Abstract

Background:

Pregnancy and motherhood are natural processes and considered to be full of positive experiences. However, for various reasons many women end up dying during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period. Improving maternal health and reducing maternal mortality have been prioritized in several international declarations and national policies.

Objectives:

The objective of the study is to assess delays, cause, and its contributing factors related to maternal deaths in rural Varanasi.

Methodology:

Verbal and Social Autopsy have been done for each maternal death occurred between April 2015 and March 2016 in four randomly selected blocks of rural Varanasi. The “3 Delay Model” and “Pathway analysis” concept was used in collection and analysis of data through in-depth interview of three people (family member, neighbor, and a health worker) for each maternal death. Cause of death and delays was identified by two reviewers (obstetrician) independently.

Results:

In almost half of the autopsied cases two different delays were found, and in one-third case, only one delay was found. Direct obstetric cause found in more than half (54%) cases. Hemorrhage and anemia were found major direct and indirect obstetric cause, respectively. Other causes identified were sepsis (direct), jaundice, and meningitis. A number of social, behavioral, and cultural factors were identified, that had been contributed to different delays related to the maternal deaths.

Conclusions:

First delay was present in most of (90%) cases. Nonbiological (social, behavioral, and cultural) and health service factors were also identified in this study.

Keywords: Delay, maternal mortality, social autopsy, verbal autopsy

INTRODUCTION

Pregnancy is a natural process in the reproductive age of any women. However, for various reasons many women end up dying during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period. India has a huge toll of maternal deaths, with 50,000 deaths in 2013, which constituted 17% of the global burden of maternal mortality.[1] It has achieved a significant decline in the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) from 892 maternal deaths/100,000 live births in 1972-76-178 in 2010–2012. Nevertheless, the country is still far away from reducing it to 109 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births, which are the millennium development goal five targets for the country.[2] Every 7 min a maternal death is occurring leading to 77,000 Indian women dying each year (National Family Health Survey-3 [NFHS-3]). Most maternal death in India are concentrated in 7 states (Assam, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, Rajasthan Uttarakhand, and Uttar Pradesh). Uttar Pradesh has the 2nd highest MMR among seven states which is 292 (UP).[2] Therefore, for further reduction of MMR, it is important to understand about DELAYS and ASSOCIATED FACTORS responsible for maternal death.

METHODOLOGY

Uttar Pradesh is surrounded by Uttarakhand and Nepal in North, Bihar, and Jharkhand in the East, Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh in South and Rajasthan, Delhi, Himachal Pradesh, and Haryana in the West. The majority of the state's population lives in rural area, and the economy is predominantly agricultural. The sex ratio of Uttar Pradesh is 912 which is 918 in rural and 894 in urban (census 2011), whereas of Varanasi is 913.

After obtaining permission from Institute of Ethics Committee, a cross-sectional study was conducted. The data of total maternal death in 1 year (April 01, 2015–March 31, 2016) were obtained from CMO office, Varanasi. Although it was tried to find out more maternal death through community informants, ASHA and ANM of selected blocks we did not find any more maternal death. It may be possible that few cases were missed due to underreporting. Hence, selection bias may have occurred through the way we have selected the study sample (limitation). There were 48 reported maternal deaths in eight blocks (Araziline, Baragaon, Chiraigaon, Cholapur, Harhua, Kashi Vidyapeeth, Pindra, and Sewapuri) of Varanasi during the last 1 year as per report of Health Department, CMO office of Varanasi. Out of which, 4 blocks (due to resource constraints) were selected randomly (using random no. Table). Thus about half of the total maternal deaths of Varanasi, i.e., 22 (Cholapur-7, Kashi Vidyapeeth -5, Chiraigaon-5, and Harhua-5) has been covered in this study.

Verbal and social autopsies were conducted for all the selected 22 cases. First informed written consent was taken from each respondent. The respondents were selected based on their presence with the deceased women during the development of complications, transportation to health facility, treatment, referral, and death. We first approached the respondents in person, explained the objectives of the study to them, and fixed an appointment with them for an interview based on their availability and convenience. The power dynamics of familial relationships may have influenced the data in the form of dominant responses from the elder family members, as we included more than one relative or family member as respondents in the interviews. However, we tried to create such an environment during the interviews in which all respondents provided their views and no participant dominated the responses. Along with the researcher, a social worker was involved in data collection. The interviews were conducted in the houses of the deceased women. All interviews lasted between 40 and 60 min. In order to elucidate or elaborate some responses, follow-up interviews and phone calls were made in some cases. We examined a subset of narratives by discussing them with the informants to check the accuracy and ensure the quality of data. To protect the informants from harm in terms of the distressing nature of interviews, we took informed consent, assured them about anonymity, and told them that they were free to withdraw at any time or refuse to answer any specific question; we also arranged debriefing of informants after conducting interviews. The standard WHO definition of maternal death was used for this study.

Community-based maternal death review and INDEPTH Network social autopsy tool were used for the study.[3] For social autopsy, we did not find any validated tool till the study period. Hence, a pilot study was done with the open-ended questionnaire of “IN DEPTH NETWORK” in one of the neighboring blocks (not in the study area). Based on this pilot study, we modified some question in the tool based on the experiences of the field to address the overall research question. We used the “expert opinion” method including expert of OBG, sociology, and community medicine for validation of the tool. To collect social autopsy data, we conducted in-depth interview of family members/relatives, one of the nearest neighbor of the deceased and one health worker either ASHA or ANM. Thus, for each death, three persons were interviewed.

Information on background characteristics of the deceased women and their families were obtained through structured questions. In addition, open-ended questions were asked to collect the facts related to the complications that led to death and the care-seeking behavior for those complications. This qualitative part of the study was an attempt to elicit the perceptions of respondents about the factors and conditions surrounding the maternal deaths. The interviews were conducted after 2 months to up to 1 year of maternal death. The social autopsy questions were pretested in one of the neighboring blocks (not in the study area) and modified accordingly before its use in the present study.

The respondents were selected based on their presence with the deceased women during the development of complications, transportation to health facility, treatment, referral, and death. The power dynamics of familial relationships may have influenced the data in the form of dominant responses from the elder family members, as we included more than one relative or family member as respondents in the interviews. All interviews lasted between 40 and 60 min. In order to elaborate some responses, follow-up interviews and phone calls were made in 8 cases. We examined a subset of narratives by discussing them with the informants to check the accuracy and ensure the quality of data. The standard WHO definition of maternal death was used for this study.[4]

Data were entered into Excel then transferred to SPSS version 17 (trial version, IBM, New York, USA) for statistical analysis. Descriptive analysis of the general characteristics, i.e., sociodemographic profile, was done, and whenever applicable, proportions were calculated. The probable cause of death was decided after reviewing the completed verbal autopsy formats by two obstetricians who independently assigned the cause of death based on available information recorded in questionnaires' related to the history, events, and symptoms. In 20 cases, the diagnosis of the two obstetricians matched. In two cases, there was disagreement, so we consulted a third obstetrician to review the format and make the most probable diagnosis. This was considered as final diagnosis. All in-depth interviews were recorded and transcribed in full text. Thorough familiarity with the responses was gained by listening and re-listening all the recordings several times separately and matching with the respective text transcribed. To maintain anonymity, the verbal autopsies of individual cases of maternal deaths were assigned code number from 1 to 22. The transcribed material was categorized and analyzed through Pathway to Survival conceptual framework.[3] Here, this concept was used to identify and organize modifiable social, cultural, and health system factors affecting antenatal care, health-care access and utilization. Then “three delays” framework of Thaddeus and Maine[5] was applied to organize the findings of this study. A delay was supposed to have occurred if in the perception of the reviewers, the delay seemed to have partially contributed to the death or if the delay was “avoidable” by some action by either the caregiver or health professional. Based on the review of the case history, a subjective assessment of the different levels of delay being a critical determinant of outcome was made. Delay was defined based on the model proposed by Thaddeus and Maine:

1st delay: Delay in deciding to seek care

2nd delay: Delay in reaching the health-care facility

3rd delay: Delay in receiving care at health-care facility.

Limitations

This study has identified the maternal deaths by going through the government record, so it might be possible that few cases were missed due to under reporting

Since the interviews were conducted from 8 weeks after death to 1 year of death, recall bias cannot be denied. To minimize this bias, more than one respondent were interviewed (3 respondent per case)

Sample size (22) is very small, so the result cannot be generalized for all maternal deaths, but the nature of the result can be confidently generalized to the rural Varanasi because of a similar socioeconomic and cultural milieu.

RESULTS

The mean age of the women in the sample of identified maternal deaths was 23 years (±5.5) with a minimum of 16 years and maximum of 35 years. Around 45.5% of women were illiterate, and 13.6% of women belonged to the nuclear family. According to the modified B G Prasad's classification, of 22, 3 (13.6%) were in social Class II, 6 (27.3%) were in social Class III, 9 (40.9%) were in social Class IV, and 4 (18.2%) were in social Class V. About 95.5% were Hindu and only 4.5% were Muslim. Of 22, 8 (32%) were from Scheduled Caste/Scheduled Tribe category, 13 (52%) were from Other Backward Class, and only 1 (4%) was from General Category.

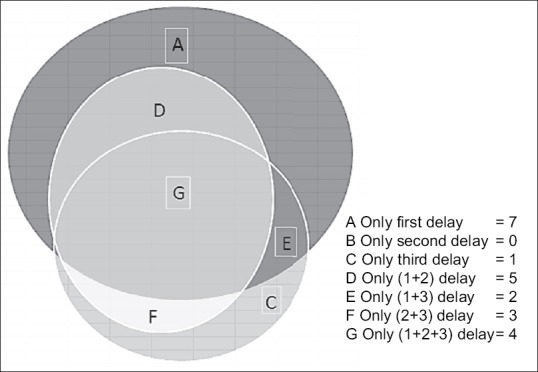

Most of the deaths were associated with multiple levels of delay, i.e., with an interaction of at least two of the three levels of delay. In 8 of the 22 cases, only one level of delay was identified; 10 women faced two different levels of delay; three cases were subjected to all three levels of delay. After identifying the contribution of each delay separately, it was found that 1st delay was present in 18 out of 22 cases (81.8%), 2nd delay was present in 12 out of 22 (54.5%) cases, and 3rd delay was present in 10 out of 22 (45.5%) cases. There was combination of delays also, as 5 deaths faced 1st and 2nd delays, 3 deaths faced 2nd and 3rd delays, 2 deaths faced 1st and 3rd delays and 4 deaths faced all the three delays (1st +2nd +3rd delays) [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Venn diagram (Maternal death autopsied)

Cause of death

Of total 22 death identified, 12 (54.5%) deaths were as a result of direct obstetric causes and 10 were as a result of indirect obstetric cause. Among direct obstetric causes, “Haemorrhage” was the leadings cause accounting for 9 out of 12 (75%) direct obstetric death. Eight of these nine hemorrhages were postpartum hemorrhage, and one was antepartum hemorrhage (Abruptio placentae). Two of the total 12 (16.7%) direct obstetric deaths were caused by “Sepsis” and both were spontaneous home deliveries conducted by their relatives [Table 1]. Indirect obstetric deaths accounted for 10 out of total 22 (45.5%) identified maternal deaths and the predominant indirect cause was due to “Anaemia” which was found in 6 (60%) cases. One case died due to “Jaundice” and one case died due to” Meningities.” In the remaining two deaths, reviewer (obstetrician) was unable to make any diagnosis on the basis of given information. Further analysis of deaths by specific causes revealed that 8 deaths were due to postpartum hemorrhage, out of which 6 (75%) occurred within 24 h of delivery and 2 (25%) deaths occurred after 24 h of delivery.

Table 1.

Cause of death identified through verbal autopsy of maternal death in four blocks of Varanasi

| Cause of death | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Direct obstetric cause | 12 (54.5) |

| APH | 1 (8.3) |

| PPH | 8 (66.7) |

| Sepsis | 2 (16.7) |

| Eclampsia | 1 (8.3) |

| Indirect obstetric cause | 10 (45.5) |

| Anemia | 6 (60) |

| Jaundice | 1 (10) |

| Meningitis | 1 (10) |

| Unknown | 2 (20) |

PPH: Postpartum hemorrhage, APH: Antepartum hemorrhage

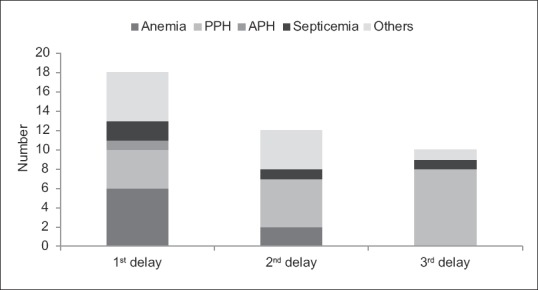

Cause of death in relation with the different level of delay

We have analyzed the contribution of (proportions) different cause of death for each level of delay. It was found that anemia was the most common cause of death where 1st level of delay was identified. Similarly, PPH was found most common cause of death where 2nd or 3rd level of delay was identified [Figure 2]. As jaundice, meningitis, and eclampsia was cause of death in only one case separately, so we have clubbed them together in “other causes.” Of 22 identified maternal deaths, only two (9.1%) had taken full ANC care [Table 2].

Figure 2.

Distribution of cause (proportion) of maternal death with respect to different levels of delay in four blocks of Varanasi (April 1, 2015–March 31, 2016)

Table 2.

Status of antenatal care service utilization by deceased mother in four selected blocks of Varanasi

| Variables | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Place of registration (n=22) | |

| Not registered | 1 (04.5) |

| Private | 1 (04.5) |

| Government | 20 (91.0) |

| Time of registration (n=21) | |

| 1st trimester death | 6 (28.57) |

| 2nd trimester death | 9 (42.85) |

| 3rd trimester death | 6 (28.57) |

| Number of ANC visit (n=22) | |

| 0 | 1 (4.5) |

| 1 | 2 (9.1) |

| 2 | 5 (27.7) |

| 3 | 10 (45.45) |

| ≥4 | 4 (18.18) |

| TT injection (n=22) | |

| 0 | 1 (4.5) |

| 1 | 5 (22.72) |

| 2 | 16 (72.72) |

| Number of IFA tablets consumes (n=22) | |

| 0 | 1 (4.5) |

| <100 | 16 (72.72) |

| ≥100 | 5 (22.72) |

| Full ANC (4 ANC visit, at least ITT, IFA for ≥100 days (n=22) | |

| Yes | 2 (9.1) |

| No | 20 (90.9) |

ANC: Antenatal care, ITT: One tetanus toxoid, IFA: Iron folic acid, TT: Tetanus toxoid

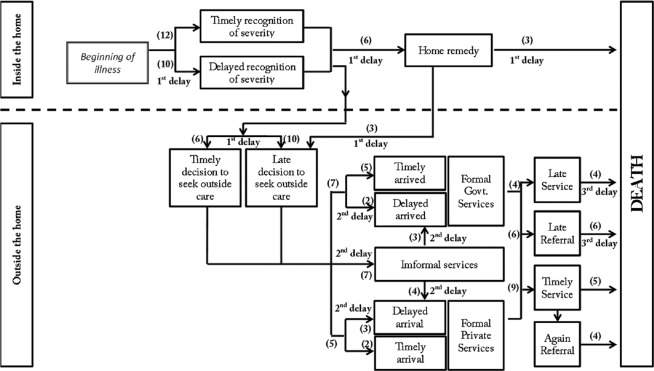

Pathway analysis of maternal death

After understanding the severity of the symptom the 1st step taken by 6 out of 22 cases (27.3%) was application of some “Home Remedy,” in seven (31.8%) cases they 1st consulted a Quack, in only 4 (18.2%) cases they 1st consulted government doctor and in 5 (22.7%) cases they consulted 1st a private doctor. Among 11 out of 22 (50%) cases, the history revealed that they visited two or more than two centers before death, in eight cases (36.4%) they visited one center before death and in three cases (13.6%) they died at home without visiting any center. Among total 22 identified maternal deaths, 10 (45.5%) deaths occurred at private facility, 8 deaths (36.4%) occurred on the way during transportation, 3 deaths (13.6%) occurred at home, and 1 death (4.5%) occurred at government facility [Table 3 and Figure 3].

Table 3.

Distribution of important sensitive points, identified through pathway analysis of identified maternal deaths

| Variables (important checkpoints of identified maternal death) | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| First activity carried out by family, relatives, neighbor, after understanding the severity of symptom (n=22) | |

| Home remedy | 6 (27.3) |

| Consulted quack | 7 (31.8) |

| Private facility | 5 (22.7) |

| Government facility | 4 (18.2) |

| Number of center visited before death (n=22) | |

| 0 | 3 (13.6) |

| 1 | 8 (36.4) |

| ≥2 | 11 (50.0) |

| Place of death (n=22) | |

| Home | 3 (13.6) |

| On the way | 8 (36.4) |

| Private hospital | 10 (45.5) |

| Government hospital | 1 (4.5) |

Figure 3.

Pathway analysis of 22 identified maternal death in four blocks of rural Varanasi (April 01, 2015–March 31, 2016)

DISCUSSION

Maternal death is often a consequence of a long and complex chain of delays, and only in few cases death can be attributed to a specific event.[6] Anyone delay could be fatal to a women with obstetric complications. Contrary to the common belief, that women do not seek care and die in the community, we identified the women who initially intended to deliver at home, but tried to get assistance once a complication occurred. The problems encountered in trying to do so, revealed major obstacle in access to appropriate care within an acceptable time.

After identifying the contribution of each delay separately, it was found that 1st delay was present in 81.8% of cases, 2nd delay was present in 54.5% cases, and 3rd delay was present in 45.5% of cases. The above result differs from those in a study of Madhya Pradesh,[7] in which 1st delay was present in 50% of cases, 2nd delay in 95.5% of cases, and 3rd delay in 59% of cases. It seems that local sociocultural practices are playing important role in affecting the different level of delays in different areas. Hence, the steps to reduce these delays should be in such a way that it is socially acceptable, affordable, and accessible.

This study found that 54.5% of death was as a result of direct obstetric cause and 45.5% due to indirect obstetric cause. Similar finding was also found in a study (in 2011) of Madhya Pradesh.[8] In 2008[9] Similar sequence of cause of death was also found in a study in four different states of India.

The analysis of the relation between different causes of death with different level of delays showed that to cut short death due to anemia, we have to focus on 1st delay, i.e., “Patient factor.” It includes proper antenatal care and making the community more aware of danger sign. Similarly, it was thought earlier that to minimize the death due to PPH, we have to only improve facility care, but this study showed that there are different patient factor, i.e., level 1 delay factor which are also contributing an important role in causing death due to PPH [Figure 2]. Full ANC care (i.e., at least 4 ANC visit, at least one tetanus toxoid, and iron-folic acid (IFA) tablets or syrup taken for 100 or more days) found only in 9.1% of cases, which was similar to NFHS-4 data which have reported 8.6% in rural Varanasi. The two most common reasons behind the low-level compliance of consumption of IFA tablets were found out in this study were lack of knowledge of requirement of iron in pregnancy and the symptoms (nausea and vomiting) associated with its use. Therefore, there seems a need to motivate all pregnant women of rural Varanasi, for better compliance of IFA tablets consumption.

Finding obtained by using pathway to survival conceptual framework [Figure 3] was found in accordance with the study of Gambia[9] where it was found that 1st place to seek care was TBA in 28% of cases, from dispensary in 28% of cases, from health center in 34% of cases and 9% from hospital.

Almost 50% of cases the history revealed that they visited two or more than two centers before death, which is very much close to the finding of a study (in 2011) by Kalter et al.[10] This indicates the need of proper awareness and accurate referral system.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank and United Nations Population Division. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014. WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank, United Nations Population Division. Trends in Maternal Mortality: 1990 to 2013- Estimates. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Special Bulletin on Maternal Mortality in India 2010-2012. New Delhi: Office of the Registrar General of India; 2013. Registrar General of India. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Källander K, Kadobera D, Williams TN, Nielsen RT, Yevoo L, Mutebi A, et al. Social autopsy: INDEPTH network experiences of utility, process, practices, and challenges in investigating causes and contributors to mortality. Popul Health Metr. 2011;9:44. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-9-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organisation. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. 10th ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thaddeus S, Maine D. Too far to walk: Maternal mortality in context. Soc Sci Med. 1994;38:1091–110. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90226-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barnes-Josiah D, Myntti C, Augustin A. The “three delays” as a framework for examining maternal mortality in Haiti. Soc Sci Med. 1998;46:981–93. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)10018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jat TR, Deo PR, Goicolea I, Hurtig AK, San Sebastian M. Socio-cultural and service delivery dimensions of maternal mortality in rural central India: A qualitative exploration using a human rights lens. Glob Health Action. 2015;8:24976. doi: 10.3402/gha.v8.24976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dikid T, Gupta M, Kaur M, Goel S, Aggarwal AK, Caravotta J, et al. Maternal and perinatal death inquiry and response project implementation review in India. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2013;63:101–7. doi: 10.1007/s13224-012-0264-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cham M, Sundby J, Vangen S. Maternal mortality in the rural Gambia, a qualitative study on access to emergency obstetric care. Reprod Health. 2005;2:3. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kalter HD, Salgado R, Babille M, Koffi AK, Black RE. Social autopsy for maternal and child deaths: A comprehensive literature review to examine the concept and the development of the method. Popul Health Metr. 2011;9:45. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-9-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]