Abstract

Adrenal androgens dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and DHEA-sulfate (DHEAS) are potential substrates for intracrine production of testosterone (T) and dihydrotestosterone (DHT), or directly to DHT, by prostate cancer (PCa) cells. Production of DHT from DHEAS and DHEA, and the role of steroid sulfatase (STS), were evaluated ex vivo using fresh human prostate tissue and in vitro using human PCa cell lines. STS was expressed in benign prostate tissue and PCa tissue. DHEAS at a physiological concentration was converted to DHT in prostate tissue and PCa cell lines, which was STS-dependent. DHEAS activation of androgen receptor (AR) and stimulation of PCa cell growth were STS-dependent. DHEA at a physiological concentration was not converted to DHT ex vivo and in vitro, but stimulated in vivo tumor growth of the human PCa cell line, VCaP, in castrated mice. The findings suggest that targeting metabolism of DHEAS and DHEA may enhance androgen deprivation therapy.

Introduction

Prostate cancer is the second most common cancer in human males and is the second leading cause of cancer-related death in American males. Androgen receptor (AR)-mediated gene transcription in the target tissue is critical to the proliferation and progression of PCa (Dai et al., 2017,Stuchbery et al., 2017,Mohler, 2008), with the circulating testicular androgens testosterone (T) and dihydrotestosterone (DHT) as the preferred AR-activating ligands (Wilson and French, 1976). Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), whether medical or surgical, is used to reduce the levels of circulating T and DHT, and inhibit AR-mediated gene expression in the target organ, and has represented the standard-of-care for treatment of locally advanced and metastatic PCa for over seventy years. Patients treated with ADT respond well initially, however, the majority of PCas treated with ADT progress to castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC). CRPC is the lethal form of PCa, and currently there is no effective therapy to treat CRPC.

Mounting evidence indicates that T and DHT production in PCa cells, also called intracrine steroidogenesis, is a/the mechanism for resistance of CRPC to ADT (Dai et al., 2017,Stuchbery et al., 2017). PCa cells may acquire the ability to utilize cholesterol, androgenic metabolites of cholesterol, or precursors to androgenic steroids as substrates for local production of T and/or DHT, and therefore, bypass the requirement for circulating T and DHT for maintaining AR activity. Mechanisms proposed for intra-tumoral intracrine steroidogenesis include: the front-door pathway, which uses DHEA and androstenedione (A4) as precursors to generate T that is further reduced to DHT by 5α-reductase (SRD5A)-1, -2, or -3; the back-door pathway, which is initiated by the SRD5A1 reduction of 17-hydroxyprogesterone to produce DHT through sequential intermediates androstenediol and androstanediol and therefore without T as an intermediate (Kamrath et al., 2012a,Kamrath et al., 2012b); and the second back-door pathway, which also metabolizes progesterone to produce DHT without T as an intermediate but with androstanedione as an intermidiate (Stuchbery et al., 2017,Mohler et al., 2011,Mostaghel, 2013,Fiandalo et al., 2014). Another pathway that converts A4 to produce 11-ketotestosterone (11KT) and 11-kto-5<alpha>-dihydrotestosterone (11KD) (Pretorius et al., 2016,Storbeck et al., 2013,Pretorius et al., 2017) has emerged recently as a potentially important androgen metabolism pathway. In this newly established pathway, A4 is hydroxylated by cytochrome P450 11β-hydroxylase (CYP11B1) to 11β-hydroxyandrostenedione (11OH-A4), which is further metabolized to 11KT and 11KDHT. Since 11KT and 11KDHT were found to be potent AR agonists (Pretorius et al., 2016,Storbeck et al., 2013,Bloem et al., 2015), DHEAS, DHEA and A4 may contribute to the production of AR-stimulatory androgens in addition to T and DHT. The actual implementation of these pathways would depend on the expression of key enzymes in tumor tissue, the presence of the requisite substrates and co-factors, whether production of DHT can bypass T as an intermediate, and the changes in expression of enzymes and in the concentrations of substrates/co-factors in response to the specific type of ADT. Potential proximal precursors for intracrine production of T and DHT in humans and other primates include dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and DHEA-sulfate (DHEAS) that are produced in the adrenal glands (Rainey et al., 2002). DHEAS is the predominant adrenal androgen, and the most abundant androgen in the circulation. Levels of circulating DHEAS and DHEA are in the range of 3.5 μM and 10 nM, respectively (Travis et al., 2007,Wurzel et al., 2007,Ryan et al., 2007). Further, the concentrations of DHEAS and DHEA remain in the μM and nM ranges after ADT (Snaterse et al., 2017). DHEA is metabolized to androstenedione (and further to androstanedione), or to androstenediol, all of which can be converted in a single step to T or DHT as part of the front door androgen metabolism pathway (Stuchbery et al., 2017,Fiandalo et al., 2014). The adrenal gland also produce other C19 steroids in addition to DHEAS, DHEA, and A4, such as 11OH-A4, which is produced in adrenal gland at substantial amount and exists in the serum in nM range (Rege et al., 2013,du Toit et al., 2017). Therefore, the involvement of C19 adrenal steroids in intra-tumoral production of AR-stimulatory androgens are not limited to the more traditional DHEAS and DHEA to T and/or DHT conversion.

DHEAS is hydrolyzed to DHEA by arylsulfatase C (steroid sulfatase, STS) within target cells, providing the substrate for intracrine synthesis of T and DHT (Nussbaumer and Billich, 2004,Purohit and Foster, 2012,Reed et al., 2005). There are 12 different sulfatases in humans, however, STS is the only sulfatase that hydrolyzes steroid sulfates (Nussbaumer and Billich, 2004). STS is expressed in benign and malignant prostate tissues, therefore, both benign and cancer tissue can convert DHEAS to DHEA (Nakamura et al., 2006,Klein et al., 1988,Klein et al., 1988,Voigt and Bartsch, 1986,Farnsworth, 1973,Cowan et al., 1977,Klein et al., 1989).

Intracrine production of DHT from DHEA as the sole androgenic precursor has been investigated in fresh PCa tissue specimens and in PCa cell line models (Fankhauser et al., 2014,Chang et al., 2013,Hettel et al., 2018). These studies utilized concentrations of DHEA in a range of sub-nM to 100 nM, and found that DHEA either was, or was not, a substrate for DHT production depending on the concentration used. It is possible that conversion of the more abundant DHEAS to DHEA may provide intra-cellular concentrations of DHEA sufficient to drive DHT production. Consequently, DHEAS must be considered as a ubiquitously present potential substrate for T and DHT production after ADT due to its high abundance. However, the contribution of DHEAS to intracrine T and DHT production in CRPC cells is unknown. The uptake mechanism for DHEA to enter cancer cells is not clear, whereas, DHEAS is a known substrate for multiple uptake transporters including the solute carrier organic anion (SLCO) transporters (Roth et al., 2012,Obaidat et al., 2012,Cho et al., 2014). In addition, the expression in both prostate epithelial and PCa cells of STS that is required to mediate conversion of DHEAS to DHEA would support the potential of PCa cells to metabolize DHEAS. Therefore, it is essential that the role of DHEAS in intracrine T and DHT production be clarified, particularly in the post-ADT environment.

In the present study, fresh clinical specimens of prostate tissue, human PCa cell lines and xenograft models of a human PCa were used to investigate the ability of prostate tissue and PCa cells to utilize adrenal androgens as substrates for DHT production, to activate AR, and to support cancer cell growth. Our findings indicate the clinical importance of therapeutically targeting metabolism of adrenal androgens, particularly DHEAS, in addition to targeting metabolism of testicular androgens, achieve complete ADT by preventing rescue of T deprivation by endogenous DHEA/S.

Materials and Methods

Reagents, cell lines, matched benign and malignant prostate RNA samples, fresh clinical prostate tissue specimens procured, and prostate tissue microarray (TMA)

T, DHEA, and DHEAS were purchased from Steraloids (Newport, RI). Stock solution of the androgens were prepared in ethanol. The STS inhibitor STX64 was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. STX64 stock solution was prepared in DMSO. All stock solutions were diluted 1:1000 (v/v) in tissue culture medium for treatments.

Human PCa cell lines VCaP, LNCaP, and 22Rv1 were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) (Manassas, VA). The human PCa cell line LAPC-4 was established in the laboratory of Dr. Charles Sawyers (Klein et al., 1997). The human PCa cell line C4-2, derived from LNCaP by Leland Chung (Wu et al., 1994), was purchased from MD Anderson Cancer Center (Houston, TX). VCaP and LAPC-4 cells express wild-type AR; LNCaP and LNCaP derivative C4-2 cells express a mutant AR (T877A); and 22Rv1 cells express a mutant AR (H874Y) (Sobel and Sadar, 2005,Sobel and Sadar, 2005).

A total of 20 matched pairs of RNA samples from PCa tissue and adjacent benign prostate tissue from individual patients, were obtained from the Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center (RPCCC) Pathology Network Shared Resources (PNSR), with approval by the institutional review board (IRB).

Fresh remnant prostate tissue specimens were received from PNSR at RPCCC, with approval by the IRB.

A TMA block was constructed by the RPCCC PNRS using formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue specimens. The TMA block contained matched PCa tissue and adjacent benign prostate tissue from 10 patients. Each tissue specimen had 3 cores. Serial sections (thickness 4 μm) from the TMA block were prepared by PNSR at RPCCC. The use of the TMA was covered under an institutional comprehensive tissue procurement protocol “Roswell Park Remnant Clinical Biospecimen Storage, Collection and Distribution for Research Purposes”.

Cell culture conditions

VCaP cells were maintained in DMEM medium (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). All other cell lines were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (ThermoFisher Scientific). For LAPC-4 cells, tissue culture vessels were coated with 1.7 μg/mL poly-D-lysine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in H2O at 0.076 mL/cm2, at room temperature for 15 min, followed by aspiration of the coating reagent and overnight air dry. All media preparations contained 2mM L-glutamine (Corning Life Sciences, Tewksbury, MA), 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Corning Life Sciences). Medium was supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Atlantic Biologicals, Atlanta, GA) for cell culture maintenance, or with 10% charcoal-stripped FBS (CS-FBS) for treatment. CS-FBS was prepared from FBS using filtration through activated charcoal, as described (Fiandalo et al., 2018). For experiments set up in 24-well plates, VCaP was seeded at 75,000 cells/well, while other cell lines were seeded at 50,000 cells/per well in 0.5 mL medium and cultured for 7 and 3 days, respectively. For experiments set up in 6-well plates, cell lines were seeded at 3 × 105 cells/well, 2 mL medium and cultured for 7 and 3 days for VCaP and other cell lines, respectively. Cells were cultured in phenol red-free versions of each medium supplemented with 10% CS-FBS for 1 day before treatment, and treated in freshly prepared phenol red-free medium supplemented with 10% CS-FBS. Cells were incubated at 37° C, in an atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2.

Cell viability/proliferation assays

Cell viability and total cell number were assessed using 3- (4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) (Li et al., 2007). Experiments were performed in 24-well plates. Cells were treated in 0.5 mL phenol red-free medium supplemented with 10% CS-FBS, respective for different cell lines, as described in “Cell culture conditions”. Cells were treated for 1, 3, or 7 days as required by respective experiments. Cells were treated for 1 day, 3 days or 7 days. Medium was removed from the test wells at the end of treatment, and 0.5 mL freshly prepared treatment medium that contained 0.1% (w/v) MTT was added to each well. Cells were cultured at 37 °C for 2.0 hr, 0.5 mL solublization solution (20% SDS in 0.02 M HCl in H2O) was added to each well and the plate swirled to mix thoroughly. The mixed content in the plates was incubated at 37°C overnight, and the contents mixed again by vortexing. A 100 μl sample from each well was transferred to wells of a 96-well plate, and absorbance read at 570 nm. Each experiment was repeated 4 times independently.

Androgen responsive element (ARE) – mediated luciferase reporter assay for AR activity

ARE-luciferase assays were performed to evaluate the AR stimulatory effect of androgens as described (Wu et al., 2011). Cells were seeded in 6-well plates with 3 × 105 LAPC-4 or VCaP cells per well, and were incubated for 3 days and 7 days, respectively. Cells were transfected with the ARE-luciferase promoter-driven reporter plasmid using Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in Opti-MEM medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific) overnight following the manufacturer’s instruction. Transfected cells were trypsinized using trypsin-EDTA, washed once with medium and plated in 24-well plates at 1.5 × 105 cells per well in culture medium supplemented with 10% CS-FBS. Cells were cultured for 1 day, and treated for 1 day to evaluate AR activity. After incubation cells were rinsed 3 times with phosphate-buffered saline PBS, and cells were lysed by addition of 100 μl 1× reporter lysis buffer (RLB) (Promega, Madison, WI) to each well. The plates containing lysates were shaken on a plate shaker at 250 rpm for 10 min, and frozen at −80 °C. The frozen lysates were thawed at room temperature, transferred to clean Eppendorf tubes and centrifuged at 10,000× g for 10 min. A portion of the supernatant to be used for the luciferase assay was taken for protein determination using the BCA protein assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific) to obtain the total amount of protein (mg) in the lysate. Luciferase activity of the supernatant was measured using the Luciferase Assay System reagent (Promega). Luminescence was measured using a luminescence plate reader. The luciferase activity was expressed as relative luminescent unit (RLU) per μg of protein. Experiments were set up in 4 replicates, and luciferase activity in each sample was analyzed in triplicate.

Ex vivo experiments using fresh clinical human prostate tissue specimens

Metabolism of DHEAS and DHEA to DHT in intact tissue specimens was evaluated ex vivo in fresh remnant prostate tissue specimens. Fresh prostate tissue specimens were received in phenol red-free RPMI1640 supplemented with 10% CS-FBS. Experiments were set up within 3 hr of reception of the tissue. Experiments were set up in 300 μl medium per well in 48-well plates. Tissue specimens were cut into 2-3 mm3 pieces and 2-3 pieces of tissue were transferred into each well in 48-well plates. Upon the transfer of tissue specimens into the wells, all liquid that accompanied the tissue specimens was removed using sterile pipette tips and blotting with sterile Q-tips, and the tissue was rinsed 3 times with phenol red-free RPMI1640 supplemented with 10% CS-FBS. Residual medium was fully removed as described previously before 300 μl of phenol red-free RPMI1640 supplemented with 10% CS-FBS containing respective treatment agents was added into the well. Tissue specimens were incubated for 1 or 4 days during which medium samples were harvested and stored at −80 °C. At the end of treatment, the tissue specimens in each well were transferred to an Eppendorf tube which was weighed individually, and the residual liquid was removed thoroughly using pipette tips and blotting with Q-tips before the tissue and the tube were weighed together. Final tissue weight was reached by subtraction of the weight of the empty Eppendorf tube from the total weight of the tube and the tissue. DHT or DHEA in culture medium was measured using ELISA, and the weight of tissue in each sample (g) was used to normalize DHT or DHEA production.

In vivo experiments

Male severe combined immune deficiency (SCID) mice (Lab Animal Shared Resource at RPCCC), or Hsd:Athymic Nude-Fox1nu nude mice (Envigo, Indianapolis, IN), were purchased at 5 weeks of age, and experimental procedures were initiated when mice were 6 weeks old. Mice were surgically castrated, and silastic tubing (catalog number 508-008 from VWR, Radnor, PA) packed with T was implanted subcutaneously onto the mice during surgery. The procedure produced mice that had minimum inter-individual variations in circulating T; and the established circulating T levels were similar to the levels in adult male humans. The mice were inoculated subcutaneously with 2 × 106 VCaP cells suspended in 0.1 mL Matrigel (Cat#356237, Corning Life Sciences, Corning, NY) 3 days after T-silastic tubing implantation. Treatment of each individual mouse was started when the size of the tumor on the mouse reached 300 mm3. T-silastic tubing remained on the mice in the control group. T-silastic tubing was removed and an empty silatic tubing was implanted on each mouse in the castration group. T-silatic tubing was removed and a silastic tubing packed with DHEA was implanted on each mouse in the castration plus DHEA group. Tumor size was monitored twice a week with a caliper. Tumor size was calculated using the equation: π/6 × L × W2, where L and W were length and width of a tumor, respectively (Tomayko and Reynolds, 1989). Mice were treated up to 8 weeks, or when tumor size reached 2000 mm3. The effect on tumor growth between treatments was evaluated using a growth rate-based approach (Hather et al., 2014). Briefly, the size of each tumor over the time course was transformed to log scale, growth rate of each tumor was calculated using the transformed tumor sizes and the corresponding time intervals. Ratios of growth rates of tumors on mice treated with various conditions were calculated and statistically analyzed. All experimental procedures were approved by the RPCCC Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and were performed by staff at the RPCCC Mouse Tumor Model Resources (MTMR) core facility.

Reverse transcription and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

Cell lines were treated without T (as controls) or 1 nM T for 24 hr in respective phenol red-free medium supplemented with 10% CS-FBS as described in “Cell culture conditions”. RNA preparation and cDNA preparation were performed as described previously (Wu et al., 2013). Briefly, RNA was prepared using the QiaShredder Kit and the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). cDNA was generated using the SuperScript VILO cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Real-time PCR primers for STS and β-actin were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Real-time PCR reactions were performed using the Taqman Universal PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and an Applied Biosystems 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System (Foster City, CA). Expression levels of STS relative to the expression levels of β-actin were calculated using the equation: STS/ β-actin = 2−(CtSTS−Ctactin), where CtSTS and Ctactin were real-time PCR cycle numbers of STS and β-actin, respectively.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

TMA sections were de-paraffinized, rehydrated through an alcohol gradient, and antigen retrieved using a Reveal Decloaker (Biocare Medical, Concord, CA) for 30 min at 110°C and 5.5 - 6.0 psi. Sections were blocked for endogenous peroxidase activity using 3% H2O2 in dd-H2O for 15 min at room temperature, washed in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.8), and blocked with Background Punisher (Biocare Medical) for 10 min at room temperature to reduce non-specific staining. Non-immune control rabbit IgG (LSBio, Seattle, WA), or rabbit anti-human STS antibody (Atlas Antibodies, Bromma, Sweden), was diluted in Renoir Red Diluent (Biocare Medical) and used at 0.0025 mg IgG/mL, or 0.002 mg IgG/mL, respectively. Sections were incubated overnight with the diluted antibodies at 4°C. Following incubation with the primary antibody, slides were incubated with the Biocare MACH4 mouse probe and MACH 4 HRP polymer (Biocare Medical) at room temperature for 15 min, and immunostaining was developed using diaminobenzidine (Sigma-Aldrich). The sections were counterstained with hematoxylin (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), dehydrated and mounted using Cytoseal 60 permanent mounting medium (Richard-Allen Scientific, Kalamazoo, MI). Sections were scanned using an Aperio ScanScope XT (Leica Biosystems, Buffalo Grove, IL). Images were processed using Aperio eSlide Manager.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) of androgens

ELISA kits for DHT or DHEA measurement were purchased from Alpco (Salem, NH). A portion of each freshly prepared treatment medium was stored at −80 °C; the medium represents a “clean medium” control. Medium samples were harvested at the end of treatment, spun at 1000× g at 4 °C for 10 min to collect supernatant; and the medium termed “culture medium”. Clean medium and culture medium samples were analyzed using ELISA following manufacturer’s instruction.

Measurement of androgen levels was in μg/mL for DHT and ng/mL for DHEA. Androgen measurements of each “culture medium” sample had the measurement of the corresponding “clean medium” sample subtracted in order to eliminate cross-reactivity for the specific androgen used for the treatment. This step of data processing may lead to underestimating the amount of an androgen produced from the treating androgen, but fully removed the concern for false reading generated by cross-reactivity. The cross reactivity of DHEAS and DHEA with DHT was determined using the DHT ELISA kit, and was 0.06% and 0.04% in RPMI1640 supplemented with 10% CS-FBS, respectively; and 0.05% and 0.06% in DMEM supplemented with 10% CS-FBS, respectively. The cross reactivity of DHEAS with DHEA was determined using the DHEA ELISA kit, and no cross reactivity was detected in RPMI1640 supplemented with 10% CS-FBS and DMEM supple lamented with 10% CS-FBS, respectively. The detailed cross reactivity assay was presented in Supplementary Table S-1. The performance of the DHT and the DHEA ELISA kits was evaluated in RPMI1640 supplemented with 10% CS-FBS and in DMEM supplemented with 10% CS-FBS containing known amount of additional DHT or DHEA (Supplementary Figure S1). The MTT assay was performed in the same tissue culture plate after removal of culture medium sample for androgen analyses. Total androgen content in each medium sample was calculated using androgen concentration multiplied by medium volume in each well (0.5 mL), and normalized using MTT as a measure of cell content: androgen concentration was expressed in pg/MTT for DHT, or ng/MTT for DHEA. Each experiment was performed in 4 replicates, and androgen levels in each sample was measured and averaged in duplicate. Curves that correlated cell numbers and MTT units (OD570) for all the cell lines were provided to facilitate the comparison of results based on cell numbers (Supplementary Figure S2).

Statistical analysis

Student’s t-test was conducted to evaluate statistical significance of results in all experiments. A difference was determined to be significant with a p value < 0.05.

Results

STS expression in PCa tissue and PCa cell lines and conversion of DHEAS to DHEA by PCa cell lines

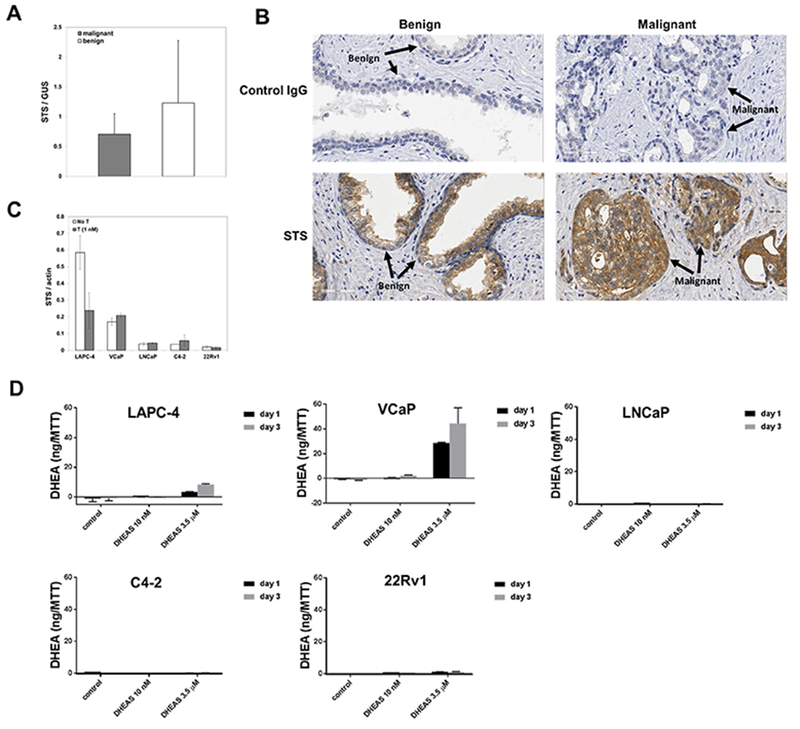

The expression of STS mRNA in human PCa tissue and matched adjacent benign prostate tissue was confirmed by qRT-PCR (Fig 1A). Although STS mRNA seemed to be lower in PCa tissue compared to benign tissue, this difference was not statistically significant. IHC staining of STS protein in the matched tissue specimens confirmed the qRT-PCR results (Fig 1B). STS was expressed primarily in epithelial cells, and in some cells in the stromal tissue in both PCa and benign prostate tissue, whereas, non-immune control IgG did not stain prostate tissue.

Fig 1.

Expression of STS in human prostate cancer tissue and human prostate cancer cell lines, and the conversion of DHEAS to DHEA by prostate cancer cell lines (A) STS expression in benign human prostate tissue and prostate cancer tissue at mRNA levels (n=20); (B) STS expression at protein levels in matched benign and malignant prostate tissue specimens; (C) STS expression at mRNA levels in human prostate cancer cell lines; (D) DHEA production by prostate cancer cell lines treated with DHEAS for 1 day or 3 days. DHEA in the culture medium was normalized against cell numbers, which was indicated by units of OD570 measured using the MTT assay.

Expression of STS at the mRNA levels varied among human PCa cell lines (Fig 1C). LAPC-4 and VCaP cells expressed the highest levels of STS. Treatment with T reduced the expression of STS in LAPC-4 cells but not in the other cell lines. The two cell lines with the highest levels of STS mRNA, LAPC-4 and VCaP, demonstrated the highest level of metabolism of DHEAS to DHEA, therefore, presumably the highest STS activity (Fig 1D). STS activity was higher in VCaP cells compared to LAPC-4 cells even though STS transcripts were more abundant in LAPC-4 cells (in absence of T).

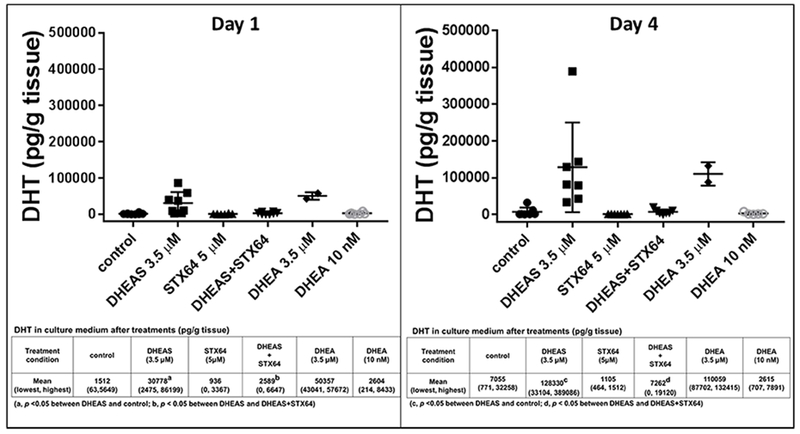

DHT production from DHEA and DHEAS by fresh clinical prostate tissue specimens ex vivo

Fresh, intact human prostate tissue specimens converted both DHEA and DHEAS to DHT (Fig 2). Tissue specimens treated with 3.5 μM DHEAS produced DHT (physiologic level). The STS inhibitor, STX64, reduced DHT production from DHEAS. Tissue specimens treated with 3.5 μM DHEA (physiologic level of DHEAS) produced DHT. In contrast, tissue specimens treated with a physiologic concentration of DHEA (10 nM) did not produce detectable levels of DHT. DHT production by the same amount of tissue from an equimolar (3.5 μM) concentration of DHEA or DHEAS was similar. The accumulation of DHT in the culture medium of tissue specimens treated with 3.5 μM DHEAS or DHEA increased with time. Note, there was modest DHT production in untreated controls possibly representing metabolism of residual substrates in the fresh tissue.

Fig 2.

DHT production by prostate tissue ex vivo was STS-dependent. Inserted tables showed the exact values of DHT production, in each treatment presented in the respective bar graph at the top in the format of mean and range (lowest value, highest value). DHEAS 3.5 μM and STX64 5 μM were used in the combination treatments.

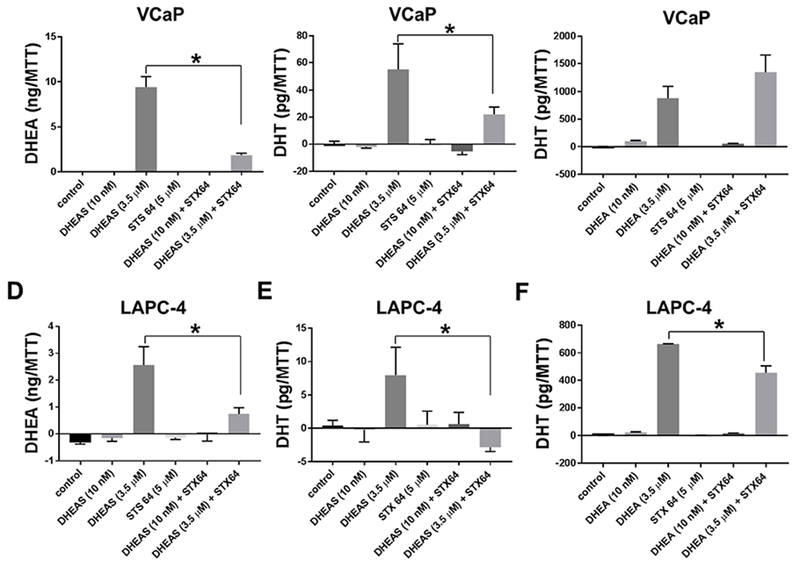

DHEA and DHT production by PCa cell lines VCaP and LAPC-4 using DHEAS was STS-dependent.

VCaP cells converted DHEAS to DHEA, whereas, STX64 treatment reduced DHEA production (Fig 3A). VCaP cells converted both DHEA and DHEAS to produce DHT (Fig 3B and 3C, respectively). The amount of DHT produced depended on the concentrations of DHEA or DHEAS. DHT production was low when cells were treated with DHEA or DHEAS at 10 nM, the physiological concentration of circulating DHEA. DHT production was higher when cells were treated with DHEA or DHEAS at 3.5 μM, the physiological concentration of circulating DHEAS. DHEA appeared to be a preferred substrate for DHT production compared to DHEAS since more DHT was produced from DHEA at either treatment concentrations.

Fig 3.

DHEA and DHT production by prostate cancer cell lines VCaP (Panels A-C) and LAPC-4 (Panels D-F) using DHEAS was STS-dependent. (A) & (D), DHEA production; (B) & (E), DHT production by cells treated with DHEAS; (C) & (F), DHT production by cells treated with DHEAS. Cells were treated for 3 days. Androgens in the culture medium were normalized against cell numbers, which was indicated by units of OD570 measured using the MTT assay. * p < 0.05.

STX64 inhibited DHT production in the DHEAS treatment groups (Fig 3B&E), and had no effect on DHT production by VCaP cells treated with 3.5 μM DHEA (Fig 3C). STX64 reduced slightly DHT production by LAPC-4 cells treated with 3.5 μM DHEA (Fig 3F), but to a lesser extend compared to the reduction of DHT production by LAPC-4 cells treated with 3.5 μM DHEAS. The inhibitory activity of STX64 was specific to DHT production from DHEAS suggesting that STS was critical for DHT production from DHEAS. The ability of LAPC-4 cells to metabolize DHEA, or DHEAS, for DHT production was lower than that of VCaP cells, whereas the sensitivity of LAPC-4 DHT production from DHEAS to the inhibitory effect of STX64, was similar to VCaP cells (Fig 3D-F).

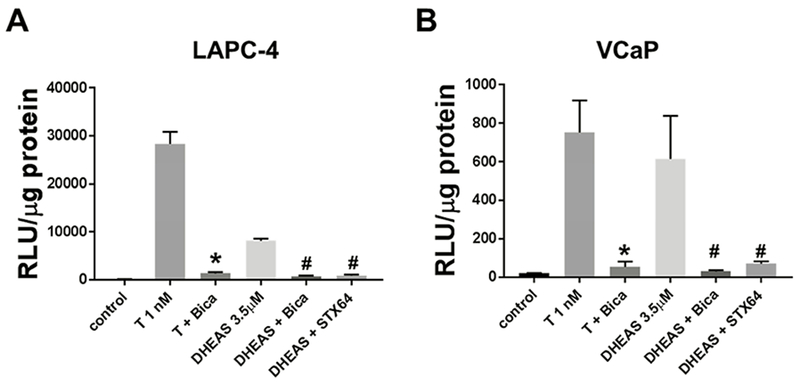

Stimulation of AR activity by DHEAS

AR-mediated transcriptional activity in LAPC-4 and VCaP cells was stimulated by incubation with DHEAS (Fig 4A and B, and STX64 reversed AR stimulation by DHEAS. T at 1 nM, and DHEAS at 3.5 μM, both activated AR transactivation, with AR activation by the androgens/metabolites inhibited by the AR antagonist bicalutamide. Bicalutamide alone and STX64 alone did not have effect on AR activity in cells treated in the absence of T or DHEAS (data not shown).

Fig 4.

DHEAS activation of AR in LAPC-4 and VCaP cell lines was diminished by AR antagonist bicalutamide (Bica) and STX64. T 1 nM, Bicalutamide 10 μM, DHEAS 3.5 μM, and STX64 5 μM were used in the combination treatments. Cells were treated for 24 hr. * p < 0.05 compared to T 1 nM. # p < 0.05 compared to DHEAS 3.5 μM.

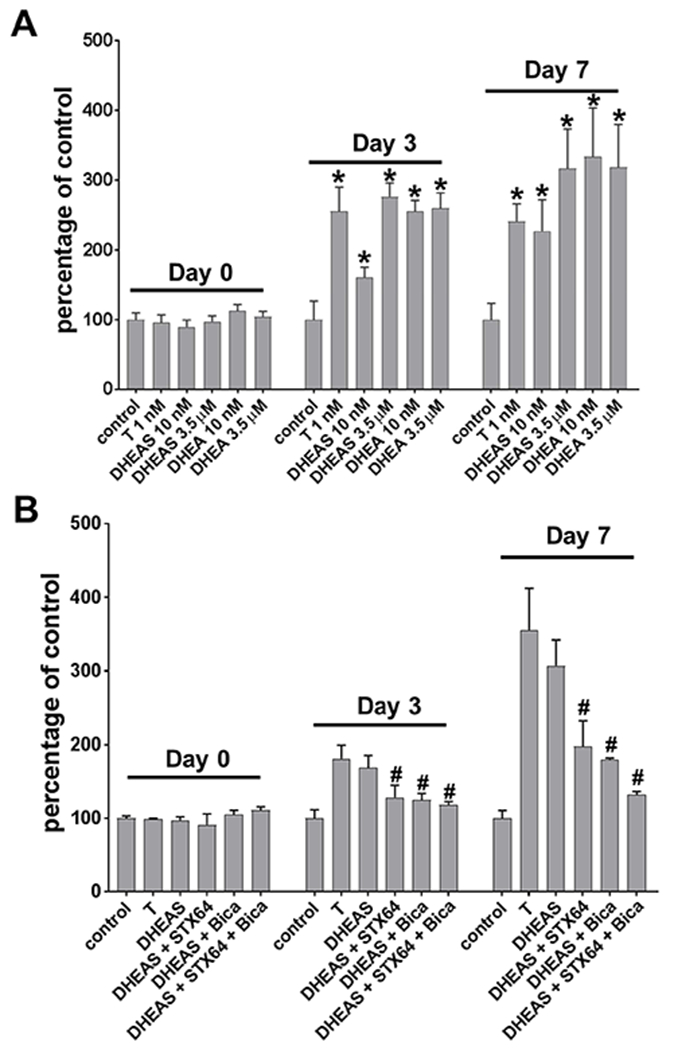

Stimulation of PCa cell growth by DHEA and DHEAS

Both DHEA and DHEAS stimulated growth of VCaP cells in the absence of exogenous T in the medium (Fig 5A). The growth-stimulatory effect of DHEAS was dose-dependent,” where DHEA has been removed. DHEA stimulated growth more effectively than DHEAS when both were used at a 10 nM concentration, whereas, DHEA and DHEAS stimulated growth to a similar degree when both were used at a 3.5 μM concentration. DHEAS-stimulated growth was inhibited by STX64, indicating that DHEAS-stimulation of growth required STS conversion of DHEAS to DHEA. Lastly, bicalutamide reversed partially the DHEAS-stimulated growth, indicating that growth stimulation by DHEAS was at least partially AR-dependent (Fig 5B).

Fig 5.

AR-dependent stimulation of growth by adrenal androgens. (A) DHEAS and DHEA stimulated growth of VCaP cells. (B) DHEAS (DS) stimulated growth was diminished by AR antagonist bicalutamide (Bica) and STX64 (B). Cells were treated for 3 days and 7 days. Growth was assessed using MTT assay. Data were presented in percentage to untreated controls at each time point (day). * p < 0.05 compared to control. # p < 0.05 compared to DHEAS.

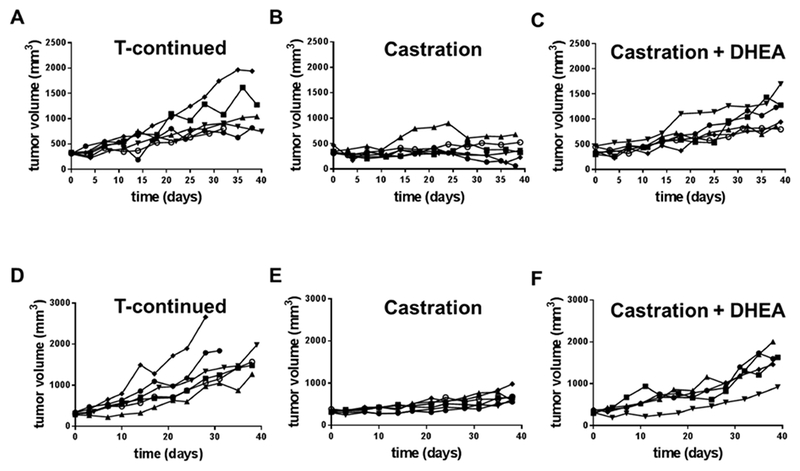

DHEA sustained growth of VCaP xenograft in castrated mice

The volume of VCaP xenografts growing in castrated nude mice did not increase over the time course of the experiment, while the volume of VCaP xenografts in mice supplemented with T increased continuously over the time course of the experiment. VCaP xenografts growing in castrated mice supplemented with DHEA maintained a rate of increase similar to in animals supplemented with T (Fig 6A-C). VCaP xenografts on SCID mice demonstrated the same growth patterns of tumor growth as on nude mice in response to T supplementation, castration without supplementation, and castration in combination with DHEA supplementation, respectively (Fig 6D-F). Growth rate analysis showed that castration reduced the growth rate of tumors by ~50% compared to tumor growth on mice treated with T. DHEA increased tumor growth compared to tumor growth on castrated mice, and DHEA supported tumor growth at rates comparable to T (Table 1).

Fig 6.

DHEA sustained growth of VCaP xenograft after castration in SCID mice (A-C) and nude mice (E-F). Each line represented the growth curve of the xenograft in one mouse.

Table-1.

Ratios of growth rates between treatment groups that were compared.

| Mouse strain | Comparison between treatments | Growth Rate-based ratio | p value | significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nude | castration / T | 0.498 | 0.005 | * |

| (castration+DHEA) / castration | 1.867 | 0.009 | * | |

| (castration+DHEA) / T | 0.931 | 0.520 | ns | |

| SCID | castration / T | 0.522 | 0.001 | * |

| (castration+DHEA) / castration | 1.493 | 0.0002 | * | |

| (castration+DHEA) / T | 0.780 | 0.058 | ns |

ns, not significant (p ≥ 0.05);

, significant (p < 0.05).

Discussion

This study reports several unique findings relevant to the ability of adrenal androgens to rescue the loss of testicular androgens due to ADT as measured by production of DHT, maintenance of AR activity and tumor growth. First, STS was expressed both in benign and malignant prostate tissue, in agreement with previous reports of the expression of STS in the prostate (Nakamura et al., 2006,Klein et al., 1988,Klein et al., 1988,Voigt and Bartsch, 1986,Farnsworth, 1973,Cowan et al., 1977,Klein et al., 1989). Expression of STS at the mRNA level and protein level were comparable between benign and malignant prostate tissue. It is not clear at the moment whether the expression of STS is different in primary PCa and advanced, metastatic PCa. Therefore, further research is needed to determine whether the ability of primary PCa to utilize DHEAS is preserved, or increased, in metastatic CRPC. Second, fresh clinical specimens of prostate tissue utilized DHEA and DHEAS to produce DHT ex vivo. Both DHEA and DHEAS were effective substrates for DHT production only at concentrations in the μM range, the physiologic concentration of DHEAS, but not DHEA. The adrenal androgens were much less effective substrates at concentrations in the nM range, the physiologic concentration of DHEA. This finding confirmed a previous report that DHEA was not a substrate for intracrine DHT production in human PCa tissue (Fankhauser et al., 2014), but suggests that when there is sufficient DHEAS available, both are potential substrates. While DHEA is not available in the μM range physiologically, DHEAS is available in μM range in circulation and may be converted to DHEA at sufficient levels to raise the intracellular concentration of DHEA to biologically active levels (Rainey et al., 2002,Travis et al., 2007,Wurzel et al., 2007,Ryan et al., 2007). Due to the high circulation concentrations of DHEAS, although DHEA and DHEAS could both be converted to DHT when they were present at μM concentrations, DHEAS appears to be the preferred androgen between the two that is available to PCa cells at biologically active concentrations. Third, both DHEA and DHEAS can be metabolized by PCa cell lines to produce DHT, activate AR-mediated transactivation and stimulate growth. Fourth, STS activity and DHT production from DHEAS varied among the PCa cell lines, however, the efficiency of DHT production did not always correlate with STS activity indicated by conversion of DHEAS to DHEA. The discordance between STS activity and conversion of DHEA to DHT in the cell lines suggests that co-existence of PCa cells with high STS activity and cancer cells with high DHEA metabolizing activity could form “symbiotic” niches where cancer cells containing either activity benefit from each other to form a collective ability of using adrenal androgens. In addition, cells with both activities may represent those with the most potential to progress.

Studies of DHT production from DHEA or DHEAS based in intact prostate tissue cultured ex vivo appear physiologically relevant. DHT accumulation in culture medium of tissue specimens incubated ex vivo with 3.5 μM DHEA or DHEAS was in a nM range on day1 after treatment, and at least an order-of-magnitude greater on day 4 after initiation of treatment. Since the volume of the tissue culture medium was commonly ~10-fold greater than the volume of the tissue specimens, DHT would accumulate in the tissue to much higher concentrations if the produced DHT was retained within the tissue. Regardless, levels of DHT produced by the tissue specimens were more than sufficient to activate AR. The conversion rates DHEAS to DHT, or DHEA to DHT were calculated using the concentrations of produced DHT by tissue specimens treated with 3.5 μM of DHEAS or DHEA. The conversion rates also depended on the amount of tissue presented in each single treatment. The average amount of tissue used in each single treatment condition was ~ 0.05 g per well. In these experimental settings, the rate of conversion to DHT was 0.39% and 0.95% for DHEAS and DHEA on day 1, respectively; and 1.32% and 1.98% for DHEAS and DHEA on Day 4, respectively. Further studies are needed to evaluate the conversion of these adrenal androgens to DHT in comparison to T to DHT conversion in order to fully appreciate the activity of using DHEAS or DHEA by prostate tissue.

A limitation of the present study was that the ELISA analyses did not decisively determine whether, or how much, of the production of DHT from DHEA was through the production of androstenediol and T, or through androstenedione and androstanedione without T production. These questions will be addressed using liquid chromatography tandem mass-spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). In addition, metabolites downstream of DHT, including the sulfate- or UGT-conjugates, were not examined. Therefore, the actual efficiency of DHT production may be underestimated. Regardless, the data demonstrate that DHT production from DHEA/DHEAS was sufficient to activate AR, and presumably stimulate cancer cell growth. Stimulation of VCaP xenograft growth by DHEA in castrate mouse hosts provided a proof-of-concept that adrenal androgens could maintain tumor growth. However, a significant limitation of in vivo studies in the SCID and the nude mouse models was that the effect of DHEAS on post-castration growth of the VCaP xenograft could not be evaluated. DHEAS could not be detected using a DHEAS ELISA kit from Alpco in mouse serum at even short time points after administration despite evaluation of multiple approaches for delivery DHEAS, including: oral gavage, silastic tubing implant, and intraperitoneal injection (data not shown). DHEAS might be disposed of from the mouse by high efficient clearance by the kidney, since large quantities of DHEAS were detected in the urine of DHEAS-treated mice (unpublished data).

Targeting metabolism of DHEAS to DHEA with STS inhibitors, such as STX64, has been proposed as a new approach to treat sex hormone-related cancers, including breast cancer and PCa, and have been tested in phase I and phase II clinical trials (Woo et al., 2011,Williams, 2013,Day et al., 2009,McNamara et al., 2013). A phase I trial with STX64 demonstrated promising results as indicated by induction of stable disease in breast cancer patients (Stanway et al., 2006,Coombes et al., 2013). A phase II trial following chemotherapy of post-menopausal endometrial cancer patients was discontinued due to a lack of beneficial effects (Ipsen, 2013). Results of other trials on STX64 in patients with breast cancer or PCa were summarized by McNamara KM et al. (McNamara et al., 2013). In the present study, the STS inhibitor STX64 blocked DHT production from DHEAS, diminished AR activity and inhibited growth stimulation by DHEAS. The results suggest that conversion of the highly available DHEAS to DHEA, thereby raising the effective intracellular concentration of DHEA, is required to produce bioactive levels of DHEA. The efficiency of DHEAS to DHEA conversion, and DHEA or DHEAS to DHT conversion require further investigation using more accurate assessment of androgens such as mass spectrometry. Additionally, since cells may rely on transporters for DHEAS uptake (Roth et al., 2012,Obaidat et al., 2012,Cho et al., 2014), whether and how DHEAS uptake transporters may contribute to the utility of DHEAS by PCa cells need to be studied. In patients treated with castration or abiraterone, circulating levels of DHEAS remained in the μM range, whereas, circulating DHEA was diminished to concentrations below nM (Snaterse et al., 2017). Consequently, targeting the metabolic conversion of DHEAS to DHEA with STS inhibitors represent a logical adjuvant therapy in combination with ADT or abiraterone treatment.

Prostatic tissue concentrations of DHEA and DHEAS based on published results are 20 nM and 40 nM, respectively (Wurzel et al., 2007,Ryan et al., 2007,Nishiyama et al., 2007,Mostaghel et al., 2007,Litman et al., 2006,Page et al., 2006,Mohler et al., 2004,Mohler et al., 2004). The prostate tissue concentration of DHEA is higher than in circulation, whereas, the intra-prostatic level of DHEAS is much lower than in circulation. The tissue levels of DHEAS and DHEA presumably represent an equilibrium that results from continuing uptake from the circulation, metabolic conversion of DHEAS to DHEA and conjugation/excretion of DHT. Consequently, it is not clear whether, and how much, DHT may be produced from DHEA or DHEAS in prostate tissue continuously exposed to adrenal androgens. The ex vivo and in vitro experiments in the present study were performed over a short time period, and in a closed system. Since the ex vivo system is closed, it will allow in future studies the analysis of all products of metabolism, including conjugates, which would be almost impossible to do in vivo. On the other hand, growth of VCaP xenografts was maintained in castrated mice that were treated with DHEA, and the serum concentration of DHEA in DHEA-treated mice was 16.5 nM and 24.7 nM in SCID mice and nude mice, respectively (Supplementary Data Fig S3), similar to the physiological circulating concentration in human. This result suggests that long-term exposure to DHEA may be beneficial to PCa cells. Nevertheless, the data demonstrate that prostate tissue is equipped with effective metabolic capacity to produce DHT using adrenal androgens. Therefore, this capability should not be neglected, while better targeting approaches are needed to fully block the capacity of using adrenal androgens.

There are at least two circumstances under which PCa cells may be exposed directly to the μM level of DHEAS present in the circulation. One is when PCa cells are actually in the circulation during metastasis. The other is when locally advanced PCa is treated with ADT. The prostatic endothelium undergoes apoptotic cell death, leading to acute de-endothelialization after ADT (Godoy et al., 2011). The loss of the selectively permeable endothelial cell-mediated blood-tissue barrier may expose PCa cells to circulating levels of DHEAS.

In summary, the results of the present studies demonstrate the potential of prostate tissue, and PCa cells to metabolize adrenal androgens for DHT production. Although DHEA may be preferred over DHEAS by PCa cells, only DHEAS is available for DHT production at physiologically relevant concentrations. Therefore, there is place for STS inhibitors in PCa treatment. Abiraterone is used to treat CRPC and reduces effectively the serum DHEAS and DHEA to 0.14 - 0.4 μM and 0.08 – 2.7 nM, respectively (Snaterse et al., 2017,McKay et al., 2017,Attard et al., 2008,Taplin et al., 2014). Although the significance of the residual serum DHEAS and DHEA in intratumoral T and DHT synthesis needs further investigations, blocking of DHEAS and DHEA for DHT synthesis may facilitate complete ADT.

Supplementary Material

Prostate tissue and prostate cancer cell lines converted DHEAS and DHEA to DHT;

Conversion of DHEAS to DHT depended on steroid sulfatase;

DHEAS and DHEA activated AR and stimulated growth of prostate cancer cell lines;

DHEAS-stimulated growth in vitro was STS- and AR-dependent;

DHEA sustained growth of prostate cancer cell line VCaP in castrated mice.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants 1R21CA191895-01 (to Y.W.) and 1R01CA193829-01A1 (to G.J.S. and Y.W.) from the National Cancer Institute, an award DOH01-C30314GG-3450000 (to Y.W.) from the New York State Department of Health, two awards from the Roswell Park Alliance Foundation (to Y.W.), an award from the Roswell Park Alliance Foundation (to L.T.), and National Cancer Institute (NCI) grant P30CA16056 involving the use of Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center’s Shared Resources.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- [1].Dai C, Heemers H and Sharifi N, 2017. Androgen signaling in prostate cancer, Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 7 10.1101/cshperspect.a030452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Stuchbery R, McCoy PJ, Hovens CM and Corcoran NM, 2017. Androgen synthesis in prostate cancer: do all roads lead to Rome?, Nat Rev Urol 14, 49–58. 10.1038/nrurol.2016.221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Mohler JL, 2008. A role for the androgen-receptor in clinically localized and advanced prostate cancer, Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 22, 357–72. 10.1016/j.beem.2008.01.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Wilson EM and French FS, 1976. Binding properties of androgen receptors. Evidence for identical receptors in rat testis, epididymis, and prostate, J Biol Chem 251, 5620–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kamrath C, Hochberg Z, Hartmann MF, Remer T and Wudy SA, 2012a. Increased activation of the alternative “backdoor” pathway in patients with 21-hydroxylase deficiency: evidence from urinary steroid hormone analysis, J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97, E367–75. 10.1210/jc.2011-1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Kamrath C, Hartmann MF, Remer T and Wudy SA, 2012b. The activities of 5alpha-reductase and 17,20-lyase determine the direction through androgen synthesis pathways in patients with 21-hydroxylase deficiency, Steroids. 77, 1391–7. 10.1016/j.steroids.2012.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Mohler JL, Titus MA, Bai S, Kennerley BJ, Lih FB, Tomer KB and Wilson EM, 2011. Activation of the androgen receptor by intratumoral bioconversion of androstanediol to dihydrotestosterone in prostate cancer, Cancer Res 71, 1486–96. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Mostaghel EA, 2013. Steroid hormone synthetic pathways in prostate cancer, Transl Androl Urol 2, 212–227. 10.3978/j.issn.2223-4683.2013.09.16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Fiandalo MV, Wilton J and Mohler JL, 2014. Roles for the backdoor pathway of androgen metabolism in prostate cancer response to castration and drug treatment, Int J Biol Sci 10, 596–601. 10.7150/ijbs.8780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Pretorius E, Africander DJ, Vlok M, Perkins MS, Quanson J and Storbeck K-H, 2016. 11-Ketotestosterone and 11-ketodihydrotestosterone in castration resistant prostate cancer: potent androgens which can no longer be ignored, PLOS ONE. 11, e0159867 10.1371/journal.pone.0159867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Storbeck K-H, Bloem LM, Africander D, Schloms L, Swart P and Swart AC, 2013. 11β-Hydroxydihydrotestosterone and 11-ketodihydrotestosterone, novel C19 steroids with androgenic activity: A putative role in castration resistant prostate cancer?, Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 377, 135–146. 10.1016/j.mce.2013.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Pretorius E, Arlt W and Storbeck K-H, 2017. A new dawn for androgens: Novel lessons from 11-oxygenated C19 steroids, Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 441, 76–85. 10.1016/j.mce.2016.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Bloem LM, Storbeck KH, Swart P, du Toit T, Schloms L and Swart AC, 2015. Advances in the analytical methodologies: Profiling steroids in familiar pathways-challenging dogmas, J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 153, 80–92. 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2015.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Rainey WE, Carr BR, Sasano H, Suzuki T and Mason JI, 2002. Dissecting human adrenal androgen production, Trends Endocrinol Metab 13, 234–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Travis RC, Key TJ, Allen NE, Appleby PN, Roddam AW, Rinaldi S, Egevad L, Gann PH, Rohrmann S, Linseisen J, Pischon T, Boeing H, Johnsen NF, Tjonneland A, Overvad K, Kiemeney L, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Bingham S, Khaw KT, Tumino R, Sieri S, Vineis P, Palli D, Quiros JR, Ardanaz E, Chirlaque MD, Larranaga N, Gonzalez C, Sanchez MJ, Trichopoulou A, Bikou C, Trichopoulos D, Stattin P, Jenab M, Ferrari P, Slimani N, Riboli E and Kaaks R , 2007. Serum androgens and prostate cancer among 643 cases and 643 controls in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition, Int J Cancer. 121, 1331–8. 10.1002/ijc.22814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Wurzel R, Ray P, Major-Walker K, Shannon J and Rittmaster R, 2007. The effect of dutasteride on intraprostatic dihydrotestosterone concentrations in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia, Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 10, 149–54. 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Ryan CJ, Halabi S, Ou SS, Vogelzang NJ, Kantoff P and Small EJ, 2007. Adrenal androgen levels as predictors of outcome in prostate cancer patients treated with ketoconazole plus antiandrogen withdrawal: results from a cancer and leukemia group B study, Clin Cancer Res 13, 2030–7. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Snaterse G, Visser JA, Arlt W and Hofland J, 2017. Circulating steroid hormone variations throughout different stages of prostate cancer, Endocr Relat Cancer. 24, R403–R420. 10.1530/ERC-17-0155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Rege J, Nakamura Y, Satoh F, Morimoto R, Kennedy MR, Layman LC, Honma S, Sasano H and Rainey WE, 2013. Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry analysis of human adrenal vein 19-carbon steroids before and after ACTH stimulation, The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 98, 1182–1188. 10.1210/jc.2012-2912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].du Toit T, Bloem LM, Quanson JL, Ehlers R, Serafin AM and Swart AC, 2017. Profiling adrenal 11β-hydroxyandrostenedione metabolites in prostate cancer cells, tissue and plasma: UPC2-MS/MS quantification of 11β-hydroxytestosterone, 11keto-testosterone and 11keto-dihydrotestosterone, The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 166, 54–67. 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2016.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Nussbaumer P and Billich A, 2004. Steroid sulfatase inhibitors, Med Res Rev 24, 529–76. 10.1002/med.20008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Purohit A and Foster PA, 2012. Steroid sulfatase inhibitors for estrogen- and androgen-dependent cancers, J Endocrinol 212, 99–110. 10.1530/JOE-11-0266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Reed MJ, Purohit A, Woo LW, Newman SP and Potter BV, 2005. Steroid sulfatase: molecular biology, regulation, and inhibition, Endocr Rev 26, 171–202. 10.1210/er.2004-0003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Nakamura Y, Suzuki T, Fukuda T, Ito A, Endo M, Moriya T, Arai Y and Sasano H, 2006. Steroid sulfatase and estrogen sulfotransferase in human prostate cancer, Prostate. 66, 1005–12. 10.1002/pros.20426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Klein H, Bressel M, Kastendieck H and Voigt KD, 1988. Quantitative assessment of endogenous testicular and adrenal sex steroids and of steroid metabolizing enzymes in untreated human prostatic cancerous tissue, J Steroid Biochem 30, 119–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Klein H, Bressel M, Kastendieck H and Voigt KD, 1988. Androgens, adrenal androgen precursors, and their metabolism in untreated primary tumors and lymph node metastases of human prostatic cancer, Am J Clin Oncol 11 Suppl 2, S30–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Voigt KD and Bartsch W, 1986. Intratissular androgens in benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostatic cancer, J Steroid Biochem 25, 749–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Farnsworth WE, 1973. Human prostatic dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate sulfatase, Steroids. 21, 647–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Cowan RA, Cowan SK, Grant JK and Elder HY, 1977. Biochemical investigations of separated epithelium and stroma from benign hyperplastic prostatic tissue, J Endocrinol 74, 111–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Klein H, Molwitz T and Bartsch W, 1989. Steroid sulfate sulfatase in human benign prostatic hyperplasia: characterization and quantification of the enzyme in epithelium and stroma, J Steroid Biochem 33, 195–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Fankhauser M, Tan Y, Macintyre G, Haviv I, Hong MK, Nguyen T, Pedersen J, Costello AJ, Hovens CM and Corcoran NM, 2014. Canonical androstenedione reduction is the predominant dource of signalling androgens in hormone refractory prostate cancer, Clin Cancer Res 20, 5547–5557. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Chang KH, Li R, Kuri B, Lotan Y, Roehrborn CG, Liu J, Vessella R, Nelson PS, Kapur P, Guo X, Mirzaei H, Auchus RJ and Sharifi N, 2013. A gain-of-function mutation in DHT synthesis in castration-resistant prostate cancer, Cell. 154, 1074–84. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Hettel D, Zhang A, Alyamani M, Berk M and Sharifi N, 2018. AR signaling in prostate cancer regulates a feed-forward mechanism of androgen synthesis by way of HSD3B1 upregulation, Endocrinology. 159, 2884–2890. 10.1210/en.2018-00283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Roth M, Obaidat A and Hagenbuch B, 2012. OATPs, OATs and OCTs: the organic anion and cation transporters of the SLCO and SLC22A gene superfamilies, Br J Pharmacol 165, 1260–87. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01724.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Obaidat A, Roth M and Hagenbuch B, 2012. The expression and function of organic anion transporting polypeptides in normal tissues and in cancer, Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 52, 135–51. 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010510-100556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Cho E, Montgomery RB and Mostaghel EA, 2014. Minireview: SLCO and ABC transporters: a role for steroid transport in prostate cancer progression, Endocrinology. 155, 4124–32. 10.1210/en.2014-1337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Klein KA, Reiter RE, Redula J, Moradi H, Zhu XL, Brothman AR, Lamb DJ, Marcelli M, Belldegrun A, Witte ON and Sawyers CL, 1997. Progression of metastatic human prostate cancer to androgen independence in immunodeficient SCID mice, Nat Med 3, 402–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Wu HC, Hsieh JT, Gleave ME, Brown NM, Pathak S and Chung LW, 1994. Derivation of androgen-independent human LNCaP prostatic cancer cell sublines: role of bone stromal cells, Int J Cancer. 57, 406–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Sobel RE and Sadar MD, 2005. Cell lines used in prostate cancer research: a compendium of old and new lines-part 2, J Urol 173, 360–72. 10.1097/01.ju.0000149989.01263.dc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Sobel RE and Sadar MD, 2005. Cell lines used in prostate cancer research: a compendium of old and new lines-part 1, J Urol 173, 342–59. 10.1097/01.ju.0000141580.30910.57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Fiandalo MV, Wilton JH, Mantione KM, Wrzosek C, Attwood KM, Wu Y and Mohler JL, 2018. Serum-free complete medium, an alternative medium to mimic androgen deprivation in human prostate cancer cell line models, Prostate. 78, 213–221. 10.1002/pros.23459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Li S, Zhou Y, Wang R, Zhang H, Dong Y and Ip C, 2007. Selenium sensitizes MCF-7 breast cancer cells to doxorubicin-induced apoptosis through modulation of phospho-Akt and its downstream substrates, Mol Cancer Ther 6, 1031–8. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Wu Y, Chhipa RR, Zhang H and Ip C, 2011. The antiandrogenic effect of finasteride against a mutant androgen receptor, Cancer Biol Ther 11, 902–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Tomayko MM and Reynolds CP, 1989. Determination of subcutaneous tumor size in athymic (nude) mice, Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 24, 148–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Hather G, Liu R, Bandi S, Mettetal J, Manfredi M, Shyu WC, Donelan J and Chakravarty A, 2014. Growth rate analysis and efficient experimental design for tumor xenograft studies, Cancer Inform. 13, 65–72. 10.4137/CIN.S13974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Wu Y, Godoy A, Azzouni F, Wilton JH, Ip C and Mohler JL, 2013. Prostate cancer cells differ in testosterone accumulation, dihydrotestosterone conversion, and androgen receptor signaling response to steroid 5alpha-reductase inhibitors, Prostate. 73, 1470–82. 10.1002/pros.22694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Woo LW, Purohit A and Potter BV, 2011. Development of steroid sulfatase inhibitors, Mol Cell Endocrinol 340, 175–85. 10.1016/j.mce.2010.12.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Williams SJ, 2013. Sulfatase inhibitors: a patent review, Expert Opin Ther Pat 23, 79–98. 10.1517/13543776.2013.736965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Day JM, Purohit A, Tutill HJ, Foster PA, Woo LW, Potter BV and Reed MJ, 2009. The development of steroid sulfatase inhibitors for hormone-dependent cancer therapy, Ann N Y Acad Sci 1155, 80–7. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2008.03677.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].McNamara KM, Nakamura Y, Miki Y and Sasano H, 2013. Phase two steroid metabolism and its roles in breast and prostate cancer patients, Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 4, 116 10.3389/fendo.2013.00116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Stanway SJ, Purohit A, Woo LW, Sufi S, Vigushin D, Ward R, Wilson RH, Stanczyk FZ, Dobbs N, Kulinskaya E, Elliott M, Potter BV, Reed MJ and Coombes RC, 2006. Phase I study of STX 64 (667 Coumate) in breast cancer patients: the first study of a steroid sulfatase inhibitor, Clin Cancer Res 12, 1585–92. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Coombes RC, Cardoso F, Isambert N, Lesimple T, Soulie P, Peraire C, Fohanno V, Kornowski A, Ali T and Schmid P, 2013. A phase I dose escalation study to determine the optimal biological dose of irosustat, an oral steroid sulfatase inhibitor, in postmenopausal women with estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer, Breast Cancer Res Treat 140, 73–82. 10.1007/s10549-013-2597-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Ipsen, 2013. Ipsen’s 2012 results and 2013 financial objectives. Ipsen, https://www.ipsen.com/media/press-relases/ipsens-2012-results-and-2013-financial-objectives-2/. [Google Scholar]

- [54].Nishiyama T, Ikarashi T, Hashimoto Y, Wako K and Takahashi K, 2007. The change in the dihydrotestosterone level in the prostate before and after androgen deprivation therapy in connection with prostate cancer aggressiveness using the Gleason score, J Urol 178, 1282–8; discussion 1288-9 10.1016/j.juro.2007.05.138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Mostaghel EA, Page ST, Lin DW, Fazli L, Coleman IM, True LD, Knudsen B, Hess DL, Nelson CC, Matsumoto AM, Bremner WJ, Gleave ME and Nelson PS, 2007. Intraprostatic androgens and androgen-regulated gene expression persist after testosterone suppression: therapeutic implications for castration-resistant prostate cancer, Cancer Res 67, 5033–41. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Litman HJ, Bhasin S, Link CL, Araujo AB and McKinlay JB, 2006. Serum androgen levels in black, Hispanic, and white men, J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91, 4326–34. 10.1210/jc.2006-0037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Page ST, Lin DW, Mostaghel EA, Hess DL, True LD, Amory JK, Nelson PS, Matsumoto AM and Bremner WJ, 2006. Persistent intraprostatic androgen concentrations after medical castration in healthy men, J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91, 3850–6. 10.1210/jc.2006-0968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Mohler JL, Gaston KE, Moore DT, Schell MJ, Cohen BL, Weaver C and Petrusz P, 2004. Racial differences in prostate androgen levels in men with clinically localized prostate cancer, J Urol 171, 2277–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Mohler JL, Gregory CW, Ford OH 3rd, Kim D, Weaver CM, Petrusz P, Wilson EM and French FS, 2004. The androgen axis in recurrent prostate cancer, Clin Cancer Res 10, 440–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Godoy A, Montecinos VP, Gray DR, Sotomayor P, Yau JM, Vethanayagam RR, Singh S, Mohler JL and Smith GJ, 2011. Androgen deprivation induces rapid involution and recovery of human prostate vasculature, Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 300, E263–75. 10.1152/ajpendo.00210.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].McKay RR, Werner L, Mostaghel EA, Lis R, Voznesensky O, Zhang Z, Marck BT, Matsumoto AM, Domachevsky L, Zukotynski KA, Bhasin M, Bubley GJ, Montgomery B, Kantoff PW, Balk SP and Taplin ME, 2017. A Phase II Trial of Abiraterone Combined with Dutasteride for Men with Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer, Clin Cancer Res 23, 935–945. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Attard G, Reid AH, Yap TA, Raynaud F, Dowsett M, Settatree S, Barrett M, Parker C, Martins V, Folkerd E, Clark J, Cooper CS, Kaye SB, Dearnaley D, Lee G and de Bono JS, 2008. Phase I clinical trial of a selective inhibitor of CYP17, abiraterone acetate, confirms that castration-resistant prostate cancer commonly remains hormone driven, J Clin Oncol 26, 4563–71. 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.9749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Taplin ME, Montgomery B, Logothetis CJ, Bubley GJ, Richie JP, Dalkin BL, Sanda MG, Davis JW, Loda M, True LD, Troncoso P, Ye H, Lis RT, Marck BT, Matsumoto AM, Balk SP, Mostaghel EA, Penning TM, Nelson PS, Xie W, Jiang Z, Haqq CM, Tamae D, Tran N, Peng W, Kheoh T, Molina A and Kantoff PW, 2014. Intense androgen-deprivation therapy with abiraterone acetate plus leuprolide acetate in patients with localized high-risk prostate cancer: results of a randomized phase II neoadjuvant study, J Clin Oncol 32, 3705–15. 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.4578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.