Abstract

Aims

Estimating survival is challenging in the terminal phase of advanced heart failure. Patients, families, and health‐care organizations would benefit from more reliable prognostic tools. The Palliative Performance Scale Version 2 (PPSv2) is a reliable and validated tool used to measure functional performance; higher scores indicate higher functionality. It has been widely used to estimate survival in patients with cancer but rarely used in patients with heart failure. The aim of this study was to identify prognostic cut‐points of the PPSv2 for predicting survival among patients with heart failure receiving home hospice care.

Methods and results

This retrospective cohort study included 1114 adult patients with a primary diagnosis of heart failure from a not‐for‐profit hospice agency between January 2013 and May 2017. The primary outcome was survival time. A Cox proportional‐hazards model and sensitivity analyses were used to examine the association between PPSv2 scores and survival time, controlling for demographic and clinical variables. Receiver operating characteristic curves were plotted to quantify the diagnostic performance of PPSv2 scores by survival time. Lower PPSv2 scores on admission to hospice were associated with decreased median (interquartile range, IQR) survival time [PPSv2 10 = 2 IQR: 1–5 days; PPSv2 20 = 3 IQR: 2–8 days] IQR: 55–207. The discrimination of the PPSv2 at baseline for predicting death was highest at 7 days [area under the curve (AUC) = 0.802], followed by an AUC of 0.774 at 14 days, an AUC of 0.736 at 30 days, and an AUC of 0.705 at 90 days.

Conclusions

The PPSv2 tool can be used by health‐care providers for prognostication of hospice‐enrolled patients with heart failure who are at high risk of near‐term death. It has the greatest utility in patients who have the most functional impairment.

Keywords: Hospice, Palliative care, Heart failure, Prognosis, Palliative performance scale, End‐of‐life care

Introduction

Heart failure is a progressive disease characterized by high symptom burden that primarily affects older adults with multiple co‐morbid conditions.1 In the terminal phase (Stage D), estimating survival is challenging because it has a non‐linear disease trajectory.2, 3 As such, less than half of physicians accurately estimate survival,4 and the error is systematically optimistic.5

Although national guidelines recommend using population‐based risk calculators6, 7, 8 to estimate survival for patients with heart failure,8, 9 these models have limited ability to prospectively identify the vast majority of heart failure patients who will die in the next year.2, 10 Prognostication is thus hampered by limited tools, wide variation in time to death between patients,2 and poor accuracy of clinician‐derived survival estimates,4, 5 thus adversely affecting patient quality of life near the end of life.5

For patients and families, knowing how much time remains is important for decision‐making, closure for personal and family matters, and shared decision‐making focused on patient goals of care.2 A clear prognosis is also informative for hospice organizations who need to allocate end‐of‐life services and select therapies most consistent with a patient's estimated survival time. To handle the high symptom burden at the end of life, an intensification of services is often necessary. Given the high error in survival estimates for patients with heart failure,4, 5 having objective data demonstrating a high risk of mortality within a specified time frame would be informative for patients, patient families, and hospice agencies alike.

Palliative Performance Scale Version 2 (PPSv2) has been widely utilized across palliative care patient populations, yet limited data are available on its prognostic value in patients with heart failure. The PPSv2 is a modified version of the Karnofsky performance scale and is used to measure functional status in palliative care11, 12 and predict survival among terminally ill patients.13 Two systematic literature reviews report that the PPSv2 is highly predictive of survival in mixed palliative care populations.14, 15, 16 The relationship between a lower PPSv2 score and shorter length of survival has been reported most commonly for patients with cancer.17 To our knowledge, this is the first study to use the PPSv2 to estimate survival time among home hospice heart failure patients. The purpose of this study is to identify prognostic cut‐points of the PPSv2 for predicting survival among patients with heart failure receiving home hospice care.

Methods

Study setting and data sources

This retrospective cohort study included 1114 adult patients with a primary diagnosis of heart failure served from a not‐for‐profit hospice agency in New York between January 2013 and May 2017. This home hospice agency has an average daily census of >1000 patients in its hospice programme across all five New York City boroughs. The inclusion criterion for this study was patients with a primary diagnosis of heart failure over 18 years of age. For patients with multiple episodes of hospice care during the study period (i.e. two or more admissions), the first episode was selected. The sample included patients with complete data on all study measures.

Patient data were obtained from the electronic medical record database. This database has a diverse set of variables that includes socio‐demographics, severity of illness, co‐morbid conditions, admission disposition, PPSv2 scores that were collected by nurses at the time of enrolment, and date of death or discharge from hospice services. For patients who enrolled in and out of hospice on multiple occasions, we included the first episode of hospice care only. The home hospice agency and Columbia University Medical Center institutional review boards approved the conduct of this study, and the study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines for the reporting of observational studies were followed.18

Measures

The primary outcome in our study was survival time. This variable was calculated as the difference in days between the date of hospice admission and the date of death in hospice. Socio‐demographic characteristics included sex, age, race/ethnicity, insurance, marital status, the absence of a primary caregiver, and the absence of a health‐care proxy. International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision, Clinical Modification and 10th revision codes were used to calculate Charlson Comorbidity Index scores.19 Hospice referral source, which distinguished those who entered hospice following a hospitalization vs. non‐hospital settings, was also collected.

The PPSv2 is a reliable and validated tool used to measure functional performance across five domains: ambulation, activity and evidence of disease, independence in self‐care, oral intake, and level of consciousness13, 20 (Table 1). The PPSv2 is divided into 11 categories between 0% and 100% in 10% increments, in which higher scores indicate higher functionality.13 Because PPSv2 scores ranged from 0 to 60 in this cohort, we used six discrete PPS scores (10, 20, 30, 40, 50, and 60). For all patients of the Visiting Nurse Service of New York hospice programme, the PPSv2 is completed as part of a comprehensive admission assessment at admission to hospice care and then every 2 months as a measure of functional status and ongoing change.

Table 1.

Palliative Performance Scale Version 2 (PPSv2)

| PPS level, % | Ambulation | Activity and evidence of disease | Self‐care | Intake | Conscious level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | Full |

Normal activity and work No evidence of disease |

Full | Normal | Full |

| 90 | Full |

Normal activity and work No evidence of disease |

Full | Normal | Full |

| 80 | Full |

Normal activity and work No evidence of disease |

Full | Normal or reduced | Full |

| 70 | Reduced |

Unable normal job/work Significant disease |

Full | Normal or reduced | Full |

| 60 | Reduced |

Unable hobby/house work Significant disease |

Occasional assistance necessary | Normal or reduced |

Full or Confusion |

| 50 | Mainly sit/lie |

Unable to do any work Extensive disease |

Considerable assistance required | Normal or reduced |

Full or Confusion |

| 40 | Mainly in bed |

Unable to do most activity Extensive disease |

Mainly assistance | Minimal to sips |

Full or Drowsy +/− Confusion |

| 30 | Totally bed bound |

Unable to do any activity Extensive disease |

Total care | Mouth care only |

Full or Drowsy +/− Confusion |

| 20 | Totally bed bound |

Unable to do any activity Extensive disease |

Total care |

Full or Drowsy +/− Confusion |

|

| 10 | Totally bed bound |

Unable to do any activity Extensive disease |

Total care |

Drowsy or Coma +/− Confusion |

|

| 0 | Death | — | — | — | — |

Data analysis

Means and percentages were used to describe the study population, including demographic and clinical characteristics, and crude mortality rates by PPSv2 score. Medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) were used to describe survival time by PPSv2 score (among patients who died in hospice), and differences in survival by the PPSv2 were evaluated using the Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test. Receiver operating characteristic curves were plotted for all patients to quantify the diagnostic performance of PPSv2 scores. Sensitivity analyses were also conducted to examine whether diagnostic performance of PPSv2 scores varied by survival time. A Cox proportional‐hazards model was used to examine associations of survival time with PPSv2 scores, controlling for patient socio‐demographic and clinical characteristics.21 Patients who were discharged alive from hospice were censored at the date of discharge. A P‐value of 0.05 represented the threshold for determining statistical significance. Survival time was top coded to 1 year and censored as of the date of discharge if patients left hospice prior to their death. The Kaplan–Meier event‐free survival graphs controlled for all covariates in the regression model. All analyses were performed using R Version 3.4.3.

Results

Study population

The majority of home hospice patients in our analysis were female (56.6%) with a mean age of 86 years and had a primary caregiver (83.8%) (Table 2). All patients lived in New York City and were racially and ethnically diverse (22.4% Hispanic, 17.8% African American, and 7.6% Asian). Most patients were insured through Medicare (63.4%) or Managed Medicare (e.g. Medicare Advantage; 29.4%) and were admitted into hospice from the hospital (53.6%). PPSv2 scores at admission to hospice ranged from 10 to 60. The modal PPSv2 score was 40 (36.2% of all patients). The mean Charlson Comorbidity Index score was relatively low (2.8, SD = 1.1). The five most frequent co‐morbidities among patients included renal failure (25.0%), Type II diabetes without clinical complications (20.4%), chronic pulmonary disease (18.8%), dementia (16.1%), and stroke (9.5%). While the majority of patients died while under hospice care (72.3%), over a quarter of patients were discharged alive (27.7%). Among those who were discharged alive (n = 309), the reasons for discharge included acute hospitalization (49.5%), elective revocation to pursue disease‐directed treatments (21.0%), disqualification (16.2%), or transfer to another hospice or care setting (13.3%). There was minimal missing data (<5%) for all study measures.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the study population by the Palliative Performance Scale Version 2 (PPSv2) at admission

| Characteristics | Total | 10% | 20% | 30% | 40% | 50% | 60% | P‐value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of participants (%) | 1114 (100) | 82 (7) | 79 (7) | 288 (26) | 403 (36) | 243 (22) | 19 (2) | |

| Female sex | 630 (57) | 40 (49) | 44 (56) | 190 (66) | 224 (56) | 126 (52) | 6 (32) | 0.001 |

| Age (years) | ||||||||

| 18 to 64 | 48 (4) | 5 (6) | 5 (6) | 4 (1) | 15 (3.7) | 17 (7) | 2 (11) | <0.001 |

| 65 to 74 | 107 (10) | 17 (21) | 6 (8) | 22 (8) | 30 (7) | 27 (11) | 5 (26) | |

| 75 to 84 | 248 (22) | 23 (28) | 21 (27) | 53 (18) | 88 (22) | 57 (24) | 6 (32) | |

| 85+ | 711 (64) | 37 (45) | 47 (60) | 209 (73) | 270 (67) | 142 (58) | 6 (32) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.162 | |||||||

| Hispanic | 250 (22) | 20 (24) | 17 (22) | 55 (19) | 96 (24) | 57 (24) | 5 (26) | |

| Non‐Hispanic Black | 198 (18) | 11 (13) | 13 (17) | 44 (15) | 68 (17) | 56 (23) | 6 (32) | |

| Non‐Hispanic White | 581 (52) | 45 (55) | 45 (57) | 160 (56) | 211 (52) | 115 (47) | 5 (26) | |

| Other | 85 (8) | 6 (7) | 4 (5) | 29 (10) | 28 (7) | 15 (6) | 3 (16) | |

| Marital status | 0.176 | |||||||

| Not married | 756 (68) | 48 (59) | 50 (63) | 210 (73) | 269 (67) | 166 (68) | 13 (68) | |

| Married | 358 (32) | 34 (41) | 29 (37) | 78 (27) | 134 (33) | 77 (32) | 6 (32) | |

| Primary caregiver (none) | 181 (16) | 10 (12) | 19 (24) | 52 (18) | 55 (14) | 42 (17) | 3 (16) | 0.188 |

| Advanced directives (none) | 196 (18) | 23 (28) | 28 (35) | 49 (17) | 64 (16) | 26 (11) | 6 (32) | <0.001 |

| Payer source | 0.356 | |||||||

| Commercial/other | 44 (4) | 5 (6) | 4 (5) | 4 (1) | 19 (5) | 10 (4) | 1 (5) | |

| Managed Medicaid | 16 (1) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 4 (1) | 6 (2) | 1 (5) | |

| Managed Medicare | 327 (29) | 27 (33) | 21 (27) | 91 (32) | 114 (28) | 71 (29) | 4 (21) | |

| Medicaid | 21 (2) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 12 (3) | 4 (2) | 1 (5) | |

| Medicare | 706 (63) | 47 (57) | 52 (66) | 189 (66) | 254 (63) | 152 (63) | 12 (63) | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Score, mean (SD) | 2.82 (1) | 2.63 (1) | 2.82 (1) | 2.90 (1) | 2.83 (1) | 2.83 (1) | 2.32 (1) | 0.198 |

| Co‐morbidities, mean % | ||||||||

| Renal failure | 278 (25) | 16 (20) | 27 (34) | 60 (21) | 103 (26) | 68 (28) | 4 (21) | 0.1 |

| Type II diabetes | 227 (20) | 12 (15) | 11 (14) | 52 (18) | 97 (24) | 50 (21) | 5 (26) | 0.119 |

| Pulmonary disease | 209 (19) | 4 (5) | 12 (15) | 54 (19) | 80 (20) | 55 (23) | 4 (21) | 0.022 |

| Dementia | 179 (16) | 10 (12) | 15 (19) | 62 (22) | 59 (15) | 33 (14) | 0 (0) | 0.02 |

| Stroke | 106 (10) | 12 (15) | 9 (11) | 29 (10) | 36 (9) | 18 (7) | 2 (11) | 0.445 |

| Referral source | <0.001 | |||||||

| Hospital | 597 (54) | 70 (85) | 59 (75) | 150 (52) | 190 (47) | 116 (48) | 12 (63) | |

| Other setting | 517 (46) | 12 (15) | 20 (25) | 138 (48) | 213 (53) | 127 (52) | 7 (37) | |

| Discharge reason | <0.001 | |||||||

| Acute hospitalization | 153 (14) | 1 (1) | 2 (3) | 23 (8) | 69 (17) | 53 (22) | 5 (26) | |

| Disqualification | 50 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 9 (3) | 23 (6) | 16 (7) | 2 (11) | |

| Revocation | 65 (6) | 2 (2) | 3 (4) | 9 (3) | 26 (6) | 22 (9) | 3 (16) | |

| Transfer | 41 (4) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 6 (2) | 18 (4) | 14 (6) | 2 (11) | |

| Death | 805 (72) | 79 (96) | 73 (92) | 241 (84) | 267 (66) | 138 (57) | 7 (37) |

Percentage of hospice deaths and survival time by palliative performance scale score

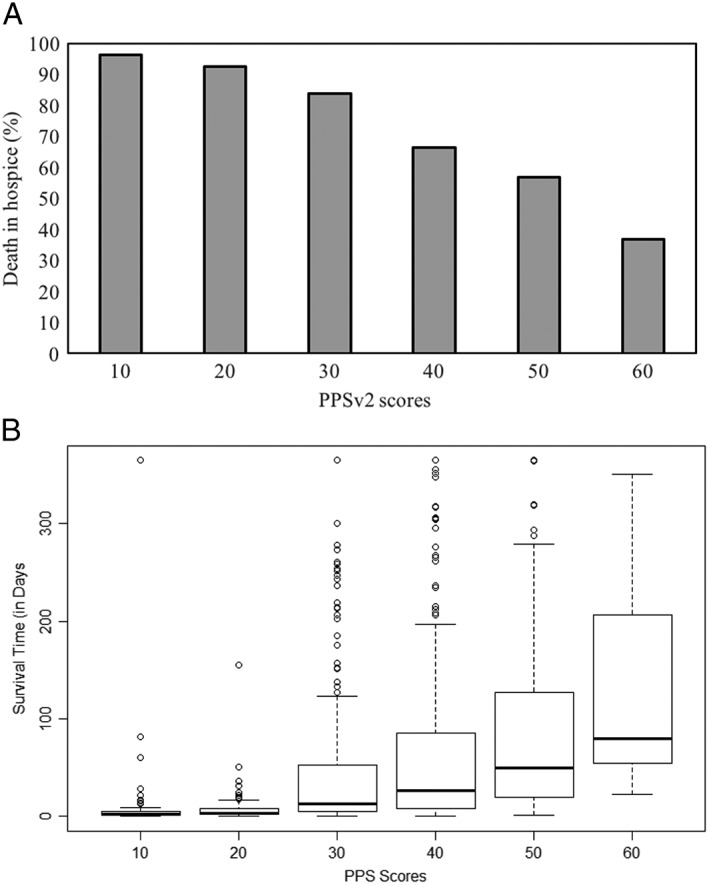

There was a higher mortality rate among patients admitted to hospice with low PPSv2 scores. Nearly all patients admitted to hospice with a PPSv2 score of 10 or 20 died during their hospice stay (96% and 92%, respectively). In contrast, a smaller percentage of those admitted with PPSv2 scores of 50 or 60 died in hospice (56% and 37%, respectively) (Figure 1A ).

Figure 1.

(A) Death in hospice by Palliative Performance Scale Version 2 (PPSv2) scores. It represents the proportion of people who died in hospice by PPSv2 score at admission to hospice. (B) Length of survival in days by PPSv2 scores. It represents a box plot of the median length of survival in days by PPSv2 score at admission to hospice.

The median survival time was significantly shorter for patients with lower PPSv2 scores compared with those with higher PPSv2 scores at the time of admission (P < 0.001). Among the 805 patients who died in hospice, the median survival time was 2 IQR: 1–5 and 3 IQR: 2–8 days for patients admitted with a PPSv2 score of 10 and 20, compared with a median survival time of 80 IQR: 55–207 days for patients with a PPSv2 score of 60 (Figure 1B ).

Accuracy of Palliative Performance Scale Version 2 scores at admission in predicting hospice survival

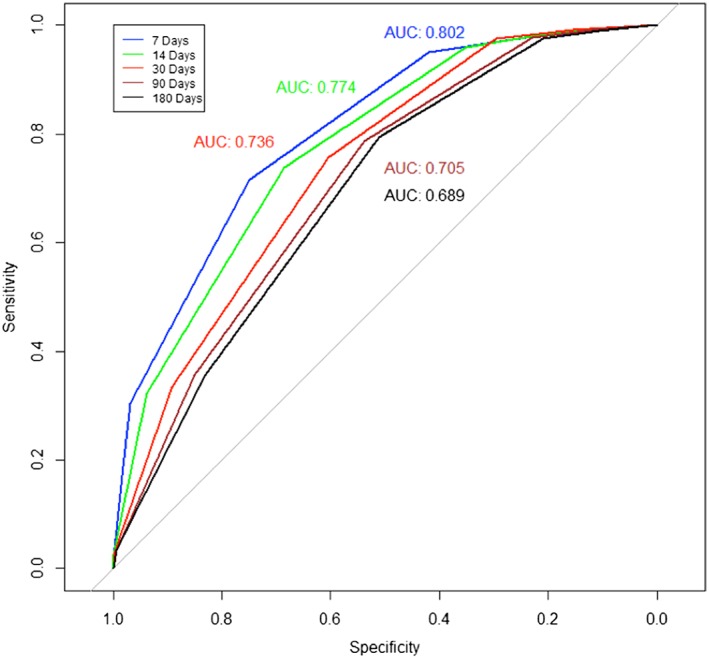

While the overall predictive accuracy of the PPSv2 for our sample was modest [area under the curve (AUC) = 0.69], the predictive accuracy of PPSv2 scores varied according to survival time. The PPSv2 had greater accuracy in predicting survival within the first weeks of hospice enrolment (AUC for hospice survival at 7 days = 0.80; 14 days = 0.77; 30 days = 0.74; 90 days = 0.71; 180 days = 0.69) (Figure 2 ).

Figure 2.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve by length of service group. It displays the ROC curve predicting survival based on Palliative Performance Scale Version 2 score values measured on hospice admission across five groups (i.e. 7, 14, 30, 90, and 180 days). AUC, area under the curve.

Factors predicting hospice survival time from a multivariable Cox proportional‐hazards model

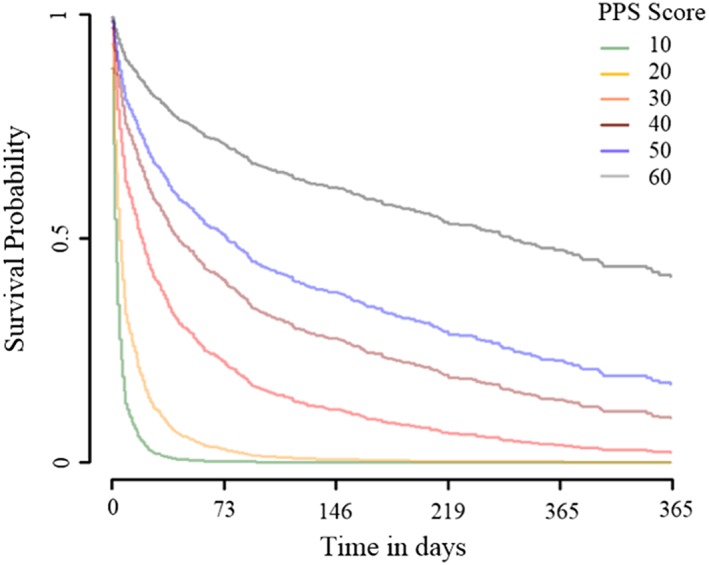

Results from the multivariate Cox proportional‐hazards regression predicting hospice survival time model indicate that PPSv2 scores on admission independently predict survival time among hospice patients with heart failure. Compared with those with a PPSv2 score of 60, those with PPSv2 scores ≤20 had particularly higher hazard of mortality: 18.6 (95% confidence interval = 8.5 to 40.7) and 10.2 (95% confidence interval = 4.6 to 22.6) among hospice patients with PPSv2 scores of 10 and 20, respectively (Table 3). Kaplan–Meier survival curves plotted for each value of the PPSv2 using Cox regression estimates and average covariate values indicate a graded increase in mortality risk from higher to lower PPSv2 scores (Figure 3 ).

Table 3.

Cox proportional‐hazards model predicting hazard of mortality among hospice patients with heart failure (N = 1114)

| Variable |

Unadjusted HR (95% CI) |

P‐value |

Adjusted HR (95% CI) |

P‐value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPSv2 10% | 16.48 (7.59–35.80) | <0.001 | 18.57 (8.47–40.72) | <0.001 |

| PPSv2 20% | 11.05 (5.08–24.07) | <0.001 | 10.20 (4.61–22.57) | <0.001 |

| PPSv2 30% | 3.89 (1.84–8.26) | <0.001 | 4.18 (1.94–9.01) | <0.001 |

| PPSv2 40% | 2.51 (1.19–5.32) | 0.02 | 2.65 (1.24–5.69) | 0.01 |

| PPSv2 50% | 1.77 (0.83–3.78) | 0.14 | 1.90 (0.88–4.10) | 0.10 |

| PPSv2 60% | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Age | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.58 | 1.00 (0.98–1.00) | 0.01 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 1.03 (0.90–1.19) | 0.66 | 1.16 (1.00–1.37) | 0.07 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| African American | 0.60 (0.50–0.74) | <0.001 | 0.53 (0.43–0.66) | <0.001 |

| Hispanic | 0.72 (0.60–0.87) | <0.001 | 0.60 (0.49–0.73) | <0.001 |

| Other | 0.79 (0.61–1.04) | 0.08 | 0.72 (0.55–0.95) | 0.02 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Not married | 0.86 (0.74–1.00) | 0.04 | 0.82 (0.70–0.98) | 0.03 |

| Primary caregiver | ||||

| Yes | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

| No | 1.20 (0.99–1.46) | 0.07 | 1.41 (1.16–1.72) | <0.001 |

| Advance directive | ||||

| No | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Yes | 2.18 (1.81–2.62) | <0.001 | 2.07 (1.70–2.52) | <0.001 |

| Referral source | ||||

| Hospital | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Other setting | 0.80 (0.69–0.91) | 0.001 | 0.84 (0.72–0.98) | 0.02 |

| Payer source | ||||

| Medicare | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Commercial/other | 0.869 (0.59–1.28) | 0.48 | 0.829 (0.55–1.25) | 0.37 |

| Managed Medicaid | 0.633 (0.30–1.34) | 0.23 | 0.613 (0.28–1.30) | 0.22 |

| Managed Medicare | 0.968 (0.83–1.13) | 0.68 | 1.059 (0.90–1.25) | 0.50 |

| Medicaid | 0.596 (0.33–1.08) | 0.09 | 0.384 (0.21–0.72) | 0.002 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Score | 0.925 (0.87–0.99) | 0.02 | 0.937 (0.88–0.10) | 0.05 |

CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; PPSv2, Palliative Performance Scale Version 2.

Figure 3.

Adjusted Kaplan–Meier survival curves from multiple Cox regression. It displays adjusted Kaplan–Meier survival curves plotted for each value of the Palliative Performance Scale Version 2 (PPSv2) using Cox regression estimates and average covariate values.

Discussion

This is one of the largest and most recent studies in the USA to evaluate the use of the PPSv2 for end‐of‐life prognostication among patients enrolled in hospice services with a primary diagnosis of heart failure. We found that the PPSv2 can be used to predict survival time for patients with heart failure who are enrolled in hospice. Predictive accuracy for death of the PPSv2 was incrementally improved among patient groups with low PPSv2 scores.

The PPSv2 is widely used in other patient populations for end‐of‐life prognostication, but there is limited research establishing its utility in the heart failure population. The findings of this study support the use of the PPSv2 score at admission for estimating survival in the first 30 days of hospice enrolment. The diagnostic accuracy was greatest among those with low scores, specifically scores of 10 and 20, which correlated with a survival of under a week. This finding is consistent with Harrold et al. who reported that, among a heterogeneous cohort of patients enrolled in a community hospice programme, PPSv2 scores are most accurate in predicting mortality within 1 week (AUC: 0.8~0.85).22 As such, the PPSv2 can be informative for patients and families who ask health‐care providers to predict anticipated life expectancy. Given the poor accuracy of clinician‐derived survival estimates,4, 5 the PPSv2 can be used as supporting evidence and a ‘reality check’ for the prognosis. The PPSv2 can also be used by hospice agencies to support the allocation of appropriate resources, such as more extensive symptom management support, to individuals for whom death is imminent.

This is the largest study of patients with heart failure to report Kaplan–Meier survival curves by initial PPSv2 scores among cardiac home hospice patients. In this sample, there were distinct survival curves for each discrete value of the PPSv2 (10, 20, 30, 40, 50, and 60). Our findings extend observations by Lau et al.23 and Downing et al.14 who similarly demonstrated that survival curves differed according to PPSv2 scores among a range of non‐heart failure diagnoses. Given that the association between PPSv2 scores and survival may vary between different patient populations, our study has established normative survival data for patients with heart failure. This is critical for building an evidence‐base that can be applied to patients with similar diagnoses and socio‐demographic characteristics.23 Finally, there are mixed perspectives on whether the PPSv2 score should be used as categorical24, 25 (i.e. groups of PPSv2 scores) or discrete (i.e. individual PPSv2 score values) variables for prognostication.16, 26, 27 Our study demonstrates that each PPSv2 score has a unique trajectory of survival time and supports the value of reporting individual discrete scores.

Patients with advanced heart failure often experience uncontrolled symptoms and rapid changes in their disease trajectories. Despite this, palliative care for patients with heart failure often lags behind that for other diseases such as cancer.28 Consistent with an American Heart Association guideline,2 we recommend that palliative approaches occur earlier in the disease process, ideally timing conversations about advance care planning between patients and providers with the initial diagnosis of heart failure.29, 30 Given the potential for improved prognostication and low burden on providers, our study findings indicate that there may be utility in using PPSv2 scores at hospice admission. Future research steps include the evaluation of the PPSv2 as part of informing hospice eligibility at the time of hospital discharge. Finally, almost a quarter of the population dis‐enrolled from hospice. This is a large and important segment of the population. Future research should explore predictors of discharge in this population, including PPSv2 scores. More research is also needed on the clinical utility of repeated PPSv2 measurements and whether they can be used to evaluate trajectories of change for patients. The clinical implication of this finding for health‐care providers within cardiac home hospice programmes is that this short, provider completed questionnaire can be a helpful indicator of survival in the next 30 days, which can be extremely valuable information for patients, families, and providers.

Limitations

There are some important limitations to consider. First, survival time is limited to the period of time that patients were enrolled in hospice and does not include data for patients who were discharged from hospice and admitted to local hospitals. We had limited data on patient socio‐economic status including income and education. Another limitation is that co‐morbid conditions may be underreported in this sample. Medicare regulations changed in 2014, implemented in 2015, mandating that hospices code for both the terminal illness and other coexisting diagnoses that support the terminal condition. These regulations may lead to an underreporting of co‐morbid conditions, which may explain why the Charlson Comorbidity Index is relatively low in this sample of patients. Very few participants in our sample had PPS scores of 60 raising questions about the validity of prognostication for scores in this range. This was also expected because it is a cohort of hospice‐enrolled patients. Finally, our data were derived from a single non‐profit hospice agency, albeit one that is located in a highly urban and culturally diverse setting.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrates that the PPSv2 at admission to hospice has high predictive accuracy for survival in the first 30 days among patients with heart failure, with incremental value at lower PPSv2 scores. These findings provide evidence that this tool can be used to estimate time to death among heart failure patients enrolled in hospice, which may be helpful for patients and families who frequently request accurate predictions of prognosis and for hospice agencies who may benefit from utilizing these data to better identify patients that require intensification of their services.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Eugenie and Joseph Doyle Research Partnership Fund from the Center for Home Care Policy and Research at the Visiting Nurse Service of New York and the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health for providing funding for R.M.C. under award number R00NR016275 and for D.B. under award number T32NR007969.

Masterson Creber R., Russell D., Dooley F., Jordan L., Baik D., Goyal P., Hummel S., Hummel E. K., and Bowles K. H. (2019) Use of the Palliative Performance Scale to estimate survival among home hospice patients with heart failure, ESC Heart Failure, 6, 371–378. 10.1002/ehf2.12398.

References

- 1. Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, Chiuve SE, Cushman M, Delling FN, Deo R, de Ferranti SD, Ferguson JF, Fornage M, Gillespie C, Isasi CR, Jiménez MC, Jordan LC, Judd SE, Lackland D, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth L, Liu S, Longenecker CT, Lutsey PL, Mackey JS, Matchar DB, Matsushita K, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, O'Flaherty M, Palaniappan LP, Pandey A, Pandey DK, Reeves MJ, Ritchey MD, Rodriguez CJ, Roth GA, Rosamond WD, Sampson UKA, Satou GM, Shah SH, Spartano NL, Tirschwell DL, Tsao CW, Voeks JH, Willey JZ, Wilkins JT, Wu JH, Alger HM, Wong SS, Muntner P, American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee . Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2018 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2018; 137: e67–e492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Allen LA, Stevenson LW, Grady KL, Goldstein NE, Matlock DD, Arnold RM, Cook NR, Felker GM, Francis GS, Hauptman PJ, Havranek EP, Krumholz HM, Mancini D, Riegel B, Spertus JA, American Heart Association , Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research , Council on Cardiovascular Nursing , Council on Clinical Cardiology , Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention , Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia . Decision making in advanced heart failure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2012; 125: 1928–1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gott M, Barnes S, Parker C, Payne S, Seamark D, Gariballa S, Small N. Dying trajectories in heart failure. Palliat Med 2007; 21: 95–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Warraich HJ, Allen LA, Mukamal KJ, Ship A, Kociol RD. Accuracy of physician prognosis in heart failure and lung cancer: comparison between physician estimates and model predicted survival. Palliat Med 2016; 30: 684–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Christakis NA, EB L. Extent and determinants of error in doctors' prognoses in terminally ill patients: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2000; 320: 469–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Levy WC, Mozaffarian D, Linker DT, Sutradhar SC, Anker SD, Cropp AB, Anand I, Maggioni A, Burton P, Sullivan MD, Pitt B, Poole‐Wilson PA, Mann DL, Packer M. The Seattle Heart Failure Model: prediction of survival in heart failure. Circulation 2006; 113: 1424–1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. May HT, Horne BD, Levy WC, Kfoury AG, Rasmusson KD, Linker DT, Mozaffarian D, Anderson JL, Renlund DG. Validation of the Seattle Heart Failure Model in a community‐based heart failure population and enhancement by adding B‐type natriuretic peptide. Am J Cardiol 2007; 100: 697–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pocock SJ, Ariti CA, McMurray JJ, Maggioni A, Køber L, Squire IB, Swedberg K, Dobson J, Poppe KK, Whalley GA, Doughty RN, Meta‐Analysis Global Group in Chronic Heart Failure . Predicting survival in heart failure: a risk score based on 39 372 patients from 30 studies. Eur Heart J 2013; 34: 1404–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Alba AC, Agoritsas T, Jankowski M, Courvoisier D, Walter SD, Guyatt GH, Ross HJ. Risk prediction models for mortality in ambulatory patients with heart failure: a systematic review. Circ Heart Fail 2013; 6: 881–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Allen LA, Matlock DD, Shetterly SM, Xu S, Levy WC, Portalupi LB, McIlvennan CK, Gurwitz JH, Johnson ES, Smith DH, Magid DJ. Use of risk models to predict death in the next year among individual ambulatory patients with heart failure. JAMA Cardiol 2017; 2: 435–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jansen WJJ, Buma S, Gootjes JRG, Zuurmond WWA, Perez RSGM, Loer SA. The palliative performance scale applied in high‐care residential hospice: a retrospective study. J Palliat Med 2015; 18: 67–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Simmons CPL, McMillan DC, McWilliams K, Sande TA, Fearon KC, Tuck S, Fallon MT, Laird BJ. Prognostic tools in patients with advanced cancer: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017; 53: 962–970.e910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Anderson F, Downing GM, Hill J, Casorso L, Lerch N. Palliative performance scale (PPS): a new tool. J Palliat Care 1996; 12: 5–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Downing M, Lau F, Lesperance M, Karlson N, Shaw J, Kuziemsky C, Bernard S, Hanson L, Olajide L, Head B, Ritchie C, Harrold J, Casarett D. Meta‐analysis of survival prediction with palliative performance scale. J Palliat Care 2007; 23: 245–252; discussion 252‐244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Baik D, Russell D, Jordan L, Dooley F, Bowles K, Masterson Creber R. Using the palliative performance scale to estimate survival for patients at the end of life: a systematic review of the literature. J Palliat Med 2018; 21: 1651–1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Downing GM, Lesperance M, Lau F, Yang J. Survival implications of sudden functional decline as a sentinel event using the palliative performance scale. J Palliat Med 2010; 13: 549–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Weng LC, Huang HL, Wilkie DJ, Hoenig NA, Suarez ML, Marschke M, Durham J. Predicting survival with the palliative performance scale in a minority‐serving hospice and palliative care program. J Pain Symptom Manage 2009; 37: 642–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med 2007; 147: 573–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, Fong A, Burnand B, Luthi JC, Saunders LD, Beck CA, Feasby TE, Ghali WA. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD‐9‐CM and ICD‐10 administrative data. Med Care 2005; 43: 1130–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ho F, Lau F, Downing MG, Lesperance M. A reliability and validity study of the palliative performance scale. BMC Palliat Care 2018; 7: 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cox D. Regression models and life‐tables. J R Stat Soc B Methodol 1972; 34: 87–22. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Harrold J, Rickerson E, Carroll JT, McGrath J, Morales K, Kapo J, Casarett D. Is the palliative performance scale a useful predictor of mortality in a heterogeneous hospice population? J Palliat Med 2005; 8: 503–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lau F, Maida V, Downing M, Lesperance M, Karlson N, Kuziemsky C. Use of the palliative performance scale (PPS) for end‐of‐life prognostication in a palliative medicine consultation service. J Pain Symptom Manage 2009; 37: 965–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chan EY, Wu HY, Chan YH. Revisiting the palliative performance scale: change in scores during disease trajectory predicts survival. Palliat Med 2013; 27: 367–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Harris PS, Stalam T, Ache KA, Harrold JE, Craig T, Teno J, Smither E, Dougherty M, Casarett D. Can hospices predict which patients will die within six months? J Palliat Med 2014; 17: 894–898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lau F, Downing M, Lesperance M, Karlson N, Kuziemsky C, Yang J. Using the palliative performance scale to provide meaningful survival estimates. J Pain Symptom Manage 2009; 38: 134–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McGreevy CM, Bryczkowski S, Pentakota SR, Berlin A, Lamba S, Mosenthal AC. Unmet palliative care needs in elderly trauma patients: can the palliative performance scale help close the gap? Am J Surg 2017; 213: 778–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Johnson MJ. Heart failure and palliative care: time for action. Palliat Med 2018: 269216318804456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chow J, Senderovich H. It's time to talk: challenges in providing integrated palliative care in advanced congestive heart failure. a narrative review. Curr Cardiol Rev 2018; 14: 128–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Maciver J, Ross HJ. A palliative approach for heart failure end‐of‐life care. Curr Opin Cardiol 2018; 33: 202–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]