Abstract

Purpose

To develop and test an artificial intelligence (AI) system, based on deep convolutional neural networks (CNNs), for automated real-time triaging of adult chest radiographs on the basis of the urgency of imaging appearances.

Materials and Methods

An AI system was developed by using 470 388 fully anonymized institutional adult chest radiographs acquired from 2007 to 2017. The free-text radiology reports were preprocessed by using an in-house natural language processing (NLP) system modeling radiologic language. The NLP system analyzed the free-text report to prioritize each radiograph as critical, urgent, nonurgent, or normal. An AI system for computer vision using an ensemble of two deep CNNs was then trained by using labeled radiographs to predict the clinical priority from radiologic appearances only. The system’s performance in radiograph prioritization was tested in a simulation by using an independent set of 15 887 radiographs. Prediction performance was assessed with the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) were also determined. Nonparametric testing of the improvement in time to final report was determined at a nominal significance level of 5%.

Results

Normal chest radiographs were detected by our AI system with a sensitivity of 71%, specificity of 95%, PPV of 73%, and NPV of 94%. The average reporting delay was reduced from 11.2 to 2.7 days for critical imaging findings (P < .001) and from 7.6 to 4.1 days for urgent imaging findings (P < .001) in the simulation compared with historical data.

Conclusion

Automated real-time triaging of adult chest radiographs with use of an artificial intelligence system is feasible, with clinically acceptable performance.

© RSNA, 2019

Online supplemental material is available for this article.

See also the editorial by Auffermann in this issue.

Summary

An artificial intelligence system, developed on a data set of 470 388 adult chest radiographs, is able to interpret and prioritize abnormal radiographs with critical or urgent findings.

Implications for Patient Care

■ Our artificial intelligence (AI)–based system detected abnormal from normal adult chest radiographs with a high positive predictive value of 94%.

■ This AI system can be used to triage radiographs for reporting.

■ Our simulations show abnormal radiographs with critical findings receive an expert radiologist opinion sooner (2.7 vs 11.2 days on average) with use of AI prioritization compared with our actual practice.

Introduction

The application of deep neural networks to medical imaging is an evolving research field (1,2). An artificial neural network consists of a set of simple processing units, artificial neurons, connected in a network, organized in layers, and trained with a backpropagation algorithm (3). The resulting computational model is able to learn representations of data with a high level of abstraction (4).

Deep neural networks have been shown to achieve excellent performance on many natural computer vision tasks, which is advantageous for medical specialties such as radiology and dermatology (4,5). Previous work has indicated that the performance of deep learning algorithms is comparable to or even exceeds the performance of radiologists in detecting consolidation on chest radiographs (6), segmenting cysts in polycystic kidney disease on CT scans (7), and detecting pulmonary nodules on CT scans (8).

Artificial intelligence (AI)–led independent reporting of imaging remains a controversial topic; however, many radiologists would agree that deep learning technology could be a valuable tool in improving workflow and workforce efficiency (9–11). The increasing clinical demands on radiology departments worldwide have challenged current service delivery models, particularly in publicly funded health care systems. In some settings, it may not be feasible to report all acquired radiographs in a timely manner, leading to large backlogs of unreported studies (12,13). For example, the United Kingdom estimates that, at any time, 330 000 patients are waiting more than 30 days for their reports (14). Therefore, alternative models of care should be explored, particularly for chest radiographs, which account for 40% of all diagnostic images worldwide (15).

Better mechanisms for triaging abnormal versus normal chest radiographs and prioritization of abnormal radiographs (eg, according to the “criticality” of the findings) for reporting are key to improving workflow. We hypothesized that an AI-based system, powered by deep learning algorithms for computer vision, might be able to identify key findings on chest radiographs. With use of this information, real-time prioritization of abnormal radiographs for reporting, based on the criticality of findings, may be possible within current picture archiving and communication systems. Therefore, we aimed to develop and test an AI system, based on deep convolutional neural networks (CNNs), for automated real-time triaging of adult chest radiographs on the basis of the urgency of imaging appearances.

Materials and Methods

The institutional review board waived the requirement to obtain informed consent for our retrospective study, which used fully anonymized reports and radiographs.

Data Set

A total of 832 265 frontal chest radiographs were obtained from January 2005 to May 2017 at our institution, a publicly funded university hospital network consisting of three hospitals. All 832 265 radiograph reports in digital format from our radiology information system were included for natural language processing (NLP). Of the 832 265 original resolution chest radiographs acquired since picture archiving and communication system implementation in 2007, 677 030 (81.3%) were available in Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine format. Pediatric radiographs (obtained in patients <16 years, 206 642 of 677 030 radiographs [30.5%]) were excluded, leaving a final data set of 470 388 (69.5%) consecutive adult chest radiographs for deep learning with no further exclusions. The 413 403 consecutive radiographs acquired before April 1, 2016, were separated into training (n = 329 698, 79.7%), testing (n = 41 407, 10%), and internal validation (n = 42 298, 10.2%) sets, ensuring that the distribution of age and abnormalities within each subset matched the entire data set. Radiographs obtained after April 1, 2016, were used to assess the prioritization system performance in a simulation study. Figure 1 summarizes this.

Figure 1:

Flowchart shows different data sets used for training, learning, and testing. Approximately 8% of radiographs were critical, 40% urgent, 26% nonurgent, and 26% normal across the training, test, and validation data sets.

NLP-generated Radiograph Annotation and Labeling

Annotation of the radiographs was automated by developing an NLP system that was able to process and map the language used in each radiology report (16). The architecture of our NLP system was somewhat similar to the architecture described by Cornegruta et al (17) and Pesce et al (18). Figure 2 shows an example of how terminology (“entities”) including negation attributes and interrelationships was extracted from the radiology report and processed by a rule-based system, producing a list of confirmed findings. These were then mapped onto 15 radiologic “labels” (Table 1). These labels reflected the most common and clinically important radiographic findings within our data set. These were then mapped onto four clinical prioritization levels selected to reflect our current reporting practice, as follows: (a) critical, requiring an immediate report due to a clinically critical finding (eg, pneumothorax); (b) urgent, requiring a report within 48 hours due to a clinically important but not critical finding (eg, consolidation); (c) nonurgent, requiring a report within the standard departmental turnaround time due to nonclinically important findings (eg, hiatus hernia); and (d) normal (ie, no abnormalities on radiograph) (Table 1). A reference standard data set was initially generated for testing purposes by randomly extracting 4551 chest radiographs from the whole data set. The labels in this data set were manually validated by two radiologists-in-training (S.J.W., R.J.B., with 3 years of experience) independently, with any disagreements resolved in consensus with staff radiologist review (>10 years of experience).

Figure 2:

Example of radiologic report annotated by natural language processing system. “Entities” are highlighted with different colors, one for each semantic class. Arrows represent relationships between entities. Final annotation extracted by the rule-based system was “airspace opacification; pleural effusion/abnormality.”

Table 1:

List of Selected Radiologic Labels and Corresponding Priority Levels

Note.—An additional “normal” label was used for radiographs with no abnormalities.

Deep Learning Architecture for Criticality Prediction from Image Data

The computer vision system was implemented on the basis of ordinal regression models, making use of two deep CNNs for the automatic extraction of imaging patterns directly from pixel values. All 329 698 images in the training set were used for end-to-end training of the convolutional networks (Appendix E1 [online]). A reduced reference standard data set was generated for testing purposes by randomly sampling a subset of 3299 examinations (72.5%) from the 4551 examinations contained in the reference standard data set.

Automated Image Prioritization: Simulation Study

The computer vision algorithms were used to build an automated radiograph prioritization system, as illustrated in Figure 3. The system operates in real time: When a radiograph is acquired, it is processed by the deep CNN and assigned a predicted priority level. It is then inserted into a “dynamic reporting queue” on the basis of its predicted urgency and the waiting time of other already queued radiographs. To quantify the potential benefits that can be achieved by our AI system in a real clinical setting, a simulation study was performed on data collected after April 1, 2016. We simulated what would have happened if our AI system was used to order radiographs for reporting. To introduce a level of “clinical” realism, we also generated “noisy" versions of the queuing process. Each examination had a small, fixed probability (either 0.1 or 0.2) of not being reported according to our automated queuing system, that is, the original reporting time stamp was left unchanged. This was to mimic a clinical scenario where radiographs would be reported out of order, for example, at the request of a referrer or due to chance (Appendix E1 [online]). The Python code (version 1.0) implementing the deep CNN and simulation algorithms can be found online at: https://github.com/WMGDataScience/chest_xrays_triaging.

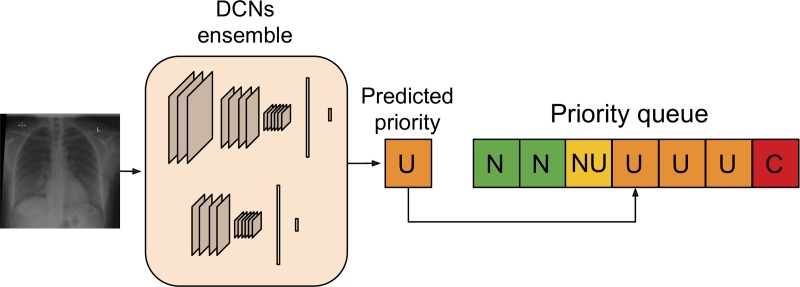

Figure 3:

Artificial intelligence prioritization system: When a chest radiograph is acquired, the deep learning architecture (consisting of two different deep convolutional neural networks [DCNs] operating at different input sizes) processes the image in real time and predicts its priority level (eg, urgent, in this example). Given the predicted priority, the image is then automatically inserted in a dynamic priority-based reporting queue. C = critical, N = normal, NU = nonurgent, U = urgent.

Statistical Analysis

The predictive performance of the NLP and AI system was assessed by using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and F1 score (a measure of accuracy, reflecting the harmonic mean of PPV and sensitivity, where 1 represents perfect PPV and sensitivity) were determined. To assess the effect of the prioritization system on reporting delay (time from acquisition to final report completion) in the simulation study, a nonparametric, randomization-based statistical test was performed. A null distribution for the average reporting delay within each priority class was obtained by running the prioritization process 500 000 times under the null hypothesis that all four classes are prioritized in the same way. Hence, in each run, a priority class was assigned to each radiograph at random, unrelated to the image, with equal probability of each class. The statistical significance of the prioritization results was assessed by comparing the observed values against the null distribution. Significance was at the 5% level.

Results

NLP-generated Radiograph Annotation and Labeling

Table 2 summarizes the performance of the NLP system, assessed on the standard of reference data set. NLP performance was very good, achieving a sensitivity of 98%, specificity of 99%, PPV of 97%, and NPV of 99% for normal radiographs and a sensitivity of 96%, specificity of 97%, PPV of 84%, and NPV of 99% for critical radiographs. The NLP system was able to extract the presence or absence of almost all the radiologic findings within the free-text reports with a high degree of accuracy (F1 score, 0.81–0.99) (Appendix E1 [online]). The most challenging label was “parenchymal lesion,” which had the lowest accuracy. This was likely related to the ambiguity of language used within the reports; varying terminology, including “shadow” and “opacity,” was used when alluding to a possible cancer. Other categories, for example, “pleural effusion” and “cardiomegaly,” were referred to far more specifically in the text and, consequently, resulted in a better NLP performance (F1 score, 0.94 and 0.99, respectively) (Appendix E1 [online]).

Table 2:

Performance of the Natural Language Processing System

Note.—Performance was evaluated with use of the reference standard data set. Rows represent the ground truth and columns represent prediction. NPV = negative predictive value, PPV = positive predictive value.

Deep Learning Architecture for Criticality Prediction from Image Data

Table 3 summarizes the performance of the AI prioritization system, assessed on the standard of reference data set. AI performance was good, with a sensitivity of 71%, specificity of 95%, PPV of 73%, and NPV of 94% for normal radiographs (Fig 4) and a sensitivity of 65%, specificity of 94%, PPV of 61%, and NPV of 95% for critical radiographs. Of note, five of the 385 “critical” radiographs (1%) were labeled as normal. On rereview of these five critical radiographs, the AI interpretation of normal was unanimously believed to be correct in four of five instances. Figure 5 illustrates some cases in which the AI system made correct and incorrect predictions.

Table 3:

Performance of the Artificial Intelligence System for Examination Prioritization

Note.—Prioritization was implemented as an ordinal classifier assessed on the reference standard data set. Rows represent ground truth, columns represent prediction. NPV = negative predictive value, PPV = positive predictive value.

Figure 4:

Receiver operating characteristic curve for normality prediction obtained by the artificial intelligence system. The system achieved an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC ) of 0.94.

Figure 5a:

Examples of correctly and incorrectly prioritized radiographs. (a) Radiograph was reported as showing large right pleural effusion (arrow). This was correctly prioritized as urgent. (b) Radiograph reported as showing “lucency at the left apex suspicious for pneumothorax.” This was prioritized as normal. On review by three independent radiologists, the radiograph was unanimously considered to be normal. (c) Radiograph reported as showing consolidation projected behind heart (arrow). The finding was missed by the artificial intelligence system, and the study was incorrectly prioritized as normal.

Figure 5b:

Examples of correctly and incorrectly prioritized radiographs. (a) Radiograph was reported as showing large right pleural effusion (arrow). This was correctly prioritized as urgent. (b) Radiograph reported as showing “lucency at the left apex suspicious for pneumothorax.” This was prioritized as normal. On review by three independent radiologists, the radiograph was unanimously considered to be normal. (c) Radiograph reported as showing consolidation projected behind heart (arrow). The finding was missed by the artificial intelligence system, and the study was incorrectly prioritized as normal.

Figure 5c:

Examples of correctly and incorrectly prioritized radiographs. (a) Radiograph was reported as showing large right pleural effusion (arrow). This was correctly prioritized as urgent. (b) Radiograph reported as showing “lucency at the left apex suspicious for pneumothorax.” This was prioritized as normal. On review by three independent radiologists, the radiograph was unanimously considered to be normal. (c) Radiograph reported as showing consolidation projected behind heart (arrow). The finding was missed by the artificial intelligence system, and the study was incorrectly prioritized as normal.

Automated Image Prioritization: Simulation Study

Table 4 presents the results of our simulation study for our triaging system and the original observed historical data. Our AI triaging system substantially reduced the mean (± standard deviation) delays for the examinations reported as critical, from 11.2 days ± 17.84 to 2.7 days ± 11.88; the median delay was reduced from 7.2 hours to 43 minutes (Appendix E1 [online], Fig 6). Even in the simulations with additional noise, to simulate some radiographs being reported out of order, it was still possible to see the benefits of our proposed triaging system. We were still able to greatly reduce the average “time to report” for critical and urgent examinations: 85% of the examinations labeled as critical would have been reported within the first day with our system, compared with 60% of the critical examinations reported from the historical data. As expected, the time to report for normal examinations introduced by the AI system also changed and would have been longer.

Table 4:

Effect of Triaging

Note.—Except where indicated, data are mean reporting delays ± standard deviations. Reporting delay is the time from acquisition to final report, in days. Simulated 0.1 noise and Simulated 0.2 noise are simulations with 10% or 20% of radiographs being reported out of order (ie, lower-priority radiographs were reported sooner due to clinician request or an upcoming appointment).

*Improvement was calculated by dividing historical mean delay by the simulated mean delay.

Figure 6:

Mean reporting time from acquisition with artificial intelligence (AI) prioritization system compared with observed mean for critical radiographs. P values were obtained nonparametrically by using a null distribution (shown here), that is, a distribution of mean reporting time obtained under null hypothesis that order in which examinations are reported is not dependent on criticality class. The null distribution is generated by simulating 500 000 realizations of a randomized prioritization process, that is, the priority class in each realization is randomly assigned irrespective of image content.

Discussion

Our NLP system was able to extract out the presence or absence of radiologic findings within the free-text reports with a high degree of accuracy, as demonstrated by an F1 score of 0.81–0.99. It was also able to assign a priority level with a sensitivity of greater than 90% and specificity of greater than 96%, as assessed with the reference standard data set. Similarly, our deep CNN–based computer vision system was able to separate normal from abnormal chest radiographs with a sensitivity of 71%, specificity of 95%, and NPV of 94%. In assigning a priority level, performance was lower, with a sensitivity of more than 65% and a specificity of more than 76% for critical and urgent radiographs, respectively. In terms of misclassifications, of the 545 radiographs classified as normal by our AI system, five (1%) had critical and 95 (17%) had urgent findings detailed within the reports. On rereview of these five critical radiographs, the AI interpretation of normal was unanimously believed to be correct in four instances. Similarly, for the 95 urgent radiographs, 36 (38%) were normal on rereview.

Previously published studies have investigated the potential of NLP and computer vision techniques in the classification of radiographs (6,19,20) but not for real-time prioritization, which was our primary aim. One simple study was able to classify chest radiographs as either frontal or lateral projections with high fidelity (100% correctly classified) (19). Another study classifying chest radiographs as normal or as showing cardiomegaly, consolidation, pleural effusion, pulmonary edema, or pneumothorax found a sensitivity and specificity of 91% for normal radiographs (20). However, anteroposterior radiographs were excluded, and it should be stressed that any radiograph with “minor” findings outside of the five abnormalities were considered as normal—a clear limitation (20). Another study of the detection of pneumonia found that the performance of the CheXNet algorithm (6), which was tested against four radiologists by using consensus as the ground truth, was substantially better, with an F1 score of 0.435 for the AI system. However, F1 scores remained low (6). The performance of our AI system surpassed the performance in these studies, but further work is required to improve the misclassification rate.

In our study, we observed that averaging the predictions from two different CNNs operating at two different spatial resolutions yielded the best performance. One reason for this may be that the two networks are complementary, that is, the Inception v3 network, acting on smaller images—which have lower complexity—is able to better recognize abnormal patterns that are still visible at a low resolution, whereas the network operating on the 1211 × 1083 images is better suited to detecting visual patterns that are otherwise missed at a lower resolution. Further work will be directed toward developing a multiresolution architecture whereby the optimal image sizes are automatically selected.

In our simulation using real historical data, our prioritization system had a positive effect on reporting turnaround times, even in simulations where 10% or 20% of radiographs would be reported out of order; most critical radiographs would have been reported within 24 hours of acquisition irrespective of referrer or clinical information. However, mean delays remained at 2.7 and 4.1 days for critical and urgent radiographs, respectively, which would remain unacceptable for North American practice. We would also have increased reporting turnaround times for normal radiographs, with less than 40% of examinations being reported within 24 hours with our proposed AI system. These results belie the variance of reporting turnaround times of our historical data set and, more important, highlight that our organizational behaviors and clinical pathways have a substantial effect on reporting turnaround (eg, when in the 24-hour day the chest radiographs were requested, which department and/or referrer they came from, and the radiology staffing levels for reporting radiographs at different times of the day, week, or month within our hospital network). These must be taken into account in future prospective work in the field.

Our study had some limitations. First, our current system still has a potential clinical risk from delayed reporting of cases falsely classified as normal, although reassuringly, the false-negative rate was low in our study. Nevertheless, further work is required to reduce this likelihood to a minimum. Second, each radiologic label reflects a spectrum of pathologic characteristics. For example, “collapse” ranges from segmental atelectasis to full lobar collapse, with very different levels of urgency in their management. Third, as imaging findings have been grouped into prioritization categories, the performance of the AI system could appear exaggerated; for example, some studies may be added to the correct priority class but for the wrong reasons. Fourth, our prioritization system can only take into account findings from a single image that is viewed in isolation and without its clinical context. For example, in a patient with lobar consolidation, if the request form states they are already being treated with antibiotics, this becomes much less urgent as clinical management will not necessarily change. Fifth, error is inherent in radiology, due to perception, cognitive, or even typographical errors. Over such a large data set, approximately 3%–5% of labels extracted can be expected to contain an error (21). Sixth, we excluded in-patient radiographs in our simulation because our institutional practice is to report these nonurgently, weeks to months after acquisition, primarily to exclude other nonacute diagnoses. If these patients were incorporated into our simulation, these radiographs would have given the erroneous impression that patients with critical radiographs were being treated with little radiologic input and would have falsely overstated the benefits of our algorithm. Finally, a modeling assumption is that all radiographs take the same amount of time to report; this may not be the case.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated the feasibility of AI for triaging chest radiographs. Our deep learning system developed on our institutional data set of 470 388 adult chest radiographs was able to interpret and prioritize chest radiographs such that abnormal radiographs with critical or urgent findings could be queued for real-time reporting and completed sooner than with our current system. This is promising for future clinical implementation.

APPENDIX

SUPPLEMENTAL FIGURES

Supported by the King’s Health Partners’ Research and Development Challenge Fund, a King’s Health Accelerator Award, the Department of Health via the National Institute for Health Research Comprehensive Biomedical Research Centre Award to Guy's & St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust in partnership with King's College London and King's College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, the King's College London/University College London Comprehensive Cancer Imaging Centre funded by Cancer Research UK and Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) in association with the Medical Research Council and Department of Health (C1519/A16463), and Wellcome EPSRC Centre for Medical Engineering at King’s College London (WT 203148/Z/16/Z).

M.A. and S.J.W. contributed equally to this work.

Disclosures of Conflicts of Interest: M.A. disclosed no relevant relationships. S.J.W. disclosed no relevant relationships. R.J.B. disclosed no relevant relationships. E.P. disclosed no relevant relationships. V.G. Activities related to the present article: disclosed no relevant relationships. Activities not related to the present article: received payment for lectures including service on speakers bureaus from Siemens Healthineers. Other relationships: disclosed no relevant relationships. G.M. disclosed no relevant relationships.

Abbreviations:

- AI

- artificial intelligence

- CNN

- convolutional neural network

- NLP

- natural language processing

- NPV

- negative predictive value

- PPV

- positive predictive value

References

- 1.Geras KJ, Wolfson S, Kim SG, Moy L, Cho K. High-resolution breast cancer screening with multi-view deep convolutional neural networks. Cornell University Library; https://arxiv.org/abs/1703.07047. Published June 28, 2018. Accessed August 15, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lakhani P, Sundaram B. Deep learning at chest radiography: automated classification of pulmonary tuberculosis by using convolutional neural networks. Radiology 2017;284(2):574–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rumelhart DE, Hinton GE, Williams RJ. Learning representations by back- propagating errors. Nature 1986;323(6088):533–536. [Google Scholar]

- 4.LeCun Y, Bengio Y, Hinton G. Deep learning. Nature 2015;521(7553):436–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Esteva A, Kuprel B, Novoa RA, et al. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature 2017;542(7639):115–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rajpurkar P, Irvin J, Zhu K, et al. CheXNet: radiologist-level pneumonia detection on chest x-rays with deep learning. Cornell University Library; https://arxiv.org/abs/1711.05225. Published December 25, 2017. Accessed May 3, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kline TL, Korfiatis P, Edwards ME, et al. Performance of an artificial multi-observer deep neural network for fully automated segmentation of polycystic kidneys. J Digit Imaging 2017;30(4):442–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ciompi F, Chung K, van Riel SJ, et al. Towards automatic pulmonary nodule management in lung cancer screening with deep learning. Sci Rep 2017;7(1):46479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Recht M, Bryan RN. Artificial intelligence: threat or boon to radiologists? J Am Coll Radiol 2017;14(11):1476–1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thrall JH, Li X, Li Q, et al. Artificial intelligence and machine learning in radiology: opportunities, challenges, pitfalls, and criteria for success. J Am Coll Radiol 2018;15(3 Pt B):504–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siemens. Medical imaging in the age of artificial intelligence . https://www.siemens.com/press/pool/de/events/2017/healthineers/2017-11-rsna/white-paper-medical-imaging-in-the-age-of-artificial-intelligence.pdf. Published 2017. Accessed June 19, 2018.

- 12.Royal College of Radiologists . Clinical radiology UK workforce census 2016 report. Contract no.: BFCR(17)6. London, England: Royal College of Radiologists, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clinical Excellence Commission . Final report: recommendations of the Clinical Advisory Committee—plain x-ray image reporting backlog. Sydney, Australia: Clinical Excellence Committee, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Royal College of Radiologists . Unreported x-rays, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans: results of a snapshot survey of English National Health Service (NHS) trusts. London, England: Royal College of Radiologists, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization . Scientific background. In: Communicating radiation risks in paediatric imaging: information to support healthcare discussions about benefit and risk. http://www.who.int/ionizing_radiation/pub_meet/radiation-risks-paediatric-imaging/en/. Published 2016. Accessed December 28, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zech J, Pain M, Titano J, et al. Natural language-based machine learning models for the annotation of clinical radiology reports. Radiology 2018;287(2):570–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cornegruta S, Bakewell R, Withey S, Montana G. Modelling radiological language with bidirectional long short-term memory networks. Cornell University Library. https://arxiv.org/abs/1609.08409. Accessed May 20, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pesce E, Ypsilantis PP, Withey S, Bakewell R, Goh V, Montana G. Learning to detect chest radiographs containing lung nodules using visual attention networks. Cornell University Library. https://arxiv.org/abs/1712.00996. Accessed May 20, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rajkomar A, Lingam S, Taylor AG, Blum M, Mongan J. High-throughput classification of radiographs using deep convolutional neural networks. J Digit Imaging 2017;30(1):95–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cicero M, Bilbily A, Colak E, et al. Training and validating a deep convolutional neural network for computer-aided detection and classification of abnormalities on frontal chest radiographs. Invest Radiol 2017;52(5):281–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee CS, Nagy PG, Weaver SJ, Newman-Toker DE. Cognitive and system factors contributing to diagnostic errors in radiology. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2013;201(3): 611–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.