Abstract

Collaborative care has been widely recognized as being critical to promoting the health of individuals and populations. It is hypothesized that the development of partnerships between community-based organizations and community pharmacies may result in increased access to preventive care services for community members with the goal of improving health outcomes. The purpose of this review was to identify and describe partnerships between community-based organizations and community pharmacies. A literature search was conducted for all articles in the English language published through January 2018 that included these types of partnerships offering preventive care services. A total of seven articles were included in the review, of which the majority were conducted in the United States (n=5). Community-based organizations included businesses, community health centers, local associations, public health departments, schools, and workplaces. Preventive care services that were offered included blood pressure and cardiovascular risk assessment, diabetes management, flu ready card and HIV self-test kit voucher distribution and education, and bone mineral density screenings. The limited literature suggests that additional opportunities should be explored in order for community-based organizations and community pharmacies to partner in order to provide and evaluate the impact of preventive care services in the community setting.

Keywords: community based organizations, pharmacies, community pharmacy, prevention

Introduction

Collaborative care has been widely recognized as being critical to promoting the health of individuals and populations.1 Interprofessional collaborative practice occurs when health workers from different disciplines work with patients, families, and communities to provide safe, high-quality, accessible, patient-centered care.2, 3 This is expected to promote the triple aims of the patient care experience, health of populations, and reducing cost.3

Patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs) have developed over the past fifty years as a tool for providing comprehensive and coordinated patient care.4–8 More recently, medical neighborhoods have gained recognition as a strategy to ensure that patients receive appropriate services that extend beyond the traditional PCMH, which continues to serve as the central point of coordination and continues to focus on providing patient-centered care.1 Medical neighborhoods include the PCMH; health service organizations such as community pharmacies (CP), diagnostic laboratories, and rehabilitation facilities; and community-based organizations (CBO) which are public or private nonprofit organizations that are representative of the community and engaged in meeting community needs. Examples of CBOs that have provided health-related services include faith-based organizations, public health departments, schools, and senior residential centers.9–19 Through medical neighborhoods, patients are able to receive high quality, individualized care from a variety of people with multiple expertise.

One type of health service organization that has historically been overlooked is CPs. CPs are highly accessible locations for many community members as evidence by approximately 94% of people in the United States live within 5 miles of a CP, frequent evening and weekend hours, and no need for an appointment for many services.20, 21 Furthermore, pharmacists are highly trained healthcare professionals who can provide a broad range of services such as dispensing medications, administering vaccines, conducting comprehensive medication reviews, and point-of-care testing for diseases. In order to maximize their benefit in the community, it may be useful for CPs to partner with CBOs as they typically have more connections with the local community and this may result in penetration of preventive services among community members including those who may not have routine access to traditional health care services. The purpose of this review was to identify and describe partnerships between CBOs and CPs.

Methods

Information sources used in the search for studies to include in this review were PubMed, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Scopus, and Educational Resources Information Center (ERC) via ProQuest through Taubman Health Sciences Library at the University of Michigan Ann Arbor to conduct a systematic review of the literature. Articles were included if they were published through December 2017. The search strategy conducted in each database included search terms and relevant controlled vocabulary for two concepts: CP and CBO. Articles populated from PubMed, CINAHL Scopus, and ERIC via ProQuest were 429, 131, 796, and 16, respectively (Table 1). After removing duplicate citations, the search strategies retrieved 775 titles and abstracts for review. Studies were included if they reflected the partnership of CBOs and CPs. No reports were used and no data obtained from investigators.

Table 1. Search Strategy.

| PubMed | 2/6/2018 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Concept | # | Search Strategy | Results |

| Community pharmacy | 1 | “Community Pharmacy Services” [Mesh] OR “community pharmacy” [tiab] OR “community pharmacies” [tiab] OR “community pharmacist” [tiab] OR “community pharmacists” [tiab] OR (“community-based” [tiab] AND (pharmacy[tiab] OR pharmacies[tiab] OR pharmacist[tiab] OR pharmacists[tiab])) | 7027 |

| Community organization | 2 | (“community-based” [tiab] AND (organization[tiab] OR organizations[tiab] OR center[tiab] OR centers[tiab])) OR CBO OR “religious center”[tiab] OR “religious centers” [tiab] OR church[tiab] OR churches[tiab] OR temple[tiab] OR temples[tiab] OR synagogue[tiab] OR synagogues[tiab] OR mosque[tiab] OR mosques[tiab] OR “senior center” [tiab] OR “senior centers” [tiab] OR “community center” [tiab] OR “community centers” [tiab] OR school[tiab] OR schools[tiab] OR “health department” [tiab] OR “health departments” [tiab] OR “Senior Centers” [Mesh] OR “Schools” [Mesh] | 311675 |

| Combined | 3 | 1 AND 2 | 429 |

| CINAHL | 2/6/2018 | ||

| Concept | # | Search Strategy | Results |

| Community pharmacy | 1 | (MH “Community Health Services+” AND MH “Pharmacy Service”) OR TI(“community pharmacy” OR “community pharmacies” OR “community pharmacist” OR “community pharmacists” OR (“community-based” AND (pharmacy OR pharmacies OR pharmacist OR pharmacists))) OR AB(“community pharmacy” OR “community pharmacies” OR “community pharmacist” OR “community pharmacists” OR (“community-based” AND (pharmacy OR pharmacies OR pharmacist OR pharmacists))) | 3333 |

| Community organization | 2 | TI((“community-based” AND (organization OR organizations OR center OR centers)) OR CBO OR “religious center” OR “religious centers” OR church OR churches OR temple OR temples OR synagogue OR synagogues OR mosque OR mosques OR “senior center” OR “senior centers” OR “community center” OR “community centers” OR school OR schools OR “health department” OR “health departments”) OR AB((“community-based” AND (organization OR organizations OR center OR centers)) OR CBO OR “religious center” OR “religious centers” OR church OR churches OR temple OR temples OR synagogue OR synagogues OR mosque OR mosques OR “senior center” OR “senior centers” OR “community center” OR “community centers” OR school OR schools OR “health department” OR “health departments”) OR MH “Senior Centers” OR MH “Schools+” | 148165 |

| Combined | 3 | 1 AND 2 | 131 |

| Scopus | 2/6/2018 | ||

| Concept | # | Search Strategy | Results |

| Community pharmacy | 1 | TITLE-ABS-KEY(“community pharmacy” OR “community pharmacies” OR “community pharmacist” OR “community pharmacists” OR (“community-based” AND (pharmacy OR pharmacies OR pharmacist OR pharmacists)) | 10108 |

| Community organization | 2 | TITLE-ABS-KEY((“community-based” AND (organization OR organizations OR center OR centers)) OR CBO OR “religious center” OR “religious centers” OR church OR churches OR temple OR temples OR synagogue OR synagogues OR mosque OR mosques OR “senior center” OR “senior centers” OR “community center” OR “community centers” OR school OR schools OR “health department” OR “health departments”) | 1093246 |

| Combined | 3 | 1 AND 2 | 696 |

| ERIC via ProQuest | 2/6/2018 | ||

| Concept | # | Search Strategy | Results |

| Community pharmacy | 1 | (MAINSUBJECT.EXACT.EXPLODE(“Community Health Services”) AND MAINSUBJECT.EXACT.EXPLODE(“Pharmacy”)) OR TI(“community pharmacy” OR “community pharmacies” OR “community pharmacist” OR “community pharmacists” OR (“community-based” AND (pharmacy OR pharmacies OR pharmacist OR pharmacists))) OR AB(“ommunity pharmacy” OR “community pharmacies” OR “community pharmacist” OR “community pharmacists” OR (“community-based” AND (pharmacy OR pharmacies OR pharmacist OR pharmacists))) | 77 |

| Community organization | 2 | TI((“community-based” AND (organization OR organizations OR center OR centers)) OR CBO OR “religious center” OR “religious centers” OR church OR churches OR temple OR temples OR synagogue OR synagogues OR mosque OR mosques OR “senior center” OR “senior centers” OR “community center” OR “community centers” OR school OR schools OR “health department” OR “health departments”) OR AB((“community-based” AND (organization OR organizations OR center OR centers)) OR CBO OR “religious center” OR “religious centers” OR church OR churches OR temple OR temples OR synagogue OR synagogues OR mosque OR mosques OR “senior center” OR “senior centers” OR “community center” OR “community centers” OR school OR schools OR “health department” OR “health departments”) OR MAINSUBJECT.EXACT.EXPLODE(“Schools”) | 583623 |

| Combined | 3 | 1 AND 2 | 16 |

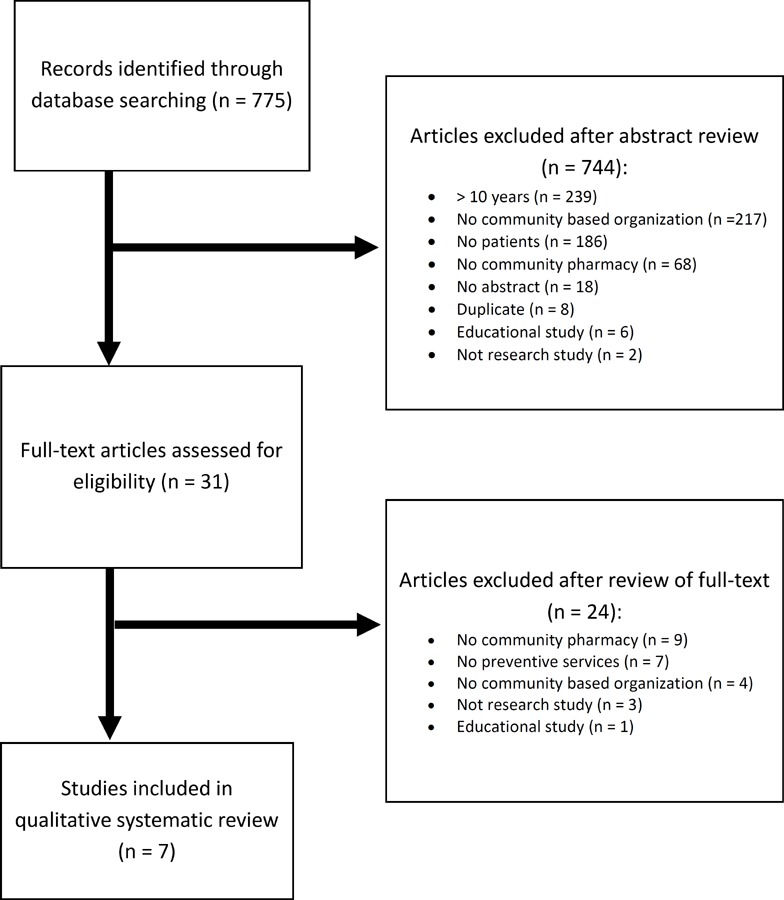

During the abstract review, studies were included if they were published from 2007 to 2017, had an abstract available, were in English, reflected the partnership of CBOs and CP, included the provision of preventive services, and did not focus on educational research. A total of 744 articles were excluded. A data abstraction form to collect information related to the location, patient population, type of community partner, intervention/service provided, results, and limitations was created. Two team members were trained to gather data and the results were discussed with a third team member until consensus was reached. A full review of 31 articles was conducted and a total of 7 articles met all inclusion criteria (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Article retrieval and review.

Results/ Findings

Data related to population, partners, intervention, findings, and limitations organized by level of interprofessional practice were described (Table 2). Five studies were conducted in the United States and the remaining two were in Australia and Spain, respectively. Most involved loosely organized networks (n=3) which aimed to increase access to services, such as by distribution of vouchers or coordination of care between different healthcare professionals and settings (n=3) and the remaining study involved directed collaboration between different health care disciplines.

Table 2. Summary of partnership between community pharmacies and community-based organizations by level of interprofessional practice.

| Study | Population | Partnersa | Intervention | Findings | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Networking | |||||

| Rosenf eld LA et al. 201122 | Chain Pharmacy Customers in Palm Beach, Florida |

|

Flu ready cards distributed, and influenza doses shipped to local pharmacies and retail health clinics to administer to members of the community |

|

|

| Marlin RW et al. 201423 | Adult, African American, sexually active, homosexual males in Los Angeles, California | – 3 local CBOs | HIV self-test kit vouchers ($1) distributed by CBO and redeemed at Walgreens’ Pharmacies |

|

|

| Meyer son BE et al. 201624 | African American men and women in Indianapolis, within the distributor’s social and professional network | African American HIV Action Team (AHIT): a coalition of 4 CBOs, Walgreens pharmacies, a school of public health | Distributors handed out HIV vouchers to people in their professional and social circles for redemption of a HIV test kit at one of three Walgreens Pharmacies |

|

|

| Coordination | |||||

| Cadilh ac DA et al. 201525 | Adults in Australia |

|

Free blood pressure assessment and education about blood pressure and strokes; generic referral sent to physician if blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg; assessment of retention of knowledge of risk factors and health conditions associated with high blood pressure |

|

|

| Weidl e PJ et al. 201426 | Patients from urban and rural pharmacies across the United States |

|

Point-of-care HIV testing at community pharmacies and retail clinics; provided confidential results and information on HIV; referred to physician or health department for confirmatory testing and HIV care, if needed |

|

|

| Harris AC et al. 201127 | Women 21 years and older, in Iowa City, Iowa |

|

Bone mineral density screenings, education, and medical referrals if appropriate |

|

|

| Collaboration | |||||

| Segura A et al. 200728 | Patients living in a low economic neighborhood in Barcelona, Spain |

|

Patient care teams developed a program for monitoring diabetic and hypertensive patients in the local pharmacies |

|

|

Community pharmacies were partners in all studies

A diverse group of patients benefited from the services, ranging from young children to the elderly, rural and urban communities, and range of socioeconomic status levels. The studies illustrated multiple CP/CBO partnerships including family physician practices, local public health departments, local schools and businesses, community health centers, and independent living facilities. Unique services/interventions offered in the different studies included blood pressure (BP) and cardiovascular (CV) risk assessment, diabetes management, flu ready card and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) self-test kit voucher distribution and education, influenza vaccine administration and education, bone mineral density screening, and general medication errors and management.

Discussion

With the ongoing evolution of healthcare, capable of being delivered interprofessionally through multiple different settings via people with diverse backgrounds, resources and personnel within these settings should be utilized to their maximum capacity and potential to assist in providing optimal care to community members. Areas where this collaboration has been successful include CPs, family physician offices, retail health clinics, community health centers, local public health departments, local schools, local businesses, local clubs, local associations, and workplaces. Branching services out into the community allows for the opportunity to reach people beyond the CP or doctor’s office and enables those community members to remain in a comfortable environment, possibly contributing to more open mindedness and willingness to accept and engage in preventive services and understanding through education. These partnerships can potentially contribute to improved interprofessional coordination and collaboration of care between healthcare providers. The remaining discussion uses the literature that was identified through the systematic review to provide examples of networking, coordination, and collaboration.

Networking

Networking is a defined as a loose relationship between a CP and a CBO that provides education and resources for patients to access preventative services. Each of the three studies with a networking model distributed cards or vouchers for redemption at a local CP. Marlin RW et al. 2014 and Meyerson BE et al. 2016 provided vouchers for at-home HIV testing kits while Rosenfeld LA et al. 2011 distributed cards for influenza vaccinations.22–24 Rosenfeld LA et al. 2011 focused on pharmacy customers in Palm Beach, Florida while Marlin RW et al. 2014 and Meyerson BE et al. 2016 focused on specific patient populations including adult, African American, sexually active homosexual males in Los Angeles, California and African American men and women in Indianapolis, Indiana, respectively.22–24

Rosenfeld LA et al. 2011 provided an opportunity for pharmacists to provide education and vaccinations to people in the Palm Beach area as part of a H1N1 influenza vaccination campaign.22 Pharmacists reported that 90% of patients asked about receiving flu shots and influenza prevention recommendations. Pharmacists were able to play a vital role in administering vaccines, serving as a link to other health care professionals, and strengthening the preparedness of the community in responding to flu pandemics. In studies distributing HIV vouchers, 14.9% and 18.2% were redeemed.23, 24 Both studies found patients appreciated the privacy and confidentiality of the voucher system, with one reporting a 78% satisfaction rate (Marlin).23 This non-targeted method of distributing vouchers was a tactic used to destigmatize HIV testing.

CPs provide a critical avenue for the general population to access care. Providing the community with the tools necessary to obtain care makes it easier for patients to take the first step. These studies highlight the importance of pharmacists located in these settings not only on educating patients, but also on decreasing the stigma of seeking care and extending the reach of health care professionals. These articles were limited in the populations they represented and most of the studies did not evaluate the clinical outcomes of the services to assess their effectiveness or patient satisfaction. Due to this, we can only quantify the number of people who redeemed the vouchers, not the impact of the vouchers in preventative services.

Coordination

The coordination model was defined as a referral to another health care professional for any patients who had abnormal test results. Of the studies, three used this model for blood pressure, HIV screening, and bone mineral density screening. Harris et al. 2001 found 19.4% (n=62) of patients were at increased risk of bone fracture upon initial screening, and were referred to a physician for follow up.27 Weidle et al. 2014 was able to refer 1.6% (n=24) of patients who tested positive for HIV at a screening in CPs.26 Lastly, Cadilhac et al. 2015 was able to identify over 50,000 patients with elevated blood pressure, and referred them to follow up with a physician for further treatment.25 Of the three studies, only Cadilhac et al. 2015 followed up with patients to see if they acted on their referral, and found 80% had an appointment with their doctor within three months of the initial screening.25 Coordination models allow for the pharmacist to provide screening and to educate the patient along with a plan to support appropriate follow up. All three studies were able to identify patients who were unaware of their condition, and created the opportunity for them to seek treatment. A key limitation with this model is that pharmacists are unable to diagnose the patient based on the results of preliminary screenings. A physician must be seen for diagnosis and treatment. None of the studies assessed the cost of implementing these services, and therefore we are unable to determine the financial consequences. And lastly, the impact these screenings had on pharmacy workflow and staffing were not addressed.

Collaboration

Collaboration models build off the coordination model in that they have a specific physician or patient care team to help treat the patient if abnormal results are identified. These health care professionals work in conjunction with the pharmacist or pharmacy involved in the CBO relationship. Only one study followed this model.28 The study performed blood pressure screenings and diabetes management for patients in Barcelona, Spain. While the study did receive good reviews from patients who appreciated the convenience and accessibility of having these services at their local pharmacies, the study did not quantify their results or assess the impact of the pharmacists’ individual roles.

Development and implementation of services

Strategies can be implemented to assist in developing the CP and CBO partnerships. It is important to identify champions at the CP and CBO, a communication strategy, a target population, an intervention, and an assessment strategy. Champions at the CP and CBO must communicate effectively in order to design, implement, and evaluate the intervention. It is important to recognize that the culture related to communication may vary between organizations (e.g., email, face-to-face meetings, conference calls). Some strategies to identify patients in need include conducting surveys or sending letters to community members to determine the interest or need via the community perspective, running pharmacy reports to determine large patient populations with a particular disease state or on a particular medication or class of medications, or conducting or utilizing an existing community needs assessment. Care should be taken to learn about services and interventions that exist in a community before implementing a new program in order to ensure that there is a need. The target population, disease state, and resources at the CP and CBO should be considered when determining whether to set up a network, coordination, or collaboration. Finally, based on the findings in this literature review, there is a lack of data available related to patient and financial outcomes for these types of partnerships. Collecting this data during future projects will provide important evidence about the effectiveness of community-based collaborative interventions.

Limitations

The primary limitation to this study was that the majority of studies utilized for this review were descriptive studies for which a causal relationship was not identified. Process-based outcomes were reported much more frequently than clinical or financial outcomes. Some of the studies did not quantify their results, making it difficult to further assess their impact. Due to the limited number of studies included in this review, we are unable to assess the impact of individual programs to determine which were more efficient, and for which patient populations. Additionally, the specific role of each organization was not always fully described which limited the ability of the authors to draw conclusions about what types of organizations CPs should consider partnering with for specific types of services. While broad search terms were used to gather abstracts, it is possible that not all articles that discuss partnerships between CBOs and CPs were captured. Furthermore, professionals who work in non-academic organizations may not routinely publish their program findings. Lastly, our review assessed the role of primary and secondary preventative services, and therefore the impact of programs focusing on disease management were not assessed.

Conclusion

The limited literature describing partnerships between CPs and CBOs reinforces the need for well-designed studies that can help to determine the impact of these partnerships on access to preventive services and patient outcomes in the community setting.

Acknowledgements

Emily Ginier, Informationist at Taubman Health Sciences Library at the University of Michigan

Funding/support

None

Conflicts of interest

None

References

- 1.Coordinating care in the medical neighborhood: Critical components and available mechanisms . A multidisciplinary intervention for reducing readmissions among older adults in a patient-centered medical. In: Stranges PM, Marshall VD, Walker PC, Hall KE, Griffith DK, Remington T, editors. Am J Manag Care. 2. Vol. 21. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011. 2015. Feb, pp. 106–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Framework for action on interprofessional education & collaborative practice. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: 2016 update. Washington, DC: Interprofessional Education Collaborative; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4.The patient centered medical home: history, seven core features, evidence and transformational change. Robert Graham Center; 2007. Nov, pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barr M, Ginsburg J. American College of Physicians. The advanced medical home: a patient-centered physician-guided model of health care, position paper. Jan, 2006. pp. i–18.

- 6.Patient centered primary care collaborative History: major milestones for primary care and the medical home. [Accessed Nov 9;2017 ]. https://www.pcpcc.org/content/history-0

- 7.Martin JC, Avant RF, Bowman MA, et al. The Future of Family Medicine: a collaborative project of the family medicine community. Ann Fam Med. Mar 2, Apr 2, 2004. pp. S3–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Public law 111-148 – Patient protection and affordable care act. US government publishing office; Mar 23, 2010. [Accessed Nov 9;2017 ]. https://www.congress.gov/111/plaws/publ148/PLAW-111publ148.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marcus MT, Walker T, Swint JM, et al. Community-based participatory research to prevent substance abuse and HIV/AIDS in African-American adolescents. J Interprof Care. 2004 Nov;18(4):347–59. doi: 10.1080/13561820400011776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boltri JM, Davis-Smith YM, Zayas LE, et al. Developing a church-based diabetes prevention program with African Americans: focus group findings. Diabetes Educ. 2006 Nov;Dec;32(6):901–9. doi: 10.1177/0145721706295010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bond KT, Jones K, Ompad DC, Vlahov D. Resources and interest among faith based organizations for influenza vaccination programs. J Immigr Minor Health. 2013 Aug;15(4):758–63. doi: 10.1007/s10903-012-9645-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abara W, Coleman JD, Fairchild A, et al. A faith-based community partnership to address HIV/AIDS in the southern United States: implementation, challenges, and lessons learned. J Relig Health. 2015 Feb;54(1):122–33. doi: 10.1007/s10943-013-9789-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong EC, Chung B, Stover G, et al. Addressing unmet mental health and substance abuse needs: a partnered planning effort between grassroots community agencies, faith-based organizations, service providers, and academic institutions. Ethn Dis. 2011 Summer;21(3) Suppl 1:S1, 107–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stewart JM. A multi-level approach for promoting HIV testing within African American church settings. 2015 Feb;29(2):69–76. doi: 10.1089/apc.2014.0160. AIDS Patient Care STDS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chung B, Wong E, Litt P, et al. Project overview of the Restoration Center Los Angeles: steps to wholeness--mind, body, and spirit. Ethn Dis. 2011 Summer;21(3) Suppl 1:S1, 100–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mann BD, Sherman L, Clayton C, et al. Screening to the converted: an educational intervention in African American churches. J Cancer Educ. 2000 Spring;15(1):46–50. doi: 10.1080/08858190009528653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maurana CA, Clark MA. The health action fund: a community-based approach to enhancing health. Journal of Health Communication. 2000;5:243–54. doi: 10.1080/10810730050131415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allen ML, Hurtado GA, Yon KJ, et al. Feasibility of a parenting program to prevent substance use among Latino youth: a community-based participatory research study. Am J Health Promot. 2013 Mar;Apr;27(4):240–4. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.110204-ARB-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Community based organization: community service Convoy of Hope. [Accessed Nov 9;2017 ]. https://www.convoyofhope.org/about/

- 20.Kelling SE. Exploring the accessibility of community pharmacy services. Inov Pharm. 2015;6(3) Article 210. [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Network of Libraries of Medicine Book 1 – Getting started with community-based outreach. [Accessed Nov 9;2017 ]. https://nnlm.gov/neo/guides/bookletOne508

- 22.Rosenfeld LA, Etkind P, Grasso A, et al. Extending the reach: local health department collaboration with community pharmacies in Palm Beach County, Florida for H1N1 influenza pandemic response. J Public Health Management Practice, Sept. 2011;17(5):439–48. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e31821138ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marlin RW, Young SD, Bristow CC, et al. Piloting an HIV self-test kit voucher program to raise serostatus awareness of high-risk African Americans, Los Angeles. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1226):1–5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meyerson BE, Carter G, Lawrence C, et al. Expanding HIV testing in African American communities through community-based distribution of home-test vouchers. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2016;30(3):141–145. doi: 10.1089/apc.2015.0243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cadilhac DA, Kilkenny MF, Johnson R, et al. The know your numbers (KYN) program 2008 to 2010: impact on knowledge and health promotion behavior among participants. International Journal of Stroke. Jan. 2015;10(1):110–6. doi: 10.1111/ijs.12018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weidle PJ, Lecher S, Botts LW, et al. HIV testing in community pharmacies and retail clinics: A model to expand access to screening for HIV infection. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2014;54(5):486–492. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2014.14045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harris AC, Doucette WR, Reist JC, Nelson KE. Organization and results of student pharmacist bone mineral density screenings in women. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2011;51(1):100–104. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2011.09062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Segura A, Miller FA, Foz G, Oriol y Bosch A. Towards unity for health in the Barceloneta: An innovative experience in community-based primary health care. Educ Health (Abingdon) 2007;20(2):42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]