Abstract

Organizations regularly make significant investments to ensure their teams will thrive, through interventions intended to support their effectiveness. Such team development interventions (TDIs) have demonstrated their value from both a practical and empirical view, through enabling teams to minimize errors and maximize expertise and thereby advance organizational gains. Yet, on closer examination, the current state of the TDI literature appears so piecemeal that the robustness of extant scientific evidence is often lost. Accordingly, we seek to provide a more cohesive and dynamic integration of the TDI literature, evolving thinking about TDIs toward a system of interventions that can be optimized. Drawing on the existing theoretical and empirical literatures, we first broadly define TDIs. We then offer an in-depth look at the most common types of TDIs, in terms of summarizing the state of the science surrounding each TDI. Based on this review, we distinguish features that make for an effective TDI. We then advance a more integrative framework that seeks to highlight certain interventions that are best served for addressing certain issues within a team. In conclusion, we promote a call for evolving this robust yet disjointed TDI literature into a more holistic, dynamic, and intentional action science with clear empirical as well as practical guidance and direction.

INTRODUCTION

Time and money have always been critical com- modities for organizations; indeed, one of the major goals of an effective organization is to maximize resources while minimizing costs. The incorporation of teams has increasingly become a prominent solution used by organizations to achieve this balance. Teams are defined as two or more individuals inter- acting dynamically, interdependently, and adaptively toward a common goal, with each member having a specific role to fill within the boundary of the team (Salas, Dickinson, Converse, & Tannenbaum, 1992). In part, the prevalence of teams within orga- nizations is due to the complex problems that orga- nizations often face and the synergistic benefits that the use of teams can provide to organizations—that is, teams offer the capability to achieve what cannot be accomplished by one individual acting alone (Hackman, 2011).

Some have heralded teams to be a basic building block of organizations today (Stewart & Barrick, 2000). Subsequently, there is no lack of theory, research, and consultants in the area of teams and their development (Cannon-Bowers & Bowers, 2010). In fact, given their prominence in organizations, significant investments have been devoted to ensuring teams will succeed, including investment in scholarship as well as practical tools and resources (Lacerenza, Marlow, Tannenbaum, & Salas, 2018; Shuffler, DiazGranados, & Salas, 2011). As a result, numerous scientific reviews have been undertaken to extract the individual, team, system, organizational, and environmental factors that define and shape effective teamwork (Humphrey & Aime, 2014; Mathieu, Maynard, Rapp, & Gilson, 2008; Salas, Shuffler, Thayer, Bedwell, & Lazzara, 2015).

Yet, even with this aforementioned knowledge at hand, organizational teams still fail on a regular— sometimes daily—basis (Tannenbaum, Mathieu, Salas, & Cohen, 2012). Furthermore, although some organizational teams may not actually be failing, their performance may be less than desirable, plateauing or starting to spiral toward decline. Perhaps, even more challenging, the factors that help a team maintain adequate performance may be different from those that assist a team surpass their current performance levels and attain superior performance. As a result, teams, leaders, and organizations often need to intervene by leveraging a range of mechanisms, conditions, tools, and resources that can help them take action to enhance team effectiveness (Hackman, 2011; Kozlowski & Ilgen, 2006).

We broadly define these actions taken to alter the performance trajectories of organizational teams as TDIs. Given the complex nature of team effectiveness, it is not surprising that there is a wide array of these TDIs discussed within the scholarly organizational literature. When designed and implemented using evidence-based practices and principles from the scientific literature, TDIs can serve a vital role in improving team effectiveness (Shuffler et al., 2011). However, the often lucrative nature of team development consulting has also resulted in many popular culture resources that are not actually effective. As a result, scientifically derived, evidence-based TDIs are too often lumped with more haphazard, “feel good” TDIs, as ifthey are all one in the same. Certainly, team building (TB) comes to mind as an often misused and abused TDI catchall that can evoke strong, overly positive or negative affective reactions based on experiences (Cannon-Bowers & Bowers, 2010). Further complicating the issue, although there are distinct types of TDIs recognized in the literature that may potentially complement one another, they have been developed and evaluated in relative isolation from one another (Weaver, Dy, & Rosen, 2014) and to varying degrees of scientific rigor. Accordingly, an organized perspective that distinguishes TDIs backed by a solid science is much overdue.

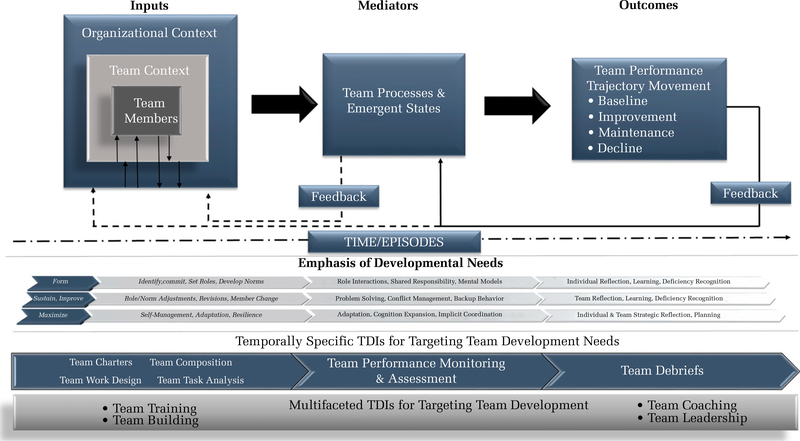

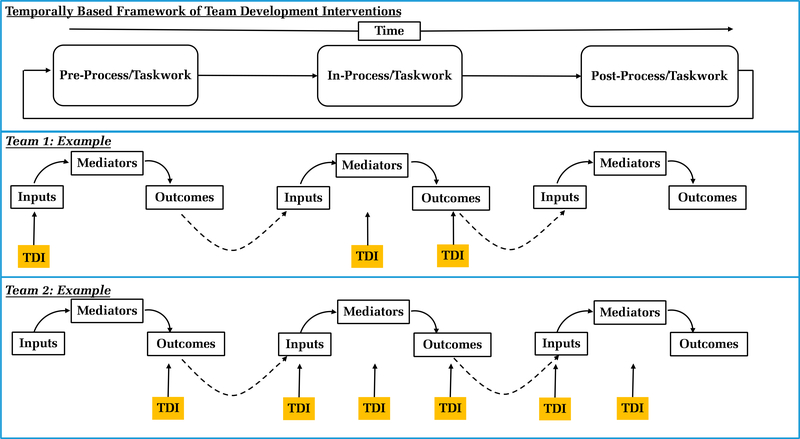

As such, this review addresses four major needs that must be resolved to advance TDI research and practice in organizations. First, we address the need for a clear defmition of what a TDI is—moving beyond what may broadly be considered a TDI to more specifically distinguishing the features of an effective TDI (Need 1). Second, we offer in one place a more indepth review of the different types of TDIs that have garnered substantial attention in the academic litera- ture (Need 2). In identifying major themes in these literatures, we offer guidance as to the state of the science in terms of each TDI’s current or potential contribution. Third, in an effort to discuss what makes TDIs effective, we leverage a relatively simple heuristic of “what,” “why,” “who,” “when,” and “how,” to synthesize the impact that TDI characteristics have in shaping whether a particular TDI is ultimately successful or not for a given context or team. Using our definition and this heuristic, we address a third need in terms of creating a foundation for better understanding how the various TDIs can be better integrated so they may work together (Need 3). We leverage structural elements of prominent team effectiveness models (i.e., McGrath, 1964; Marks, Mathieu, & Zaccaro, 2001), and based on our review of the literature, introduce an integrative framework that considers dynamic team developmental needs to offer direction for determining what TDI or combination of TDIs may be most effective in shaping team performance trajectories.

Last, to push the science and practice of TDIs toward a more holistic evolution (Need 4), we conclude with future directions in terms of considerations regarding potential advancements for empirically and methodologically applying a more integrative perspective to TDIs, especially across organizational contexts. Each of these needs is particularly important to address, given that we view TDI research and practice as being at a critical crossroads: TDIs can either evolve dynamically to keep up with practical organization demands or continue with the same static lens that is quickly becoming irrelevant.

CONCEPTUALIZING TDIs: AN ORGANIZING DEFINITION

We began our introduction with the most inclusive definitions in terms of what could possibly be included as a TDI. This is purposeful in terms of directing a focus on bounding TDIs as requiring intentional action(s) targeted at team performance trajectories. More specifically, these actions may attempt to (1) improve and support teams that may be struggling or failing, (2) maintain and sustain teams that are adequately performing, and (3) grow and maximize the capacities of teams ready to mature to a higher level of performance. As such, this drills down from broader categories such as organizational development interventions or human resource efforts, to set the team as the focal unit of analysis for this type of intervention. However, the simplistic nature of this definition leaves room for including TDIs that may make attempts yet fail every time to impact team performance trajectories. Moving from this rather broad conceptualization, our first aim is to drill down further into TDIs as a meaningful term, reviewing the extant scientific literature to critically evaluate what an effective TDI looks like and what the broad state of the science looks like regarding trends and patterns in TDI research.

IDENTIFYING IMPACT: CURRENT STATE OF THE SCIENCE WITHIN TDIs

Literature Review Approach

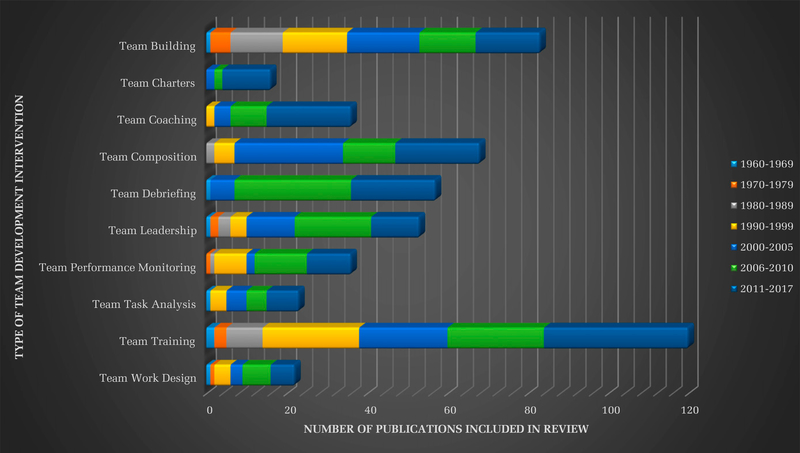

We conducted a series of searches for academic publications within the broader organizational behavior, management, and psychology literatures. Databases searched included PsycInfo, Academic OneSource, MedLine, and Google Scholar. Broad and more specific terms, such as “TDIs,” “team development,” “team training (TT),” and “TB,” were used; a full list is available from the first author. When systematic reviews and meta-analyses of TDIs were identified, the reference lists were searched to ensure all relevant articles were included. Although we did not set a timeframe for our searches, the vast majority of sources came from the past 50 years, in line with similar reviews that acknowledge the early 1970s as the start of a concerted interest in team development (Tannenbaum, Beard, & Salas, 1992). Likewise, we excluded sports team sources, a common occurrence in the team literature due to the niche nature of such work as compared with other organizational teams (Klein, DiazGranados, Salas, Le, Burke, Lyons, & Goodwin, 2009; Salas, Cooke, & Rosen, 2008a). Finally, to be retained, the article had to describe some clear form of TDI.

Our initial searches in these sources resulted in more than 5,000 potentially relevant articles that were then sorted to remove irrelevant articles (e.g., sports coaching and patient health interventions performed by health-care teams instead of team interventions). In particular, although some of our resulting TDI types [e.g., team leadership (TL), team composition (TCo), and team performance monitoring] have broader literatures beyond just that focused on an intervention perspective, we excluded any sources that did not focus on interventions in some form. Both qualitative and quantitative empirical articles were retained if the intervention they described met the aforementioned broad definition, including case studies, experimental, and quasi- experimental designs. In addition, we retained sys- tematic reviews and meta-analyses for confirming our overarching themes within and across TDIs. Overall, our final sample consisted of 514 articles.

Next, we reviewed these articles with two intentions. First, we examined the approaches, findings, and contributions to establish common themes across TDIs, to address Need 3 (integration of TDIs) and Need 4 (future directions). Second, we grouped articles based on the types of TDIs they addressed, enabling us to develop within-TDI themes regarding quality of the research thus far, as well as important themes for understanding the impact of and considerations for different TDIs to address Need 1 (defining TDIs) and Need 2 (review of the literature). Each of the first three authors reviewed the literatures separately and then met to discuss themes within and across TDIs, reconciling any disagreements with one another and with input from the fourth author to produce a final set of themes within and across TDIs.

Current State of the Science

There is a value in addressing an in-depth review (Need 2), especially in terms of identifying the TDIs that target the developmental needs of teams. Specifically, there have been several dominant view- points of how teams develop: (1) teams develop linearly (i.e., consistently in the same pattern over time; Tuckman, 1965) or (2) teams experience some type of temporally based punctuated shift as described in the punctuated equilibrium model (Gersick, 1988). Recognizing that teams may function more cyclically than linearly, other models have further incorporated this structure, such as in the input-process-output (IPO) model advanced by McGrath (1984), Steiner (1972), and Hackman (1987), that conceptualizes team effectiveness as a system of inputs, processes, and outcomes that influence one another. By using the lens of the IPO model, we are able to organize our review based on the target of each TDI reviewed. Similar reviews exploring the effectiveness of individual TDIs do exist in the extant literature and we have relied on these to guide us, especially in identifying and synthesizing key empirical findings. However, each review highlights only a single TDI at a time, limiting our ability to create a more comprehensive perspective. Thus, although a full empirical, meta-analytical review is beyond the scope of our current review, it is critical to provide some deeper insight into the different categories of TDIs.

As such, the following section offers summaries of ten types of TDIs, organized by the IPO framework. In particular, TDIs that primarily focus on team inputs include team task analysis (TTA), TCo interventions, team work designs (TWDs), and team charters (TChs). Team process-focused TDIs include team performance monitoring and assessment (TPMA), whereas the intervention focused on team outcomes is team debriefs (TD). Finally, there are several TDIs we label as “multifaceted,” given that they can address factors from more than one IPO category. These multifaceted TDIs include TB, TT, team coaching (TCa), and TL. Because of the variance in the depth of literature for each category, some offer more empirical evidence than others.

Team Task Analysis (TTA)

Definition and evidence assessment.

Although the use of teams is becoming more prevalent within organizations, the types of organizations such teams are a part of are quite varied. To be precise, there are countless examples of team research being conducted in contexts such as military, health care, academia, and manufacturing (Salas, Bowers, & Cannon-Bowers, 1995; Stokols, Hall, Taylor, & Moser, 2008; Weaver et al., 2014). Certainly, there are some factors of teamwork that translate regardless of the team’s context, for example, the need for effective communication. However, what effective communication looks like will differ across contexts. As such, there are unique features of the team’s context that should be taken into account (Johns, 2006) when determining what teamwork factors are most critical to a particular team. In addition, the tasks teams perform can vary and can also inform the teamwork needs of the team. Certainly, as stated by Nouri et al. (2013), “one cannot fully understand group performance without taking into account the nature of the taskbeing performed” (p. 741).

Accordingly, the topic of task analysis has received more attention over the past decade. For clarity, TTA is defined as “the process by which the major work behaviors and associated knowledge skills, and abilities (KSAs) that are required for successful job or task performance are identified” (Arthur, Edwards, Bell, Villado, & Bennett, 2005: 654). TTA as an intervention influences the team context or members of a team (i.e., the inputs). It is critical to conduct a task analysis, given the task performed by a team can have impacts which can be far-reaching in that it can shape which KSAs that are needed within a team and thereby shape who should be on the team, what staffing level is needed (i.e., TCo which is discussed in the next section), and how the job should be designed (Medsker & Campion, 1997). Likewise, the team’s task can impact how the team’s performance is evaluated (Arthur et al., 2005) and, in turn, how other interventions such as TT, coaching, and debriefs are designed (Arthur, Glaze, Bhupatkar, Villado, Bennett, & Rowe, 2012). The literature on task analysis is robust; however, the literature on TTA is sparser. Some of the literature on TTA has focused on the methodology for using certain techniques (e.g., team cognitive work analysis-Ashoori & Burns, 2013 and hierarchical task analysis-Annett et al., 2000) or the use of certain metrics, for example, team relatedness and team workflow to better differentiate between team tasks (Arthur et al., 2012). We organize our summary into the various themes that emerged as we reviewed the TTA literature stream.

TTA Theme 1: TTA requires an assessment of individual and teamwork behaviors/factors.

The work examining team tasks is built on a long history of research that has examined individual performance on work tasks. This research has unpacked the influence of certain factors on how tasks are accomplished. Researchers have considered factors such as importance, frequency, time spent, time to proficiency, criticality of task, difficulty of performing it, and consequences of error (Sanchez & Fraser, 1992) among other factors when assessing work behaviors. Accordingly, given that TTA built on the individual task analysis work, it is not surprising to see that some of the same features that were relevant for individuals will likewise be relevant for teams, namely, Bowers, Baker, and Salas’ (1994) creation of a team task inventory included dimensions such as importance to train, task criticality, task frequency, task difficulty, difficulty to train, and overall team importance. Likewise, Lantz and Brav (2007) detail a variety of task features that are also relevant to teams including demand on responsibility, cognitive demands, and learning opportunities.

That said, there are also factors that are only applicable when considering team tasks. For instance, Campion et al. (1996) provided evidence that the degree of dependency (i.e., interdependence) among team members impacts group processes. So, most of the factors that have been included within TTA focus on team member behaviors (i.e., how frequent the task is performed, how important it is, how difficult it is, and whether the team has to work on the task together). However, there is another subset of the TTA literature (i.e., cognitive task and work analysis) which has sought to pinpoint the knowledge and thought processes that may contribute to a team’s performance levels (Schraagen, Chipman, & Shalin, 2000). Research that focuses on unpacking team cognition (e.g., transactive memory systems), particularly understanding how team cognition changes over time, will inform how TDIs are implemented and developed (Kanawattanachai & Yoo, 2007; Lewis, 2004).

TTA Theme 2: the dynamic nature ofteam tasks mustbe accounted for in TTA.

As detailed earlier, researchers have started to coalesce in the way that team task features are measured in terms of the techniques used, the sources of information regarding the team’s task, and what features of the task are assessed. In our review of TDIs, we focused on one aspect, that is, the timing of when the TDIs we reviewed are typically implemented and discussed. In our review of the TTA literature, we found that such an intervention is largely discussed as a first step in terms of understanding a team, which is logical because a TTA provides an assessment of the team, the task, the context, and the team members. For example, Fowlkes, Lane, Salas, Franz, and Oser (1994) conducted a thorough examination of a training intervention with military helicopter and aircraft crews. To start, they conducted a task analysis to identify the specific actions that should be taken by aircraft personnel and then assessed the teams’ performance against such standard behaviors.

Conducting a task analysis at the beginning of the team’s life cycle is beneficial because it can allow for a more in-depth understanding of the team’s task which can be leveraged in determining what a team may need in terms of resources and/or development. Likewise, assessing the team’s task features at the beginning of the project may be in accordance with some of the seminal team effectiveness frame- works (e.g., the IPO framework) which consider task features as an input variable. However, such treatment implicitly assumes that the features of the team’s task do not change or evolve over time. This is unlikely to be the case for all teams. Specifically, the interdependence levels that may be observed at one point in time may not remain constant. In fact, based on changing environmental features or changes within the team, interdependence levels and other relevant task considerations may ebb and flow throughout the team’s life cycle. As such, we advo- cate for researchers to view TTA as a recurring pro- cess that may need to occur multiple times over the life cycle of a team.

Team Composition (TCo)

Definition and evidence assessment.

As mentioned earlier, TTA has often been discussed as the starting point for various other TDIs—training interventions in particular. However, TTA also in- forms discussions around how many individuals are needed for a particular task and what KSAs in- dividuals will need. In fact, Beersma, Hollenbeck, Humphrey, Moon, and Conlon (2003) found evidence that certain personalities within a team are better matches for certain task types. As such, TCo is a logical next TDI category to consider. TCo, the configuration of member attributes in a team (Levine & Moreland, 1990), has been a central component in examinations of organizational team effectiveness for several decades (Mann, 1959). However, within the current review, we examine TCo through the “lens” ofbeingaTDI andhowTCo as an intervention influences the inputs of the presented framework. As such, this provides unique insights as compared with those who have discussed TCo elsewhere (Mathieu et al., 2008).

The research on TCo has focused on surface-level (overt demographic characteristics) and deep-level (underlying psychological characteristics) variables and the relationship between these variables with team processes and outcomes. More recent research in the area of team science has focused on TCo in terms of diversity in knowledge and disciplines (i.e., deep-level constructs) as this is a major concern in terms of understanding its impact on resolving complex scientific questions. A meta-analysis that examined deep-level composition variables and team performance found medium (ρ = 0.37-agree- ableness; ρ = 0.33-conscientiousness) to small effects (ρ = 0.21-emotional stability; ρ = 0.26-preference for teamwork). Although additional research is needed to understand TCo as a TDI, in particular across the life of team, we have synthesized the current research into several themes.

TCo Theme 1: changes in team membership impact both team processes and performance.

Mathieu et al. (2008) discuss how TCo has been operationalized using various features of the team’s makeup. In particular, in the TCo literature, composition can be calculated by a mean value or summary index (Chen, Mathieu, & Bliese, 2004). Such an approach has been used with composition characteristics such as personality (LePine, 2003) and various KSAs (Cooke, Kiekel, Salas, & Stout, 2003), and these operationalizations of composition have been examined in relation to team processes and performance. Likewise, TCo researchers are also interested in the heterogeneity that may exist between team members on a multitude of features, including age (Kilduff, Angelmar, & Mehra, 2000); functions within the organization (Bunderson & Sutcliffe, 2002); as well as race/ethnicity, gender, tenure, personality, and education (Jackson, Joshi, & Erhardt, 2003; Kirkman, Tesluk, & Rosen, 2001; Mohammed & Angell, 2003).

Although the decision regarding how to operationalize composition should be based on the team’s task (e.g., a research team may benefit most from team members who are experts in distinct nonoverlapping knowledge domains), it is interesting to note that research is limited which has considered various operationalizations simultaneously, and when they do consider various composition features, it is typically performed with either multiple heterogeneity scores or merely summary indices of various constructs (Offermann, Bailey, Vasilopoulos, Seal, & Sass, 2004). Accordingly, it may be a fruitful direction for researchers to consider both summary indices and heterogeneity scores within single studies, given that Kichuk and Wiesner (1997) evidenced a multilayered story surrounding team compositional effects when considering both summary indexes and heterogeneity scores of team member personality.

TCo Theme 2: composition affects critical out- comes when it is considered at the initiation of a team.

The vast majority of studies that have considered TCo have done so with the mindset that TCo is set early in the team’s life cycle and will have downstream effects on team processes and ultimately on team performance. However, such a statement is not intended to suggest that the TCo literature is one dimensional. In fact, the TCo literature is quite diverse. For instance, work in this literature stream has looked at composition in a variety of ways including considerations of cognitive styles (Aggarwal & Woolley, 2013), general mental ability (Barrick, Stewart Neubert, & Mount, 1998), cultural diversity (Gibson & Saxton, 2005; Kirkman & Shapiro, 2001), and emotional intelligence (Jordan & Troth, 2004).

This diverse set of research regarding composition features has likewise been linked to a variety of team outcome variables including decision making effectiveness (Devine, 1999), customer service (Feyerherm & Rice, 2002), implicit coordination (Fisher, Bell, Dierdorff, & Belohlav, 2012), team viability (Resick, Dickson, Mitchelson, Allison, & Clark, 2010), task cohesion (van Vianen & De Dreu, 2001), and team performance (Woolley, Gerbasi, Chabris, Kosslyn, & Hackman, 2008). That said, although research on TCo has been framed in terms of providing indicators that are most salient when selecting individuals to a team, more research is needed which specifically examines the methodology for picking team membership. For instance, Colarelli and Boos (1992) examined sociometric and ability-based membership decisions and found that sociometric workgroups that were able to pick their own teammates reported higher levels of communication, coordination, cohesion, and satisfaction.

Team Work Design (TWD)

Definition and evidence assessment.

TWD may not be thought of as an intervention by some, as it focuses more on the environmental attributes and conditions under which teams work (Morgeson & Humphrey, 2008). However, when examining the elemental features of TDIs as previously presented, TWD can be used to address team needs in an intentional manner, it addresses the inputs of our framework, and as such provides a justification for the inclusion as a TDI in this review. Although the definition of work design broadly speaking refers to the structuring of and context in which tasks, responsibilities, and relationships are managed (Hackman & Oldham, 1976; Parker, 2014), at the team level this refers to a “defmition and structure of a team’s tasks, goals, and member’s roles; and the creation of organizational support for the team and link to the broader organizational context” (Morgeson & Humprhey, 2008: 46).

Work design in teams, as it refers to the changes in team context (i.e., tasks, activities, relationships, or responsibilities), has been found to play a key role in several team processes and outcome improvements. The principles of sociotechnical systems (STSs) influenced the design of group work (Parker, 2014; Parker, Morgeson, & Johns, 2017). In addition to the principles of STS, the job characteristics model (JCM) has also been the focus at the team level, meaning that jobs should be designed to have variety, autonomy, feedback, significance, and identity (Hackman & Oldham, 1976). By designing work with these characteristics in mind, individuals experience meaning, responsibility for outcomes created, and an understanding of the results from their effort (Paker et al., 2017). The parallel development of the STS approach and the JCM led to a focus on autonomy and the development of autonomous work groups (a.k.a. self-managing teams). As we are concerned here with developing teams, our lens for this review is primarily centered on the fact that team design is focused on the team’s needs. Related to the effects of team design as an intervention, there have been significant connections between elements of task interdependence and team empower- ment as predicting team performance and outcomes (Hollenbeck& Spitzmuller, 2012). More specifically, team design, through the use of autonomous work groups, has linked group autonomy with positive job attitudes, satisfaction, and commitment (Parker & Wall, 1998). Scholars have explained that when teams experience structures that are compatible with their preferences for getting work done (e.g., autonomy and appropriate degree of interdependence), the team will be more likely to maintain motivation to complete the task at hand (Hollenbeck, DeRue, & Guzzo, 2004). However, when teams experience design structures that do not meet their needs, they may become increasingly discouraged or may even leave the team (Park, Spitzmuller, & DeShon, 2013). Therefore, we next consider some of the trends across this literature to better understand its important influences.

TWD Theme 1: TWD needs to address both team and taskwork.

For teams, the consideration of work involves not only the actual task to be performed but also the teamwork processes and states that may be pivotal for team needs. This is particularly important as teamwork and taskwork may influence one another under different circumstances. For example, in considering task interdependence, one view suggests that when teams operate in tasks designed with higher degrees of interdependence, teamwork processes become that much more important in predicting outcomes (LePine et al., 2008). Alternatively, it has also been argued that teams may construct task interdependence as a function of the social interactions with other team members (Wageman & Gordon, 2005). That is, instead of being an objective indication as to the degree of task interdependency, interdependence is viewed as being driven by the social experiences. A team member who has built very strong social connections may perceive greater levels of interdependence than a team member who does not have the same degree of social connections and networks (Hollenbeck & Spitzmuller, 2012). Thus, from the view of considering work design as a TDI, it may be important to acknowledge that team members’ social relationships may facilitate and shape their perceptions of how their work is designed.

TWD Theme 2: TWD must address the balance of individuals and the whole team to achieve optimal effects.

Although work design research has typically focused on the impact of design on individual needs and outcomes, there has been a fair amount of attention to the team aspects as well, as we have discussed. However, the consideration of both team and individual work design is less understood but extremely important (Park et al., 2013). Park et al. note this in their review of the TWD literature in relation to team motivation, highlighting the idea that what is meant by team-level work design is not merely the aggregation of member characteristics. Wageman and Gordon (2005) argued that task in- terdependence is based on the values of the team. The example they provide is one based on team members who hold egalitarian values. People who hold egalitarian values tend to prefer conducting work using more cooperative processes and would prefer reward systems where rewards are shared. This example illustrates that individuals can change their work design to maximize outcomes (e.g., increased motivation and trust, and reduced conflict).

Team Charters (TChs)

Definition and evidence assessment.

Gersick (1988) and Feldman (1984) suggest that the first meeting of a team has lasting effects on how the team functions. The initial meeting jump starts the development of group norms and processes that aid a team’s performance. Research on TChs, an intervention which focuses on the development of team processes and in turn the development of emergent states (i.e., mediators), is relatively scarce and is primarily focused on student project teams. Research has reported that when student teams establish ground rules and clarify expectations by using TChs, teams are more satisfied and perform better (Aaron, McDowell, & Herdman, 2014; Byrd & Luthy, 2010; Mathieu & Rapp, 2009).

Sverdrup and Schei (2015) applied psychological contract theory to better understand the impact of TChs. Studies investigating psychological contracts have demonstrated significant effects on outcomes such as job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and organizational citizenship behavior (Bal, DeLange, Jansen, & Van Der Velde, 2008; Conway & Briner, 2009; De Vos, Buyens, & Schalk, 2003; Deery, Iverson, & Walsh, 2006; Schalk & Roe, 2007; Zhao, Wayne, Glibkowski, & Bravo, 2007). However, this examination is primarily focused on the re- lationship between employee and employer. Sverdup and Schei (2015) on the other hand apply psychological contract theory to the relationship between team members. Although a TCh is a written document, Sverdup & Schei highlight that whether a team contract is actually a tangible product “a team charter will…influence the content and perceptions of the psychological contract in the specific team” (p. 454).

Research on psychological contracts has highlighted that contracts can be transactional or relational, with transactional contracts referring to highly specific exchanges of limited durations and relational contracts are more open ended and relationship oriented with limited specification of how the contract will relate to performance requirements (Rousseau, 1995). The effectiveness of the psychological contract is also measured in terms of its features (Sels, Janssens, & van den Brande, 2004; Janssens, Sels, & Van den Brande, 2003). Sels et al. identified and validated six dimensions (i.e., tangibility, scope, stability, time frame, exchange symmetry, and contract level) of the psychological contract that they found to be strongly related to personal control and affective commitment. Sverdup and Schei focused their application of psychological contract theory by examining how contract breaches and fulfillment in teams may clarify what TChs should emphasize. In the following paragraphs, we highlight two themes that emerged when reviewing the TCh research.

TCh Theme 1: TChs influence processes and emergent states by establishing mutual expectations.

TChs are meant to provide a team with an opportunity to clarify expectations and obligations to the team and the team outcome(s). Sverdup and Schei (2015) highlighted the need of developing expectations and obligations that are linked to work effort and quality. Moreover, they found that these elements of a charter (in conjunction with defining how breaches and violations were to be handled within the team) allowed for healthy team development to occur throughout the team’s life cycle. Specifically, teams engage in a sensemaking process that allows for the team to handle the breach with patience instead of attaching a violation to the behavior. This finding further develops our understanding of how TChs actually function. In particular, the purpose of the TChs is to influence processes and emergent states by eliminating misunderstandings and clarifying how the team should function.

TCh Theme 2: team charter content requires critical independent and team consideration.

The content of the TChs is meant to map onto effective teamwork characteristics and behaviors (i.e., processes and emergent states; Hunsaker et al., 2011). Some common content addressed in TChs includes purpose/mission statements, operating guidelines, behavioral norms, and performance management processes. Mathieu and Rapp (2009) found a positive effect of using TChs which included a section that individuals prepared independently. The content of the charter affords the team the opportunity to engage independently and interdependently to develop their team-level norms and ground rules.

Team Performance Monitoring & Assessment (TPMA)

Definition and evidence assessment.

Although TDIs such as TChs influence the processes that teams engage in and TCo influences the team members of the team, teams can also benefit from intervening in the form of receiving periodic updates of their performance status. TPMA involves the capturing of both individual and team levels of processes and performance, preferably from a dynamic lens where continual monitoring is available throughout a performance episode (Cannon-Bowers & Salas, 1997). As indicated within the goal-setting literature, this monitoring of team goals will aid teams in more effectively achieving their goals (Locke & Latham, 2002).

The research on TPMA is not particularly sparse; however, it is heavily intertwined with the TT literature because the focus is on the measurement of performance. The literature would benefit from some distinction between performance monitoring and assessment and TT with a focus on team performance over time. An important consideration for team performance monitoring involves carefully attending to what is being monitored. As the most often facet of team, outcomes can be separated into two distinct sets: performance and affective outcomes (Hackman & Morris 1975). Team performance outcomes are typically denoted by the assessment of the team’s accomplishment of assigned goals. The measurement of these outcomes can range from a simple checklist of predefined goals the team was assigned to accomplish to a supervisor’s assessment of a team’s accuracy and quality of work performed (Rosen et al., 2008). We next offer a summary of some of the major themes regarding TPMA as an intervention.

TPMA Theme 1: team performance monitoring is multifaceted and multilevel.

Although providing teams with an assessment of their current team performance status is critical, it can be challenging to assess all components of team performance, especially the subjective nature of team processes (Cannon-Bowers & Salas, 1997). For example, the assessment of team performance outcomes is typically related to the accomplishment of task/team goals. Conversely, and more challenging, affective outcomes target how the team feels regarding their teamwork experience. Some prominent affective outcomes include the team’s willingness to work together in the future, team satisfaction, and team member trust (Mathieu et al., 2008). Although some may consider affective outcomes less important than performance outcomes, they have critical implications for teams that plan to perform together in the future.

By ensuring that teams are provided with or are able to monitor information regarding their current status both in terms of processes and performance at multiple points in time, they can continually adapt and adjust based on such feedback (Dickinson & McIntyre, 1997). To address this, several different measurement approaches have been developed. This includes checklist style feedback instruments (e.g., behavioral observation scales, behaviorally anchored rating systems) that track the degree to which team members are performing both on processes and outcomes (Salas & Cannon-Bowers, 2001).

TPMA Theme 2: performance monitoring and assessment can (and often should) be implemented with multiple mechanisms.

To fully capture the multilevel and multifaceted nature of performance, monitoring and assessment of teams most optimally will combine multiple mechanisms. Indeed, Dickinson and McIntyre (1997) argued that it takes a team to measure a team accurately. This argument has two implications. First, teams are constantly engaging in simultaneous dynamic processes; thus, it can be difficult for any single individual to keep track and record all the actions of a team (Wiese, Shuffler, & Salas, 2015). For example, if using external raters [i.e., subject matter experts (SMEs)] to observe team interactions, having several observers available to measure a team’s processes and performance can help ensure that this wealth of information is adequately captured. Secondly, use of a single source (e.g., only team members and only supervisors) for ratings could result in biased/deficient/contaminated measurement of team variables. Therefore, it is recommended that a diversity of measurement sources is used. The number and diversity of sources one uses can be affected by a number of factors (e.g., the number of team members, complexity of the task, and the amount of interdependence required for task completion).

More recently, measures of processes that can be embedded in performance situations have become of interest to researchers and practitioners alike (Shuffler, Salas, & Pavlas, 2012). For example, the scales used in the Targeted Acceptable Responses to Generated Events or Tasks (TARGETs) methodology allow even relatively novice observers to appropriately rate team behavior and provide targeted feedback (Fowlkes et al., 1994). These rating scales are developed with the assistance of SMEs and target-specific observable behaviors, exhibited knowledge, and critical skills. By implementing tools such as TARGETS and other automated or simulation-based tools, it may be easier to reduce the human error element of performance management, providing more accurate and in turn more useful information back to teams (Kozlwoski et al., 2015). Indeed, this type of event-based measurement approach (e.g., TARGETS) has seen remarkable success in military teams and other domains (Fowlkes et al., 1994).

Team Debriefing (TD)

Definition and evidence assessment.

Team de-briefs, or after action reviews (AARs) as termed in military contexts, are a form of TDI used for learning and improving from team outcomes, through both individual- and team-level reflection and learning. The goal of a debrief is to have individuals and teams engage in an activity of reflection by asking a series of questions for them to consider their most recent experience (i.e., simulated or real) and discuss lessons learned. In other words, the focus of a debrief is the team’s outputs and the processes/emergent states that may need attention to change future outputs. A key characteristic of debriefs is that this reflection must be conducted in a safe environment, absent fear of repercussion or retaliation, to be effective. As such, TD are defined as interventions that encourage reflection and self-discovery, target potential opportunities for improvement, and as a result improve the quality of experiential learning which thus improves team inputs, processes, and outcomes (Tannenbaum & Cerasoli, 2013).

The research on TD cuts across many disciplines (e.g., aviation, military, medicine, and education) and in its earlier forms was more atheoretical. Tannenbaum and Cerasoli (2013) delineated that debriefs are differentiated from other TDIs by the following elements: active learning, developmental intent, specificity, and multiple information sources. Active engagement of the individuals/teams involved in a performance episode (Darling & Parry, 2001; Ron et al., 2002) is necessary for reflection to be considered a true debrief. Active engagement in reflection activities, such as debriefs, provides the team with an opportunity to think deeply about an event, engage in discovery (Eddy, D’Abate, Tannenbaum, Givens-Skelton, & Robinson, 2013) at the individual and team level, and plan for future performance. Debriefs must also have intentions to develop the persons involved in the work and their future performance. Another defining feature is that debriefs should be focused on specific events. The focus on specific events helps teams and in- dividuals develop future action plans and improve motivation (Locke & Latham, 1990, 2002). Multiple information sources are essential for an intervention to be considered a debrief because it provides more sources of feedback (Kluger & DeNisi, 1996).

Research and implementation focused on TD have increased in the last several decades. A meta- analysis conducted by Tannenbaum and Cerasoli (2013) found that debriefs resulted in an average 25% improvement compared with control conditions (d = 0.66). Thus, although the evidence base for team debriefing is still relatively young, there is a solid foundation in terms of the impact of debriefs as a potential intervention for addressing team out-puts, so that future teamwork episodes may be more effective. Furthermore, debriefs are readily used in conjunction with TT, to gauge knowledge building after completed training exercises. Accordingly, assessing the efficacy of their integration with one another is an important consideration in relation to our framework. In our review of the literature, we identified several themes that inform our understanding of debriefs as a TDI.

TD Theme 1: there is a distinct différence between feedback and debriefs.

Ellis and Davidi’s (2005) work on debriefs has pointedly acknowledged the difference between debriefs and similar interventions such as feedback. Debriefs (and AARs) are considered learning based organizational interventions. Ellis and Davidi (2005) describe that the action of debriefing provides learners with an opportunity to engage in self-explanation and data verification and that feedback is a by-product of debriefing. More formally, feedback is information provided to an individual. From the perspective of a one-directional traditional model of feedback between a leader and subordinate, it is the influential figure, or leader, who provides feedback to the subordinate about their performance. Debriefs not only focus on the reflection of the outcome of a work period but also the processes involved with getting to that outcome.

Several studies have investigated the effectiveness of including feedback with debriefs (Oden, 2009). In a study that compared the impact of debriefing only and audio-visual feedback plus debriefing, Dine, Gersh, Leary, Riegel, Bellini, and Abela (2008) found that performance outcomes on a CPR task did change, whereby there were significant improvements in performance when debriefing was combined with feedback. In a similar study, conducted by Edelson et al. (2008), greater improvements in CPR performance resulted when feedback was coupled with a debriefing intervention.

TD Theme 2: debriefs inherently change the structural knowledge of a task.

An important stream of research on debriefs assesses the impact of the content of the debriefs. Ellis and Davidi (2009) examined the advantage of drawing lessons from failures and success during debriefs. The results indicated that when participants debriefed and examined their failures and successes, their performance on tasks that followed improved significantly. Qudrat-Ullah (2007) reported results that when individuals engaged in a debriefing activity they not only improved on task performance but also improved their structural knowledge of the task, developed heuristics to be used in the task, and were able to reduce their decision time. In a team-based study conducted by Smith-Jentsch, Cannon-Bowers, Tannenbaum, and Salas (2008), the use of a guided debriefing activity was compared with the use of a traditional debriefing activity that was not well participated and followed the task chronologically. The study’s results indicated that the use of an expert model-guided debriefing activity developed more accurate mental models of the teamwork and im- proved teamwork processes and outcomes.

TD Theme 3. Debriefs are best used after a criticai period of team performance to encourage future team learning.

Given the nature and purpose of a debrief, they are inherently designed to occur after teams have worked together for a period of time, but they may be best used following a critical period of performance where subsequent skill development is most needed for future team effectiveness. The timing of debriefs in the literature has been primarily focused on the application of the debrief as it is embedded in a training program or post-simulated events and even in unique cases embedded within an actual organization. For example, Bethune et al. (2011) implemented a prebrief-debrief model into the surgical theater and found that briefings specifically highlighted potential problems, improved team culture, and led to organizational change. Debriefings unfortunately were not closely adhered to because it was difficult for all team members to attend, given other commitments and work load. What resulted was that the prebrief not only provided the team with an opportunity to discuss the upcoming patient case but team members also used this opportunity to integrate a debrief based on previous cases.

Robertson et al. conducted a study in which a pre-post test design was used in which a training program modeled after a crisis resource management had included a 30-minute video-based structured debrief as part of the training program. The study resulted in significant changes pre and post training to outcome variables (e.g., individual and team performance, and competence in handling obstetric emergencies). Although the research on debriefs has focused on the use of a debrief intervention at the end of a performance episode or embedded at the end of a training intervention, we believe research is needed that focuses on how the use of debriefs evolves over time.

Team Building (TB)

Definition and evidence assessment.

TB is a commonly applied intervention in organizations that focus on team processes and outcomes and can come in many forms that can range widely in terms of their reliance on scientific evidence (e.g., outdoor ropes courses and classroom-based activities; Klein et al., 2009). From a scientific perspective, TB originally began as a group process intervention designed to improve interpersonal relations and social interactions and has evolved to now include the achievement of results, meeting goals, and accomplishing tasks (Klein et al., 2009). The typical model of a TB intervention, if grounded in theory, is one that incorporates one or more of four main foci: goal setting, interpersonal relations, role clarification, or problem-solving. Although there may be variance in how TB interventions are designed, effective TB typically follows a structured developmental process (Salas, Priest, & DeRouin, 2005). This includes incorporating team members into the intervention process, ensuring that activities specifically reinforce one or more of the four foci, and providing a clear means for evaluating the activities and structure after implementation (Dyer, 2007; Payne, 2001).

In terms of the evidence base, the quality of research ranges widely, as not all TB efforts follow this prescribed structure. However, the most recent meta-analysis (Klein et al., 2009) demonstrates that when this structure is imposed, TB is effective for improving team outcomes (ρ = 0.31, omnibus test), and more specifically, the meta-analysis showed that TB was more effective for affective outcomes (ρ = 0.44) and process outcomes (ρ = 0.44); more effective when the component of focus was role clarification (ρ = 0.35) and goal setting (ρ = 0.37), and for larger teams (ρ = 0.66). Although we have data that do indicate that TB is effective, we still need to know more about this TDI, given its commonly misattributed role as a “catchall” for describing anything loosely classified as a TDI (Shuffler et al., 2011). We next identify several critical themes that provide insights regarding this often-misunderstood TDI.

TB Theme 1. TB demonstrates the benefits of a multifaceted intervention approach.

Setting it apart from some of the other TDIs that are primarily focused on a single strategy or focus, TB has an inherent multifaceted approach. Although several iterations of the components of TB have developed over the years, as mentioned earlier, TB is currently viewed as a four-pronged approach, including (1) a goal-setting model, (2) an interpersonal model, (3) a role clarification model, and (4) a problem-solving model. Each of the four current components addresses a different purpose of TB.

The emphasis of the goal-setting approach is on setting objectives and developing individual and team goals. During this type of TB, team members become involved in actively planning how to identify and achieve goals (Salas, Rozell, Mullen, & Driskell, 1999). TB interventions, which focus on the interpersonal relations component, emphasize increasing teamwork processes and emergent states, such as mutual supportiveness, communication, and the development of team affect (Tannenbaum et al., 1992; DeMeuse & Liebowitz, 1981). Role clarification emphasizes increasing communication among team members in terms of their respective roles as a part of the team (Salas et al., 1999). Finally, the problem-solving approach to TB is perhaps the most unique, as it subsumes aspects of all the components described by Beer (1980). This type of intervention promotes team synergy through encouraging team members to practice setting goals, developing interpersonal relations, clarifying team roles, and working to improve organizational characteristics through participating in problem-solving tasks. Although each of these components can be beneficial to helping support teams, it is when they are combined together that they are most effective, as noted by Tannenbaum et al. (1992) in their review of the TB literature.

One reason that this approach may be especially useful is that it addresses unique yet complementary team needs and problems; for example, the incorporation of role clarification and interpersonal skill development may make it easier for team members to determine what roles they have, how these roles may fit together, and based on that role understanding, who they may need to get along with as a function of their roles. This may encourage members who have highly interdependent roles to focus on working together in developing interpersonal connections and relationships, which may be more successful than having all team members spending concerted effort on developing relationships where they may not matter. Although not always implemented together, these four complementary approaches do provide some insight as to the value of such an approach.

TB Theme 2: TB is most effective for affective-based team needs.

The meta-analytic investigation conducted by Klein et al. (2009) found that TB interventions were most effective when the targeted team outcome was affective in nature. For example, TB interventions that improved trust between team members or confidence. In addition, results of the meta-analysis also showed that TB was effective when the target of the intervention was to improve process outcomes (i.e., coordination, communication, and adaptability). However, the strongest and most consistent effects appear to be the more affectively driven states that are critical to teams, such as trust, cohesion, psychological safety, and collective efficacy (Schwarzmann, Hease, & Tollefson, 2010).

It is important to note that following implementation, TB exercises are often evaluated only on the basis of affective or other subjective reactions, which may have implications in terms of why this connection exists between TB and affective outcomes (Sims et al., 2006). TB is often judged on whether team members believed that the training was valuable or perceived as effective in changing team norms and processes. Therefore, at times it can be difficult to determine if TB exercises are truly effective at improving team processes and performance. However, as Klein et al. (2009) noted in their meta-analysis, there does seem to be a theoretically and empirically based value add in terms of the different aspects of TB working together to specifically address the affective needs. A critical point that Klein et al. highlight in the interpretation of their results is that a TB intervention must focus on what the team needs for effective performance. If trust is of utmost importance to the success of the team in the context in which they work, then TB intervention should focus on building trust and applying the lessons learned and skill development from the TB intervention to the context in which the team works.

Team Training (TT)

Definition and evidence assessment.

Salas and Cannon-Bowers (1998) appropriately define TT as a “set of theoretically based strategies or instructional processes, which are based on the science and practice of designing and delivering instruction to enhance and maintain team performance under different conditions” (p. 254). The purpose of TT is for team members to understand, practice, and obtain the KSAs required for effective performance while receiving feedback. Furthermore, TT provides an opportunity for teams to identify teamwork deficiencies and learn skills to address these deficiencies. Similar to individual training, TT involves identifying the optimal combination of tools (e.g., TTA), delivery methods (e.g., practice- based, information-based, and demonstration-based), and content (e.g., knowledge, skills, and attitudes; Salas & Cannon-Bowers, 1998).

Of all the research on TDIs, the evidence for TT is perhaps the strongest. In a meta-analysis by Salas et al. (2008), TT was found to account for approximately 12 to 19 percent of the variance in the examined outcomes (i.e., cognitive, affective, process, and performance), with TT TDIs being more effective for team processes than for the other outcome types. Meta-analytic findings also uncovered several moderators; that is, the TT and team outcomes relationship was moderated by membership stability (ρ = 0.48 and ρ = 0.54, intact teams that underwent training improved the most on process and performance outcomes, respectively), large teams (ρ = 0.50, when team performance was the dependent variable), and small teams (ρ = 0.59, when team processes were the dependent variable). As there are several meta-analyses on TT (Hughes et al., 2016; Salas et al., 2008), as well as numerous detailed descriptions of the different types of TT, we focus on providing a high-level summary of the extensive base of TT evidence.

TT Theme 1: TT can be structured in a multitude of ways while stili addressing the overall goal of teamwork skill development.

There are a number of strategies that have emerged in the literature of TT, including team self-correction, cross-training, and team coordination training. For example, cross-training is a TT strategy which trains each team member the duties and responsibilities of their teammates. The goal of this training strategy is to develop a shared understanding of the overall functioning of each team member’s role (Blickensderfer, Cannon-Bowers, & Salas, 1998). Team coordination training targets the improvement of a team’s shared mental model framework. One specific TDI which targets the team’s ability to conduct effective after-action-reviews is guided team self-correction. Guided team self-correction is a team development strategy designed to enable teams to enhance their performance. Team self-correction involves developing the team’s ability to diagnose their behavior in terms of specific topics that should be discussed during debriefings and how they conduct the discussion of the specific topics identified (Smith-Jentsch, Zeisig, Acton, & McPherson, 1998). It is expected that teams that engage in this type of team strategy are able to collectively make sense of their environment and to develop a shared vision for how they should, as a team, proceed in the future.

Research on guided team self-correction has demonstrated that it is able to improve both taskwork and teamwork factors. The theoretical underpinning of guided team self-correction is mental model theory. Mental model theory suggests that when team-mates hold similar cognitive representations of their taskwork and teamwork, they are better able to anticipate one another’s needs and actions, better able to engage in more efficient task strategies, better able to engage in sensemaking as a team, and better able to manage unexpected events during a team’s performance cycle (Smith-Jentsch et al., 2008).

Given the breadth of literature in this area, we will not fully go in-depth on all of the different forms of TT here as they have been defined and described elsewhere (Hughes et al., 2016; Salas et al., 2008). However, this further emphasizes the significant need for careful planning and selection to ensure that the most appropriate form of TT is used for a given team. In addition, much like with the multifaceted nature of TB, the multifaceted nature of TT also highlights the potential value in both the integration of multiple TDIs, as well as the need for attention to when each of these different training programs may have the strongest impact on a team’s development and growth over time.

TT Theme 2: TT is an effective multifaceted TDI, addressing numerous critical team outcomes and processes.

These training strategies have shown significant positive impacts on team cognitive, affective, process, and performance outcomes (Salas et al., 2008). One of the most common types of team coordination training is that of crew resource management (CRM), which is designed to improve teamwork by teaching team members to use all available resources (e.g., information, equipment, and people) through effective team coordination and communication (Salas, Burke, Bowers, & Wilson, 2001). CRM has been successfully used in many industries, especially aviation, health care, and the military.

Team self-correction focuses on teams exploring their processes and performance. When teams are able to explore their performance (i.e., affect, behavior, and cognition), they will be better able to develop a larger repertoire of knowledge (i.e., taskwork or teamwork knowledge) that they can choose from in the future. The creation of this larger repertoire of knowledge develops a more adaptable team. Therefore, if the team is faced with a future nonroutine task, teams that are more adaptable will be more capable of adjusting to these emergent situations and better able to manage, if not bypass, any role overloads. Given the complex and dynamic nature of modern work environments, adaptability is a desirable characteristic of individuals and teams (Maynard, Kennedy, & Sommer, 2015; Smith, Ford, & Kozlowski, 1997).

Team Coaching (TCa)

Definition and evidence assessment.

Although it is clearly effective, some have suggested that TT alone is not sufficient to see behavior changes, and instead, TCa is likely to garner enhanced behavior changes (Showers, 1987) as coaching is a means to sustain the results of various TDIs (Neuman & Cunningham, 2009; Scott & Martinek, 2006). As a result of this belief, organizations have increasingly made substantial investments in means by which to develop managerial coaching (e.g., Redshaw, 2000). TCa as a concept was primarily introduced by Hackman and Wageman (2005). In presenting their theory of TCa, these authors suggest (as we do here) that TCa is an intervention that is likely to be impactful at various points along the team’s life cycle (i.e., at the beginning, the mid-point, and the end of the project). As suggested by Hackman and Wageman (2005), TCa is the “direct interaction with a team intended to help members make coordinated and task-appropriate use of their collective resources in accomplishing the team’s work” (p. 269).

In our search of the TCa literature, we found a stream of practical research that described case studies in TCa and applied examples of TCa as a training intervention. However, the science on TCa is lacking rigorous training evaluation with quantitative and qualitative methods, in addition to meta-analytic or systematic reviews of the literature. Although there are some exceptions, particularly in the health-care industry, more research is needed to understand the effect TCa has on sustaining TT results.

Coaching is an intervention that is often coupled with other forms of TDIs. In particular, some have posited that coaching best follows training interventions so that it can occur as individuals are implementing the skills learned during such training (Scheuermann et al., 2013). For instance, Shunk, Dulay, Chou, Janson, and O’Brien (2014) coupled coaching with a multifaceted intervention that included TB, checklist development, and training intervention components that were collectively focused on the use of huddles within a health-care clinic setting. Specifically, health-care teams who were assigned a “huddle coach” were instructed on how to use the huddle checklist and served as observers of the team’s huddle. Similarly, Morgan et al. (2015) examined an intervention of orthopedic surgery teams that included CRM teamwork training and six weeks of on-the-job coaching, in which their joint effect demonstrated a positive impact on team nontechnical skills, as well as enhanced compliance with time-outs.

Likewise, Wilson, Dykstra, Watson, Boyd, and Crais (2012) compared interventions that included training and coaching compared with an intervention that just included training and found evidence that those that received both the training and coaching interventions had the largest positive change in their use of team planning and monitoring practices, as well as the largest amount of student goals attained. Interestingly, Sargent, Allen, Frahm, and Morris (2009) also linked training and coaching, but do so in a different way, namely, they examined the process by which teaching assistants received training on how to be able to effectively coach student teams. They conducted a quasi-experimental design comparing the performance of teams who were coached by teaching assistants that received the training versus those who did not receive the training. Their results point to the fact that coaches who were trained had teams that functioned better, had higher levels of productivity, and felt their coach was more effective as compared with teams whose coaches were untrained.

TCa Theme 1: results heavily depend on who is serving as the coach.

Based on our review of the TCa literature, one of the first big takeaways is the fact that who the coach is has a varied answer. For example, some have argued that it is important that the coach be an external resource because having an external coach work with the team may enhance team functioning. In part, this sentiment is based on the belief that an external coach can focus on how the team is actually working because in comparison to the team members and leader, an external coach is less likely to be preoccupied with team outcomes (Reich, Ullmann, Van der Loos, & Leifer, 2009) and may be more objective (King & Eaton, 1999). For instance, Shunket al. (2014) provide a study of the use of huddle coaches within a health-care context. In particular, these coaches were primarily physicians who received faculty development on the use of huddles and then the coaches observed subsequent team huddles and provided feedback on underlying teamwork skills. The results of this coaching intervention appeared beneficial as study participants felt that the efficiency and quality of patient care improved as a result of this TDI.

By contrast to this external view of the coach, others have approached the concept of coaching in terms of actions or behaviors that the team’s leader should provide. For instance, Rousseau, Aube, and Tremblay (2013) asked team members to evaluate their supervisors’ coaching behaviors (i.e., he/she sets expectations, encourages us to find our own solutions, and points out areas where we need to improve) and found that teams that had leaders who provided these coaching behaviors were more innovative as a result of the impact that coaching had on team goal commitment and support for innovation. Wageman (2001) also assessed the impact of internal leader coaching behaviors but categorized coaching behaviors as either positive (i.e., provides cues and informal rewards for self-managing behaviors and problem-solving consultation) or negative (identifying team problems and leader task intervention). In her study of Xerox service teams, Wageman (2001) evidenced that positive coaching behaviors exhibited by the leader was positively related to team self-management and quality of group processes, whereas negative coaching was negatively related to self-management and work satisfaction.

TCa Theme 2: a coach can serve in multiple functions to address different team needs.

In addition to who the coach is being an area of disagreement within the literature, it is also interesting to note that what the coach actually does for the team is also less than clear within the literature. In fact, Carr and Peters (2013) argued that “TCa has been loosely defined and used as an umbrella term that includes facilitation, TB, and other group process interventions” (p. 80). Specifically, some have contended that the coach can provide teams with assistance “that ranges from problem solving to moral support” (Reich et al., 2009: 205). In their seminal work on TCa, Hackman and Wageman (2005) outline three primary coaching intervention functions: motivational, which is focused on minimizing social loafing and increasing shared commitment; consultative, which pushes members to create work processes that are aligned to task features; and educational, designed to enhance team members’ knowledge, skills, and abilities. Clutterbuck (2007) built on the work of Hackman and Wageman (2005) and proposed that prominent coaching principles include reflection, analysis, and motivation to change. Some have suggested that coaching is a stage-driven process with specific steps around observing, acting, reflecting, and evaluating, (Wilson et al., 2012).

By contrast, others have postulated that internal coaches need to exhibit behaviors such as “(1) soliciting and providing feedback, (2) empowering employees, (3) broadening employees’ perspectives, (4) transforming ownership, (5) communicating expectations, and (6) finding how employees’ work and tasks fit into the big picture” (Hagen, 2010: 793). However, although theoretical pieces have outlined these various ingredients of TCa, research has not adequately addressed these steps. In part, this may be due to the general tendency of TCa studies to not examine this form of TDI longitudinally. Granted, there are exceptions to this statement. In particular, Weer, DiRenzo, and Shipper (2016) examined 714 managers and their teams over a 54-month period oftime and examined two categories of coaching behaviors—facilitative vs. pressure-based coaching. They provide evidence of the positive impact that facilitative coaching has on team commitment, and in turn, team effectiveness. By contrast, pressure-based coaching negatively influenced team commitment, and thereby team effectiveness. In addition, Alken, Tan, Luursema, Fluit, and van Goor (2013) provide a roadmap for how future research could be designed to examine what team coaches actually do, namely, these authors coded the communications of instructors who were assisting (and coaching) 11 surgical teams. They outline that additional research is needed to understand how specificity of a coach’s communication may influence learning outcomes of learners.

TCa Theme 3: the target ofwho should receive the coaching can vary.

Related to what the coach does, another theme that emerged during our review is related to the target of the coaching. Specifically, much of the literature has focused on coaching interventions that are targeted to the team as a whole. This would be aligned with certain definitions of TCa which specifically state that the coach works with the entire team (Hawkins, 2011). This approach is also assumed by the various studies that have not actually investigated TCa interventions but instead have examined the team member’s collective perception regarding the internal team leader’s coaching behaviors (Liu et al., 2009; Reich et al., 2009; Rousseau et al., 2013). However, several researchers (Hawkins, 2011; Wageman, Nunes, Burruss, & Hackman, 2008) have alluded to the fact that it may be beneficial for an external team coach to focus their attention on the internal team leader to enhance the coaching capabilities that exist within the team. As such, future research may want to examine more closely coaching interventions that are primarily focused on shaping behaviors of the team leader and through the actions of this particular person, ultimately shape the entire team’s dynamics and performance. Similarly, more work could explore the impact of peer coaching within teams as the limited work in this area has demonstrated promising results (Hackman & O’Connor, 2005).

Team Leadership (TL)

Définition and evidence assessment.

TL represents a key mechanism by which teams can be effective and, as such, has been broadly studied in terms of its impact (Zaccaro, Rittman, & Marks, 2001). From a TDI perspective, we focus specifically on those interventions targeted at improving TL, to bound our review. Team leaders, whether one or several individuals, are responsible for defining team directions and for organizing the team to achieve progress toward their goal (Hackman & Wageman 2005). The literature on TL interventions often takes the perspective that leadership is con- sidered social problem-solving and, as such, leaders must be prepared to determine when problems exist that may prohibit the team from performing their goals, create solutions to these problems, and implement solutions (Mumford et al., 2003; Zaccaro et al., 2001). The functional TL literature has focused on team needs and how leaders can fulfill those needs by engaging in particular behaviors (Hackman & Wageman 2005; Morgeson, DeRue, & Karam, 2010).

The literature that addresses how to intervene and improve TL is quite extensive, with several examples of meta-analytic investigations on the topic. In a study with consulting teams, Carson et al. (2007) make an important contribution to understanding TL by highlighting that multiple team members can make contributions. Moreover, they highlight that the internal context in which teams operate are important determinants of TL. Burke, Stagl, Klein, Goodwin, Salas, and Halpin (2006) focused on identifying what behaviors may be most vital and, therefore, most likely to inform the content of TDIs for TL, finding that person-focused behaviors were related to perceived team effectiveness (ρ = 0.36), team productivity (ρ = 0.28), and team learning (ρ = 0.56). In our review of the literature, we identified several themes that connect the research base for TL interventions.

TL Theme 1: shared leadership is a particularly effective intervention for enhancing team outcomes.

As of late, the TL research has focused intensely on how sharing TL may impact team out-comes, especially what can be done to prepare team members to share leadership responsibilities as needed. Seers et al. define shared leadership as “the extent which more than one individual can effectively operate in a distinctively influential role within the same interdependent role system” (2003: 79). Wang et al. (2014) conducted a meta-analysis in which they examined the relationship between shared leadership and team effectiveness. They discovered that TL that focuses on change and development (Contractor et al., 2012) is more beneficial to teams. That is, sharing in leadership functions that are oriented toward change (e.g., visionary leadership functions or innovative leadership functions) are more effective, in terms of outcomes, than sharing in traditional leadership functions among multiple team members. Wang et al. (2014) also reported meta-analyzed findings that demonstrated shared leadership are more related to attitudinal and behavioral outcomes as compared with performance measures.

Nicolaides et al. (2014) in their meta-analysis on shared leadership and team performance found that shared leadership explains unique variance in team performance more than that of vertical leadership. Specifically, shared leadership explained an additional 5.7 percent (p < .01) of the variance in team performance beyond vertical leadership. However, much more needs to be investigated to understand how shared leadership and vertical leadership operate together (Conger & Pearce, 2003) and across the team’s life cycle.

TL Theme 2: task type is an important moderator ofthe TL and team performance relationship.

Although we acknowledge the influence that leadership has on team outcomes, it is important to consider what moderators may exist in this relationship. Wang et al. (2014) examined the moderators of TL and performance and found that the task is a moderator to the relationship between shared leadership and outcomes. When teams work on tasks that are highly interdependent and knowledge based, a stronger relationship between shared leadership and outcomes was found. However, D’Innocenzo, Mathieu, and Kukenberger (2016) in a meta-analysis of the different forms of shared leadership and team performance relations found that complexity of team tasks related negatively to the magnitude of shared leadership-performance relations.

In another meta-analysis on shared leadership and team performance, Nicolaides et al. (2014) found that when task interdependence was high, a strong correlation between shared leadership and team performance was produced. Burke et al. (2006) also examined the moderating influence of task on team performance and found that their results do suggest that leadership in teams is more impactful to team performance when task interdependencies are higher; however, the authors do note that their finding was based on a small number of effect sizes and should be interpreted with caution.

TL Theme 3: team leaders must provide different forms of support over time to meet changing team needs.