Abstract

Magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles and near infrared (NIR) fluorescent single-walled carbon nanotube (SWNT) form heterostructured complexes that can be utilized as multimodal bioimaging agents. Fe catalyst-grown SWNT were individually dispersed in water by encapsulation with oligonucleotide DNA, d(GT)15, and enriched using a 0.5 T magnetic array. The resulting nanotube complexes show distinct NIR fluorescence, Raman scattering, and visible/NIR absorbance features, corresponding to the various nanotube species. AFM and Cryo-TEM images show DNA-encapsulated complexes composed of a ~3 nm particle attached to a carbon nanotube on one end. X-ray diffraction (XRD) and superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID) measurements reveal that the nanoparticles are primarily Fe2O3 and superparamagnetic. The Fe2O3 particle-enriched nanotube solution has a magnetic particle content of ~35 wt.%, a magnetization saturation of ~56 emu/g, and a magnetic relaxation timescale ratio (T1/T2) of approximately 12. These complexes have a longer spin-spin relaxation time (T2 ~ 164 ms) than typical ferromagnetic particles due to the smaller size of their magnetic component, while still retaining SWNT optical signatures. Macrophage cells that engulf the DNA-wrapped complexes were imaged using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and NIR mapping, demonstrating that these multifunctional nanostructures could potentially be useful in multimodal biomedical imaging.

Introduction

Single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWNT) exhibit unique electrical and optical properties, including large Raman scattering cross-sections, near infrared (NIR) fluorescence, and UV/visible/NIR absorption.1–9 Each optical transition corresponds to a specific nanotube species that is identified by a chirality vector, (n, m) that defines the chirality of SWNT as they are conceptually rolled-up graphene sheets.2 The optical properties of SWNT make them appealing as biological sensors and imaging contrast agents since their NIR photoluminescence (PL) lies within the “biological window” (700 to 1300 nm) where absorption, scattering and auto-fluorescence by tissues, blood and water are minimized.10,11 Note that the PL of SWNT is observed only when they are individually dispersed.12,13 Previous studies have shown that carbon nanotubes can be individually suspended using surfactants,12,13 polymers,14 proteins,3,15 phospholipids,16 and DNA oligonucleotides10,17–19 in aqueous solution, making them biocompatible as well. We have shown that SWNT wrapped by DNA oligonucleotides are engulfed by living cells through endocytosis and remain fluorescent without significant photo-bleaching10 suggesting that they can be used as viable biomedical imaging agents.19

Iron oxide nanoparticles have been studied extensively as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contrast agents and mediators for cancer magnetic hyperthermia.20–23 In MRI, iron oxide particles induce de-phasing of proton spin by energy exchange between the atomic nuclei, resulting in the decrease of spin-spin relaxation time, T2 and thus creating the image contrast. These magnetic nanoparticles have much higher relaxivities than Gd(III)-chelating molecules, which are often used for spin-lattice relaxation time T1-weighted imaging.20,22,24 Dextran-coated iron oxide particles are less toxic than pristine iron oxide particles due to biocompatible surface coating, and thus have an order of magnitude higher lethal dose level (LD50).23 We have demonstrated that iron oxide nanoparticles can be used as potential contrast agents for magnetomotive optical coherence tomography (MM-OCT).25,26 A modulated external magnetic field induces the motion of the magnetic particles, thereby modifying the overall scattering properties. By locking onto the modulation frequency and by comparing the scattering signals when the field is on and off, one can increase the observed OCT contrast which can be used for in vivo imaging.26 The development of multifunctional nanoparticles in biomedical imaging has become more critical as the need arises for nanoparticles to detect, diagnose, monitor, and treat diseases. These nanoparticles would complement current imaging technologies by providing higher sensitivity and specificity, with the long-term goal of providing patients with earlier and more localized treatment options. Recently, magnetic and optical nanomaterials have been studied actively for this purpose.27–33 In many of these studies, however, organic fluorophores were used as fluorescent labels that easily photo-bleach in live cells.10,29 In the present study, we demonstrate for the first time the multifuntionality of single-walled carbon nanotube/iron oxide nanoparticle complexes as dual magnetic and fluorescent imaging agents. By encapsulation with DNA, the SWNT/iron oxide nanoparticle complexes are individually dispersed in aqueous solution and are more easily introduced into a biological environment. The iron oxide nanoparticle is located specifically at only one end of the SWNT in an asymmetric arrangement. We characterize the optical properties using Raman, absorption, and photoluminescence spectroscopy, while the magnetic properties are investigated with superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID). We show 2-D in vitro images of murine macrophage cells with these nanostructures using magnetic resonance and near infrared mapping.

Experimental

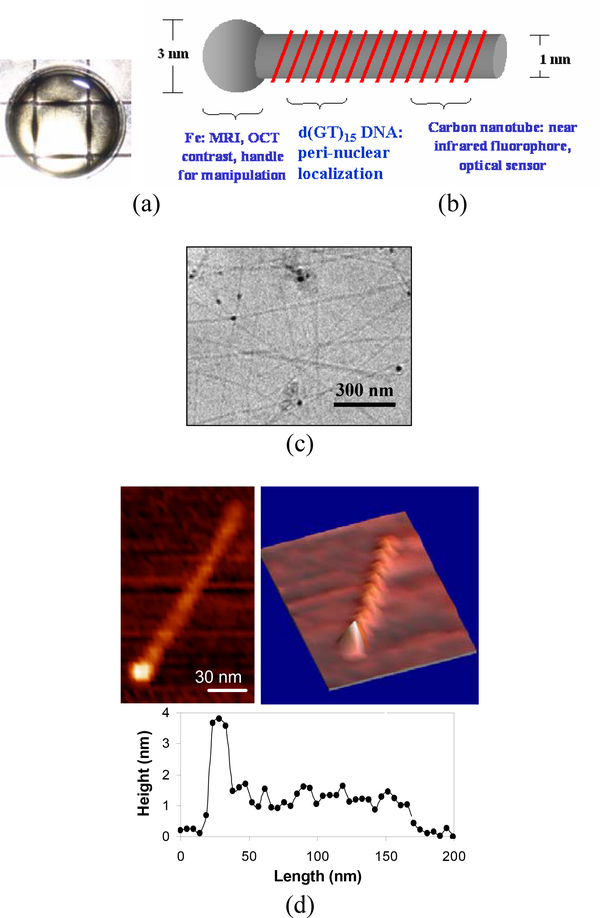

We obtained SWNT from the Rice University Research Reactor (Run 107), which were produced by chemical vapor deposition (CVD) with continuously-flowing CO as the carbon feedstock and a small amount of Fe(CO)5 as the iron-containing catalyst precursor at high pressure (30–50 atm), called the HiPco process.34,35 The process results in iron oxide nanoparticles attached to one end of the nanotube. The SWNT dispersion process using DNA was slightly modified from the method previously described.17,18 Briefly, 1 mg of the as-prepared SWNT was mixed with 1 mg of a 30-mer custom-synthesized DNA sequence of alternating guanine and thymine amino acids, d(GT)15, (Integrated DNA Technologies) in a 1 mL of 0.1 M NaCl solution. The mixture solution was ultrasonicated in a water bath (Branson 1510) for 60 minutes and centrifuged at 16,000 g (Spectrafuge 24D, Labnet International Inc.) for an additional 90 minutes. The supernatant was transferred to a Petri dish placed over an array of ~0.5 T magnets. After two days, the SWNT/iron oxide nanoparticle complexes aggregated along the boundary between adjacent magnets, where the magnetic field gradient was at its highest as shown in Figure 1(a). These aggregates were pipetted out and redispersed by ultrasonication for one minute. This magnetic separation process was repeated five times for further purification. The initial, iron oxide particle-enriched (Fe-enriched), and iron oxide particle-depleted (Fe-depleted) DNA-SWNT samples were prepared with nanotube concentrations of 137, 154, and 159 mg/L, respectively.

Figure 1.

(a) Separation process of single-walled carbon nanotube/iron oxide nanoparticle solution over a ~0.5 T magnetic array. (b) Schematic of the DNA-wrapped nanotube/iron oxide nanoparticle complex. (c) A cryogenic-TEM image showing the heterostructured complexes of the SWNT/iron oxide nanoparticles. (d) 2-D and 3-D AFM images of a complex encapsulated by DNA. The 3-D view shows DNA wrapping of a carbon nanotube. The height profile along the nanotube reveals that the catalyst particle is 3–4 nm in diameter, the nanotube diameter is ~1 nm, and DNA pitch ranges from 12 to 20 nm.

A Shimadzu UV-3101PC absorption spectrometer measured the absorbance of the samples from 190 to 1400 nm. With a 632.8 nm HeNe laser as the excitation source, the NIR fluorescence spectra from SWNT were monitored from 900 to 1400 nm using a liquid N2-cooled InGaAs array detector (OMA V, Princeton Instruments). The Raman signatures and NIR mapping of SWNT were recorded using a Raman spectrometer with a 785 nm excitation from a laser diode (Kaiser Optical Systems Inc.). A cryogenic transmission electron microscope (TEM) and an atomic force microscope (AFM, NanoScope IIIa) were used to visualize the SWNT/iron oxide nanoparticle complexes. The crystal structures of the samples were analyzed with a Rigaku D/Max-b x-ray diffractometer (XRD, Cu Kα radiation: λaverage=1.5418 Å). For XRD sample preparation, the nanotube solution samples containing the same amount of nanotubes (~1 mL) were flocculated using acetone, and the precipitates were deposited onto glass slides. The XRD patterns of the dried samples were recorded for the measurement angle, 2θ from 15 to 70°. A superconducting quantum interference device (1 T magnetic property measurement systems, Quantum Design™) was used to characterize the magnetization properties of the SWNT/iron oxide nanoparticle samples. Approximately 0.65 μg of each of the three prepared nanotube samples was deposited and dried onto individual sheets of parafilm and encapsulated into a gel-cap for SQUID analysis. The measurements were made at 298K using a magnetic field from −1 Tesla to +1 Tesla.

Murine macrophage cells (RAW 264.7) were cultured for MR imaging and NIR mapping. The cultured cells were incubated for approximately seven hours with the nanostructure samples in the cell media, HEPES (4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid)-buffered Dulbecco’s Minimal Essential Media (DMEM, Cellgro 15–018 CV; Mediatech, Herndon, VA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Sigma) and 1% antibiotics.10 After the incubation, these cells were washed with 8 mL phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and re-suspended in the cell media to ensure that any sample materials present would be in the cells and not floating free in the media. The cells were then transferred to 2 mm diameter tubes for MRI and onto glass slides for NIR mapping. MR imaging of the incubated cells was performed at the Biomedical Imaging Center of the Beckman Institute (14.1 T Varian, 600 MHz). Magnetic relaxation timescales were also measured from the samples with different iron contents in Intralipid® (Fresenius Kabi, Uppsala, Sweden), a scattering optical solution commonly used as an optical equivalent for human tissue.

Results and Discussion

High quality SWNT are often grown by disproportionation of carbon-containing molecules (CO or C2H4) using pre-made metal catalyst nanoparticles such as Mo.36,37 The HiPco SWNT used in this study are produced by thermal decomposition in the gas-phase, where iron clusters are generated from Fe(CO)5, and carbon atoms from CO catalytically nucleate to form SWNT and grow in length on the cluster surface.34,35 The nanotube growth is terminated when the iron clusters become too large (relative to the SWNT diameter, e.g., ~1 nm) and overcoated with amorphous carbon or evaporate at a high temperature. The final nanotube product includes 2~5 nm iron particles, with a typical carbon to iron mole % ratio of 97 : 3.35 The individually-dispersed nanotube has one Fe particle on its end as the schematic shows in Figure 1(b). In practice, only a fraction of SWNT are attached to the magnetic particles because either the growth of some nanotubes is terminated by evaporation of the catalysts as described above or the iron nanoparticles may detach during the ultrasonication processing. The cryogenic-TEM image (Figure 1(c)) shows the heterostructured complexes composed of catalyst nanoparticles and single-walled carbon nanotubes. The AFM images in Figure 1(d) confirm complex conjugation with DNA. The 3-dimensional (3-D) view shows DNA wrapping of the carbon nanotube, where it was modeled that the DNA bases are conjugated with carbon nanotube surface through a stacking interaction and the DNA sugar-phosphate backbone on the exterior renders the hybrid complex water-soluble.17 The AFM height profile along the nanotube reveals that the catalyst particle is 3–4 nm in diameter, the nanotube diameter is ~1 nm, and the DNA pitch ranges from 12 to 20 nm.18

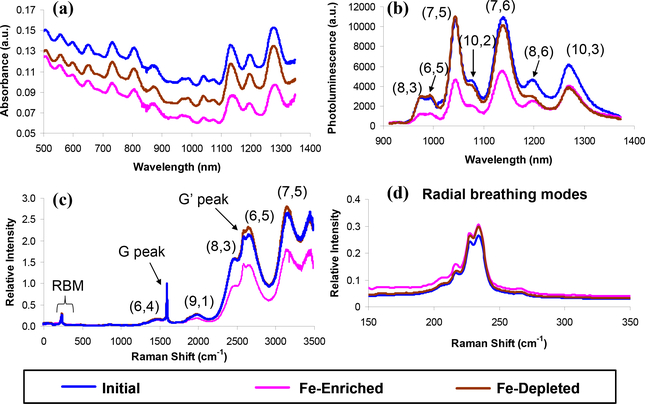

Figure 2 presents UV/vis/NIR absorption, photoluminescence (PL), and Raman spectra of the initial, Fe-enriched, and Fe-depleted DNA-SWNT samples in water. The absorption spectra are offset for comparison, and the PL spectra are corrected for the sample concentrations. The three absorption spectra are not significantly different and clearly show the electronic transitions of metallic and semiconducting nanotube species throughout the visible and near infrared. In the PL spectra (Figure 2(b)), seven distinct features are observed and assigned to seven semiconducting nanotube species as denoted in the figure. These peaks are red-shifted by 15 to 25 nm, compared to sodium dodecyl sulfate-suspended SWNT.2 The discrete optical signatures in both the absorbance and PL spectra indicate that these DNA-wrapped SWNT are individually suspended. Note that the Fe-enriched sample has approximately half the intensity of the other two samples below 1200 nm, whereas the Fe-depleted spectrum becomes similar to the Fe-enriched one above 1200 nm. The nanotube species emitting fluorescence from 900 to 1200 nm have smaller diameters than (8,6) and (10,3) nanotubes. This implies that either the Fe-enriched sample contains fewer nanotubes with smaller diameters than the other two samples or more quenching occurs in those tubes. Our previous study demonstrated that probe-tip sonication cuts a greater proportion of SWNT with larger diameter than that of smaller ones.38 In this work we use a bath sonicator that does not cut a significant fraction of nanotubes, so the lower content of small diameter SWNT in the Fe-enriched sample is not due to the severe nanotube cutting during the ultrasonication. Possible scenarios include more detaching of the catalyst particles from small diameter nanotubes and increased PL quenching from the magnetic cluster in smaller diameter SWNT. The relation between the PL and morphology of the complexes needs more rigorous investigation. Nonetheless, the Fe-enriched SWNT have comparable luminescence throughout the near infrared to the initial and Fe-depleted samples.

Figure 2.

(a) Absorption, (b) photoluminescence, (c) Raman spectra, and (d) Radial breathing modes of the initial, Fe-enriched, and Fe-depleted nanotube samples. The absorbance spectra of the three samples are offset for clarity. The PL and Raman spectra are normalized with respect to the nanotube concentrations and G peak, respectively. The overall optical properties of these samples are not significantly different.

Raman signatures in Figure 2(c) include the radial-breathing modes (RBM) from 200 to 300 cm−1, and G and G’ peaks near 1590 and 2590 cm−1, respectively. These Raman spectra are normalized by the G peak (tangential mode of graphene structures) at 1592 cm−1. Five nanotube fluorescence features are also observed as assigned in the figure. As seen in the PL spectra, the (8,3), (6,5), and (7,5) nanotube peaks of the initial and Fe-depleted samples are similar, and higher than those of the Fe-enriched sample. In all three samples, we do not observe a distinct peak near 267 cm−1 in Figure 2(d), indicative of the absence of nanotube aggregates in the solution: nanotube bundles cause the lowering and broadening in the interband transition energies, resulting in the intensities of the Raman shift to change depending on the nanotube species and the excitation energy.39

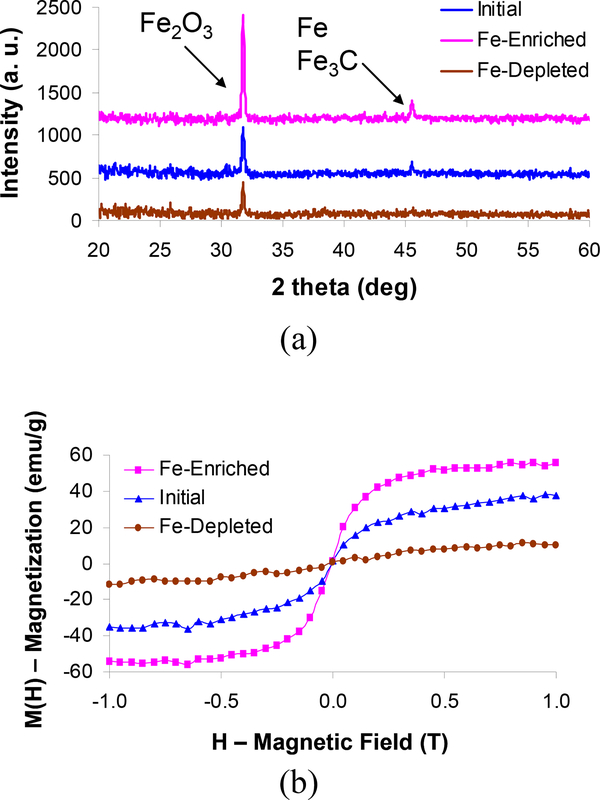

The crystal structures of the initial, Fe-enriched, and Fe-depleted samples are examined by x-ray diffraction in Figure 3(a). The most prominent XRD feature in the Fe-enriched sample is Fe2O3 (JCPDS 89–0599, 39–1346). The other peak is assigned to either the iron in the [1 1 1] plane (JCPDS 88–2324), iron carbide (Fe3C) in the [1 0 3] plane (JCPDS 76–1877), or both. These XRD features were also observed with iron oxide-filled multiwalled carbon nanotubes grown by pyrolysis of ferrocene.40 In the initial sample, the Fe2O3 and Fe/Fe3C peaks are reduced significantly. The iron oxide feature further decreases and the Fe/Fe3C signature is no longer observed in the Fe-depleted sample, indicating that although the Fe-depleted DNA-SWNT sample is not completely free of the magnetic nanoparticles, the content is significantly lower than the Fe-enriched sample. The iron content of the initial sample is between the Fe-enriched and Fe-depleted samples since we separate the SWNT/iron oxide nanoparticle complexes from it. Based on this XRD pattern and our previous x-ray photoelectron spectroscopic (XPS) results of the initial SWNT,41 we estimate that the iron oxide particle contents are 35, 16 and 11% by weight in the Fe-enriched, initial and Fe-depleted samples, respectively.

Figure 3.

(a) X-ray diffraction and (b) SQUID measurements of the initial, Fe-enriched, and Fe-depleted nanotube samples. The XRD reveals that the iron particles are mainly Fe2O3, and the absence of hyteresis in the SQUID indicates the superparamagnetism of the Fe2O3 nanoparticles.

SQUID measurements reveal the magnetic characteristics of the SWNT samples (Figure 3(b)). The Fe-enriched SWNT require the lowest magnetic field (~0.4 T) to reach their magnetization saturation (Ms) which is several times stronger than that of the Fe-depleted sample. The magnetization saturation values of the Fe-enriched, initial and Fe-depleted nanotube samples are 56, 38 and 11 emu/g. Here, the magnetization values were normalized with the total mass of the nanomaterials in each sample to differentiate the magnetic responses of the samples. The results indicate that the major magnetic component of the complexes is the Fe2O3 core rather than the nanotube itself, and the SWNT/iron oxide complexes are effectively separated from the initial stock solution while maintaining their fluorescence properties. Note that the Fe-enriched sample does not exhibit any observable magnetic remnance or hysteresis, suggesting that permanent magnetic dipoles cannot be induced within these complexes. The main reason is that the iron oxide particles are superparamagnetic and 2–5 nm in diameter, about an order of magnitude smaller than those of the iron oxide particles that are known to exhibit ferromagnetic properties. The saturation magnetization of the Fe-enriched sample is in reasonable agreement with that of dextran-coated superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles.21,22

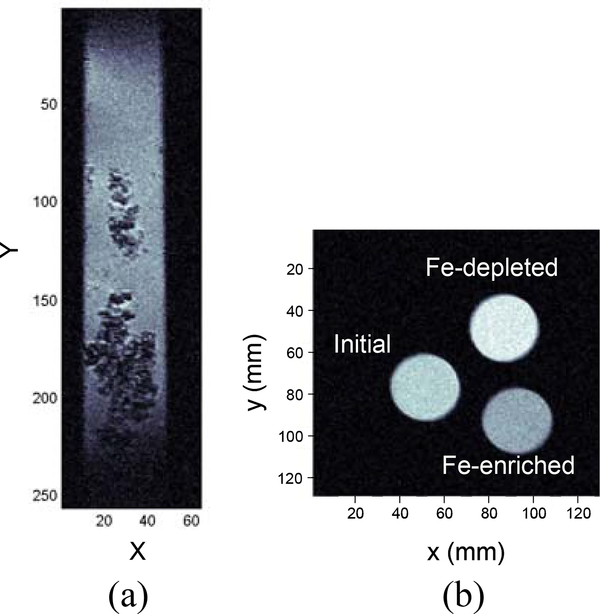

Figure 4(a) shows a MR image of macrophage cells incubated with the Fe-enriched sample. The cell image is generated on a T2-weighted spin-echo multi-slice sequence (SEMS) with a pulse repetition time (TR) of 1.2 s and an echo time (TE) of 10 ms. The image is 7.68 mm × 1.92 mm in size with 256 × 64 pixels, each of which represents 30 μm × 30 μm in plane and 250 μm in depth. Here, the macrophage cells are specifically chosen because they are involved in the immune defense systems of vertebrate animals by engulfing pathogens, and can easily incorporate extraneous particles via phagocytosis. The cells were incubated with the Fe-enriched sample for a nanotube concentration of 10 mg per liter of the cell medium. After a 7 hour incubation, the exact amount of the nanostructures engulfed by the cells is unknown, but the MR image clearly shows the cells as dark spots. Because the iron oxide nanoparticles are T2 agents, the nanoparticles reduce the overall T2 significantly, enhancing the negative image contrast. Control experiments with cells incorporated with the Fe-depleted sample and without any nanomaterials provided no image contrast under the same measurement condition (not shown). We also imaged the cross-sections of capillary tubes containing the three nanotube samples in pure water (Figure 4(b)). This image is obtained based on a T2-weighted SEMS with TR = 1 s and TE = 13 ms. One can readily identify the differences in the image contrast: the dark, intermediate, and light gray areas correspond to the Fe-enriched, initial, and Fe-depleted samples, respectively.

Figure 4.

(a) Vertical MR image of murine macrophage cells with the Fe-enriched SWNT sample. A T2-weighted spin-echo multi-slice sequence (SEMS) is used with a pulse repetition time (TR) of 1.2 s and an echo time (TE) of 10 ms. There are 256 pixels in y-axis and 64 pixels in x-axis. Each pixel has 30 μm × 30 μm in plane and 250 μm in depth. (b) Transverse MR image of the initial, Fe-enriched, and Fe-depleted nanotube samples in water (SEMS, TR = 1 s and TE = 13 ms). A discrete contrast is observed according to the concentration of the iron oxide nanoparticles.

We quantified the differences in the image contrasts created by the samples with different iron content by measuring their magnetic relaxation timescales in Intralipid. Intralipid is chosen here as a viscous matrix in which to disperse the particles, not for its scattering properties as it is usually employed. T2 relaxation time was determined based on the Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill (CPMG) sequence with TR = 4 s and TE = 93 ms, whereas T1 time was obtained based on the inversion recovery sequence (TR = 5 s). With the nanotube concentration of 4 mg/L in the Intralipid, the initial, Fe-enriched, and Fedepleted samples have T1 = 2.52 s and T2 = 261 ms, T1 = 1.91 s and T2 = 164 ms, and T1 = 1.98 s and T2 = 341 ms, respectively. The pure Intralipid with no sample added has T1 = 1.67 s and T2 = 498 ms. T2 decreases with increasing iron oxide particle concentration, and the Fe-enriched sample certainly shows the shortest T2 among the samples. The iron oxide particles predominantly affect T2, although T1 and T2 are not completely independent.20 Better contrast is obtained in T2-weighted images when material with lower T1/T2 ratios as well as greater relaxivities is used. The T1/T2 ratio of the Fe-enriched sample is approximately 12, comparable to the previously reported values of the conventional MRI iron oxide particle agents (T1/T2 = 2 ~ 15).20–22,42 We note that the spin-spin relaxation time (T2) measured here, however, is an order of magnitude longer than Cy5.5 dye-attached iron oxide nanoparticles30 because the iron oxide nanoparticles of the complexes have 2–3 times smaller diameters.

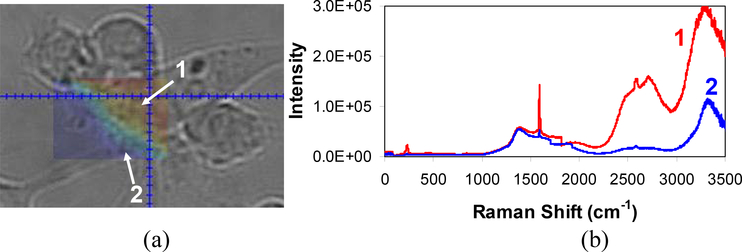

We also used the SWNT component of the complexes as NIR fluorophores to image the macrophage cells. The image of the cells incorporated with the Fe-enriched sample is obtained with an optical microscope as shown in Figure 5(a), where each tick marker represents 2 μm. These cells grow and divide rapidly, forming clusters of cells as observed in the image. Figure 5(a) also includes an overlaid area map constructed by integrating the (8,3) and (6,5) SWNT fluorescence from 958 to 1027 nm, corresponding to 2300 to 3000 cm−1 in the Raman spectra. Two Raman spectra obtained at the locations 1 and 2 in the cell image are shown in Figure 5(b). The cells are plated on a glass slide, so the glass features are seen when compared to the Raman spectra from the sample solution contained in a quartz cuvette (Figure 2(c)). The spectra and map were taken by irradiating 785 nm light (36 mW) for 20 s through a 50x magnification objective lens. The laser spot size was approximately 12 μm in diameter assuming a Gaussian beam. It is important to note that the incubated cells were washed prior to measurement to ensure that no free complexes were present outside the cells. Although we could not resolve the cell structure and the precise location of the complexes due to the large beam size, the NIR map clearly shows the cell boundaries where the bright red areas represent the cell that contains the Fe-enriched DNA-SWNT while the dark blue region indicates the absence of SWNT either outside the cell or in the cell areas that do not contain a large amount of SWNT. A higher resolution optical microscope that is capable of single carbon nanotube spectroscopy would provide information of cell structures in greater detail.

Figure 5.

(a) Image of macrophage cells incorporated with the Fe-enriched SWNT sample through an optical microscope. Each tick marker represents 2 μm. An area map of NIR fluorescence (958 to 1027 nm, corresponding to 2300 to 3000 cm−1 in Raman spectra) from the complexes is overlaid. (b) Raman spectra obtained at two different locations, 1 and 2 in (a). A 785 nm laser diode was used for excitation at 36 mW through a 50x magnification objective lens. The NIR map shows the cell boundaries, where the bright red areas represent the cell that contains the Fe-enriched DNA-SWNT while the dark blue region indicates the absence of SWNT either outside the cell or in the cell areas that do not contain a large amount of SWNT.

The utility of multimodal nanoparticle imaging agents should be evaluated by their functionalities, such as their optical and magnetic properties, and biocompatibilities. First, the nanoparticles scaffolds that utilize semiconductor quantum dots and single-walled carbon nanotubes have several advantages over conventional organic dye-based probes: their fluorescence is distinct, tunable, and photostable. Moreover, biologically transparent NIR fluorescing nanomaterials are favored for in vivo imaging and cell labeling. The complexes can be employed as photodynamic therapy agents because carbon nanotubes have exceptionally large absorption cross-sections in the near infrared.43 Secondly, magnetic nanoparticles that have strong magnetic responses are preferred so that they can not only be used for MRI, but can also be manipulated by an external magnetic field. The saturation magnetization of nanoparticles made of FeCo33 and Co44,45 is 2–3 times greater than that of iron oxide nanoparticles. Recent reports showed that CdSe quantum dots encapsulating a ~10 nm magnetic core had a ~70% lower emission quantum yield46 and a ~90% shorter lifetime45 than the original quantum dots. In contrast, the optical properties of SWNT in this study are not significantly affected by the presence of the iron oxide nanoparticles. We attempted to magnetically modulate the complexes with a 0.02 T solenoid system, but the magnetic force was not sufficient to overcome Brownian motion as the magnetic force exerted on a particle is proportional to the volume of the magnetic component.26 Lastly, the DNA encapsulation renders the complexes water-soluble, biocompatible, and most importantly, optically active in live cells for up to three months.10 The present study suggests that the potential application of these complexes for in vivo imaging depends now upon molecular chemistry to functionalize the complexes to target specific proteins, tumors, and cancer cells.

Conclusions

In this study, we demonstrated for the first time the use of the SWNT/iron oxide nanoparticle complexes as multimodal biomedical imaging agents. The individually-suspended complexes in water were prepared by wrapping the HiPco-produced SWNT with DNA, followed by magnetic separation. We characterized the optical and magnetic properties of the nanotube samples with different iron oxide contents, and imaged macrophage cells containing these nanostructures using magnetic resonance and NIR fluorescence. These results suggest that these complexes could be used to assess tissue or probe individual cells of interest. If the Fe-enriched SWNT are suspended or further functionalized with monoclonal antibodies to target specific receptor sites (e.g., integrin receptors in the development of atherosclerosis and cancer), the complexes could be used as targeted agents to provide molecular-level contrast and biosensing. Finally, the potential exists for these complexes to achieve phototherapy and hyperthermia effects in cells and tissue through NIR laser radiation and the high speed rotation of the nanomaterials upon application of an external magnetic field modulated at a high frequency.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by Arnold and Mabel Beckman Foundation Seed Grant. Support for this work was also provided by the National Science Foundation, with a Career Award to M.S.S., and by the National Institutes of Health (NIBIB 1 R01 EB001777, S.A.B.) and by the NIH Roadmap Initiative (NIBIB 1 R21 EB005321, S.A.B.). J.H.C. expresses his gratitude to the Shen postdoctoral fellowship. We acknowledge the Center for Microanalysis and Materials, and the Magnetic Characterization Facility in the Frederick Seitz Materials Research Laboratory and the Biomedical Imaging Center in the Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology for the use of XRD, SQUID, and MRI facilities. We thank E. Roy, B. Martinez, and L. Ciobanu for providing the macrophage cells, culturing the cells, and performing MR imaging, respectively. We also thank I. Talmon, N. Ryzhenko, R. Kirmse, J. Langowski, and J. Nelson for cryo-TEM, AFM imaging, and AFM analysis.

References

- (1).Avouris P Acc. Chem. Res 2002, 35, 1026–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Bachilo SM; Strano MS; Kittrell C; Hauge RH; Smalley RE; Weisman RB Science 2002, 298, 2361–2366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Barone PW; Baik S; Heller DA; Strano MS Nature Mater 2005, 4, 86–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Hartschuh A; Pedrosa HN; Novotny L; Krauss TD Science 2003, 301, 1354–1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Kono J; Ostojic GN; Zaric S; Strano MS; Shaver J; Hauge RH; Smalley RE Appl. Phys. A 2004, 78, 1093–1098. [Google Scholar]

- (6).O’Connell MJ; Bachilo SM; Huffman CB; Moore VC; Strano MS; Haroz EH; Rialon KL; Boul PJ; Noon WH; Kittrell C; Ma J; Hauge RH; Weisman RB; Smalley RE Science 2002, 297, 593–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Strano MS J. Am. Chem. Soc 2003, 125, 16148–16153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Strano MS; Doorn SK; Haroz EH; Kittrell C; Hauge RH; Smalley RE Nano Lett 2003, 3, 1091–1096. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Doorn SK; Heller DA; Barone PW; Usrey ML; Strano MS Appl. Phys. A 2004, 78, 1147–1155. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Heller DA; Baik S; Eurell TE; Strano MS Adv. Mater 2005, 17, 2793–2799. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Wray S; Cope M; Delpy DT; Wyatt JS; Reynolds EO R. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1988, 933, 184–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Strano MS; Moore VC; Miller MK; Allen MJ; Haroz EH; Kittrell C; Hauge RH; Smalley RE J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol 2003, 3, 81–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Moore VC; Strano MS; Haroz EH; Hauge RH; Smalley RE Nano Lett 2003, 3, 1379–1382. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Chen X; Tam UC; Czlapinski JL; Lee GS; Rabuka D; Zettl A; Bertozzi CR J. Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128, 6292–6293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Karajanagi SS; Yang H; Asuri P; Sellitto E; Dordick JS; Kane RS Langmuir 2006, 22, 1392–1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Richard C; Balavoine F; Schultz P; Ebbesen TW; Mioskowski C Science 2003, 300, 775–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Zheng M; Jagota A; Semike ED; Diner BA; Mclean RS; Lustig SR; Richardson RE; Tassi NG Nature Mater 2003, 2, 338–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Zheng M; Jagota A; Strano MS; Santos AP; Barone PW; Chou SG; Diner BA; Dresselhaous MS; Mclean RS; Onoa GB; Samsonidze GG; Semke ED; Usrey ML; Walls DJ Science 2003, 302, 1545–1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Heller DA; Jeng ES; Yeung T-K; Martinez BM; Moll AE; Gastala JB; Strano MS Science 2006, 311, 508–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Mornet S; Vasseur S; F. G; E. D J. Mater. Chem 2004, 14, 2161–2175. [Google Scholar]

- (21).Jung CW; Jacobs P Magn. Reson. Imaging 1995, 13, 661–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Bulte JWM; Brooks RA; Moskowitz BM; Bryant LH Jr.; Frank JA Magn. Reson. Med 1999, 42, 379–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Wada S; Yue L; Tazawa K; Furuta I; Nagae H; Takemori S; Minaminura T Oral Diseases 2001, 7, 192–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Brasch RC Magn. Reson. Med 1991, 22, 282–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Oldenburg AL; Gunther JR; Boppart SA Opt. Lett 2005, 30, 747–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Oldenburg AL; Toublan FJ; Suslick KS; Wei A; Boppart SA Opt. Exp 2005, 13, 6597–6614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Cai D; Mataraza JM; Qin Z-H; Huang Z; Huang J; Chiles TC; Carnahan D; Kempa K; Ren Z Nature Methods 2005, 2, 449–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Huh Y-M; Jun Y.-w.; Song H-T; Kim S; Choi J.-s.; Lee J-H; Yoon S; Kim K-S; Shin J-S; Suh J-S; Cheon J J. Am. Chem. Soc 2005, 127, 12387–12391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Talanov VS; Regino CAS; Kobayashi H; Bernardo M; Choyke PL; Brechbiel MW Nano Lett 2006, 6, 1459–1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Veiseh O; Sun C; Gunn J; Kohler N; Gabikian P; Lee D; Bhattarai N; Ellenbogen R; Sze R; Hallahan A; Olson J; Zhang M Nano Lett 2005, 5, 1003–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Rieter WJ; Taylor KML; An H; Lin W; Lin WJ Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128, 9024–9025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Zebli B; Susha AS; Sukhorukov GB; Rogach AL; Parak WJ Langmuir 2005, 21, 4262–4265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Seo WS; Lee JH; Sun X; Suzuki Y; Mann D; Liu Z; Terashima M; Yang PC; McConnell MV; Nishimura DG; Dai H Nature Mater 2006, 5, 971–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Nikolaev P; Bronikowski MJ; Bradley RK; Rohmund F; Colbert DT; Smith KA; Smalley RE Chem. Phys. Lett 1999, 313, 91–97. [Google Scholar]

- (35).Bronikowski MJ; Willis PA; Colbert DT; Smith KA; Smalley RE J. Vac. Sci. Technol 2001, 19, 1800–1805. [Google Scholar]

- (36).Hafner JH; Bronikowski MJ; Azamian BR; Nikolaev P; Rinzler AG; Colbert DT; Smith KA; Smalley RE Chem. Phys. Lett 1998, 296, 195–202. [Google Scholar]

- (37).Dai H; Rinzler AG; Nikolaev P; Thess A; Colbert DT; Smalley RE Chem. Phys. Lett 1996, 260, 471–475. [Google Scholar]

- (38).Heller DA; Mayrhofer RM; Baik S; Grinkova YV; Usrey ML; Strano MS J. Am. Chem. Soc 2004, 126, 14567–14573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Heller DA; Barone PW; Swanson JP; Mayrhofer RM; Strano MS J. Phys. Chem. B 2004, 108, 6905–6909. [Google Scholar]

- (40).Schnitzler MC; Oliveira MM; Ugarte D; Zarbin AJ G. Chem. Phys. Lett 2003, 381, 541–548. [Google Scholar]

- (41).Usrey ML; Lippmann ES; Strano MS J. Am. Chem. Soc 2005, 127, 16129–16135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Bulte JWM; Cuyper MD; Frank JA J. Magn. Magn. Mater 1999, 194, 204–209. [Google Scholar]

- (43).Kam NWS; O’Connell MJ; Wisdom JA; Dai H Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 11600–11605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Dumestre F; Chaudret B; Amiens C; Fromen M-C; Casanove M-J; Renaud P; Zurcher P Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2002, 41, 4286–4289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Kim H; Achermann M; Balet LP; Hollingsworth JA; Klimov VI J. Am. Chem. Soc 2005, 127, 544–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Wang D; He J; Rosenzweig N; Rosenzweig Z Nano Lett 2004, 4, 409–413. [Google Scholar]