Abstract

PURPOSE

To determine informative clinical and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) characteristics of patients with symptomatic adult acquired, comitant esotropia due to decompensated esophoria.

DESIGN

Retrospective, interventional case series.

METHODS

Setting:

Institutional.

Study Population:

Patients with decompensated esophoria who developed acute acquired comitant esotropia.

Observation Procedures:

Ophthalmic examination, stereopsis, and strabismus measurements at distance and near using prism cover tests in diagnostic gaze positions were performed. Patients underwent high resolution surface coil MRI of extraocular muscles with target fixation, and MRI of the brain. Strabismus surgery was performed under topical anesthesia with adjustable sutures wherever possible. Paired t-test was used to evaluate post-operative changes with 0.05 considered significant.

Main Outcome Measure:

Clinical and MRI characteristics and surgical outcome of patients with decompensated esophoria.

RESULTS

Eight cases were identified of mean age 29 ± 9.4 (range: 20–48) years having gradually progressive intermittent horizontal, binocular diplopia for 10 months to 3 years. Mean pre-operative esotropia was 31±12 at distance and 29±12 at near, although this was intermittent in five patients who exhibited enhanced fusional divergence. Neurological evaluation and MRI of brain, orbits, and extraocular muscles were unremarkable in all cases. Orthotropia was successfully restored in all by standard or enhanced doses of bimedial rectus muscle recession surgery, improving mean stereoacuity from 535 to 68 arc seconds, although five patients exhibited 2–14 asymptomatic residual esophoria.

CONCLUSION

Decompensated esophoria is a benign clinical entity causing acute, acquired, comitant esotropia treatable with enhanced medial rectus recession.

Keywords: esophoria, esotropia

INTRODUCTION

Acute, acquired, comitant esotropia (AACE) presents in early adulthood with sudden onset of large angle esotropia, usually preceded by intermittent diplopia, in a previously orthotropic individual1. Earlier reports have classified AACE on the basis of clinical features and different types of underlying refractive errors2,3. Some cases have been reported in association with various underlying neurological disorders such as brain tumors4, Arnold Chiari malformation5–8, idiopathic intracranial hypertension 9, and cerebellar ataxia10. Possible structural brain disease is the rationale for detailed neurological examination in AACE, yet the necessity of expensive and time-consuming radiological investigations has remained controversial.

Any latent binocular misalignment that becomes symptomatic is considered to be a phoria that has “decompensated.” Symptoms of decompensated esophoria may range from simple headache to severe asthenopia and diplopia. Since phorias are generally considered benign, decompensated esophoria has not been emphasized in the literature as an important cause of AACE, in contrast to the identification of cases associated with more classical pathologies that may have thus received disproportionate emphasis. Underlying mechanisms for the decompensation of phorias are poorly understood, although authors have suggested a few. A large angle pre-existing esophoria in setting of close working distance has been described as one cause of decompensation to acute esotropia11, although this explanation begs the question of the origin of the initial esophoria. Godts et al. have reported that esophoric patients initially compensate using divergence fusional reserves12. It has been proposed that stress, physical illness, or aging can diminish those reserves to the point of insufficiency to compensate for the phoria, thereby unmasking large angle AACE12. Diseases that disrupt sensory fusion pathways may plausibly decompensate an existing esophoria. Such sensory conditions include uncorrected large refractive errors, cataract, and optic neuropathies11.

The dilemma for the modern clinician is that acute onset of large angle esotropia (ET) in a young adult might occasionally have ominous neurological consequences, or alternatively represent only decompensation of an entirely benign and longstanding phoria. Additional characterization to secure diagnosis of the latter presentation would be clinically useful. We conducted this study with the objectives to determine the clinical and magnetic resonance imagining (MRI) characteristics, as well as treatment outcome, of the patients with decompensated esophoria who presented with large angle AACE.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

After approval of a protocol approved by the institutional review board for Protection of Human Subjects, at University of California, Los Angeles, we reviewed the clinical and surgical records of patients with AACE who presented at our institute from 2015 to 2017. All patients underwent detailed history and ophthalmic examination that included assessment of unaided and best corrected visual acuity, refraction, ductions and versions in secondary and tertiary gazes, Titmus fly stereopsis, and strabismus deviation measured at distance and near using alternate and prism cover tests in diagnostic gaze positions. Preoperative convergence fusional amplitudes were measured with base-out prisms in two cases. All patients underwent high resolution surface coil MRI of the extraocular muscles with target fixation13, and brain MRI with and without intravenous contrast to rule out structural lesions.

Surgical patients were offered the option of adjustable sutures. Strabismus surgery under topical anesthesia was performed using 1% lidocaine hydrochloride with monitored anesthesia care provided by anesthesiologists. Small doses of intravenous propofol were given if the patient felt discomfort during surgery14. Postoperative adjustments were performed with the patient seated, with appropriate refractive glasses, and targets located centrally both at near and far. For patients undergoing bilateral surgery with adjustable sutures, the adjustment was performed in one of the two operated eyes. The amount of surgery performed was recorded and its effect on ocular alignment was measured at follow-up visits.

Statistical analysis was performed using the program SPSS 20.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The paired t-test was applied to evaluate change in pre-and postoperative deviations and stereopsis with 0.05 considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Eight cases of AACE were identified having mean age 29 ± 9.4 (range: 20–48) years presenting with gradually progressive intermittent, horizontal, binocular diplopia of 10 months to 3 years duration (Table 1, 2). There were equal numbers of males and females. No patient had previously undergone occlusion therapy, trauma, or significant psychological stress. The mean spherical equivalent refraction was −2.2 ± 3.3D and −2.5 ± 3.5D in the right and left eyes, respectively. Best corrected visual acuity was 20/20 in both eyes of all patients. Ocular versions were full in all patients, with normal saccades and no nystagmus in any gaze position. Mean pre-operative esotropia in central gaze was 31±12Δ for distance and 29±12Δ for near, although this was intermittent in five patients who exhibited enhanced fusional divergence. Mean pre-operative esotropia in right, left, up and down gazes was 30±10Δ, 30±10Δ, 29±11Δ, and 30±9Δ respectively. Mean preoperative stereoacuity was 535±1007 (range: 40 – 3000) arc seconds. Convergence fusional amplitudes during remote viewing were 30 and 16Δ two patients, respectively.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of Patients with Decompensated Esophoria

| No. | Age/Sex (years) | Symptom Duration (Months) | Spherical Equivalent Refraction (D) | Preoperative Esodeviation (Δ) | Preoperative Stereo (Arc sec) | Postoperative Stereo (Arc sec) | Medial Rectus Recession Both Eyes (mm) | Follow-Up (Months) | Postoperative Esodeviation (Δ) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OD | OS | Far | Near | Far | Near | |||||||

| 1 | 48/F | 10 | −8.50 | −9.50 | 50 | 50 | 140 | 60 | 6 | 10 | Ortho | Ortho |

| 2 | 37/M | 12 | +0.25 | −0.25 | 18 | 30 | 200 | 60 | 3.5 | 1 | 10 | 14 |

| 3 | 20/M | 12 | −2.75 | −2.25 | 30 | 30 | 40 | 40 | 4.5 | 6 | Ortho | 8 |

| 4 | 24/F | 36 | −0.25 | −0.75 | 35 | 25 | 400 | 40 | 5 | 7 | Ortho | Ortho |

| 5 | 25/M | 12 | 0.00 | −0.50 | 12 | 10 | 40 | 40 | 3.5 | 2 | 4 | Ortho |

| 6 | 24/F | 36 | −6.00 | −6.00 | 35 | 30 | 3000 | 40 | 6 | 2 | Ortho | Ortho |

| 7 | 22/F | 36 | −1.00 | −1.50 | 40 | 40 | 400 | 200 | 5.5 | 6 | Ortho | 8 |

| 8 | 31/M | 30 | +0.50 | +0.5 | 25 | 20 | 60 | 60 | 5 | 2 | 4 | Ortho |

F – female. M – male.

Table 2.

Clinical Profile of Study Population

| Variable | Mean | Standard Deviation | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) | 28.9 | 9.4 | 20 – 48 |

| Duration of Intermittent Diplopia (Months) | 23.0 | 12.5 | 10 – 36 |

| Spherical Equivalent Right Eye | −2.22 | 3.34 | −8.50 to +0.50 |

| Spherical Equivalent Left Eye | −2.53 | 3.45 | −9.50 to +0.50 |

| Divergence Fusional Amplitude (Δ) | 24 | 11.3 | 16 – 32 |

| Total Medial Rectus Recession Dose (mm) | 9.6 | 2.0 | 7 – 12 |

| Follow up Duration (Months) | 4.5 | 3.2 | 1 – 10 |

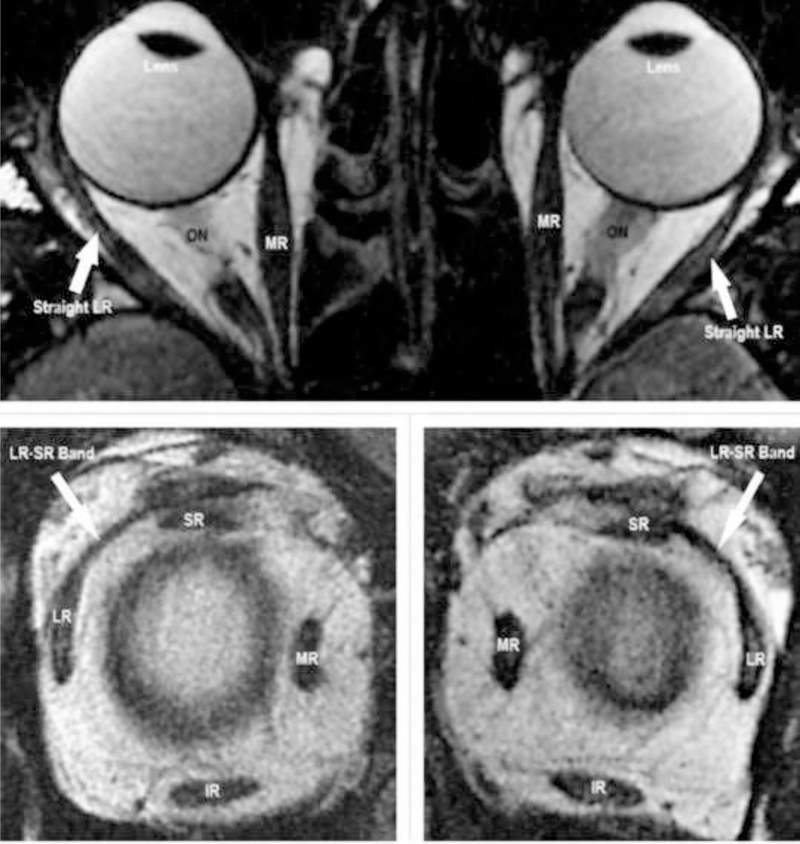

Anterior and posterior segment ocular examinations were normal in all patients. All patients underwent neurological evaluation using brain MRI. No patient demonstrated a brain or orbital tumor, Arnold Chiari malformation, idiopathic intracranial hypertension, cerebellar disease or radiological evidence of any other neurological disease. High resolution surface coil MRI of extraocular muscles with target fixation revealed absence of signs of sagging eye syndrome, lateral rectus atrophy, and pulley displacement, staphylomata, heavy eye syndrome, or elongation of muscle paths (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1:

MRI demonstrating intact LR-SR band ligament bilaterally in a case of AACE. IR – inferior rectus muscle. LR – lateral rectus muscle. MR – medial rectus muscle. ON – optic nerve. SR – superior rectus muscle.

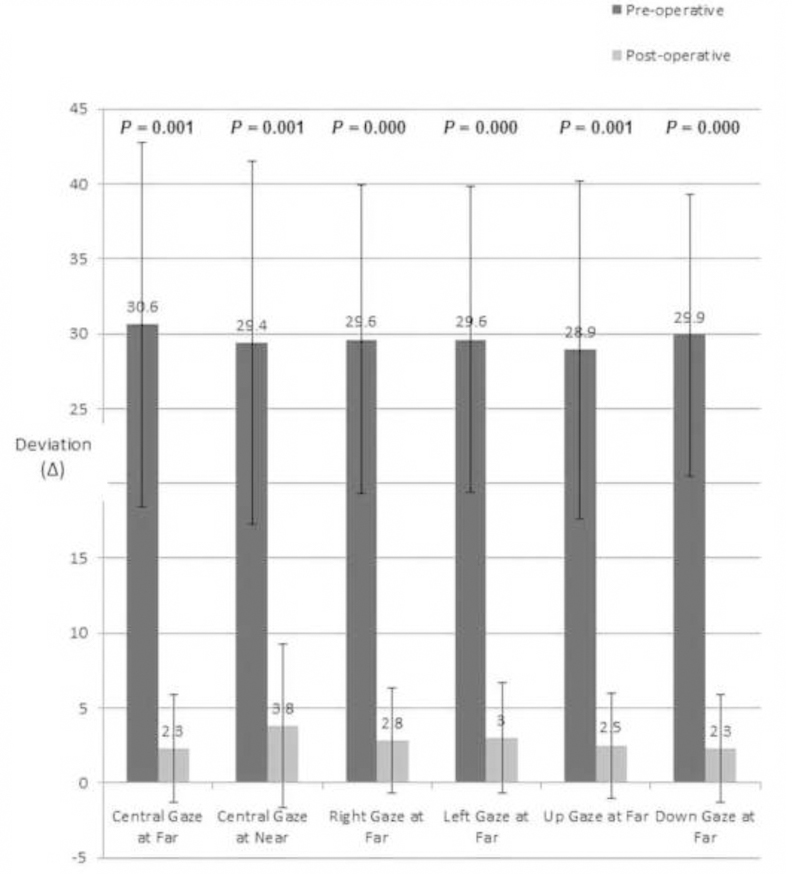

All patients underwent bimedial rectus recession with adjustable sutures except for one patient considered a poor candidate for suture adjustment who underwent surgery with fixed sutures. Using surgical dosage recommended by Park et al15, we performed mean bilateral medial rectus recession of 4.8±1.0 (range: 3.5 – 6.0) mm. Single binocular vision was surgically restored in all, although five patients exhibited 2–14 Δ asymptomatic residual esophoria. Mean stereoacuity improved from 535 to 68 arc seconds. Mean postoperative esophoria at the latest follow-up visit at 4.5±3.2 (range: 1–10) months was 2.3±3.6Δ at far and 3.7±5.5Δ at near (p = 0.001 and 0.001, respectively, Fig. 2).

Fig. 2:

Pre- And Post-Operative Esodeviation.

DISCUSSION

We present here a series of young adults with gradually progressive intermittent, horizontal, binocular diplopia that suddenly converted to constant, comitant, large angle esotropia. Since these patients did not fit traditional subtypes of AACE, we considered the benign possibility of simple esophoria that decompensated over time to acute, symptomatic diplopia due to esotropia. Patients with decompensating esophoria slowly deteriorate and present with esotropia only when their enhanced divergence fusional amplitudes no longer suffice. This makes decompensated esophoria progressing to esotropia a distinct and generally benign diagnosis. Mild surgical undercorrections are common yet asymptomatic due to enhanced divergence fusional amplitudes.

The historical classification of AACE has been into three types depending, on clinical features and etiology presumed of the basis of relatively weak or absent evidence. Type I occurs following monocular occlusion or vision loss secondary to ocular disease or trauma16, and is not inconsistent with decompensation of an esophoria due to sensory deprivation. Type II is characterized by presence of hypermetropia and reportedly occurs after psychological stress or shock17; such a postulated etiology is subject to recall bias and has not been supported by a controlled study. Type III reportedly occurs in patients with uncorrected myopia of −5.00 D or more17,18, although given the extremely high prevalence of myopia in the 21st century19,20 this would seem a highly non-specific association indeed. One hypothesized mechanism for this type of esotropia is putative increased medical rectus muscle tone due to excessive convergence during near viewing by uncorrected myopes17; this theory is undercut both by the absence of any measurable index of medial rectus tonus, and the relative rarity of AACE relative to the very high prevalence of myopia today. Some patients with AACE have large esotropia at distance but close to orthophoria at near17. Some authors have excluded such patients from the aforementioned classification of AACE, instead labeling them as having divergence insufficiency or divergence paralysis esotropia21,22. Chaudhuri et al. reported that inferior sagging of lateral rectus muscle pulley and progressive degeneration of its suspensory ligament were major causes of divergence paralysis esotropia having a mechanical rather than a neurological basis23.

The patients in the present case series fit none of the aforementioned historical types of acute onset esotropia. None had history of any ocular injury, monocular vision loss, or occlusion. Similarly, none had significant hypermetropia or admitted to recent emotional trauma or psychological stress. Lastly, while two of our patients had myopia exceeding −5.00 D, all had habitually worn appropriate refractive correction for many years. This feature distinguishes the two high myopes here from traditional type III that hypothesized excessive strengthening of medial rectus muscles. as a cause of esotropia in uncorrected high myopia. Presence of similar comitant esotropia for both near and far viewing excludes divergence paralysis esotropia in our patients23, and they are younger than typical for sagging eye syndrome. Normal saccades and comitant pre-operative deviations for far (30.6 ± 12.2 Δ), near (29.4 ± 12.1 Δ), right (29.6 ± 10.3 Δ) and left (29.6 ± 10.0 Δ) lateral gazes are inconsistent with muscle paresis due to cranial neuropathy. Since the neurological and radiological investigations were unrevealing, and no neurological disorders emerged on follow-up, it is highly unlikely that brain lesions caused the AACE in the current series. Young patient age, normal adnexal examination findings, absence of hypotropia, absent deep superior orbital sulci, and unremarkable MRI of the extraocular muscles and orbital tissues exclude the possibility of heavy eye and sagging eye syndromes in our patients24,25.

Godts et al. presented a series of elderly patients with acute esotropia in whom there were changes in esophoria and accompanying divergence fusional amplitudes over a 12 year period. Elderly patients exhibited increase in distance esodeviation from 3 to 8Δ with a simultaneous decrease of 3 – 6Δ in divergence fusional amplitudes over a 12 year span. Patients with small esodeviations were successfully managed using prisms; however, surgical management was proposed for large angle deviations12.

Lyons et al. presented a series of 10 patients with AACE, and reported that decompensation of a pre-existing phoria or monofixation syndrome were the commonest etiologies 26. Spierer et al. presented a series of 10 adult patients who had significant myopia and developed sudden large angle esotropia17. They restored binocularity surgically in most patients. Spierer et al proposed that these patients had “acute concomitant esotropia of adulthood.” We believe that this report probably encompasses patients with decompensated esophoria due to decline in fusional amplitudes.

Another notable aspect in the current series is the diminutive response to conventionally dosed strabismus surgery in AACE. We performed bilateral medical rectus recession following the surgical dosage recommended by Park et al.15 But despite seemingly appropriate surgical dosing, five (71%) patients had residual esophoria of 2–14Δ. This suggests that surgical dosing in AACE should be augmented to avoid undercorrections, and argues for the advantage of adjustable sutures. Chaudhuri et al. reported that dosing must be increased in patients with divergence paralysis esotropia due to sagging eye syndrome because of elongation of rectus muscles, and inferolateral displacement of the lateral rectus pulleys23,25. Though our patients did not have extraocular muscle abnormalities or signs of sagging eye syndrome on high resolution surface coil MRI scans, the residual esophoria in most of them argues that the surgical target angle be augmented by an additional 10Δ in AACE.

Mikhail et al reported the adjustable suture strabismus surgical outcome of patients with AACE27. In adults, the average preoperative ET was 22 (range 6– 40) Δ at distance and 20 (range 4–42) Δ at near. At 2 weeks follow-up, ET was 3 (range 0–18) Δ at distance and 4 (range 0– 20) Δ at near. At 4–6 months follow-up, mean was 3 (range: ET 20 – XT 20) Δ at distance and 4 (range: ET 14–XT 14) Δ at near. Their success rate, liberally defined as within 12 Δ of orthotropia both at far and near at 2 weeks and 6 months postoperatively, was 97% and 80%, respectively. As long as the patients could fuse in primary position and overcome diplopia, the investigators advocated conservative surgeries in such cases to prevent overcorrections27. However, esophoria of 12Δ or more is likely to present with symptomatic diplopia at distance, especially in lateral gazes25.

We propose that patients with AACE who have no other neurological signs or symptoms probably have decompensated esophoria that becomes symptomatic for diplopia when their enhanced divergence fusional amplitudes no longer safely exceed the esophoria. This makes decompensated esophoria progressing to ET a generally benign diagnosis. Strabismologists should consider the possibility of decompensated esophoria attempting to classify the AACE into one of the presumptive historical types that lack etiological plausibility in the modern era.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS/DISCLOSURE

a) Funding Support: Supported by U.S. Public Health Service, National Eye Institute: grants EY008313 and EY000331. J. Demer is Arthur L. Rosenbaum Professor of Ophthalmology.

b) Financial Disclosures:

Muhammad Hassaan Ali: No financial disclosures

Shauna Berry: No financial disclosures

Azam Ali Qureshi: No financial disclosures

Narissa Rattanalert: No financial disclosures

Jospeh L. Demer: National Eye Institute Grant EY008313 and Research to Prevent Blindness.

Biography

Muhammad Hassaan Ali, M.D

Muhammad Hassaan Ali, M.D. is fellow in pediatric ophthalmology and adult strabismus at Stein Eye Institute, University of California, Los Angeles. He completed basic medical education and ophthalmology residency at Allama Iqbal Medical College, Jinnah Hospital, Lahore, Pakistan with honors. He will start further fellowship in pediatric ophthalmology at Sickkids Hospital, Toronto in 2019. Research interests include management of complex strabismus and application of novel imagining techniques in various ocular motility and anterior segment disorders.

Biosketch Photo: Ali

Joseph L. Demer, M.D., Ph.D.

Arthur L. Rosenbaum Professor of Pediatric Ophthalmology

Joseph L. Demer, M.D., Ph.D. is Arthur Rosenbaum Professor, Chief of Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, and Professor of Neurology, at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. He directs the Ocular Motility Clinical Laboratory, and the EyeSTAR Program. Dr. Demer received the Friedenwald Award from ARVO, and a Recognition Award from Alcon Research Institute, for his work on biomechanics of extraocular muscles and orbital connective tissues. Dr. Demer is a gold fellow of ARVO.

Biosketch Photo: Demer

Footnotes

Proprietary Interest: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Clark AC, Nelson LB, Simon JW, Wagner R, Rubin SE. Acute acquired comitant esotropia. Br J Ophthalmol 1989;73(8):636–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simon AL, Borchert M. Etiology and prognosis of acute, late-onset esotropia. Ophthalmology 1997;104(8):1348–1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mittelman D Age-related distance esotropia. JAAPOS 2006;10(3):212–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee J-M, Kim S-H, Lee J-I, Ryou J-Y, Kim S-Y. Acute comitant esotropia in a child with a cerebellar tumor. Korean J Ophthalmol 2009;23(3):228–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Defoort-Dhellemmes S, Denion E, Arndt CF, Bouvet-Drumare I, Hache J-C, Dhellemmes P. Resolution of acute acquired comitant esotropia after suboccipital decompression for Chiari I malformation. Am J Ophthalmol 2002;133(5):723–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hentschel SJ, Yen KG, Lang FF, Chiari I. malformation and acute acquired comitant esotropia: case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg Pediatr 2005;102(4):407–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weeks CL, Hamed LM, Chiari I. Treatment of acute comitant esotropia in malformation. Ophthalmology 1999;106(12):2368–2371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biousse V, Newman NJ, Petermann SH, Lambert SR, Chiari I. Isolated comitant esotropia and malformation. Am J Ophthalmol 2000;130(2):216–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoyt CS, Fredrick DR, Rosenbaum A, Santiago A,WB, Serious Neurologic Disease Presenting as Comitant Esotropia Vol 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dikici K, Cicik E, Akman C, Tolun H. Kendiroŭlu G, Cerebellar astrocytoma presenting with acute esotropia in a 5 year-old girl. Int Ophthalmol 1999;23(3):167–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evans BJ. Optometric prescribing for decompensated heterophoria. Optom Pract 63 2008;9(2). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Godts D, Mathysen DG. Distance esotropia in the elderly. Br J Ophthalmol 2013;97(11):1415–1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Demer JL, Ortube MC, Engle EC, Thacker N. High-resolution magnetic resonance imaging demonstrates abnormalities of motor nerves and extraocular muscles in patients with neuropathic strabismus. JAAPOS 2006;10(2):135–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fang ZT, Keyes MA. A novel mixture of propofol, alfentanil, and lidocaine for regional block with monitored anesthesia care in ophthalmic surgery. J Clin Anesth 2006;18(2):114–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parks M, Mitchell P, Wheeler M. Concomitant Esodeviations. In: Tasman W, Jaeger E, eds. Duane’s Foundations of Clinical Ophthalmology Vol 1 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Pihiladelphia, PA; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoyt CS, Good WV. Acute onset concomitant esotropia: when is it a sign of serious neurological disease? Br J Ophthalmol 1995;79(5):498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spierer A Acute concomitant esotropia of adulthood. Ophthalmology 2003;110(5):1053–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chisholm SA, Archer S, Gappy C. Acute acquired comitant esotropia in older children and adults. JAAPOS. e28 2016;20(4). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holden BA, Fricke TR, Wilson DA, et al. Global prevalence of myopia and high myopia and temporal trends from 2000 through 2050. Ophthalmology 2016;123(5):1036–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greene PR, Greene JM. Advanced myopia, prevalence and incidence analysis. Int Ophthalmol 2017:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Krohel GB, Tobin DR, Hartnett ME, Barrows NA. Divergence paralysis. Am J Ophthalmol 1982;94(4):506–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ridley-Lane M, Lane E, Yeager LB, Brooks SE. Adult-onset chronic divergence insufficiency esotropia: clinical features and response to surgery. JAAPOS 2016;20(2):117–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chaudhuri Z, Demer JL. Medial rectus recession is as effective as lateral rectus resection in divergence paralysis esotropia. Arch Ophthalmol 2012;130(10):1280–1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tan RJD, Demer JL. Heavy eye syndrome versus sagging eye syndrome in high myopia. JAAPOS 2015;19(6):500–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chaudhuri Z, Demer JL. Sagging eye syndrome: connective tissue involution as a cause of horizontal and vertical strabismus in older patients. JAMA Ophthalmol 2013;131(5):619–625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lyons CJ, Tiffin PA, Oystreck D. Acute acquired comitant esotropia: a prospective study. Eye 1999;13(5):617–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mikhail M, Flanders M. Clinical profiles and surgical outcomes of adult esotropia. Can J Ophthalmol J Can dOphtalmologie 2017;52(4):403–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.