Abstract

Background

There are over 300 known red blood cell (RBC) antigens and 33 platelet (PLT) antigens that differ between individuals. Sensitization to antigens is a serious complication in prenatal medicine and following blood transfusion, especially for patients requiring multiple transfusions. Although current pre-transfusion compatibility testing largely relies on serologic methods, reagents are not available for many antigens. DNA-based single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) array methods have been applied, but typing for ABO and Rh, the most important blood groups, cannot be done by SNP typing alone. New methods are needed for RBC and PLT antigen determination.

Methods

The MedSeq Project was a randomized clinical trial designed to examine the integration of wide-ranging genomic information into the practice of medicine. Subjects were enrolled by participating physicians during visits for primary care for generally healthy adults and subspecialty care for patients with cardiomyopathy. All participants underwent a standardized family history assessment after which they were block-randomized into either the whole genome sequencing (WGS) arm or the no sequencing arm. The primary endpoint of the overall MedSeq Project was to study the effect of adding WGS to medical care. This study has been completed and is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT01736566. The WGS based RBC and PLT antigen typing presented here is a substudy of the WGS arm with no measured patient outcomes (n=110). A curated database of RBC and PLT antigen molecular changes was created (http://bloodantigens.com), followed by the development of an automated WGS-based antigen typing algorithm (bloodTyper). WGS data from 110 MedSeq participants (30x depth) were used to evaluate bloodTyper against conventional serology and SNP typing for 38 RBC antigens in 12 blood group systems (17 serology and 35 SNP) and 22 PLT antigens (22 SNP). Additional validation was performed using WGS data from 200 INTERVAL participants (15x depth) with serologic comparison (21 RBC antigens).

Findings

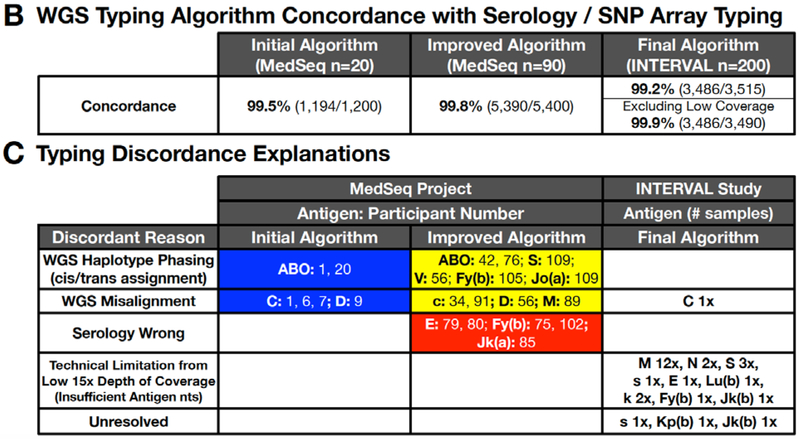

The WGS typing algorithm was iteratively improved to address cis-trans haplotype ambiguities and homologous gene alignments. The initial WGS typing algorithm was 99.5% concordant over the first 20 MedSeq genomes. Addressing the discordances led to the development of an improved algorithm which was 99.8% concordant for the remaining 90 MedSeq genomes. Additional, modifications led to the final algorithm which was 99.2% concordant over 200 INTERVAL genomes (or 99.9% after adjustment for the lower depth of coverage).

Interpretation

By enabling more precise antigen-matching of patients with blood donors, WGS-based antigen typing provides a novel approach to improve transfusion outcomes with the potential to transform the practice of transfusion medicine.

Funding

National Human Genome Research Institute, Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, and NHS Blood and Transplant, National Institute for Health Research, and Wellcome Trust.

Keywords: red blood cell antigen, blood group, human platelet antigen, genomics, whole genome sequencing, next generation sequencing, personalized medicine, transfusion medicine

Introduction

Exposure to non-self red blood cells (RBCs) and platelet (PLT) antigens during transfusion or pregnancy can lead to the development of alloantibodies that can cause mortality and morbidity. Although documented transfusion-related fatalities are rare, approximately fifteen percent of such fatalities reported each year are the result of hemolytic transfusion reactions due to blood group antibodies.1 In addition, sensitization to foreign RBC antigens results in a lifetime of risk for delayed or acute hemolytic transfusion reactions, for fetal anemia and complications in pregnancy.2 For patients requiring chronic transfusion, this sensitization increases the cost and turn-around time for each subsequent transfusion. Similarly, sensitization to foreign PLT antigens can be life-threatening due to ineffective PLT transfusion, and can result in fetal and newborn thrombocytopenia posing a risk for intracranial hemorrhage.2

Antigen typing and matching of the recipient and blood donor for more than the traditional ABO and RhD blood group antigens (termed extended antigen matching) avoids primary sensitization and improves transfusion safety,1 but is not currently standard of practice. Extended antigen typing by antibody-based serologic methods is labor intensive, costly, and reagent antibodies are not available for many clinically significant blood group antigens. Use of DNA array methods that sample single nucleotide (nt) polymorphisms (SNPs) have recently been applied for extended blood group typing, overcoming some limitations of serologic typing methods.3 However, a SNP approach does not target all blood groups, detect all inactive (null) alleles, complex gene rearrangements, or reliably determine alleles encoding ABO and Rh, the most important blood groups.4

By contrast, next generation sequencing (NGS), especially whole genome sequencing (WGS), might overcome these limitations by providing accurate high-resolution typing to inform pre-transfusion antibody screening and enabling routine prophylactic extended blood group matching whenever possible. However, without computerized algorithms capable of robust interpretation of RBC and PLT antigens directly from NGS data, the translation to antigen phenotypes is laborious, time-intensive, and requires deep subject matter expertise.5–12 We recently demonstrated that a subject matter expert could analyze WGS data to determine RBC and PLT antigens comprehensively as a proof of principle.7 We hypothesized that it would be possible to create an automated WGS based antigen typing software whose performance would be concordant with serologic and SNP based typing assays. Here, we report the development and validation of such software including an automated antigen typing algorithm capable of rapid and accurate determination of RBC and PLT antigens from WGS, and consider the potential impact of this technology to improve transfusion medicine practice and safety.

Methods

Study design and participants

Figure 1 illustrates the design of the blood group typing study reported here. Initial participants were those enrolled between December 19, 2012 and January 26, 2017 in the MedSeq Project, a randomized clinical trial designed to examine the integration of wide-ranging genomic information into the practice of medicine.13,14 Enrollment consisted of 10 primary care physicians and 100 of their healthy middle-aged patients to evaluate the use of WGS in general genomic medicine, and 10 cardiologists and 100 of their patients presenting with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy or dilated cardiomyopathy to evaluate the use of WGS in disease-specific genomic medicine. Participants were randomized to either undergo standardized family history assessment plus WGS (n=100) or just standardized family history assessment (n=100). An additional, 10 African American individuals were later recruited as part of an extension phase for WGS. The minimum age for recruitment was 18 years old and the maximum was 90 years. Exclusion criteria consisted of cardiac disease (excluding those enrolled by cardiologists), diabetes mellitus, progressive debilitating illness, pregnancy, spouses/significant others pregnant, untreated clinical anxiety or depression measured by a Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) score > 11 administered at the baseline study visit.

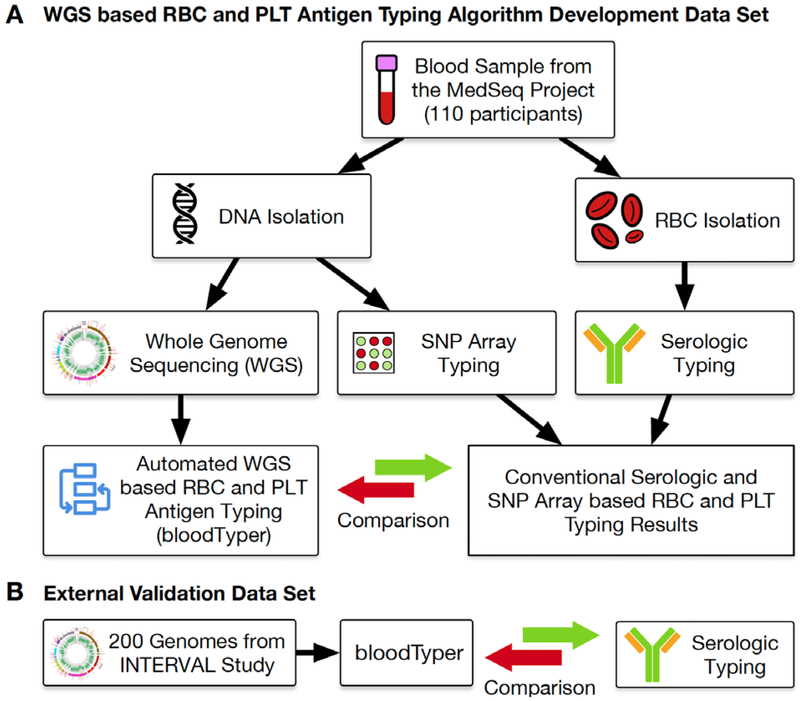

Figure 1.

WGS Study Overview.

(A) DNA and RBC samples were collected from 110 individuals and used for conventional serologic and DNA-based SNP array typing of RBC and PLT antigen. The serologic, SNP array, and WGS based typing results were compared to develop the initial, improved, and final bloodTyper algorithms. (B) The final bloodTyper algorithm was then validated on an additional 200 genomes with blinded comparison to serology.

Detailed in-person informed consent was obtained and included a discussion of risks and additional information to prepare the participant for the vast amount of possible results that could be discovered when undergoing WGS. Participants were block-randomized into either the WGS or control arm by research assistants drawing from sealed envelopes. The sealed envelopes were created by research assistant and genetic counselor staff. In the healthy cohort randomization was sex-matched. In the cardiology cohort, randomization was stratified based on previous genetic testing results. Participants and researchers were not masked and were informed after randomization of the study arm. Participants could be removed from the study if the genome resource center or the safety monitory board felt the study was no longer safe for the participant, or if they were lost to follow-up.

The RBC and PLT analysis presented here was only performed on the 110 MedSeq participants undergoing WGS. The self-identified ethnic backgrounds of the 110 MedSeq participants included 89 (81%) individuals of European ancestry, 13 (12%) African ancestry, 4 (3.6%) Asian, and 4 (3.6%) Hispanic (Appendix page 4). With approval from the Partners HealthCare Human Research Committee (IRB) and informed consent from participants, samples for RBC and genomic DNA isolation were collected. RBCs were typed by conventional serologic typing (see below). DNA was extracted from white blood cells (WBCs) for SNP-based typing and WGS (see below). The MedSeq Project WGS data are available through the database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP) website (Appendix page 4). Additionally, 200 genomes (Appendix page 5) from the INTERVAL study15 with paired RBC serologic phenotyping were used as an external dataset for additional algorithm validation.

Conventional RBC Antigen Serologic Typing, SNP Typing, and RHD Zygosity Testing

For participants in the MedSeq Project, blood samples were collected in EDTA and conventional RBC serologic antigen typing was performed according to standard tube typing methods (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH, United States).2 Commercially available serologic typing reagents were used to type for the ABO, M, N, S, s, D, C, c, E, e, K, k, Fy(a), Fy(b), Jk(a), and Jk(b) from (Bio Rad, Hercules, California, United States for all except; Ortho Clinical Diagnostics, Raritan, United States for Fy(b); and Immucor, Norcross, GA, United States for Jk(a), and Jk(b)). DNA was isolated from WBCs by standard methods and Immucor Precise Type BeadChip HEA (human erythrocyte antigen) array SNP typing (Norcross, GA, United States) was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions to type for M, N, S, s, U, C, c, E, e, V, VS, Lu(a), Lu(b), K, k, Kp(a), Kp(b), Js(a), Js(b), Fy(a), Fy(b), Jk(a), Jk(b), Di(a), Di(b), Sc1, Sc2, Do(a), Do(b), Hy, Jo(a), Co(a), Co(b), LW(a), and LW(b). The Immucor BioArray HPA (human platelet antigen) BeadChip array was used to type for the following PLT antigens: HPA-1a/b, 2a/b, 3a/b, 4a/b, 5a/b, 6a/b, 7a/b, 8a/b, 9a/b, 11a/b, and 15a/b (Norcross, GA, United States).

Conventional RHD zygosity testing was performed using the hybrid box assay according to previously published methods.16 Briefly, allele-specific PCR was carried out using primers designed to amplify a product of 1,507 bp within the hybrid box sequence (Appendix page 5).16 PCR products were visualized by agarose gel electrophoresis with ethidium bromide staining. The RHD zygosity was assigned by: 2x = serologic D+ and no hybrid box present, 1x = serologic D+ and hybrid box present, and 0x = serologic D− and hybrid box present.

MedSeq Project WGS Workflow

Blood samples were collected in PAXgene tubes (PreAnalytiX GmbH, Feldbachstrasse, Switzerland) and genomic DNA was isolated from WBCs by standard methods. For quality control, a genotyping array was performed in parallel to confirm identity and lack of sample inversion during the WGS workflow. This was followed by another blood draw which was also genotyped to serve as an independent verification of identity.

PCR free WGS was performed by the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)-certified, College of America Pathologists (CAP)-accredited Illumina Clinical Services Laboratory (San Diego, CA) using paired-end 100 base pair (bp) reads of DNA fragments with an average length of 300 bp on the Illumina HiSeq platform and sequenced to at least 30x average depth of coverage.17 Sequence read data was aligned to the human reference sequence (GRCh37/hg19) using Burrows-Wheeler Aligner 0.6.1-r104.18 The alignments were further processed to remove duplicates, recalibrate, and realign around indels.

INTERVAL Study WGS Workflow

RBC serologic typing for the INTERVAL study15 participants was extracted from the PULSE database of the National Health Service Blood and Transplant (NHSBT) for ABO, M, N, S, s, D, C, c, E, e, Lu(a), Lu(b), K, k, Kp(a), Kp(b), Fy(a), Fy(b), Jk(a), and Jk(b) antigens. WGS data from 220 INTERVAL participants (20 for initial technical troubleshooting and 200 for algorithm validation) were selected by prioritizing for those with the largest number of serologically typed antigens.

INTERVAL study samples were sequenced to 15x average depth of coverage at the Wellcome Sanger Institute using Illumina HiSeqs. The raw sequencing reads, were converted directly into BAM format using Illumina2BAM. Illumina2BAM was again used to de-multiplex the lanes that had been sequenced so that the tags were isolated from the body of the read, decoded, and could be used to separate out each lane into lanelets containing individual samples from the multiplex library and the PhiX control. Reads corresponding to the PhiX control were mapped using the BWA backtrack algorithm and used as a reference to the Sanger’s spatial filter program to identify reads from other lanelets that contained spatially oriented INDEL artefacts and reads spatially associated with these artefacts were then marked with a BAM flag indicating them as QC fail. The BAM output, after mapping the samples against the human reference genome HS38DH, was fed into samtools fixmates and then sorted into coordinate order. The marking of PCR and optically duplicated reads was then done using the BioBamBam MarkDuplicates tool and after manual QC passing data was deposited with the EGA. Lastly the reads were combined into library CRAMs and duplicates were marked again. To standardize the INTERVAL genomes with those from the MedSeq Project, sequence reads were extracted from the INTERVAL CRAMs and aligned as GRCh37/hg19 BAMs.

RBC and PLT Antigen Typing WGS Workflow

The same general workflow was used to determine RBC and PLT antigens from both the MedSeq and INTERVAL WGS BAMs. Variant calls for 45 RBC and 6 PLT (Appendix page 6) genes were made 300 bases upstream of start codon, exons, and 10 bases into each intron using the Genomic Analysis Tool Kit (GATK) version 2.3–9-gdcdccbb and saved as a variant calling format file (.vcf) showing differences between the WGS data and the reference genome.19 Sequencing coverage was extracted from the alignment file using BEDTools v2.17.0.20 The Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV)21 was used as needed to verify coverage and sequence identity.

Similar to our previous findings,7 there were a few regions of low coverage (RHD [exon 8], C4B, C4A, and CR1), but all MedSeq Project 110 genomes had adequate sequencing coverage to allow for antigen typing from the relevant nt positions at a 4x nt coverage calling cutoff (not including Rh and MNS which were called using modified approaches and cutoffs). For Rh antigen typing, misaligned sequence regions, such as C antigen RHCE exon 2, were specially addressed using the approaches described in the Copy Number Analysis section. For MNS antigen typing, the M antigen which is defined by 3 nt changes located in GYPA exon 2, required a lower 2x calling cutoff. This could be due to the human reference genome GYPA exon 2 encoding for the N antigen defined by three different nts at the same positions as the M antigen. This difference causes the M antigen sequences to inefficiently align to GYPA exon 2, thus requiring a lowering of the calling cutoff to 2x. In addition, there was 10x nt coverage warning cutoff. Both the calling and warning cutoff values can be configured by the user when running bloodTyper.

To evaluate the INTERVAL dataset for technical issues (e.g. file format compatibly, depth of coverage, and any other reasons preventing bloodTyper from working), the first 20 samples were analyzed by bloodTyper, for which it was noted that the lower 15x coverage caused difficulties typing for the M antigen. As noted above, similar issues were found in the 30x average coverage of some MedSeq genomes, leading to the calling cutoff being lowered to 2x for the M antigen. However, the lower 15x average coverage of the INTERVAL genomes, caused even lower M antigen alignment with some genomes as low as 1x and even 0x. In the 200 INTERVAL genomes used for blinded validation; this problem was addressed by setting the M+ antigen cutoff to 1x and including a loss of GYPA exon 2 (M antigen nt location) as a backup M+ typing method similar to the methods used to address C antigen RHCE exon 2 misalignment.

Antigen Allele Database

A comprehensive and curated RBC and PLT antigen allele genotype database was created by subject matter experts who combined the published antigen allele sources.22–27 During the curation process, errors and omissions were detected by manually comparing the published sources and automated cross-correlation checks (e.g. agreement between nucleotide change and position with amino acid identity and position). Our previously published semi-automated nt position conversion process7 was fully automated and used to convert all relevant nucleotide positions from cDNA position numbering (e.g. c.578T in KEL cDNA GenBank sequence M64934) to gDNA coordinates (e.g. chr7:142,655,008T in human reference genome GRCh37/hg19). Our allele database can be viewed at http://bloodantigens.com, where the database will be updated as new blood groups systems and alleles are officially assigned by the relevant international antigen workgroups.

Copy Number Analysis

The Rh blood group system is composed of the highly similar genes RHD and RHCE, which can prove problematic for WGS alignment algorithms. To detect misalignment, copy number was determined for each exon and intron region by a WGS sequence depth of coverage approach using the following calculation: . The average coverage over the RHCE gene was used for background as two copies of RHCE are present in all but very rare samples.

The exon and intron copy number calculations were used to detect structural changes underlying the presence or absence of the D and C antigens. RHD copy number (zygosity) was determine using , with RHD zygosity assigned using the following ranges: homozygous (copy number 1.6–2.5), hemizygous (copy number 0.6–1.5), and null/negative (copy number 0–0.5). The C antigen was determined by misalignment of RHCE exon 2 (loss of sequence reads aligned to RHCE), using with evaluation of two different C antigen regions: (1) RHCE exon 2 only and (2) RHCE exon 2 and surrounding introns that are part of the gene conversion. The C antigen was assigned using the following ranges: C+c– (copy number <0.5), C+c+ (copy number 0.5–1.4), and C–c+ (copy number >=1.5).

RHD and RHCE required special considerations when being used in copy number calculations given: (1) the small 79 bp RHD exon 8 does not align correctly because the reference genome contains RHD*DAU0 allele change chr1:25,643,553C>T; (2) RHCE exon 2 sequences misalign to RHD exon 2 when the RHCE*C allele is present, since RHCE*C exon 2 is identical to RHD exon 2; (3) RHD and RHCE exon 1 show interchangeable alignment when the RHCE*c allele is present, since the human reference is RHCE*c and RHCE*c exon 1 is identical to RHD exon 1. To address this RHD exons 1, 2, and 8 and RHCE exons 1 and 2 were excluded from determination of the average background coverage used to normalize the copy number calculations. This allowed accurate detection of RHCE*C exon 2 even when misaligned to RHD.

WGS Typing Algorithm Development

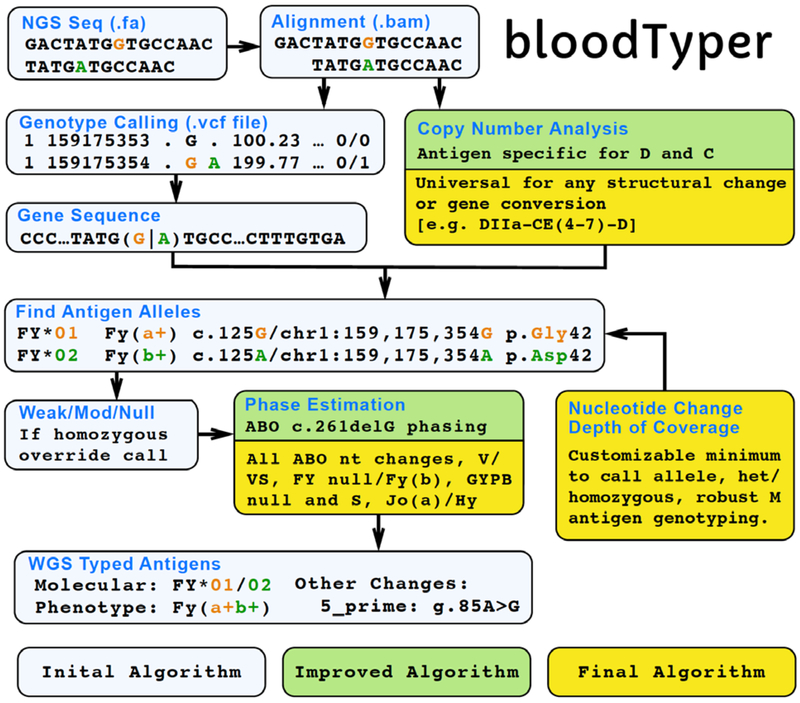

The WGS typing algorithm software (bloodTyper) was designed and implemented through custom developed typing software that was iteratively improved during this study. A total of 110 MedSeq participants were evaluated for RBC and PLT antigens. WGS data from the first 20 participants was typed using an initial algorithm as a learning set to evaluate and improve the performance of the algorithm. The improved algorithm was then used on the remaining 90 MedSeq participants, in which the WGS based antigen typing and the conventional serologic and SNP based DNA typing methods were conducted in a blinded manner on specimens from the same individuals and then compared. Discordant typing results using the improved algorithm were investigated and an updated final algorithm was created which used a combination of gene sequence, sequence coverage, copy number analysis, and misalignment detection to select the correct antigen alleles, which were then integrated to determine the antigen phenotype (Figure 2). The final algorithm was then run blinded on an additional 200 genomes from the INTERVAL study.

Figure 2.

bloodTyper WGS Typing Algorithm.

The bloodTyper WGS typing algorithm was iteratively developed in several stages. The initial algorithm was created based on our previous experience of manually typing from the WGS data of one individual. The initial algorithm was run on the first 20 participants and compared to conventional serology and SNP testing to create an improved algorithm, which was run further on 90 participants in a blinded manner. The comparison of the 90 participants to serology and SNP testing then allowed for the development of a final algorithm, which used a combination of gene sequence, sequence coverage, copy number analysis, and misalignment detection to select the correct antigen alleles, which were then integrated to determine the antigen phenotype. The final algorithm was run on 200 additional genomes and the results blindly compared to serology.

Software and Data Availability

The MedSeq Project genomes are available through dbGaP under study accession phs000958. Complete typing results on all 110 MedSeq participants can be found at http://bloodantigens.com/data. The curated RBC and PLT antigen allele database created for this study is freely available at http://bloodantigens.com. The final algorithm for WGS typing (bloodTyper v3.4) can be downloaded at https://bitbucket.org/lucare/bloodTyper, which includes detailed instructions on how others can reproduce the typing results for the 110 MedSeq Project participants presented here. Use of bloodTyper on other datasets will require that users agree to usage terms with Brigham and Women’s Hospital, which can be initiated by filling out the access request form at http://bloodantigens.com/bloodTyper.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes for the overall MedSeq Project were health care use, anxiety, depression, perceived health, health behaviors, molecular and clinical diagnoses, appropriateness of clinical management, and health care costs, and these have been reported elsewhere.13,14,28–31 However, for the RBC and PLT antigen typing part of MedSeq reported here there were no measured patient outcomes.

Statistical Analysis

The MedSeq Project was designed as a pilot randomized clinical trial of WGS disclosure and exploratory statistics were used for comparison of outcomes between the group underdoing WGS vs the control group.28,29,31 For the RBC and PLT sub-study results presented here only the WGS group was evaluated without any intended comparison to the control group. In this analysis, the WGS based RBC and PLT antigen typing was compared to conventional serologic and SNP testing on the same participant. Excel was used to calculate performance statistics for the RBC and PLT typing methods comparison including: sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value and accuracy. The MedSeq Project is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT01736566.

Role of the Funding Sources

The sponsors of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author (WJL) had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

Design Process

Between December 19, 2012 and January 26, 2017, samples for RBC and DNA isolation were collected from 110 MedSeq Project participants (Appendix page 4) undergoing WGS (Figure 1A) with 30x average depth of coverage to develop a WGS based RBC and PLT typing algorithm (Figure 2). The RBC and PLT types determined by the WGS typing algorithm (Appendix pages 8 and 12) were compared to RBC antigens determined by serology (Appendix page 15) and RBC and PLT antigens determined by SNP array (Appendix pages 18 and 21). Although all antigens with a known molecular basis were evaluated by the WGS typing algorithm, it was only possible to evaluate the performance of the antigens typed by confirmatory methods based on commonly available serologic reagents and the antigens covered by the SNP arrays used.

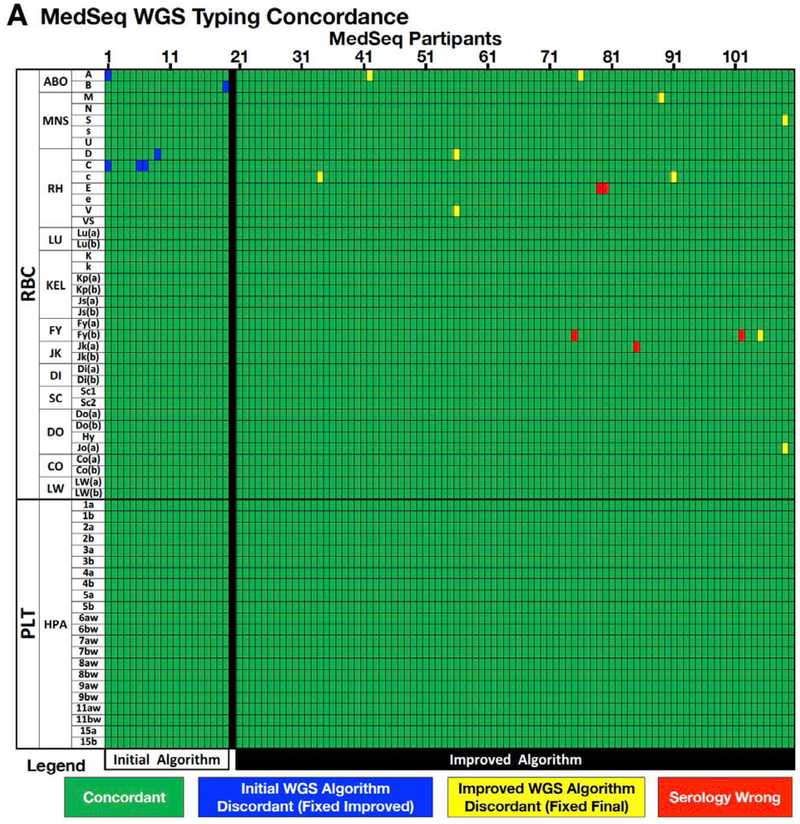

The first 20 of the 110 MedSeq participant samples were used to find errors in the antigen allele genotype database and to design an initial algorithm to translate WGS sequence to the corresponding RBC and PLT antigen types. WGS-based interpretations for these 20 participant samples were then compared to conventional serology or SNP based DNA typing for 38 RBC and 22 PLT antigens (encoded by 17 RBC and 6 PLT genes). The initial algorithm was discordant for two ABO, three C antigens, and one D antigen (Figure 3), for a concordance of 99.5% (1,194 correct calls out of 1,200 individual antigen typings from 20 participants, detailed performance statistics for each antigen can be found in Appendix page 24).

Figure 3.

WGS Antigen Typing Validation.

Results of automated bloodTyper WGS based RBC and PLT antigen typing compared to conventional serologic and DNA-based SNP typing. (A) Concordance for 110 MedSeq samples for 59 (37 RBC and 22 PLT) antigens. (B) Concordance of WGS based antigen typing relative to conventional serologic and SNP typing for the initial, improved, and final WGS antigen typing algorithms. (C) Discrepancies between the antigen typing methods are shown by blood group antigen, sample number, and cause.

Analysis of the cause for each discordant call was used to make changes to the algorithm, and the remaining 90 of 110 MedSeq participant samples were then typed by this improved WGS-based typing algorithm (Figure 2), serologic typing, and SNP typing independently and blinded to the information generated by the other techniques (38 RBC and 22 PLT antigens). The improved algorithm was 99.8% concordant (5,390 correct calls out of 5,400 individual antigen typings from 90 participants, Appendix page 26), with 10 discordant WGS based RBC antigen typings and no discordant PLT antigens (Figure 3). Discordances included six cis-trans haplotype ambiguities and four misalignments in homologous genes (Figure 3), and are discussed for ABO and Rh systems below. There were five additional discordant results that were due to incorrect serologic RBC typing and that were confirmed when serologic testing was repeated. A detailed summary of the causes for discordance and improvements to the final WGS typing algorithm are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

MedSeq Project Discordances and WGS Algorithm Fixes.

| Concordant / Initial (n= 20) Discordant (Improved Fixed) / Improved (n=90 Discordant (Final Fixed) / Serologic typing Error | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant | Antigen | Serology | SNP Array | Initial WGS |

Improved WGS |

Final WGS | Discordance | Algorithm Modification |

| 1 | ABO | B | AB | B | B | Initial Algorithm did not integrate/phase heterozygous A, B, and O nt changes. | Added population allele haplotype frequencies to estimate phase of O c.261delG as in cis to A nt changes. | |

| 1, 6 | C | + | + | − | + | + | Misalignment of WGS RHCE exon 2 sequences onto RHD exon 2. | Added RHCE exon 2 sequence read depth of coverage copy number analysis to detect C antigen. |

| 7 | C | − | − | + | + | − | C antigen misalignment not detected since it was slightly less than the cutoff set after Participant #6. | Copy number analysis specificity and sensitivity for C antigen to include the surrounding intron regions. |

| 9 | D | + | No call |

+ | + | Initial algorithm copy number cutoff to detect presence of RHD too high to call this hemizygous participant (1 copy of RHD gene). | Modified copy number analysis calls for D+ in RHD hemizygous participants. | |

| 20 | ABO | O | B | O | O | Algorithm did not correctly integrate/phase homozygous O c.261delG with heterozygous A and B nt changes. | Modified to call O based on the presence of homozygous c.261delG, regardless of other nt changes | |

| 34, 91 | c | −* | − | + | − | One errant sequence causing incorrect c antigen c.307C genotype. *Serology not performed for the c antigen for participant #34. | Modified with customizable minimum nt coverage cutoff for calling an allele. | |

| 42, 76 | ABO | O | A | O | Inability to integrate/phase two different O alleles (O*01.01 / O*02.01). | Modified to estimate the phase of heterozygous O alleles with different causative nt changes as in trans. | ||

| 56 | D | D+ | No call | D+ DIIIa-CE(4-7)-D* |

Copy number analysis indicated heterozygous wild type RHD along with RHD with exon 4-7 misalignment plus c.186T, c.410T, c.455C changes. Algorithm unable to integrate/phase results | Modified to integrate Rh misalignments into the corresponding homozygous, heterozygous, and hemizygous gene conversions. Sample is heterozygous D+/DIIIa-CE(4-7)-D. (*confirmed by AS-PCR) | ||

| 56 | V | − | + | − | Inability to integrate/phase heterozygous c.733C/G and c.1006G/T. | Modified based on population allele haplotype frequencies to phase c.733G and c.1006T changes in cis to correctly call V– (c.1006T destroys expression of V). | ||

| 75 | Fy(b) | + | − | − | − | Repeat serologic testing on a follow-up sample agreed with WGS algorithm. | Initial serologic typing error. | |

| 79 | E | + | − | − | − | SNP array testing agreed with WGS. Serology done at the same time as #80, likely E results inverted between samples. | Initial serologic typing error. | |

| 80 | E | − | + | + | + | SNP array testing agreed with WGS. Serology done at the same time as #79, likely E results inverted between samples. | Initial serologic typing error. | |

| 85 | Jk(a) | − | + | + | + | Repeat serologic testing on a follow-up sample agreed with WGS algorithm. | Initial serologic typing error. | |

| 89 | M | + | + | − | + | GYPA exon 2 sequences misaligned to GYPE exon 2. M antigen changes did not reach call level. Not a problem in all samples. Some correctly aligned to genotype M. | Algorithm modified to specifically genotype M antigen nt using 2x coverage cutoff outside of normal GATK genotyping step. | |

| 102 | Fy(b) | − | + | + | + | Repeat serologic testing on a frozen aliquot agreed with WGS algorithm. | Initial serologic typing error. | |

| 105 | Fy(b) | − | − | + | − | Failure to integrate/phase heterozygous c.–67c null with Fy(b) nt change. | Algorithm modified based on population allele haplotype frequencies to phase c.–67c in cis with Fy(b) nt change and in trans with Fy(a) nt change. | |

| 109 | S | − | + | − | Failure to integrate/phase heterozygous null GYPB*03N.04 allele nt changes with heterozygous S and s nt changes. | Modified algorithm based on population allele haplotype frequencies to phase GYPB*03N.04 in cis with the S antigen nt changes and in trans with the s antigen nt changes. | ||

| 109 | Jo(a) | − | + − |

− | Failure to integrate/phase heterozygous Jo(a+)/Jo(a−) c.350C/T and Hy+/Hy− c.323 G/T nt changes. | Modified algorithm based on population allele haplotype frequencies to phase Hy and Jo(a) nt changes. Here Hy− cis with Jo(a−) and Jo(a+) cis to Hy−. Since, Hy− weakens the Jo(a+) expression that gives an integrated phenotype of Jo(a−). | ||

The final WGS typing algorithm (Figure 2) then underwent blinded validation by performing WGS based RBC typing (Appendix page 28) on an additional 200 genomes (Appendix page 5) with 15x average depth of coverage from the INTERVAL study compared with serologic RBC antigen phenotypes (Figure 1B, Appendix page 34) for 21 RBC antigens encoded by 14 genes with a 99.2% concordance (3,486 correct calls out of 3,515 individual antigen typings from 200 participants, Appendix page 40). Analysis of the discordances revealed that most were attributable to technical limitations of the lower 15x average depth of coverage for INTERVAL as opposed to the higher 30x average depth of coverage for MedSeq (e.g. the correct antigen nts were detected, but were present below the 4x nt cutoff that was established during the MedSeq round of testing). When adjusted for 15x depth of coverage issues, there was a 99.9% concordance (3,486 correct calls out of 3,490 individual antigen typings from 200 participants, Appendix page 41) for the INTERVAL WGS typing with serologic phenotypes (see Appendix page 42 for a detailed summary of discordances and causes).

Summarized performance statistics of the initial, improved, and final bloodTyper WGS typing algorithms can be found in Appendix page 44.

ABO Blood Group Considerations

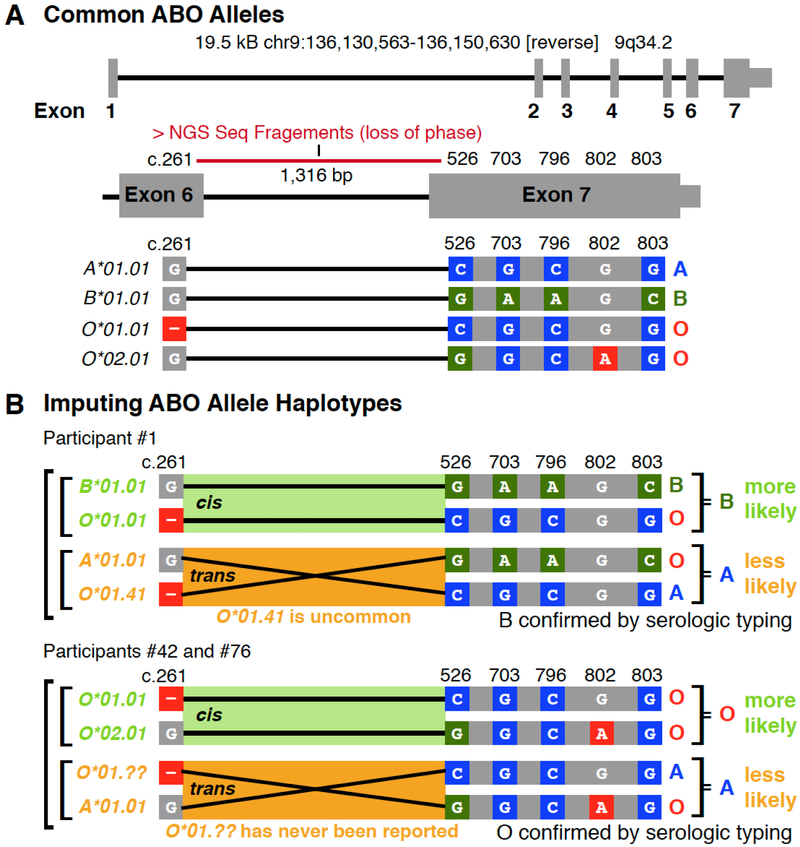

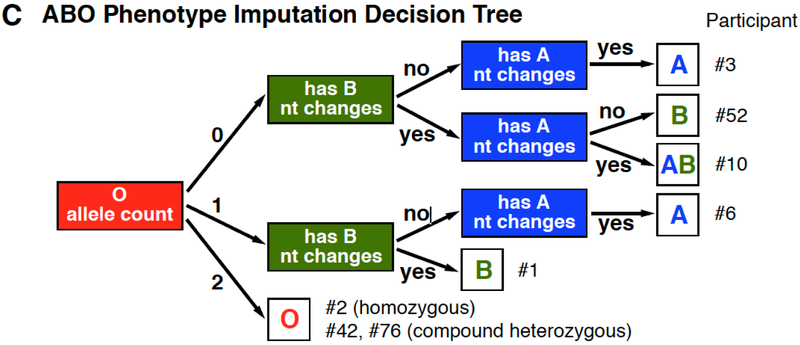

The major changes responsible for ABO transferase specificity and activity are in exons 6 and 7 of the ABO gene.22 Although the exon 7 changes span only 277 bp, the exon 6 and 7 changes are separated by a 1,316 bp intron.22 The average WGS sequence fragment size is 300 bp and therefore determination of the haplotype phase, i.e. the cis or trans relationship of the nucleotide changes between exon 6 and 7 could not be directly determined (Figure 4A). However, the haplotype phase of the nucleotide changes could be imputed/inferred based on known allele frequencies (Figure 4B), which was added to the final algorithm using the decision tree shown in Figure 4C. Imputation involved the type O nt changes c.261delG and c.802A which were phased trans to each other, but cis to exon 7 type A nt changes, an approach which should be highly accurate across most ethnicities. Across the 200 INTERVAL study genomes, the final algorithm was 100% concordant with serology at typing ABO.

Figure 4.

Examples of ABO Typing Algorithm Considerations.

(A) ABO exons 6 and 7 contain the nt positions largely responsible for the activity and specificity of the transferase. (B) Allele haplotypes can be inferred by using know population frequencies to impute the phase between the exon 6 O*01.01 allele deletion (c.261) and the exon 7 changes characteristic of A versus B transferase enzymes (c.526, c.703, c.796, c.803) and the O.02.01 allele nt change (c.802). (C) Decision tree for imputing the ABO phenotype using known haplotype frequencies. The decision tree first evaluates for the number of distinct O nt alleles (e.g. c.261delG or c.802A), followed by an evaluation of c.526, c.703, c.796 and c.803 for the presence of B and then A allele nt changes. Representative participants are listed for each decision output.

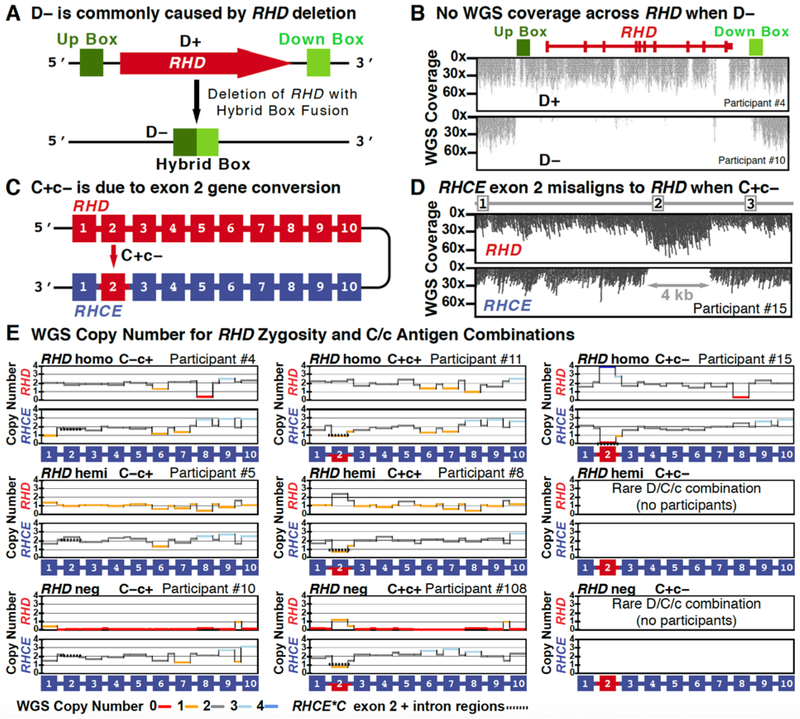

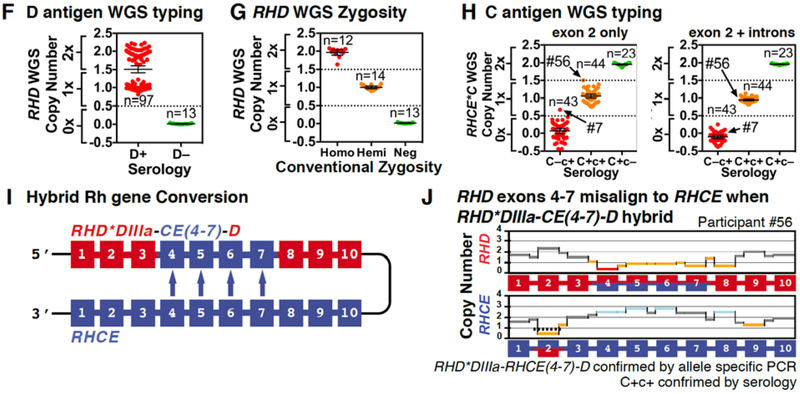

Rh Blood Group Considerations

The Rh system is encoded by two homologous genes, RHD and RHCE, and exon conversion between them results in hybrid alleles. The absence of the D antigen (D−) is most commonly caused by a deletion of the RHD gene (Figure 5A), which is reflected by an absence of WGS sequence reads across the RHD gene region (Figure 5B). The very common C antigen is encoded by a hybrid allele, in which the RHCE exon 2 sequence is replaced by RHD exon 2 (Figure 5C). As such, WGS derived RHCE C antigen exon 2 sequences misalign to RHD exon 2, reflected by an increase in aligned RHD exon 2 sequences and absence of RHCE exon 2 (Figure 5D). Copy number analysis was used to type for the D and C antigens and various allele combinations (Figure 5E). The RHD WGS copy number analysis included in the improved algorithm correctly determined the presence or absence of the D antigen in all 110 participants (Figure 5F), including RHD zygosity in a subset of 40 participants with conventional hybrid box PCR zygosity testing (Figure 5G).

Figure 5.

Examples of Rh Typing Algorithm Considerations.

(A-B) The absence of the D antigen (D−) is most commonly caused by a deletion of the RHD gene which results in fusion of the up and downstream Rhesus boxes into a hybrid box. In D− individuals this leads to a loss of WGS sequence reads over the RHD gene region. (C-D) The presence of the C antigen results in misalignment of RHCE exon 2 (loss of sequence reads) to RHD exon 2 (gain of sequence reads). (E) Copy number analysis was used to detect the D and C antigens. Example copy number plots are show for various combinations of D and C antigens homozygous, heterozygous/hemizygous, and negative states. (F) The presence or absence of reads across the RHD gene was used to calculate the D antigen status across all 110 participants. The two D+ groupings likely represent homozygous and hemizygous RHD states. (G) Conventional RHD zygosity testing for a subset of individuals was compared to WGS D copy number. (H) Copy number analysis was used to type the C antigen status in all 110 individuals. Two approaches were compared: (1) exon 2 alone (initial algorithm) and (2) exon 2 plus surrounding introns (improved algorithm). (I-J) The partial D phenotype RHD*DIIIa-RHCE(4-7)-D allele occurs when RHCE exons 4-7 replace the normal RHD exons. Copy number analysis of exon 4-7 identified RHD*DIIIa-RHCE(4-7)-D, whose automated detection was incorporated into the final algorithm. This same individual was C+ as indicated by the copy number changes seen in exon 2.

Two different C antigen copy number analysis approaches were evaluated for inclusion into the improved algorithm: (1) copy number just for the RHCE 0.2 kb exon 2 and (2) copy number for the entire 4 kb rearranged RHCE C antigen region which includes exon 2 plus parts of the surrounding introns. Across the first 20 participants when exon 2 only was considered, the copy number was discordant with serology for MedSeq participant #7, but when exon 2 plus surrounding introns was considered, the copy number was concordant with serology for all 20 participants and was therefore incorporated into the improved algorithm. The performance of these two different approaches on all 110 MedSeq participants can be seen in Figure 5H.

A hybrid RHD gene, in which RHD exons 4–7 are replaced by RHCE exons 4–7, designated RHD*DIIIa-CE(4–7)-D (Figure 5I), is not uncommon in persons of African ancestry and encodes a D− phenotype as well as a clinically significant partial C phenotype. In MedSeq participant #56, the RHD*DIIIa-CE(4–7)-D hybrid is trans to a normal RHD gene. In the WGS alignment, exons 4–7 (and the intervening introns) misaligned to RHCE (Figure 5J). The final algorithm was programed to analyze RHD-RHCE misalignment using copy number analysis to detect the presence of both a RHD*DIIIa-CE(4–7)-D hybrid and the C antigen gene conversion.

Over the 200 INTERVAL study genomes, the final algorithm was 100% concordant with serology at typing the D antigen and 99.5% accurate at typing the C antigen. The one C antigen discordance was likely due to the copy number analysis misinterpreting a 1x loss of exon 2 coverage over RHCE as C+, when this particular loss of coverage was in the context of a larger 1x loss over exons 2–6, likely indicating a D•• Evan+ C– phenotype due to the presence of a heterozygous RHCE-D(2–6)-CE gene conversion (INTERVAL genome EGAN00001288526).

Clinical Interpretation

In the MedSeq Project protocol, under IRB approval and with patient consent, RBC and PLT extended antigen profiles were summarized for each participant and provided to their physician as part of the clinical report designed for that study.14 The participant’s antigen profile indicates which antigens the patient lacks, and therefore offers the patient’s provider insight about risk of alloantibody sensitization to aid pre-transfusion antibody identification and prenatal antibody screening. This information could be integrated into clinical decision support and utilized when and if a patient might ever need a transfusion. Knowledge of the antigen profile could also be used to recruit participants with uncommon or rare antigen combinations as blood donors. This could be particularly important for individuals who lack high prevalence PLT antigens given the risk of antibody sensitization associated with fetal and neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia post-transfusion purpura, and/or idiopathic platelet transfusion refractoriness. Among the MedSeq cohort tested here, lack of the high prevalence PLT antigens HPA-1a in one, HPA-2a in four, and HPA-5a in three individuals was revealed. Similarly, patients who lack high prevalence RBC antigens might be at risk for antibody sensitization associated with hemolytic or delayed RBC destruction, and or hemolytic disease or anemia of the fetus or newborn (HDFN) for females. Among this cohort, two such individuals were identified as Lu(b–) and Jo(a–). Six of 110 individuals were e–, which occurs in 2–3% of Caucasians and is rare <0.1% in other ethnic groups.2 Additional information of relevance for determining risk for alloantibody production for transfusion included nine patients of African ancestry whose RBCs were typed as Fy(b–) due to a GATA mutation. Because Fy(b) was absent on RBCs but present in tissues, it was presumed that these individuals are not at risk of developing anti-Fy(b) antibodies. The cohort also included participants with uncommon antigens including four V+/VS+, one V-/VS+, three Js(a+), and three Kp(a+), and one Di(a+).

Discussion

Blood transfusion is one of the most commonly administered therapies in clinical medicine, with 112.5 million units of blood collected worldwide every year.32 Current pre-transfusion testing includes matching the patient and donor for ABO and RhD using principles that have not materially changed for over 60 years. Matching of donors and recipients for other common RBC antigens (e.g. C, E, K) is practiced in several Western countries, but not routinely in the United States except for some centers who treat patients with sickle cell disease and thalassemia. Exposure to foreign RBC antigens via red cell transfusion has been reported to lead to production of antigen-specific antibodies in approximately 3% of Caucasian recipients and 30–50% of patients of African ancestry receiving chronic transfusion therapy.1 Once patients are sensitized, they are at increased risk of developing additional red cell antibodies,33 and must receive donor units tested and found to be negative for those antigens for every subsequent transfusion life-long to avoid transfusion reactions. Risk for hemolytic reactions increases because the reactivity of most antibodies falls below the level of detection over time.34 Between 5–16 hemolytic transfusion reaction fatalities stemming from antibodies to blood group antigens (non-ABO) are reported to the FDA each year, with the majority due to the inability to detect pre-existing antibodies or the need for emergency transfusion in patients previously sensitized.

The number of alloantibody complications following transfusion (3%−30% i.e. 3.4 million based on 112.5 million units of blood per year worldwide) has been an accepted level of risk in the absence of efficient strategies for mitigation. Antibody-based serologic typing methods are labor intensive and are not easily scaled, and serologic reagents are not available to type for all clinically significant antigens. Current DNA-based SNP typing methods are limited in the number of polymorphisms targeted, do not interrogate structural changes such as gene conversion events, and are not sufficiently comprehensive to determine ABO and RhD definitively.

The automated analytic software algorithms described in this paper may prove to be vital in the implementation of population level RBC and PLT antigen typing, but further characterization will be required. The ability to test for clinically significant antigens in large populations of donors and recipients for which there are no serologic reagents might significantly mitigate transfusion-related morbidity and mortality. As clinical WGS becomes more commonplace, secondary analysis of existing data might allow inexpensive comprehensive blood group typing to be part of donor and patient medical records.

There are several previous reports of targeted NGS-based RBC antigen prediction, for example, RHD in 26 individuals with weak D antigens,5 RHD and RHCE in 54 individuals,11 K/k allelic polymorphism (c.578) using cell-free fetal DNA in three pregnant females,35 targeted partial sequencing of 18 genes that control 15 blood group systems in four individuals,6 and targeted sequencing of 23 antigens in 48 individuals12. However, because these analyses were often either restricted to a few targeted SNPs or required interpretation by a subject matter expert, sometimes with prior knowledge of the conventional antigen typing results, these methods might not offer a scalable solution for widespread clinical implementation.

Our approach is also not the first effort to create an algorithm for RBC and PLT typing from WGS. For instance, Giollo et al. designed an algorithm to predict RBC antigens for ABO and D typed individuals using hidden Markov models36 and RBC antigen allele data from the now retired Blood Group Antigen Gene Mutation Database (BGMUT)23 using individuals sequenced by the Personal Genome Project. When compared to serology, their concordance was 94% for ABO (n=71) and 94% for RhD (n=69), but their hidden Markov approach makes additional improvements difficult since the typing methodology is abstracted in the predictive model without clear means to address specific discordances. Whereas, our algorithmic rules-based approach allows for iterative improvements based upon molecular analyses of discordances. Our improved algorithm on blinded testing had a concordance of 98% for ABO (n=90) and 99% for RhD (n=90) with serology. We were then able to further improve the algorithm, such that on subsequent blinded testing using another dataset the final algorithm had a concordance of 100% with serology for ABO (n=200) and RhD (n=200). Our efforts also included blinded concordance testing of our WGS typing algorithm for an additional 35 RBC antigens and 22 PLT antigens.

The MedSeq Project cohort represents a cross section of a large urban area of patients at a major academic medical center. Two rare antigen negative individuals were found for Lu(b–) and one Jo(a–). In addition, several RBC antigen changes were identified that are commonly found in individuals of African ancestry, but not in those of European ancestry such as V+, VS+, Js(a+), Fy(a–b–), DIIIa-CE(4)-D. Knowledge of these changes, could allow for better blood product selection either as a recipient or as a potential donor.

However, a limitation of the current study was that not every known RBC or PLT antigen could be tested because some antigens are very rare or only common in specific ethnicities. Similarly, it was not possible to test all known hybrid and structural Rh and MNS changes, meaning that the copy number analysis algorithm will likely require future optimizations. ABO subtyping and hybrid ABO genes were also not tested, which will require updates to the phase estimation decision tree and some form of long range experimental phasing. Therefore, full validation of bloodTyper for all known antigenic changes will require the testing of additional samples representing these untested phenotypes.

In summary, we have created a comprehensive antigen allele genotype database and an automated algorithm for WGS-based RBC and PLT antigen typing that – pending further investigations – might allow routine genetic determination of all key blood group antigens at a level of fidelity comparable to current serologic or SNP array approaches. We posit that this is relevant as Automated RBC and PLT antigen typing algorithms may have the potential to transform the way safe blood products are routinely provided to patients.

Supplementary Material

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Blood transfusion is one of the most common therapies administered in hospitals, but sensitization to red blood cell (RBC) and platelet (PLT) antigens can lead to serious complications in prenatal medicine and transfusion. Although there are over 300 known RBC and 33 PLT antigens, testing in most cases only includes matching the patient and donor for the ABO and RhD antigens. As whole genome sequencing (WGS), becomes increasingly used in medical practice, its use could help modern transfusion therapy, avoid sensitizing the patient to foreign RBC and PLT antigens by improving and expanding matching for additional antigens. For this approach to become high-throughput and cost-effective, however, it will require the contribution of computerized algorithms capable of accurately interpreting WGS data into antigen phenotypes.

Added value of this study

We created a curated database of RBC and PLT antigen molecular changes available at (http://bloodantigens.com), and developed an automated WGS antigen typing software, bloodTyper (http://bloodantigens.com/bloodTyper). The performance of bloodTyper was evaluated using WGS data from 310 individuals with one round of unblinded testing (n=20) and two rounds of blinded testing (n=90 and n=200). In the first round of blinded testing, whole genome based antigen typing from 90 individuals with WGS data from the MedSeq Project (30x depth) was highly concordant (99.8%) with conventional antigen typing by serology (17 antigens from 6 blood group systems) and DNA-based single nucleotide polymorphism testing (35 antigens from 11 blood group systems). In the second round of blinded testing, whole genome based antigen typing from 200 individuals with WGS data from the INTERVAL study (15x depth), was also highly concordant (99.2%) with conventional antigen typing by serology (21 antigens from 7 blood group systems).

Implications of all the available evidence

Whole genome based RBC and PLT antigen typing has the potential to be routinely applied in the clinic to determine extended blood group antigen profiles, but further investigation is warranted. Nevertheless, this study suggests that this WGS algorithm could be used as a comprehensive, accurate and presumably, cost-effective approach to improving transfusion typing, and thus, safety.

Acknowledgements

The MedSeq Project was supported by the National Human Genome Research Institute U01-HG006500. WJL was additionally supported by the Brigham and Women’s Hospital Pathology Department Stanley L. Robbins M.D. Memorial Research Fund Award. D.P.S is additionally supported by T32HL007627, and CMW by the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation #2011097 and #2015133. RCG was additionally supported by U19-HD077671, U01-HG008685, R03-HG008809, UG3-OD023156, U01-AG24904, R01-CA154517, P60-AR047782, R01-AG047866, as well as funding from the Broad Institute and Department of Defense. The authors thank the staff and participants of the MedSeq Project. Recruitment into the INTERVAL study was supported by NHS Blood and Transplant, National Institute for Health Research, British Heart Foundation, and the UK Medical Research Council. Sequencing in INTERVAL was supported by the Wellcome Sanger Institute; data analysis was partly supported by the Cambridge Substantive Site of Health Data Research UK.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests

Dr. Lane reports non-financial support from Illumina, outside the submitted work. Dr. Lebo reports grants from NIH/NHGRI, during the conduct of the study. Dr. Danesh reports grants from UK Medical Research Council, grants from British Heart Foundation, grants from UK National Institute Of Health Research, grants from European Commission, during the conduct of the study; personal fees and non-financial support from Merck Sharp and Dohme UK Atherosclerosis, personal fees and non-financial support from Novartis Cardiovascular and Metabolic Advisory Board, grants from British Heart Foundation, grants from European Research Council, grants from Merck, grants from National Institute of Health Research, grants from NHS Blood and Transplant, grants from Novartis, grants from Pfizer, grants from UK Medical Research Council, grants from Wellcome Trust, grants from AstraZeneca, grants from Pfizer Population Research Advisory Panel, outside the submitted work. Dr. Butterworth reports grants from Merck, grants and personal fees from Novartis, grants from Biogen, grants from Pfizer, grants from AstraZeneca, outside the submitted work. Dr. Rehm reports personal fees from Brigham and Women’s Hospital, outside the submitted work. Dr. Green reports personal fees from AIA, Americord, Veritas, and Helix - all outside the submitted work. All other authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Hendrickson JE, Tormey CA, Shaz BH. Red blood cell alloimmunization mitigation strategies. Transfusion Medicine Reviews 2014; 28(3): 137–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fung MK, Eder AF, Spitalnik SL, Westhoff CM, editors. Technical Manual, 19th edition. 19th ed: American Association of Blood Banks (AABB); 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paccapelo C, Truglio F, Antonietta Villa M, Revelli N, Marconi M. HEA BeadChip technology in immunohematology. Immunohematology / American Red Cross 2015; 31(2): 81–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hashmi G, Shariff T, Zhang Y, et al. Determination of 24 minor red blood cell antigens for more than 2000 blood donors by high-throughput DNA analysis. Transfusion 2007; 47(4): 736–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stabentheiner S, Danzer M, Niklas N, et al. Overcoming methodical limits of standard RHD genotyping by next-generation sequencing. Vox Sanguinis 2011; 100(4): 381–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fichou Y, Audrezet MP, Gueguen P, Le Marechal C, Ferec C. Next-generation sequencing is a credible strategy for blood group genotyping. British Journal of Haematology 2014; 167(4): 554–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lane WJ, Westhoff CM, Uy JM, et al. Comprehensive red blood cell and platelet antigen prediction from whole genome sequencing: proof of principle. Transfusion 2016; 56(3): 743–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mattias Möller MJ, Storry Jill R. and Olsson Martin L. Erythrogene: a database for in-depth analysis of the extensive variation in 36 blood group systems in the 1000 Genomes Project. Blood Advances 2016; 1(3): 240–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baronas J, Westhoff CM, Vege S, et al. RHD Zygosity Determination from Whole Genome Sequencing Data. Blood Disorders & Transfusion 2016; 7(5). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lang K, Wagner I, Schone B, et al. ABO allele-level frequency estimation based on population-scale genotyping by next generation sequencing. BMC Genomics 2016; 17: 374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chou ST, Flanagan JM, Vege S, et al. Whole-exome sequencing for RH genotyping and alloimmunization risk in children with sickle cell anemia. Blood Adv 2017; 1(18): 1414–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orzinska A, Guz K, Mikula M, et al. A preliminary evaluation of next-generation sequencing as a screening tool for targeted genotyping of erythrocyte and platelet antigens in blood donors. Blood Transfus 2017: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vassy JL, Lautenbach DM, McLaughlin HM, et al. The MedSeq Project: a randomized trial of integrating whole genome sequencing into clinical medicine. Trials 2014; 15: 85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vassy JL, McLaughlin HM, MacRae CA, et al. A one-page summary report of genome sequencing for the healthy adult. Public Health Genomics 2015; 18(2): 123–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Di Angelantonio E, Thompson SG, Kaptoge S, et al. Efficiency and safety of varying the frequency of whole blood donation (INTERVAL): a randomised trial of 45 000 donors. Lancet 2017; 390(10110): 2360–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chiu RW, Murphy MF, Fidler C, Zee BC, Wainscoat JS, Lo YM. Determination of RhD zygosity: comparison of a double amplification refractory mutation system approach and a multiplex real-time quantitative PCR approach. Clinical Chemistry 2001; 47(4): 667–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bentley DR, Balasubramanian S, Swerdlow HP, et al. Accurate whole human genome sequencing using reversible terminator chemistry. Nature 2008; 456(7218): 53–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 2010; 26(5): 589–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Research 2010; 20(9): 1297–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quinlan AR, Hall IM. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics 2010; 26(6): 841–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thorvaldsdottir H, Robinson JT, Mesirov JP. Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV): high-performance genomics data visualization and exploration. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2013; 14(2): 178–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reid ME, Lomas-Francis C, Olsson ML. The Blood Group Antigen FactsBook. 3 ed: Academic Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patnaik SK, Helmberg W, Blumenfeld OO. BGMUT: NCBI dbRBC database of allelic variations of genes encoding antigens of blood group systems. Nucleic Acids Research 2012; 40(Database issue): D1023–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.International Society of Blood Transfusion (ISBT): Blood Group Allele Terminology. Available at: http://www.isbtweb.org/working-parties/red-cell-immunogenetics-and-blood-group-terminology/. (Accessed: 1st November 2017).

- 25.Robinson J, Halliwell JA, McWilliam H, Lopez R, Marsh SG. IPD--the Immuno Polymorphism Database. Nucleic Acids Research 2013; 41(Database issue): D1234–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Metcalfe P, Watkins NA, Ouwehand WH, et al. Nomenclature of human platelet antigens. Vox Sanguinis 2003; 85(3): 240–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wagner FF RhesusBase. RhesusBase Available at: http://www.rhesusbase.info/. (Accessed: 20th December 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 28.McLaughlin HM, Ceyhan-Birsoy O, Christensen KD, et al. A systematic approach to the reporting of medically relevant findings from whole genome sequencing. BMC Med Genet 2014; 15: 134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vassy JL, Christensen KD, Schonman EF, et al. The Impact of Whole-Genome Sequencing on the Primary Care and Outcomes of Healthy Adult Patients: A Pilot Randomized Trial. Ann Intern Med 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roberts JS, Robinson JO, Diamond PM, et al. Patient understanding of, satisfaction with, and perceived utility of whole-genome sequencing: findings from the MedSeq Project. Genetics in medicine : official journal of the American College of Medical Genetics 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Christensen KD, Vassy JL, Phillips KA, et al. Short-term costs of integrating whole-genome sequencing into primary care and cardiology settings: a pilot randomized trial. Genetics in medicine : official journal of the American College of Medical Genetics 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.World Health Organization. Blood safety and availability. 2017. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs279/en/ (accessed 3/21/2018 2018).

- 33.Schonewille H, van de Watering LM, Brand A. Additional red blood cell alloantibodies after blood transfusions in a nonhematologic alloimmunized patient cohort: is it time to take precautionary measures? Transfusion 2006; 46(4): 630–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tormey CA, Stack G. The persistence and evanescence of blood group alloantibodies in men. Transfusion 2009; 49(3): 505–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rieneck K, Bak M, Jonson L, et al. Next-generation sequencing: proof of concept for antenatal prediction of the fetal Kell blood group phenotype from cell-free fetal DNA in maternal plasma. Transfusion 2013; 53(11 Suppl 2): 2892–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Giollo M, Minervini G, Scalzotto M, Leonardi E, Ferrari C, Tosatto SC. BOOGIE: Predicting Blood Groups from High Throughput Sequencing Data. PLOS ONE 2015; 10(4): e0124579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The MedSeq Project genomes are available through dbGaP under study accession phs000958. Complete typing results on all 110 MedSeq participants can be found at http://bloodantigens.com/data. The curated RBC and PLT antigen allele database created for this study is freely available at http://bloodantigens.com. The final algorithm for WGS typing (bloodTyper v3.4) can be downloaded at https://bitbucket.org/lucare/bloodTyper, which includes detailed instructions on how others can reproduce the typing results for the 110 MedSeq Project participants presented here. Use of bloodTyper on other datasets will require that users agree to usage terms with Brigham and Women’s Hospital, which can be initiated by filling out the access request form at http://bloodantigens.com/bloodTyper.