Abstract

The 3-min constant speed shuttle test (CSST) was used to examine the effect of tiotropium/olodaterol compared with tiotropium at reducing activity-related breathlessness in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

This was a randomised, double-blind, two-period crossover study including COPD patients with moderate to severe pulmonary impairment, lung hyperinflation at rest and a Mahler Baseline Dyspnoea Index <8. Patients received 6 weeks of tiotropium/olodaterol 5/5 µg and tiotropium 5 µg in a randomised order with a 3-week washout period. The speed for the 3-min CSST was determined for each patient such that an intensity of breathing discomfort ≥4 (“somewhat severe”) on the modified Borg scale was reached at the end of a completed 3-min CSST.

After 6 weeks, there was a decrease in the intensity of breathlessness (Borg dyspnoea score) at the end of the 3-min CSST from baseline with both tiotropium (mean –0.968, 95% CI −1.238– −0.698; n=100) and tiotropium/olodaterol (mean −1.325, 95% CI −1.594– −1.056; n=101). The decrease in breathlessness was statistically significantly greater with tiotropium/olodaterol versus tiotropium (treatment difference −0.357, 95% CI −0.661– −0.053; p=0.0217).

Tiotropium/olodaterol reduced activity-related breathlessness more than tiotropium in dyspnoeic patients with moderate to severe COPD exhibiting lung hyperinflation.

Short abstract

Tiotropium/olodaterol reduces activity-related breathlessness versus tiotropium in COPD http://ow.ly/MVyk30niV1o

Introduction

Breathlessness during physical exertion is a prominent and distressing symptom of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) that causes patients to avoid daily activities, leading to physical deconditioning and reduced quality of life [1–3]. While several clinical trials have confirmed that long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs) improve activity-related breathlessness [4–6], it is unclear to what extent the addition of a second long-acting bronchodilator further reduces activity-related breathlessness compared with a LAMA alone [7]. This is a relevant question considering that LAMA/long-acting β2-agonist (LABA) therapy is viewed as the preferred initial treatment option in patients with Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) grades B and D COPD, and reducing breathlessness is a major goal of COPD therapy [8].

Activity-related breathlessness can be measured during patients’ daily lives using questionnaires such as the Mahler Baseline Dyspnoea Index (BDI)/Transition Dyspnoea Index (TDI) or Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire. Alternatively, activity-related breathlessness may be measured in a laboratory environment using standardised exercise tests, which have the advantage of allowing precise control of the activity that produces breathlessness, an important prerequisite for assessing changes in breathlessness with therapy. We recently developed and validated the 3-min constant speed shuttle test (CSST), which was specifically designed to assess whether interventions alleviate activity-related breathlessness in patients with COPD [9, 10]. During this test, participants walk at a predetermined and externally imposed cadence for 3 min, with dyspnoea score measured at the end of the test. Importantly, the walking cadence is individualised so that a level of dyspnoea sufficiently intense to be amenable to therapy is generated in each participant. The short and fixed duration of the test means that the end-exercise (3 min) data-point is available for most patients in a clinical trial. The 3-min CSST only requires a small amount of space and minimal equipment, making it relatively easy to perform. Based on these considerations, we propose that this test is particularly well suited to investigate whether LAMA/LABA bronchodilation provides further breathlessness relief compared with LAMA monotherapy.

The aim of this study was to examine the effect of tiotropium/olodaterol compared with tiotropium at reducing breathlessness during the 3-min CSST in patients with COPD exhibiting lung hyperinflation at rest and significant breathlessness during everyday activities. Considering that dual bronchodilation provides further improvements in expiratory flow and resting hyperinflation compared with monotherapy [7, 11], we proposed that tiotropium/olodaterol would provide further breathlessness relief compared with tiotropium during the 3-min CSST.

Methods

Patients

Patients aged 40–75 years with moderate to severe COPD (post-bronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) ≥30% and <80% predicted), lung hyperinflation at rest (functional residual capacity (FRC) >120% predicted) and a significant degree of breathlessness during everyday activities (Mahler BDI <8) were included. Patients were current or ex-smokers with a smoking history >10 pack-years. Patients were excluded if they had a significant disease other than COPD, a current diagnosis of asthma, an exacerbation in the 6 weeks prior to screening or myocardial infarction within 6 months of screening. Patients with a contraindication for exercise (as per recommendations of the European Respiratory Society (ERS) Task Force on Standardisation of Clinical Exercise Testing [12]) were also excluded.

Study design

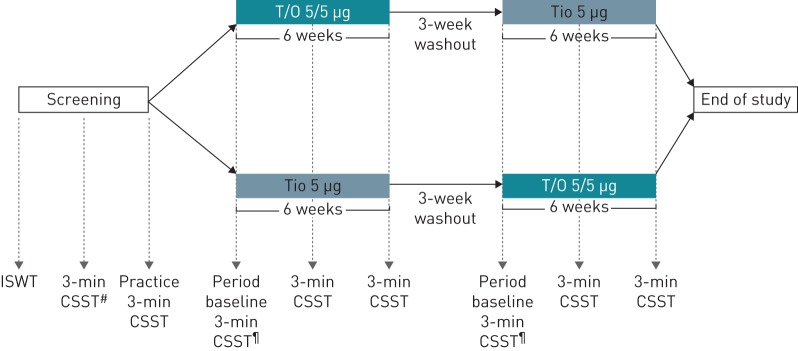

This was a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, two-period crossover study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02853123: OTIVATO) in which patients received tiotropium/olodaterol 5/5 µg once daily and tiotropium 5 µg once daily for 6 weeks each, in a randomised order with a 3-week washout period in between (figure 1). Both drugs were delivered once daily via the Respimat inhaler (Boehringer Ingelheim International, Ingelheim am Rhein, Germany). Patients on LABAs and/or LAMAs were required to undergo washout from these medications for at least 3 weeks prior to randomisation. Patients prescribed inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs) prior to the study continued therapy at a stable dose throughout the study. Patients receiving combined ICS/LABA were switched to an equivalent ICS monotherapy. Patients were evaluated for adverse events during the study period.

FIGURE 1.

Trial design. T/O: tiotropium/olodaterol; Tio: tiotropium; ISWT: incremental shuttle walk test; CSST: constant speed shuttle test. #: speed determination; ¶: at visits 4 and 7, a period baseline 3-min CSST was completed prior to dosing; at visits 5, 6, 8 and 9 a 3-min CSST was conducted 2 h (±15 min) after inhalation of the study medication.

Patients were randomised to a treatment sequence using an interactive voice/web response system. Randomisation was capped such that the proportion of GOLD stage 2 and 3 patients was ∼50% each.

Outcomes

The primary end-point was change from baseline to week 6 in intensity of breathlessness, measured using the modified Borg scale at the end of the 3-min CSST.

Secondary end-points were change from baseline to week 6 in resting inspiratory capacity, end of exercise inspiratory capacity, 1-h post-dose FEV1 and forced vital capacity (FVC), and intensity of breathlessness (modified Borg scale) at 1, 2 and 2.5 min during the 3-min CSST.

Incremental shuttle walk test

At the first screening visit, an incremental shuttle walk test (ISWT) was performed for all patients [13]. The ISWT was not required as part of the 3-min CSST protocol, but was included in the study to provide a measure of patients’ peak walking capacity at baseline. In this test, patients walk back and forth on a 10-m course, at a speed dictated by an audio signal.

3-min constant speed shuttle test

The 3-min CSST is performed on a flat, straight walking track. Patients walk back and forth on a 10-m course, keeping pace with the pre-recorded audio signal and completing a turn at each audio signal. They are allowed to run if necessary.

At the second screening visit, patients completed a minimum of two and up to three 3-min CSSTs at different sets of speeds (2.5, 3.25, 4, 5 or 6 km·h−1), always starting at 4 km·h−1. This was to determine the highest speed at which patients could complete the entire 3 min of the test and reach a Borg breathing discomfort rating of ≥4 out of 10. If the patient did not complete the full 3 min at 4 km·h−1, a lower walking speed was chosen for the next 3-min CSST (after a minimum 30-min rest period). If the patient completed the full 3 min at 4 km·h−1, a higher walking speed was chosen for the next 3-min CSST and the increase in speed was continued (up to 6 km·h−1), even if a Borg rating of ≥4 was reached at the end of the 3 min, until the patient was unable to complete the full 3 min of the test (supplementary figure S1). At a third screening visit, a practice 3-min CSST was performed at the speed selected at the previous visit; this speed was used for all subsequent tests.

Before, during (at 1, 2 and 2.5 min) and at the end of exercise, patients chose the phrase that best described their intensity of breathing discomfort and leg discomfort, from “0 or nothing at all (no discomfort)” to “10 or maximal (most severe discomfort you've ever experienced or could imagine experiencing)”. Patients reported their intensity of breathlessness verbally to the investigator walking alongside them during the 3-min CSST, with particular attention taken not to hinder the patient and to avoid any negative impact on the walking test. More detail can be found in the supplementary methods.

The 3-min CSST was performed after spirometry and 2 h after dosing at on-treatment clinic visits.

As this was the first time the 3-min CSST was used in a multicentre trial, only sites experienced in exercise testing were involved in the study. Detailed instructions were provided, and a proficiency test was implemented and monitored by a trainer to standardise the test across all sites.

Transition Dyspnoea Index

The BDI was administered at screening and baseline, and the TDI was administered at the end of each treatment period prior to dosing and study procedures.

Lung function testing

Forced spirometry was conducted at baseline and 1 h after the administration of study medication according to American Thoracic Society (ATS)/ERS criteria [14]. The highest FEV1 and FVC results obtained on any of three manoeuvres meeting the ATS/ERS criteria were selected.

In a slow spirometry manoeuvre, inspiratory capacity was measured at rest using mobile cardiopulmonary exercise equipment (Spiropalm; Cosmed, Rome, Italy). At least three reproducible measurements were obtained (a maximum of five measurements performed). The mean of the two highest acceptable efforts was used for analysis.

Physiological measures

Ventilation, tidal volume and breathing frequency were continuously recorded during the 3-min CSSTs using the same mobile cardiopulmonary exercise equipment as for the inspiratory capacity measurements. Heart rate and arterial oxygen saturation measured by pulse oximetry were also recorded during the tests. FRC was measured at the screening visit using constant volume, variable pressure body plethysmography in accordance with the ATS/ERS guidelines [15].

Analysis

A sample size of 102 was required to detect a difference between tiotropium/olodaterol and tiotropium of 0.5 Borg units with 80% power and a type I error rate of 0.05 (two-sided), assuming a standard deviation of 1.776, based on a previous pilot study [10].

The primary and secondary end-points were analysed using a restricted maximum likelihood-based mixed effect repeated measures model, with treatment and period as fixed effects, patient as a random effect, and period baseline and patient baseline as covariates. Period baseline is the pre-dose measurement from the first day of each period, whereas patient baseline is the mean of nonmissing period baselines for each patient. Patient baseline data are used to calculate change from baseline.

The efficacy analysis was performed in all randomised patients who were documented to have taken any dose of trial medication, and who had both baseline and any evaluable post-baseline measurement for the primary end-point. Missing data at a given visit were imputed by the available data from the patient at that visit; missing visits were handled through the statistical model.

All calculated p-values should be considered descriptive for the analysis of the secondary and further end-points as no adjustment for multiple testing was done for these comparisons.

A responder analysis was conducted using a ≥1-point improvement in the modified Borg dyspnoea score as the threshold for response [16].

Results

Patients

The study was conducted in 12 centres in Belgium, Canada, Germany and the Netherlands.

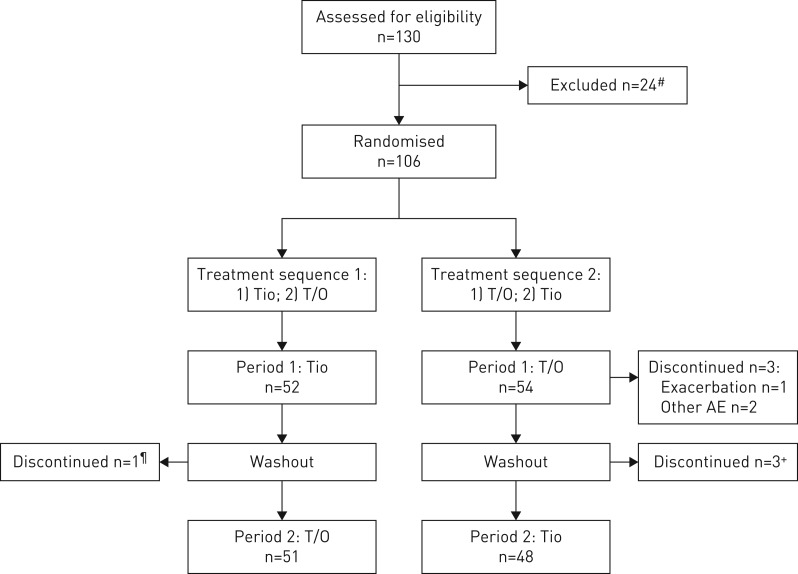

Overall, 106 patients were randomised. 52 patients were randomised to receive tiotropium and then tiotropium/olodaterol, with one discontinuing during washout before starting tiotropium/olodaterol. 54 patients were randomised to receive tiotropium/olodaterol first and then tiotropium; three discontinued during the tiotropium/olodaterol period and three during the washout period (figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Patient disposition (crossover trial). T/O: tiotropium/olodaterol; Tio: tiotropium; AE: adverse event. #: reasons for exclusion (screen failures) are shown in supplementary table S1; ¶: due to other AE; +: all due to exacerbations.

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics are shown in table 1. Mean post-bronchodilator FEV1 at baseline was 1.561 L (54.4% predicted) and most patients (95.3%) were receiving COPD therapy prior to study enrolment.

TABLE 1.

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics (treated set)

| Subjects | 106 |

| Male | 66 (62.3) |

| Age years | 63.6±7.2 |

| Smoking history pack-years | 45.6±20.7 |

| Baseline Dyspnoea Index | 5.8±1.3 |

| Post-bronchodilator lung function at screening | |

| FEV1 L | 1.561±0.525 |

| FEV1 % pred | 54.4±13.0 |

| GOLD stage 2 | 60 (56.6) |

| GOLD stage 3 | 46 (43.4) |

| FEV1 change from pre-bronchodilator L | 0.232±0.188 |

| FEV1 change from pre-bronchodilator % | 19.5±15.5 |

| FVC L | 3.433±1.025 |

| FEV1/FVC % | 45.8±8.9 |

| FRC % pred | 155.4±28.2 |

| Total lung capacity L | 7.3±1.5 |

| Pulmonary medication prior to study enrolment | |

| Any | 101 (95.3) |

| LABA monotherapy | 0 (0) |

| LAMA monotherapy | 18 (17.0) |

| LABA/ICS# | 7 (6.6) |

| LAMA/ICS# | 1 (0.9) |

| LAMA/LABA# | 18 (17.0) |

| LAMA/LABA/ICS# | 41 (38.7) |

Data are presented as n, n (%) or mean±sd. FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 s; GOLD: Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; FVC: forced vital capacity; FRC: functional residual capacity; LABA: long-acting β2-agonist; LAMA: long-acting muscarinic antagonist; ICS: inhaled corticosteroid. #: free or fixed-dose combination (LABA or LAMA discontinued prior to randomisation for duration of study; ICS continued if used prior to study enrolment).

At baseline, mean±sd distance walked during the ISWT was 434.6±128.0 m; this was achieved during a mean±sd time of 429.4±82.9 s. Mean±sd Borg scale breathing discomfort at the end of the ISWT was 5.160±1.318.

The selected speed for the 3-min CSST was 4 km·h−1 in 27.4% of patients, 5 km·h−1 in 48.1% of patients and 6 km·h−1 in 17.9% of patients. It was 2.5 and 3.25 km·h−1 in 1.9% and 4.7% of patients, respectively.

The patient baseline mean±se intensity of breathing discomfort at the end of the 3-min CSST was 5.158±0.159 Borg units (a Borg score of 5 is “severe”), while the intensity of leg discomfort was 3.158±0.223 Borg units (a Borg score of 3 is “moderate”). Breathing discomfort scores and inspiratory capacity were similar at the start of the first treatment period and the start of the second treatment period (supplementary results).

Primary end-point

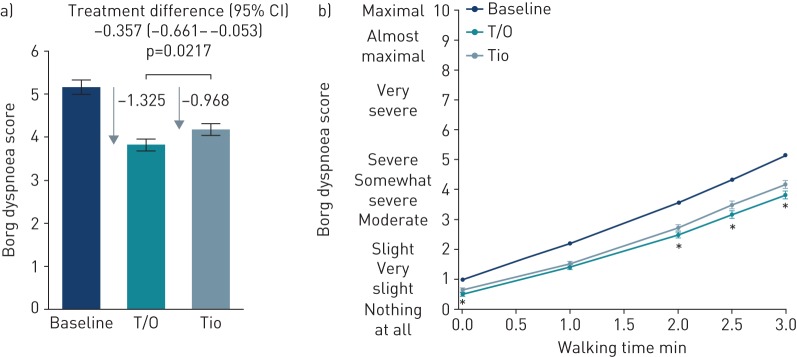

After 6 weeks of treatment, there was a decrease in the intensity of breathlessness (Borg dyspnoea score) at the end of the 3-min CSST with both tiotropium (mean −0.968, 95% CI −1.238– −0.698) and tiotropium/olodaterol (mean −1.325, 95% CI −1.594– −1.056) compared with baseline. This greater reduction in the intensity of breathlessness with tiotropium/olodaterol versus tiotropium was statistically significant (treatment difference −0.357, 95% CI −0.661– −0.053; p=0.0217) (figure 3a).

FIGURE 3.

Borg dyspnoea score: a) at the end of the 3-min constant speed shuttle test (CSST) (primary end-point) and b) during the 3-min CSST, after 6 weeks of treatment. T/O: tiotropium/olodaterol (n=101); Tio: tiotropium (n=100). Data are presented as mean±se. *: p<0.05 T/O versus Tio.

Secondary end-points

Intensity of breathlessness during the 3-min CSST

The intensity of breathlessness after 6 weeks with tiotropium/olodaterol and tiotropium at all time-points during the 3-min CSST is shown in figure 3b; both drugs showed an improvement from baseline, with significant improvements observed with tiotropium/olodaterol versus tiotropium from the 2-min time-point until the end of the test.

Lung function

Mean±se pre-treatment baseline resting inspiratory capacity was 2.312±0.072 L; after 6 weeks of treatment there was an increase in resting inspiratory capacity of 0.271±0.049 L for tiotropium and a larger increase of 0.489±0.049 L for tiotropium/olodaterol (treatment difference of 0.218 L, 95% CI 0.121–0.314 L; p<0.0001) (table 2). Results after 3 weeks are shown in supplementary table S2.

TABLE 2.

Lung function parameters after 6 weeks of treatment (full analysis set)

| Value | Change from baseline | Mean (95% CI) difference versus tiotropium | p-value# | |

| Resting inspiratory capacity L | ||||

| Baseline | 2.312±0.072 | |||

| Tiotropium (n=100) | 2.590±0.049 | 0.271±0.049 | ||

| Tiotropium/olodaterol (n=101) | 2.808±0.049 | 0.489±0.049 | 0.218 (0.121–0.314) | <0.0001 |

| FEV1 L | ||||

| Baseline | 1.325±0.049 | |||

| Tiotropium (n=99) | 1.485±0.021 | 0.163±0.021 | ||

| Tiotropium/olodaterol (n=103) | 1.641±0.021 | 0.318±0.021 | 0.155 (0.117–0.194) | <0.0001 |

| FVC L | ||||

| Baseline | 3.054±0.100 | |||

| Tiotropium (n=99) | 3.307±0.040 | 0.258±0.040 | ||

| Tiotropium/olodaterol (n=103) | 3.507±0.039 | 0.459±0.039 | 0.201 (0.134–0.267) | <0.0001 |

Data are presented as mean±se, unless otherwise stated. FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC: forced vital capacity. #: between-group differences.

FEV1 and FVC, measured 1 h post-dose, were also significantly improved with tiotropium/olodaterol versus tiotropium (treatment differences of 0.155 and 0.201 L, respectively; both p<0.0001) (table 2).

Intensity of breathlessness responder analysis

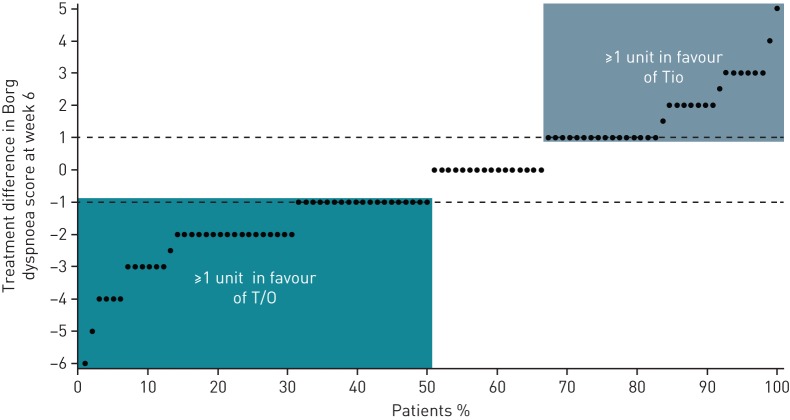

For this analysis, being a responder was defined as showing a ≥1-point improvement in the modified Borg dyspnoea score, a threshold based on the assumption that this would represent a clinically meaningful difference [17]. Figure 4 shows the proportion of patients with specific treatment differences in Borg dyspnoea score. 50% of patients achieved at least a 1-point improvement in Borg dyspnoea score with tiotropium/olodaterol compared with tiotropium, while 34% of patients achieved at least a 1-point improvement in Borg dyspnoea score with tiotropium compared with tiotropium/olodaterol. This resulted in a number needed to treat of n=7 to achieve a clinically relevant improvement in activity-related breathlessness for tiotropium/olodaterol compared with tiotropium.

FIGURE 4.

Treatment difference in Borg dyspnoea score at 6 weeks: tiotropium/olodaterol (T/O)–tiotropium (Tio). Each individual patient is represented by a single point. Negative scores indicate a larger reduction in Borg dyspnoea score with T/O and positive scores indicate a larger reduction in Borg dyspnoea score with Tio. The dotted lines represent changes in Borg dyspnoea score of 1 unit in both directions. Period baseline was used for this analysis.

TDI focal score

The TDI score was improved from baseline with tiotropium by 0.581 units (95% CI 0.031–1.132 units) and with tiotropium/olodaterol by 1.225 units (95% CI 0.680–1.770 units). The difference between treatments was 0.643 units (p=0.0659).

Physiological parameters

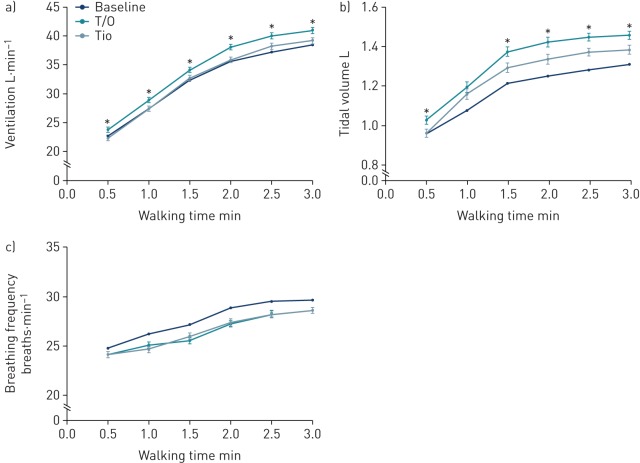

Ventilation and tidal volume were significantly increased with tiotropium/olodaterol compared with tiotropium at all time-points during the 3-min CSST after 6 weeks of treatment (p<0.05 except for the 1-min time-point for tidal volume) (figure 5). At the end of the 3-min CSST, there was an increase in ventilation of 1.732 L·min−1 (95% CI 0.591–0.559 L·min−1) with tiotropium/olodaterol compared with tiotropium and an increase in tidal volume of 0.073 L (95% CI 0.023–0.124 L). There were no differences between treatments in breathing frequency during the 3-min CSST (figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Physiological parameters measured during the 3-min constant speed shuttle test at 6 weeks: a) ventilation, b) tidal volume and c) breathing frequency. T/O: tiotropium/olodaterol (n=101); Tio: tiotropium (n=100). Data are presented as mean±se. *: p<0.05 T/O versus Tio.

Adverse events

60 patients (57.1%) in the tiotropium/olodaterol group and 50 patients (50.0%) in the tiotropium group reported adverse events. The number of patients reporting serious adverse events was small in both groups (five during the tiotropium/olodaterol period and one during the tiotropium period) (supplementary table S3).

Discussion

The present study is the first to examine the effects of LAMA/LABA treatment (in this case tiotropium/olodaterol) versus a LAMA (tiotropium) on breathlessness during the 3-min CSST and the first to implement the 3-min CSST in a multicentre, international trial. Our results support the hypothesis that the benefits of tiotropium/olodaterol over tiotropium in terms of improving lung function and reducing hyperinflation lead to a reduction in activity-related breathlessness (see video abstract in the supplementary material).

While both bronchodilator treatments were effective at improving breathlessness during the 3-min CSST, the study showed further benefits of tiotropium/olodaterol versus tiotropium in patients with lung hyperinflation at rest. The mean treatment difference in Borg dyspnoea score was modest (0.357 Borg score unit difference) and below the 1-unit threshold that is likely to be perceived by patients (i.e. clinically significant) [16, 17], which may be because the comparator in this study was not placebo but tiotropium, a potent treatment to alleviate breathlessness [4]. However, the results also showed that more patients reached the 1-point threshold of breathlessness reduction with tiotropium/olodaterol than with tiotropium, resulting in a number needed to treat of n=7 for one additional patient to benefit from tiotropium/olodaterol compared with tiotropium. The number needed to treat is slightly better than that reported for another LAMA/LABA combination versus tiotropium for a 1-point improvement in TDI score (number needed to treat of n=11) [18]. Given the favourable safety profile of dual bronchodilators, we suggest that a number needed to treat of n=7 for a clinical outcome such as dyspnoea is clinically relevant [19]. In figure 4, we present the individual data for changes in intensity of breathlessness with both treatments. There are a minority of patients who appear to do better with bronchodilator monotherapy than with dual bronchodilation. This observation is consistent with previous studies [20, 21]. For example, the BLAZE investigators [21] reported in patients with moderate COPD that the mean difference in TDI score between dual bronchodilation and bronchodilator monotherapy was 0.36 (95% CI −0.15–0.87), implying that some patients did better on tiotropium alone. Likewise, a recent network meta-analysis of the effects of dual bronchodilation on exercise tolerance in COPD reported data from several individual studies where the improvement in exercise tolerance could be greater with bronchodilator monotherapy than with dual bronchodilator therapy [20]. These observations do not mean that patients are worse with dual bronchodilation, but rather that the translation from improved lung function to clinical outcomes (e.g. exercise duration or dyspnoea) is not always straightforward. Issues with variation in magnitude of bronchodilation and deflation responses, the interpretation of the questionnaires by patients as well as other factors could modulate the impact of bronchodilation on perceived dyspnoea and other outcomes.

Overall, our study extends the previous finding that dual bronchodilation improves patient-reported breathlessness in COPD compared with bronchodilator monotherapy [21–23] by providing the first demonstration of added benefits of tiotropium/olodaterol over bronchodilator monotherapy to alleviate activity-related breathlessness. Unique to this trial was the use of the 3-min CSST in which the exercise stimulus was standardised across measurements.

The results are also consistent with previous studies in which breathlessness was measured using the TDI [21, 23]. In these studies, LAMA/LABA offered greater benefits than LAMA alone, but the benefits of dual bronchodilation over monotherapy were not as great as the difference between LAMA and placebo. In previous tiotropium/olodaterol trials there was an additive effect of tiotropium and olodaterol on the TDI and St George's Respiratory Questionnaire responder rates [24], but the mean change was less than the minimal clinically important difference [23]. The TDI data in the present trial are also similar to those previously published, and although the treatment difference did not reach statistical significance, a clinically important mean improvement of >1 unit [16] from baseline was observed with tiotropium/olodaterol only.

Our data support the role of bronchodilators in improving breathlessness during activity in patients with COPD by improving lung function and reducing hyperinflation [1, 7]. This allows patients to exercise for longer before being limited by symptoms [2, 4]. In previous studies [11], and particularly in another tiotropium/olodaterol exercise trial (MORACTO) [7], it has been difficult to differentiate between LAMA/LABA combinations and monotherapies in terms of activity-related breathlessness. The different findings between the present study and MORACTO can be explained by the study designs. Different exercise tests were used (walking versus cycling; time-limited versus symptom-limited) and the 3-min CSST used in our trial is specifically designed to measure changes in breathlessness. The patient population also differed: in the present study, a breathlessness signal was required (≥4 units on the Borg scale) during the 3-min CSST at study entry.

Patients recruited also had hyperinflation at baseline (FRC >120% predicted) and perhaps because of this there was a much greater treatment difference in inspiratory capacity than was found in MORACTO (0.218 versus 0.101 L) or in a meta-analysis of eight clinical trials comparing LAMA/LABA with LAMA [20]. The 120% predicted FRC threshold was chosen to be consistent with the definition previously used in several COPD exercise studies [4, 5, 25]. Perhaps the greatest effects on activity-related breathlessness may be found in patients with hyperinflation at baseline. Similarly, the selected FRC threshold identifies a subgroup of patients that is more likely to improve exercise endurance following bronchodilation [26].

The large increases in inspiratory capacity, an indirect measure of hyperinflation, represent ∼0.5 L reduction in FRC (assuming only small changes in total lung capacity following bronchodilator treatment [27]). As expected, and consistent with previous studies [28], there were also improvements in FEV1 and FVC, and increases in ventilation driven by increases in tidal volume during the 3-min CSST with tiotropium/olodaterol versus tiotropium. Notably, the intensity of breathlessness was diminished despite the increase in ventilation with tiotropium/olodaterol versus tiotropium. This suggests that additional lung deflation with dual bronchodilation ultimately resulted in a more favourable positioning of tidal volume on the sigmoidal pressure–volume relation of the relaxed respiratory system. Thus, the attendant reduced mechanical (elastic) loading and functional weakness of the inspiratory muscle and expanded inspiratory reserve volume would be expected to reduce inspiratory neural drive to the inspiratory muscles, an important source of respiratory discomfort in COPD [25].

The changes in breathing pattern were likely related to improvements in airflows, an important determinant of ventilatory capacity and inspiratory capacity [10, 29, 30]. From a physiological perspective, these increases in ventilation and tidal volume were likely beneficial to increase alveolar ventilation. However, the reduction in breathlessness with dual bronchodilation could have been even larger than currently reported had the Borg dyspnoea score been corrected for the increased ventilation.

This study shows that the 3-min CSST can be successfully implemented in a multicentre clinical trial, and is a sensitive enough tool to detect a difference in breathlessness between LAMA/LABA and LAMA. Great care was taken in selecting a shuttle speed that allowed all patients to complete the full 3 min at each study visit while still eliciting at least a “somewhat severe” breathlessness (score ≥4 on the Borg dyspnoea scale) that would be amenable to therapy. The baseline results show that a meaningful degree of dyspnoea was achieved with the 3-min CSST, with little heterogeneity between patients. There were, however, a few limitations of our study. Despite the care taken, some patients who met the inclusion criteria in the screening 3-min CSST were either unable to complete the 3-min test during baseline tests or rated breathing discomfort less than “somewhat severe” at the end of the test in visits following the determination of the final speed used during the trial. These patients continued in the trial per the protocol. This is likely unavoidable given the day-to-day variability in COPD patients’ clinical status. The selection of shuttle speed is labour intensive; future work to determine an appropriate shuttle speed based on patient characteristics may be of value. Additionally, the results at 3 weeks were not consistent with the results at 6 weeks (supplementary figure S2). This was a surprising finding and it is not clear what caused this difference.

As well as these clinical results, our study provides potentially useful information about the 3-min CSST, a novel tool to assess exertional dyspnoea, an area where there is a need for methodological development [31]. The demonstration of the feasibility of using the 3-min CSST in the context of a multicentre clinical trial and of its responsiveness to interventions may be worthwhile for the design of future clinical trials evaluating the impact of various therapies on dyspnoea, a key outcome parameter in COPD.

The safety data show a slightly higher proportion of patients with adverse events in the tiotropium/olodaterol period compared with the tiotropium period, but this was a small population and a relatively short trial. A large safety database of longer-term and larger trials has shown that there is no difference between tiotropium/olodaterol and tiotropium in the proportion of patients with adverse events [32, 33].

Overall, we report that tiotropium in combination with olodaterol was more effective than tiotropium monotherapy at alleviating activity-related breathlessness in patients with COPD and hyperinflation. The study provides supporting evidence for the use of dual bronchodilation in COPD because it offers the best chance of optimising dyspnoea status in this disease.

Supplementary material

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material ERJ-02049-2018_Supplement

OTIVATO TRIAL INFOGRAPHIC OTIVATO_primary_static_infographic_01_Feb

Video abstract ERJ-02049-2018_video_abstract (63.9MB, mp4)

Acknowledgements

Medical writing assistance, in the form of the preparation and revision of the manuscript, was supported financially by Boehringer Ingelheim and provided by Claire Scofield (MediTech Media, Manchester, UK), under the authors’ conceptual direction and based on feedback from the authors.

Footnotes

This article has supplementary material available from erj.ersjournals.com

This study is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov with identifier NCT02853123. To ensure independent interpretation of clinical study results, Boehringer Ingelheim grants all external authors access to all relevant material, including participant-level clinical study data, and relevant material as needed by them to fulfil their role and obligations as authors under the ICMJE criteria. Furthermore, clinical study documents (e.g. study report, study protocol, statistical analysis plan) and participant clinical study data are available to be shared after publication of the primary manuscript and if regulatory activities are complete and other criteria met per the Boehringer Ingelheim Policy on Transparency and Publication of Clinical Study Data: https://trials.boehringer-ingelheim.com/transparency_policy.html. Prior to providing access, documents will be examined, and, if necessary, redacted and the data will be de-identified, to protect the personal data of study participants and personnel, and to respect the boundaries of the informed consent of the study participants. Clinical study reports and related clinical documents can be requested via this link: https://trials.boehringer-ingelheim.com/trial_results/clinical_submission_documents.html. All such requests will be governed by a document sharing agreement. Bona fide, qualified scientific and medical researchers may request access to de-identified, analysable participant clinical study data with corresponding documentation describing the structure and content of the datasets. Upon approval, and governed by a data sharing agreement, data are shared in a secured data access system for a limited period of 1 year, which may be extended upon request. Researchers should use https://clinicalstudydatarequest.com to request access to study data.

Conflict of interest: F. Maltais reports research support from Boehringer Ingelheim, GSK, AstraZeneca, Grifols and Novartis, advisory board participation for Boehringer Ingelheim and GSK, and speaking engagements for Boehringer Ingelheim, Grifols and Novartis.

Conflict of interest: J-L. Aumann has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: A-M. Kirsten reports institutional compensation for clinical trials from Boehringer Ingelheim, during the conduct of the study; has lectured for Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca and Berlin-Chemie, and reports institutional compensation for clinical trials from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche, GSK, Novartis, Chiesi, Bayer Healthcare and Sanofi, outside the submitted work.

Conflict of interest: É. Nadreau has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: H. Macesic is an employee of Boehringer Ingelheim.

Conflict of interest: X. Jin is an employee of Boehringer Ingelheim.

Conflict of interest: A. Hamilton is an employee of Boehringer Ingelheim.

Conflict of interest: D.E. O'Donnell reports grants from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim and GSK, during the conduct of the study; and personal fees for serving on speaker bureaus, consultation panels and advisory boards from Almirall, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GSK, Novartis and Pfizer, outside the submitted work.

Support statement: This study was funded by Boehringer Ingelheim. Funding information for this article has been deposited with the Crossref Funder Registry.

References

- 1.Thomas M, Decramer M, O'Donnell DE. No room to breathe: the importance of lung hyperinflation in COPD. Prim Care Respir J 2013; 22: 101–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O'Donnell DE. Hyperinflation, dyspnea, and exercise intolerance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2006; 3: 180–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Victorson DE, Anton S, Hamilton A, et al. A conceptual model of the experience of dyspnea and functional limitations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Value Health 2009; 12: 1018–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Donnell DE, Fluge T, Gerken F, et al. Effects of tiotropium on lung hyperinflation, dyspnoea and exercise tolerance in COPD. Eur Respir J 2004; 23: 832–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maltais F, Hamilton A, Marciniuk D, et al. Improvements in symptom-limited exercise performance over 8 h with once-daily tiotropium in patients with COPD. Chest 2005; 128: 1168–1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beeh KM, Singh D, Di Scala L, et al. Once-daily NVA237 improves exercise tolerance from the first dose in patients with COPD: the GLOW3 trial. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2012; 7: 503–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O'Donnell DE, Casaburi R, Frith P, et al. Effects of combined tiotropium/olodaterol on inspiratory capacity and exercise endurance in COPD. Eur Respir J 2017; 49: 1601348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease 2017. http://goldcopd.org/gold-2017-global-strategy-diagnosis-management-prevention-copd Date last accessed: October 26, 2017.

- 9.Perrault H, Baril J, Henophy S, et al. Paced-walk and step tests to assess exertional dyspnea in COPD. COPD 2009; 6: 330–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sava F, Perrault H, Brouillard C, et al. Detecting improvements in dyspnea in COPD using a three-minute constant rate shuttle walking protocol. COPD 2012; 9: 395–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beeh KM, Korn S, Beier J, et al. Effect of QVA149 on lung volumes and exercise tolerance in COPD patients: the BRIGHT study. Respir Med 2014; 108: 584–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.ERS Task Force on Standardization of Clinical Exercise Testing. Clinical exercise testing with reference to lung diseases: indications, standardization and interpretation strategies. Eur Respir J 1997; 10: 2662–2689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh SJ, Morgan MD, Scott S, et al. Development of a shuttle walking test of disability in patients with chronic airways obstruction. Thorax 1992; 47: 1019–1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J 2005; 26: 319–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wanger J, Clausen JL, Coates A, et al. Standardisation of the measurement of lung volumes. Eur Respir J 2005; 26: 511–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones PW, Beeh KM, Chapman KR, et al. Minimal clinically important differences in pharmacological trials. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014; 189: 250–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ries AL. Minimally clinically important difference for the UCSD Shortness of Breath Questionnaire, Borg Scale, and Visual Analog Scale. COPD 2005; 2: 105–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rodrigo GJ, Plaza V. Efficacy and safety of a fixed-dose combination of indacaterol and glycopyrronium for the treatment of COPD: a systematic review. Chest 2014; 146: 309–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Citrome L, Ketter TA. When does a difference make a difference? Interpretation of number needed to treat, number needed to harm, and likelihood to be helped or harmed. Int J Clin Pract 2013; 67: 407–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Calzetta L, Ora J, Cavalli F, et al. Impact of LABA/LAMA combination on exercise endurance and lung hyperinflation in COPD: a pair-wise and network meta-analysis. Respir Med 2017; 129: 189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mahler DA, Decramer M, D'Urzo A, et al. Dual bronchodilation with QVA149 reduces patient-reported dyspnoea in COPD: the BLAZE study. Eur Respir J 2014; 43: 1599–1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mahler DA, Keininger DL, Mezzi K, et al. Efficacy of indacaterol/glycopyrronium in patients with COPD who have increased dyspnea with daily activities. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis 2016; 3: 758–768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh D, Ferguson GT, Bolitschek J, et al. Tiotropium+olodaterol shows clinically meaningful improvements in quality of life. Respir Med 2015; 109: 1312–1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferguson GT, Karpel J, Bennett N, et al. Effect of tiotropium and olodaterol on symptoms and patient-reported outcomes in patients with COPD: results from four randomised, double-blind studies. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med 2017; 27: 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Donnell DE, Hamilton AL, Webb KA. Sensory–mechanical relationships during high-intensity, constant-work-rate exercise in COPD. J Appl Physiol 2006; 101: 1025–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Di Marco F, Sotgiu G, Santus P, et al. Long-acting bronchodilators improve exercise capacity in COPD patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir Res 2018; 19: 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'Donnell DE, Forkert L, Webb KA. Evaluation of bronchodilator responses in patients with “irreversible” emphysema. Eur Respir J 2001; 18: 914–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buhl R, Maltais F, Abrahams R, et al. Tiotropium and olodaterol fixed-dose combination versus mono-components in COPD (GOLD 2–4). Eur Respir J 2015; 45: 969–979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Donnell DE, Lam M, Webb KA. Spirometric correlates of improvement in exercise performance after anticholinergic therapy in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999; 160: 542–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O'Donnell DE, Lam M, Webb KA. Measurement of symptoms, lung hyperinflation, and endurance during exercise in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998; 158: 1557–1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mahler DA, Sethi S. To improve COPD care: a new instrument is needed to assess dyspnea. Chest 2018; 154: 235–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buhl R, Magder S, Bothner U, et al. Long-term general and cardiovascular safety of tiotropium/olodaterol in patients with moderate to very severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med 2017; 122: 58–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferguson GT, Buhl R, Voss F, et al. Safety of tiotropium/olodaterol in COPD: pooled analysis of three large, 52–week randomized clinical trials. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018; 197: A3035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material ERJ-02049-2018_Supplement

OTIVATO TRIAL INFOGRAPHIC OTIVATO_primary_static_infographic_01_Feb

Video abstract ERJ-02049-2018_video_abstract (63.9MB, mp4)