Abstract

Background:

This study examined how risk perceptions and social norms around e-cigarettes are associated with susceptibility (i.e., openness to using the product in the next 12 months) of e-cigarettes and smoking among adolescents.

Methods:

We analyzed data from a 2016 representative survey of 8718 middle-school students in Mexico. The study sample was restricted to students who had tried neither e-cigarettes nor cigarettes, (n=4471). Students reported on the risks of e-cigarettes compared to cigarettes, and product-specific norms were measured by assessing current use by family members, at least one close friend, and, for e-cigarettes, by perceived societal acceptability of use (i.e., acceptability among people in general). Adjusted prevalence ratios (APR) were estimated using generalized estimating equation (GEE) models that regressed e-cigarette societal acceptability on study variables. Adjusted GEE models also regressed susceptibility for each product on study variables.

Results:

Susceptibility to both e-cigarettes and smoking was higher among students who reported that their family and friends used only cigarettes or both products when compared to students whose family and friends did not use either of these products. Friend use of e-cigarettes was associated with e-cigarette susceptibility (APR= 1.33), but not smoking susceptibility. Students who perceived that e-cigarettes were less risky than smoking were more susceptible to e-cigarette use (APR=1.45). The association between e-cigarette susceptibility and friend or family use was not mediated by societal acceptability.

Conclusions:

E-cigarette use among family and peers appears associated with susceptibility to use e-cigarettes in a way that is similar to the patterns found for cigarettes. However, the influences appear somewhat specific to the type of product that network members use.

INTRODUCTION

Electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) have been on the rise globally (Bhatnagar, Whitsel, & Ribisl, 2014), since first being introduced to the European and American market in 2006 and 2007, respectively (Noel, Rees, & Connolly, 2011). E-cigarettes are battery-powered devices that typically contain a liquid with nicotine that is aerosolized and inhaled by the user (Gostin & Glasner, 2014; Grana, 2013). These products are advertised as an advanced technology that is a relatively safe alternative to smoking (Berg et al., 2015; Gostin & Glasner, 2014; Grana, 2013). Indeed some research suggests that adolescents believe e-cigarettes to be safer, less addictive (Berg et al., 2015; Gorukanti, Delucchi, Ling, Fisher-Travis, & Halpern-Felsher, 2017; Margolis, Nguyen, Slavit, & King, 2016; Noland et al., 2016; Roditis, Delucchi, Cash, & Halpern-Felsher, 2016) and more socially acceptable (Berg et al., 2015; Gorukanti et al., 2017; Noland et al., 2016; Trumbo & Harper, 2015) than cigarettes. Moreover, adolescents who perceive e-cigarettes to be less risky than smoking (Choi & Forster, 2013; Goniewicz, Lingas, & Hajek, 2013; Margolis et al., 2016; Thrasher et al., 2016) and who find them socially acceptable appear more likely to experiment with and become current users of e-cigarettes (Gorukanti et al., 2017; Noland et al., 2016). However, most studies to date have taken place in high-income countries where e-cigarettes are legally available. Furthermore, studies that have evaluated e-cigarette norms and their association with e-cigarette and smoking behavior have not evaluated both injunctive and descriptive norms. This study aimed to examine whether tobacco product specific social norms and risk perceptions are differentially associated with susceptibility to e-cigarettes and cigarettes.

The few previous studies that have examined e-cigarette social norms have focused on either injunctive or descriptive norms. Injunctive norms capture people’s beliefs about what others think ought to be done (e.g., social acceptability), whereas descriptive norms are perceptions of actual behavior within a social group (e.g., behaviors of friends and family) (Lapinski & Rimal, 2005). Social norm theory posits that injunctive and descriptive norms influence behavior in different ways. In particular, injunctive norms should mediate the effects of descriptive norms on behavior (Lapinski & Rimal, 2005), although this has not been tested in prior research on e-cigarettes. Furthermore, no studies of which we are aware have examined whether the influence of social norms is specific to particular tobacco products or generalizes across products.

A number of cross-sectional studies suggest that more favorable social norms, whether injunctive or descriptive, are associated with both e-cigarette and cigarette use. For example, a US study among university students found that current tobacco users (combining those who used cigarettes, e-cigarettes or hookahs in the last 30 days), reported greater social acceptability for e-cigarettes compared to students who did not use any tobacco products (Noland et al., 2016). US high school students who reported that either their friends had a favorable perception of e-cigarettes or who reported having at least one friend who used e-cigarettes were more likely to be susceptible to smoking, but susceptibility to e-cigarettes was not evaluated (Barrington-Trimis et al., 2016). US high school students who reported more family and friend use of e-cigarettes were also more likely to have ever used e-cigarettes or smoked (Gorukanti et al., 2017), and having a higher percentage of friends who use e-cigarettes was associated with greater frequency of e-cigarette use and dependence (Vogel, Ramo, & Rubinstein, 2018). Finally, studies of adolescents in Mexico (Thrasher et al., 2016) and Argentina (Morello et al., 2016) found that family and friend use of cigarettes was positively associated with e-cigarette trial, although network member use of e-cigarettes was not assessed. Results from these cross-sectional studies do not adequately account for potential selection effects (i.e., e-cigarette users are more likely become friends with people who use e-cigarettes). Furthermore, while the results generally indicate that norms around one product influence behavior associated with another product, they do not measure or assess the independent effects of each norm. Indeed, previous studies suggest that e-cigarettes may appeal to lower risk youth who would not have otherwise initiated nicotine product use (Thrasher et al., 2016; Wills, Sargent, Gibbons, Pagano, & Schweitzer, 2016). Hence, assessment of social norms that are specific to each product may be important to consider if e-cigarettes appeal to lower risk adolescents.

Evaluating the potential independence of e-cigarette and cigarette norms is also relevant to concerns that some have raised regarding how the increasing social acceptability of e-cigarettes may not only influence e-cigarette use but also smoking, thereby undermining “denormalization” policies and campaigns that have long targeted smoking (Abrams, 2014; Fairchild, Bayer, & Colgrove, 2014). Decades of public health campaigns and policy interventions, including smoke-free laws, advertising bans, and health warning labels on cigarette packaging (Fairchild et al., 2014; Gostin & Glasner, 2014), have made smoking less socially acceptable. These public health efforts could be reversed by the increasing popularity and favorable social norms towards e-cigarettes (Fairchild et al., 2014) if these norms increase use of both e-cigarettes and cigarettes (Barrington-Trimis et al., 2016). Indeed, this possibility is supported by longitudinal studies of adolescents and young adults in the US (Leventhal et al., 2015; Primack, Soneji, Stoolmiller, Fine, & Sargent, 2015; Soneji et al., 2017; Unger, Soto, & Leventhal, 2016; Wills, Knight, et al., 2016; Wills, Sargent, et al., 2016) and Mexico (Lozano et al., 2017), which have consistently found that e-cigarette trial and use are associated with subsequent cigarette smoking.

Mexican Study Context

Despite prohibiting the sale, importation, distribution, and marketing of e-cigarettes in Mexico (Artículo 16, 2008), a 2015 representative survey of first year middle-school students in the three largest cities in Mexico found that 10% had tried e-cigarettes. Furthermore, a 2016 nationally representative survey found that 7% of adolescents (12–17 years) had tried e-cigarettes and 1% were current users (Zavala-Arciniega et al., 2018). It is noteworthy that the prevalence of e-cigarette trial and use among Mexican adolescents is comparable to the prevalence of trial (11.9%) and use (3.5%) of e-cigarettes among US adolescents (12–17 years), where e-cigarette policies are relatively weak (Nicole, Snell, Morgan, & Andrew, 2017). It is unknown whether the relationships between social norms, risk perceptions, and use of e-cigarettes among adolescents varies across regulatory and sociocultural environments. Although in this study we did not directly compare data from countries with different e-cigarette regulations, we interpret the results in light of prior research that has almost exclusively been conducted in countries that have weaker regulations than Mexico

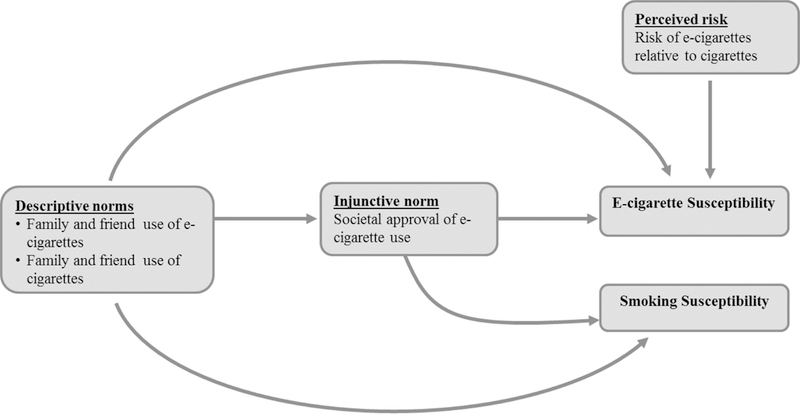

This paper is part of a larger study that has examined e-cigarette use among youth. Prior cross-sectional analyses of data from the first survey from this study suggest that awareness and trial of e-cigarette was high among first year secondary school adolescents in Mexico in spite of its e-cigarette ban (Thrasher et al., 2016). Moreover, we found that e-cigarette trial at baseline was associated with subsequent smoking initiation 20 months later (Lozano et al., 2017). At follow up, we asked more detailed questions about e-cigarette perceptions and use. The current study examines these more detailed questions amongst those who had not yet tried e-cigarettes in the follow-up survey. This study examined whether social norms (descriptive and injunctive) and risk perceptions that are specific to tobacco products are independently associated with e-cigarette and smoking susceptibility (i.e., openness to using the product in the next 12 months) (Figure 1). We focus on e-cigarette and smoking susceptibility among never users to help overcome concerns about selection effects that may have biased prior studies on the associations between norms and e-cigarette use. Based on norms theory (Lapinski & Rimal, 2005), we expect that perceived societal acceptability of e-cigarettes will mediate the effects of greater family and friend use of e-cigarettes on e-cigarette susceptibility. Based on prior research, we expect that family and friend use of e-cigarettes, as well as the social acceptability of e-cigarettes, will be independently associated with susceptibility to both smoking and e-cigarettes. Finally, we expect that perceived risk of e-cigarettes relative to cigarettes will be associated with e-cigarette susceptibility.

Figure 1.

A conceptual model of the relationship between social norms and perceived risk and e-cigarette and cigarette use

METHODS

Study Population

The data from this study were drawn from a school-based, representative survey of public middle-school students from the three largest cities in Mexico (Mexico City, Guadalajara, and Monterrey). Schools were selected using a stratified-random sampling scheme that considered: 1) high and low socioeconomic status, based on the census tracts were schools were located; and 2) city-specific tertiles of retail establishment density, which were estimated using an official database of commercial establishments likely to sell tobacco within school census tracts. A detailed description of school selection has been published elsewhere (Abad-Vivero et al., 2016).

The survey was conducted in October and November 2016 in 57 of the 60 schools that participated in a similar survey 18 months earlier. In both surveys, passive parental consent was used, with students providing active assent. Students completed a self-administered, Spanish-language questionnaire developed from prior, validated surveys and pretested to ensure student comprehension. Study protocols were approved by the IRB at the National Institute of Public Health in Mexico. Because questions on descriptive and injunctive social norms around e-cigarettes were not included in the 2015 survey, this study uses data only from the 2016 survey that included these questions.

Sample

Of 8718 students who participated in the survey, only 4,691 had never tried either e-cigarettes or cigarettes. Moreover, we excluded students with missing values from the dependent variables (current e-cigarette/cigarette susceptibility, N=12), primary independent variables (descriptive/ injunctive e-cigarette/ cigarette social norms and perceived risk, N=96) and all covariates (N=124), to yield a final analytic sample of 4,471 students.

Measures

Questions on smoking and e-cigarettes were in separate questionnaire sections. The section on e-cigarettes began with a brief description of e-cigarettes accompanied by images of different e-cigarette types.

Descriptive Norms:

To assess descriptive norms in the family, students were asked if any family members who lived at home used e-cigarettes (yes/no) or cigarettes (yes/no). Friend descriptive norms were measured by asking how many of their five best friends used e-cigarettes (none, 1 of 5, 2 of 5, 3 of 5, 4 of 5, 5 of 5), with a separate parallel question on friend use of cigarettes (Berg et al., 2015; Morello et al., 2016; Vogel et al., 2018). Response options were dichotomized to indicate that at least one of their friends used e-cigarette/ cigarettes vs. “none” of them. Responses to questions about both products were combined for product use among family (i.e., no family member who uses; only users of e-cigarettes; only cigarette smokers; users of both products) and friends (i.e., no friends who use; only users of e-cigarettes; only cigarette smokers; users of both products).

Injunctive norms:

Injunctive norms were assessed with a question on e-cigarette societal acceptability: “In your opinion, do people approve or disapprove that other people use e-cigarettes?” Response options to this question included: “they completely disapprove”, “they disapprove”, “they do not approve or disapprove”, “they approve” and “they completely approve”. We dichotomized responses into “yes” (they approve/they completely approve) and “no” (other responses).

Risk of e-cigarettes compared to cigarettes:

Students were asked how likely it would be for them to get a serious disease from using e-cigarettes if they used them for the rest of their lives. This question was also asked for cigarettes. Response options included: “it will not happen”, “not likely”, “likely”, “very likely”, “it will definitely happen”, “don’t know”. To examine the relative risk of e-cigarettes compared to cigarettes, responses were subtracted and categorized to yield the following response options: 1= “e-cigarettes are more risky/same”, 2= “e-cigarettes are less risky” and 3= “don’t know” (this category was determined before subtracting).

E-cigarette and smoking susceptibility:

As in prior research, susceptibility to each product was assessed by asking students using a validated question: Do you think that you will [use e-cigarettes/smoke] sometime in the next 12 months? (Bold, Kong, Cavallo, Camenga, & Krishnan-Sarin, 2016; Krishnan-Sarin, Morean, Camenga, Cavallo, & Kong, 2014; Pierce, Choi, Gilpin, Farkas, & Merritt, 1996). Response options for this question included: “Definitely not”, “not likely”, “likely”, and “definitely”. As is commonly done in tobacco research, we dichotomized responses into not susceptible (“definitely not” response) and susceptible (all other responses) (Morello et al., 2018; Pierce et al., 1996).

Covariates:

Sociodemographic characteristics included sex, age, parental education (highest level reported for either parent: primary, secondary, high school, university, unknown), and household wealth using the Family Affluence Scale (FAS) (i.e.; “How many cars does your family own?”; “Do you have your own room?”; “In the last 12 months how many times has your family gone on vacation?”; “How many computers are in your house?”) (Boyce, Torsheim, Currie, & Zambon, 2006). Personal characteristics included: a four-item scale of sensation seeking (e.g., “I like to do frightening things”; alpha=.80), which has been validated previously for Mexican youth (Thrasher et al., 2016) and a four-level alcohol use variable: never tried; tried, but not in the last 30 days; current drinking in the last 30 days (but not binge drinking); and binge drinking (4 drinks or more within 2 hours) in the last 30 days. Frequency of exposure to internet advertisements in the last 30 days for: 1. any tobacco product and; 2. e-cigarette products was queried (Morello et al., 2016; Thrasher et al., 2016), with responses re-categorized due to their skewed distribution (Never=“I don’t use the internet” or “never”, Sometimes=“rarely” or “sometimes”; Frequently= “frequently” or “very frequently”).

Statistical analysis

We calculated descriptive statistics for all variables of interest. We used generalized estimating equations (GEE) with log-binomial models to account for the school-level nested structure of the data (Fleischer et al., 2014). Unadjusted and adjusted GEE models were used to regress perceived e-cigarette injunctive norms (i.e., societal acceptability) on descriptive social norms (family and friend use) for both e-cigarettes and cigarettes and other covariates. GEE models also regressed e-cigarette/smoking susceptibility on e-cigarette social norms (i.e., descriptive and injunctive), cigarette social norms (i.e., descriptive), perceived risk, and covariates. If a significant association was found between e-cigarette and cigarette descriptive norms and e-cigarette injunctive norms, we also planned to test whether societal acceptability for e-cigarettes mediated the effects of family and friend use of e-cigarette on e-cigarette susceptibility. All analysis where conducted using STATA 14.

RESULTS

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the analytic sample (N=4,471) and participants excluded due to missing data (N=220). Students in the analytic sample were equally likely to be male or female, with most being 14 years old (78%) and having parents with a high school education or less (75%). The prevalence for both e-cigarette and smoking susceptibility was 22%. The prevalence of family and friend use of e-cigarettes was lower than for cigarettes. Approximately 8% of students perceived e-cigarette societal norms as favorable and 38% of students believed e-cigarettes were less risky than cigarettes. In general, differences between the analytic sample and the excluded sample were not statistically significant, with the exception of sex, age and alcohol use.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics for adolescent middle school students in Mexico, 2016 (N=4,471)

| Variables | Study sample±

N=4,501 |

Excluded sample±

N=220 (%) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 47% | 56% | 0.006 |

| Female | 53% | 43% | |

| Age | |||

| 12 to 13 | 9% | 10% | 0.009 |

| 14 | 78% | 70% | |

| 15 or more | 13% | 20% | |

| Parental education | |||

| Primary | 13% | 15% | 0.957 |

| Secondary | 41% | 41% | |

| High school | 22% | 21% | |

| University | 19% | 18% | |

| Unknown | 5% | 5% | |

| FAS* (mean) | 3.97 | 4.19 | 0.64 |

| Sensation seeking (mean) | 3.68 | 3.87 | 0.777 |

| Alcohol use | |||

| Never used | 51% | 61% | 0.033 |

| Ever tried (not current) | 33% | 22% | |

| Current drinking (not binging) | 13% | 13% | |

| Current binge drinking | 3% | 4% | |

| Exposure to online e-cigarette ads | |||

| Never | 74% | 70% | 0.135 |

| Sometimes | 23% | 24% | |

| Always | 3% | 6% | |

| Exposure to online cigarette ads | |||

| Never | 83% | 87% | 0.159 |

| Sometimes | 14% | 11% | |

| Always | 3% | 2% | |

| Family use of nicotine products | |||

| Neither product | 43% | 44% | 0.235 |

| E-cigarette only | 2% | 3% | |

| Conventional cigarette only | 49% | 46% | |

| Both | 6% | 6% | |

| Friend use of nicotine products | |||

| Neither product | 54% | 65% | 0.059 |

| E-cigarette only | 6% | 8% | |

| Conventional cigarette only | 22% | 28% | |

| Both | 17% | 18% | |

| Societal acceptability of e-cigarettes | 0.513 | ||

| Yes | 8% | 10% | |

| E-cigarette risk compared to cigarettes | |||

| E-cigarettes are more risky/ same | 41% | 40% | 0.9791 |

| E-cigarettes are less risky | 38% | 39% | |

| Don’t know | 21% | 20% | |

| E-cigarette susceptibility | |||

| Yes | 22% | 15% | 0.431 |

| Smoking susceptibility | |||

| Yes | 22% | 19% | 0.203 |

FAS=Family affluence scale

In crude and adjusted GEE models, perceived social acceptability (Table 2) was associated with moderate exposure to online e-cigarette advertisements in the last month compared to students who reported no exposure (11% vs. 7%, respectively; APRsometimes v.s never 1.39, 95% CI 1.12–1.73). Because friend and family use of e-cigarettes and cigarettes were not independently associated with social acceptability of e-cigarettes, we did not test further for mediation effects on e-cigarette or smoking susceptibility.

Table 2.

Unadjusted and adjusted associations between societal acceptability of e-cigarettes and study variables among middle-school adolescents in Mexico, 2016 (N=4,471)

| Societal acceptability of e-cigarettes | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| % | PR 95% IC | APR 95% IC | |

| Family use of nicotine products | |||

| Neither product | 8 | 1 | 1 |

| E-cigarette only | 10 | 1.26 (0.54 – 2.95) | 1.10 (0.93 – 1.30) |

| Conventional cigarette only | 9 | 1.13 (0.95 – 1.34) | 1.23 (0.53 – 2.84) |

| Both | 11 | 1.41 (0.99 – 2.01) | 1.26 (0.86 – 1.84) |

| Friend use of nicotine products | |||

| Neither product | 8 | 1 | 1 |

| E-cigarette only | 11 | 1.37 (0.94 – 2.01) | 1.26 (0.87 – 1.83) |

| Conventional cigarette only | 7 | 0.90 (0.71 – 1.15) | 0.85 (0.67 – 1.07) |

| Both | 11 | 1.41 (1.13 – 1.75) | 1.21 (0.95 – 1.55) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 9 | 1 | 1 |

| Male | 9 | 0.92 (0.77 – 1.11) | 0.95 (0.78 – 1.15) |

| Age | |||

| 12 to 13 | 7 | 1 | 1 |

| 14 | 8 | 1.18 (0.87 – 1.61) | 1.19 (0.88 – 1.61) |

| 15 or more | 9 | 1.28 (0.82 – 1.99) | 1.27 (0.82 – 1.99) |

| Parental education | |||

| Primary | 7 | 1 | 1 |

| Secondary | 9 | 1.35 (0.95 – 1.92) | 1.35 (0.96 – 1.89) |

| High school | 8 | 1.22 (0.87 – 1.73) | 1.23 (0.87 – 1.73) |

| University | 9 | 1.24 (0.90 – 1.70) | 1.19 (0.86– 1.66) |

| Unknown | 7 | 1.01 (0.63 – 1.63) | 1.05 (0.65 – 1.70) |

| FAS* (mean) | 4.12 | 1.03 (0.99 – 1.08) | 1.02 (0.97 – 1.07) |

| Sensation seeking (mean) | 3.75 | 1.11 (1.00 – 1.22) | 1.04 (0.94 – 1.17) |

| Alcohol use | |||

| Never used | 8 | 1 | 1 |

| Ever tried (not current) | 8 | 1.01 (0.82 – 1.25) | 0.95 (0.76 – 1.18) |

| Current drinking (not binging) | 11 | 1.40 (1.02 – 1.93) | 1.26 (0.91 – 1.75) |

| Current binge drinking | 12 | 1.52 (0.88 – 2.61) | 1.29 (0.75 – 2.22) |

| Exposure to online e-cigarette ads | |||

| Never | 7 | 1 | 1 |

| Sometimes | 11 | 1.51 (1.24 – 1.83) | 1.39 (1.12 – 1.73) |

| Always | 12 | 1.66 (0.98 – 2.78) | 1.49 (0.86 – 2.58) |

FAS=Family affluence scale

In general, susceptibility to both e-cigarettes and smoking was higher among students who reported that their family and friends used either cigarettes only or both products compared to students whose family and friends did not use either of these products (Table 3). Students who reported that their friends only used e-cigarettes (but not cigarettes) were more likely to be susceptible to e-cigarettes than students with no friends who used either product (25% vs. 16%, respectively; APR=1.33, 95% CI 1.08–1.69). Having friends who only used e-cigarettes was not significantly associated with smoking susceptibility. Perceived social acceptability of e-cigarettes was independently associated with greater likelihood of e-cigarette susceptibility (APR=1.17, 95% CI 1.02–1.35) but not with smoking susceptibility. The belief that e-cigarettes are less risky than smoking (APR=1.45, 95% CI 1.29–1.64) was also associated with e-cigarette susceptibility, but not with smoking susceptibility. Common independent correlates for susceptibility to both smoking and e-cigarettes included stronger sensation seeking and binge drinking (compared to never drinkers). Independent associations that were unique to e-cigarette susceptibility included sex (APRmale vs female=0.87, 95% CI 0.79–0.96) and being exposed to online e-cigarette products ads (APRalways vs never=1.31, 95% CI 1.03–1.66). Furthermore, students with parents whose educational attainment was relatively high were less likely to be susceptible to cigarette use (APRuniversity vs. primary school=0.73, 95% CI 0.62–0.87).

Table 3.

Association between susceptibility to e-cigarettes, to cigarettes and study variables among Mexican middle school adolescents who have not used either product, 2016

| Variables | E-cigarette susceptibility (n=4,471) | Cigarette susceptibility (n=4,471) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | PR 95% IC | APRb 95% IC | % | PR 95% IC | APRb 95% IC | |

| Family use of nicotine products | ||||||

| Neither product | 17 | 1 | 1 | 17 | 1 | 1 |

| E-cigarette only | 14 | 0.85 (0.48 – 1.49) | 0.69 (0.41 – 1.19) | 20 | 1.18 (0.73 – 1.90) | 1.05 (0.66 – 1.68) |

| Conventional cigarette only | 25 | 1.45 (1.29 – 1.63) | 1.27 (1.14 – 1.43) | 27 | 1.54 (1.39 – 1.72) | 1.34 (1.20 – 1.49) |

| Both | 32 | 1.82 (1.52 – 2.18) | 1.38 (1.16 – 1.64) | 33 | 1.87 (1.56 – 2.25) | 1.50 (1.26 – 1.80) |

| Friend use of nicotine products | ||||||

| Neither product | 16 | 1 | 1 | 17 | 1 | 1 |

| E-cigarette only | 26 | 1.60 (1.29 – 1.99) | 1.33 (1.08 – 1.63) | 21 | 1.23 (0.98 – 1.55) | 1.05 (0.83 – 1.33) |

| Conventional cigarette only | 24 | 1.57 (1.34 – 1.83) | 1.30 (1.12 – 1.51) | 30 | 1.76 (1.54 – 2.00) | 1.46 (1.28 – 1.65) |

| Both | 38 | 2.45 (2.12 – 2.82) | 1.80 (1.57 – 2.07) | 34 | 2.00 (1.77 – 2.27) | 1.06 (1.38 – 1.77) |

| Societal acceptability of e-cigarettes | ||||||

| No | 21 | 1 | 1 | 23 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 28 | 1.32 (1.13 – 1.54) | 1.17 (1.02 – 1.35) | 26 | 1.13 (0.96 – 1.34) | 1.03 (0.86 – 1.24) |

| E-cigarette risk compared to cigarettes | ||||||

| E-cigarettes are more risky/ same | 18 | 1 | 1 | 21 | 1 | 1 |

| E-cigarettes are less risky | 29 | 1.56 (1.39 – 1.75) | 1.45 (1.29 – 1.64) | 28 | 1.33 (1.10 – 1.47) | 1.25 (0.94 – 1.37) |

| Don’t know | 18 | 0.97 (0.81 – 1.15) | 1.01 (0.84 – 1.20) | 18 | 0.88 (0.75 – 1.03) | 0.89 (0.76 – 1.04) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 24 | 1 | 1 | 24 | 1 | 1 |

| Male | 20 | 0.81 (0.74 – 0.89) | 0.87 (0.79 – 0.96) | 22 | 0.81 (0.74 – 0.89) | 0.99 (0.89 – 1.11) |

| Age | ||||||

| 12 to 13 | 23 | 1 | 1 | 22 | 1 | 1 |

| 14 | 22 | 0.98 (0.81 – 1.17) | 0.94 (0.79 – 1.12) | 23 | 1.04 (0.87 – 1.23) | 1.02 (0.87 – 1.20) |

| 15 or more | 21 | 0.95 (0.73 – 1.23) | 0.90 (0.70 – 1.17) | 23 | 1.01 (0.79 – 1.30) | 0.95 (0.74 – 1.20) |

| Parental education | ||||||

| Primary | 23 | 1 | 1 | 28 | 1 | 1 |

| Secondary | 22 | 0.91 (0.80 – 1.05) | 0.92 (0.81 – 1.04) | 24 | 0.85 (0.73 – 0.99) | 0.88 (0.75 – 1.03) |

| High school | 24 | 1.02 (0.86 – 1.21) | 1.08 (0.89 – 1.30) | 22 | 0.81 (0.69 – 0.95) | 0.87 (0.74 – 1.03) |

| University | 21 | 0.85 (0.72 – 1.02) | 0.89 (0.75 – 1.05) | 19 | 0.69 (0.58 – 0.82) | 0.73 (0.62 – 0.87) |

| Unknown | 18 | 0.75 (0.57 – 1.00) | 0.93 (0.72 – 1.20) | 20 | 0.73 (0.55 – 0.98) | 0.90 (0.68 – 1.18) |

| FAS± (mean) | 4.06 | 1.02 (0.99 – 1.05) | 1.00 (0.97 – 1.03) | 4.02 | 1.01 (0.98 – 1.04) | 1.01 (0.98 – 1.04) |

| Sensation seeking (mean) | 3.92 | 1.39 (1.31 – 1.48) | 1.22 (1.15 – 1.30) | 3.91 | 1.38 (1.28 – 1.49) | 1.23 (1.14 – 1.34) |

| Alcohol use | ||||||

| Never used | 14 | 1 | 1 | 15 | 1 | 1 |

| Ever tried (not current) | 29 | 2.00 (1.72 – 2.32) | 1.62 (1.41 – 1.86) | 28 | 1.81 (1.62 – 2.03)) | 1.53 (1.37 – 1.71) |

| Current drinking (not binging) | 32 | 2.28 (1.94 – 2.67) | 1.68 (1.42 – 1.98) | 36 | 2.36 (2.08 – 2.68) | 1.83 (1.60 – 2.09) |

| Current binge drinking | 39 | 2.73 (2.21 – 3.37) | 1.70 (1.34 – 2.14) | 52 | 3.42 (2.83 – 4.13) | 2.35 (1.89 – 2.92) |

| Exposure to online e-cigarette ads | ||||||

| Never | 20 | 1 | 1 | 20 | ||

| Sometimes | 30 | 1.86 (1.66 – 2.09) | 1.51 (1.34 – 1.71) | 31 | ||

| Always | 26 | 1.78 (1.39 – 2.28) | 1.31 (1.03 – 1.66) | 34 | ||

| Exposure to online tobacco ads | ||||||

| Never | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Sometimes | 1.33 (1.16– 1.52) | 1.10 (0.97 – 1.26) | ||||

| Always | 1.12 (0.79– 1.57) | 0.80 (0.57 – 1.13) | ||||

Analytical Sample: Adolescents who had not tried e-cigarettes or cigarettes

FAS=Family affluence scale

DISCUSSION

Results from this study did not support our primary hypotheses, based in social norm theory (Lapinski & Rimal, 2005), around how family and/or friend use of e-cigarettes would influence social acceptability of e-cigarettes. In other words, students who reported that their friends and family used cigarettes and/or e-cigarettes, were no more likely to perceive e-cigarettes as socially acceptable than students that reported that their friends and family did not use either nicotine product. However, this lack of association may be due to how we measured social acceptability, which only referenced perceived opinions of other people in general. Future research should consider assessing social acceptability among more proximal social network members that are likely to influence behavior, such as friends and family. Indeed, a previous study that examined the correlates of e-cigarette social acceptability among family and friends found that being male, a current tobacco user (user of cigarettes, e-cigarettes or hookah) and being exposed to second hand cigarette smoking was associated with perceived social acceptability of e-cigarettes (Noland et al., 2016). However, this study did not examine family or friend use of e-cigarette as a correlate of social acceptability

Our study found that perceived social acceptability of e-cigarettes was independently associated with e-cigarette susceptibility but not with smoking susceptibility. Hence, e-cigarette social acceptability may have a specific effect on e-cigarette susceptibility without influencing smoking behavior. This contrasts with a cross-sectional US study that found that perceived favorability of e-cigarettes among friends was associated with smoking susceptibility (Barrington-Trimis et al., 2016). However, this study did not examine the relationship between social acceptability of e-cigarettes and e-cigarette susceptibility. It is possible that this relationship will be stronger in the US where e-cigarettes are not banned and therefore may be more easily accessible to youth.

Students who had family or friends who used both e-cigarettes and cigarettes or used just cigarettes were more likely to be susceptible to either product, when compared to students whose family or friends used neither product. This is consistent with other research among US adolescents, which found that secondhand cigarette smoke exposure in the home was a risk factor for e-cigarette susceptibility (Kwon, Seo, Lin, & Chen, 2018). Furthermore, receiving their first e-cigarette from a family member was associated with more frequent use of e-cigarettes among US adolescents who use them (Vogel et al., 2018). Nevertheless, we also found that having friends who only use e-cigarettes was associated with e-cigarette susceptibility, but not with smoking susceptibility and family e-cigarette use was not independently associated with susceptibility to either product. This raises the question of whether e-cigarette use among close network members will ultimately lead to cigarette use – a question that future longitudinal research should assess. In the end, e-cigarette use among friends may play a more important role in adolescent e-cigarette uptake compared to family e-cigarette use (Gorukanti et al., 2017).

Students who perceive e-cigarettes use to be less risky than smoking were more likely to be susceptible to e-cigarettes, as in prior research (Kwon et al., 2018). Thus, policies and public health programs that aim to inform youth about the dangers and harmfulness of e-cigarettes may be important for deterring e-cigarette initiation and use.

We found that exposure to online e-cigarette ads in the last 30 days was independently associated both with perceived social acceptability of e-cigarettes and with e-cigarette susceptibility. This finding is consistent with a cross-sectional study among undergraduate students that suggest that favorable injunctive norms around online video advertisement was positively associated to consumers’ intention to watch online video ads on social media (Lee, Kim, Ham, & Kim, 2017). E-cigarette information is widely available online (Collins, Glasser, Abudayyeh, Pearson, & Villanti, 2018) and research indicates that e-cigarette advertisement may play a role in making this products more socially acceptable (Willis, Haught, & Morris Ii, 2017).. Difficulties with enforcing online ad restriction may lead to significant exposures even in countries where e-cigarettes are banned, such as Mexico and many other countries that have banned e-cigarette advertising (Institute for Global Tobacco Control, 2018). As such, online marketing may play an important role in forming perceptions about the social acceptability of e-cigarettes and in promoting their use among adolescents.

As expected, we found that sensation seeking and alcohol use were associated with susceptibility to e-cigarettes and cigarettes, both of which are establish risk factors for youth smoking (Tyas & Pederson, 1998) and e-cigarette susceptibility and trial (Kwon et al., 2018; Thrasher et al., 2016). Indeed, sensation seeking is a robust predictor of a variety of substance use and risk behaviors among adolescents. Because these youth also appear more likely to be open to e-cigarette use (Hughes et al., 2015), it may be possible to target prevention campaigns to youth in this group, as has been done for smoking and other substance use behaviors (D’Silva, Harrington, Palmgreen, Donohew, & Lorch, 2001; Sargent, Tanski, Stoolmiller, & Hanewinkel, 2010)

Our study has some limitations. First, due to the cross-sectional nature of the data we cannot draw causal conclusions about the relationships between the primary study variables. Basing our study in a clear conceptual model helps address this concern to some extent, but future studies should examine these relationships longitudinally. However, in the absence of longitudinal data, susceptibility to future e-cigarette use helps to address concerns about the temporal relationship between behavior and psychosocial outcomes, and susceptibility is a reasonable proxy for future behavior, including for both e-cigarette initiation (Bold et al., 2016) and cigarette initiation (Morello et al., 2018; Pierce et al., 1996). Measurement of norms was somewhat limited, especially for social acceptability, and future research should consider assessing social acceptability among specific groups that are likely to influence behavior, such as friends and family. Moreover, the timeframe for reported e-cigarette use among family and friends was not specified, although this practice is standard and recommended in tobacco research (PhenX Toolkit, 2018; Press, 2013). Similarly, the e-cigarette susceptibility questions were pretested but not specifically validated – although their structure and content is based on standard, recommended questions for cigarettes and shown to have predictive validity among US youth (Bold et al., 2016). Future studies should validate these questions among youth across different sociocultural contexts. Although our sample was large and representative of public schools in the three largest cities in Mexico, results may not generalize to other populations in Mexico. However, more than 75% of Mexicans live in urban areas, and we expect the results are broadly representative. Finally, this study may have been susceptible to selection bias as 220 participants were excluded due to missing data. However, differences in the distribution of the variables in the study sample and the excluded sample were not statistically significant, with the exception of sex, age and alcohol use, for which we controlled in our analyses.

In conclusion, findings from this research are generally consistent with the body of research around the importance of social norms for promoting tobacco product use; although we provide some additional evidence that their effects are somewhat specific to the type of tobacco product used. Results around the association between risk perceptions and susceptibility to e-cigarette use suggest that communication campaigns about e-cigarettes may be necessary to inform youth about the dangers of use to deter youth e-cigarette uptake.

Acknowledgments

Source of funding

This research was supported by a grant from the Fogarty International Center and the National Cancer Institute of the United States’ National Institute of Health (R01 TW009274 & R01 TW010652). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

No conflict declared.

References

- Abad-Vivero EN, Thrasher JF, Arillo-Santillán E, Pérez-Hernández R, Barrientos-Gutíerrez I, Kollath-Cattano C, … Sargent JD (2016). Recall, appeal and willingness to try cigarettes with flavour capsules: assessing the impact of a tobacco product innovation among early adolescents. Tobacco Control, tobaccocontrol-2015–052805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Abrams DB (2014). Promise and peril of e-cigarettes: can disruptive technology make cigarettes obsolete? Jama, 311(2), 135–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artículo 16, a. V. L. g. d. s. (2008). Ley General para el Control del Tabaco. México, 2007. salud pública de méxico, 50(suplemento 3). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrington-Trimis JL, Berhane K, Unger JB, Cruz TB, Urman R, Chou CP, … Gilreath TD (2016). The e-cigarette social environment, e-cigarette use, and susceptibility to cigarette smoking. Journal of Adolescent Health, 59(1), 75–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg CJ, Stratton E, Schauer GL, Lewis M, Wang Y, Windle M, & Kegler M (2015). Perceived harm, addictiveness, and social acceptability of tobacco products and marijuana among young adults: marijuana, hookah, and electronic cigarettes win. Substance use & misuse, 50(1), 79–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatnagar A, Whitsel L, & Ribisl K (2014). Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, and Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research. Electronic cigarettes: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 130(16), 1418–1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bold KW, Kong G, Cavallo DA, Camenga DR, & Krishnan-Sarin S (2016). E-cigarette susceptibility as a predictor of youth initiation of e-cigarettes. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, ntw393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Boyce W, Torsheim T, Currie C, & Zambon A (2006). The family affluence scale as a measure of national wealth: validation of an adolescent self-report measure. Social indicators research, 78(3), 473–487. [Google Scholar]

- Choi K, & Forster J (2013). Characteristics associated with awareness, perceptions, and use of electronic nicotine delivery systems among young US Midwestern adults. American journal of public health, 103(3), 556–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins L, Glasser AM, Abudayyeh H, Pearson JL, & Villanti AC (2018). E-Cigarette Marketing and Communication: How E-Cigarette Companies Market E-Cigarettes and the Public Engages with E-cigarette Information. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 1, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Silva MU, Harrington NG, Palmgreen P, Donohew L, & Lorch EP (2001). Drug use prevention for the high sensation seeker: The role of alternative activities. Substance Use and Misuse, 36(3), 373–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairchild AL, Bayer R, & Colgrove J (2014). The renormalization of smoking? E-cigarettes and the tobacco “endgame”. New England Journal of Medicine, 370(4), 293–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischer NL, Thrasher JF, de Miera Juárez BS, Reynales-Shigematsu LM, Santillán EA, Osman A, … Fong GT (2014). Neighbourhood deprivation and smoking and quit behaviour among smokers in Mexico: findings from the ITC Mexico Survey. Tobacco Control, tobaccocontrol-2013–051495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Goniewicz ML, Lingas EO, & Hajek P (2013). Patterns of electronic cigarette use and user beliefs about their safety and benefits: an internet survey. Drug and alcohol review, 32(2), 133–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorukanti A, Delucchi K, Ling P, Fisher-Travis R, & Halpern-Felsher B (2017). Adolescents’ attitudes towards e-cigarette ingredients, safety, addictive properties, social norms, and regulation. Preventive medicine, 94, 65–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gostin LO, & Glasner AY (2014). E-cigarettes, vaping, and youth. Jama, 312(6), 595–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grana RA (2013). Electronic cigarettes: a new nicotine gateway? Journal of Adolescent Health, 52(2), 135–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes K, Bellis MA, Hardcastle KA, McHale P, Bennett A, Ireland R, & Pike K (2015). Associations between e-cigarette access and smoking and drinking behaviours in teenagers. BMC Public Health, 15(1), 244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Global Tobacco Control. (2018). Country Laws Regulating E-cigarettes: A Policy Scan Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health; Retrieved from http://globaltobaccocontrol.org/e-cigarette/country-laws-regulating-e-cigarettes [March 19, 2018] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan-Sarin S, Morean ME, Camenga DR, Cavallo DA, & Kong G (2014). E-cigarette use among high school and middle school adolescents in Connecticut. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 17(7), 810–818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon E, Seo D-C, Lin H-C, & Chen Z (2018). Predictors of youth e-cigarette use susceptibility in a US nationally representative sample. Addictive Behaviors, 82, 79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapinski MK, & Rimal RN (2005). An explication of social norms. Communication theory, 15(2), 127–147. [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Kim M, Ham C-D, & Kim S (2017). Do you want me to watch this ad on social media?: The effects of norms on online video ad watching. Journal of Marketing Communications, 23(5), 456–472. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal AM, Strong DR, Kirkpatrick MG, Unger JB, Sussman S, Riggs NR, … Audrain-McGovern J (2015). Association of Electronic Cigarette Use With Initiation of Combustible Tobacco Product Smoking in Early Adolescence. Jama, 314(7), 700–707. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.8950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozano P, Barrientos-Gutierrez I, Arillo-Santillan E, Morello P, Mejia R, Sargent JD, & Thrasher JF (2017). A longitudinal study of electronic cigarette use and onset of conventional cigarette smoking and marijuana use among Mexican adolescents. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 180, 427–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis KA, Nguyen AB, Slavit WI, & King BA (2016). E-cigarette curiosity among US middle and high school students: findings from the 2014 National Youth Tobacco Survey. Preventive medicine, 89, 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morello P, Pérez A, Braun SN, Thrasher JF, Barrientos I, Arillo-Santillán E, & Mejía R (2018). Smoking susceptibility as a predictive measure of cigarette and e-cigarette use among early adolescents. Salud Publica de México, 60(4, jul-ago), 423–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morello P, Perez A, Peña L, Lozano P, Thrasher JF, Sargent J, & Mejia R (2016). Prevalence and predictors of e-cigarette trial among adolescents in Argentina. Tobacco Prevention & Cessation, 2(December). doi: 10.18332/tpc/66950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicole E, Snell M, Morgan L, & Andrew J (2017). Does Exposure and Receptivity to E-cigarette Advertisements Relate to E-cigarette and Conventional Cigarette Use Behaviors among Youth? Results from Wave 1 of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study. Journal of Applied Research on Children: Informing Policy for Children at Risk, 8(2), 3. [Google Scholar]

- Noel JK, Rees VW, & Connolly GN (2011). Electronic cigarettes: a new ‘tobacco’industry? Tobacco Control, 20(1), 81–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noland M, Ickes MJ, Rayens MK, Butler K, Wiggins AT, & Hahn EJ (2016). Social influences on use of cigarettes, e-cigarettes, and hookah by college students. Journal of American College Health, 64(4), 319–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PhenX Toolkit. (2018, August 1, 2018). Protocol - Social Norms about Tobacco - Youth Retrieved from http://www.phenxtoolkit.org/protocols/view/750302

- Pierce JP, Choi WS, Gilpin EA, Farkas AJ, & Merritt RK (1996). Validation of susceptibility as a predictor of which adolescents take up smoking in the United States. Health Psychology, 15(5), 355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Press R. (2013). PhenX—Establishing a consensus process to select common measures for collaborative research [PubMed]

- Primack BA, Soneji S, Stoolmiller M, Fine MJ, & Sargent JD (2015). Progression to traditional cigarette smoking after electronic cigarette use among US adolescents and young adults. JAMA pediatrics, 169(11), 1018–1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roditis M, Delucchi K, Cash D, & Halpern-Felsher B (2016). Adolescents’ perceptions of health risks, social risks, and benefits differ across tobacco products. Journal of Adolescent Health, 58(5), 558–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent JD, Tanski S, Stoolmiller M, & Hanewinkel R (2010). Using sensation seeking to target adolescents for substance use interventions. Addiction, 105(3), 506–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soneji S, Barrington-Trimis JL, Wills TA, Leventhal AM, Unger JB, Gibson LA, … Miech RA (2017). Association between initial use of e-cigarettes and subsequent cigarette smoking among adolescents and young adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA pediatrics, 171(8), 788–797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrasher JF, Abad-Vivero EN, Barrientos-Gutíerrez I, Pérez-Hernández R, Reynales-Shigematsu LM, Mejía R, … Sargent JD (2016). Prevalence and correlates of e-cigarette perceptions and trial among early adolescents in Mexico. Journal of Adolescent Health, 58(3), 358–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trumbo CW, & Harper R (2015). Orientation of US Young Adults toward E-cigarettes and their Use in Public. Health behavior and policy review, 2(2), 163–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyas SL, & Pederson LL (1998). Psychosocial factors related to adolescent smoking: a critical review of the literature. Tobacco Control, 7(4), 409–420. doi: 10.1136/tc.7.4.409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger JB, Soto DW, & Leventhal A (2016). E-cigarette use and subsequent cigarette and marijuana use among Hispanic young adults. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 163, 261–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel EA, Ramo DE, & Rubinstein ML (2018). Prevalence and correlates of adolescents’e-cigarette use frequency and dependence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Willis E, Haught MJ, & Morris Ii DL (2017). Up in Vapor: Exploring the Health Messages of E-Cigarette Advertisements. Health Communication, 32(3), 372–380. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2016.1138388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Knight R, Sargent JD, Gibbons FX, Pagano I, & Williams RJ (2016). Longitudinal study of e-cigarette use and onset of cigarette smoking among high school students in Hawaii. Tobacco Control, tobaccocontrol-2015–052705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wills TA, Sargent JD, Gibbons FX, Pagano I, & Schweitzer R (2016). E-cigarette use is differentially related to smoking onset among lower risk adolescents. Tobacco control, tobaccocontrol-2016–053116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zavala-Arciniega L, Rodríguez-Andrade MÁ, Reynales-Shigematsu LM, Lozano P, Arillo Santillán E, & Thrasher JF (2018). Patterns of awareness and use of electronic cigarettes in Mexico, a middle-income country that bans them: Results from a 2016 national survey. Preventive Medicine (Baltimore), (under review). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]