Abstract

The Center for the Advancement of Pharmacy Education 2013 Affective Domain mandates students develop self-awareness of personal attributes affecting professional growth. Students should self-identify needs, create and implement goals, and evaluate success. This case study describes the qualitative and quantitative findings of an intentional reflection assignment prompting students to engage in a cycle of goal writing – monitoring – reflection – new goal writing, during an immersive clinical practice experience. A blinded review of 144 student assignments is presented in the context of a curricular review of the Reflective Practitioner Program (RPP), a longitudinal reflective thread spanning four years of professional pharmacy training. Evidence gathered in the assignment review indicates that students are sufficiently capable of establishing meaningful goals and describing why the goal is important to their professional development. In contrast, students struggle with articulating strategies for goal achievement and emotions experienced during goal monitoring. In consideration of these findings, RPP faculty identified three major themes when discussing key aspects of the RPP curricular design: 1) students need to articulate strategies for goal achievement in addition to stated aims, 2) students hesitate to identify emotions when reflecting, and 3) reflection needs to be both retrospective and prospective in nature. This case study has resulted in meaningful changes to RPP curricular design and illustrates how programs may approach assessment of the Affective Domain via common curricular elements.

Keywords: Experiential Education, Affective Domain, Reflection

Introduction

The Center for the Advancement of Pharmacy Education (CAPE) released revised educational outcomes in 2013, which introduced the Affective Domain as an essential element of pharmacy education necessary for student development both professionally and personally.1 The affective domain defined students’ self-awareness as an outcome, emphasizing the student’s ability to reflect on one’s personal beliefs, biases, motivations, and emotions. While the affective domain may be a recent addition to pharmacy education standards, the integration of reflective practice into professional development has been established in the health professions education literature, including pharmacy.2–6

The revised CAPE outcomes echo the established philosophy that engaging in critical reflection is important to health care practitioners, who must adapt to a changing work environment while maintaining their individual expertise. Many aspects and terms associated with reflection and reflective practitioners have been offered in the literature.4–5 Evidence suggests reflective practice may improve problem solving skills, critical thinking, professional life-long learning, and possibly reduce errors in judgment and clinical decisions.3, 7 Reflection is also a key aspect of the continuous professional development (CPD) cycle, which has been employed to aid in practitioner development at all levels of pharmacy training.8–10 CPD is often described as a cycle involving reflection or self-appraisal, strategizing for improvement, acting upon one’s plan, and evaluation for change. While reflection may serve many different purposes within pharmacy curricula, the intentional use of reflection for purposes of one’s professional development is needed for fostering lifelong learning skills.11

The University of Colorado Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences (SSPPS) Experiential Education Program has developed and implemented a longitudinal curricular thread, referred to as the Reflective Practitioner Program (RPP), across all four years of the Doctor of Pharmacy program. The RPP includes elements which purposefully cultivate reflective capacity and self-reflection, self-awareness, self-assessment and self-monitoring, goal setting and metacognition and lifelong learning.2, 12–17 The primary aim of the RPP is to reinforce concepts of life-long learning and professional stewardship. Educational methods used in the program include verbal story-telling in the first professional (P1) year, practitioner-mentored small group reflection meetings and written reflections in the subsequent two years (P2-P3 years), purposeful goal writing and goal monitoring in the spring of the third (P3) year, and a capstone reflective assignment during the final professional (P4) year. Students are encouraged early in the RPP to cultivate self-awareness through discussion of professional experiences that are identified as meaningful by the pharmacy student. Mentors are encouraged to coach students to discuss biases, beliefs, motivations, and values. Later in the RPP, students are challenged to think concretely about professional development and life-long learning.

The SSPPS PharmD curriculum has included a structured written reflection component since 2004.18 The RPP built upon this foundation and added elements intended to foster deeper reflection, compliment the writing program, and apply concepts of reflection into practice (Table 1). Students are now introduced to the idea of reflection through a four-hour “Story Slam Workshop,” which is intended to focus on challenges faced by early pharmacy learners. During this workshop, P1 students share an “awkward moment” experienced during an introductory pharmacy practice experience (IPPE). The writing reflection program beginning in the P2 fall semester was restructured to focus more on reflective capacity, rather than demonstration of practice competency. During this component, students remained matched with a consistent reflection peer group and practitioner mentor for three consecutive semesters. Maintaining a consistent peer group and group facilitator across three semesters was intentional, to create familiarity and closeness within the group to better facilitate expression of feelings and emotions within the reflection. Intentional discussions regarding concepts of humility, professionalism, communication, and growth were added as focused content. The mentored elements of the RPP occurring in the third year have shifted in focus towards goal setting in the context of advanced clinical training and practice. Finally, a capstone reflection assignment was integrated into the fourth-year of the program, which allowed students to articulate their successful development throughout their career as a pharmacy student.

Table 1. Overview of the Reflective Practitioner Program Curricular Thread.

| Story Slam P1 Spring | Mentored Reflection P2 Fall – P3 Fall | aIPPE Goals Assignment P3 Spring | Capstone Reflection P4 Spring | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aims | Establish reflective environment through story-telling Introduce and model concepts of reflection |

Cultivate reflective capacity through writing and discussion Assess affective domain |

Apply reflection skills to practice environment | Reflect holistically on professional development Inspire others to reflect |

| Student Expectations | Share first-hand stories on theme of “My most awkward patient encounter.” | 1) Reflect on meaningful practice experiences 2) Strategize for improved future practice |

Engage in cycle of improvement Establish goal, attempt goal, monitor for success, establish new goal |

Share lessons learned with underclassmen Model and reinforce reflective culture to younger peers |

| Faculty Roles | Model reflection Demonstrate vulnerability in sharing experience to peers Coach students to reflect |

Mentor students to engage in critical reflection | (Student self-directed activity) | Acknowledge student’s professional development and growth |

The Advanced Introductory Pharmacy Practice Experience (aIPPE) was selected as a curricular element by which to align the RPP in the spring of the third professional year. The aIPPE is a required six-week full-time clinical rotation designed to prepare P3 students for the rigors of the Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experience (APPE) program and to formally assess students for APPE-readiness.19 Prior to beginning their aIPPE rotation, students are required to write three distinct goals, which are shared with rotation preceptors. Following the rotation experience, students are required to complete a reflection assignment regarding the accomplishment of goals during the rotation.

In parallel to the RPP, SSPPS students received instruction on writing specific, measurable, attainable, realistic, and time-bound (SMART) goals on two different occasions through their didactic curricular sequence prior to the P3 year aIPPE. Purposeful goal writing, and its associated benefits for student achievement, has been discussed within professional education.14, 20 However, it is less clear to what degree students applied principles of effective goal writing to experiential activities. In conjunction with the aIPPE, the RPP prompted students to write goals for an immersive, full-time rotation experience and provided students time to reflect upon their practice experience without immediately beginning a new rotation, as is customary during the APPE year. Thus, the P3 aIPPE reflection assignment represented a point in the student’s training by which many key experiential, didactic, and reflective training converges meaningfully.

Necessity for Case Study

RPP faculty have invested much time and effort in the development of the RPP, and a curricular assessment of its various components was needed to determine the success of the curriculum design, as well as identify next steps of curricular improvement. The primary goal of the RPP was to foster each student’s engagement in life-long learning in ways meaningful to their individual professional development. Internally, anecdotal evidence indicates the RPP has been enjoyed by students, mentors, and faculty. However, it remained unknown if students applied the practices developed in the RPP to their individual professional development in the clinical setting. Thus, a study of the RPP was necessary to: 1) determine if the curriculum achieves its intended purpose and 2) further explore the design of the RPP.

This case study was designed to describe the presence of self-awareness as evidenced by student responses within the goals assignment of the P3 aIPPE course. This assignment was selected because it is the RPP element that most closely resembles professional development within the practice setting. The findings of this case study were intended to be used by RPP faculty to measure success of curricular design for the RPP program and assess effectiveness of the goal writing assignment in particular. To our knowledge, a study to determine if pharmacy students demonstrate self-awareness within their stated goals has yet to be published. The results of this study may determine if additional curricular innovation is necessary to achieve required student outcomes, or if existing and commonly used educational methods (e.g. goal writing) can provide the evidence needed to satisfy accreditation standards. As goal writing may be common in many programs, this represents a practical strategy for programs to assess aspects of the Affective Domain. This case study was reviewed and determined to be non-human research by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board.

Description of Case

Reflective Assignment

Per the aIPPE course assignment instructions, students were required to submit three goals pertinent to their upcoming aIPPE clinical rotation. Goals were made available electronically to rotation preceptors at the start of the rotation and preceptors were encouraged to incorporate goals into the rotation experience as appropriate. Following the completion of the six-week rotation, students completed a post-aIPPE goals reflection assignment (Supplemental File 1). This reflective assignment instructed students to: 1) assess their level of achievement on the three self-determined rotation goals, 2) choose a goal and answer additional reflective prompts about that specific goal, and 3) create a new goal pertaining to their upcoming APPE rotations. Each student was asked to answer the following three reflective questions in regards to their chosen goal: Why is this goal valuable to your readiness to practice pharmacy? What did you do in an effort to achieve this goal? How did you feel during the pursuit of this goal? Both the pre-rotation goal writing assessment and the post-rotation reflective goal assignment were required elements of the aIPPE course. No additional instruction or didactic exposure was provided between the two phases of the reflection assignment.

Assessment of Student Work

For the purpose of this case study, blinded faculty reviewers assessed the three goal statements, the reflective responses to the assigned questions, and the new goal statements. Reviewers assessed text content for evidence of self-awareness of emotions and behaviors using a standardized rubric (Appendix 1). Reviewers rated student statements using a 3-point scale, which described quality of responses as: 0 (below expectations), 1 (meets expectations), and 2 points (exceeds expectations). Meets expectations was defined as being “minimally acceptable” or “good” based on the expectations for the course assignment and elements aligned with the review rubric. Exceeds expectations was warranted when additional depth of detail, reasoning, or explanation was provided by the student.

Three reviewers were trained to use the assessment rubric prior to the study by independently assessing responses from 25 assignments. The primary faculty reviewers included a clinical pharmacy specialist and an industrial-organizational psychologist, neither of whom had teaching responsibilities within the RPP. The third reviewer was a clinical faculty member responsible for developing several of the RPP curricular elements. The reviewers discussed their assessments to normalize scoring methods, ensure shared understanding of the assessment tool and achieve consensus regarding definitions of each performance rank of the rubric. All student assignments (n=144) were then assessed independently by the two primary reviewers. In the case of disagreement, the third reviewer assessed the assignment and determined final scoring.

The aIPPE goal assignments were submitted online using the E*Value™ (MedHub, Inc., Minneapolis, MN) online educational portfolio system. De-identified data presented in a random order were provided to the reviewers using Microsoft® Excel® 2016 (Microsoft Corp., Santa Rosa, CA) files. Reviewers’ scores were analyzed using IBM® SPSS® Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Tests were used for comparison of scores between original and new goal statements.

Evaluation of Student Learning

The rates of agreement between faculty reviewers during the training phase were 88% (quality of goal writing – selected goal), 90% (description of goal’s importance to practice), 92% (description of strategy to achieve goal), and 93% (quality of goal writing – new goal). Assignments from 144 students (98% of students initially enrolled in the aIPPE course) were available for review at the time of the study. Examples illustrating the breadth of student goals and reflective statements and their associated faculty ratings are provided in Table 2. Students described 432 unique rotation goals within the assignment. Students most frequently reported goals as either fully achieved (58.3%) or partially achieved (35%). Only nine goals (2%) were identified as not attempted during the rotation. When asked to select a goal for further reflection, 95% of students choose a goal that was either partially or fully achieved with seven students selecting an attempted but failed goal (Figure 1).

Table 2. Examples of Student Goals and Reflective Responses.

| Student # | What is your aIPPE goal? (Description Score; Strategy Score) | Why is this goal valuable to your readiness to practice pharmacy? (Description Quality Score; Connection to Profession Score) | What did you do in an effort to achieve this goal? (Description Effort Score) | How did you feel during the pursuit of this goal? (Emotional Description Score; Connection of Emotion to Practice Score) | Please describe one goal for your own professional development you wish to achieve prior to beginning your P4 APPE rotations. (Description Score; Strategy Score) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 57 | “Enhance my interviewing skills.” (1; 0) | “Communication between patients is something a pharmacists does on a daily basis. Getting better at patient interviews is a key component to communication.” (1;1) | “I interviewed or interacted with at least 1 patient a day to get more practice at patient interviewing.” (2) | “I always liked communicating with people. However, asking the right question is not always easy. Therefore, I feel that I got better at asking the right questions and being more comfortable asking them.” (1;2) | “Be a more confident presenter to health care providers and peers. One way I can do this is by practicing with other students and participating more in class.” (2;2) |

| 76 | “Be exposed to as much as possible.” (0; 0) | “Wider knowledge base.” (0) | “Took on any and all projects” (0) | “Good” (0) | “Know as much as I can, and do the best job possible.” (1; 0) |

| 131 | “To improve on my patient communication skills” (1; 0) | “So I can better and effectively communicate with patients.” (1;1) | “I was proactive.” (0) | “Felt Accomplished” (1; 0) | “Communications” (0; 0) |

Figure 1. Student reported level of goal achievement for all goals (n=432) and selected goals (n-144) used in the reflection assignment.

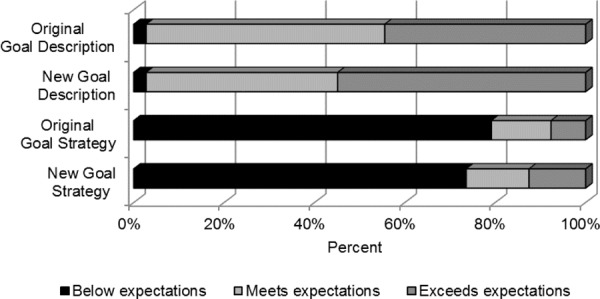

Based on the faculty reviewers’ evaluations of each student’s selected goal, students demonstrated a clear ability to describe goals well (97.2% receiving ratings of 1 or 2), but students often failed to include strategies for achieving each goal in their written statements (20.8% receiving ratings of 1 or 2). This pattern was also observed with the students’ written statement for their new APPE goal (Figure 2). When comparing acceptable ratings between the original goal statement and the new goal written for future rotations, students demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in quality of goal description (p = 0.047). A smaller rate of improvement was observed in regards to the inclusion of a goal achievement strategy compared with the original goal, as illustrated by student 57 in Table 2, but this was not statistically significant (p = 0.185).

Figure 2. Reviewer ratings of writing quality of original new goals.

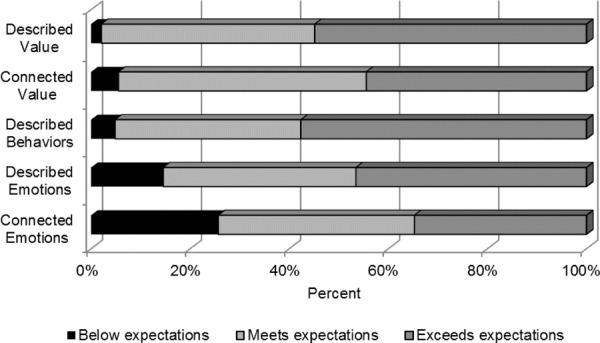

When looking at the a priori goals for evidence of emotions and behaviors (Figure 3), reviewers identified evidence of describing value (why a goal is important) and connecting value (why the goal is important to one’s professional development or professional ambitions) with rates of 97.9% and 94.4%, respectively. When describing attempts to achieve the target goal, students were often able to describe specific actions and behaviors taken to achieve their aim (95.1%). Fewer students described emotions felt while attempting to achieve their goal (85.4%), or connected their described emotion to the context of their goal or experience (74.3%).

Figure 3. Elements of self-awareness within student’s selected goal.

Case Themes

RPP Faculty and reviewers met as a group once the analysis of data became available. The group was asked to reflect upon their perceptions of the findings in context of the larger RPP curricular thread. Discussion was led by the lead investigator using a simple debrief format framed by two questions: What is the RPP doing well? and What should be improved?; otherwise, the discussion was unstructured to allow for all perspectives to be heard. The group was asked to identify themes and hypotheses regarding the value and design of the RPP, which could result in curricular improvement. Three key themes emerged, which may influence the RPP in subsequent cohorts of students, as well as future directions for research. The lead investigator summarized themes and each contributor reviewed statements prior to publication.

Theme 1. Students need strategies in addition to aims when establishing goals

Strategizing the process for improving oneself through abstract conceptualization is a critical aspect of the life-long learning cycle and may be inferred as an expected outcome within the self-awareness domain of the CAPE outcomes.1 Despite receiving instruction regarding the use of the SMART goal framework for strategizing goal achievement at multiple time-points within the curriculum, students did not routinely adopt this framework when writing their goal statements. Reviewers felt students were successful in determining applicable goals, as well as demonstrating many aspects of self-awareness in their goal writing; however, not all students were able to articulate how one would achieve the stated goal. It is unclear if students struggled in strategizing how to achieve a chosen goal or if they simply struggled with articulating their strategy when writing their goal.

Since SMART goal writing is a component within the pharmacy curriculum, it was assumed that students would utilize this strategy when formulating their goals. In reviewing the original goal assignment, it became evident that the format of the SMART goal was not required or explicitly requested by the assignment instructions. Thus, the results of the case study should be understood in the context of what a student would do if simply given the instructions “write three goals,” which may not be generalizable to all experiential settings. Unfortunately, formal assessment of SMART goal framework was not conducted, thus many questions remain. For example, RPP faculty are curious if students who earned higher marks in strategizing their goal employed the SMART goal writing strategy. Perhaps use of the SMART goal structure would have improved the student’s ability to articulate strategies for goal achievement. Collaboration with non-experiential faculty who provide SMART goal instruction within the curriculum may be needed to better align goal writing with experiential education.

Theme 2. Students hesitate to identify emotions when reflecting

Tending to emotions in reflective writing is a key element indicating reflective capacity.2 A hesitation to directly address or describe emotions experienced during goal achievement in this case study was identified by faculty reviewers and is evident by lower scores in describing and connecting emotions in contrast to describing behaviors and values. For example, students described the lack of opportunity to attempt a goal during the rotation, but would not go so far as describing the feelings of disappointment or frustration one would expect in such a situation. Similarly, expected sentiments of excitement, pride, or feelings of accomplishment were frequently not expressed when discussing achieved goals.

In early curricular components of the RPP, students often discuss emotionally charged and meaningful professional encounters. Through discussions with RPP faculty, we recognized that emotions are often present within the reflection assignments and particularly during group discussions, however the emotions themselves may not be identified or labeled directly by the student. During the case-study debrief session, faculty pondered if they themselves avoid pushing students to articulate or recognize their emotions. Should faculty prompt the student to identify the emotions they are experiencing directly, or is it enough to simply assume the student recognizes the emotions being expressed as perceived by the faculty member? The group achieved consensus that tending to one’s emotions should be a more intentional aspect of the RPP as the group perceived the value of emotional intelligence and self-awareness has been increasing within health profession education and practice.

The importance of disseminating these findings to all RPP faculty mentors was recognized, and those discussions helped identify changes. As a result of this case study, RPP faculty mentors are now encouraged to push students to articulate their feelings and emotions in both group reflection meetings and in writing. RPP faculty are also encouraged to model this in their own behavior during reflection, as well as reinforce emotional awareness, when providing feedback to students. It is hoped that making this an intentional focus of practitioner mentor training may further improve curricular effectiveness of the RPP.

Theme 3. Reflection needs to be both retrospective and prospective

Throughout the RPP, the Kolb learning cycle is often referenced, when discussing the value of reflection on improving one’s professional skills.20 Evidence collected in this case study supports the hypothesis that students can improve their ability to strategize after reflection, as suggested by the Kolb learning cycle. Reviewers noted and documented improvement in goal writing, when comparing students’ new goal written immediately following the reflection exercise to the goals written prior to the start of the rotation. The improvement in goal quality occurred without receipt of any additional instruction, thus it may be hypothesized that requiring both retrospective and prospective reflection within the same activity resulted in a better student product.

While it may be common for students to engage in prospective goal setting at the start of a new clinical rotation experience, faculty question if retrospective reflection occurs at the end of each rotation. The perceived value of reflecting on past experience before strategizing for future performance aligns with the philosophy of the SSPPS experiential sequence. The first immersive clinical experience, the aIPPE, concludes several months before the student’s initial advanced pharmacy practice experience rotation. By structuring this assignment to end with writing a new goal, faculty anticipated students would internalize this cycle of goal setting, goal monitoring, reflection, and establishing new goals between each rotation. During the case study debrief, the group achieved consensus that the aIPPE reflection assignment was well-sequenced within the RPP and optimized the time available to the student for retrospective reflection. This was viewed as a strength of the RPP which could not be achieved as well by placing the assignment between APPE rotations occurring in quick secession.

The strategy of reflecting upon past events and then anticipating future strategies for improvement has been integrated elsewhere in the RPP. During the second-year mentored reflective writing program, students are instructed to reflect upon a meaningful experience through three distinct lenses: The Narrative (What happened?), The Reflection (What does this experience reflect about me?), and The Change (How will this change my practice?). While students engaged in meaningful reflection prior to the adoption of this structure, these lenses helped highlight important aspects of reflection as students began articulating concrete changes into their reflective writing indicating how their perspectives have changed, how they will strategize to improve, and/or how they will approach similar experiences differently in the future. RPP faculty have found the section devoted to change as the richest in terms of identifying professional growth and self-improvement. Faculty identified the consistent use of retrospective and prospective reflection to be a strength of the RPP curricular design.

Case Study Implications

The lasting impact of the RPP curricular elements may be difficult to assess, therefore this study provides a concrete assessment of the RPP in an applied manner. The evidence of successful RPP curricular design provided by this case study should be viewed in the context of other data evaluating students’ ability to reflect and engage in life-long learning. RPP faculty felt the P3 aIPPE assignment was a meaningful addition to the RPP program and it has remained in place.

Many subtle changes have been implemented within the RPP program as a result of this case study. For example, RPP faculty intentionally discuss emotional awareness with new practitioner mentors. Furthermore, RPP faculty intentionally model reflection and tending to emotions when sharing personal stories as part of the P1 Story Slam and during small group reflection meetings. A twenty-minute workshop on writing SMART goals for the aIPPE was added at the start of the third year to reinforce prior didactic content on the subject, as well as emphasize the importance of identify the steps needed to achieve goals. Themes of reflection writing in the third year have been modified and expanded to include SMART goal writing with feedback provided by practitioner mentors. Faculty anticipate that these small but meaningful changes reinforce the concepts of self-awareness, as well as life-long learning.

Faculty felt there were aspects of this case study generalizable to all schools of pharmacy. To our knowledge, rotation goals have not been evaluated for evidence of self-awareness in the context of reflective capacity within the pharmacy literature. We hypothesized that pharmacy students are commonly asked to establish goals for rotations by preceptors, and that this may occur even if not explicitly directed to do so. We are less certain, however, that students are directed to articulate goals in writing and intentionally reflect upon their goal achievement upon the conclusion of their rotation. As schools of pharmacy are challenged to assess the affective domain, this case study illustrates a simple assignment design, which could be applied in existing experiential education programs.

Conclusion

Students reported success at achieving pre-rotation goals during an immersive clinical training experience. Using a guided reflection upon completion of the rotation created opportunities for students to reflect upon their goals, as well as provided evidence of self-awareness. Students tended to fully describe goals and their associated values, yet struggle to equally describe the strategies needed to achieve goals and are less likely to directly address or label emotions when reflecting upon goal achievement. Upon completing a cycle of goal writing – application – reflection – new goal writing, the quality of goal writing for future experiences improves, indicating that the student is capable of applying principles of lifelong learning. However, it is not clear if this improvement in goal writing is sustained over time.

This case study identified both elements of successful curricular design, as well as areas for needed improvement at our institution. Future studies are needed to determine effectiveness of all RPP elements and to document evidence of student learning throughout the reflection curriculum. It is unknown to what extent students employ life-long learning strategies into their own practice or how much instruction and experience is needed before students adopt these strategies. Many unknowns remain regarding which elements of a pharmacy curriculum increase student success in achieving the outcomes of the affective domain.

Appendix 1. Post-aIPPE Goal Reflection: Faculty Rubric

Please rate each student’s response to the assignment question below using the following scale

0 = Question not answered, or not enough details or evidence provided

1 = Answered question with minimal depth or details

2 = Answered with detailed or in-depth response

| Student’s Question: Using one or two sentences, please list the goals you identified prior to the start of the aIPPE rotation. | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| Response describes WHAT is wanted to be achieved (e.g. goal is clearly articulated and outcome is measurable) | □ | □ | □ | |

| Response describes HOW it will be achieved (e.g. response provides a specific plan of action, timeframe for completion, resources needed for success, etc) | □ | □ | □ | |

| Student’s Question: Why is this goal valuable to your readiness to practice pharmacy? | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| Quality of response (depth, level of detail) (e.g. response describes importance of goal to self and/or one’s self-improvement) | □ | □ | □ | |

| Response connects goal to value to the profession of pharmacy (e.g. response articulate how goal will assist in development as a pharmacy professional) | □ | □ | □ | |

| Student’s Question: What did you do in an effort to achieve this goal? | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| Response describes specific behaviors (e.g. describes concrete actions taken in order to attempt or achieve goal) | □ | □ | □ | |

| Student’s Question: How did you feel during the pursuit of this goal? | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| Response describes emotion | □ | □ | □ | |

| Response connects emotion to goal and/or experience (e.g. describes emotion in context of goal attempt or achievement, or as a response to specific experience) | □ | □ | □ | |

| Student’s Question: Please describe one goal for your own professional development you wish to achieve prior to beginning your P4 APPE rotations. | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| Goal describes WHAT is wanted to be achieved (e.g., goal is clearly articulated and outcome is measurable) | □ | □ | □ | |

| Goal describes HOW it will be achieved (e.g. response provides a specific plan of action, timeframe for completion, resources needed for success) | □ | □ | □ | |

Supplemental File 1. Post-aIPPE Goal Reflection Student Assignment

| Using one or two sentences, please list the goals you determined prior to starting the aIPPE rotation. | |

| Goal A | |

| Goal B | |

| Goal C | |

| For each goal, please indicate how well you accomplished these goals during your aIPPE rotation. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goal | Fully achieved | Partially achieved | Attempted, but not achieved | Not attempted |

| A | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| B | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| C | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| Select one of the above goals that you either attempted or achieved. Then use that selected goal to answer the questions below. | |

| Indicate which goal you have selected. |

□ Goal A □ Goal B □ Goal C |

| Using the selected goal from above, answer the following questions using no more than 4 sentences per response. | |

| Why is this goal valuable to your readiness to practice pharmacy? | |

| What did you do in an effort to achieve this goal? | |

| How did you feel during the pursuit of this goal? | |

| Using no more than 4 sentences, please describe one goal for your own professional development you wish to achieve prior to beginning your P4 APPE rotations. |

Financial Disclosures

None

Conflicts of Interest

None

References

- 1.Medina MS, Plaza CM, Stowe CD, et al. Center for the Advancement of Pharmacy Education (CAPE) Education Outcomes. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;2013;77(8) doi: 10.5688/ajpe778162. Article 162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wald HS, Borkan JM, Taylor JS, Anthony D, Reis SP. Fostering and evaluating reflective capacity in medical Education: Developing the REFLECT rubric for assessing reflective writing. Acad Med. 2012;87(1):41–50. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31823b55fa. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31823b55fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsingos-Lucas C, Bosnic-Anticevich S, Schneider CR, Smith L. Using reflective writing as a predictor of academic success in different assessment formats. Am J Pharm Educ. 2017;81(1) doi: 10.5688/ajpe8118. Article 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsingos C, Bosnic-Anticevich S, Smith L. Reflective Practice and its implications for pharmacy education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014;78(1) doi: 10.5688/ajpe78118. Article 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wallman A, Kettis Lindbald A, Hall S, Lundmark A, Ring L. A categorization scheme for assessing pharmacy students’ levels of reflection during internships. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(1) doi: 10.5688/aj720105. Article 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Embo MPC, Driessen E, Valcke M, Van Der Vleuten CPM. Scaffolding reflective learning in clinical practice: A comparison of two types of reflective activities. Med Teach. 2014;36(7):602–607. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2014.899686. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2014.899686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mamede S, Schmidt H, Penaforte JC. Effects of reflective practice on the accuracy of medical diagnoses. Med Educ. 2008;42:468–475. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03030.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Austin Z, Marini A, Macleod Glover N, Croteau D. Continuous professional development: A qualitative study of pharmacists’ attitudes, behaviors, and preferences in Ontario, Canada. Am J Pharm Educ. 2005;69(1) Article 4. [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Brocta R, Abu-Baker A, Budukh P, Gandhi M, Lavigne J, Birnie C. A continuous professional development process for first-year pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;76(2) doi: 10.5688/ajpe76229. Article 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McConnell K, Delate T, Newlon CL. The sustainability of improvements from continuing professional development in pharmacy practice and learning behaviors. Am J Pharm Educ. 2015;79(3) doi: 10.5688/ajpe79336. Article 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Janke KK, Tofade T. Making a curricular commitment to continuing professional development in Doctor of Pharmacy programs. Am J Pharm Educ. 2015;79(8) doi: 10.5688/ajpe798112. Article 112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benbassat J, Baumal R. Enhancing self-awareness in medical students: An overview of teaching approaches. Acad Med. 2005;80(2):156–161. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200502000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Epstein RM, Siegel DJ, Siberman J. Self-monitoring in clinical practice: A challenge for medical educators. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2008;28(1):5–13. doi: 10.1002/chp.149. doi: 10.1002/chp.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Motycka CA, Rose RL, Ried D, Brazeau G. Self-assessment in pharmacy and health science education and professional practice. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(5) doi: 10.5688/aj740585. Article 85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Harthy I, Was CA. Goals, Efficacy and metacognitive self-regulation: A path analysis. Int J Educ. 2010;2(1):E2. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coutinho SA. The Relationship between goals, metacognition, and academic success. Educate. 2007;7(1):39–47. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schunk DH. Goal setting and self-efficacy during self-regulated learning. Educ Psychol. 1990;25(1):75–86. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nuffer W, Vaughn J, Keer K, et al. A three-year reflective writing program as part of introductory pharmacy practice experiences. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(5) doi: 10.5688/ajpe775100. Article 100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilliam E, Nuffer W, Thompson M, Vande Griend J. Design and activity evaluation of an Advanced-Introductory Pharmacy Practice Experience (aIPPE) course for assessment of student APPE-readiness. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2017;9(4):595–605. doi: 10.1016/j.cptl.2017.03.028. doi: 10.1016/j.cptl.2017.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alrakaf S, Sainsbury E, Grenville R, Smith L. Identify achievement goals and their relationship to academic achievement in undergraduate pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014;78(7) doi: 10.5688/ajpe787133. Article 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kolb DA. Vol. 1. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1984. Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. [DOI] [Google Scholar]