Introduction

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection causes a huge burden of disease worldwide. With the advent of ever expanding and highly effective compounds that suppress or even eradicate this virus, great strides have been made.

HBV infection is complicated in many regards, not only by the complexities of the virus and hepatocyte interaction, but also by the host immune response. It typically causes chronic inflammation, the precursor to hepatic fibrogenesis1. In the liver, ongoing fibrogenesis ultimately leads to cirrhosis. HBV cirrhosis affects millions of patients worldwide and is responsible for an extremely high burden of disease2.

Treatment of patients with HBV with nucleos(t)ide analogues is well known to lead to rapid suppression of HBV replication with concomitant reduction in inflammation. Further, this suppression of inflammation provides an intrahepatic milieu such that fibrosis reverses, and further, an improvement in liver function and even survival in patients with complications of cirrhosis. In fact, the data in this area are overwhelmingly positive.

Reversibility of fibrosis and cirrhosis

There is now extensive evidence that liver fibrosis regresses, both in experimental models3 and in human liver disease (for the purposes of this discussion, it is assumed that reversion of fibrosis occurs along a continuum ‒ whether linear or not, and that reversion of fibrosis and reversal of fibrosis may be partial or even complete). These data are highly consistent with the idea that liver wounding, as well as that in essentially all parenchymal organs, is a dynamic one that includes both matrix synthesis and deposition and matrix degradation1, 4.

Further, the data also suggest that fibrosis and even cirrhosis regression is characteristic of virtually all forms of liver disease, and occurs in both experimental models3, 5, 6 and in human liver disease7–14 (Figure 1). Currently available data suggest that in order for fibrosis to regress, the underlying disease must be treated-held in check or cured. This is especially true for liver diseases in which inflammation drives the fibrotic response (see below). Consistent with this concept are data in the HBV field in which there is fairly extensive evidence10, 15–18. Active HBV typically drives inflammation and aggressive fibrogenesis, and elimination of this inflammatory response is associated with a reduction in fibrosis. Further, data are also now emerging in patients with HCV19–21. Further, evidence exists in many other liver diseases as well, including delta hepatitis22, hemochromatosis23, 24, removal of alcohol in alcoholic liver disease25, decompression of biliary obstruction in chronic pancreatitis 12, immunosuppressive treatment of autoimmune liver disease14, and schistosomiasis26.

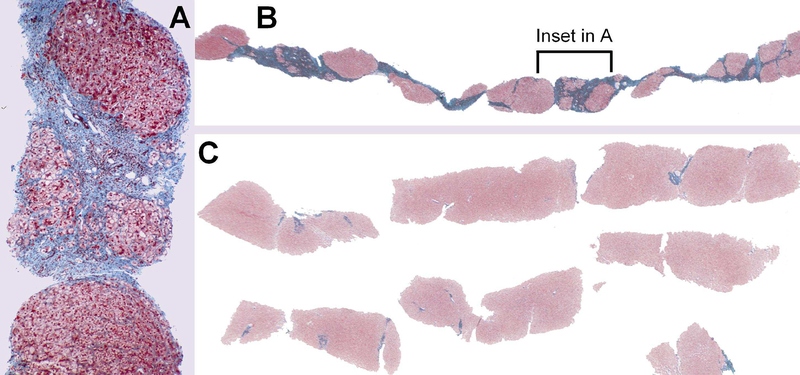

Figure 1.

Histological reversal of fibrosis. An example of reversal of HBV cirrhosis is shown. In (a) and (b) is shown a liver biopsy prior to lamivudine treatment. In (c), after treatment with lamivudine, liver biopsy was repeated, and reveals almost complete dissolution of fibrosis. Data similar to this have been found in patients with autoimmune liver disease, alcoholic hepatitis, hepatitis C, and others. From Wanless IR, Nakashima E, Sherman M. Arch Pathol Lab Med 124:1599–1607, 2000, with permission.

Basic mechanisms

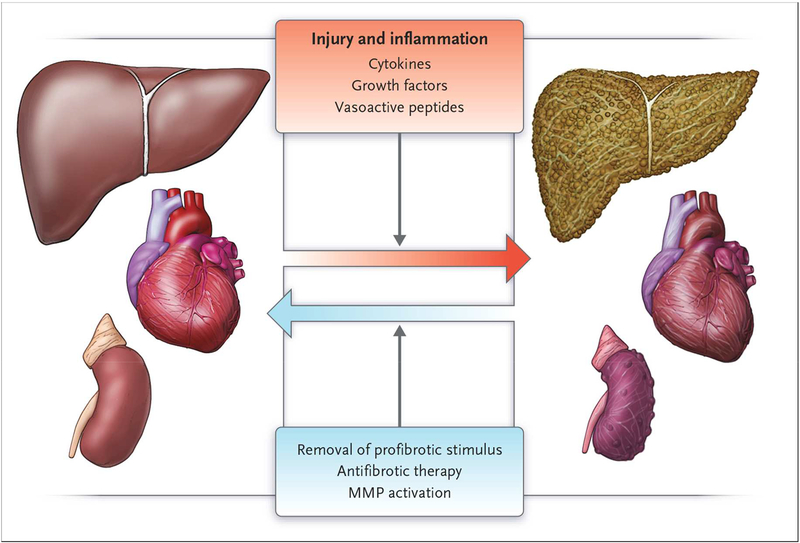

The pathogenesis of all forms of fibrosis is linked to a population of effector cells that produce abnormal amounts of extracellular matrix that is deposited in parenchymal tissue and disrupts organ function1. Further, implicit in this biology is that fibrosis is dynamic, and that there is not only deposition of extracellular matrix, but also that there is also resorption of this matrix. When imbalanced, the result is exaggerated fibrosis, or reversion of fibrosis (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Reversal of organ fibrosis. Fibrosis is remarkably plastic. In many, though not all, instances, tissue fibrosis can be reversed as extracellular matrix proteins are degraded. Often, removal of the inciting stimulus is sufficient, and in a few instances, therapeutic interventions targeting the underlying disease process contribute, as well. From Don C Rockey, P Darwin Bell, and Joseph A Hill. Fibrosis – A Common Pathway to Organ Injury and Failure. N Engl J Med 372:1138–1149, 2015, with permission.

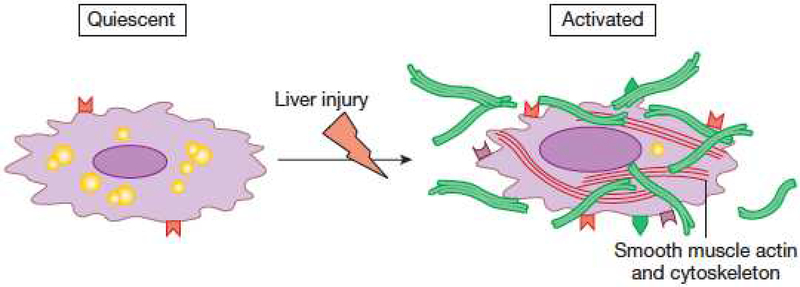

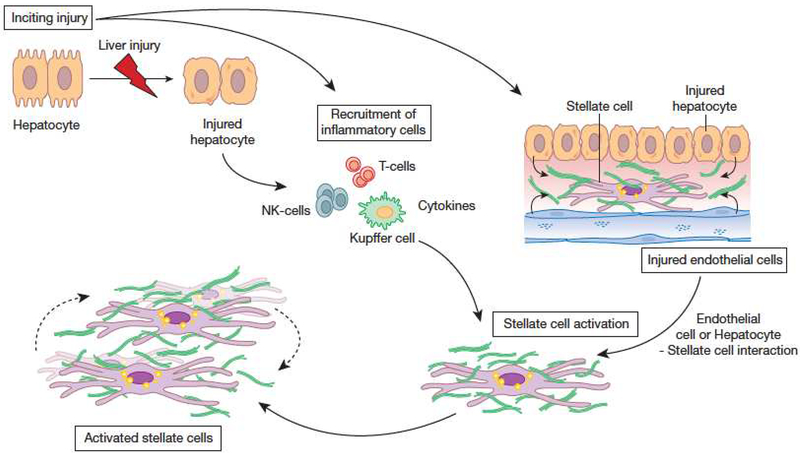

In the liver, the primary effector cell is the hepatic stellate cell (Figure 3), which exhibits a number of key phenotypic characteristics during its activation that in turn drive the fibrogenic response4. In most forms of fibrogenesis, inflammation is a core driver of the fibrotic lesion (Figure 4). This is particularly noteworthy in patients with HBV fibrosis and cirrhosis.

Figure 3.

Stellate cell activation. A key pathogenic feature underlying liver fibrosis and cirrhosis is activation of hepatic stellate cells (note that activation of other effector cells is likely to parallel that of stellate cells). The activation process is complex, both in terms of the events that induce activation and the effects of activation. Multiple and varied stimuli participate in the induction and maintenance of activation, including, but not limited to cytokines, peptides, and the extracellular matrix itself. Phenotypic features of activation include production of extracellular matrix, loss of retinoids, proliferation, of upregulation of smooth muscle proteins, secretion of peptides and cytokines (with autocrine effects on stellate cells and paracrine effects on other cells such as leukocytes and malignant cells – see Figure 4), and upregulation of various cytokine and peptide receptors. Additionally, evidence indicates that stellate cells exhibit several cell fates that are likely to play a critical role in fibrosis regression, highlighted at the bottom of the figure. From Rockey DC. Hepatic Fibrosis. In Yamada’s Textbook of Gastroenterology, Wiley and Sons, Ltd. West Sussex, UK. 2016, with permission.

Figure 4.

The cellular response to wound healing. Most forms of liver injury result in hepatocyte injury, followed by inflammation, leading to activation of HSCs. Inflammatory effectors are multiple and include T cells, NK and NKT cells as well as Kupffer cells. These cells produce growth factors, cytokines, and chemokines that play an important role in stellate cell activation. Additionally, injury leads to disruption of the normal cellular environment, and also to stellate cell activation. Once activated, stellate cells themselves produce a variety of compounds, including growth factors, cytokines, chemokines, and vasoactive peptides. These substances have pleotrophic effects in the local environment, including autocrine effects on stellate cells themselves. ECM synthesis, as well as production of matrix degrading enzymes are major consequences of stellate cell activation. From Rockey DC. Hepatic Fibrosis. In Yamada’s Textbook of Gastroenterology, Wiley and Sons, Ltd. West Sussex, UK. 2016, with permission.

There are undoubtedly multiple mechanisms underlying fibrosis regression. A core concept is that during reversal of fibrosis, there appears to be a specific reduction in stellate cell activation (Figure 5). Extensive data indicate that in cell culture models, stellate cells can be manipulated such that they undergo a transition from an activated to a quiescent state27, 28. This phenotypic reversal also occurs in vivo, although “deactivated” stellate cells appear to exhibit greater responsiveness to recurring fibrogenic stimulation29. Apoptosis of stellate cells also likely accounts for the decrease in number of activated stellate cells typical of resolution of hepatic fibrosis in vivo30. Apoptosis may be inhibited by factors present during injury, or stimulated by other factors as the injury is removed. Additionally, molecules regulating matrix degradation appear closely linked to survival and apoptosis. For example, MMP2 activity correlated with apoptosis, and MMP2 may be stimulated by apoptosis31. Inhibition of MMP2 activity by TIMP-1 also blocks apoptosis in response to a number of apoptotic stimuli32.

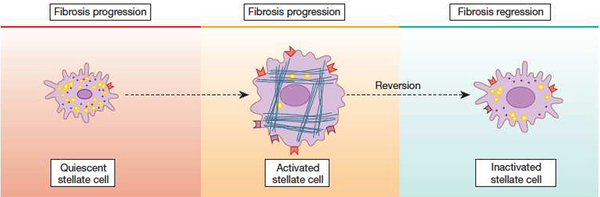

Figure 5.

The cellular mechanism of fibrosis reversion is linked to stellate cell phenotype. Activated hepatic stellate cells are removed from the fibrogenic milieu during fibrosis regression. The mechanism for their removal appears to be via their complete elimination (i.e. via apoptosis) or via reversion from an activated to a quiescent phenotype. From Rockey DC. Hepatic Fibrosis. In Yamada’s Textbook of Gastroenterology, Wiley and Sons, Ltd. West Sussex, UK. 2016, with permission.

Additionally, programmed cell death appears to be linked to autophagy, which appears to stimulate stellate cell activation, and may contribute to the fibrogenic cascade33–36. Cellular senescence has also been proposed to play a role in fibrosis resolution37–39, though the evidence for this in stellate cells is modest.

Clinical considerations

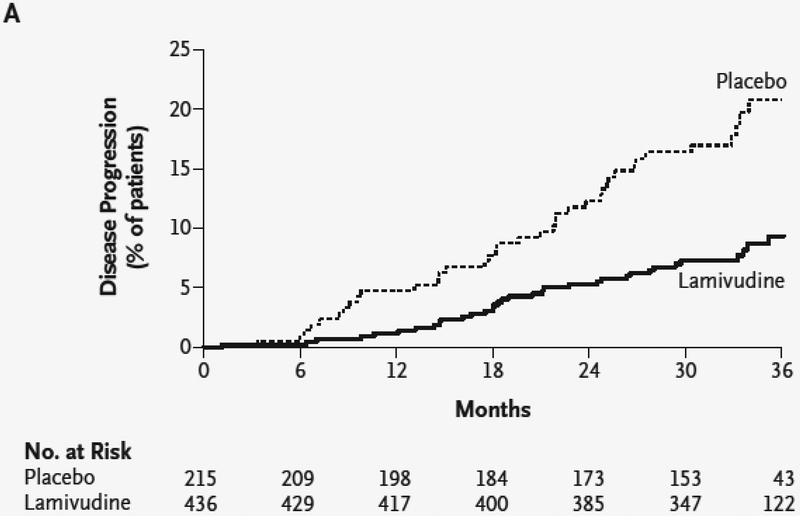

The evidence that effective long-term treatment of patients with HBV and advanced liver fibrosis and even cirrhosis improves clinical outcomes is convincing. Several clinical considerations are noteworthy (Box 1). One of the more convincing studies convincingly established this concept10. In this trial of patients with HBV and advanced fibrosis (Ishak stage 4 or greater) who received lamivudine or placebo, 8% of patients receiving lamivudine and 18% percent of those receiving placebo developed hepatocellular carcinoma, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, bleeding gastroesophageal varices, or had death related to liver disease (P=0.001) (Figure 6)10. Although fibrosis regression was not documented histologically, other data in the field (see below) suggest that the mechanism for the response was almost certainly fibrosis regression. A final point is that for reversion of fibrosis or cirrhosis to be sustained, suppression of HBV replication (with normalization of alanine aminotransferase (ALT)) is essential. A recurrent theme is that the beneficial effects of treatment are not found when there is breakthrough.

Box 1. Critical issues associated with HBV suppression/eradication.

How much fibrosis regression might be expected?

Does it matter which antiviral agent is used?

How long should the antiviral be used?

How should fibrosis regression be measured?

Does fibrosis reversion have an effect on clinical features of cirrhosis (such as QOL, synthetic function, portal hypertension)?

After viral suppression, what is the hepatocellular carcinoma risk?

Figure 6.

Kaplan–Meier estimate of time to disease progression. Patients were randomized to treatment with placebo or lamivudine, and followed for 36 months. Disease progression was defined as the development of hepatocellular carcinoma, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, bleeding gastroesophageal varices, or had death related to liver disease. From Yun-Fan Liaw, Joseph J.Y. Sung, Wan Cheng Chow, et al. Lamivudine for Patients with Chronic Hepatitis B and Advanced Liver Disease. N Engl J Med 351:1521–1531, 2004, with permission.

Fibrosis reversion after HBV suppression

Multiple agents with which to treat HBV are currently available. The evidence suggests that so long as viral replication and the concomitant inflammatory response is suppressed, fibrosis will reverse. Thus, it probably does not matter so much which antiviral agent is used, but rather that it is important that the virus be suppressed or eliminated.

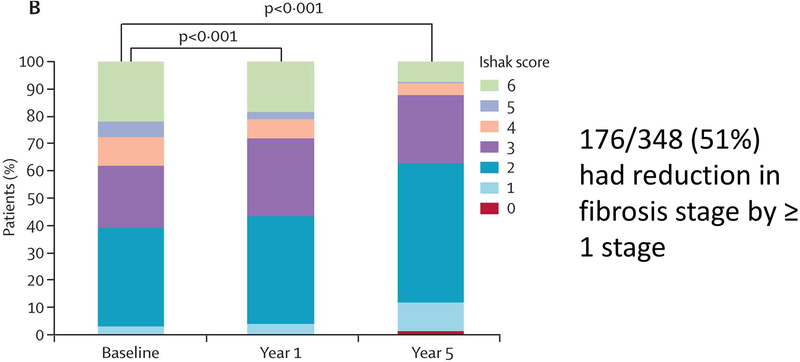

An important question to be addressed is exactly how much fibrosis regression should be expected? In one of the largest histological studies of paired pre- and posttreatment liver biopsies40 treated with an antiviral agent (in this study, tenofovir), 348 patients with HBV and advanced fibrosis had liver histology assessed at baseline and at 5 years (Figure 7). In this group, viral suppression (HBV DNA <400 copies per mL) was documented in 330 (99%) of the 334 patients for whom viral load data were available. In the 96 patients (28%) with histological cirrhosis (defined as Ishak score ≥5) at baseline, 71 (74%) had a reduction in fibrosis at year 5 (and thus did not have histological cirrhosis). The difference between the proportion of patients with cirrhosis regression and without cirrhosis that progressed to cirrhosis (1%) was highly significant (p<0.0001). Further, all but one with regression had a reduction of at least 2 units in the Ishak score at year 5, and more than half (58%, 56 patients) had a decrease of 3 units or more. In the 252 (72%) patients that did not have histological cirrhosis (Ishak score ≤4) at baseline, 12 (5%) had worse fibrosis at year 5; 135 (54%) had no change, and 105 (42%) had improvement. Nine of 12 patients with worsening had an increase in fibrosis score of 1 unit, and three patients (1%) progressed to cirrhosis.

Figure 7.

Histology results over 5-year treatment phase. The Ishak stage (0 to 6) of fibrosis in paired liver biopsy specimens from 348 patients at baseline, at 1 year, and at 5 years of treatment with tenofovir is shown (344 patients had specimens at all 3 time points). From Marcellin P, Gane E, Buti M, et al. Regression of cirrhosis during treatment with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for chronic hepatitis B: a 5-year open-label follow-up study. The Lancet 381: 468–75, 2013, with permission.

In terms of the different HBV antiviral agents, they all appear to have substantial effectiveness in terms of their effects on reversion of advanced fibrosis (40–47, Table 1). It should be emphasized that the general trends in terms of regression are remarkable, and that a majority of patients, but not all patients, should be expected to have fibrosis regression. Again, it is important to emphasize that this occurs in the setting of suppression of viral replication. Interestingly, it is unclear why some patients do not exhibit reversion of fibrosis, although it may be speculated that this has to do with host specific fibrogenic factors.

Table 1.

Effect of antiviral treatment on HBV advanced fibrosis/cirrhosis reversion

| Agent | N (patients) | Fibrosis reversion (%) | Time | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lamividuine | 30 24 47 |

67% 46% 49% |

3 years 3 years 1 year |

41 42 45 |

| Adefovir | 12 15 |

58% 60% |

5 years 5 years |

43 44 |

| Entecavir | 97 13 10 |

57–59% 85% 100% |

1 year 3 years 5 years |

45 47 46 |

| Tenofovir | 96 | 74% | 5 years | 17 |

In terms of the duration of treatment, the data suggest long-term therapy is desirable. In the above study (Figure 7, and40) of tenofovir, this agent appeared to be safe and effective when given for 5 years, and there is no reason to believe that even longer term treatment would not be safe. Further, given the natural history of HBV cirrhosis, it is expected that the longer the durability of viral suppression, the greater the effect on clinical outcomes.

Measurement of fibrosis

Measurement of fibrosis is important for several reasons. First, it helps to stage liver disease, but also to monitor fibrosis after therapy. There is considerable controversy about how to best measure fibrosis. Liver biopsy and histology, long considered to be the gold standard is invasive, and may be subject to sampling error48. Clinical methods (use of physical findings, and routine laboratory tests such as platelets alone) are typically insensitive and not specific. A plethora of blood based test algorithms and serum markers of fibrosis (i.e. TIMP1, MMP2, collagen I, III, IV, hyaluronic acid, and others) have been developed and studied extensively in patients with HCV. Several have also been examined in HBV. The bulk of the data suggest that these tests have a high sensitivity and specificity for detection of far advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis, but are not highly sensitive or specific for less advanced stages of fibrosis49. Additionally, several imaging modalities, in particular vibration control transient elastography (also simply transient elastography) and magnetic resonance elastography are attractive to stage fibrosis because they are non-invasive. Like blood tests and serum marker panels, they are best for advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis, and less sensitive and specific for intermediate degrees of fibrosis49. It is clear that more research will be required in the area of monitoring of fibrosis regression.

Anti-fibrotic therapy

Since the degree of liver fibrosis is highly desirable because it appears to lead to the complications of chronic liver disease, including impaired synthetic function, liver failure, and perhaps hepatocellular cancer. Fibrosis is also tightly linked to portal hypertension. Although attempts have been made previously to specifically treat the “fibrosis” component of liver disease, these approaches have generally been unsuccessful (see1, 4 for review). Thus, fibrosis represents a major unmet need in the field.

As highlighted above, the most effective “anti-fibrotic” therapies are clearly those that treat or remove the underlying stimulus to fibrogenesis. With highly active and effective nucleos(t)ide analogues, this issue is important. Not only would it be expected for an antifibrotic agent to have beneficial effects in this population, but certain mechanistic approaches might be particularly attractive. For example, a compound that affects collagen crosslinking that might break down formed fibrous tissue, such as lysyl oxidase-like-250, is attractive.

Reversion of fibrosis and outcomes with viral suppression

Abundant evidence in the HBV field indicates that treatment of patients with advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis - and with complications of HBV cirrhosis, including with esophageal varices, ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, and coagulopathy - with nucleos(t)ide analogues improves outcomes10, 51–57. The evidence that this is related to fibrosis reversion is correlative, but is supported by data that indicate that treatment of patients with nucleos(t)ide analogues not only reduces fibrosis, but also has effects on portal hypertension. Notwithstanding, it is important to recognize that even though fibrosis may be improved, the pathologic deposition of extracellular matrix and subsequent alteration in sinusoids and in blood flow may not necessarily be reversed. Since outcomes appear to be most closely tied to portal hypertension, this point is critical.

The natural history of HBV cirrhosis suggests that after the development of complications, prognosis is poor, with a 5-year survival of approximately 25%. In contrast, although the long-term mortality in patients with complications of HBV cirrhosis after treatment with an oral HBV antiviral agent is not entirely clear, the 1 year survival for these patients is typically over 80% and may be over 90%51–57. Essentially all of the currently used oral antiviral agents (lamivudine, adefovir, entecavir, telbivudine, or tenofovir) have been shown to lead to improved prognosis in patients with HBV and decompensated cirrhosis.

While the studies examining HBV mediated decompensated cirrhosis have had different designs and have used different antivirals, the data suggest the following: 1) the oral antiviral agents all appear to be safe and effective, 2) clinical improvements in some patients have been such that some patients have been removed from liver transplant wait lists, 3) it has generally be recommended that because of the infrequency of development of resistance, entecavir and tenofovir are the best choices for treatment of patients with HBV and decompensated cirrhosis, 4) all cirrhotic patients with decompensation should be treated, regardless of HBV DNA level as early as possible, 5) oral agents (lamivudine, adefovir, entecavir, telbivudine, or tenofovir) are generally well tolerated without significant side effects. Again, while these specific studies have focused on clinical endpoints and have generally not proven that there is a reversal of fibrosis/cirrhosis, the correlation between a change in fibrosis and outcome appears to be robust.

Further evidence of the benefit of HBV antiviral agents comes from large population studies. Over the time period from 1985 to 2006, which coincided with the introduction of HBV antiviral agents, of 4793 patients with HBV cirrhosis wait listed for liver transplant, compared to, 40,923 with HCV cirrhosis, and 68,211 with neither type of viral disease, the decrease in incidence of waiting list registration was most pronounced for HBV cirrhosis58. Further, the increase in listing for HCC associated with HBV was least dramatic. These data suggested that the widespread use of oral antiviral therapy for HBV contributed to the decreased incidence of decompensated liver disease.

Despite the remarkable results in treating HBV cirrhosis patients with oral agents, there are some patients in whom the disease is too far advanced to expect a benefit. However, the clinical variables associated with a lack of response are currently unknown. Thus, it is this author’s opinion that all patients with cirrhosis should be treated.

The risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) after viral suppression

Cirrhosis appears to be the most important risk factor for development of HCC. As such, reversal of fibrosis and cirrhosis would be expected to reduce the risk of development of HCC. In a large randomized trial of patients with HBV and advanced fibrosis (Ishak stage 4 or greater) who received lamivudine or placebo, 3.9% of patients receiving lamivudine and 7.4% percent of those receiving placebo developed hepatocellular carcinoma, (P=0.047), suggesting that viral suppression and reversal of fibrosis can prevent the development of HCC. Other studies, including meta-analyses have suggested a similar reduction in the risk of development of HCC59–62. Although the risk of development of HCC appears to be low in certain patients with viral clearance (the strongest evidence appears to be in Asian patients), this affect does not appear to be uniform. For example, in a study of entecavir for treatment of HBV including 744 total patients and 164 patients with cirrhosis, during a median follow-up of 167 weeks, 14 patients developed HCC of whom nine (64%) had cirrhosis at baseline. The 5-year cumulative incidence rate of HCC was 2.1% for non-cirrhotic and 10.9% for cirrhotic patients (p<0.001). Further, Caucasian patients appeared to maintain the highest HCC risk63.

Summary and Recommendations

Great strides have been made in the field of HBV related fibrosis and cirrhosis. Currently, the evidence indicates that HBV viral suppression causes regression of advanced fibrosis and even cirrhosis in some patients, and therefore should be attempted in all patients with advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis. The preferred agents in patients with cirrhosis are entecavir and tenofovir, primarily because the risk of breakthrough is low. HBV viral suppression also leads to improved clinical outcomes even in patients with cirrhosis and complications (esophageal varices, ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, and coagulopathy). The risk of subsequent development of hepatocellular carcinoma is reduced after viral suppression, particularly in Asian patients, but less so in Caucasian patients. Thus, patients with HBV cirrhosis should continue to have routine screening for HCC, even after viral suppression.

Key Points.

Robust data indicate that fibrosis regresses in patients with advanced fibrosis and even histological evidence of cirrhosis, after HBV viral suppression.

Overall outcomes are improved in patients with HBV viral suppression, including in those with cirrhosis and complications of cirrhosis.

The risk of subsequent development of hepatocellular carcinoma is reduced after viral suppression.

Despite viral suppression, there appears to be some risk of future development of complications such as portal hypertension and/or hepatocellular carcinoma; the latter most commonly in patients with cirrhosis.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The author has nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Rockey DC, Bell PD, Hill JA. Fibrosis--a common pathway to organ injury and failure. N Engl J Med 2015;372(12):1138–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012;380(9859):2095–2128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iredale JP, Benyon RC, Pickering J, et al. Mechanisms of spontaneous resolution of rat liver fibrosis. Hepatic stellate cell apoptosis and reduced hepatic expression of metalloproteinase inhibitors. J Clin Invest 1998;102(3):538–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rockey DC. Translating an understanding of the pathogenesis of hepatic fibrosis to novel therapies. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association 2013;11(3):224–231 e221–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rockey DC. Antifibrotic therapy in chronic liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005;3(2):95–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rockey DC, Chung JJ. Endothelin antagonism in experimental hepatic fibrosis. Implications for endothelin in the pathogenesis of wound healing. J Clin Invest 1996;98(6):1381–1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ellis EL, Mann DA. Clinical evidence for the regression of liver fibrosis. J Hepatol 2012;56(5):1171–1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crespo-Leiro MG, Robles O, Paniagua MJ, et al. Reversal of cardiac cirrhosis following orthotopic heart transplantation. Am J Transplant 2008;8(6):1336–1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Czaja AJ, Carpenter HA. Decreased fibrosis during corticosteroid therapy of autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol 2004;40(4):646–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liaw YF, Sung JJ, Chow WC, et al. Lamivudine for patients with chronic hepatitis B and advanced liver disease. N Engl J Med 2004;351(15):1521–1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.El-Husseini R, Kaplan MM. Reversal of portal hypertension in a patient with primary biliary cirrhosis: disappearance of esophageal varices and thrombocytopenia. Am J Gastroenterol 2004;99(9):1859–1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hammel P, Couvelard A, O’Toole D, et al. Regression of liver fibrosis after biliary drainage in patients with chronic pancreatitis and stenosis of the common bile duct. N Engl J Med 2001;344(6):418–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wanless IR, Nakashima E, Sherman M. Regression of human cirrhosis. Morphologic features and the genesis of incomplete septal cirrhosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2000;124(11):1599–1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dufour JF, DeLellis R, Kaplan MM. Reversibility of hepatic fibrosis in autoimmune hepatitis. Ann Intern Med 1997;127(11):981–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kweon YO, Goodman ZD, Dienstag JL, et al. Decreasing fibrogenesis: an immunohistochemical study of paired liver biopsies following lamivudine therapy for chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol 2001;35(6):749–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang TT, Liaw YF, Wu SS, et al. Long-term entecavir therapy results in the reversal of fibrosis/cirrhosis and continued histological improvement in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology 2010;52(3):866–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marcellin P, Gane E, Buti M, et al. Regression of cirrhosis during treatment with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for chronic hepatitis B: a 5-year open-label follow-up study. Lancet 2013;381(9865):468–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liaw YF. Reversal of cirrhosis: an achievable goal of hepatitis B antiviral therapy. J Hepatol 2013;59(4):880–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shiratori Y, Imazeki F, Moriyama M, et al. Histologic improvement of fibrosis in patients with hepatitis C who have sustained response to interferon therapy. Ann Intern Med 2000;132(7):517–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poynard T, McHutchison J, Manns M, et al. Impact of pegylated interferon alfa-2b and ribavirin on liver fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology 2002;122(5):1303–1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mallet V, Gilgenkrantz H, Serpaggi J, et al. Brief communication: the relationship of regression of cirrhosis to outcome in chronic hepatitis C. Ann Intern Med 2008;149(6):399–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farci P, Roskams T, Chessa L, et al. Long-term benefit of interferon alpha therapy of chronic hepatitis D: regression of advanced hepatic fibrosis. Gastroenterology 2004;126(7):1740–1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Powell LW, Kerr JF. Reversal of “cirrhosis” in idiopathic haemochromatosis following long-term intensive venesection therapy. Australas Ann Med 1970;19(1):54–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blumberg RS, Chopra S, Ibrahim R, et al. Primary hepatocellular carcinoma in idiopathic hemochromatosis after reversal of cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 1988;95(5):1399–1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sorensen TI, Orholm M, Bentsen KD, et al. Prospective evaluation of alcohol abuse and alcoholic liver injury in men as predictors of development of cirrhosis. Lancet 1984;2(8397):241–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berhe N, Myrvang B, Gundersen SG. Reversibility of schistosomal periportal thickening/fibrosis after praziquantel therapy: a twenty-six month follow-up study in Ethiopia. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene 2008;78(2):228–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sohara N, Znoyko I, Levy MT, et al. Reversal of activation of human myofibroblast-like cells by culture on a basement membrane-like substrate. J Hepatol 2002;37(2):214–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deleve LD, Wang X, Guo Y. Sinusoidal endothelial cells prevent rat stellate cell activation and promote reversion to quiescence. Hepatology 2008;48(3):920–930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Troeger JS, Mederacke I, Gwak GY, et al. Deactivation of hepatic stellate cells during liver fibrosis resolution in mice. Gastroenterology 2012;143(4):1073–1083 e1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iredale JP. Stellate cell behavior during resolution of liver injury. Seminars in Liver Disease 2001;21(3):427–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Preaux AM, D’Ortho MP, Bralet MP, et al. Apoptosis of human hepatic myofibroblasts promotes activation of matrix metalloproteinase-2. Hepatology 2002;36(3):615–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li L, Tao J, Davaille J, et al. 15-deoxy-Delta 12,14-prostaglandin J2 induces apoptosis of human hepatic myofibroblasts. A pathway involving oxidative stress independently of peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptors. J Biol Chem 2001;276(41):38152–38158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thoen LF, Guimaraes EL, Grunsven LA. Autophagy: a new player in hepatic stellate cell activation. Autophagy 2012;8(1):126–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thoen LF, Guimaraes EL, Dolle L, et al. A role for autophagy during hepatic stellate cell activation. J Hepatol 2011;55(6):1353–1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hernndez-Gea V, Friedman SL. Autophagy fuels tissue fibrogenesis. Autophagy 2012;8(5):849–850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hernandez-Gea V, Ghiassi-Nejad Z, Rozenfeld R, et al. Autophagy releases lipid that promotes fibrogenesis by activated hepatic stellate cells in mice and in human tissues. Gastroenterology 2012;142(4):938–946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schnabl B, Purbeck CA, Choi YH, et al. Replicative senescence of activated human hepatic stellate cells is accompanied by a pronounced inflammatory but less fibrogenic phenotype. Hepatology 2003;37(3):653–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krizhanovsky V, Yon M, Dickins RA, et al. Senescence of activated stellate cells limits liver fibrosis. Cell 2008;134(4):657–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kong X, Feng D, Wang H, et al. Interleukin-22 induces hepatic stellate cell senescence and restricts liver fibrosis in mice. Hepatology 2012;56(3):1150–1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marcellin P, Asselah T. Long-term therapy for chronic hepatitis B: hepatitis B virus DNA suppression leading to cirrhosis reversal. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;28(6):912–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dienstag JL, Goldin RD, Heathcote EJ, et al. Histological outcome during long-term lamivudine therapy. Gastroenterology 2003;124(1):105–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rizzetto M, Tassopoulos NC, Goldin RD, et al. Extended lamivudine treatment in patients with HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol 2005;42(2):173–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hadziyannis SJ, Tassopoulos NC, Heathcote EJ, et al. Long-term therapy with adefovir dipivoxil for HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B for up to 5 years. Gastroenterology 2006;131(6):1743–1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marcellin P, Chang TT, Lim SG, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of adefovir dipivoxil for the treatment of hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology 2008;48(3):750–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schiff E, Simsek H, Lee WM, et al. Efficacy and safety of entecavir in patients with chronic hepatitis B and advanced hepatic fibrosis or cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103(11):2776–2783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chang TT, Liaw YF, Wu SS, et al. Long-term entecavir therapy results in the reversal of fibrosis/cirrhosis and continued histological improvement in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology 2010;52(3):886–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yokosuka O, Takaguchi K, Fujioka S, et al. Long-term use of entecavir in nucleoside-naive Japanese patients with chronic hepatitis B infection. J Hepatol 2010;52(6):791–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rockey DC, Caldwell SH, Goodman ZD, et al. Liver biopsy. Hepatology 2009;49(3):1017–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rockey DC, Bissell DM. Noninvasive measures of liver fibrosis. Hepatology 2006;43(2 Suppl 1):S113–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barry-Hamilton V, Spangler R, Marshall D, et al. Allosteric inhibition of lysyl oxidase-like-2 impedes the development of a pathologic microenvironment. Nat Med 2010;16(9):1009–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fontana RJ, Hann HW, Perrillo RP, et al. Determinants of early mortality in patients with decompensated chronic hepatitis B treated with antiviral therapy. Gastroenterology 2002;123(3):719–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schiff ER, Lai CL, Hadziyannis S, et al. Adefovir dipivoxil therapy for lamivudine-resistant hepatitis B in pre- and post-liver transplantation patients. Hepatology 2003;38(6):1419–1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shim JH, Lee HC, Kim KM, et al. Efficacy of entecavir in treatment-naive patients with hepatitis B virus-related decompensated cirrhosis. J Hepatol 2010;52(2):176–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liaw YF, Raptopoulou-Gigi M, Cheinquer H, et al. Efficacy and safety of entecavir versus adefovir in chronic hepatitis B patients with hepatic decompensation: a randomized, open-label study. Hepatology 2011;54(1):91–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liaw YF, Sheen IS, Lee CM, et al. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), emtricitabine/TDF, and entecavir in patients with decompensated chronic hepatitis B liver disease. Hepatology 2011;53(1):62–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chan HL, Chen YC, Gane EJ, et al. Randomized clinical trial: efficacy and safety of telbivudine and lamivudine in treatment-naive patients with HBV-related decompensated cirrhosis. J Viral Hepat 2012;19(10):732–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zoutendijk R, Reijnders JG, Zoulim F, et al. Virological response to entecavir is associated with a better clinical outcome in chronic hepatitis B patients with cirrhosis. Gut 2013;62(5):760–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kim WR, Terrault NA, Pedersen RA, et al. Trends in waiting list registration for liver transplantation for viral hepatitis in the United States. Gastroenterology 2009;137(5):1680–1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Matsumoto A, Tanaka E, Rokuhara A, et al. Efficacy of lamivudine for preventing hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B: A multicenter retrospective study of 2795 patients. Hepatol Res 2005;32(3):173–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Miyake Y, Kobashi H, Yamamoto K. Meta-analysis: the effect of interferon on development of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Gastroenterol 2009;44(5):470–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Papatheodoridis GV, Lampertico P, Manolakopoulos S, et al. Incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B patients receiving nucleos(t)ide therapy: a systematic review. J Hepatol 2010;53(2):348–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Papatheodoridis GV, Manolakopoulos S, Touloumi G, et al. Virological suppression does not prevent the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B patients with cirrhosis receiving oral antiviral(s) starting with lamivudine monotherapy: results of the nationwide HEPNET. Greece cohort study. Gut 2011;60(8):1109–1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Arends P, Sonneveld MJ, Zoutendijk R, et al. Entecavir treatment does not eliminate the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B: limited role for risk scores in Caucasians. Gut 2015;64(8):1289–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]