Abstract

Objective

The meta-analysis was conducted to assess the effectiveness and safety of intravenous administration of dexmedetomidine for cesarean section under general anesthesia, as well as neonatal outcomes.

Materials and methods

We searched PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and the China National Knowledge Infrastructure database for relevant randomized controlled trials (RCTs) about the application of intravenous dexmedetomidine under general anesthesia for cesarean section. RevMan 5.3 was used to conduct the meta-analysis of the outcomes of interest.

Results

Eight RCTs involved 376 participants were included in this study. The meta-analysis showed that the mean blood pressure at the time of intubation (weighted mean difference [WMD]: −15.67, 95% CI: −21.21, −10.13, P<0.00001), skin incision (WMD: −12.83, 95% CI −20.53, −5.14, P=0.001), and delivery (WMD: −11.65, 95% CI −17.18, −6.13, P<0.0001) in dexmedetomidine group were significantly lower than that in the control group. The heart rate (HR) at the time of intubation (WMD: −31.41, 95% CI −35.01, −27.81, P<0.00001), skin incision (WMD: −22.32, 95% CI −34.55, −10.10, P=0.0003), and delivery (WMD: −19.07, 95% CI −22.09, −16.04, P<0.00001) were also lower than that in control group. For neonatal parameters, no differences existed in umbilical blood gases at delivery, and Apgar scores at 1 minute (WMD: −0.12, 95% CI −0.37, 0.12, P=0.33) and 5 minutes (WMD: −0.17, 95% CI −0.13, 0.46, P=0.27) among two groups.

Conclusion

Intravenous administration of dexmedetomidine could efficiently attenuate the maternal cardiovascular response during cesarean section, without affecting Apgar score of the neonate.

Keywords: dexmedetomidine, general anesthesia, cesarean section, cardiovascular response, meta-analysis, randomized controlled trial

Introduction

The implementation of obstetric anesthesia has become increasingly challenging as we are facing more and more complex and critical patients in clinical practice. Under these circumstances, effective management of anesthesia is of great importance to ensure the safety of the mother and fetus during a cesarean section. Although neuraxial anesthesia has been widely used for cesarean section, it was not feasible for patients with certain contraindications. Besides, severe cardiopulmonary complications, incomplete nerve block, and emergencies during cesarean section could further result in difficulties of neuraxial anesthesia strategies.1 For those cases with serious comorbidities, general anesthesia has become the first choice for cesarean delivery in terms of certain circumstance. Various anesthetics have been used during cesarean section under general anesthesia, some of which have the potential to cause neonatal respiratory depression.2–4 Tracheal intubation and surgical stimulation could cause significant hemodynamic changes. Opioids were usually used to attenuate the hemodynamic response, but could result in certain critical adverse reactions, such as respiratory depression of the neonate which limited the application of the anesthetics before delivery.3

As a highly selective alpha-2-adrenoceptor agonist, dexmedetomidine was widely used for sedation, anxiolysis, and analgesia effects during general or local anesthesia.5,6 It reduced the requirement of anesthetics and cardiovascular responses associated with invasive anesthesia procedure, decreased surgical stress, characterized by little effect on respiration.7 Recently, intravenous application of dexmetetomidine has been used in addition to spinal anesthesia8,9 and as an adjuvant for cesarean section.10–14

Clinical researchers have already investigated the efficacy and safety of intravenous dexmedetomidine for cesarean section under spinal anesthesia,8,15 but the application of dexmedetomidine for cesarean section under general anesthesia is still controversial. Therefore, we conducted a meta-analysis to investigate the efficacy of intravenous applications of dexmedetomidine on perioperative maternal hemodynamics and neonatal outcome during cesarean section under general anesthesia.

Materials and methods

Literature search

Two investigators independently searched databases, including PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and China National Knowledge Infrastructure through the month of November 2018, without language limitation. The search strategy included a combination of free text words and medical subject headings terms as follows: “Dexmedetomidine”, “Adrenergic α-Agonists”, “cesarean section”, “C-section”, “cesarean delivery”, “abdominal delivery”, “general anesthesia” and “Randomized controlled trial”. We also obtained additional articles by reviewing the references of relevant articles to prevent the missing randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Articles were considered for further analysis which reported the dexmedetomidine used for the induction of general anesthesia for cesarean section.

Inclusion criteria

Eligible criteria: 1) original and independent RCTs, 2) involved participants ≥18 years; 3) American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status I or II, 4) intravenous dexmedetomidine was used for cesarean section under general anesthesia, and 5) outcomes included maternal mean arterial pressure (MAP) and heart rate (HR), umbilical blood gas parameters and Apgar scores.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two reviewers independently assessed the trails complied with the eligibility criteria, extracted data and recorded the trial characteristics, while another reviewer checked the extracted data. The following information was collected: the first author, publication year, sample size, ASA physical status, details of dexmedetomidine administration, and interest of outcomes and anesthetic drug administration in each period of anesthesia (Table 1).

Table 1.

Details of included studies

| Author | Country | Age (years) | Sample size | Details of the interventions | Target outcomes | Anesthetics used during surgery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| El-Tahan et al, 201210 | Saudi Arabia | 18–35 | 17/17 | Dex group: 0.1 mL/kg/h of solution containing dexmedetomidine 4 µg/mL continuously IV; control group: 0.9% normal saline 0.1 mL/kg/h IV | 4, 5 | Induction: propofol, suxamethonium; maintenance: sevoflurane, NO, rocuronium, fentanyl; emergence: diclofenac, paracetamol. |

| Eskandr et al, 201811 | Egypt | 18–40 | 20/20 | Dex group: dexmedetomidine bolus 1 µg/kg, 0.4 µg/kg/h continuously IV; control group: equivalent volume of 0.9% normal saline IV | 5 | Induction: propofol, rocuronium; maintenance: sevoflurane, fentanyl; emergence: morphine. |

| Kart and Hanci, 201812 | Turkey | 18–42 | 30/30 | Dex group: dexmedetomidine 1 µg/kg; control group: equivalent volume of 0.9% normal saline IV | 1, 2, 3 | Induction: propofol, rocuronium; maintenance: sevoflurane, fentanyl; emergence: levobupivacaine; |

| Yu et al, 201513 | China | 22–37 | 17/18 | Dex group: dexmedetomidine bolus 0.6 µg/kg, 0.4 µg/kg/h continuously IV; control group: equivalent volume of 0.9% normal saline IV | 2, 3, 4, 5 | Induction: propofol, remifentanil, cisatracurium; maintenance: sevoflurane, propofol, remifentanil, fentanyl, midazolam; emergence: not mentioned. |

| Song et al, 201720 | China | 21–35 | 30/30 | Dex group: dexmedetomidine 0.8 µg/kg/h continuously IV; control group: 0.9% normal saline 0.8 µg/kg/h continuously IV | 1, 2, 3 | Induction: propofol, rocuronium; maintenance: propofol, remifentanil; emergence: not mentioned. |

| Deng and Wu, 201521 | China | 21–35 | 20/20 | Dex group: dexmedetomidine 0.8 µg/kg/h continuously IV; control group: 0.9% normal saline 0.8 µg/kg/h continuously IV | 1, 2, 3, 4 | Induction: propofol, rocuronium; maintenance: sevoflurane, propofol, remifentanil; emergence: not mentioned. |

| Wu et al, 201522 | China | 22–37 | 17/17 | Dex group: dexmedetomidine bolus 0.6 µg/kg, 0.4 µg/kg/h continuously IV; control group: equivalent volume of 0.9% normal saline IV | 1, 3, 4, 5 | Induction: propofol, remifentanil, cisatracurium; maintenance: propofol, remifentanil, atracurium, fentanyl, midazolam; emergence: not mentioned. |

| Shi et al, 201823 | China | Not available | 32/41 | Dex group: dexmedetomidine bolus 0.4 µg/kg, 0.4 µg/kg/h continuously IV; control group: equivalent volume of 0.9% normal saline IV | 4, 5 | Induction: propofol, cisatracurium; maintenance: propofol, fentanyl, midazolam; emergence: not mentioned. |

Notes: 1) MAP and heart rate (HR) at the time of intubation; 2) MAP and HR at the time of skin incision; 3) MAP and HR at the time of delivery; 4) PH, pO2 and pCO2 of umbilical blood gas; 5) Apgar scores at 1 minute and 5 minutes after delivery.

Abbreviations: Dex, dexmedetomidine; MAP, mean arterial pressure; NO, nitrous oxide.

The risk of bias of individual studies was assessed independently by using the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool.16 The following aspects were assessed for each included study: 1) adequate sequence generation, 2) allocation concealment, 3) blinding, 4) incomplete outcome data, 5) selective reporting, and 6) other potential sources of bias. If there was any divergence, disagreements were resolved by the corresponding author when the two authors failed to reach an agreement.

Data analysis

Review manager version 5.3 statistical software17 (The Cochrane Collaboration, The Nordic Cochrane Center, Copenhagen, Denmark) was used to pool and analyze the studies. Risk ratios and 95% CI were calculated for dichotomous data, and weighted mean differences (WMD) for continuous data. The heterogeneity χ2 was calculated as the I2 for the variation due to heterogeneity, and I2 values >50% were considered significant. Data were analyzed with a fixed effects model which were not significantly homogeneous (I2 <50%), otherwise, a random-effect model was followed.16 Estimated means and SDs were derived from the sample sizes, medians, range, and the IQRs using the formulas described by Luo et al18 and Wan et al19 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The relevant calculation formulas of SD and mean.

Results

Study selection

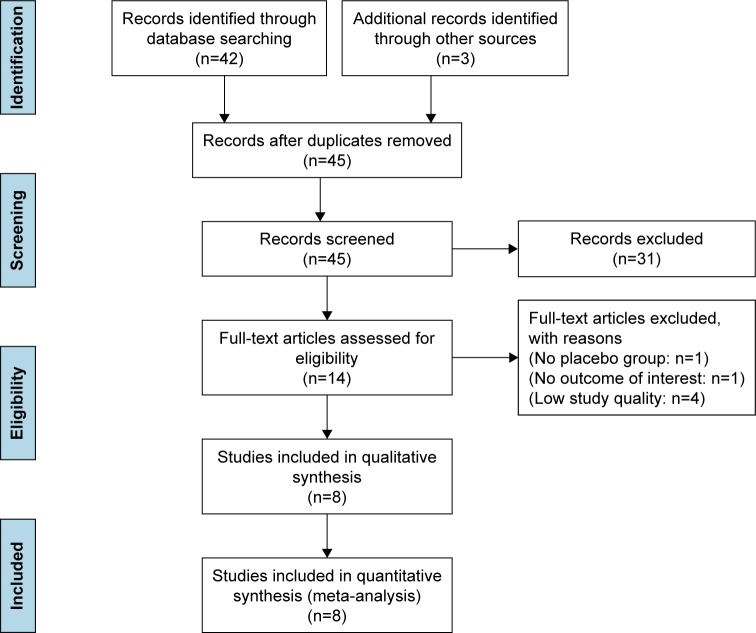

Initially, 45 articles were included in accordance with our search strategy. A total of 31 publications were excluded at this stage by reading titles and abstracts and analyzing and evaluating them for exclusion criteria. The remaining 14, potentially relevant, publications were selected for further analyses. Finally, only 8 RCTs10–13,20–23 involving 376 participants were included. Details of the trials are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of the study selection process.

Study characteristics

Published RCTs were considered for inclusion when they involved intravenous application of dexmedetomidine for cesarean section under general anesthesia. All included studies investigated the effectiveness and safety of intravenous application of dexmedetomidine as an adjuvant for cesarean section, compared with controlled interventions (IV normal saline or other placebos). At least one of the following outcomes was reported: maternal MAP and HRs, venous umbilical blood gas (pH, pO2, pCO2, etc.) and Apgar scores.

Risk of bias within studies

Four trials10,13,20,22 were adequate for sequence generation, and unclear sequence generation was reported in one trial.23 Only one study23 had high risk for allocation concealment. Blinding of participants was unclear in two trials,22,23 and two trials12,20 had high risk of bias. Adequate blinding of outcome assessment was found in four trials,10,13,21,22 while it was inadequate in two trials.12,23 Seven trials10–12,20–23 had low risk of incomplete outcome data, and there was also a low risk of reporting bias in seven trials.11–13,20–23 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Risk of bias summary.

Notes: “+”, low risk; “−”, high risk; “?”, unclear risk.

Maternal outcome

All researchers measured MAP and HR at the different time points during perioperative period. Four trials12,20–22 measured the MAP and HR at the time of intubation. Statistical heterogeneity was found in MAP (I2=57%), but not in HR (I2=0%). Therefore, the random effects model and fixed effects model were performed for the meta-analysis. The results suggested that the MAP (WMD: −15.67, 95% CI −21.21, −10.13, P<0.00001) and HR (WMD: −31.41, 95% CI −35.01, −27.81, P<0.00001) were significantly lower in the dexmedetomidine group than that in control group at the time of intubation. Four studies12,13,20,21 recorded the MAP and HR at the time of skin incision. Statistical heterogeneity existed in both MAP (79%) and HR (90%). The random effects model was applied. The results showed that the levels of MAP (WMD: −12.83, 95% CI −20.53, −5.14, P=0.001) and HR (WMD: −22.32, 95% CI −34.55, −10.10, P=0.0003) in the dexmedetomidine group were also lower than that in control group. Five RCTs12,13,20–22 analyzed the levels of delivery MAP and HR. Obvious heterogeneity was detected in both MAP (I2=63%) and HR (I2=84%). The random effects model was performed for the meta-analysis. The results revealed that the delivery MAP (WMD: −11.65, 95% CI −17.18, −6.13, P<0.0001) and HR (WMD: −19.07, 95% CI −22.09, −16.04, P<0.00001) were also lower than that in control group. Maternal outcomes were shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Maternal outcome parameters. (A) MAP at the time of intubation; (B) HR at the time of intubation; (C) MAP at the time of skin incision; (D) HR at the time of skin incision; (E) MAP at the time of delivery; (F) HR at the time of delivery.

Abbreviations: MAP, mean arterial pressure; HR, heart rate.

Four studies10,13,21,22 assessed the effectiveness of dexmedetomidine on the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV). Although two trials13,22 suggested there was no difference in the incidence of nausea or vomiting between dexmedetomidine and placebo. Researchers found that the dexmedetomidine group had a significantly lower incidence of nausea and vomiting than that in the control group, which reported nausea and vomiting for the first postoperative hour.10,21 As shown in the study by Wu et al,22 dexmedetomidine was significantly more effective than the placebo for the prevention of perioperative shivering (P<0.05).

Furthermore, studies demonstrated that the complications, such as maternal bradyarrhythmia and hypotension, were not reported during cesarean section.1,5 Likewise, in the trail of Eskandr et al,11 no patients required ephedrine but four required atropine (three in dexmedetomidine group, one in control group); however, these differences were not statistically significant. However, Yu et al13 described one patient in the dexmedetomidine group and two patients in the control group were treated with ephedrine.

Neonatal outcome

Five trials10,13,21–23 measured umbilical venous blood gas parameters (pH, pO2, and pCO2) at delivery. No significant differences existed between pH values (WMD: −0.00, 95% CI −003, 0.02, P=0.83), pO2 (WMD: −0.20, 95% CI −1.04, 0.64, P=0.64) and pCO2 (WMD: −0.10, 95% CI −1.91, 1.72, P=0.92) in both groups (Figure 5). Statistical heterogeneity was found both in pH (I2=61%) and in pCO2 (I2=72%), but not in pO2 (I2=14%). Five studies2,9,10,19,23 assessed Apgar scores at 1 and 5 minutes after delivery. No statistical heterogeneity was existed among groups (I2=0%). Therefore, the random effects model was performed for the meta-analysis. There were no differences between groups in Apgar scores at 1 minute after delivery (WMD: −0.12, 95% CI −0.37, 0.12, P=0.33). Statistical heterogeneity was existed among groups (I2=56%) when comparing the Apgar scores at 5 minutes after delivery and the fixed effects model was performed. The results suggested the Apgar scores at 5 minutes after delivery (WMD: −0.17, 95% CI −0.13, 0.46, P=0.27) were similar among groups (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Neonatal outcome: Umbilical blood gas parameters. (A) pH of umbilical blood gas; (B) pO2 of umbilical blood gas; (C) pCO2 of umbilical blood gas.

Figure 6.

Neonatal outcome: Apgar scores. (A) Apgar scores at 1 minute after delivery; (B) Apgar scores at 5 minutes after delivery.

Discussion

Cesarean section is a common surgical method and has gained popularity in daily clinical practices.11 In addition, surgery without sufficient anesthetics could increase the risk of intra-operative awareness24 and cardiovascular responses. However, excessive administration of anesthetics may result in fetal asphyxia,2–4 as well as hemodynamic depression of the mother.

As a highly selective alpha-2-adrenergic receptor, dexmedetomidine could reduce the release of norepinephrine via stimulating the alpha-2-adrenergic receptor on the presynaptic membrane and block the transmission of pain signals. This effect could also inhibit the sympathetic nerves’ activity, leading to lower hemodynamic response, as well as the effects of sedation and anti-anxiety. Recent evidence showed that cardiovascular responses to endotracheal intubation and surgical procedures may be modulated by dexmedetomidine.24–27 Dexmedetomidine has been shown to effectively reduce the requirements of perioperative anesthetics.26–28 Furthermore, dexmedetomidine blunted hemodynamic fluctuation and improved the recovery quality.29 The results of our meta-analysis were consistent with these previous observations, indicating that the administration of dexmedetomidine could significantly maintain the maternal hemodynamic stability by decreasing stress response during cesarean section. Unfortunately, dexmedetomidine could cause bradycardia in clinical trial by inhibiting sympathetic activity, especially in patient with increased vagal tone or history of atrioventricular block. Only three included studies10,11,21 have recorded the incidence of bradycardia, it appears that the incidence in the dexmedetomidine group was higher than that in control group, but no statistical significance was observed. Bradycardia was always transient and reversible; however, it was also worthy of timely attention for leading to serious adverse consequences.

A PRISMA-compliant meta-analysis indicated that dexmedetomidine, regardless of administration modes, was associated with lower incidence of PONV.30 The antiemetic effect could be related to the inhibited catecholamine though enhanced parasympathetic tone, as well as to decreased perioperative opioid consumption. Only one included study22 demonstrated the occurrence of perioperative shivering in patients undergoing cesarean section. Thus, more studies are still needed to justify whether the application of dexmedetomidine could reduce the incidence of shivering.

By far, multicenter clinical research about the intravenous application of dexmedetomidine for cesarean delivery under general anesthesia is still lacking. A clinical trial suggested that infusion of dexmedetomidine could not affect the fetus’ safety.14 The secondary results of our analysis indicated no significant difference in umbilical blood gas parameters and Apgar scores at 1 and 5 minutes among two groups. Although dexmedetomidine could reach the fetus directly through the placenta, significant respiratory depression and sedation in the fetus were not apparent.13,14,31 In addition, the fat-soluble properties of dexmedetomidine result in high retention of dexmedetomidine in the placenta, thus reducing the dosage of dexamethasone transferred to the fetus.23 The presynaptic alpha-2-adrenergic receptor of the nucleus ceruleus in the brain accounted ‘conscious sedation’ effect of dexmedetomidine. Different from other sedative drugs, such as midazolam and propofol, which acts on the brain cortex to produce unnatural sedation effects; dexmedetomidine produced a sedative hypnosis effect through acting on the subcortical system. Since the function of the wake-up system is still retained, this sedative hypnosis effect is similar to the state of natural sleep that can be eliminated by verbal or physiological stimulation. Due to this special ‘conscious sedation’ effect, newborns are naturally able to be ‘woken up’ and cry by physiological stimuli after delivery.

A meta-analysis of randomized trials about the application of intravenous administration of dexmedetomidine for obstetric anesthesia have emphasized its safety under spinal anesthesia15 and the effect on fetal outcomes.32 We conducted this meta-analysis mainly to evaluate the efficacy and safety of intravenous application of dexmedetomidine during cesarean section under general anesthesia. The present study suggested that intravenous administration of dexmedetomidine could efficiently attenuate the maternal cardiovascular response during cesarean section, without affecting the Apgar score of the neonate.

Limitations

However, there were still several limitations in our study. Firstly, the study had small sample size, as only eight studies were involved in this meta-analysis, which could affect the reliability of this study. Additionally, the strategy of study design, such as dosage and administration modes of dexmedetomidine and other combined anesthetics, could also lead to substantial heterogeneity across the studies. Furthermore, we have not assessed its effects on uterine contraction, intraoperative awareness, postoperative analgesia and other adverse effects due to lack of certain information. Therefore, further studies with larger sample sizes and multi-indicators are warranted to determine the beneficial effects in this meta-analysis.

Conclusion

In summary, the results of our study suggested that intravenous application of dexmedetomidine could efficiently attenuate maternal cardiovascular response during cesarean section, without affecting the Apgar score of the neonate.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by grants from the Tangshan Science and Technology Innovation Team Project (18130220A). The authors also thank Professor Jian Zhang for the English language editing.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Huang CJ, Fan YC, Tsai PS. Differential impacts of modes of anaesthesia on the risk of stroke among preeclamptic women who undergo caesarean delivery: a population-based study. Br J Anaesth. 2010;105(6):818–826. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeq266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maghsoudloo M, Eftekhar N, Ashraf MA, Khan ZH, Sereshkeh HP. Does intravenous fentanyl affect Apgar scores and umbilical vessel blood gas parameters in cesarean section under general anesthesia? Acta Med Iran. 2011;49(8):517–522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mattingly JE, D’Alessio J, Ramanathan J. Effects of obstetric analgesics and anesthetics on the neonate: a review. Paediatr Drugs. 2003;5(9):615–627. doi: 10.2165/00148581-200305090-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Draisci G, Valente A, Suppa E, et al. Remifentanil for cesarean section under general anesthesia: effects on maternal stress hormone secretion and neonatal well-being: a randomized trial. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2008;17(2):130–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mantz J, Josserand J, Hamada S. Dexmedetomidine: new insights. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2011;28(1):3–6. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0b013e32833e266d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hall JE, Uhrich TD, Barney JA, Arain SR, Ebert TJ. Sedative, amnestic, and analgesic properties of small-dose dexmedetomidine infusions. Anesth Analg. 2000;90(3):699–705. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200003000-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zeng X, Jiang J, Yang L, Ding W. Epidural dexmedetomidine reduces the requirement of propofol during total intravenous anaesthesia and improves analgesia after surgery in patients undergoing open thoracic surgery. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):3992. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-04382-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cortegiani A, Accurso G, Gregoretti C. Should we use dexmedetomidine for sedation in parturients undergoing caesarean section under spinal anaesthesia? Turk J Anaesth Reanim. 2017;45(5):249–250. doi: 10.5152/TJAR.2017.0457812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang J, Han Z, Zhou H, Wang N, Ma H. Effective loading dose of dexmedetomidine to induce adequate sedation in parturients undergoing caesarean section under spinal anaesthesia. Turk J Anaesth Reanim. 2017;45(5):260–263. doi: 10.5152/TJAR.2017.04578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.El-Tahan MR, Mowafi HA, Al Sheikh IH, Khidr AM, Al-Juhaiman RA. Efficacy of dexmedetomidine in suppressing cardiovascular and hormonal responses to general anaesthesia for caesarean delivery: a dose-response study. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2012;21(3):222–229. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eskandr AM, Metwally AA, Ahmed AA, et al. Dexmedetomidine as a part of general anaesthesia for caesarean delivery in patients with pre-eclampsia: a randomised double-blinded trial. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2018;35(5):372–378. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kart K, Hanci A. Effects of remifentanil and dexmedetomidine on the mother’s awareness and neonatal Apgar scores in caesarean section under general anaesthesia. J Int Med Res. 2018;46(5):1846–1854. doi: 10.1177/0300060518759891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu M, Han C, Jiang X, et al. Effect and placental transfer of dexmedetomidine during caesarean section under general anaesthesia. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2015;117(3):204–208. doi: 10.1111/bcpt.12389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li C, Li Y, Wang K, Kong X. Comparative evaluation of remifentanil and dexmedetomidine in general anesthesia for cesarean delivery. Med Sci Monit. 2015;21:3806–3813. doi: 10.12659/MSM.895209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bao Z, Zhou C, Wang X, Zhu Y. Intravenous dexmedetomidine during spinal anaesthesia for caesarean section: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Int Med Res. 2017;45(3):924–932. doi: 10.1177/0300060517708945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The Nordic Cochrane, Centre TCC. Review Manager (Rev Man) Version 5.3. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luo D, Wan X, Liu J, Tong T. Optimally estimating the sample Mean from the sample size, median, mid-range, and/or mid-quartile range. Stat Methods Med Res. 2018;27(6):1785–1805. doi: 10.1177/0962280216669183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, Tong T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14(1):135. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song Q, Song HX, Bian HC, Gao CJ. Effects of preoperative infusion of dexmedetomidine on stress response and hemodynamics of patients undergoing cesarean section under general anesthesia. Chin J Woman Child Health Res. 2017;28(9):1154–1156. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deng C, Wu W. Effect of dexmedetomidine in suppressing cardiovascular and hormonal responses to general anaesthesia for caesarean delivery. Sichuan Med J. 2015;36(2):191–194. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu X, Yuan DX, Han CB, et al. Efficacy of dexmedetomidine in cesarean section under general anesthesia. Jiangsu Med J. 2015;41(20):2397–2400. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shi W, Huang BW, Luo YW, et al. Effect of dexmedetomidine on endotracheal intubation response during general anesthesia in pregnant women undergoing cesarean section. J Guangdong Med Univ. 2018;36(1):100–103. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pandit JJ, Andrade J, Bogod DG, et al. 5th National Audit Project (NAP5) on accidental awareness during general anaesthesia: summary of main findings and risk factors. Br J Anaesth. 2014;113(4):549–559. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeu313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gaszyński T, Czarnik K, Łaziński L, et al. Dexmedetomidine for attenuating haemodynamic response to intubation stimuli in morbidly obese patients anaesthetised using low-opioid technique: comparison with fentanyl-based general anaesthesia. Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther. 2016;48(5):275–279. doi: 10.5603/AIT.a2016.0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.El-Shmaa NS, El-Baradey GF. The efficacy of labetalol vs dexmedetomidine for attenuation of hemodynamic stress response to laryngoscopy and endotracheal intubation. J Clin Anesth. 2016;31:267–273. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2016.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumari K, Gombar S, Kapoor D, Sandhu HS. Clinical study to evaluate the role of preoperative dexmedetomidine in attenuation of hemodynamic response to direct laryngoscopy and tracheal intubation. Acta Anaesthesiol Taiwan. 2015;53(4):123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.aat.2015.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schnabel A, Meyer-Frießem CH, Reichl SU, Zahn PK, Pogatzki-Zahn EM. Is intraoperative dexmedetomidine a new option for postoperative pain treatment? A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pain. 2013;154(7):1140–1149. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rani P, Hemanth Kumar VR, Ravishankar M, et al. Rapid and reliable smooth extubation – comparison of fentanyl with dexmedetomidine: a randomized, double-blind clinical trial. Anesth Essays Res. 2016;10(3):597–601. doi: 10.4103/0259-1162.186605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jin S, Liang DD, Chen C, Zhang M, Wang J. Dexmedetomidine prevent postoperative nausea and vomiting on patients during general anesthesia: a PRISMA-compliant meta analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medicine. 2017;96(1):e5770. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000005770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bilotta F, Rosa G. ‘Anesthesia’ for awake neurosurgery. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2009;22(5):560–565. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e3283302339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang J, Zhou H, Sheng K, Tian T, Wu A. Foetal responses to dexmedetomidine in parturients undergoing caesarean section: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Int Med Res. 2017;45(5):1613–1625. doi: 10.1177/0300060517707113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]