; CIP, ciprofloxacin; MEM, meropenem; TOB, tobramycin.

Hypermutators were not significantly more resistant (Mann-Whitney U test, P > 0.05).

Hypermutators were significantly more ceftazidime resistant (one-tailed Mann-Whitney U test, P = 0.021).

FIG 1.

The number of isolates for each range of rifampin-resistant mutants per 108 bacterial cells, determined for each of the 59 clinical isolates. PAO1 showed 2.5 mutants/108 cells and PAOΔmutS showed 2,631.2 mutants/108 cells.

The Etest MIC values (Table 1) were used to determine multidrug resistance (MDR; nonsusceptibility to ≥1 agent from ≥3 different antimicrobial categories [35]). The percentages of nonsusceptible isolates in hypermutable compared to nonhypermutable strains, respectively, were 77% versus 65% for ciprofloxacin (CIP), 46% versus 17% for ceftazidime (CAZ), 46% versus 33% for aztreonam (ATM), 38% versus 20% for meropenem (MEM), and 38% versus 22% for tobramycin (TOB). These results are in agreement with previous studies that found greater resistance to antimicrobial agents for hypermutators compared to nonhypermutators (4, 31). However, in the present study, only reduced susceptibility to ceftazidime was found to be significantly greater for hypermutators compared to nonhypermutators (one-tailed Mann-Whitney U test, P = 0.021). Multidrug-resistant strains were more abundant among hypermutators (38%) than nonhypermutators (22%), in agreement with a previous study (7), although this difference did not reach statistical significance (one-tailed Mann-Whitney U test, P = 0.096).

Phylogenomic analysis.

The evolutionary relatedness of the 13 hypermutable clinical isolates, as determined using draft WGS, compared with 63 publicly available P. aeruginosa genomes (including those of PAO1 and ATCC 27853 wild-type strains) is displayed in Fig. S1. A maximum likelihood phylogeny was determined by comparison of all core genome single-nucleotide polymorphisms (cgSNPs), with PAO1 used as the reference genome. The 13 hypermutable isolates were spread widely across the phylogenetic tree, indicating that they arose from diverse P. aeruginosa strain backgrounds. Of the three paired hypermutator isolates (CW30 and CW31, CW34 and CW35, and CW41 and CW42), each of the individual isolates of a pair clustered closely together, indicating that they are likely to be true isogenic derivatives. Indeed, the average number of cgSNPs between all of the nonpaired hypermutator isolates was 24,641, while the average number of cgSNPs between the paired isolates was more than 30-fold less (774). However, the three hypermutator pairs were not closely related, indicating that they each arose from different backgrounds. CW8 and CW13 were found to be clustered closely with an Australian epidemic strain, AES-1R_NZ (36). CW41 and CW42 clustered closely with the Denmark epidemic strain DK2 (37, 38). Similarities with P. aeruginosa genomes from different environments around the world demonstrated diversity between these isolates (Fig. S1).

Mutations responsible for the hypermutator phenotype.

Genes likely to be involved in the hypermutator phenotypes are presented in Table S1. Complementation assays confirmed that for 9 of the 13 hypermutable isolates, the cause of hypermutation was linked to defects in either mutL (6 isolates) or mutS (3 isolates) (Table 2). Six of the isolates had inactivating mutations within mutL (CW8, CW19, and CW45 had frameshift mutations, CW30 and CW31 had an identical nonsense mutation, and CW44 had a large deletion), one isolate (CW5) had a frameshift mutation within mutS, and isolates CW34 and CW35 harbored two previously observed mutations that lead to missense substitutions in MutS (C224R and T287P) (33). Conversely, mutations within mutL in isolates CW41 and CW42 were confirmed to not be involved in the hypermutator phenotype, although the mutation at nucleotide (nt) 247 results in a K83E substitution in the ATPase domain (ATPlid) of MutL (39). Finally, several attempts to electroporate the plasmids for the complementation assays into isolate CW13 failed, and thus the effect of the A470V substitution within MutL could not be assessed.

TABLE 2.

Genetic analysis of mutS (PA3620) and mutL (PA4946) in the 13 hypermutator isolates

| Isolate | DNA sequence changea or predicted amino acid changes resulting from mutations inc: |

Complementation withb: |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mutS | mutL | mutS | mutL | |

| CW5 | nt1312Δ13 | A213V | + | − |

| CW8 | nt700Δ4 | − | + | |

| CW13 | A470V | ND | ND | |

| CW19 | nt1444ins1 | − | + | |

| CW28 | − | − | ||

| CW30 | Q341X | − | + | |

| CW31 | Q341X | − | + | |

| CW34 | C224R, T287P | + | − | |

| CW35 | C224R, T287P | + | − | |

| CW41 | P249L | K83E | − | − |

| CW42 | K83E | − | − | |

| CW44 | nt691Δ378 | − | + | |

| CW45 | nt565Δ1 | − | + | |

Sequence variations from the reference strain PAO1.

ND, not determined.

Inactivating mutations are shown in bold. nt, nucleotide; X, early STOP codon; Δ, nucleotide deletion; ins, nucleotide insertion.

The observation that mutations in mutL were the most common cause of hypermutability is in agreement with another study, where 60% of hypermutable isolates were attributed to mutations in mutL and the remaining 40% to mutS (31). However, other studies have found that hypermutation was more commonly due to a defective mutS gene (6, 11). Interestingly, our mutS-associated hypermutator isolates (CW5, CW34, and CW35) had the highest rifampin MF.

Apart from mutations within the mutS and mutL genes, several unique mutations leading to missense amino acid changes were documented in other mutator-associated genes (shown in Table S1, online supplement) that may also contribute to the hypermutator phenotype. The mechanism of hypermutation in paired weak hypermutators CW41 and CW42 may be linked to mutations within these other mutator genes, while in CW28 it may be due to mutations in unknown genes that are related to a strong hypermutator phenotype. Further studies are required to determine the definite cause for hypermutation in these strains.

Mutations in genes associated with the mucoid phenotype and quorum sensing.

The overview of mutations in genes involved in the mucoid phenotype and quorum sensing is shown in Table S1. Mucoidy is a common trait of P. aeruginosa isolates obtained from respiratory infections in patients with CF and occurs when there is increased alginate biosynthesis (28, 31, 40). This can result from inactivating mutations in the mucA gene, encoding the anti-sigma factor (anti-σ22), increased expression of the sigma factor (σ22) algU (or algT), or various mutations within the multicomponent signal transduction genes (algR or algP), which give rise to increased alginate production through the activation of the algD promoter (14).

Within the whole CF collection, 34 isolates (58%) exhibited a mucoid phenotype, and 10 of these displayed nonmucoid reversion (Table 1). Nonmucoid revertants are mucoid isolates that revert to the nonmucoid phenotype after acquiring additional mutations, likely in genes associated with alginate regulation and synthesis, along with the selective pressure for nonmucoid cells in aerobic, stationary cultures, like those experienced after isolation (41). Five of the hypermutators (38%) were found to show a mucoid phenotype, with four of these being nonmucoid revertants. In contrast, 29 nonhypermutable isolates (63%) exhibited a mucoid phenotype, with only six reverting to the nonmucoid phenotype (Table 1). The nonmucoid revertants were significantly more common for hypermutators than for nonhypermutators (one-tailed Mann-Whitney U test, P = 0.004). This relationship between hypermutation and nonmucoid reversion has been observed previously, where only hypermutators exhibited this reversion (42). It is likely that this reversion occurs more easily in hypermutators due to the increased chance of a spontaneous mutation arising in the mucoid-associated genes. The mucoid, hypermutable CW19 strain had a nonsense mutation in mucA (encoding the anti-sigma factor) and a large deletion in algP, which encodes the alginate transcriptional regulator (Table S1). Nonmucoid and nonmucoid revertant hypermutator isolates also contained inactivating mutations in a range of mucoid phenotype-related genes. Indeed, over half (54%) of the hypermutable isolates had frameshift or nonsense mutations in mucA. Of note, the nonmucoid revertant CW35 strain had no mutation in mucA, suggesting that mutations in other alginate biosynthesis or regulatory genes may have resulted in the original mucoid conversion and subsequent reversion. CW5, CW30, and CW45 showed a defective mucA gene with no observable mucoid conversion displayed, suggesting that these isolates underwent further adaptive mutations in the lungs of patients, making them nonmucoid revertants prior to their collection.

Four hypermutable isolates (CW30, CW31, CW41, and CW42) had no identifiable lasR gene (Table S1), which encodes the major quorum-sensing regulator (16). Three hypermutable isolates had inactivating mutations in lasR; CW28 had a frameshift mutation, while CW5 and CW45 had an identical nonsense mutation. CW19, CW34, CW35, and CW44 all had missense mutations in the section of lasR that encodes the DNA-binding domain, with the paired isolates CW34 and CW35 displaying an identical missense mutation. All of these mutations likely resulted in nonfunctional or highly reduced quorum-sensing activity (43). There has been discordance in the literature over whether the mucoid phenotype and quorum sensing are associated with a hypermutator phenotype (8, 28, 31). One of these studies found that mutations in mucA and lasR occurred prior to the acquisition of the hypermutator phenotype of P. aeruginosa isolates from patients with CF (28). A limitation of the present study is that we cannot determine the order of appearance of the mutations in our isolates to comment on whether the acquisition of the hypermutator phenotype or the mutations came first.

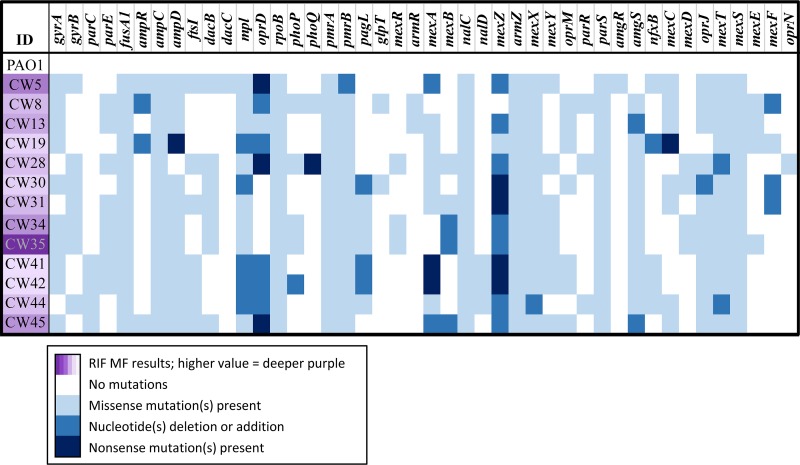

Mutations involved in antibiotic resistance.

We analyzed the whole-genome sequences of the hypermutable strains for mutations associated with specific antibiotic resistance mechanisms (Fig. 2). The genes encoding structural components and regulators of the four main efflux systems of P. aeruginosa were examined at a genetic level (Table S1). Mutations were found in the efflux regulator genes mexR, mexT, mexZ, and nfxB in most of the hypermutator strains, which may result in increased expression of MexAB-OprM, MexEF-OprN, MexXY-OprM, and MexCD-OprJ efflux pumps, respectively (44). Our study showed that all isolates with increased tobramycin MIC values had inactivating mutations within the MexXY-OprM repressor, mexZ. This was similar to results of a previous study, which found that 82% of multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa isolates overproduced MexXY-OprM (45). Additionally, CW19 had a nonsense mutation early in mexC that may have contributed to the susceptible phenotype to ciprofloxacin despite having an inactivating mutation in nfxB (negative regulator of the efflux pump MexCD-OprJ). CW44 had a one-nucleotide deletion in mexX, causing a frameshift that likely contributed to the measured low MIC to tobramycin. CW34 and CW35 had an identical deletion of one nucleotide in mexB, which resulted in a frameshift that likely contributed to the susceptibility to β-lactam antibiotics. However, expression levels of efflux pump components cannot be ascertained from this genomic data. Ultimately, transcriptomic analysis is required to elucidate the expression levels and full effect of these mutations.

FIG 2.

The mutations in the resistome (resistance-associated genes) examined via whole-genome sequencing and bioinformatics analysis for the 13 hypermutable P. aeruginosa clinical isolates from patients with cystic fibrosis and the well-characterized PAO1 wild-type strain. The strongest hypermutators for high rifampin mutation frequency (RIF MF) are shown in the darkest purple.

Resistance to β-lactams often results from the overproduction of the chromosomally encoded cephalosporinase AmpC, which results from mutations in the peptidoglycan-recycling genes, ampD, dacB, and ampR (46, 47). In two isolates, frameshift mutations were identified in ampR, encoding a regulator, and one isolate had a nonsense mutation in ampD (Table S1). Another gene that is involved in the recycling of cell wall components and has been found to increase expression of AmpC when mutated is mpl, which encodes UDP-N-acetylmuramate:L-alanyl-γ-d-glutamyl-meso-diaminopimelate ligase (48). Five isolates contained frameshift mutations in mpl, but reduced β-lactam susceptibilities did not always correspond with the presence of these mutations; validation through β-lactamase assays would be able to provide additional insight.

A link was apparent between reduced aztreonam susceptibility and the presence of missense mutations in ftsl, which encodes penicillin-binding protein 3 (PBP3); two ftsl mutations leading to the amino acid substitutions R504C and F533L in PBP3 have been previously described (49). We also examined the gene oprD, whose altered expression is responsible for reduced susceptibility to carbapenems (50). Eight of the isolates were found to have inactivating mutations in oprD, with four being found in strains with meropenem resistance (Table 1 and Table S1). One meropenem-intermediate resistant isolate also had a missense mutation in OprD that may have contributed to reduced meropenem susceptibility. The frameshift mutations in oprD observed for a number of hypermutators did not always lead to greatly reduced susceptibility; however, it has been suggested that reduced susceptibility requires multiple resistance mechanisms (45).

Fluoroquinolone resistance is usually associated with missense mutations in gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE, encoding fluoroquinolone targets (51, 52). Ten hypermutators were found to be ciprofloxacin resistant (Table 1); this was likely due to previously described mutations leading to missense substitutions in GyrA at residues 83 and 87 for most of the isolates (53, 54), while three hypermutator strains had mutations in gyrB, leading to previously described substitutions (Q467R and E468D) that are likely responsible for resistance (33, 54, 55). Aminoglycoside resistance can occur with missense mutations in elongation factor G (fusA1); previously described mutations in fusA1 (resulting in V93A, K504E, Y552C, and T671I substitutions) were found in all tobramycin-resistant hypermutators (Table S1) (33).

In conclusion, this study has for the first time determined the prevalence of P. aeruginosa hypermutators in adult patients with CF from a health care center in Australia and established that the majority of the hypermutator isolates come from divergent lineages, with a small number of very closely related pairs among them. Furthermore, mutations in mutL and mutS were determined to be the cause of the hypermutator phenotype in the majority of these isolates. Hypermutable isolates had a higher proportion with MDR and were more often resistant to each of the tested antibiotics in comparison to nonhypermutable isolates. These findings indicate that hypermutable P. aeruginosa isolates are playing an important role in the antibiotic resistance problem in patients with CF in Australia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and media.

We characterized 59 P. aeruginosa clinical isolates collected from the sputa of 37 consecutive patients with CF (in 2013) (Table 1). For 22 patients, a mucoid and nonmucoid colony variant was present from the same culture and one of each was selected for analysis. The P. aeruginosa PAO1 WT strain and the hypermutable PAOΔmutS strain (mutS knock out of PAO1) (9) were used as controls with these clinical isolates. All susceptibility studies and viable counting were performed on cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton agar (CAMHA; containing 25 mg/liter Ca2+ and 12.5 mg/liter Mg2+; Medium Preparation Unit, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, Australia). Drug-containing agar plates were prepared using CAMHA (BD, Sparks, MD) supplemented with the appropriate amount of antibiotic. The rifampin (Sigma-Aldrich, Sydney, Australia) stock solution was prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma-Aldrich, Sydney, Australia) and subsequently filter sterilized using a 0.22-μm polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) syringe filter (Merck Millipore, Cork, Ireland). The mucoid or nonmucoid phenotype of growth exhibited after 24 h of incubation at 37°C on antibiotic-free CAMHA of the 59 clinical isolates was recorded.

Mutation frequencies.

Rifampin (300 mg/liter) MF were determined as previously described (4). This determination was carried out in at least 4 experiments, and the average was used as the MF.

Antibiotic susceptibility.

The MICs of ceftazidime (test range, 0.016 to 256 mg/liter), ciprofloxacin (0.002 to 32 mg/liter), meropenem (0.002 to 32 mg/liter), aztreonam (0.016 to 256 mg/liter), and tobramycin (0.016 to 256 mg/liter) for each clinical isolate were determined using Etest strips (bioMérieux, North Ryde, Australia). The manufacturer’s protocol was followed with alterations as described previously (27), and readings were taken at 20, 24, 36, and 48 h for comparison. The MICs at 24 h were evaluated based on EUCAST susceptibility breakpoints (56) to determine which isolates had MDR (resistance to ≥1 agent from ≥3 different antimicrobial categories [35]).

Genetic basis for hypermutation.

Whole-genome sequencing was performed on all 13 hypermutators. Genomic DNA (gDNA) was purified from each hypermutable clinical isolate using the GenElute bacterial genomic DNA kit (NA2110-IKT; Sigma-Aldrich, Castle Hill, NSW, Australia) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, except that 40 μl of sterile distilled water was used instead of the elution solution. The gDNA was sequenced utilizing the paired-end 150-bp protocol on an Illumina NextSeq instrument at Micromon Next-Gen Sequencing Facility (Monash University, Clayton, VIC, Australia).

De novo assembly of the raw read data (average read depth of 39 to 51×) was performed using CLC Genomics Workbench v7.03 software. Automatic annotations of the de novo assemblies were produced using Rapid Annotations using Subsystem Technology (RAST) version2, accessed November 2016 (57).

To further explore the genetic basis of hypermutation, complementation studies were performed. Briefly, plasmids pUCPMS and pUCPML, harboring PAO1 wild-type mutS and mutL genes, and plasmid PUCP24, a control cloning vector, were used to transform the mutator isolates. Complementation was demonstrated by reversion of the increased MF for rifampin resistance in two independent transformant colonies for each hypermutator isolate.

Phylogenetic analysis.

The comparative phylogenetic analysis was performed on the de novo assembled genomes together with 63 publicly available P. aeruginosa genomes obtained from Pathosystems Resource Integration Centre (PATRIC) (58). The phylogenetic tree to determine evolutionary relatedness was created using Parsnp, a fast core genome multialigner software (Harvest) (59). Furthermore, an SNP analysis was performed via Nullarbor v1.01 (60).

Comparative genomic analysis.

The paired reads were reference assembled against PAO1 using CLC Genomics Workbench. The nucleic acid sequences were extracted for the MMR and other mutator-associated genes mutS, mutL, mutT, mutY, mutM, uvrD (mutU), radA, pfpI, sodM, oxyR, polA, ung, dnaQ (mutD), tRNAGly (PA2583, PA2819.1, and PA2819.2), mfd, and sodB; the mucoid phenotype genes mucA, algP, algU, and algD; the quorum sensing gene, lasR; and resistance-associated genes gyrA, gyrB, parC, parE, fusA1, galU, ampR, ampC, ampD, ftsI (PBP3), dacB, dacC, mpl, oprD, rpoB, phoP, phoQ, pmrA, pmrB, pagL, glpT, mexR, armR, mexA, mexB, nalC, nalD, mexZ, armZ, mexX, mexY, oprM, parR, parS, amgR, amgS, nfxB, mexC, mexD, oprJ, mexT, mexS, mexE, mexF, oprN, and oprF. These nucleic acid sequences were converted to amino acid sequences using the ExPasy online translational tool on the Bioinformatics Research Portal (Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics); subsequently, the amino acid sequences from each isolate were compared to that of PAO1 using the Clustal Omega multiple sequence alignment program (61–63). DNA sequence changes or predicted amino acid changes resulting from mutations were evaluated as evidence for loss of function.

Statistics.

A Mann-Whitney U test was used for the comparison of resistance rates, distributions of MICs, and mucoid reversion between hypermutators and nonhypermutators. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Where the sample size was less than 30, a Fisher exact test was used to refine the P value.

Data availability.

The Fastq files for each strain have been deposited in GenBank under BioProject accession number PRJNA510693.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Kate Rogers of the Centre for Medicine Use and Safety, Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Monash University.

Vanessa E. Rees is thankful to the Australian Government and Monash Graduate Education for providing the Australian Postgraduate Award and Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship. This work was supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) project grant APP1101553 (to Cornelia B. Landersdorfer, John D. Boyce, Jürgen B. Bulitta, Antonio Oliver, and Roger L. Nation). Cornelia B. Landersdorfer was supported by an Australian NHMRC Career Development Fellowship (APP1062509), and Anton Y. Peleg is the recipient of a NHMRC Practitioner Fellowship (APP1117940). Carla López-Causapé and Antonio Oliver are supported by the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad of Spain, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, cofinanced by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) “A way to achieve Europe”, through the Spanish Network for the Research in Infectious Diseases (grants RD12/0015 and RD16/0016).

Funders had no role in the study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

We have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.02538-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lyczak JB, Cannon CL, Pier GB. 2002. Lung infections associated with cystic fibrosis. Clin Microbiol Rev 15:194–222. doi: 10.1128/CMR.15.2.194-222.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kerem E, Corey M, Gold R, Levison H. 1990. Pulmonary function and clinical course in patients with cystic fibrosis after pulmonary colonization with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Pediatr 116:714–719. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(05)82653-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oliver A. 2010. Mutators in cystic fibrosis chronic lung infection: prevalence, mechanisms, and consequences for antimicrobial therapy. Int J Med Microbiol 300:563–572. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oliver A, Canton R, Campo P, Baquero F, Blazquez J. 2000. High frequency of hypermutable Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis lung infection. Science 288:1251–1254. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5469.1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oliver A, Mena A. 2010. Bacterial hypermutation in cystic fibrosis, not only for antibiotic resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect 16:798–808. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Macia MD, Blanquer D, Togores B, Sauleda J, Perez JL, Oliver A. 2005. Hypermutation is a key factor in development of multiple-antimicrobial resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains causing chronic lung infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 49:3382–3386. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.8.3382-3386.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferroni A, Guillemot D, Moumile K, Bernede C, Le Bourgeois M, Waernessyckle S, Descamps P, Sermet-Gaudelus I, Lenoir G, Berche P, Taddei F. 2009. Effect of mutator P. aeruginosa on antibiotic resistance acquisition and respiratory function in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol 44:820–825. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waine DJ, Honeybourne D, Smith EG, Whitehouse JL, Dowson CG. 2008. Association between hypermutator phenotype, clinical variables, mucoid phenotype, and antimicrobial resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Clin Microbiol 46:3491–3493. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00357-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mena A, Smith EE, Burns JL, Speert DP, Moskowitz SM, Perez JL, Oliver A. 2008. Genetic adaptation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to the airways of cystic fibrosis patients is catalyzed by hypermutation. J Bacteriol 190:7910–7917. doi: 10.1128/JB.01147-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Montanari S, Oliver A, Salerno P, Mena A, Bertoni G, Tummler B, Cariani L, Conese M, Doring G, Bragonzi A. 2007. Biological cost of hypermutation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains from patients with cystic fibrosis. Microbiol 153:1445–1454. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2006/003400-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oliver A, Baquero F, Blazquez J. 2002. The mismatch repair system (mutS, mutL and uvrD genes) in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: molecular characterization of naturally occurring mutants. Mol Microbiol 43:1641–1650. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mandsberg LF, Ciofu O, Kirkby N, Christiansen LE, Poulsen HE, Hoiby N. 2009. Antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains with increased mutation frequency due to inactivation of the DNA oxidative repair system. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53:2483–2491. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00428-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Govan JR, Deretic V. 1996. Microbial pathogenesis in cystic fibrosis: mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia cepacia. Microbiol Rev 60:539–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin DW, Schurr MJ, Mudd MH, Govan JR, Holloway BW, Deretic V. 1993. Mechanism of conversion to mucoidy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa infecting cystic fibrosis patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 90:8377–8381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith EE, Buckley DG, Wu Z, Saenphimmachak C, Hoffman LR, D'Argenio DA, Miller SI, Ramsey BW, Speert DP, Moskowitz SM, Burns JL, Kaul R, Olson MV. 2006. Genetic adaptation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa to the airways of cystic fibrosis patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:8487–8492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602138103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.D'Argenio DA, Wu M, Hoffman LR, Kulasekara HD, Deziel E, Smith EE, Nguyen H, Ernst RK, Larson Freeman TJ, Spencer DH, Brittnacher M, Hayden HS, Selgrade S, Klausen M, Goodlett DR, Burns JL, Ramsey BW, Miller SI. 2007. Growth phenotypes of Pseudomonas aeruginosa lasR mutants adapted to the airways of cystic fibrosis patients. Mol Microbiol 64:512–533. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05678.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoffman LR, Kulasekara HD, Emerson J, Houston LS, Burns JL, Ramsey BW, Miller SI. 2009. Pseudomonas aeruginosa lasR mutants are associated with cystic fibrosis lung disease progression. J Cyst Fibros 8:66–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luzar MA, Thomassen MJ, Montie TC. 1985. Flagella and motility alterations in Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains from patients with cystic fibrosis: relationship to patient clinical condition. Infect Immun 50:577–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahenthiralingam E, Campbell ME, Speert DP. 1994. Nonmotility and phagocytic resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from chronically colonized patients with cystic fibrosis. Infect Immun 62:596–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barth AL, Pitt TL. 1995. Auxotrophic variants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa are selected from prototrophic wild-type strains in respiratory infections in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Clin Microbiol 33:37–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lomovskaya O, Warren MS, Lee A, Galazzo J, Fronko R, Lee M, Blais J, Cho D, Chamberland S, Renau T, Leger R, Hecker S, Watkins W, Hoshino K, Ishida H, Lee VJ. 2001. Identification and characterization of inhibitors of multidrug resistance efflux pumps in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: novel agents for combination therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 45:105–116. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.1.105-116.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poole K, Srikumar R. 2001. Multidrug efflux in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: components, mechanisms and clinical significance. Curr Top Med Chem 1:59–71. doi: 10.2174/1568026013395605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nikaido H. 1994. Prevention of drug access to bacterial targets: permeability barriers and active efflux. Science 264:382–388. doi: 10.1126/science.8153625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Driscoll JA, Brody SL, Kollef MH. 2007. The epidemiology, pathogenesis and treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. Drugs 67:351–368. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200767030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blumberg PM, Strominger JL. 1974. Interaction of penicillin with the bacterial cell: penicillin-binding proteins and penicillin-sensitive enzymes. Bacteriol Rev 38:291–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.López-Causapé C, de Dios-Caballero J, Cobo M, Escribano A, Asensio Ó, Oliver A, Del Campo R, Cantón R, Solé A, Cortell I, Asensio O, García G, Martínez MT, Cols M, Salcedo A, Vázquez C, Baranda F, Girón R, Quintana E, Delgado I, de Miguel MÁ, García M, Oliva C, Prados MC, Barrio MI, Pastor MD, Olveira C, de Gracia J, Álvarez A, Escribano A, Castillo S, Figuerola J, Togores B, Oliver A, López C, de Dios Caballero J, Tato M, Máiz L, Suárez L, Cantón R. 2017. Antibiotic resistance and population structure of cystic fibrosis Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from a Spanish multi-centre study. Int J Antimicrob Agents 50:334–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2017.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Macia MD, Borrell N, Perez JL, Oliver A. 2004. Detection and susceptibility testing of hypermutable Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains with the Etest and disk diffusion. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 48:2665–2672. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.7.2665-2672.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ciofu O, Mandsberg LF, Bjarnsholt T, Wassermann T, Hoiby N. 2010. Genetic adaptation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa during chronic lung infection of patients with cystic fibrosis: strong and weak mutators with heterogeneous genetic backgrounds emerge in mucA and/or lasR mutants. Microbiology 156:1108–1119. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.033993-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marvig RL, Johansen HK, Molin S, Jelsbak L. 2013. Genome analysis of a transmissible lineage of Pseudomonas aeruginosa reveals pathoadaptive mutations and distinct evolutionary paths of hypermutators. PLoS Genet 9:e1003741. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lutz L, Leao RS, Ferreira AG, Pereira DC, Raupp C, Pitt T, Marques EA, Barth AL. 2013. Hypermutable Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis patients from two Brazilian cities. J Clin Microbiol 51:927–930. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02638-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feliziani S, Lujan AM, Moyano AJ, Sola C, Bocco JL, Montanaro P, Canigia LF, Argarana CE, Smania AM. 2010. Mucoidy, quorum sensing, mismatch repair and antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa from cystic fibrosis chronic airways infections. PLoS One 5:e12669. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kenna DT, Doherty CJ, Foweraker J, Macaskill L, Barcus VA, Govan JR. 2007. Hypermutability in environmental Pseudomonas aeruginosa and in populations causing pulmonary infection in individuals with cystic fibrosis. Microbiol 153:1852–1859. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2006/005082-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lopez-Causape C, Sommer LM, Cabot G, Rubio R, Ocampo-Sosa AA, Johansen HK, Figuerola J, Canton R, Kidd TJ, Molin S, Oliver A. 2017. Evolution of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutational resistome in an international cystic fibrosis clone. Sci Rep 7:5555. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05621-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith DJ, Ramsay KA, Yerkovich ST, Reid DW, Wainwright CE, Grimwood K, Bell SC, Kidd TJ. 2016. Pseudomonas aeruginosa antibiotic resistance in Australian cystic fibrosis centres. Respirology 21:329–337. doi: 10.1111/resp.12714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, Carmeli Y, Falagas ME, Giske CG, Harbarth S, Hindler JF, Kahlmeter G, Olsson-Liljequist B, Paterson DL, Rice LB, Stelling J, Struelens MJ, Vatopoulos A, Weber JT, Monnet DL. 2012. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect 18:268–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Naughton S, Parker D, Seemann T, Thomas T, Turnbull L, Rose B, Bye P, Cordwell S, Whitchurch C, Manos J. 2011. Pseudomonas aeruginosa AES-1 exhibits increased virulence gene expression during chronic infection of cystic fibrosis lung. PLoS One 6:e24526. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rau MH, Marvig RL, Ehrlich GD, Molin S, Jelsbak L. 2012. Deletion and acquisition of genomic content during early stage adaptation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to a human host environment. Environ Microbiol 14:2200–2211. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang L, Jelsbak L, Marvig RL, Damkiær S, Workman CT, Rau MH, Hansen SK, Folkesson A, Johansen HK, Ciofu O, Høiby N, Sommer MOA, Molin S. 2011. Evolutionary dynamics of bacteria in a human host environment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:7481–7486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018249108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miguel V, Correa EM, De Tullio L, Barra JL, Argarana CE, Villarreal MA. 2013. Analysis of the interaction interfaces of the N-terminal domain from Pseudomonas aeruginosa MutL. PLoS One 8:e69907. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ciofu O, Mandsberg LF, Wang H, Hoiby N. 2012. Phenotypes selected during chronic lung infection in cystic fibrosis patients: implications for the treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm infections. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 65:215–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2012.00983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boyce JR, Miller RV. 1982. Motility as a selective force in the reversion of cystic fibrosis-associated mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa to the nonmucoid phenotype in culture. Infect Immun 37:840–844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moyano AJ, Lujan AM, Argarana CE, Smania AM. 2007. MutS deficiency and activity of the error-prone DNA polymerase IV are crucial for determining mucA as the main target for mucoid conversion in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol 64:547–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lujan AM, Moyano AJ, Segura I, Argarana CE, Smania AM. 2007. Quorum-sensing-deficient (lasR) mutants emerge at high frequency from a Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutS strain. Microbiol 153:225–237. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.29021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Poole K. 2011. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: resistance to the max. Front Microbiol 2:65. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Henrichfreise B, Wiegand I, Pfister W, Wiedemann B. 2007. Resistance mechanisms of multiresistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains from Germany and correlation with hypermutation. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 51:4062–4070. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00148-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cabot G, Ocampo-Sosa AA, Tubau F, Macia MD, Rodríguez C, Moya B, Zamorano L, Suárez C, Peña C, Martínez-Martínez L, Oliver A. 2011. Overexpression of AmpC and efflux pumps in Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from bloodstream infections: prevalence and impact on resistance in a Spanish multicenter study. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:1906–1911. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01645-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moya B, Dotsch A, Juan C, Blazquez J, Zamorano L, Haussler S, Oliver A. 2009. Beta-lactam resistance response triggered by inactivation of a nonessential penicillin-binding protein. PLoS Pathog 5:e1000353. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tsutsumi Y, Tomita H, Tanimoto K. 2013. Identification of novel genes responsible for overexpression of ampC in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:5987–5993. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01291-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cabot G, Zamorano L, Moya B, Juan C, Navas A, Blazquez J, Oliver A. 2016. Evolution of Pseudomonas aeruginosa antimicrobial resistance and fitness under low and high mutation rates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:1767–1778. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02676-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pai H, Kim J, Kim J, Lee JH, Choe KW, Gotoh N. 2001. Carbapenem resistance mechanisms in Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 45:480–484. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.2.480-484.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wong A, Rodrigue N, Kassen R. 2012. Genomics of adaptation during experimental evolution of the opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS Genet 8:e1002928. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oh H, Stenhoff J, Jalal S, Wretlind B. 2003. Role of efflux pumps and mutations in genes for topoisomerases II and IV in fluoroquinolone-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains. Microb Drug Resist 9:323–328. doi: 10.1089/107662903322762743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cabot G, López-Causapé C, Ocampo-Sosa AA, Sommer LM, Domínguez MÁ, Zamorano L, Juan C, Tubau F, Rodríguez C, Moyà B, Peña C, Martínez-Martínez L, Plesiat P, Oliver A. 2016. Deciphering the resistome of the widespread Pseudomonas aeruginosa sequence type 175 international high-risk clone through whole-genome sequencing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:7415–7423. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01720-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kos VN, Deraspe M, McLaughlin RE, Whiteaker JD, Roy PH, Alm RA, Corbeil J, Gardner H. 2015. The resistome of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in relationship to phenotypic susceptibility. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:427–436. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03954-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bruchmann S, Dotsch A, Nouri B, Chaberny IF, Haussler S. 2013. Quantitative contributions of target alteration and decreased drug accumulation to Pseudomonas aeruginosa fluoroquinolone resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:1361–1368. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01581-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.EUCAST. 2017. The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing—EUCAST. http://www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints/.

- 57.Aziz RK, Bartels D, Best AA, DeJongh M, Disz T, Edwards RA, Formsma K, Gerdes S, Glass EM, Kubal M, Meyer F, Olsen GJ, Olson R, Osterman AL, Overbeek RA, McNeil LK, Paarmann D, Paczian T, Parrello B, Pusch GD, Reich C, Stevens R, Vassieva O, Vonstein V, Wilke A, Zagnitko O. 2008. The RAST Server: Rapid Annotations using Subsystems Technology. BMC Genomics 9:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wattam AR, Davis JJ, Assaf R, Boisvert S, Brettin T, Bun C, Conrad N, Dietrich EM, Disz T, Gabbard JL, Gerdes S, Henry CS, Kenyon RW, Machi D, Mao C, Nordberg EK, Olsen GJ, Murphy-Olson DE, Olson R, Overbeek R, Parrello B, Pusch GD, Shukla M, Vonstein V, Warren A, Xia F, Yoo H, Stevens RL. 2017. Improvements to PATRIC, the all-bacterial bioinformatics database and analysis resource center. Nucleic Acids Res 45:D535–d542. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Treangen TJ, Ondov BD, Koren S, Phillippy AM. 2014. The Harvest suite for rapid core-genome alignment and visualization of thousands of intraspecific microbial genomes. Genome Biol 15:524. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0524-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Seemann T, Kwong JC, de Silva AG, Dm B. 2015. Nullarbor. https://github.com/tseemann/nullarbor. Retrieved 5 June 2017.

- 61.Sievers F, Wilm A, Dineen D, Gibson TJ, Karplus K, Li W, Lopez R, McWilliam H, Remmert M, Soding J, Thompson JD, Higgins DG. 2011. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol Syst Biol 7:539. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li W, Cowley A, Uludag M, Gur T, McWilliam H, Squizzato S, Park YM, Buso N, Lopez R. 2015. The EMBL-EBI bioinformatics web and programmatic tools framework. Nucleic Acids Res 43:W580–W584. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McWilliam H, Li W, Uludag M, Squizzato S, Park YM, Buso N, Cowley AP, Lopez R. 2013. Analysis tool web services from the EMBL-EBI. Nucleic Acids Res 41:W597–W600. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The Fastq files for each strain have been deposited in GenBank under BioProject accession number PRJNA510693.