Abstract

Fatty infiltration and inflammation delay the healing responses and raise major concerns in the therapeutic management of rotator cuff tendon injuries (RCTI). Our evaluations showed the upregulation of ‘metabolic check point’ AMPK and inflammatory molecule, TREM-1 from shoulder biceps tendons collected from RCTI subjects. However, the epigenetic regulation of these biomolecules by miRNAs is largely unknown and it is likely that a deeper understanding of the mechanism of action can have therapeutic potential for RCTI. Based on this background, we have evaluated the miRNAs from RCTI patients with fatty infiltration and inflammation (FI group) and compared with RCTI patients without fatty infiltration and inflammation (No-FI group). NetworkAnalyst was employed to evaluate the genes interconnecting AMPK and TREM-1 pathway, using PRKAA1 (AMPK), TREM-1, HIFlα, HMGB1 and AGER as input genes. The most relevant miRNAs were screened by considering the fold change below - 7.5 and the number of target genes 10 and more which showed 13 miRNAs and 216 target genes. The exact role of these miRNAs in the fatty infiltration and inflammation associated with RCTI is still unknown and the understanding of biological activity of these miRNAs can pave ways to develop miRNA-based therapeutics in the management of RCTI.

Keywords: AMPK signaling, Fatty infiltration, HMGB1, Inflammation, miRNA, Rotator cuff tendon injury, TREM-1

Introduction

Rotator cuff tendon injuries (RCTI), both traumatic and age-related degenerative changes, are one of the most common pathologies of upper extremity. These injuries are both a major health as well as a significant economic problem with more than 250,000 RC repairs being performed in the United States each year [1,2]. Fatty degeneration of rotator cuff (RC) muscles is considered to be a risk factor for successful outcome for rotator cuff surgery [3]. The fatty infiltration always begins in the muscles but, in severe cases proceeds to affect the tendons of the rotator cuff as well as the associated biceps tendon [4]. Little is understood regarding the underlying mechanisms for the fatty infiltration. Goutallier et al. pointed out that the degree of fatty infiltration was directly related to the risk of a poor outcome [5]. Logically, with this background, the next generation of therapeutic approaches for RCTI should include strategies that minimize, prevent or reverse the fatty infiltration.

Inflammation, like fatty infiltration, is also a risk factor for delayed healing responses. Unfortunately, the mechanism of recruitment of inflammatory cells and mediators to the injury site in otherwise hypovascular RC tendon is largely unknown [6]. We have categorized and reported two classes of shoulder biceps tendons; (1) with immune cells (neutrophils and macrophages), and (2) without immune cells. Interestingly, the tissue specimens without immune cells also expressed the pro-inflammatory receptor Triggering Receptors Expressed on Myeloid cells-1 (TREM-1) but, characteristics of classical inflammation was completely absent [7, 8]. Moreover, the cell phenotype responsible for TREM-1 expression has been characterized to be tenocytes. As expected, the protein expression of TREM-1 was found to be higher in the specimens with immune cell infiltration. This suggests TREM-1 to be a key factor for symptomatic and asymptomatic inflammation associated with RCTI [7, 8]. Still, the interrelationship between TREM-1-mediated inflammation and fatty infiltration needs to be elucidated.

The metabolic aspects of fat tissue infiltration in RC tendons have not been studied so far. However, the presence and differentiation of pre-adipocytes in RC muscles have been found to be mediated by the transcription factor, peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) along with CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein-α (C/EBPα) [9]. In addition, AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is the central regulatory enzyme which integrates most of the metabolic pathways depending on the cellular energy status [10]. The active role of AMPK in maintaining the energy homeostasis by preserving mitochondrial function during normal and various cellular stresses has been extensively described in several tissues and cell types [11, 12]. Interestingly, the metabolic and regulatory roles of AMPK regarding fatty infiltration are not being well understood in RC tendon tissues. Moreover, the pathways or molecular events that interlink fat accumulation of RC tendon in terms of AMPK-mediated metabolic homeostasis and TREM-1-mediated inflammation could be a promising a therapeutic target.

Several miRNAs are found to be associated with the regulation of AMPK signaling. For example, miR-451 is proven to control cell proliferation and migration in response to metabolic stress by regulating LKB1 and downstream AMPK [13]. Similarly, miR-195 has also been reported to regulate metabolic homeostasis during the progression of cardiac diseases [14]. However, the reports regarding miRNA regulation associated with TREM-1-mediated inflammation is rare in the literature. Moreover, the epigenetic regulation of fatty infiltration, especially by miRNAs, is still an unexplored topic. Our recent article has reported several key miRNAs associated with ECM disorganization in RCTI patients [15]. In this article, we have used a similar strategy to screen and interlink fatty infiltration and inflammation of RCTI specimens in terms of AMPK and TREM-1 by employing the meta-analysis program NetworkAnalyst. The focus of this article is to integrate AMPK-mediated fatty infiltration and TREM-1-mediated inflammation of RCTI with respect to highly altered miRNAs.

Materials and Methods

RCTI tissue collection and processing

After receiving approval from Institutional Review Board, 8 RCTI patients were recruited to our study and given written informed consent prior to the surgery. In each case the biceps tendon (~3cm length) was surgically removed and temporarily stored in UW (University of Wisconsin) solution. Four out of eight patients were had severe inflammation, glenohumeral arthritis and fatty infiltration in their biceps tendon. These four patients were grouped as Rotator cuff tendon inflammation-fatty infiltration (FI group). The other four had RCTI, but arthritis and signs of inflammation and fatty infiltration were absent (No-FI group). The tissues were used for RNA isolation and immunofluorescence. For immunofluorescence formalin-fixed paraffinized sections of 5μm were used.

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence was performed to assess the expression of AMPK, TREM-1 and HIF1-α by following the procedures described in our recent report [16]. The primary antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotech) used were mouse-anti-human-AMPKα (sc-390579), goat-anti-human-TREM-1 (sc-19309), and mouse-anti-human-HIF1-α (sc-53546), and the secondary antibodies donkey-antimouse-488 (sc-362258) and donkey-anti-goat-488 were used. The fluorescence intensity was quantified by Image J software and expressed as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI).

RNA isolation and microarray detection of miRNAs

RNA was isolated from the fresh pieces (~200mg) of biceps tendon specimens by Trizol method. After quantification, the RNA was used for microarray analysis using miRNA4.0 array following our previously reported protocol [15].

Identification of miRNAs and target genes using NetworkAnalyst

The genes interlinking AMPK signaling and TREM-1 pathway were assessed by NetworkAnalyst program based on the published gene database [17, 18]. The input genes used for NetworkAnalyst analysis were PRKAA1 (AMPK), TREM-1, HIF1-α, HMGB1 and AGER. Since the RC tendons are highly susceptible to hypoxia after RCTI, HIF1-α gene was used as an input. HMGB1 and AGER (RAGE), the potential ligands of TREM-1, were also given as input. From the list of resulting genes, individual symbol of genes was used as the search key word for screening their target miRNA from the miRNA-array data. Microsoft EXCEL-2007 was used for screening the miRNA targets [15].

Statistics

The average intensity of three-to-four different sections of each specimen was quantified and averaged for each experimental group. The fluorescent intensity values (MFI) were expressed as mean ± SD and the level of significance was set at p<0.05 by unpaired t test (non-parametric, Mann Whitney U test) using GraphPad Prism software.

Results

Immunofluorescence

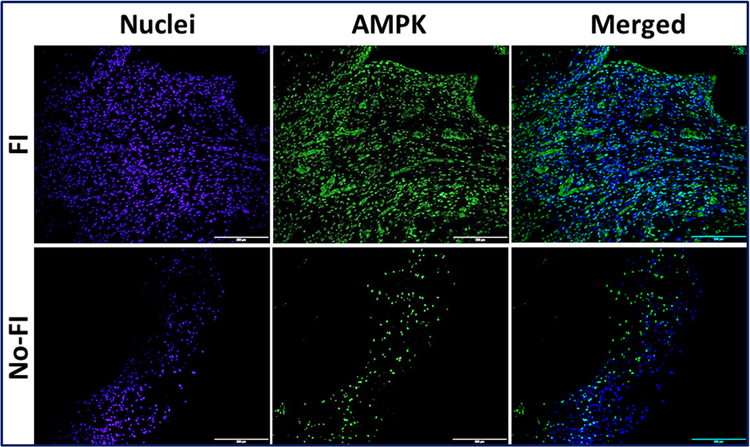

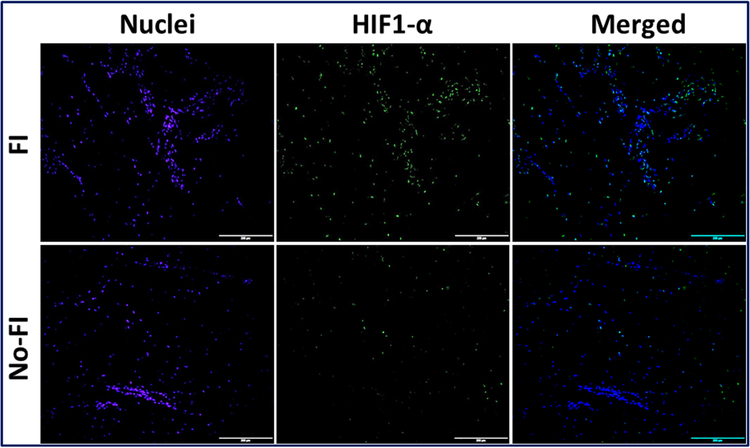

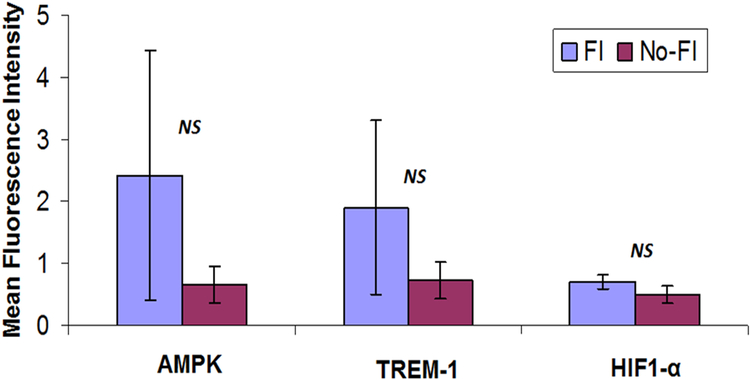

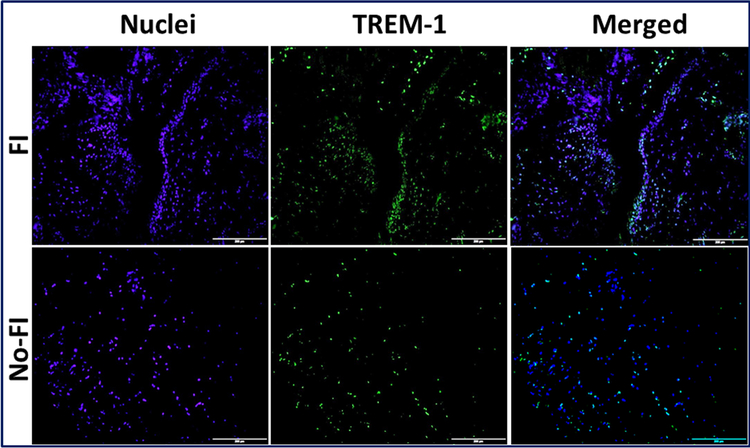

The differential expression of AMPK, TREM-1 and HIF1-α were observed in the immunofluorescence analysis (Figs. 1–3). Expression of these genes was quantified using Image J software from the fluorescence intensity (Fig. 4). The results were documented as Mean Fluorescence Intensity (MFI). The average expression in FI group was found to be greater than No-FI group, but not statically significant. The result, however, reflects the higher expression of AMPK, TREM-1 and HIF1-α in FI group which could be the contributing factor for fatty infiltration and TREM-1-mediated inflammation.

Figure 1:

Immunofluorescence analysis for the expression of AMPK1a showing increased expression in FI group compared to the No-FI group. Figure represents similar expression pattern in all 4 patients from each group. Images in the top row are histological sections of patient biopsies from the FI group, and images in the bottom row are histological sections of patient biopsies from the No-FI group. Images in the left column show nuclear staining with DAPI; the images in the middle column show expression of AMPK while the images in the right column show overlay of AMPK staining with DAPI. Images were acquired at 20x magnification using CCD camera attached to the Olympus microscope.

Figure 3:

Immunofluorescence analysis for the expression of HIF-1α showing increased expression in FI group compared to the No-FI group. Figure represents similar expression pattern in all 4 patients from each group. Images in the top row are histological sections of patient biopsies from the FI group, and images in the bottom row are histological sections of patient biopsies from the No-FI group. Images in the left column show nuclear staining with DAPI; the images in the middle column show expression of AMPK while the images in the right column show overlay of AMPK staining with DAPI. Images were acquired at 20x magnification using CCD camera attached to the Olympus microscope.

Figure 4:

The image shows quantification of gene expression in Figures 1, 2, and 3. The intensity of gene expression as observed through immunofluorescence was acquired and the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) was quantified from five randomly selected independent fields. The graphs represent MFI mean values with standard error.

Evaluation of genes by NetworkAnalyst and screening of miRNAs

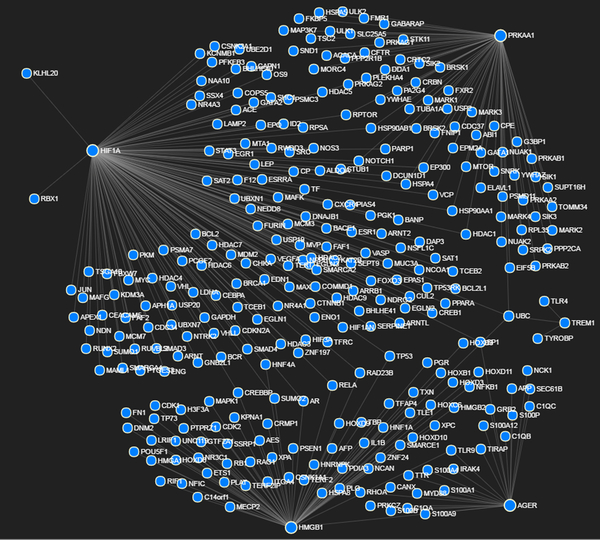

The NetworkAnalyst assessment, using PRKAA1 (AMPK), TREM-1, HIF1α, HMGB1 and AGER (RAGE) as input genes, revealed the interlinked network of 301 genes (Fig. 5; Table 1) that contribute to 120 pathways (Supplementary Table 1). Among them, nine pathways were found to be highly associated with metabolic homeostasis and inflammation which altogether are constituted by 164 genes (neglecting the repeated genes it was found to be 114 genes) (Supplementary Table 2). The microarray results showed considerable alteration of miRNAs between the two groups. The relative fold-change in the miRNA expression ranged from −71.26 to +5.57 and the miRNAs of fold-change between −3 to −71.26 and +2 to +5.57 were screened to predict the interaction of specific genes associated with AMPK, TREM-1, HIF1-α, HMGB1 and AGER, as revealed by NetworkAnalyst. The miRNAs with fold-change between −3 to +2 were omitted from the screening as these miRNAs were expected to elicit minimal effects in the pathogenesis of the tendon. Altogether, 1532 miRNAs were found to be altered upon compiling the NetworkAnalyst data with the microarray data (Supplementary Table 3). The 105 miRNAs were found to have seven or more target genes and they altogether form 1217 target miRNAs (Supplementary Table 4). To further screen the most relevant miRNAs, the fold-change below −7.5 and the number of target genes 10 and more were considered. The results revealed 12 downregulated miRNAs and one upregulated miRNA where these 13 miRNAs were found to be associated with 216 genes (Table 2).

Figure 5:

Figure shows potential interactions between PRKAA1 (AMPK), TREM-1, HIF1α, HMGB1 and AGER as determined by NetworkAnalyst program.

Table 1:

NetworkAnalyst assessment showing the interlinked network of 301 genes using PRKAA1 (AMPK), TREM-1, HIF1α, HMGB1 and AGER (RAGE) as input genes.

| Id | Label |

|---|---|

| Q16665 | HIF1A |

| Q13131 | PRKAA1 |

| P09429 | HMGB1 |

| Q15109 | AGER |

| P0CG48 | UBC |

| Q9NP99 | TREM1 |

| P08047 | SP1 |

| Q92793 | CREBBP |

| P61956 | SUMO2 |

| P54727 | RAD23B |

| P04637 | TP53 |

| P10275 | AR |

| P41235 | HNF4A |

| Q04206 | RELA |

| P55072 | VCP |

| Q09472 | EP300 |

| P46531 | NOTCH1 |

| P07900 | HSP90AA1 |

| Q13547 | HDAC1 |

| Q8N122 | RPTOR |

| P08238 | HSP90AB1 |

| P34932 | HSPA4 |

| P09874 | PARP1 |

| Q9UQL6 | HDAC5 |

| Q9NR96 | TLR9 |

| Q9UKR5 | C14orf1 |

| Q14194 | CRMP1 |

| Q13438 | OS9 |

| P02766 | TTR |

| O43914 | TYROBP |

| 000206 | TLR4 |

| Q13485 | SMAD4 |

| P04271 | S100B |

| 094888 | UBXN7 |

| P16333 | NCK1 |

| P62993 | GRB2 |

| P08651 | NFIC |

| Q9UN36 | NDRG2 |

| Q9Y5B9 | SUPT16H |

| P61586 | RHOA |

| Q8IYT8 | ULK2 |

| O95166 | GABARAP |

| P17096 | HMGA1 |

| P17028 | ZNF24 |

| Q08117 | AES |

| P52655 | GTF2A1 |

| P00750 | PLAT |

| P25815 | S100P |

| P27695 | APEX1 |

| Q9UNE7 | STUB1 |

| P62258 | YWHAE |

| P30101 | PDIA3 |

| P57059 | SIK1 |

| P49815 | TSC2 |

| P03372 | ESR1 |

| P26447 | S100A4 |

| P24941 | CDK2 |

| Q92905 | COPS5 |

| Q13950 | RUNX2 |

| P51668 | UBE2D1 |

| Q8WUI4 | HDAC7 |

| Q15554 | TERF2 |

| P49427 | CDC34 |

| Q96SW2 | CRBN |

| Q9NYB0 | TERF2IP |

| Q01664 | TFAP4 |

| P38398 | BRCA1 |

| P07384 | CAPN1 |

| Q15785 | TOMM34 |

| O43318 | MAP3K7 |

| P23025 | XPA |

| O94966 | USP19 |

| Q9UKV0 | HDAC9 |

| Q15717 | ELAVL1 |

| Q99814 | EPAS1 |

| Q96GG9 | DCUN1D1 |

| P13612 | ITGA4 |

| P49768 | PSEN1 |

| P02751 | FN1 |

| P23297 | S100A1 |

| P49407 | ARRB1 |

| P78362 | SRPK2 |

| P28482 | MAPK1 |

| Q5UIP0 | RIF1 |

| Q13432 | UNC119 |

| O60224 | SSX4 |

| P40337 | VHL |

| P20226 | TBP |

| Q16543 | CDC37 |

| P54619 | PRKAG1 |

| Q9Y478 | PRKAB1 |

| P05141 | SLC25A5 |

| P11021 | HSPA5 |

| O43741 | PRKAB2 |

| Q92831 | KAT2B |

| Q9H6Z9 | EGLN3 |

| Q9NWT6 | HIF1AN |

| O15350 | TP73 |

| O14818 | PSMA7 |

| Q96KS0 | EGLN2 |

| Q9GZT9 | EGLN1 |

| Q13330 | MTA1 |

| P68400 | CSNK2A1 |

| P41227 | NAA10 |

| Q5T3J3 | LRIF1 |

| Q13617 | CUL2 |

| P17813 | ENG |

| P84022 | SMAD3 |

| P15692 | VEGFA |

| P27540 | ARNT |

| Q9HBZ2 | ARNT2 |

| P11474 | ESRRA |

| Q92585 | MAML1 |

| O43524 | FOXO3 |

| Q9Y3V2 | RWDD3 |

| Q96CS3 | FAF2 |

| P01588 | EPO |

| P16220 | CREB1 |

| P23769 | GATA2 |

| P05305 | EDN1 |

| P05412 | JUN |

| P02787 | TF |

| P02786 | TFRC |

| P04075 | ALDOA |

| P06733 | ENO1 |

| P05121 | SERPINE1 |

| Q07869 | PPARA |

| P00558 | PGK1 |

| O14503 | BHLHE40 |

| Q9C0J9 | BHLHE41 |

| O14746 | TERT |

| P16860 | NPPB |

| Q16620 | NTRK2 |

| Q16875 | PFKFB3 |

| P41159 | LEP |

| P00450 | CP |

| Q02363 | ID2 |

| P29474 | NOS3 |

| P04406 | GAPDH |

| P09958 | FURIN |

| Q96BI3 | APH1A |

| P56817 | BACE1 |

| P61073 | CXCR4 |

| Q07817 | BCL2L1 |

| P08865 | RPSA |

| P10599 | TXN |

| Q9UHD8 | SEPT9 |

| P52294 | KPNA1 |

| P12821 | ACE |

| P18146 | EGR1 |

| P35790 | CHKA |

| P06731 | CEACAM5 |

| P40763 | STAT3 |

| Q02505 | MUC3A |

| Q14764 | MVP |

| Q9Y2N7 | HIF3A |

| P35222 | CTNNB1 |

| Q00987 | MDM2 |

| O15379 | HDAC3 |

| P01584 | IL1B |

| P20823 | HNF1A |

| P02771 | AFP |

| P80511 | S100A12 |

| P51532 | SMARCA4 |

| P29353 | SHC1 |

| P51531 | SMARCA2 |

| Q9UGJ0 | PRKAG2 |

| Q9UQ80 | PA2G4 |

| P56524 | HDAC4 |

| Q8N9N5 | BANP |

| Q9Y2K6 | USP20 |

| P06493 | CDK1 |

| P54646 | PRKAA2 |

| P63165 | SUMO1 |

| Q96F10 | SAT2 |

| P42766 | RPL35 |

| O75385 | ULK1 |

| P51116 | FXR2 |

| Q9UBN7 | HDAC6 |

| Q15369 | TCEB1 |

| Q7KZF4 | SND1 |

| O60841 | EIF5B |

| Q06787 | FMR1 |

| Q13283 | G3BP1 |

| Q9BW61 | DDA1 |

| P48729 | CSNK1A1 |

| Q8N2W9 | PIAS4 |

| P16870 | CPE |

| Q8IZP0 | ABI1 |

| P14921 | ETS1 |

| P49715 | CEBPA |

| Q05513 | PRKCZ |

| Q99836 | MYD88 |

| P58753 | TIRAP |

| Q9NWZ3 | IRAK4 |

| Q04724 | TLE1 |

| O14594 | NCAN |

| P23471 | PTPRZ1 |

| P15918 | RAG1 |

| P06400 | RB1 |

| P13569 | CFTR |

| P61978 | HNRNPK |

| P51608 | MECP2 |

| P04150 | NR3C1 |

| P06401 | PGR |

| P17980 | PSMC3 |

| O14709 | ZNF197 |

| O00327 | ARNTL |

| P61244 | MAX |

| P84243 | H3F3A |

| Q9Y230 | RUVBL2 |

| P01106 | MYC |

| P25205 | MCM3 |

| Q6RSH7 | VHLL |

| P33993 | MCM7 |

| P22736 | NR4A1 |

| P21673 | SAT1 |

| P63244 | GNB2L1 |

| Q15788 | NCOA1 |

| P19838 | NFKB1 |

| Q92769 | HDAC2 |

| P51398 | DAP3 |

| P67775 | PPP2CA |

| P27448 | MARK3 |

| P63104 | YWHAZ |

| Q9H0K1 | SIK2 |

| Q9H093 | NUAK2 |

| O75604 | USP2 |

| Q96L34 | MARK4 |

| Q969H0 | FBXW7 |

| Q7KZI7 | MARK2 |

| P26583 | HMGB2 |

| Q01860 | POU5F1 |

| Q15370 | TCEB2 |

| Q8TDC3 | BRSK1 |

| Q04323 | UBXN1 |

| Q71U36 | TUBA1A |

| Q9NRH2 | SNRK |

| Q9UNN5 | FAF1 |

| Q8N668 | COMMD1 |

| Q8IWQ3 | BRSK2 |

| O60285 | NUAK1 |

| P30154 | PPP2R1B |

| Q9UNZ2 | NSFL1C |

| Q9P0L2 | MARK1 |

| P50570 | DNM2 |

| P11142 | HSPA8 |

| Q9Y2K2 | SIK3 |

| Q8TF40 | FNIP1 |

| P14651 | HOXB3 |

| P31277 | HOXD11 |

| P28358 | HOXD10 |

| P00747 | PLG |

| P31249 | HOXD3 |

| P14653 | HOXB1 |

| P09630 | HOXC6 |

| P13378 | HOXD8 |

| P28356 | HOXD9 |

| P42345 | MTOR |

| Q8N726 | CDKN2A |

| Q8TE76 | MORC4 |

| Q9H4M7 | PLEKHA4 |

| P14618 | PKM |

| P00338 | LDHA |

| Q9Y2M5 | KLHL20 |

| Q96S44 | TP53RK |

| P35227 | PCGF2 |

| P15976 | GATA1 |

| Q9BZW7 | TSGA10 |

| P02745 | C1QA |

| P02747 | C1QC |

| P02746 | C1QB |

| Q16558 | KCNMB1 |

| Q92570 | NR4A3 |

| P50552 | VASP |

| P06702 | S100A9 |

| P00748 | F12 |

| O95278 | EPM2A |

| Q15843 | NEDD8 |

| Q15185 | PTGES3 |

| Q99608 | NDN |

| P05067 | APP |

| Q01831 | XPC |

| P27824 | CANX |

| P10415 | BCL2 |

| P13473 | LAMP2 |

| P60468 | SEC61B |

| Q53ET0 | CRTC2 |

| P25685 | DNAJB1 |

| Q15831 | STK11 |

| P11274 | BCR |

| O00231 | PSMD11 |

| Q9Y4C1 | KDM3A |

| O15525 | MAFG |

| O60675 | MAFK |

| P62877 | RBX1 |

| Q08945 | SSRP1 |

| P12931 | SRC |

| Q969G3 | SMARCE1 |

| Q13451 | FKBP5 |

| Q13085 | ACACA |

Table 2:

Thirteen highly significant miRNAs and associated 216 genes screened from FI vs No-FI miRNA microarray data.

| miRNAs | FC | No. of hits |

|---|---|---|

| hsa-miR-145-5p | −55.42 | 13 |

| hsa-miR-99a-5p | −51.68 | 12 |

| hsa-miR-100-5p | −51.6 | 14 |

| hsa-miR-150-5p | −23.41 | 18 |

| hsa-miR-193b-3p | −20.35 | 14 |

| hsa-miR-103a-3p | −14.87 | 14 |

| hsa-miR-31-5p | −14.44 | 14 |

| hsa-miR-195-5p | −14.04 | 22 |

| hsa-miR-497-5p | −12.3 | 20 |

| hsa-miR-15a-5p | −10.66 | 19 |

| hsa-miR-16-5p | −7.98 | 28 |

| hsa-let-7b-5p | −7.73 | 18 |

| hsa-miR-297 | 3.81 | 10 |

| Total 216 | ||

Discussion

Fat tissue accumulation associated with RCTI predominantly localizes to interstitial/epimysial compartments of RC muscles as well as in the injured tendon. This impairs the tendon physiology and mechanics and delays the healing response possibly by activating inflammation. The increased lipid content in the RC tendon makes the tendon-muscle unit stiff and inflamed [19]. Apart from the accumulation of triglycerides, the pre-existence and proliferation of adipocytes/adipogenic cells have also been established in RC tendons [19,20]. Molecular mediators, like peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPAR- α) and AMPK, have been reported to play significant role in regulating fat metabolism in most tissues [4, 21]. However, there is limited information on the signaling pathways that interrelate fat metabolism and inflammation of RC tendon.

In our study, two out of four patients in the FI group exhibited severe FI, similar to the findings in our earlier publication [15]. Interestingly, the patients of FI group expressed higher level of AMPK along with the higher TREM-1 expression than in the non-FI group, which exhibited minimal expression of these two mediators. We also reported the dual mode of TREM-1-mediated inflammation and the role of HMGB1 and RAGE in RC tendons [16]. Simultaneous upregulation of AMPK and TREM-1 in patients with FI could be an indication of the possibilities of common regulatory molecules linking metabolic homeostasis with inflammation. The focus of this article is to elucidate the epigenetic relationship between AMPK-mediated fat metabolism and TREM-1-mediated inflammation by screening the associated genes and regulatory miRNAs in RCTI subjects.

The gene expression patterns during physiology and pathology are under the influence of miRNAs at the transcription level. Cellular miRNAs alter genes during pathological conditions and the knowledge of the specific genes that are involved in pathogenesis is necessary for evaluating the associated miRNAs [22, 23, 24]. Most diseases have multiple gene products and signaling pathways acting at a molecular level. Similarly, most miRNAs have multiple targets which warrant careful screening to validate the interactions between miRNAs and their target mRNA/mRNAs. The understanding of multiple miRNA targets and the correlation with the interrelated genes associated with pathology is essential to evaluate the therapeutic potentials of miRNAs.

Analysis of biological network of gene signaling requires selection of key genes, knowledge of their network and scoring their interrelation with the genes of multiple signaling pathways which requires tedious search and analysis. The meta-analysis online-program NetworkAnalyst simplifies the search and integrates the genes and pathways associated with the input genes and present the results in a proper visualization mode [17]. We have given PRKAA1 (AMPK), TREM-1, HIF1α, HMGB1 and AGER as input genes to visualize the network of interconnected genes and pathways (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 2). The NetworkAnalyst data were utilized to screen the miRNAs from the miRNA array data of RCTI specimen which narrowed down the number of miRNAs from 1532 to highly relevant 13 miRNAs. These 13 miRNAs might have significant role in the fatty infiltration and inflammation associated with RCTI.

Hsa-miR-145–5p is a highly downregulated (−55.42) miRNA as obtained from our search. Hsa-miR-145–5p has been reported to be involved in anti-inflammatory mechanisms by suppressing cytokines IL-β, TNF-α, and IL-6 especially under hypoxic conditions. Also, during hypoxia, hsa-miR-145–5p also exhibits an anti-apoptotic role [25, 26]. The potential target of hsa-miR-145–5p was identified to be CD40 in cardiac cells [25]. The information regarding hsa-miR-145–5p regulation of AMPK signaling is not available in the literature. Moreover, the hsa-miR-145–5p has been reported to be associated with cancer biology [27]. Also, the miR-145 targets Myd88 of TLR4 signaling and regulate inflammatory responses [28]. However, the impact of this miRNA in inflammation and TREM-1 signaling is largely unknown. We have already identified the potential relationship of hsa-miR-145–5p with ECM disorganization as its downregulation correlated with the extent of matrix disorganization [15]. Taken together, the replenishment of hsa-miR-145–5p in RCTI sites can be beneficial owing to its antiinflammatory and anti-apoptotic effects.

Hsa-miR-99a-5p and hsa-miR-100–5p were downregulated to more than 50-fold change and possessed 12 and 14 targets, respectively. These two miRNA families were reported to be involved in the activation of mTOR, which is negatively regulated by AMPK [29]. However, miR-99b family is activated by TGF-β signaling and activation of which inhibits IGF-1/mTOR signaling by downregulating AKT1, IGF1R and mTOR [30]. The understanding of antagonistic effects of miR-99a and miR-99b requires more research. Hsa-miR-99a-5p and hsa-miR-100–5p were also found to be increased in the serum of patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infections; but their involvement in immune response is yet to be unveiled [31]. The direct role of hsa-miR-99a-5p and hsamiR-100–5p in the regulation of AMPK and TREM-1 in tendon tissue is unknown.

Hsa-miR-150–5p is another highly altered (downregulated 23.41-fold change) miRNA in our RCTI patient specimen with 18 target genes. The transfection of miR-150–5p to multiple myeloma cell line MM1S significantly altered the expression of AMPK, which, in turn, is mediated by glucocorticoid receptor protein [32]. Moreover, serum miR-150–5p level has been developed as a diagnostic marker for Myasthenia Gravis [33]. The role of miR-150–5p in the maturation of B and T cells and its implications in ulcerative colitis have also been established [34]. Downregulation of hsa-miR-150–5p after H1N1 challenge in porcine white blood cells signifies its role in immune response, however the actual mechanism of action or target mRNAs are largely unknown [35]. In addition, upregulation of circulatory hsa-miR-150–5p has been observed in inflammation associated with exercise which could have implications with musculoskeletal biology. However, the reports regarding the direct involvement of AMPK signaling and TREM-1 pathway in RCTI or other diseases is not available.

Each of the miRNAs, Hsa-miR-193b-3p, hsa-miR-103a-3p and hsa-miR-31–5p, were found to have 14 target genes, as evident from our screening data. Hsa-miR-193b-3p was reported to be associated with several cancers especially in breast cancer [36]. The target of hsa-miR-103a-3p has been identified to be the UTR region of GPRC5A gene (G-protein coupled receptor) and the targeted downregulation of hsa-miR-103a-3p recovered the cells from oncogenesis. Hsa-miR-193b-3p also plays a role in cell division, metabolism, stress responses and blood vessel formation and has been associated with diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease [37]. MiRNAs of mir-103 family also plays vital role in adipose tissue metabolism and type 2 diabetes development. Silencing of miR-103 restored glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity in experimental mice and human tissues. Mir-103 promotes lipolysis by repressing the caveolin-1 mRNA and destabilizes insulin receptors leading to insulin resistance in the adipocytes [38, 39]. On the other hand, the upregulation of miR-31 silenced the adipogenic biomarkers like PPAR-γ, CEBPA, and AP2. MiR-31 binds putatively to the 3’UTR of CEBPA (which binds to the enhancer region of leptin gene) and the subsequently suppress leptin and leads to fat mobilization [39]. In contrast, the downregulation of miR-31 during adipogenesis has also been reported. This could be due to the possible binding to the predicted target, phosphoinositide-3-kinase, class 2, alpha polypeptide (PIK3C2A). However, the direct involvement of these three miRNAs in AMPK and TREM-1 signaling is largely unknown. Their high fold-change and number of target genes suggest their role in fatty infiltration and inflammation associated with RCTI which warrants further research.

Has-miR-195–5p was found to have 22 target genes as evident from our data set. MiR-195 has been reported to be downregulated in carcinoma of various organs like liver, stomach, bladder, and breast. The evidence from in vitro cell culture studies revealed that the anti-tumorigenic effect of miR-195 proceeds by the regulation of G1/S transition of cell cycle. Recently, PHF19 (PHD finger protein 19) has been identified as a potential target for miR-195 [40]. In addition, ribosomal protein S6 kinase, 70kDa, polypeptide 1 (RPS6KB1) has also been found to be another target in prostate cancer cells [41]. Also, miR-195 prevents the migration and invasion of prostate cancer cells by targeting the cell mobility regulator, Fra1[40]. A recent study correlates cancer associated inflammation with miR-195 expression in regard to its effects on TNF-α/NF-κβ signaling [42, 43]. Even though, miR-195 is involved in cancer associated inflammation, its role in TREM-1 signaling has not been studied yet. Interestingly, miR-195 also targets the 3’UTR of GLUT3 resulting in decreased glucose intake in T24 cells [44]. In response to saturated fatty acid and high fat diet, the upregulation of miR-195 occurs and insulin receptor has been reported to be the target. So, the upregulation of miR-195 impairs insulin signaling and glycogen synthesis [45]. But, the role of miR-195 in AMPK signaling has not been explored yet in any tissue types. However, we speculate that there could be a direct/indirect involvement of miR-195 in AMPK signaling as insulin signaling is regulated by AMPK. More studies are required to validate this phenomenon.

Our data revealed the downregulation of hsa-miR-497–5p (20 targets) and hsamiR-15a-5p (20 targets) with −12.3 and −10.66-fold change, respectively. Hsa-miR-497–5p was reported to inhibit G1/S phase of hepatocarcinoma cells and inhibits cancer proliferation. IGF-1 has been identified to be a potential target for hsa-miR-497–5p. Furthermore, there are reports suggesting the role of hsa-miR-497–5p in apoptosis by regulating Bcl family of genes and also in fibrotic reactions [46]. Studies using bioinformatics tools predicted SMAD3 to be a target for hsa-miR-497–5p and was confirmed to bind at the 3’UTR. The binding favors cell cycle arrest at G0/G1 phase. Since SMAD3 is a key regulator for TGF-β signaling, hsa-miR-497–5p can be correlated with inflammatory and healing responses. However, more studies are needed to elucidate this hypothesis [47, 48]. On the other hand, hsa-miR-15a-5p plays a significant role in the inhibition of inflammatory mediators associated with diabetic retinopathy [49]. This can be correlated with the increased inflammation in our RCTI-FI patients, as there was a tenfold downregulation of this miRNA. Hsa-miR-15a-5p also regulates Bcl2 family of genes and supposed to have role in apoptosis which warrants more investigation [50, 51]. Yes- associated protein 1 (YAP1) was found to be a target for hsa-miR-15a-5p and the downregulation of this miRNA impaired fat metabolism in goat mammary epithelial cells. This miRNA is expected to have role in the differentiation of adipocyte to facilitate milk fat synthesis [52]. However, the reports relating the involvement of these two miRNAs in AMPK and TREM-1 signaling are unavailable in the literature.

CCND1 (Cyclin D1), Bcl2 (B-cell lymphoma 2), serotonin transporter (SERT/SLC6A4) and RPS6KB1 (Ribosomal protein S6) were found to be targets for hsamiR-16–5p. This miRNA has been considered as a housekeeping miRNA and is being used as an endogenous control for silencing/expression studies [53, 54]. It is considered as a biomarker to detect the prognosis of gastric cancer [55]. Also, circulating levels of hsa-miR-16–5p was also found to be increased in hypertension [56]. The inflammatory role of hsa-miR-16–5p is evident by its upregulation in the presence of TNF-α [57].

Similarly, hsa-let-7b-5p acts in response to oxidized-LDL by targeting through B-cell lymphoma extra-large (Bcl-xL) [58]. Hsa-miR-16–5p is also associated with the translational control of insulin receptor substrate 2, LDL receptor, hepatic lipoprotein lipase and SNAP23 which are involved in steatosis [59]. Basigin has been identified to be another target for hsa-let-7b-5p showing its role in the inhibition of invasion of several carcinomas [60]. The serum level of this miRNA is correlated with CRP concentration, an inflammatory biomarker [61]. Hsa-let-7b-5p suppresses TLR4 mRNA and prevents NF-kB activation and downstream signaling. It also inhibits type 1 IFN production and inhibits the replication of several viruses by inhibiting insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding protein-1. Moreover, IL-6 production was found to be decreased with the increased expression of let-7b showing its immunomodulatory function [62]. Apart from these, hsa-miR-297 is the only upregulated miRNA observed in our screening. The biological functions and the potential target genes have not been clarified yet. However, hsa-miR-297 targets CD28 which activates the production of IL-4 and IL-10 in T cells [63, 64].

Most miRNAs presented in this article have not been studied for their effect on RCTI. Several of them, however, have been reported to have impact on cell and cancer biology. Although the miRNAs, with AMPK and TREM-1 as direct target, were not detected in our data yet, many of these miRNAs were reported to have active role in lipid metabolism which can have implications to AMPK signaling. Moreover, these miRNAs may have_role in the lipid metabolism of tendon cells and the alterations in their expression level could be the reason for the accumulation of fat tissue in RC tendons. In addition, these miRNAs have role in stem cell migration, differentiation and proliferation. Also, the_involvement of these miRNAs in the recruitment and functioning of adipose progenitor cells to injured RC tendon cannot be ignored. On the other hand, miRNAs targeting TREM-1-mediated inflammation has not been identified from our data. Nonetheless, most of these miRNAs have target genes associated with other inflammatory pathways which can be interconnected to TREM-1 pathway. Our focus was to screen those miRNAs associated with the genes interlinking AMPK and TREM-1 signaling. The cumulative effect of these miRNAs could have played role in the initiation and progression of FI and inflammation, the two hallmarks of severe RCTI. Further information of the underlying mechanism, function and regulation of these miRNAs will improve our understanding regarding the pathogenesis and pathophysiology of RCTI and can pave ways to develop miRNA-based therapeutics in the management of RCTI.

This study has several limitations. We analyzed only 4 patients from each group and the variability among the subjects resulted in statistically non-significant results. Also, it is very difficult to obtain normal shoulder tendon for comparison. The yield of the RNA and protein was very low due to the highly collagenous nature and low cellularity which prevented from performing mRNA studies and Western blot analysis. Moreover, the medical and social history of patients was unknown, especially in regard to the activity level, nutritional status, drug intake and other co-morbidities such as diabetes, obesity and others. The major focus of the study was to screen the miRNAs from the tendon tissues of RCTI patients with and without FI based on their fold-change. However, the translational significance and mechanistic aspects of these miRNAs warrants further investigation.

Conclusions

The network analysis of genes associated with AMPK and TREM-1 signaling using the NetworkAnalyst meta-analysis program revealed the involvement of 114 genes in metabolic homeostasis and inflammation of rotator cuff tendon injuries. Compiling the miRNA-array data and these 114 genes showed the alteration in 1532 miRNAs. Considering fold-change and number of targets the screening was narrowed down to 13 miRNAs (hsa-miR-145–5p, hsa-miR-99a-5p, hsa-miR-100–5p, hsa-miR-150–5p, hsamiR-193b-3p, hsa-miR-103a-3p, hsa-miR-31–5p, hsa-miR-195–5p, hsa-miR-497–5p, hsamiR-15a-5p, hsa-miR-16–5p, hsa-let-7b-5p and hsa-miR-297) with altogether 216 target genes. These 13 miRNAs are believed to be associated with the pathogenesis of RCTI and warrant detailed evaluation for their therapeutic potential.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1. NetworkAnalyst evaluation showing the interlinked network of 120 pathways associated with PRKAA1 (AMPK), TREM-1, HIF1α, HMGB1 and AGER (RAGE).

Supplementary Table 2. Nine pathways associated with metabolic homeostasis and inflammation based on AMPK and TREM-1 and their corresponding genes as determined by NetworkAnalyst.

Supplementary Table-3. miRNAs associated with 114 genes from nine pathways associated with metabolic homeostasis and inflammation based on AMPK and TREM-1 from RCTI subjects.

Supplementary Table-4. miRNAs from RCTI patients (FI vs No-FI) having seven or more target genes.

Figure 2:

Immunofluorescence analysis for the expression of TREM-1 showing increased expression in FI group compared to the No-FI group. Figure represents similar expression pattern in all 4 patients from each group. Images in the top row are histological sections of patient biopsies from the FI group, and images in the bottom row are histological sections of patient biopsies from the No-FI group. Images in the left column show nuclear staining with DAPI; the images in the middle column show expression of AMPK while the images in the right column show overlay of AMPK staining with DAPI. Images were acquired at 20x magnification using CCD camera attached to the Olympus microscope.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the State of Nebraska LB506 grant to DKA and Creighton University LB692 grant to MFD. The research work of DK Agrawal is also supported by R01HL116042, R01HL120659 and R01HL144125 awards from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, USA. The content of this original research article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the State of Nebraska.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Luan T, Liu X, Easley JT, et al. (2015) Muscle atrophy and fatty infiltration after an acute rotator cuff repair in a sheep model. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J 5:106–112 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oak NR, Gumucio JP, Flood MD, et al. (2014) Inhibition of 5-LOX, COX-1, and COX-2 Increases Tendon Healing and Reduces Muscle Fibrosis and Lipid Accumulation After Rotator Cuff Repair. Am J Sports Med 42:2860–2868 . doi: 10.1177/0363546514549943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laron D, Samagh SP, Liu X, et al. (2012) Muscle degeneration in rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 21:164–174 . doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.09.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thankam FG, Dilisio MF, Agrawal DK (2016) Immunobiological factors aggravating the fatty infiltration on tendons and muscles in rotator cuff lesions. Mol Cell Biochem 417:17–33. doi: 10.1007/s11010-016-2710-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goutallier D, Postel J-M, Gleyze P, et al. (2003) Influence of cuff muscle fatty degeneration on anatomic and functional outcomes after simple suture of fullthickness tears. J Shoulder Elb Surg Am Shoulder Elb Surg Al 12:550–554 . doi: 10.1016/S1058274603002118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thankam FG, Dilisio MF, Agrawal DK (2016) Immunobiological factors aggravating the fatty infiltration on tendons and muscles in rotator cuff lesions. Mol Cell Biochem. doi: 10.1007/s11010-016-2710-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thankam FG, Dilisio MF, Dietz NE, Agrawal DK (2016) TREM-1, HMGB1 and RAGE in the Shoulder Tendon: Dual Mechanisms for Inflammation Based on the Coincidence of Glenohumeral Arthritis. PLOS ONE 11:e0165492 . doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rees JD (2006) Current concepts in the management of tendon disorders. Rheumatology 45:508–521 . doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joshi SK, Liu X, Samagh SP, et al. (2013) mTOR regulates fatty infiltration through SREBP-1 and PPARγ after a combined massive rotator cuff tear and suprascapular nerve injury in rats. J Orthop Res Off Publ Orthop Res Soc 31:724–730 . doi: 10.1002/jor.22254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang LQ, De Castro Barbosa T, Massart J, et al. (2015) Diacylglycerol Kinase δ Regulates AMPK Signaling, Lipid Metabolism and Skeletal Muscle Energetics. Am J Physiol - Endocrinol Metab ajpendo.00209.2015 . doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00209.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hardie DG (2011) AMP-activated protein kinase: an energy sensor that regulates all aspects of cell function. Genes Dev 25:1895–1908 . doi: 10.1101/gad.17420111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hardie DG (2008) AMPK: a key regulator of energy balance in the single cell and the whole organism. Int J Obes 32:S7–S12 . doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Godlewski J, Nowicki MO, Bronisz A, et al. (2010) MicroRNA-451 Regulates LKB1/AMPK Signaling and Allows Adaptation to Metabolic Stress in Glioma Cells. Mol Cell 37:620–632 . doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.02.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen H, Untiveros GM, McKee LAK, et al. (2012) Micro-RNA-195 and −451 Regulate the LKB1/AMPK Signaling Axis by Targeting MO25. PLoS ONE 7:e41574 . doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thankam FG, Boosani CS, Dilisio MF, et al. (2016) MicroRNAs Associated with Shoulder Tendon Matrisome Disorganization in Glenohumeral Arthritis. PLOS ONE 11:e0168077 . doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0168077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thankam FG, Dilisio MF, Dietz NE, Agrawal DK (2016) TREM-1, HMGB1 and RAGE in the Shoulder Tendon: Dual Mechanisms for Inflammation Based on the Coincidence of Glenohumeral Arthritis. PLOS ONE 11:e0165492 . doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xia J, Gill EE, Hancock REW (2015) NetworkAnalyst for statistical, visual and network-based meta-analysis of gene expression data. Nat Protoc 10:823–844 . doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xia J, Benner MJ, Hancock REW (2014) NetworkAnalyst - integrative approaches for protein-protein interaction network analysis and visual exploration. Nucleic Acids Res 42:W167–W174 . doi: 10.1093/nar/gku443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chaudhury S, Dines JS, Delos D, et al. (2012) Role of fatty infiltration in the pathophysiology and outcomes of rotator cuff tears. Arthritis Care Res 64:76–82 . doi: 10.1002/acr.20552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsumoto F, Uhthoff HK, Trudel G, Loehr JF (2002) Delayed tendon reattachment does not reverse atrophy and fat accumulation of the supraspinatus — an experimental study in rabbits. J Orthop Res 20:357–363 . doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(01)00093-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steinbacher P, Tauber M, Kogler S, et al. (2010) Effects of rotator cuff ruptures on the cellular and intracellular composition of the human supraspinatus muscle. Tissue Cell 42:37–41 . doi: 10.1016/j.tice.2009.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Connell RM, Rao DS, Chaudhuri AA, Baltimore D (2010) Physiological and pathological roles for microRNAs in the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol 10:111–122 . doi: 10.1038/nri2708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dangwal S, Thum T (2013) MicroRNAs in platelet physiology and pathology: Hämostaseologie 33:17–20 . doi: 10.5482/HAMO-13-01-0002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tüfekci KU, Öner MG, Meuwissen RLJ, Genç Ş (2014) The Role of MicroRNAs in Human Diseases In: Yousef M, Allmer J (eds) miRNomics: MicroRNA Biology and Computational Analysis. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ, pp 33–50 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yuan M, Zhang L, You F, et al. (2017) MiR-145–5p regulates hypoxia-induced inflammatory response and apoptosis in cardiomyocytes by targeting CD40. Mol Cell Biochem. doi: 10.1007/s11010-017-2982-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cui S-Y, Wang R, Chen L-B (2014) MicroRNA-145: a potent tumour suppressor that regulates multiple cellular pathways. J Cell Mol Med 18:1913–1926 . doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raisch J (2013) Role of microRNAs in the immune system, inflammation and cancer. World J Gastroenterol 19:2985 . doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i20.2985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Y, Shi X (2013) MicroRNAs in the regulation of TLR and RIG-I pathways. Cell Mol Immunol 10:65–71 . doi: 10.1038/cmi.2012.55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Torres A, Torres K, Pesci A, et al. (2012) Deregulation of miR-100, miR-99a and miR-199b in tissues and plasma coexists with increased expression of mTOR kinase in endometrioid endometrial carcinoma. BMC Cancer 12: . doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jing L, Hou Y, Wu H, et al. (2015) Transcriptome analysis of mRNA and miRNA in skeletal muscle indicates an important network for differential Residual Feed Intake in pigs. Sci Rep 5:11953 . doi: 10.1038/srep11953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Margolis LM, Rivas DA, Berrone M, et al. (2016) Prolonged Calorie Restriction Downregulates Skeletal Muscle mTORC1 Signaling Independent of Dietary Protein Intake and Associated microRNA Expression. Front Physiol 7: . doi: 10.3389/fphys.2016.00445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palagani A, Op de Beeck K, Naulaerts S, et al. (2014) Ectopic MicroRNA-150–5p Transcription Sensitizes Glucocorticoid Therapy Response in MM1S Multiple Myeloma Cells but Fails to Overcome Hormone Therapy Resistance in MM1R Cells. PLoS ONE 9:e113842 . doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Punga T, Le Panse R, Andersson M, et al. (2014) Circulating miRNAs in myasthenia gravis: miR-150–5p as a new potential biomarker. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 1:49–58 . doi: 10.1002/acn3.24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van der Goten J, Vanhove W, Lemaire K, et al. (2014) Integrated miRNA and mRNA Expression Profiling in Inflamed Colon of Patients with Ulcerative Colitis. PLoS ONE 9:e116117 . doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brogaard L, Heegaard PMH, Larsen LE, et al. (2016) Late regulation of immune genes and microRNAs in circulating leukocytes in a pig model of influenza A (H1N2) infection. Sci Rep 6: . doi: 10.1038/srep21812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee C-H, Kuo W-H, Lin C-C, et al. (2013) MicroRNA-Regulated Protein-Protein Interaction Networks and Their Functions in Breast Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 14:11560–11606 . doi: 10.3390/ijms140611560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou H, Rigoutsos I (2014) MiR-103a-3p targets the 5’ UTR of GPRC5A in pancreatic cells. RNA 20:1431–1439 . doi: 10.1261/rna.045757.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bork-Jensen J, Thuesen A, Bang-Bertelsen C, et al. (2014) Genetic versus Non-Genetic Regulation of miR-103, miR-143 and miR-483–3p Expression in Adipose Tissue and Their Metabolic Implications—A Twin Study. Genes 5:508–517 . doi: 10.3390/genes5030508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McGregor R A, Choi M S (2011) microRNAs in the Regulation of Adipogenesis and Obesity. Curr Mol Med 11:304–316 . doi: 10.2174/156652411795677990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu J, Ji A, Wang X, et al. (2015) MicroRNA-195–5p, a new regulator of Fra-1, suppresses the migration and invasion of prostate cancer cells. J Transl Med 13: . doi: 10.1186/s12967-015-0650-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cai C, Chen Q-B, Han Z-D, et al. (2015) miR-195 Inhibits Tumor Progression by Targeting RPS6KB1 in Human Prostate Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 21:4922–4934 . doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ding J, Huang S, Wang Y, et al. (2013) Genome-wide screening reveals that miR-195 targets the TNF-o/NF-kB pathway by down-regulating IkB kinase alpha and TAB3 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 58:654–666 . doi: 10.1002/hep.26378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smolle E, Haybaeck J (2014) Non-Coding RNAs and Lipid Metabolism. Int J Mol Sci 15:13494–13513 . doi: 10.3390/ijms150813494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fei X, Qi M, Wu B, et al. (2012) MicroRNA-195–5p suppresses glucose uptake and proliferation of human bladder cancer T24 cells by regulating GLUT3 expression. FEBS Lett 586:392–397 . doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang W-M, Jeong H-J, Park S-Y, Lee W (2014) Saturated fatty acid-induced miR-195 impairs insulin signaling and glycogen metabolism in HepG2 cells. FEBS Lett 588:3939–3946 . doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang Q, Xu M, Qu Y, et al. (2015) Analysis of the differential expression of circulating microRNAs during the progression of hepatic fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Mol Med Rep. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.4221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jafarzadeh M, Soltani BM, Dokanehiifard S, et al. (2016) Experimental evidences for hsa-miR-497–5p as a negative regulator of SMAD3 gene expression. Gene 586:216–221 . doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2016.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gheinani AH, Kiss B, Moltzahn F, et al. (2017) Characterization of miRNA-regulated networks, hubs of signaling, and biomarkers in obstruction-induced bladder dysfunction. JCI Insight 2: . doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.89560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ye E-A, Liu L, Jiang Y, et al. (2016) miR-15a/16 reduces retinal leukostasis through decreased pro-inflammatory signaling. J Neuroinflammation 13: . doi: 10.1186/s12974-016-0771-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hou N, Han J, Li J, et al. (2014) MicroRNA Profiling in Human Colon Cancer Cells during 5-Fluorouracil-Induced Autophagy. PLoS ONE 9:e114779 . doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Druz A, Chen Y-C, Guha R, et al. (2013) Large-scale screening identifies a novel microRNA, miR-15a-3p, which induces apoptosis in human cancer cell lines. RNA Biol 10:287–300 . doi: 10.4161/rna.23339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen Z, Qiu H, Ma L, et al. (2016) miR-30e-5p and miR-15a Synergistically Regulate Fatty Acid Metabolism in Goat Mammary Epithelial Cells via LRP6 and YAP1. Int J Mol Sci 17:1909 . doi: 10.3390/ijms17111909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rinnerthaler G, Hackl H, Gampenrieder S, et al. (2016) miR-16–5p Is a Stably-Expressed Housekeeping MicroRNA in Breast Cancer Tissues from Primary Tumors and from Metastatic Sites. Int J Mol Sci 17:156 . doi: 10.3390/ijms17020156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yu A-M, Pan Y-Z (2012) Noncoding microRNAs: small RNAs play a big role in regulation of ADME? Acta Pharm Sin B 2:93–101 . doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2012.02.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang J, Song Y, Zhang C, et al. (2015) Circulating MiR-16–5p and MiR-19b-3p as Two Novel Potential Biomarkers to Indicate Progression of Gastric Cancer. Theranostics 5:733–745 . doi: 10.7150/thno.10305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kishore A, Borucka J, Petrkova J, Petrek M (2014) Novel Insights into miRNA in Lung and Heart Inflammatory Diseases. Mediators Inflamm 2014:1–27 . doi: 10.1155/2014/259131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Prajapati P, Sripada L, Singh K, et al. (2015) TNF-α regulates miRNA targeting mitochondrial complex-I and induces cell death in dopaminergic cells. Biochim Biophys Acta BBA - Mol Basis Dis 1852:451–461 . doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aranda JF, Madrigal-Matute J, Rotllan N, Fernandez-Hernando C (2013) MicroRNA modulation of lipid metabolism and oxidative stress in cardiometabolic diseases. Free Radic Biol Med 64:31–39 . doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.07.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu Z, Wang Y, Borlak J, Tong W (2016) Mechanistically linked serum miRNAs distinguish between drug induced and fatty liver disease of different grades. Sci Rep 6: . doi: 10.1038/srep23709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hatziapostolou M, Polytarchou C, Iliopoulos D (2013) miRNAs link metabolic reprogramming to oncogenesis. Trends Endocrinol Metab 24:361–373 . doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2013.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Guo Z, Gong J, Li Y, et al. (2016) Mucosal MicroRNAs Expression Profiles before and after Exclusive Enteral Nutrition Therapy in Adult Patients with Crohn’s Disease. Nutrients 8:519 . doi: 10.3390/nu8080519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yu H-R, Hsu T-Y, Huang H-C, et al. (2016) Comparison of the Functional microRNA Expression in Immune Cell Subsets of Neonates and Adults. Front Immunol 7: . doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Roessler C, Kuhlmann K, Hellwing C, et al. (2017) Impact of Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids on miRNA Profiles of Monocytes/Macrophages and Endothelial Cells—A Pilot Study. Int J Mol Sci 18:284 . doi: 10.3390/ijms18020284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Blotta MH, Marshall JD, DeKruyff RH, Umetsu DT (1996) Cross-linking of the CD40 ligand on human CD4+ T lymphocytes generates a costimulatory signal that up-regulates IL-4 synthesis. J Immunol Baltim Md 1950 156:3133–3140 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1. NetworkAnalyst evaluation showing the interlinked network of 120 pathways associated with PRKAA1 (AMPK), TREM-1, HIF1α, HMGB1 and AGER (RAGE).

Supplementary Table 2. Nine pathways associated with metabolic homeostasis and inflammation based on AMPK and TREM-1 and their corresponding genes as determined by NetworkAnalyst.

Supplementary Table-3. miRNAs associated with 114 genes from nine pathways associated with metabolic homeostasis and inflammation based on AMPK and TREM-1 from RCTI subjects.

Supplementary Table-4. miRNAs from RCTI patients (FI vs No-FI) having seven or more target genes.