ABSTRACT

The Future Hospital Commission represents a bold and imaginative exploration of some new ways of providing medicine more effectively. It is however, the beginning of a discussion not an endpoint. There are a number of other major changes that will be needed to support the proposals. There will be changes in the role of specialists particularly those involved in chronic disease. Primary and community care will need to become more systematic and consistent and be able to reliably offer a much more extended set of services. There is also a need to look at accident and emergency services and the relationship these have to acute medicine. These new models require development by front line clinicians rather than design by policy makers.

KEYWORDS: : Future Hospital Commission, primary care, emergency medicine, acute medicine

Introduction

Much of the discussion concerning hospital reconfiguration has tended to focus on specialist services, such as surgery, obstetrics and paediatrics. Although it forms the largest part of inpatient activity, medicine has received much less attention and solving the question of how care in this important area should best be provided is key to unlocking change in hospitals.

The report of the Future Hospital Commission (FHC)1 recognises the pressure to redesign care to meet the changing needs of patients. It brings together a number of new principles that have been emerging in the field and combines these in ways that have significant implications for how hospitals and the wider healthcare system should work in future. Specifically, the emphasis on patient experience, as well as strategic ambitions for changes to the wider system and workforce, mean the report has implications for healthcare outside hospitals that are alluded to but not fully worked out. Here I explore the implications for change in other specialties, including primary and community care, that are implied by the FHC's report and that will be needed to make the model work. Bringing these strands together challenges some of the current thinking about the future shape of hospital services.

New roles for specialists

The report presents a welcome assertion of the importance of generalist skills but is also clear about the contribution of specialists. It highlights the need for hospital practitioners to work more closely with primary care and across the boundaries that plague the current system. This proposal is more profound and important than it may at first appear. The traditional model in which patients are referred to a specialist for advice or management has always presented problems. There is established evidence indicating that the understanding of the referrer and the specialist about the job to be done are not always aligned and very often the patient may have a third view of the objectives.2 More fundamentally, the changes that are affecting acute medicine further challenge this traditional model as social complexity, clinical multimorbidity and the need for coordination of care change the way services need to work. As the FHC report notes, patients with chronic conditions need continuity of care that takes into account their social context and co morbidities. It therefore needs to be closely linked to, or at least coordinated by, effective primary care rather than consisting of periodic visits to a specialist determined by the clinic recall schedule rather than clinical need. Patients increasingly require multidisciplinary care, which mandates reliable systems to ensure that treatment plans are carried out – which in turn means there needs to be time to discuss the planned strategy with the patient and/or carer.

The current model of outpatient care does not support this approach, and while emphasis on shifting outpatient care in medical specialties to primary care has increased, it is not clear that primary care has the capacity, time or skills to assume this task. Consequently, redesigning the role of specialists in diabetes, heart failure, cognitive impairment and COPD in particular, together with other ‘ologies’, will be a key part of any effective future model. Indeed, the North London Respiratory service cited in the report is one of a number of models where specialists have started this task. Often this involves devolving some day-to-day management of care back to general practices, but only with support from specialist teams and rapid access to expert assessment, treatment, and management. Longer appointments for the most complex patients, multidisciplinary assessment and case conferences involving social care and other agencies may be required. A change in the approach that specialists take in managing risk is also required; the new models involve sharing this between patients, carers and other healthcare professionals rather than this having to be assumed solely by the specialist. Payment systems, penalties and regulation will have to adapt to this approach.

Thus, consultants will become a key part of a wider network of care, with a key role in overseeing clinical governance, keeping other members of the network up to date and driving learning and improvement.

A consequence of such change is that referral for an outpatient visit may incorporate a wider range of options that include telephone or email consultation, referral to a specialist nurse or other team member, a joint consultation between GP and the specialist team or the patient being seen very rapidly when there is an impending emergency.

In geriatric medicine, specialists are already developing new models of working in the community that are producing impressive results, with some interest among policy makers in very intensive community management of the frail elderly. These so called ‘extensivist’ models focus on those most at risk, targeting at them intensive support, case management and anticipatory care.3 These seem to reduce, at least partially, hospital attendances for this cohort although in general case management approaches have struggled to show a major impact on this endpoint.4

Changes in primary and community care

The FHC report has significant implications for primary and community services that are not fully explored. Fortunately, these are in line with the way in which thinking about these services is developing. If hospital specialists are to be able to work in a more coordinated way with other parts of the system, their services will need to be more consistent in what is offered and easier to comprehend and navigate. Indeed, in many places community services have become complex and fragmented. Large numbers of small, narrowly defined and often poorly coordinated services (often delivered by different providers) have emerged. Often this has been a consequence of services being created for a particular purpose or client group without a clear plan for how they relate to the wider system. This fragmentation leads to patients receiving multiple visits from different professionals, with high costs of coordination and frustration for referring clinicians, carers and patients. Not only is this not necessarily cheaper, but it may also mean that important opportunities to notice changes in the patient's condition can be missed. Care coordinators and navigators, single points of access and other systems can help but in some cases merely create an additional administrative layer without reducing complexity.

The emerging trend is to create more multiskilled teams around localities or groups of general practices, which may include social care staff and mental health support. Some also provide ‘step-up’ services and (early) supported hospital discharge, but these are usually delivered by specialist teams able to respond rapidly, and which develop close relationships with hospital staff. Rapid discharge seems to be most effective when high quality active daily planning in the hospital is combined with ‘pull’ by community services, which together actively identify patients ready for discharge, and this approach will need to become widespread if ambulatory care and rapid return home are to become the default.

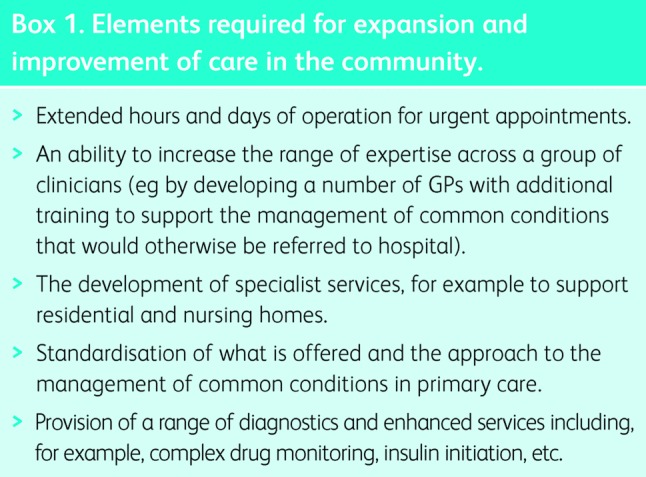

A model of primary care based on small independent practices that also have a high level of variation in what they can offer, their capabilities and levels of expertise is a major barrier to change. Even if there is a change in the willingness of specialists to take more risks, it is not reasonable to expect a patient to be discharged if there is not some confidence in the capability of the clinicians who will be assuming reponsibility for care in the community. There is therefore an emerging consensus that practices need to come together in federations or other larger scale structures. The Royal College of General Practice has been arguing this case5 and there are signs that the combined pressure of rising demand and reduced resources for primary care are tending to promote the development of such a movement.6 While there are economies from combining IT and administrative support, the real advantages for the wider health system are likely to come when practices start to develop a shared approach to the delivery of services. This is likely to include some or all of the elements shown in Box 1.

Box 1. Elements required for expansion and improvement of care in the community.

A recognition that there has been insufficient emphasis on continuity for patients with long term conditions and that more needs to be done to plan care, anticipate needs and help effective self-management is emerging.7 The potential for specialists operating in the new way described by the FHC to support the management of long term conditions in primary care is significant. This could include specialists being members of these ‘super practices’ as well as working at the hospital. All of these changes will require the development of common approaches to the management of common long-term conditions and clarity about where responsibility lies. It will also need shared clinical governance, the ability to share the patient's record and new payment methods referred to in the report.

Creating these larger groups of practices that share a common approach and that are supported by integrated multidisciplinary health and social care teams unlocks the potential of a number of the ideas in the FHC report.

Emergency medicine

Emergency medicine receives less attention in the report than might be expected, given that it is experiencing the same challenges as acute medicine in terms of pressure, staff recruitment and reputation. The report makes a passing reference to the emergency department becoming part of the acute care hub in some cases. Since the FHC reported, Professor Keith Willett has produced the first stage of his report on the future of emergency care which echoes many of the same themes and which suggests significant changes to A&E.8 The models of rapid expert assessment for medical patients advocated in the FHC's report implies that these patients should generally bypass A&E and in general spend as little time there as possible. Taken with the Willett report, this seems to raise questions about the distribution of work and staff between the A&E and acute medical units. For those hospitals not providing major emergency and trauma services, a model in which minor treatment and primary care is provided alongside the acute hub could undertake much of the work currently seen in A&E and improve patient flow and resource utilisation.

Implications

Seven day working and the requirement for a senior opinion to be available over extended periods of the day seem to be driving centralisation of hospital services, and is supported by evidence of improved outcomes associated with higher volumes for some types of care and by Royal College guidance with varying degrees of evidential strength.

Many of the plans for reconfiguration claim to be proposing a radical new model, but in many cases what is put forward is simply a bigger and more centralised version of the current approach. Generally, this is accompanied by plans to reduce admission to hospital and lengths of hospital stay through investment in community services. The evidence to support these is not strong and a more fundamental change to local services may be required.

Although there is further work to do to change the model of care for patients with stroke or acute myocardial infarction, it is not clear that there are major benefits to be had from further centralisation of acute medicine, providing that issues about workforce shortages can be addressed. As the Commission points out, hospital environments are hazardous for many patients and more needs to be done to prevent hospital admission and to minimise length of stay. Ambulatory care, rapid discharge and close ties between specialists and primary and community care are much more difficult where services are provided at a distance.

The proposals in the FHC's report and the other changes associated with it raise the possibility that elements of emergency medicine could be provided more locally, or at the least that there is not a pressing need to centralise acute medicine, saving significant capital costs. Applying population projections to current rates of bed use means that significant increases in efficiency, reductions in length of stay and investment in community services will be required just to absorb these changes.

For example, an assessment unit at Abingdon is able to deal with a significant amount of demand for diagnosis and treatment and has access to point-of-care testing, imaging and comprehensive geriatric assessment. A similar service is being developed elsewhere in Oxfordshire and in Corby. These units may be associated with some step up/down beds to take back patients that do require admission to a major centre once the acute illness has been managed. This seems to require a close relationship with staff who can rotate through the acute centre rather than, as is the case in some places, separate community geriatric services.

Heart of England NHS Trust and Pennine Acute Hospitals NHS Trust both operate acute medical models, with secondary sites being part of a wider local healthcare system. The provision of critical care support is often cited as rate-limiting. Certainly networking appropriate retrieval and transfer arrangements is required for all sites providing acute care. However, opportunities to use remote (monitoring) technology are now emerging for this and other areas where there is an intermittent need for specialist advice, such as a surgical opinion. Previous examples of these models have been difficult to sustain – possibly because they were not sufficiently integrated into the wider network. The third development to complement these trends is the development of interface geriatric models in which a rapid multidisciplinary assessment service is able to pick up patients much earlier and respond rapidly to requests for help. These use a range of community and residential care resources to provide alternative care for patients.

The practicalities of providing high quality emergency care with continuity at a central acute hub while the specialist workforce is increasingly working outside remain to be addressed. In the USA the emergence of generalists (termed hospitalists) has provided part of the solution, but the incentives to develop this role in the same way are not present in the UK.

Combined together these different models offer alternative options to centralisation alone and so could be more cost effective and achievable than the alternative, where the lack of capital and potential for public and political opposition is significant.

Final thoughts

The FHC's report sets out a large number of interesting and important ideas about the future of hospital services. These go well beyond the hospital and have important implications for primary- and community-based care. Obstacles to implementation are correctly identified in the report but the case studies cited show that the most effective changes have been driven by clinicians with a clear vision of how the system needs to change, and who possess or have acquired the skills to redesign and change it themselves.

References

- 1.Royal College of Physicians Hospitals on the edge? The time for action. London: RCP, 2012. Available online at www.rcplondon.ac.uk/sites/default/files/documents/hospitals-on-the-edge-report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coulter A, Roland M. Hospital referrals. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Milstein A, Gilbertson E. American Medical Home Runs. Health Affairs 28:1317–26. 10.1377/hlthaff.28.5.1317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lind S. Risk-profiling DES could increase emergency admissions, says QOF architect. Pulse Today 10 May 2013. Available online at www.pulsetoday.co.uk/home/gp-contract-2014/15/risk-profiling-des-could-increase-emergency-admissions-says-qof-architect/20002812.article. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Royal College of General Practitioners The future direction of general practice: a roadmap. London: RCGP, 2007. Available online at www.rcgp.org.uk/policy/rcgp-policy-areas/∼/media/Files/Policy/A-Z-policy/the_future_direction_rcgp_roadmap.ashx [accessed on 6 January 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith J, Holder H, Edwards N, Rosen R, et al. Securing the Future of General Practice. London: Nuffield Trust, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roland M, Paddison E. Better management of patients with multimorbidity. BMJ 2013;346:f2510. 10.1136/bmj.f2510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.NHS England Transforming urgent and emergency care services in England. End of phase I report. London: NHS England, 2013. Available online at www.nhs.uk/NHSEngland/keogh-review/Documents/UECR.Ph1Report.FV.pdf [accessed on 6 January 2014]. [Google Scholar]