Staphylococcus aureus is a leading cause of infection in the United States, and due to the rapid development of resistance, new antibiotics are constantly needed. trans-Translation is a particularly promising antibiotic target because it is conserved in many bacterial species, is critical for bacterial survival, and is unique among prokaryotes.

KEYWORDS: LL-37, Staphylococcus aureus, trans-translation, cathelicidin, oxadiazoles

ABSTRACT

Staphylococcus aureus is a leading cause of infection in the United States, and due to the rapid development of resistance, new antibiotics are constantly needed. trans-Translation is a particularly promising antibiotic target because it is conserved in many bacterial species, is critical for bacterial survival, and is unique among prokaryotes. We have investigated the potential of KKL-40, a small-molecule inhibitor of trans-translation, and find that it inhibits both methicillin-susceptible and methicillin-resistant strains of S. aureus. KKL-40 is also effective against Gram-positive pathogens, including a vancomycin-resistant strain of Enterococcus faecalis, Bacillus subtilis, and Streptococcus pyogenes, although its performance with Gram-negative pathogens is mixed. KKL-40 synergistically interacts with the human antimicrobial peptide LL-37, a member of the cathelicidin family, to inhibit S. aureus but not other antibiotics tested, including daptomycin, kanamycin, or erythromycin. KKL-40 is not cytotoxic to HeLa cells at concentrations that are 100-fold higher than the effective MIC. We also find that S. aureus develops minimal resistance to KKL-40 even after multiday passage at sublethal concentrations. Therefore, trans-translation inhibitors could be a particularly promising drug target against S. aureus, not only because of their ability to inhibit bacterial growth but also because of their potential to simultaneously render S. aureus more susceptible to host antimicrobial peptides.

INTRODUCTION

Infections caused by Staphylococcus aureus, particularly strains resistant to existing antibiotics, pose a significant health care challenge. S. aureus infections are the leading cause of death by an infectious agent in the United States (1, 2). The direct costs of treating these infections are estimated at $478 million to $2.2 billion annually (3). S. aureus is notorious for its ability to develop antibiotic resistance, and new antibiotics must be continually developed to treat resistant strains (1, 2). Ribosome rescue is a potential target for new antibiotics. Ribosomes that translate to the 3′ end of an mRNA without terminating at a stop codon must be rescued, or the protein synthesis capacity will be lost and the bacteria will die (4). The predominant mechanism for ribosome rescue is trans-translation, a pathway in which the transfer-messenger RNA (tmRNA)-SmpB ribonucleoprotein complex tags the nascent polypeptide for proteolysis and releases the stalled ribosome at a stop codon within tmRNA. Genes encoding tmRNA and SmpB have been identified in >99% of bacterial species. In some species, these genes are essential, but other species can survive without them because they have an alternative ribosome rescue factor, such as ArfA or ArfB (4). S. aureus does not encode any of the known alternative ribosome rescue factors, and the ssrA (encoding tmRNA) and smpB genes have been scored as essential in saturating transposon mutagenesis screens (5, 6), suggesting that trans-translation is a particularly promising target.

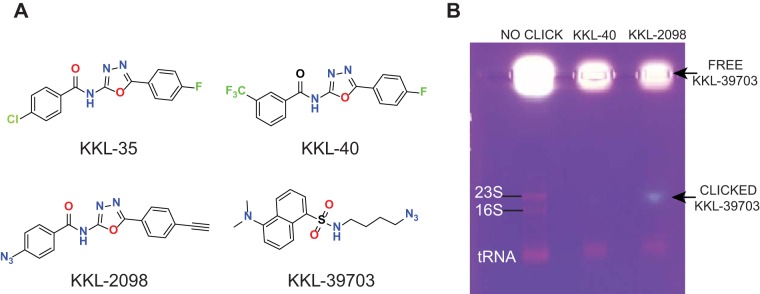

Small-molecule inhibitors of ribosome rescue were identified in a high-throughput screen. A family of oxadiazole benzamides, including KKL-35 and KKL-40 (Fig. 1), was shown to have potent antibiotic activity against Bacillus anthracis, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Francisella tularensis, Legionella pneumophila, and ΔtolC strains of Escherichia coli (7–10). Biochemical and cross-linking data indicated that KKL-35 and KKL-40 bind to a site on 23S rRNA that is not bound by other drugs, and this binding inhibits trans-translation but not translation (7, 8). Here, we show that these oxadiazole compounds inhibit the growth of S. aureus and act synergistically with the human antimicrobial peptide LL-37 in vitro. These results suggest that ribosome rescue inhibitors could be developed as antibiotics for treatment of S. aureus infections.

FIG 1.

Oxadiazole compounds target 23S rRNA in S. aureus. (A) Chemical structures of the oxadiazoles (KKL-35 and KKL-40), a photoreactive analog (KKL-2098), and the fluorescent reporter (KKL-39703) used in the click bioconjugation experiments. (B) Agarose gel analysis of the click conjugation reactions using total RNA preparations from S. aureus treated with either KKL-40 or KKL-2098. Click-conjugated KKL-39703 is indicated by the fluorescence band (arrow) comigrating with the 23S rRNA only in the KKL-2098-treated sample. Free, unreacted KKL-39703 remains in the wells. No click, total RNA plus KKL-39703 without reagents for the click reaction; KKL-40, total RNA from cells treated with KKL-40 (which will not cross-link) clicked with KKL-39703; KKL-2098, total RNA from cells treated with KKL-2098 clicked with KKL-39703.

RESULTS

Oxadiazoles target 23S rRNA in S. aureus.

A high-throughput screen to identify small-molecule inhibitors of trans-translation yielded several compounds, including the highly active oxadiazole derivatives KKL-35 and KKL-40 (Fig. 1) (8, 10). In vivo cross-linking experiments subsequently demonstrated that these oxadiazoles target 23S rRNA in E. coli and Mycobacterium smegmatis (7). To determine if the compounds have the same activity in S. aureus, we performed an intracellular photolabeling experiment using the cross-linkable oxadiazole derivative KKL-2098 (Fig. 1). A log-phase culture of S. aureus was divided and treated with either KKL-40, which will not cross-link, or KKL-2098. Cells were irradiated with UV light to activate the azide group of KKL-2098 and initiate cross-linking. The cells were lysed, total RNA was prepared, and the fluorescent reporter KKL-39703 was conjugated to the alkyne moiety of KKL-2098 using a click chemistry reaction (7). Agarose gel analysis showed a fluorescent band that comigrated with 23S rRNA from samples treated with KKL-2098, but this band was absent in the control samples treated with KKL-40 (Fig. 1). These observations were in accord with those of E. coli and M. smegmatis (7), suggesting that the 23S rRNA target for these oxadiazoles is conserved in S. aureus.

trans-Translation inhibitors are effective against S. aureus and other Gram-positive bacteria.

Broth microdilution assays showed that both KKL-35 and KKL-40 effectively inhibit several strains of S. aureus, including strain Newman, a methicillin-susceptible strain that has been used extensively in studying S. aureus pathogenesis (11); MRSA252, a globally prevalent genetically diverse health care-associated methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) strain (12); and USA300, the predominant community-associated MRSA strain in the United States (2) (Fig. 2). There were slight differences in susceptibility, with USA300 being the most sensitive, with an MIC of 0.64 μg/ml (KKL-35) or 0.35 μg/ml (KKL-40), while Newman and MRSA252 had the same MIC of 1.28 μg/ml (KKL-35) or 0.7 μg/ml (KKL-40). It should be noted that 2-fold differences in MIC values are within the intrinsic error of the assay method, so these slight differences in MICs between strains may not be biologically significant. Because KKL-40 is slightly more effective, with MIC values that are half those of KKL-35, we chose to focus on KKL-40. In 10% serum, KKL-40 activity was inhibited, and the effective MIC increased to 11.23 μg/ml for S. aureus Newman (data not shown). This is in line with results of previous studies (10) but means that either KKL-40 would be limited to a topical antibiotic or oxadiazole derivatives with lower serum binding would need to be developed.

FIG 2.

Oxadiazole compounds prevent the growth of Staphylococcus aureus strains. Shown are data for growth of the Newman, MRSA252, and USA300 strains of S. aureus overnight in the presence of KKL-35 (A) and KKL-40 (B) at the indicated concentrations. Results from 3 independent experiments are presented as means ± standard deviations (SD). Statistically significant differences from the medium-alone control are presented (*, P < 0.05; ****, P < 0.0001 [as determined by one-way analysis of variance [ANOVA] followed by Dunnett’s multiple-comparison test]).

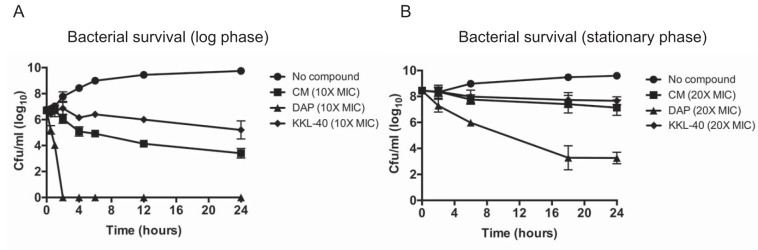

We next looked at the method by which KKL-40 inhibits S. aureus and compared it to those of known bactericidal (daptomycin) and bacteriostatic (chloramphenicol) antibiotics. Cultures of S. aureus grown overnight were diluted 1:10,000 and grown for 3 h (log phase) or 7 h (early stationary phase) before antibiotics were added at 10× or 20× their MICs. In both cases, KKL-40 inhibited the growth of S. aureus in a manner similar to that of chloramphenicol, with very little change from the starting amount, even though numbers of bacteria in untreated cultures increased by 3 logs (log phase) or 1 log (stationary phase), but it had no bactericidal activity after 24 h (Fig. 3A and B).

FIG 3.

KKL-40 acts in a bacteriostatic manner. Log-phase (A) or stationary-phase (B) S. aureus Newman cultures were incubated with KKL-40, daptomycin (DAP), and chloramphenicol (CM) at 10× or 20× their MICs. Surviving CFU per milliliter were enumerated at the indicated time points. Results from 3 independent experiments are presented as means ± SD.

In addition to S. aureus, KKL-40 was effective against other Gram-positive species, including Enterococcus faecalis, Streptococcus pyogenes, and Bacillus subtilis (Table 1). Our results with Gram-negative species were mixed. Although we saw activity against several species, including Haemophilus influenzae, Yersinia pestis, Burkholderia mallei, and Burkholderia pseudomallei, no effective MIC was seen at concentrations of up to 22 μg/ml of KKL-40 against Escherichia coli K-12, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, or Acinetobacter baumannii (Table 1). MICs were observed using the E. coli ΔtolC and lptD4213 mutants, which have defects in efflux and permeability of the outer membrane (13, 14), suggesting that the KKL-40 target is present in E. coli but that KKL-40 cannot accumulate in wild-type cells.

TABLE 1.

KKL-40 activity

| Species and/or strain | Resistancea | KKL-40 MIC (μg/ml) |

|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus aureus Newman | 0.7 | |

| Staphylococcus aureus USA300 | CA-MRSA | 0.35 |

| Staphylococcus aureus MRSA252 | HA-MRSA | 0.7 |

| Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 51299 | VRE | 1.4 |

| Streptococcus pyogenes M1 5488 | 2.8 | |

| Bacillus subtilis PY79 | 0.7 | |

| Haemophilus influenzae | 0.1 | |

| Yersinia pestis | 2.3 | |

| Burkholderia mallei | 1.1 | |

| Burkholderia pseudomallei | 2.3 | |

| Escherichia coli K-12 MG1655 | >22 | |

| Escherichia coli lptD4213 | 0.3 | |

| Escherichia coli ΔtolC | 0.3 | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14 | >22 | |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 13883 | >22 | |

| Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC 19609 | >22 |

CA-MRSA, community-associated MRSA; HA-MRSA, hospital-associated MRSA; VRE, vancomycin-resistant enterococci.

KKL-40 synergizes with antimicrobial peptides.

In addition to being required for viability in several bacterial species, loss of trans-translation leads to increased susceptibility to various stressors, including antibiotics, as well as decreased virulence in bacterial pathogens (4, 15). Therefore, inhibiting trans-translation not only may inhibit bacterial growth but also could increase susceptibility to host defenses and/or antibiotic treatment. To test this, we performed checkerboard analysis (16), where S. aureus Newman was simultaneously treated with 2-fold serial dilutions of the human antimicrobial peptide LL-37, a member of the cathelicidin family of antimicrobial peptides, and KKL-40, arranged in a two-dimensional array. The fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) index was calculated (Table 2) based on the MIC of the antimicrobials alone and in combination (Table 3), and synergistic inhibition of S. aureus growth was seen with cotreatment with LL-37 and KKL-40. We next tried the same assay with the antibiotics daptomycin, kanamycin, and erythromycin. Daptomycin has characteristics similar to those of LL-37, including targeting the bacterial membrane (17), while previous studies have seen an increase in sensitivity to antibiotics, including aminoglycosides, such as kanamycin, and macrolides, such as erythromycin, when components of trans-translation are missing (18–21). However, none of these antibiotics exhibited a synergistic interaction with KKL-40 in S. aureus using the checkerboard assay (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Interactions with KKL-40

| Bacterial species | Antibiotic A | Antibiotic B | FICA index | FICB index | FICA+B index | Synergistic interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus (Newman) | LL-37 | KKL-40 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.5 | Yes |

| S. aureus (Newman) | Daptomycin | KKL-40 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | No |

| S. aureus (Newman) | Kanamycin | KKL-40 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | No |

| S. aureus (Newman) | Erythromycin | KKL-40 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | No |

| E. coli K-12 | Polymyxin B | KKL-40 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.375 | Yes |

TABLE 3.

MICs from synergistic checkerboard assays

| Bacterial species | Assay medium | Antimicrobial | MICalone (μg/ml) | MICcombo (μg/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus (Newman) | RPMI + 5% LB | LL-37 | >36 | 18 |

| KKL-40 | 2.8 | 0.7 | ||

| E. coli K-12 | CA-MHBII | Polymyxin B | 0.6 | 0.15 |

| KKL-40 | >11.2 | 2.8 | ||

KKL-40 was not effective against many of the Gram-negative species that we tested, including E. coli. However, MICs were observed using the E. coli ΔtolC and lptD4213 mutants, which have defects in efflux and permeability of the outer membrane (13, 14). Polymyxin B is a nonribosomal peptide antibiotic that kills Gram-negative bacteria through interaction with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and disruption of the outer membrane (22). We hypothesized that combining polymyxin B and KKL-40 may increase the effectiveness of KKL-40 against Gram-negative pathogens, as the permeabilization of the outer membrane by polymyxin B would allow KKL-40 to enter the cell. The FIC index was again calculated based on the MIC of the antimicrobials alone and in combination, and synergistic inhibition between KKL-40 and polymyxin was seen (Tables 2 and 3).

KKL-40 is not toxic to human cells and has a low level of resistance development.

Next, we looked at whether KKL-40 is selectively toxic to bacterial cells by examining its effect on human cells. We incubated KKL-40 with human HeLa cells, a cervical cancer cell line, for 24 h in serum-free medium. We found that KKL-40 is not toxic to human HeLa cells, even at a concentration of 70 μg/ml, which is 100-fold higher than the effective MIC (Fig. 4).

FIG 4.

KKL-40 does not exhibit cytotoxicity to mammalian cells. HeLa cells were incubated with KKL-40 at the indicated concentrations for 24 h, and percent cell survival was then calculated. Results from 3 independent experiments are presented as means ± SD. ID50, 50% infective dose.

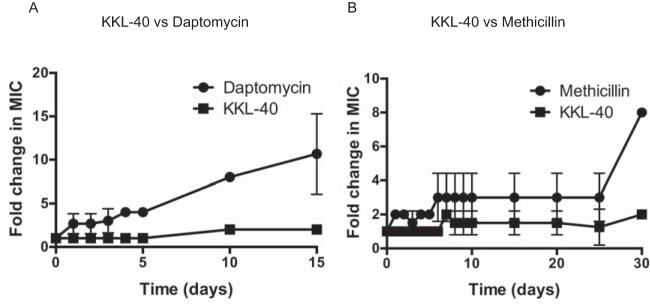

One challenge with all antibiotics is the eventual generation of resistance, and this is particularly an issue with S. aureus (1, 2). In order to determine how quickly S. aureus becomes resistant to KKL-40, we passaged S. aureus serially for up to 30 days with sublethal concentrations of KKL-40 along with sublethal concentrations of either methicillin or daptomycin as a comparison. There was at least an 8-fold change in the effective MIC for both daptomycin and methicillin by days 15 and 30, respectively, whereas only a 2-fold change in MIC was seen for KKL-40 in the same amount of time (Fig. 5).

FIG 5.

S. aureus develops minimal resistance to KKL-40. S. aureus Newman was consecutively incubated for 24 h with sublethal concentrations of KKL-40 and daptomycin (A) or methicillin (B), and MIC assays were performed at the indicated days to calculate the fold increase in the MIC relative to the original starting MIC. Results from two (methicillin) or three (daptomycin) independent experiments are presented as means ± SD.

DISCUSSION

KKL-35 and KKL-40 inhibit the growth of methicillin-susceptible as well as both community- and hospital-associated MRSA strains at relatively low concentrations, indicating the importance of trans-translation for maintaining the viability of S. aureus. This is consistent with the findings of saturating transposon mutagenesis studies, where no transposon insertion was found in the genes encoding tmRNA or SmpB, indicating that these genes may be required for viability (5, 6). KKL-40 is bacteriostatic and inhibited the growth of both log- and early-stationary-phase S. aureus. In addition to S. aureus, we find that KKL-40 is effective against several other Gram-positive pathogens, including a vancomycin-resistant strain of Enterococcus faecalis, Bacillus subtilis, and Streptococcus pyogenes. Although activity has been seen against Gram-negative species, including Shigella flexneri, F. tularensis, and L. pneumophila (8, 9), as well as H. influenzae, Y. pestis, B. mallei, and B. pseudomallei in this study, we saw little to no activity against E. coli, P. aeruginosa, K. pneumoniae, or A. baumannii. However, KKL-40 potently inhibited the growth of two mutant E. coli strains that have increased permeability, and coincubation of KKL-40 with polymyxin B, which disrupts the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria (22), lowered the effective MIC of KKL-40 in a synergistic manner. This suggests that KKL-40 activity in E. coli is limited more by permeability across the outer membrane than by target availability in the cell. The outer membranes of Gram-negative bacteria differ in permeability due to differences in porins as well as differences in the chemical structure of LPS (23). It is therefore possible that differences in Gram-negative susceptibility to KKL-40 could be due to differences in outer membrane permeability. While it is likely that KKL-40 will be effective against a wide range of Gram-positive species, Gram-negative species would need to be evaluated on a case-by-case basis.

In addition to acting as a potent antimicrobial on its own, KKL-40 has a synergistic interaction with the human antimicrobial peptide LL-37. The increased effectiveness of KKL-40 in the presence of LL-37 is likely due to membrane damage caused by even sublethal levels of LL-37, which leads to an increased ability of KKL-40 to permeate the cell and increased efficacy at lower concentrations. It is also possible that the inhibition of trans-translation causes a maladapted stress response to LL-37, leading to increased susceptibility. Regardless of the exact mechanism, these results further highlight the potential effectiveness of trans-translation inhibition. Not only are these compounds effective in their own right, they also could increase bacterial susceptibility to host antimicrobial peptides. Furthermore, these compounds are nontoxic in a variety of mammalian cells, including HeLa cells in this study as well as macrophages and a human liver cell line, HepG2 (10). Finally, generation of resistance against KKL-40 is limited, even in S. aureus, a pathogen notorious for its ability to acquire antibiotic resistance (1, 2). These results are consistent with those seen in L. pneumophila, E. coli, and S. flexneri, where no resistance to KKL-35 was generated (8, 9). Developing resistance to KKL-40 may be more difficult because mutations that prevent binding to the ribosome are lethal, because mutations would be required in all rRNA genes, or because there is a second, unidentified target for KKL-40. The latter possibility seems unlikely, however, because overexpression of ribosome rescue factors in other bacteria decreases the activity of KKL-40 (10), consistent with ribosome rescue being the target responsible for activity. Unfortunately, KKL-40 is inhibited in the presence of serum, so while it could be used as a topical antibiotic, further development of oxadiazole derivatives with better clinical properties would be needed for more-widespread use. However, given the effectiveness of the KKL compounds against a variety of pathogens, the limited cytotoxicity, and the low propensity for resistance, our results argue for the continued development of inhibitors targeting trans-translation as potentially highly effective antibiotics.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media, and antibiotics.

S. aureus strains (Newman, MRSA252, and USA300) and E. faecalis ATCC 51299 were grown in tryptic soy broth (TSB; Hardy Diagnostics). A. baumannii ATCC 19609, P. aeruginosa PA14, and B. subtilis PY79 were grown in brain heart infusion (BHI) medium (Hardy Diagnostics). E. coli strains and P. aeruginosa PA14 were grown in Luria broth (LB; Hardy Diagnostics). K. pneumoniae ATCC 13883 and S. pyogenes M1 5488 were grown in Todd-Hewitt broth (THB; Fluka). Burkholderia species, Y. pestis, and H. influenzae were grown in Mueller-Hinton II broth (BD) with calcium to a final concentration of 50 μg/ml to make CA-MHBII. All antibiotics were acquired from Sigma, except for daptomycin (Cubist Pharmaceuticals) and LL-37 (Anaspec).

Bioorthogonal photoaffinity labeling and click conjugation.

Intracellular photolabeling was performed by adding either KKL-40 or KKL-2098 at 0.02 μg/ml to mid-exponential-phase cultures of S. aureus. These cultures were grown for 1 h, and cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in a phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution (1.2 g/liter Na2HPO4, 0.22 g/liter NaH2PO4, 8.5 g/liter NaCl [pH 7.5]). Intracellular photoaffinity labeling and click conjugation reactions were performed as previously described (7), with the exception that in this study, KKL-39703 was used as the fluorescent reporter.

Synthesis.

KKL-35, KKL-40, and KKL-2098 were synthesized as previously reported (7, 10). For N-(4-azidobutyl)-5-(dimethylamino)naphthalene-1-sulfonamide (KKL-39703), dansyl chloride (400 mg; 1.5 mmol) dissolved in 2 ml dichloromethane (DCM) was added dropwise to a round-bottomed flask containing a solution of 4-bromo-1-aminobutane (419 mg; 1.8 mmol) and trimethylamine (453 mg; 4.44 mmol) in 8 ml DCM chilled at 0°C (under an inert atmosphere). This reaction mixture was allowed to warm up gradually to room temperature, and the reaction was then left to proceed for 16 h. The reaction was terminated when thin-layer chromatography (TLC) analysis indicated complete consumption of dansyl chloride. The volatile solvents were evaporated under reduced pressure, and the crude product was purified by flash chromatography over a silica gel eluting with a mixture of 20% ethyl acetate in hexanes, to give the product as a bright-yellow oil (451 mg; 96.7% yield). 1H NMR (nuclear magnetic resonance) (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.59 (m, 2H), 1.64 (m, 2H), 2.93 (s, 6H), 2.96 (q, 2H, J = 6.3 Hz), 3.22 (t, 2H, J = 6.3 Hz), 4.82 (t, 1H, J = 4.9 Hz), 7.17 (d, 1H, J = 7.3 Hz), 7.54 (m, 2H), 8.24 (m, 2H), 8.53 (d, 1H, J = 8.5 Hz). ESI (electrospray ionization) (positive) m/z; [M + H]+calculated for C16, H21, N5, O2, S, 348.1; observed, 348.1.

MIC assays.

Cultures grown overnight were diluted and grown to early log phase at an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.4. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines were followed, including using at least 5 × 105 CFU/ml in the appropriate medium and subculture volume (24). To facilitate comparisons with daptomycin and polymyxin B, CA-MHBII was used for all assays, with the exceptions that RPMI plus 5% LB was used for assays with LL-37 and THB was used for Streptococcus pyogenes. Fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco) was used for assays including serum. All assays were carried out in 96-well plates in a total volume of 200 μl. After 16 to 20 h of incubation at 37°C under static conditions, the OD600 was read, and the MIC was defined as the lowest concentration of antibiotic with no visible growth. All MIC assays were repeated at least 2 times.

Time-dependent killing.

S. aureus Newman cultures grown overnight were diluted 1:10,000 into CA-MHBII and grown for 3 h (log phase) or approximately 7 h (early stationary phase with an OD of at least 0.8) at 37°C with shaking. Log- or stationary-phase cultures were then aliquoted into separate culture tubes (2 ml each), antibiotics were added at 10× their MICs (KKL-40, 7 μg/ml; daptomycin, 10 μg/ml; chloramphenicol, 80 μg/ml) or 20× their MICs (KKL-40, 14 μg/ml; daptomycin, 20 μg/ml; chloramphenicol, 160 μg/ml), and culture tubes were incubated at 37°C with shaking for an additional 24 h. At the indicated time points, 100 μl of culture from each tube was removed, centrifuged, and resuspended in an equivalent volume of PBS, and 10-fold dilutions were then plated to enumerate surviving CFU per milliliter.

Synergy assays.

The checkerboard method was used to determine the MICs for each antibiotic alone and in combination. Both KKL-40 and the paired antimicrobial were 2-fold serially diluted, and 50 μl containing 4 times the final concentration of both antibiotics was then added to each well, with the final well containing no antibiotic. KKL-40 was added across the columns, and the other antibiotic was added down the rows, resulting in a checkerboard of doubly increasing concentrations of KKL-40 and the paired antibiotic. RPMI plus 5% LB was used for assay mixtures containing LL-37, CA-MHBII was used for all others, and final antibiotic concentrations were 36 μg/ml to 2.25 μg/ml for LL-37, 2 μg/ml to 0.0625 μg/ml for daptomycin, 2 μg/ml to 0.0625 μg/ml for erythromycin, 16 μg/ml to 0.5 μg/ml for kanamycin, and 2.4 μg/ml to 0.0375 μg/ml for polymyxin B. KKL-40 concentrations for S. aureus were 5.6 μg/ml to 0.176 μg/ml for assays with RPMI plus 5% LB and 1.4 μg/ml to 0.044 μg/ml for assays with CA-MHBII, while KKL-40 concentrations for E. coli were 11.23 μg/ml to 0.7 μg/ml. Bacterial cultures were grown to log phase (OD of 0.4) in TSB (S. aureus Newman) or LB (E. coli), washed, and diluted 1:150 in the corresponding medium, and 100 μl was added per well for a final volume of 200 μl/well. Plates were incubated at 37°C under static conditions, and the OD was read 22 to 24 h later. The FIC of each antibiotic was determined, where FICA is the MIC of antibiotic A in the combination/MIC of antibiotic A alone (FICA = MICA+B/MICA) and FICB is the MIC of antibiotic B in the combination/MIC of antibiotic B alone (FICB = MICB+A/MICB). The FIC index was calculated by adding FICA and FICB. When the highest concentration of antibiotic used was not inhibitory (for example, 36 μg/ml LL-37 with S. aureus or 11.2 μg/ml KKL-40 with E. coli), 2 times the highest concentration was used in the FIC calculation (i.e. 72 μg/ml for LL-37 alone and 22.46 μg/ml for KKL-40 alone). A synergistic interaction is defined by an FIC index of ≤0.5, no interaction is defined by an FIC index of >0.5 to 4, and an antagonistic interaction is defined by an FIC index of >4.0 (16). All assays were repeated at least 3 independent times.

Mammalian cell cytotoxicity.

HeLa cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Gibco) with 10% FBS (Gibco), 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Difco) and 1% l-glutamine (HyClone). Cells were plated at 2 × 104 cells per well in 96-well plates and incubated for 24 h at 37°C with 5% CO2. Medium was then removed, cells were washed once in PBS, and serum-free DMEM containing serially diluted KKL-40 at the indicated concentrations was added to the cells. Cytotoxicity was assessed 24 h after incubation with the compounds by adding 20 μl of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium (MTS) from the CellTiter 96 AQueous nonradioactive cell proliferation assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI) directly to the culture wells, incubating the mixture for 2 h at 37°C with 5% CO2, and recording the absorbance at 490 nm. One hundred percent viability was set at the absorbance of the untreated cells, and percent HeLa cell survival was calculated by dividing the OD of KKL-40-treated cells by the OD of untreated cells and multiplying this value by 100.

Generation of resistance.

Cells were passaged at 24-h intervals in the presence of sublethal concentrations of methicillin (2 μg/ml), daptomycin (0.5 μg/ml), or KKL-40 (0.35 μg/ml) (approximately 0.5-fold the original effective MIC). In the experiments comparing methicillin and KKL-40, TSB was used for culture medium and MIC assays, and in the experiments comparing daptomycin and KKL-40, CA-MHBII was used for culture medium and MIC assays. MIC assays were conducted at days 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30. Bacteria were first diluted to an OD600 of ∼0.7 and then diluted 1:400 in medium (TSB or CA-MHBII), and MIC assays were performed as described above. Data are plotted as fold changes from the original MICs, which were 4 μg/ml for methicillin, 1 μg/ml for daptomycin, and 0.7 μg/ml for KKL-40.

Statistics.

All statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH grants Al111692 and GM12165 to K.C.K. and a grant from the TCU Research and Creative Activities Fund to S.M.M.

REFERENCES

- 1.Otto M. 2012. MRSA virulence and spread. Cell Microbiol 14:1513–1521. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2012.01832.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeLeo FR, Chambers HF. 2009. Reemergence of antibiotic-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the genomics era. J Clin Invest 119:2464–2474. doi: 10.1172/JCI38226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee BY, Singh A, David MZ, Bartsch SM, Slayton RB, Huang SS, Zimmer SM, Potter MA, Macal CM, Lauderdale DS, Miller LG, Daum RS. 2013. The economic burden of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA). Clin Microbiol Infect 19:528–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03914.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keiler KC. 2015. Mechanisms of ribosome rescue in bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol 13:285–297. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaudhuri RR, Allen AG, Owen PJ, Shalom G, Stone K, Harrison M, Burgis TA, Lockyer M, Garcia-Lara J, Foster SJ, Pleasance SJ, Peters SE, Maskell DJ, Charles IG. 2009. Comprehensive identification of essential Staphylococcus aureus genes using transposon-mediated differential hybridisation (TMDH). BMC Genomics 10:291. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fey PD, Endres JL, Yajjala VK, Widhelm TJ, Boissy RJ, Bose JL, Bayles KW. 2013. A genetic resource for rapid and comprehensive phenotype screening of nonessential Staphylococcus aureus genes. mBio 4:e00537-12. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00537-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alumasa JN, Manzanillo PS, Peterson ND, Lundrigan T, Baughn AD, Cox JS, Keiler KC. 2017. Ribosome rescue inhibitors kill actively growing and nonreplicating persister Mycobacterium tuberculosis cells. ACS Infect Dis 3:634–644. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.7b00028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramadoss NS, Alumasa JN, Cheng L, Wang Y, Li S, Chambers BS, Chang H, Chatterjee AK, Brinker A, Engels IH, Keiler KC. 2013. Small molecule inhibitors of trans-translation have broad-spectrum antibiotic activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:10282–10287. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1302816110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brunel R, Descours G, Durieux I, Doublet P, Jarraud S, Charpentier X. 2018. KKL-35 exhibits potent antibiotic activity against Legionella species independently of trans-translation inhibition. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 62:e01459-17. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01459-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goralski TD, Dewan KK, Alumasa JN, Avanzato V, Place DE, Markley RL, Katkere B, Rabadi SM, Bakshi CS, Keiler KC, Kirimanjeswara GS. 2016. Inhibitors of ribosome rescue arrest growth of Francisella tularensis at all stages of intracellular replication. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:3276–3282. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03089-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baba T, Bae T, Schneewind O, Takeuchi F, Hiramatsu K. 2008. Genome sequence of Staphylococcus aureus strain Newman and comparative analysis of staphylococcal genomes: polymorphism and evolution of two major pathogenicity islands. J Bacteriol 190:300–310. doi: 10.1128/JB.01000-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holden MT, Feil EJ, Lindsay JA, Peacock SJ, Day NP, Enright MC, Foster TJ, Moore CE, Hurst L, Atkin R, Barron A, Bason N, Bentley SD, Chillingworth C, Chillingworth T, Churcher C, Clark L, Corton C, Cronin A, Doggett J, Dowd L, Feltwell T, Hance Z, Harris B, Hauser H, Holroyd S, Jagels K, James KD, Lennard N, Line A, Mayes R, Moule S, Mungall K, Ormond D, Quail MA, Rabbinowitsch E, Rutherford K, Sanders M, Sharp S, Simmonds M, Stevens K, Whitehead S, Barrell BG, Spratt BG, Parkhill J. 2004. Complete genomes of two clinical Staphylococcus aureus strains: evidence for the rapid evolution of virulence and drug resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:9786–9791. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402521101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zgurskaya HI, Krishnamoorthy G, Ntreh A, Lu S. 2011. Mechanism and function of the outer membrane channel TolC in multidrug resistance and physiology of enterobacteria. Front Microbiol 2:189. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sampson BA, Misra R, Benson SA. 1989. Identification and characterization of a new gene of Escherichia coli K-12 involved in outer membrane permeability. Genetics 122:491–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keiler KC. 2008. Biology of trans-translation. Annu Rev Microbiol 62:133–151. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.162948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Odds FC. 2003. Synergy, antagonism, and what the chequerboard puts between them. J Antimicrob Chemother 52:1. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mishra NN, McKinnell J, Yeaman MR, Rubio A, Nast CC, Chen L, Kreiswirth BN, Bayer AS. 2011. In vitro cross-resistance to daptomycin and host defense cationic antimicrobial peptides in clinical methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:4012–4018. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00223-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abo T, Ueda K, Sunohara T, Ogawa K, Aiba H. 2002. SsrA-mediated protein tagging in the presence of miscoding drugs and its physiological role in Escherichia coli. Genes Cells 7:629–638. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2002.00549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luidalepp H, Hallier M, Felden B, Tenson T. 2005. tmRNA decreases the bactericidal activity of aminoglycosides and the susceptibility to inhibitors of cell wall synthesis. RNA Biol 2:70–74. doi: 10.4161/rna.2.2.2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li J, Ji L, Shi W, Xie J, Zhang Y. 2013. trans-Translation mediates tolerance to multiple antibiotics and stresses in Escherichia coli. J Antimicrob Chemother 68:2477–2481. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brunel R, Charpentier X. 2016. trans-Translation is essential in the human pathogen Legionella pneumophila. Sci Rep 6:37935. doi: 10.1038/srep37935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Velkov T, Roberts KD, Nation RL, Thompson PE, Li J. 2013. Pharmacology of polymyxins: new insights into an ‘old’ class of antibiotics. Future Microbiol 8:711–724. doi: 10.2217/fmb.13.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zgurskaya HI, Löpez CA, Gnanakaran S. 2015. Permeability barrier of Gram-negative cell envelopes and approaches to bypass it. ACS Infect Dis 1:512–522. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.5b00097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wiegand I, Hilpert K, Hancock RE. 2008. Agar and broth dilution methods to determine the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of antimicrobial substances. Nat Protoc 3:163–175. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]