Abstract

Sessile serrated adenoma/polyps (SSA/Ps) of the colon account for 20–30% of all colon cancers. Small non-coding RNAs, including microRNAs (miRNAs), may function as oncogenes or tumor suppressor genes involved in cancer development. Small RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) was used to characterize miRNA profiles in SSA/Ps, hyperplastic polyps (HPs), adenomatous polyps and paired uninvolved colon. Our 108 small RNA-seq samples’ results were compared to small RNA-seq data from 212 colon cancers from the Cancer Genome Atlas. Twenty-three and six miRNAs were differentially expressed in SSA/Ps compared to paired uninvolved colon and HPs, respectively. Differential expression of MIR31-5p, MIR135B-5p and MIR378A-5p was confirmed by RT-qPCR. SSA/P-specific miRNAs are similarly expressed in colon cancers containing genomic aberrations described in serrated cancers. Correlation of miRNA expression with consensus molecular subtypes suggests more than one subtype is associated with the serrated neoplasia pathway. Canonical pathway analysis suggests many of these miRNAs target growth factor signaling pathways.

Keywords: colon cancer, gene expression, hyperplastic polyps, microRNAs, RNA sequencing, sessile serrated adenoma/polyps

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Serrated colon polyps are commonly found during screening colonoscopy and are subdivided into hyperplastic polyps (HPs), sessile serrated adenoma/polyps (SSA/Ps), and traditional serrated adenomas.1 Traditional serrated adenomas are rare while SSA/Ps and HPs are common. Unlike HPs, SSA/Ps may contribute up to a third of all colon cancers.2–4 However, differentiating SSA/Ps from HPs is often difficult in clinical practice, and better markers of SSA/Ps are needed for accurate diagnosis and subsequent cancer prevention strategies.5,6 We have previously defined an RNA signature in SSA/Ps that distinguishes SSA/Ps from HPs and identifies a subtype of colon cancer likely to develop from SSA/Ps.7,8

The serrated polyposis syndrome (SPS) is an extreme phenotype that often presents with multiple serrated polyps and carries a high risk (up to 42%) of colon cancer development.9–11 In clinical practice patients with SPS are routinely screened with annual colonoscopy, while patients with sporadic SSA/Ps are screened every 3 to 5 years. Unlike familial adenomatous polyposis and Lynch syndrome, SPS lacks a known underlying genetic mutation. SPS is likely influenced by epigenetic mechanisms that do not require mutations in protein-coding genes. Increased methylation of gene promoters at CpG islands is observed in SSA/Ps and the underlying colon mucosa of SPS patients, suggesting that such methylation may contribute to altered gene expression in SSA/Ps.2 However, it remains unknown what changes in RNA expression in SSA/Ps are required for progression to cancer.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small non-coding RNAs of 18–24 nucleotides that regulate gene expression through mRNA degradation and translation inhibition.12 A single miRNA may influence the expression of thousands of genes and multiple cellular processes necessary for the development of colon polyps and cancer.13 MiRNA expression may also be regulated by DNA methylation.14 Studies investigating miRNA-mRNA interactions in colon cancer cell lines have identified gene networks contributing to a malignant phenotype.15 We have investigated miRNA expression by small RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) in prospectively collected colon polyps and normal colon to identify gene networks important in the serrated pathway to colon cancer.

The few studies describing miRNA expression in serrated colon polyps have used microarray or reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) with retrospectively collected formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue samples,,16–18 rather than the much more comprehensive RNA-seq approach used in this study and presented for the first time. Also, no prior studies have examined mRNA targets of miRNAs differentially expressed in SSA/Ps. Our RNA sequencing analysis provides a more sensitive and complete analysis of miRNAs, including the discovery of unannotated, novel small RNAs. The goals of our study are threefold: First, define miRNA signatures for serrated polyp subtypes, SSA/Ps and HPs; second, compare serrated polyp-specific miRNAs with colon cancer subtype miRNA profiles; and third, identify signaling pathways likely playing a role in SSA/P development. We describe a unique miRNA profile in SSA/Ps that correlates with specific genomic aberrations and consensus molecular subtypes (CMSs) of colon cancer. We identify both growth factor and developmental signaling pathways in SSA/Ps that may drive progression to colon cancer.

2 |. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 |. Patients

Biopsy samples were obtained from routine screening or surveillance colonoscopy patients between the age of 46 and 80 who visited University of Utah Health Care Hospitals. Patients with SPS were between the age of 25 and 76. Subjects with family history of colon cancer, familial cancers including familial adenomatous polyposis and Lynch syndrome, history of inflammatory bowel disease or prior colonic resections were excluded. Samples for RNA sequencing were prospectively collected from 2011 to 2016. All patients provided informed consent as approved by the University of Utah’s Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Ten SSA/Ps with matched uninvolved mucosa and two HPs without matched uninvolved mucosa were obtained from six patients with SPS.7 SSA/Ps from five of these patients were previously analyzed by long mRNA sequencing.8 Right colon was defined as the colonic region from splenic flexure to cecum. Left colon was defined as descending colon to rectum. Sporadic SSA/Ps (n = 6, five right colon, one left colon), HPs (n = 12, two right colon, ten left colon), and adenomatous polyps (APs, n = 14, ten right colon, four left colon) along with matched uninvolved mucosa (n = 26) were collected from screening colonoscopy patients. Normal colon tissue (n = 30, 15 right colon, 15 left colon) was obtained from patients with no polyps or other pathology found on current or prior exams. If polyps were found during colonoscopy, biopsies of polyp tissue were collected for both routine histopathological diagnosis and for storage in RNAlater as previously described.7 All samples were collected prospectively and placed in RNAlater immediately after removal, stored at 4°C overnight and then at −80°C prior to performing RNA isolation.

2.2 |. FFPE tissue samples

Forty-seven FFPE samples, consisting of 26 SSA/Ps and 21 HPs, were obtained from the University of Utah’s pathology tissue core. Patients had granted consent under IRB-approved protocols for tissue banking. Samples were collected between years 2012 and 2018.

2.3 |. Pathological classification

All biopsy specimens were reviewed by expert gastroenterology pathologists at the University of Utah. Serrated polyps were classified according to the recent recommendations of the Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer (CRC) for post-polypectomy surveillance and as described previously.7,8,19 None of the SSA/Ps used in this study showed dysplasia.

2.4 |. RNA isolation

Total RNA was isolated from colon biospecimens using TRIzol (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and the Direct-zol RNA MiniPrep kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA) according to manufacturer protocol. Briefly, each colon sample (20–50 mg tissue) was homogenized in 1 mL of TRI-zol using a tissue homogenizer (Benchmark), and the homogenate was loaded onto Zymo-Spin IC columns. After on-column DNA digestion with DNase 1, the quantity of the eluted RNA was determined by NanoDrop 1000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) spectrophotometry. For FFPE samples, ten 10-μm paraffin sections of each FFPE tissue sample were deparaffinized with Neo-Clear (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH) and total RNA isolated using the Roche Diagnostics High Pure miRNA isolation kit.

2.5 |. Small RNA sequencing, alignments, and quality control

Small RNA sequencing was performed on 108 individual colon samples: 16 SSA/Ps (10 syndromic and 6 sporadic), 14 HPs, 14 APs, 34 uninvolved colon from the above polyp patients and 30 normal control colonic samples from patients without polyps or other colon pathology. Three small RNA-Seq runs of 11, 54, and 43 samples were performed during the course of the study. PCR-amplified cDNA sequencing libraries were prepared using NEBnext (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA) multiplex small RNA library prep (97 samples) or Illumina TruSeq small RNA sample prep (11 samples) according to the manufacturers’ protocols. Illumina single-end 50 bp sequence reads were performed with an Illumina HiSeq 2500 instrument. After removal of adapter sequences, sequence reads were aligned to the GRCh38/Hg38 human reference genome using novoalign (Novocraft) or STAR aligners.20 Visualization tracks were prepared for each dataset using the USeqRead Coverage application and viewed using the Integrated Genome Browser as previously described.8 Quality control metrics and novel miRNA predictions were performed using the online bioinformatics application Oasis.21 All raw and processed RNA-seq data files are available from the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE118504.

2.6 |. Differential expression analysis

2.6.1 |. Polyp comparisons to paired uninvolved colon

Differentially expressed small RNAs across polyp subtypes were identified using paired DESeq2 statistics implemented in the online bioinformatics application Oasis.21,22 To avoid potential batch effects, each polyp and corresponding paired uninvolved colon were run in the same small RNA-Seq run. Among HPs, 10 of 14 had paired uninvolved tissue available. Paired uninvolved tissue was available and used for all SSA/Ps and APs. The P values were controlled for multiple testing using the Benjamini and Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) method. Hierarchical clustering of differentially expressed genes was performed using Cluster 3.0 and Java Treeview software as previously described.7,8

2.6.2 |. Serrated polyp and control colon comparisons

Normalization of small RNA-seq data from SSA/Ps (n = 16), HPs (n = 14), matched right uninvolved colon (n = 10), control right (n = 15), and control left colon (n = 15) was performed using the voom method as part of the limma package in Bioconductor.23 Statistical differences in small RNA levels between SSA/Ps and HPs, uninvolved and control right colon, and control left and right colon were determined using the Lmfit and eBayes applications in limma.24

2.7 |. Sensitivity and specificity analysis of MIR31–5p

The sensitivity and specificity of MIR31-5p in differentiating SSA/Ps from HPs were determined using Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) statistics. The ROC curve was generated using the “roc” function in the “pROC” package of the R statistical computing language, version 3.2.1. The 95% confidence interval for the area under the curve (AUC) was estimated from 1000 bootstrap samples.

2.8 |. qPCR validation of differentially expressed miRNAs

RT-qPCR was applied to 84 of the same 108 RNAlater-stored colorectal tissues that had been analyzed previously by small RNA-seq. These 84 included 15 SSA/Ps (10 syndromic and 5 sporadic), 10 HPs, 12 adenomatous polyps (APs), 15 uninvolved from patients with SSA/Ps, 6 uninvolved from patients with HPs but not SSAPs or APs, 10 uninvolved from patients with APs but not SSA/Ps, and 16 normal colon samples. cDNA was generated from 7 ng total RNA of each sample with the Taq-Man Advanced miRNA cDNA Synthesis Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA #A28007). Ten μL qPCR reactions each included 3 μL cDNA (diluted 1/12 following the synthesis kit’s final step), the TaqMan Advanced miRNA Assay primer set (Applied Biosystems, #A25576) for each miRNA, plus TaqMan Fast Advanced Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, #4444557). PCR reactions were assembled in wells of 384-well MicroAmp Optical reaction plates (Applied Biosystems, #4309849) and run in triplicate in a Life Technologies QuantStudio 12 K Flex real-time PCR instrument using cycling conditions recommended by the manufacturer for that master mix. miRNA levels’ fold changes were determined using the ∆∆CT method, and statistical significance determined with the Mann Whitney U-test. Let-7g-5p miRNA was chosen as the reference miRNA for our PCRs’ relative quantitation based on its moderately high expression level and its lack of shift according to the prior RNA-Seq results across our sample categories. The six miRNAs examined by PCR were as follows (with their Applied Biosystems’ Assay ID designations in parentheses): MIR31-5p (478015_mir), MIR21-3p (477973_mir), MIR378A-5p (mmu482643_mir), MIR151A-3p (477919_mir), MIR135B-5p (478582_mir), and MIRLET7G-5p (478580_mir). Two miRNAs, MIR31, and MIR135B, found differentially expressed between SSA/Ps and HPs, were further examined in a new cohort of 47 FFPE samples (26 SSA/Ps and 21 HPs) using the same RT-qPCR procedure.

2.9 |. Comparison to TCGA colon cancer RNA-seq data

We compared our differentially expressed SSA/P miRNAs (FDR < 0.05, Supporting Information Tables S1 and S2) to small RNA-seq colon cancer data publically available in the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA).25 Two hundred and twelve TCGA colon cancers had both genomic aberration and CMS data available for our analysis. Of 32 differentially expressed miRNAs, only 24 could be evaluated in TCGA colon cancer data. Publically available TCGA small RNA-seq data were previously aligned to the Hg19 human reference genome and do not contain read data for seven recently identified miRNAs, or miRNAs with symbol numbers above 3000. Therefore, MIR3141, MIR3614, MIR3656, MIR3960, MIR4485, MIR4488, and MIR6089 were excluded from the analysis. MIR1299 was also excluded from the analysis because only 3 of 212 cancers had measurable read counts for this miRNA. The expression of 24 miRNAs (17 differentially expressed to paired uninvolved colon, 6 differentially expressed to HPs and 1 differentially expressed to both) was examined in 212 colon cancer small RNA-seq datasets. We compared the expression of each miRNA according to BRAF and KRAS mutation status, microsatellite instability (MSI), CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP), and CMS.

2.10 |. Pathway analysis of putative mRNA targets

To predict mRNA targets for differentially expressed miRNAs we used the TargetScanHuman prediction tool within the Ingenuity miRNA target filter (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) application.26 TargetScan predicts biological targets by searching for conserved sites in mRNAs that match the seed region of each miRNA. After identifying putative mRNA targets for each miRNA, we used our previously obtained mRNA sequencing data7 to filter for mRNAs with expression that was negatively correlated with miRNA expression. Canonical pathways were determined for all differentially expressed mRNAs (n = 5029) and mRNAs negatively correlated (n = 1390) with one or more miRNAs differentially expressed in SSA/Ps.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Small RNA distribution and abundance

Small RNA sequencing was performed on 108 prospectively obtained colon biospecimens. The mean sequence depth was 5.5 million uniquely mapped reads per sample. There were 1010 unique RefSeq small RNAs expressed in human colon (≥10 reads in one or more samples), with 95% of those RNAs representing miRNAs (653, 65%) and small nucleolar RNAs (snRNAs, 299, 30%) (Supporting Information Figure S1A). The majority of reads (84%) mapped to annotated miRNAs, with 54% of miRNA reads coming from five miRNAs MIR192, MIR21, MIR148A, MIR143, and MIR200B. The average read count for each of the 653 miRNAs across all biospecimens is shown in Supporting Information Figure S1B.

3.2 |. Differential gene expression analysis

3.2.1 |. Polyp comparisons to paired uninvolved colon

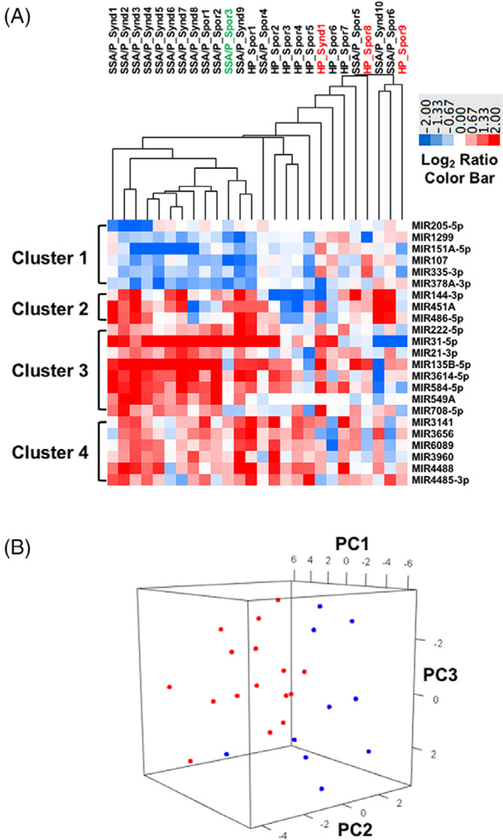

Differentially expressed small RNAs in SSA/Ps, HPs, and adenomatous polyps (APs) were determined using paired DESeq2 negative binomial statistics as part of the online Oasis DE analysis module.21 We compared 16 SSA/Ps to paired uninvolved colon and identified 23 differentially expressed (Fold ≥ 1.5, FDR < 0.05) miRNAs, 5 snRNAs and 1 piRNA (Supporting Information Table S1). Two novel miRNAs, one on chromosome 10 and one on chromosome X, were also differentially expressed in SSA/Ps using a less stringent statistical cutoff (Fold ≥ 1.4, FDR < 0.1). In contrast, when comparing 10 HPs to paired uninvolved colon, only one miRNA (MIR4488) and one piRNA (PIR020579) were differentially expressed (Fold ≥ 1.5, FDR < 0.05), and both were also differentially expressed in SSA/Ps. Hierarchical clustering and principal component analysis (PCA) of the 23 differentially expressed miRNAs across the 26 serrated polyps are shown in Figure 1A,B, respectively. Cluster 3 in the heatmap shows eight miRNAs with the largest and most consistent increases in expression in most SSA/Ps but not HPs. Cluster 1 shows a similar pattern for five downregulated miRNAs in most SSA/Ps compared to HPs. Cluster 2 identifies a subgroup of eight SSA/Ps with high expression of MIR144, MIR451, and MIR486. Cluster 4 shows six miRNAs that are similarly expressed in SSA/Ps and HPs. We also compared 14 APs to paired uninvolved colon and identified 8 differentially expressed (Fold ≥ 1.5, FDR < 0.05) miRNAs and 1 piRNA (PIR012734) (Supporting Information Table S1). Three of the eight differentially expressed miRNAs in APs were also differentially expressed in SSA/Ps. The fold change and significance of the most differentially expressed miRNAs (Fold ≥ 2, FDR < 0.05) across the three polyp types are shown in Table 1.

FIGURE 1.

Relative expression of 23 miRNAs differentially expressed in SSA/Ps across 26 serrated polyps (16 SSA/Ps and 10 HPs). A, Hierarchical clustering was performed with correlation and single linkage metrics using log2 ratios for each polyp compared to matched uninvolved colon. Four distinct miRNA gene clusters were identified. B, Principal component analysis (PCA) of the 26 polyp samples using the same log2 ratio values as in A. Principal component 1 (PC1), PC2, and PC3 accounted for 19%, 12%, and 10% of the variation observed in the gene expression data, respectively. SSA/P red and HP blue filled circles [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

TABLE 1.

miRNAs differentially expressed in SSA/Ps, APs, and/or HPs compared to paired uninvolved colon

| miRNA | SSA/P_Fold | SSA/P_FDR | AP_Fold | AP_FDR | HP_Fold | HP_FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIR31–5p | 9.14 | <0.001 | 2.82 | 0.157 | 1.98 | 0.527 |

| MIR135B-5p | 5.42 | <0.001 | 6.57 | 0.001 | 1.98 | 0.407 |

| MIR549A | 4.18 | 0.012 | 15.56 | <0.001 | 1.00 | 1.000 |

| MIR3614–5p | 2.63 | 0.006 | ‒1.32 | 0.443 | 1.78 | 0.407 |

| MIR222–5p | 2.37 | 0.018 | ‒1.23 | 0.803 | 1.48 | 0.670 |

| MIR144–3p | 2.30 | <0.001 | 1.66 | 0.409 | −2.04 | 0.407 |

| MIR584–5p | 2.18 | 0.004 | 2.07 | 0.038 | 1.67 | 0.407 |

| MIR451A | 2.10 | 0.014 | 1.32 | 0.637 | −1.16 | 0.892 |

| MIR4488 | 2.09 | 0.005 | 1.07 | 0.916 | 2.25 | 0.010 |

| MIR151A-5p | ‒2.24 | 0.015 | 1.02 | 0.939 | −1.12 | 0.870 |

| MIR205–5p | ‒3.93 | 0.011 | 1.00 | 1.000 | 1.00 | 1.000 |

Eleven, three, and one miRNA(s) was (were) differentially expressed more than twofold in SSA/Ps (n = 16), APs (n = 14), and HPs (n = 10), respectively. Values for each differentially expressed miRNA are shown across all three polyp subtypes. FDR denotes Benjamini and Hochberg false discovery rate.

3.2.2 |. Serrated polyp comparisons

Following voom normalization and lmfit and eBayes statistical analyses, we identified six miRNAs differentially expressed (Fold ≥ 1.5, FDR < 0.05) between 16 SSA/Ps and 14 HPs (Supporting Information Table S2). Similar to comparisons to paired uninvolved colon, MIR31-5p was the most differentially expressed miRNA (11-fold, FDR < 0.05) in SSA/Ps compared to HPs (Figure 2). One other miRNA (MIR615-3p) was overexpressed and four miRNAs (MIR1247-5p, MIR204-5p, MIR210-3p, and MIR375) were underexpressed in SSA/Ps compared to HPs (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Relative expression of 6 miRNAs differentially expressed in 16 SSA/Ps compared to 14 HPs. Four miRNAs were underexpressed (filled circles, fold change between −1.77 and −4.40) and two were overexpressed (filled triangles, fold change between 7.11 and 11.16) in SSA/Ps compared to HPs. Average read counts for each serrated polyp type are shown on a log scale (SSA/P - Y axis, HP - X axis)

3.2.3 |. Control colon comparisons

We compared gene expression in the uninvolved right colon of patients with SSA/Ps (n = 10, five of whom had SPS) with control right colon (n = 15) from screening colonoscopy patients with no polyps. No difference in gene expression was observed in small RNAs in uninvolved colon from patients with SSA/Ps compared to control colon from patients without polyps. In contrast, when comparing control right (n = 15) and left colon (n = 15) we identified one miRNA (MIR615-3p) differentially expressed more than 20-fold in right colon (Supporting Information Table S2).

3.3 |. Sensitivity and specificity analysis of MIR31–5p

The sensitivity and specificity of MIR31-5p in differentiating SSA/Ps from HPs were determined using a ROC curve. The AUC for the accurate classification of serrated polyps ranged from 76.9% to 100% (Supporting Information Figure S2).

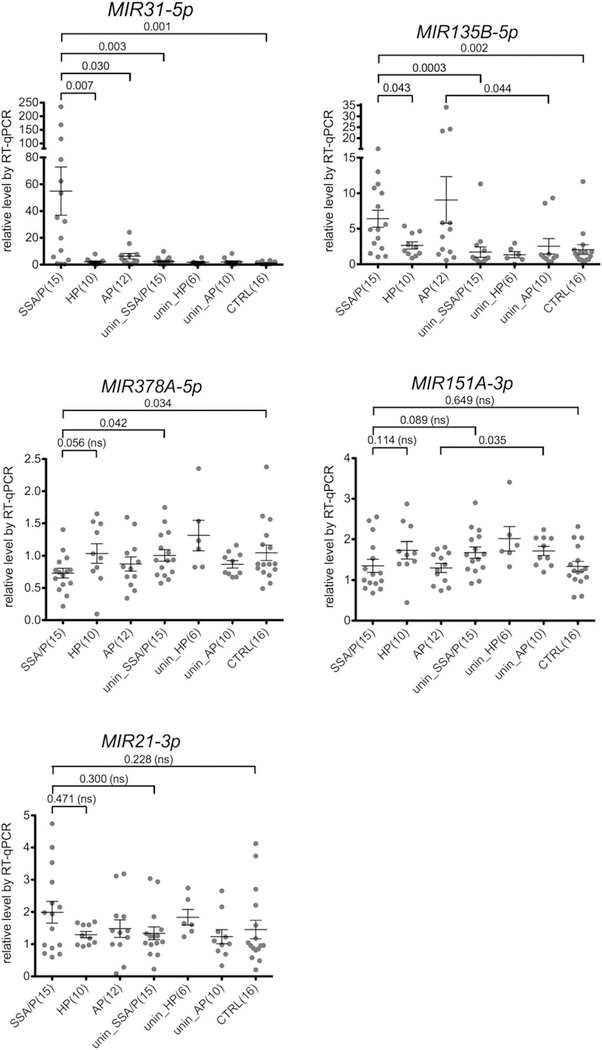

3.4 |. qPCR validation of differentially expressed miRNAs

RT-qPCR analysis of five target miRNAs (MIR31–5p, MIR21–3p, MIR378A-5p, MIR151A-3p, and MIR135B-5p) and one reference gene (MIRLET7G-5p) identified four of the five miRNAs differentially expressed in one or more comparisons (Figure 3). MIR31–5p, MIR378A-5p, and MIR135B-5p were differentially expressed in SSA/Ps compared to both uninvolved and control colon. MIR31–5p and MIR135B-5p were more highly expressed (26.2-fold and 2.4-fold, respectively) in SSA/Ps compared to HPs. Increased expression of MIR31 and MIR135B in SSA/Ps was further confirmed in a separate set of 26 SSA/P and 21 HP FFPE samples, where MIR31–5p and MIR135B-5p were overexpressed 129.2-fold and 2.5-fold in SSA/Ps compared to HPs, respectively (Supporting Information Figure S3). MIR31–5p expression was also higher (8.7-fold) in SSA/Ps compared to APs. MIR151A-3p expression was statistically lower in APs compared to uninvolved colon. MIR21–3p was not significantly differentially expressed in any comparison although showed the highest expression in the SSA/P group. A full list of fold changes and P values for all group comparisons is in Supporting Information Table S3. The correlation plots comparing the same RNAlater-stored polyp samples’ small RNA-Seq reads and RT-qPCR fold change for MIR31-5p and MIR135B-5p are shown in Supporting Information Figure S4. The R2 values for goodness of fit were 0.976 and 0.786 for MIR31-5p and MIR135B-5p, respectively.

FIGURE 3.

Expression of MIR31-5p, MIR21-3p, MIR378A-5p, MIR151A-3p, and MIR135B-5p by reverse transcription quantitative PCR analysis. Expression of each miRNA was normalized to MIRLET7G-5p expression and fold change (y axis) determined relative to the mean of control colon values. Individual sample values and the mean ± SE for each of seven sample groups (x axis) are shown. “AP” denotes adenomatous polyp and “unin” denotes uninvolved colon. The number of samples analyzed in each group is shown in parentheses. Statistical significance was calculated using the Mann-Whitney U-test. ns denotes not significant

3.5 |. Comparison to TCGA colon cancer RNA-seq data

We investigated the expression of 24 miRNAs, differentially expressed in SSA/Ps (FDR < 0.05, Supporting Information Tables S1 and S2), in 212 colon cancer miRNA datasets from the TCGA. Nine of twenty-four miRNAs (38%) differentially expressed in SSA/Ps were also differentially expressed (Fold ≥ 1.5, FDR < 0.05) in microsatellite-unstable (MSI) cancers compared to microsatellite stable cancers (Supporting Information Table S4). Eight of twenty-four miRNAs (33%) were differentially expressed in CIMP cancers compared to cancers without CIMP (Table 2). Eight and three of twenty-four miRNAs were differentially expressed in BRAF-mutant or KRAS-mutant cancers compared to cancers without mutations in BRAF or KRAS, respectively (Table 2). Five SSA/P-specific miRNAs, MIR9, MIR31, MIR615, MIR584, and MIR196B, were differentially expressed in both CIMP-positive and BRAF-mutant colon cancers.

TABLE 2.

SSA/P-specific miRNAs differentially expressed in CIMP positive, BRAF, and KRAS mutant colon cancers

| MIRNA | CIMPH (n = 37) Fold | CIMPL (n = 47) Fold | CIMP FDR | BRAF (n = 31) Fold | BRAF FDR | KRAS (n = 86) Fold | KRAS FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIR9 | ‒3.205 | ‒1.859 | <0.001 | ‒2.000 | <0.001 | ‒1.214 | 0.583 |

| MIR210 | 2.308 | 1.321 | <0.001 | 1.608 | 0.082 | 1.004 | 0.993 |

| MIR31 | 3.286 | 2.181 | <0.001 | 2.125 | 0.019 | 2.593 | <0.001 |

| MIR615 | 3.748 | ‒1.042 | <0.001 | 6.559 | <0.001 | 1.503 | 0.401 |

| MIR584 | 1.916 | 1.193 | 0.002 | 2.249 | <0.001 | 1.673 | <0.001 |

| MIR375 | 1.790 | 1.474 | 0.004 | 1.209 | 0.520 | 1.079 | 0.834 |

| MIR196b | ‒1.721 | ‒1.424 | 0.005 | ‒2.907 | <0.001 | ‒1.375 | 0.235 |

| MIR135b | 1.654 | 1.097 | 0.030 | 1.583 | 0.051 | 1.769 | <0.001 |

| MIR335 | ‒1.213 | 1.076 | 0.055 | ‒1.727 | <0.001 | ‒1.137 | 0.463 |

| MIR1247 | ‒1.101 | 1.477 | 0.541 | ‒2.955 | <0.001 | ‒1.312 | 0.423 |

| MIR204 | ‒1.030 | ‒2.232 | 0.574 | ‒2.358 | 0.023 | 1.363 | 0.503 |

Eight miRNAs showed a significant linear change in expression (Fold ≥ 1.5, FDR < 0.05) in CIMP high (H) and CIMP low (L) cancers by analysis of trend. Fold change values represent the mean expression of each miRNA in 37 CIMP-H and 47 CIMP-L cancers compared to 128 CIMP negative cancers. Eight and three miRNAs showed a significant change (DESeq2 statistics) in BRAF (n = 31) and KRAS (n = 86) mutant cancers compared to cancers without BRAF or KRAS mutations (n = 91), respectively. Four cancers had both BRAF and KRAS mutations and were excluded from BRAF and KRAS statistical analyses.

We also investigated the expression of these 24 miRNAs in the recently described CMSs of colon cancer.25 The same 212 TCGA colon cancer datasets were previously classified by CMS subtype (CMS1, n = 35; CMS2, n = 66; CMS3, n = 32; CMS4, 60; not classified, n = 19). Sixteen of twenty-four miRNAs differentially expressed in SSA/Ps were also differentially expressed (Fold ≥ 1.5, FDR < 0.05) in one or more of the 4 CMS subtypes. The majority of miRNAs (12/16 miRNAs, 75%) were differentially expressed in CMS1 compared to CMS2 colon cancers (Supporting Information Table S4). Eight of sixteen miRNAs (50%) were differentially expressed in CMS3 cancers, and nine of sixteen miRNAs (56%) were differentially expressed in CMS4 cancers (Supporting Information Table S4). The direction of fold change and overlap of each miRNA according to CMS subtype is shown in Figure 4A. All eight miRNAs differentially expressed in CMS3 cancers were also differentially expressed in CMS1 cancers. In contrast, only four of nine miRNAs differentially expressed in CMS4 cancers were also differentially expressed in CMS1 cancers.

FIGURE 4.

SSA/P-specific miRNA expression in TCGA colon cancers according to genomic aberration and consensus molecular subtype (CMS). A, Venn diagram showing the overlap in 16 miRNAs differentially expressed (Fold ≥ 1.5, FDR < 0.05) according to CMS subtype. Direction and significance of fold change expression for each miRNA were calculated by comparing CMS1, CMS3, and CMS4 subtypes to the CMS2 (conventional adenocarcinoma) subtype. MiRNAs in white and red text show the same and opposite direction of fold change in SSA/Ps compared to paired uninvolved colon, respectively. B, Hierarchical clustering of SSA/P-specific miRNA expression in 212 TCGA colon cancers according to genomic aberration and CMS subtype. Two distinct colon cancer subtype clusters (horizontal identifiers) and two miRNA gene clusters (vertical identifiers) were identified. Heatmap represents the log2 ratio of the mean for colon cancers with a specific genomic aberration or CMS subtype compared to the mean of all other cancers without that genomic aberration or all other CMS subtypes, respectively [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Hierarchical clustering of 24 miRNA genes’ expression in TCGA colon cancers by genomic aberration and CMS is shown in Supporting Information Figure S5. Only miRNAs differentially expressed in SSA/Ps were compared. Two distinct miRNA clusters are shown. In CIMP-H, MSI and CMS1 colon cancers, five miRNAs (MIR9, MIR196B, MIR204, MIR335, and MIR1247) are downregulated and five miRNAs (MIR31, MIR210, MIR375, MIR584, and MIR615) are upregulated compared to the other cancer subtypes. In contrast, these same 10 miRNAs are expressed in opposing directions in CIMP-negative, microsatellite-stable (MSS), and CMS2 colon cancers. Hierarchical clustering of only these 10 miRNAs is shown in Figure 4B. The heatmap shows that BRAF mutation is also associated with the differential expression of these 10 miRNAs and suggests that these miRNAs may be used as a gene panel to identify CMS1 colon cancers with CIMP-H, MSI, and BRAF genomic aberrations.

3.6 |. Pathway analysis of putative mRNA targets

Using the miRNA target filter application in Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) software, we compared our miRNA data with previously published messenger RNA data from SSA/Ps.7 We identified 1390 mRNA targets with expression that was negatively correlated with one or more miRNAs differentially expressed in SSA/Ps. These 1390 mRNAs were further evaluated for canonical pathway enrichment, and the top 10 pathways are shown in Table 3. Among the top pathways activated were ephrin receptor, insulin growth factor receptor, and ciliary neurotrophic factor signaling. Among the top downregulated pathways were PTEN and PPARα signaling. Enriched canonical pathways for all 5029 mRNAs differentially expressed in SSA/Ps are shown in Supporting Information Table S5. There was significant overlap in the canonical pathways identified using all differentially expressed mRNAs (5029) and only those targeted by miRNAs (1390) by IPA.

TABLE 3.

Ingenuity pathway analysis of 1390 mRNA targets differentially expressed in SSA/Ps compared to paired uninvolved colon

| SSA/P (n = 9, 1390 genes) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canonical pathways | Total genes | Gene overlap (%) | z score | P value |

| Ephrin receptor signaling | 175 | 28 (16) | 2.67 | 3.17E-06 |

| Insulin growth factor 1 signaling | 106 | 19 (18) | 2.33 | 2.33E-05 |

| Oncostatin M signaling | 34 | 9 (26) | 2.33 | 1.60E-04 |

| Ciliary neurotrophic factor signaling | 63 | 12 (19) | 2.89 | 4.05E-04 |

| Interleukin 7 signaling | 91 | 14 (15) | 3.32 | 1.31E-03 |

| NANOG stem cell signaling | 122 | 17 (14) | 3.16 | 1.32E-03 |

| ERK5 signaling | 66 | 11 (17) | 2.71 | 2.18E-03 |

| Transforming growth factor beta signaling | 87 | 13 (15) | 2.71 | 2.51E-03 |

| PPAR alpha/retinoic X receptor alpha | 180 | 21 (12) | ‒2.36 | 3.67E-03 |

| PTEN signaling | 119 | 14 (12) | ‒2.50 | 1.48E-02 |

Each of the 1390 mRNAs are targets of one or more SSA/P-specific miRNAs as determined by HumanTargetScan. P-values represent the hypergeometric test of enrichment based on the number of genes differentially expressed in the pathway compared to the total number of genes in the pathway. z score represents whether the pathway is activated (>2.0) or inhibited (<−2.0) based on the direction of fold change for each differentially expressed gene in that pathway.

4 |. DISCUSSION

SSA/Ps are pre-neoplastic colon polyps with an increased risk for advanced neoplasia and colon cancer. Historically, the neoplastic potential of SSA/Ps has not been appreciated, and SSA/Ps were often grouped with HPs due to significant histological and morphological overlap. Now that HPs (benign) and SSA/Ps (pre-neoplastic) are recognized to harbor different cancer risks, precise diagnostic tools that can inform an individual’s cancer risk and drive recommendations on frequency of surveillance are very important. This study is the first to examine small RNA expression using RNA sequencing technology in prospectively collected serrated polyps. Small RNA profiles can be used to distinguish neoplastic from benign lesions.27 We found many differentially expressed miRNAs in SSA/Ps that distinguish them from HPs including MIR31, MIR135B, MIR1247, and MIR204. The expression of MIR31 and MIR135B was further validated using RT-qPCR. We also describe for the first time the expression of SSA/P-specific miRNAs in colon cancer CMS25 and the canonical pathways likely targeted by these miRNAs.

The expression of MIR31-5p was 26 to 129-fold higher by RT-qPCR in SSA/Ps compared to HPs and 45-fold higher compared to control colon. Higher MIR31 expression occurs in advanced-stage or aggressive CRCs.28–30 MIR31 expression is associated with decreased progression-free survival (time from initiating chemotherapy until time of death or progression of disease) in metastatic CRC patients treated with anti-EGFR therapy.31 MIR31-5p promotes proliferation, tumor invasion, and cell survival in the development of CRC.29,32,33 MIR31 has also been detected in serum of patients with CRC34 and is more highly expressed in MSI-H CRCs.35 Recent studies have shown increased MIR31 expression in SSA/Ps suggesting MIR31 plays a role in the serrated pathway to colon cancer.16,36 A study by Nosho and colleagues16 showed a positive association of MIR31 expression with BRAF mutation and poor colon cancer prognosis.

To our knowledge, our study is the first to show overexpression of MIR135B in SSA/Ps. MIR135B expression is frequently elevated in colon cancer.30 Dysregulation of MIR135B has been associated with APC dysfunction that may lead to the development of hereditary or sporadic colon cancers.37,38 MIR135B promotes tumor proliferation, progression, and invasion.38 Increased MIR135B levels are found in the stools of patients with colorectal adenomas when compared to patients with normal colon mucosa.39 In one study, higher MIR135B expression in tumor tissue also correlated with improved disease-free and cancer-specific survival (time until tumor related death) in patients with rectal cancer.40

Increased MIR21 expression occurs in CRC and correlates with overall reduced survival and unfavorable prognosis.41,42 Schmitz and colleagues43 showed increased expression of MIR21 in both SSA/Ps and HPs. Evidence suggests it plays a role in cell proliferation and invasion in CRC by targeting the PTEN gene.44 Our qPCR validation of SSA/P-specific miRNA expression showed that MIR21 was elevated (1.5-fold) in SSA/Ps but was not statistically significant.

Other miRNAs differentially expressed in SSA/Ps in our study were MIR584, MIR3614–5p, and MIR378A-3p. MIR584 expression has not been previously reported in serrated polyps or serrated carcinoma. MIR3614–5p is highly expressed in cervical tumor samples and distinguishes them from normal tissue.45 No data on MIR3614–5p expression are available in colon cancer tissue or polyps. Our study is the first to show increased expression of MIR3614–5p in SSA/Ps. MIR378A-3p was significantly downregulated in SSA/Ps compared to paired uninvolved colon. Similar downregulation of MIR378 was found in CRC by microarray and RT-qPCR.46,47 Decreased expression of MIR378 was also observed in KRAS-mutant colon cancers.48

Evaluation of SSA/P-specific miRNA expression in TCGA colon cancer datasets identified many miRNAs that are differentially expressed in CIMP positive colon cancers compared to CIMP negative cancers (Table 2). The expression of MIR9, MIR31, MIR196B, MIR584, and MIR615 is highly correlated with CIMP tumor status and BRAF mutation. These changes in expression were most prominent in CIMP high (H) compared to CIMP low (L) colon cancers. However, MIR9 and MIR31 show changes in both CIMP-H and CpG island methylator phenotype-low (CIMP-L) colon cancers, suggesting a gradation in expression of these miRNAs according to the level of CpG island meth-ylation. MIR31 and MIR584 were also differentially expressed in KRAS-mutated cancers, which further supports the idea that KRAS mutations are genetic events that contribute to the serrated neoplasia pathway.

MIR9 has been reported to function in CRC as a tumor suppressor by suppressing cell migration and decreasing tumor proliferation.32,49 Decreased expression of MIR9 has been noted in colon adenomas compared to normal colon.47 Our small RNA-seq data show similarly downregulated MIR9 in adenomas (Fold < −1.8, FDR < 0.003). MIR9 expression has been associated with colon cancer patient survival.50 Methylation of the MIR9 promoter frequently occurs in colon cancer and is associated with lymph node metastasis.51

The expression of MIR196B and MIR615 is also highly correlated with MSI tumors, suggesting that these miRNAs are associated with colon cancers that develop through the serrated pathway. These findings are in agreement with two previous studies comparing miRNA expression in MSI and stable colon cancers.52,53 MIR196 has been implicated in a variety of gastrointestinal cancers, and its upregulation was noted in CRC.54 It has also been detected in plasma of patients with colon cancer.54 Our analysis of MIR196B suggests that reduced expression is associated with SSA/Ps and CIMP-positive, MSI colon cancers. Increased expression of MIR615–3p has been documented in poorly differentiated and more proximal colon cancer.55 It should be noted that MIR615 is more highly expressed in proximal than distal colon, and therefore differences in MIR615 expression among colon cancer subtypes may reflect differences in tumor location.

SSA/P-specific miRNA expression also overlapped with one or more colon cancer CMSs, most notably CMS1 (Figure 4A,B). CMS1 colon cancers have been previously described as CIMP-positive, microsatellite-unstable, and BRAF-mutated.25 MIR31, MIR196B, and MIR615 expression is highly correlated with CMS1 cancers and each of these genomic aberrations. These three miRNAs were also differentially expressed in CMS3 and CMS4 cancers, suggesting that the serrated neoplasia pathway overlaps with other cancer subtypes.

The CMS3 subtype of colon cancer is characterized by a CIMP-L pattern of DNA methylation and frequent mutations in KRAS.25 These genomic aberrations have been considered part of an alternative serrated pathway to cancer, although the precursor lesions that harbor these changes are not well defined.56 Interestingly, this alternative serrated pathway to cancer may account for the majority of serrated colon cancers and include up to 20% of all colon cancers.56 In contrast, only 15% of colon cancers are believed to develop from the classic serrated pathway that includes BRAF mutation, CIMP-H DNA methylation, and MSI though silencing of MLH1.

MIR31 is overexpressed in CMS1, CMS3, and CMS4 colon cancers compared to CMS2 cancers (Supporting Information Table S4). In fact, all eight miRNAs differentially expressed in CMS3 cancers were also differentially expressed in the same direction in CMS1 colon cancers, suggesting significant molecular overlap between these two cancer sub-types. MIR31, MIR135B, and MIR584 were overexpressed in both BRAF-mutated and KRAS-mutated colon cancers, also suggesting molecular overlap between CMS1 and CMS3 subtypes. MIR31 showed increased expression in CIMP-L cancers, also consistent with the CMS3 subtype.

CMS4 subtype colon cancers are characterized by activation of transforming growth factor beta (TGFB) signaling and upregulation of genes involved in epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT).25 These cancers have high levels of somatic copy number alterations, are MSS and have infrequent CIMP DNA methylation.25 The majority of miRNAs (8 of 11, 73%), including MIR135B, are underexpressed in CMS4 colon cancers compared to CMS2 cancers. When compared to the mean expression of all other CMS subtypes (CMS1, CMS2, and CMS3), MIR31 and MIR584 are also underexpressed in CMS4 cancers (Figure 4B). These data suggest that the miRNA profile in CMS1 colon cancers is more similar to CMS3 than CMS4 cancers.

The canonical signaling pathways affected in SSA/Ps are consistent with enhanced growth factor signaling (Table 3). Ephrin receptor and insulin-like growth factor 1 signaling are increased while PPARα and PTEN signaling are decreased, each suggesting enhanced phosphoinositide 3 kinase (PI3K) signaling in SSA/Ps. Concomitant Pten and Kras mutations in mice increase cell proliferation along the crypt-villus axis, branching of intestinal villi and the formation of HPs and sessile serrated adenomas.57 Sessile serrated adenomas from these mice also show increased levels of phosphorylated AKT, ERK, and MEK protein, suggesting increased PI3K signaling.57

Colon cancers with PI3KCA exon 20 or PTEN mutations are associated with a proximal location, BRAF mutation, MSI and are CIMP-H,58 suggesting that these cancers develop through the sessile serrated pathway. Similarly, PIK3CA exon 9 mutations are also common in proximal colon cancers but are associated with a CIMP-L phenotype and KRAS mutation,58 suggesting an alternative serrated pathway to colon cancer. These findings are consistent with the miRNA profiles and signaling pathways we have found altered in SSA/Ps. However, mutations in PIK3CA and PTEN have not been described in SSA/Ps, which warrants further research in this area.

TGFB signaling, also increased in SSA/Ps, primarily induces EMT in BRAF-mutated colon organoids but not organoids derived from traditional adenomas.59 It has been hypothesized that CMS4 subtype colon cancers may develop from SSA/Ps due to common gene signatures in TGFB signaling, matrix remodeling, and EMT pathways.60 NANOG expression is influenced by both TGFB and PI3K signaling,61,62 and the observed increase in NANOG signaling in SSA/Ps likely contributes to EMT. Overexpression of NANOG has been associated with advanced tumor stages and poor survival in colon cancer patients.63

In summary, this report provides a comprehensive analysis of miRNA gene expression in prospectively collected serrated colon polyps. We identified previously undescribed, differential expression of miRNAs in SSA/Ps but not HPs, including MIR135B, MIR378A, MIR548, MIR9, and MIR196B, suggesting that miRNAs are good predictors of serrated neoplasia. Interestingly, the majority of SSA/P-specific miRNAs are also differentially expressed in CMS1-subtype colon cancers that are CIMP-positive, BRAF-mutated, and MSI. MIR9, MIR31, and MIR196B are also differentially expressed in CMS3-subtype colon cancers, suggesting that the serrated pathway may encompass multiple colon cancer subtypes. Pathway analysis of miRNA targets suggests that activation of growth factor signaling pathways underlie serrated polyp biology. Future mechanistic and clinical studies will be required to study the significance of these miRNA profiles in colon cancer developing from SSA/Ps.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Alyssa Mills (University of Utah) for her assistance in sample collection and Dr. Stefan Bonn (German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases) for his assistance in the use of Oasis small RNA analysis software. We also thank Brian Dalley and the High Throughput Genomics Core (Huntsman Cancer Institute) for their sequencing of the RNA samples.

Funding information

National Institutes of Health, Grant/Award Number: CA191507

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of the article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Snover DC, Ahnen DJ, Burt RW, Odze RD. Serrated polyps of the colon and rectum and serrated polyposis. In: Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise ND, eds. WHO Classification of Tumors of the Digestive System Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2010:160–165. [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Brien MJ, Zhao Q, Yang S. Colorectal serrated pathway cancers and precursors. Histopathology 2015;66:49–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jass JR. Classification of colorectal cancer based on correlation of clinical, morphological and molecular features. Histopathology 2007;50:113–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Snover DC. Update on the serrated pathway to colorectal carcinoma. Hum Pathol 2011;42:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turner JK, Williams GT, Morgan M, et al. Interobserver agreement in the reporting of colorectal polyp pathology among bowel cancer screening pathologists in Wales. Histopathology 2013;62:916–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rau TT, Agaimy A, Gehoff A, et al. Defined morphological criteria allow reliable diagnosis of colorectal serrated polyps and predict polyp genetics. Virchows Arch 2014;464:663–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanth P, Bronner MP, Boucher KM, et al. Gene signature in sessile serrated polyps identifies colon cancer subtype. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2016;9:456–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delker DA, McGettigan BM, Kanth P, et al. RNA sequencing of sessile serrated colon polyps identifies differentially expressed genes and immunohistochemical markers. PLoS One 2014;9:e88367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jasperson KW, Kanth P, Kirchhoff AC, et al. Serrated polyposis: colonic phenotype, extracolonic features, and familial risk in a large cohort. Dis Colon Rectum 2013;56:1211–1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rashid A, Houlihan PS, Booker S, et al. Phenotypic and molecular characteristics of hyperplastic polyposis. Gastroenterology 2000;119:323–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boparai KS, Mathus-Vliegen EM, Koornstra JJ, et al. Increased colorectal cancer risk during follow-up in patients with hyperplastic polyposis syndrome: a multicentre cohort study. Gut 2010;59:1094–1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bushati N, Cohen SM. microRNA functions. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2007;23:175–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okugawa Y, Grady WM, Goel A. Epigenetic alterations in colorectal cancer: emerging biomarkers. Gastroenterology 2015;149:1204–1225.e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Toyota M, Suzuki H, Sasaki Y, et al. Epigenetic silencing of microRNA-34b/c and B-cell translocation gene 4 is associated with CpG island methylation in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res 2008;68:4123–4132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sells E, Pandey R, Chen H, et al. Specific microRNA-mRNA regulatory network of colon cancer invasion mediated by tissue Kallikrein-related peptidase 6. Neoplasia 2017;19:396–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nosho K, Igarashi H, Nojima M, et al. Association of microRNA-31 with BRAF mutation, colorectal cancer survival and serrated pathway. Carcinogenesis 2014;35:776–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsikitis VL, Potter A, Mori M, et al. MicroRNA signatures of colonic polyps on screening and histology. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2016;9:942–949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Slattery ML, Herrick JS, Wolff RK, et al. The miRNA landscape of colorectal polyps. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2017;56:347–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rex DK, Ahnen DJ, Baron JA, et al. Serrated lesions of the colorectum: review and recommendations from an expert panel. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:1315–1329. quiz 1314, 1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dobin A, Gingeras TR. Mapping RNA-seq reads with STAR. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics 2015;51:11.14.1–11.14.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Capece V, Garcia Vizcaino JC, Vidal R, et al. Oasis: online analysis of small RNA deep sequencing data. Bioinformatics 2015;31:2205–2207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 2014;15:550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Law CW, Chen Y, Shi W, Smyth GK. Voom: precision weights unlock linear model analysis tools for RNA-seq read counts. Genome Biol 2014;15:R29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smyth GK. Linear models and empirical bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol 2004;3:1–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guinney J, Dienstmann R, Wang X, et al. The consensus molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer. Nat Med 2015;21:1350–1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang Z, Zhang Y, Wang L. A feedback inhibition between miRNA-127 and TGFbeta/c-Jun cascade in HCC cell migration via MMP13. PLoS One 2013;8:e65256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Agretti P, Ferrarini E, Rago T, et al. MicroRNA expression profile helps to distinguish benign nodules from papillary thyroid carcinomas starting from cells of fine-needle aspiration. Eur J Endocrinol 2012;167:393–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schee K, Boye K, Abrahamsen TW, et al. Clinical relevance of micro-RNA miR-21, miR-31, miR-92a, miR-101, miR-106a and miR-145 in colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer 2012;12:505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang MH, Yu J, Chen N. Elevated microRNA-31 expression regulates colorectal cancer progression by repressing its target gene SATB2. PLoS One 2013;8:e85353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bandres E, Cubedo E, Agirre X, et al. Identification by real-time PCR of 13 mature microRNAs differentially expressed in colorectal cancer and non-tumoral tissues. Mol Cancer 2006;5:29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Igarashi H, Kurihara H, Mitsuhashi K, et al. Association of microRNA-31–5p with clinical efficacy of anti-EGFR therapy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2015;22: 2640–2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cekaite L, Rantala JK, Bruun J, et al. MiR-9, −31, and −182 deregulation promote proliferation and tumor cell survival in colon cancer. Neoplasia 2012;14:868–879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cottonham CL, Kaneko S, Xu L. miR-21 and miR-31 converge on TIAM1 to regulate migration and invasion of colon carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem 2010;285:35293–35302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang J, Huang SK, Zhao M, et al. Identification of a circulating micro-RNA signature for colorectal cancer detection. PLoS One 2014;9: e87451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sarver AL, French AJ, Borralho PM, et al. Human colon cancer profiles show differential microRNA expression depending on mismatch repair status and are characteristic of undifferentiated proliferative states. BMC Cancer 2009;9:401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ito M, Mitsuhashi K, Igarashi H, et al. MicroRNA-31 expression in relation to BRAF mutation, CpG island methylation and colorectal continuum in serrated lesions. Int J Cancer 2014;135:2507–2515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nagel R, le Sage C, Diosdado B, et al. Regulation of the adenomatous polyposis coli gene by the miR-135 family in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res 2008;68:5795–5802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Valeri N, Braconi C, Gasparini P, et al. MicroRNA-135b promotes cancer progression by acting as a downstream effector of oncogenic pathways in colon cancer. Cancer Cell 2014;25:469–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu CW, Ng SC, Dong Y, et al. Identification of microRNA-135b in stool as a potential noninvasive biomarker for colorectal cancer and adenoma. Clin Cancer Res 2014;20:2994–3002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gaedcke J, Grade M, Camps J. The rectal cancer microRNAome--microRNA expression in rectal cancer and matched normal mucosa. Clin Cancer Res 2012;18:4919–4930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schetter AJ, Leung SY, Sohn JJ, et al. MicroRNA expression profiles associated with prognosis and therapeutic outcome in colon adenocarcinoma. JAMA 2008;299:425–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shi C, Yang Y, Xia Y, et al. Novel evidence for an oncogenic role of microRNA-21 in colitis-associated colorectal cancer. Gut 2016;65: 1470–1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schmitz KJ, Hey S, Schinwald A, et al. Differential expression of micro-RNA 181b and microRNA 21 in hyperplastic polyps and sessile serrated adenomas of the colon. Virchows Arch 2009;455:49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xiong B, Cheng Y, Ma L, et al. MiR-21 regulates biological behavior through the PTEN/PI-3 K/Akt signaling pathway in human colorectal cancer cells. Int J Oncol 2013;42:219–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Witten D, Tibshirani R, Gu SG, et al. Ultra-high throughput sequencing-based small RNA discovery and discrete statistical biomarker analysis in a collection of cervical tumours and matched controls. BMC Biol 2010;8:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang GJ, Zhou H, Xiao HX, et al. MiR-378 is an independent prognostic factor and inhibits cell growth and invasion in colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer 2014;14:109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oberg AL, French AJ, Sarver AL, et al. miRNA expression in colon polyps provides evidence for a multihit model of colon cancer. PLoS One 2011;6:e20465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mosakhani N, Sarhadi VK, Borze I, et al. MicroRNA profiling differentiates colorectal cancer according to KRAS status. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2012;51:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Park YR, Lee ST, Kim SL, et al. MicroRNA-9 suppresses cell migration and invasion through downregulation of TM4SF1 in colorectal cancer. Int J Oncol 2016;48:2135–2143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Slattery ML, Herrick JS, Mullany LE, et al. An evaluation and replication of miRNAs with disease stage and colorectal cancer-specific mortality. Int J Cancer 2015;137:428–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bandres E, Agirre X, Bitarte N, et al. Epigenetic regulation of micro-RNA expression in colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer 2009;125: 2737–2743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Slattery ML, Herrick JS, Mullany LE, et al. Colorectal tumor molecular phenotype and miRNA: expression profiles and prognosis. Mod Pathol 2016;29:915–927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Balaguer F, Moreira L, Lozano JJ, et al. Colorectal cancers with microsatellite instability display unique miRNA profiles. Clin Cancer Res 2011;17:6239–6249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lu YC, Chang JT, Chan EC, et al. miR-196, an emerging cancer biomarker for digestive tract cancers. J Cancer 2016;7:650–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schee K, Lorenz S, Worren MM, et al. Deep sequencing the microRNA transcriptome in colorectal cancer. PLoS One 2013;8:e66165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bettington M, Walker N, Clouston A, et al. The serrated pathway to colorectal carcinoma: current concepts and challenges. Histopathology 2013;62:367–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Davies EJ, Marsh Durban V, Meniel V, et al. PTEN loss and KRAS activation leads to the formation of serrated adenomas and metastatic carcinoma in the mouse intestine. J Pathol 2014;233:27–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Day FL, Jorissen RN, Lipton L, et al. PIK3CA and PTEN gene and exon mutation-specific clinicopathologic and molecular associations in colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2013;19:3285–3296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fessler E, Drost J, van Hooff SR, et al. TGFbeta signaling directs serrated adenomas to the mesenchymal colorectal cancer subtype. EMBO Mol Med 2016;8:745–760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.De Sousa EMF, Wang X, Jansen M, et al. Poor-prognosis colon cancer is defined by a molecularly distinct subtype and develops from serrated precursor lesions. Nat Med 2013;19:614–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xu RH, Sampsell-Barron TL, Gu F, et al. NANOG is a direct target of TGFbeta/activin-mediated SMAD signaling in human ESCs. Cell Stem Cell 2008;3:196–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Storm MP, Bone HK, Beck CG, et al. Regulation of Nanog expression by phosphoinositide 3-kinase-dependent signaling in murine embryonic stem cells. J Biol Chem 2007;282:6265–6273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Meng HM, Zheng P, Wang XY, et al. Over-expression of Nanog predicts tumor progression and poor prognosis in colorectal cancer. Cancer Biol Ther 2010;9:295–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.