Abstract

Background:

Research across the globe highlights rights violations and abuses experienced by women and seldom are channeled toward any atrocities being experienced by men. Objectives: To find the prevalence, characteristics, and sociodemographic correlates of gender-based violence against men.

Materials and Methods:

It was a community-based, cross-sectional study using multistage random sampling in which a total of 1000 married men in the age group of 21–49 years were interviewed using modified conflict tactics scale.

Results:

In the present study, 52.4% of men experienced gender-based violence. Out of 1000, males 51.5% experienced violence at the hands of their wives/intimate partner at least once in their lifetime and 10.5% in the last 12 months. The most common spousal violence was emotional (51.6%) followed by physical violence (6%). Only in one-tenth cases, physical assaults were severe. In almost half of the cases, husband initiated physical and emotional violence. Gender symmetry does not exist in India for physical violence. Less family income, education up to middle class, nuclear family setup, and perpetrator under the influence of alcohol were identified as risk factors. Earning spouse with education up to graduation is the risk factor for bidirectional physical violence.

Conclusion:

Besides women, men are also the victims of gender-based violence. This demands the future investigation and necessary intervention on gender-based violence against men in India.

Keywords: Domestic violence, gender-based violence, intimate partner violence, men victim, risk factors, spouse violence, violence against men, women perpetrator

INTRODUCTION

Gender-based violence has been recognized as a global public health and human rights problem that leads to high rates of morbidity, mortality, depression, substance dependence, suicide, and posttraumatic stress disorder.[1,2]

India has been a male-dominant society from ages, and it is hard to believe that male can be a victim and female a perpetrator.[3] Domestic violence against men in India is not recognized by the law as well.[4] However, contrary to common belief, there are a growing number of men who are at the receiving end of harassment and face psychological and physical abuse by women.[5,6,7]

As there are scarce research data available, therefore, this study was carried out:

To find out the prevalence, characteristics, and reasons of violence against males

To determine the sociodemographic correlates of violence.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was funded by ICMR and was completed over a period of 1 year (2012–2013). Ethics clearance was taken from the institutional ethical committee.

Study population

This was a community-based, cross-sectional study, and the rural household was taken as study unit. All the study participants were married men, aged 21–49 years. Minimum legal age of marriage in India is 21 years for boys. Married men older than 49 years were excluded to minimize the recall bias and to avoid the heightened sensitivity about the discussion of sexual matters in this older age group.

Sample size

The sample size was calculated by taking the prevalence (p) of any type of domestic violence in married males of age group 21–49 years to be 33%, design effect 1.5, and relative precision (d) 11% at 95% confidence level.[7] By applying formula, n = 1.5* (z)2 p (1 – p)/d2, the sample size was calculated to be 967. Final sample size considered for the study was 1000 males.

Sampling technique

District Rohtak was taken purposively. We used multistage random sampling. Two community health centers (CHCs) were randomly selected out of five. Among the selected CHCs, ten villages were randomly selected. From each village, 100 households were selected. The youngest married male was interviewed to maintain the privacy, if a household had two or more eligible married males.

The interview was carried out by the two recruited trained field investigators. Informed written consent was taken from all the participants. The inclusion criteria were (a) married males 21–49 years and (b) resident of the area for 5 years and the exclusion criteria were (a) who refused to give consent and (b) could not be contacted on three consecutive visits to their households.

Study tools

All interviews were done face to face by a trained male interviewer. In the entire survey, privacy was maintained. Rapport has been maintained with the participants before interview by telling them the purpose of the study, by taking only one member from one household, and by assuring them the full confidentiality of their responses. We used a standardized pretested, semi-structured questionnaire.

Physical, sexual, emotional violence was measured using the National Family Health Survey-3 (NFHS-3) domestic violence questionnaire which in turn based on modified conflict tactics scale (alpha = 0.86).[8,9] Socioeconomic status was calculated using Pareekh scale.[10] Bidirectional physical violence indicates that violence is perpetrated by both partners. However, it does not indicate that the frequency and severity are the same between both partners. Severe physical violence denotes that physical violence leads to any type of physical injury to the victim.

Statistical analysis

We combined and analyzed data with SPSS version 20 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Percentages, means, and standard deviation (SD), Pearson's Chi-square test, and McNemar's test were used. The level of significance was fixed at <0.05.

RESULTS

The study achieved full response rate; 1000 households were approached for 1000 participants. The study subjects were interviewed among which majority (38.4%) belonged to the age group >40 years (SD = 3.31). More than one-third (38.7%) of the study subjects were engaged in farming followed by self-business (22.9%). The majority (40.2%) of the subjects had studied up to higher secondary followed by the middle class (19.3%). More than half (58.3%) of the subjects belonged to joint family. Half of the subjects (50.l%) had yearly total family income between 50,000–100,000.

The total prevalence of gender-based violence was found to be 524 (52.4%) among males [Table 1].

Table 1.

Prevalence of gender based violence among men (n=1000)*

| Perpetrator of violence | Ever experienced | In last 12 months |

|---|---|---|

| Any female | 524 (52.4) | 105 (10.5) |

| Spouse | 515 (51.5) | 85 (8.5) |

| Female other than spouse | 42 (4.2) | 5 (0.5) |

*Multiple responses

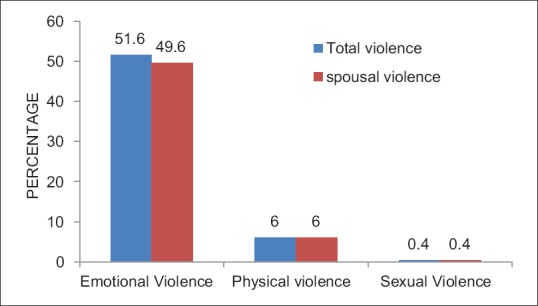

The majority (51.6%) of the subjects experienced emotional violence followed by physical (6%), then sexual violence (0.4%) by any female. The overall prevalence of emotional, physical, and sexual spousal violence is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Type of violence among male and perpetrator of the violence

Out of 60 males, 25 (2.5%) experienced physical violence in the last 12 months. The most common form of physical violence was slapping (98.3%) and the least common was beaten by weapon (3.3%). Only in one-tenth cases (seven males), physical assaults were severe. In all cases, spouse was responsible for the physical violence.

Among victims of emotional violence, 85% were criticized, 29.7% were insulted in front of others, and 3.5% were threatened or hurt. Out of 516 victims, 20 (3.9%) experienced it in last 12 months.

Out of 1000 respondents, only four (0.4%) had experienced sexual violence, out of which only one respondent experienced it in the last 12 months. Only one female physically forced her spouse to have sexual intercourse and three physically forced to perform any sexual act with her against his will.

Unemployment of the husband at the time of violence was the major reason (60.1%) for violence followed by arguing/not listening to each other (23%) and addiction of perpetrator (4.3%). Uncontrolled anger, ego problem, etc., accounted for rest of the cases.

Table 2 shows the factors which were significantly associated with gender-based violence Caste and socioeconomic status were not found significantly associated with male violence. Earning spouse with education up to graduation significantly increased (n = 60) risk of bidirectional physical violence.

Table 2.

Association of various factors with violence against men (N=1000)

| Violence not present (%) | Violence present (%) | Pearson Chi-square and P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Income status of men | |||

| Monthly income | |||

| <1000 | 162 (39.2) | 251 (60.8) | χ2=19.784, P<0.001 |

| >1000 | 314 (53.5) | 273 (46.5) | |

| 2. Male education status | |||

| Studied up to middle (8th class) | 146 (36.9) | 250 (63.1) | χ2=30.271, P<0.001 |

| Above middle | 330 (54.6) | 274 (45.4) | |

| 3. Alcoholic status of perpetrator | |||

| Alcohol | 2 (8.7) | 21 (91.3) | Yates χ2=14.285, P<0.001 |

| Not alcoholic | 474 (48.5) | 503 (51.5) | |

| 4. Type of family | |||

| Nuclear | 167 (40) | 250 (60) | χ2=16.355, P<0.001 |

| Joint | 309 (53) | 274 (47) |

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of gender-based violence/domestic violence in the present study (52.4%) was less as found by Sarkar et al. (India) where 98% men had suffered domestic violence. This could be due to the difference in methodology and sample selection, and more so, only six males were interviewed from Haryana. For later study, nonrandomized 1650 husbands mainly from upper middle class and middle class were interviewed between the ages of 15 and 49 years from all over India using a schedule adapted from WHO multicountry study on husband's health and domestic violence, which contains 14 items for emotional and 8 items for economic violence. In the present study, economic violence was not measured and only two items for emotional violence were taken.[7] Estimated numbers of incidents of domestic violence in England and Wales during 2012–2013 reported that 4.4% of men had experienced domestic abuse in the last year which is much lower than present study (10.5%); this might be because former estimates are based on people reporting actions against them perceived as crimes.[11] Hence, crime estimates are likely to significantly underestimate the real picture of domestic violence and mainly represent physical violence.

The prevalence of spouse/intimate partner violence (51.5%) in the present study was found to be higher than data collected for domestic violence under partner abuse state of knowledge project (PASK) from the U.S., Canada, and the U.K. (19.3%).[12] This might be because of different methodology and the wider range of participants (students, married, and unmarried participants); however, in the present study, only married male between ages 21–45 years included. The literature reviewed by Shuler (CA, United States) revealed that 1.3 men per 1000 were victims of intimate partner violence each year.[13] Incidence is higher than the present study (8.2%) due to the fact that present study was community-based and while literature review cited included all type of studies (community-based, hospital-based, from police record, etc.). The change in developing India can also be not denied.

The trend of different form of violence in the present study is almost similar to the PASK (80% emotional abuse and 0.2% sexual violence) but different from that reported by Sarkar et al., in which physical violence (25.2%) was more common than emotional (22.2%) and sexual violence (17.7%).[7,12] This might be due to the different methodology for considering violence. Tjaden and Thoennes (U.S. Department of Justice) reported ever physical intimate partner violence in 7.4% and 0.9% in the previous 12 months.[14] These results are almost similar to our study (6% and 2.5%). Lövestad and Krantz (Sweden) did a cross-sectional population-based study using random sampling in which 173 men and 251 women of age 18–65 were interviewed using conflict tactics scale. In this study, the incidence of physical violence was much higher (11%) than the present study (0.9%).[15] NFHS-3 and Nadda et al. (Haryana) found much higher physical violence 35% and 26.9%, respectively, against women this reflecting that Indian women are much less physically aggressive than Indian men. Gender symmetry does not exist in India for physical violence.[8,16]

Sarkar et al. found slapping was the most common (98.3%) form of physical violence similar to the present study.[7] In contrast to PASK where about one-third of physical assaults were severe, in the present study, in only one-tenth (6 males), physical assaults were severe.[12] This might be because Indian women use physical violence very rarely and chances of physical violence because of self-defense and out of fear cannot be ruled out. In half cases (46%), physical violence was bidirectional and initiated by the husband, similar to Daniel et al.[17]

Unemployment (60.1%) or less family income (<1000 rps) and addiction of the perpetrator (4.3%) were also found to be major and statistically significant reason for gender-based violence; these results are similar to given by PASK and Nadda et al. (Haryana).[12,18] Arguing and not listening to each other (22.7%) was also the common reason for male abuse similar to PASK and Corry et al.[12,19]

Victims educated up to middle class and living in a nuclear family setup were significantly at higher risk than others for violence. This might be because, in India, joint family act as a cushion in case unemployment of any member and uncontrolled anger. It was found that earning spouse with education up to graduation significantly increased risk of bidirectional physical violence, thus consolidating the fact suggested by Kumar that, when woman becomes aware of her rights and economically independent, she tries to change the power dynamics.[20] The present study shows gender-based violence is beyond the boundaries of caste and socioeconomic status of men.

CONCLUSION

Domestic violence act in India is for women only. The present study shows that men are also the victims of violence at the hand of women. Hence, necessary amendments in favor of men experiencing domestic violence should also be incorporated.

Limitations

Assessments were based on self-report, and chances of recall biases were therefore likely to underestimate the true prevalence of violence. Chances of women's physical violence, motivated by self-defense, and fear cannot be ruled out.

Financial support and sponsorship

The study was funded by Indian Council of Medical Research.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organisation. The Third Milestones of a Global Campaign for Violence Prevention Report. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. [Last accessed on 2018 May 11]. Available from: http://www.who.int/violenceprevention/events/17_07_2007/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campbell JC. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet. 2002;359:1331–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sawant ST. Place of the woman in Indian society: A brief review. J Hum Soc Sci. 2016;21:21–5. [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005. [Last accessed on 2018 May 11]. Available from: https://www.indiankanoon.org/doc/542601/

- 5.Domestic Violence against Men. San Francisco: [Last updated on 2018 Jun 06; Last accessed on 2018 May 11]. Available from: https://www.en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Domestic_violence_against_men . [Google Scholar]

- 6.Men's Rights Movement in India. San Francisco: [Last updated on 2018 May 04; Last accessed on 2002 Jul 09]. Available from: https://www.en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Men%27s_rights_movement_in_India . [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarkar S, Dsouza R, Dasgupta A. Domestic Violence against Men – A Study Report by Save Family Foundation. New Delhi, India: Save Family Foundation; 2007. [Last accessed on 2018 May 12]. Available from: https://www.ipc498a.files.wordpress.com/2007/10/domestic-violence-against-men.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), 2005-06 Domestic Violence: India. Vol. 1. Mumbai: International Institute for Population Sciences; 2007. [Last accessed on 2018 May 11]. International Institute for Population Sciences and Macro International. Available from: http://www.measuredhs.com/pubs/pdf/FRIND3/15Chapter15.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 9.Straus MA, Mickey EL. Reliability, validity, and prevalence of partner violence measured by the conflict tactics scales in male-dominant nations. Aggress Violent Behav. 2012;17:463–74. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar N, Gupta N, Kishore J. Kuppuswamy's socioeconomic scale: Updating income ranges for the year 2012. Indian J Public Health. 2012;56:103–4. doi: 10.4103/0019-557X.96988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Government Statistics on Domestic Violence. Estimated Prevalence of Domestic Violence- England and Wales 1995-2011. Dewar Research. 2014. Feb, [Last accessed on 2018 May 11]. Available from: http://www.dewar4research.org/DOCS/websiteGovtStatsonDV1995-2013.pdf .

- 12.Hamel J. Facts and statistics on domestic violence at-a-glance. DV Research. [Last accessed on 2018 May 11]. Available from: https://www.domesticviolenceresearch.org/domestic-violence-facts-and-statistics-at-a-glance/

- 13.Shuler AS. Male victims of intimate partner violence in the United States: An examination of the review of literature through the critical theoretical perspective. Int J Crim Justice Sci. 2010;5:163–73. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Full Report of the Prevalence, Incidence, and Consequences of Violence against Women. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice; 2000. [Last accessed on 2018 May 11]. Available from: https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/183781.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lövestad S, Krantz G. Men's and women's exposure and perpetration of partner violence: An epidemiological study from Sweden. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:945. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nadda A, Malik JS, Rohilla R, Chahal S, Chayal V, Arora V, et al. Study of domestic violence among currently married females of Haryana, India. Indian J Psychol Med. 2018;40:534–9. doi: 10.4103/IJPSYM.IJPSYM_62_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whitaker DJ, Haileyesus T, Swahn M, Saltzman LS. Differences in frequency of violence and reported injury between relationships with reciprocal and nonreciprocal intimate partner violence. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:941–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.079020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nadda A, Malik JS, Bhardwaj AA, Khan ZA, Arora V, Gupta S, et al. Reciprocate and nonreciprocate spousal violence: A cross-sectional study in Haryana, India. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019;8:120–4. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_273_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corry CE, Fiebert MS, Pizzey E. Controlling Domestic Violence against Men. Colorado: United States of America; 2002. [Last accessed on 2018 May 11]. Available from: http://www.familytx.org/research/Control_DV_against_men.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar A. Domestic violence against men in India: A perspective. J Hum Behav Soc Environ. 2012;22:290–6. [Google Scholar]