Abstract

Background:

Youth from continuation high schools report greater substance use and sensation-seeking than youth from regular high schools, yet their long-term consequences on age at sexual onset and the number of sexual partners are unknown.

Objective:

To examine substance use, sensation-seeking and sexual behaviors by gender and race/ethnicity and the effects of substance use and sensation-seeking in adolescence on age at sexual initiation and numbers of sexual partners by young adulthood.

Methods:

Baseline and 4-year follow-up data on youth from 14 continuation high schools in Southern California who participated in a drug abuse prevention intervention were analyzed. Structural equation modeling assessed whether or not substance use or sensation-seeking in adolescence predicted age at sexual onset and numbers of sexual partners by young adulthood.

Results:

Latinos had lower sensation-seeking and frequency of substance use and a later age at sexual onset than non-Latinos. Males were more likely than females to have multiple lifetime and recent sexual partners. The effects of adolescent substance use on the number of sexual partners by young adulthood were mediated fully by their age at sexual initiation. Sensation-seeking had no direct or indirect effects on sexual behaviors.

Conclusions/Importance:

Factors leading to and actual sexual risk behaviors among youth from continuation high schools vary by race/ethnicity and gender. Targeting these antecedent factors by race/ethnicity and gender may improve prevention efforts.

Keywords: adolescents, continuation high schools, sensation-seeking, sexual behaviors, sexual onset, substance use

Introduction

High school adolescents, ages 13–18 years, are reporting a later age at sexual onset and fewer sexual partners (CDC, 2015), but it is unknown if these trends also hold for youth in continuation high schools. About 2% of students attend alternative or continuation high schools (CHS) when they are considered at risk of withdrawing from high school for various reasons (e.g., truancy, disciplinary problems; National Center for Education Statistics, 2012). CHS youth are at particular risk for deleterious health outcomes given their propensity to attend classes irregularly and subsequent availability for involvement in risk behaviors.

Although CHS provide a structured environment and specialized skills, CHS youth are exposed to an environment where substance use and sexual risk-taking behaviors are higher than in regular high schools (CDC, 1999; CDC, 2000; Sussman et al., 1995). Compared to the national 1999 Youth Risk Behavior Survey sample, CHS youth in the Alternative High School Youth Risk Behavior Survey (ALT-YRBS) sample in 1998 were at least twice as likely to have smoked cigarettes, drank alcohol and used marijuana and at least three times more likely to have engaged in sexual intercourse, had multiple sexual partners, initiated sexual intercourse by age 13 years, and used substances prior to last sexual intercourse (CDC, 1999; CDC, 2000; Grunbaum, Lowry, & Kann, 2001; Grunbaum, Tortolero, Weller, & Gingiss, 2000). Among CHS youth who participated in sexual risk-reduction interventions, at least two-thirds had had sex and were currently sexually active (Coyle et al., 2006; Coyle et al., 2013; Tortolero et al., 2008). About 42% had initiated sex by 13 years of age, and one-third used substances prior to sex (Tortolero et al., 2008). While trend data are available for high school youth and show decreased sexual risk-taking, national trend and current data are unavailable for CHS youth since ALT-YRBS was only conducted in 1998, making these aged data.

Longitudinal studies conducted with CHS youth are limited and address either substance use (Kwan, Sussman & Valente, 2015; Myers et al., 2009; Pokhrel, Sussman & Stacy, 2014) or sexual behaviors (Coyle et al., 2006; Coyle et al., 2013; Tortolero et al., 2008) as outcomes and have not explored the path between these two behaviors. Additionally sensation-seeking, a personality trait with a tendency to seek varied and exciting experiences, has been explored with substance use (Pokhrel, Sussman & Stacy, 2014) but not sexual behaviors among CHS youth. The effects of adolescent substance use and sensation-seeking on age at sexual onset and numbers of sexual partners by young adulthood among former CHS youth with heightened risk behaviors remain unclear. Understanding the long-term impact of substance use and sensation-seeking on these sexual behaviors among adolescents who engage in risk behaviors and are exposed to a social environment that condones these behaviors may inform targeted health promotion interventions. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to assess if substance use and sensation-seeking during adolescence was predictive of age at sexual onset and the numbers of sexual partners by young adulthood among former CHS youth.

Substance use and sexual behaviors

Substance use like alcohol, marijuana and/or cigarettes often co-occurs with risky sexual behaviors (i.e., earlier age at sexual onset, multiple sexual partners). Youth who initiate sex by 15 years of age often report multiple sexual partners (Epstein et al., 2014; Kaplan, Jones, Olson, & Yunzal-Butler, 2013; Lowry, Dunville, Robin, & Kann, 2017; Lowry, Robin, & Kann, 2017; Magnusson, Nield, & Lapane, 2015). Alcohol and marijuana use can produce behavioral disinhibition whereby one’s decision-making abilities to delay sexual initiation or reduce the number of sexual partners are compromised. Early substance use precedes or is associated with sexual initiation in adolescent males (Capaldi, Kerr, Owen, & Tiberio, 2017; Doran & Waldron, 2017; Epstein et al., 2014; Floyd & Latimer, 2010) and females (Cavazos-Rehg et al., 2012; Dillon et al., 2010; Doran & Waldron, 2017; Epstein et al., 2014; Floyd & Latimer, 2010) as well as African American (Kaplan et al., 2013; McGuire, Wang & Zhang, 2012; Turner, Latkin, Sonenstein, & Tandon, 2011) and Latino youth (Dillon et al., 2010; Kaplan et al., 2013). Numbers of sexual partners increases as alcohol (Epstein et al., 2014; Green et al., 2017; Oshri et al., 2014; Riggs et al., 2013; Vasilenko & Lanza, 2014), marijuana (Cavazos-Rehg et al., 2011; Floyd & Latimer, 2010; Green et al., 2017; Oshri et al., 2014) or smoking (Cavazos-Rehg et al., 2011; Demissie et al., 2017; McGuire, Wang & Zhang, 2012; Vasilenko & Lanza, 2014) use increases. However, alcohol use was not associated with number of sexual partners among a national representative sample of youth (Floyd & Latimer, 2010).

Although some studies have focused on substance use specifically in CHS youth (Kwan, Sussman & Valente, 2015; Myers et al., 2009; Pokhrel, Sussman & Stacy, 2014), three intervention studies since 2000 have targeted sexual risk-taking behaviors in CHS youth. Among ethnically diverse CHS youth in the Safer Choices 2 intervention in Texas, baseline prevalence of sexual behaviors, substance use, and engaging in multiple problematic behaviors were high (Tortolero et al., 2008). The number of sexual partners and the pathway between substance use and sexual risk-taking are unknown because longitudinal results are not readily available. Coyle et al. (2006) and Coyle et al. (2013) implemented a sexual risk-reduction intervention for CHS youth in California. Like Tortolero et al.’s (2008) findings, the majority of CHS youth in the All4You! interventions had engaged in sexual intercourse and were currently sexually active. Significant reductions in unprotected sexual intercourse by 6-month follow-up were observed, but these changes were short-term and not sustained. Furthermore, age at sexual onset, number of sexual partners (regardless of condom use) and the role of substance use on sexual behaviors were not factored into these studies.

Sensation-seeking and sexual behaviors

Sensation-seeking may also produce some disinhibition that impacts decision-making and sexual risk-taking. High sensation-seekers may be more likely to use substances and have multiple sexual partners to fulfill desires for exciting experiences. Traditionally explored with substance use, sensation-seeking is significantly associated with alcohol, cigarette and marijuana use in high school (Byck, Swann, Schalet, Bolland, & Mustanski, 2015; Kong et al., 2013; Voisin, King, Schneider, DiClemente, & Tan, 2012) and CHS youth (Pokhrel, Sussman & Stacy, 2014).

When it is included to explain sexual behaviors, the effects of sensation-seeking on number of sexual partners and substance use are often explored with inconsistent findings. Greater sensation-seeking is associated with more sexual partners among ethnically diverse adolescents (Oshri et al., 2013; Voisin et al., 2012), African Americans (Byck et al., 2015; Dariotis & Johnson, 2015; Voisin, Hotton, Tan, & DiClemente, 2013) and females (Byck et al., 2015; Voisin, Hotton, Tan, & DiClemente, 2013). Whereas Voisin et al. (2012) found that sensation-seeking is significantly associated with alcohol use regardless of gender, Byck et al. (2015) observed this relationship among females only. Oshri et al. (2013) found that the path from sensation-seeking and alcohol use to number of sexual partners was stronger albeit insignificant for males than females. In samples of young men who have sex with men, Newcomb, Clerkin and Mustanski (2011) found that sensation-seeking moderated the relationship between substance use and risky sexual behavior, but Puckett, Newcomb, Garofalo and Mustanski (2017) found that it had neither a main nor moderating effect on sexual behavior.

Theoretical framework: Problem-Behavior Theory

According to Problem-Behavior Theory, an adolescent’s social and perceived environments, personality, and other behaviors need to be considered collectively in order to understand why some adolescents participate in multiple and potentially health-compromising behaviors (Jessor, 1991). CHS youth are exposed to an environment where substance use (CDC, 1999; Tortolero et al., 2008) and sexual behaviors (e.g., earlier age at sexual onset, multiple sexual partners; CDC, 1999; Coyle et al., 2006; Coyle et al., 2013; Tortolero et al., 2008) are high. CHS youth exhibit high sensation-seeking and tend towards thrill-seeking experiences (Pokhrel, Sussman & Stacy, 2014). However, the pathways of substance use and sensation-seeking during adolescence on subsequent sexual behaviors through young adulthood among CHS youth are not well understood and warrant exploration.

Hypotheses

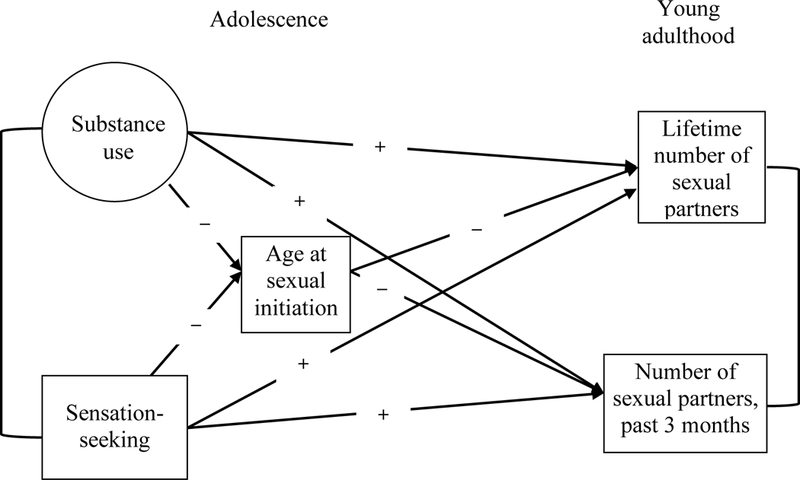

In order to understand sexual risk behaviors among CHS youth, this study tests the paths of adolescent substance use and sensation-seeking on age at sexual onset and subsequent number of sexual partners using a hypothesized structural equation model (Figure 1). Three hypotheses guided this study. First, it was hypothesized that young adults from CHS who reported greater substance use (i.e., alcohol, cigarette, and/or marijuana use) in adolescence would be more likely to report a higher number of lifetime and recent sexual partners by young adulthood. Second, it was hypothesized that CHS young adults with more sensation-seeking in adolescence would be more likely to report a higher number of lifetime and recent sexual partners at 4-year follow-up. Finally, it was expected that these relationships would be at least partially mediated by age at sexual onset where an earlier age at sexual initiation would be associated with greater substance use, more sensation-seeking, and a higher number of sexual partners.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized structural model of the number of sexual partners among young adults from continuation high schools.

Methods

Participants and procedures

The present study used baseline and 4-year follow-up data from a sample of young adults originally recruited from 14 continuation high schools in southern California. The sample originally participated in a study to explore the effects of a skills-based intervention aimed at altering substance use perceptions on CHS youth (Sussman, Dent, & Stacy, 2002; Valente et al., 2007). For the present study, sampling was limited to persons who were at least 18 years old at the time of sampling and self-identified as Latino/a, White, or African American (N = 747). Whites, African Americans and females were oversampled in order to conduct comparative analyses by race/ethnicity and gender. The sample size was further limited to individuals who had reliable contact information in the participant database and the name of at least one parent/guardian for whom an online search could be made for additional information. Given the additional criteria, the final base sample was 391 CHS youth. Probability sampling was initially conducted to obtain a random sample of CHS youth. However, reaching potential participants proved to be challenging (e.g., lost to follow-up, did not return calls), and therefore, a convenience sample of 111 who were accessible were interviewed for the follow-up study.

Self-administered paper-and-pencil baseline surveys (N = 894) were completed in English in the classrooms at the respective CHS. For the 4-year follow-up study, a letter signed by the principal investigator of the parent study was sent to all eligible individuals (N = 391) notifying them of the telephone-based follow-up study. Potential participants were given the ability to opt-out of being contacted by study staff by returning a postage-paid postcard by a designated date indicating their decision to not participate. Those persons who did not actively refuse to be contacted were eligible for the study.

Online database searches (e.g., White Pages, PeopleFinders) were made using the names of the parent(s) or guardian(s) and the participant to update addresses and phone numbers. Reverse searches by address and phone numbers listed in the participant database were also conducted in the White Pages database. If available, phone calls to contacts listed in the participant database were made. Participants were considered lost to follow-up if the address and phone number listed in the participant database were no longer valid, and updated information was not available for both the parent or guardian and participant. Participants were considered “unable to reach” if phone calls were not returned; there was never any answer; or no phone number was listed publicly. A minimum of 10 phone call attempts was made to each participant, but messages were left only at every third call or after a few weeks of leaving a last message.

Once the participant was reached by telephone, an initial screener with verbal consent was read giving basic information on the purpose of the assessment. The 15-minute survey was administered by a trained interviewer once the participant consented verbally to participate. Participants were given the same unique identification number so that the first and second waves of data could be linked. To minimize response biases and prior to asking the sexual behaviors questions, participants were reminded that their name is not written on the survey, and they can refuse to answer any question. A $15 gift card was mailed to each participant for any out-of-pocket expenses related to completing a survey. Raw data were entered into an Access database which was then imported into SAS. All materials and procedures at both waves of data collection received human subjects’ approval from the university’s Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Demographics.

Age.

Age in years at the time of the 4-year follow-up assessment was computed using birth date and follow-up interview date and treated as a continuous variable.

Gender and race/ethnicity.

Information on self-reported gender and race/ethnicity were collected during the baseline assessment (Valente et al., 2007). Gender and race/ethnicity were dichotomously coded. Females were coded as ‘0;’ males were coded as ‘1.’ Latinos (‘1’) were compared to non-Latinos (‘0’).

Sexual behavior orientation.

Sexual behavior orientation was defined using four variables: self-identified sexual orientation; subject’s gender; and reported gender(s) of lifetime and recent sexual partners. The three sexual behavior orientation categories were men who had sex with both men and women (‘1’), women who had sex with men and/or women (‘2’), and men who had sex with women (‘3’). If a male self-identified as “heterosexual” but engaged in sex with both males and females, then he was coded as behaviorally having had sex with both men and women (‘1’).

Substance use.

Information on lifetime use of alcohol, marijuana, and cigarettes was collected at baseline only using an 11-point scale measuring the number of times each drug was used. The scale ranged from 0 (‘1’) to 91 and more times (‘11’), using intervals of 10 and with a higher number indicating greater substance use (Graham et al., 1984). For the baseline sample with available data (N = 873), the substance use measures were reliable (α = 0.79). For the present study, substance use by type was assessed as a continuous variable. In descriptive statistics, alcohol, marijuana, and cigarettes were assessed separately. In an exploratory factor analysis to select reliable items, alcohol, marijuana and cigarettes loaded onto one factor with a minimum factor loading of 0.40. The final substance use scale (Cronbach α = 0.82) was the sum of the three retained substances and thus treated as a latent factor in structural equation modeling.

Sensation-seeking.

Assessment of sensation-seeking was conducted at baseline only. The sensation-seeking scale from the Zuckerman-Kuhlman Personality Questionnaire consisted of five items embedded within 19 statements asked in a True (‘1’)/False (‘0’) format (Zuckerman, Kuhlman, Thornquist, & Kiers, 1991). The sensation-seeking items pertained to enjoyment of “new and exciting experiences and sensations” regardless of fear; enjoy doing things for thrill or doing things that can be frightening; doing “crazy things for fun;” and preferring unpredictable friends. Using a minimum standardized factor loading of .40 in exploratory factor analysis (Brown, 2006), the first four items loaded onto one factor whereas the last item (preferring unpredictable friends) loaded onto a separate factor. Therefore, the final sensation-seeking scale (Cronbach α = 0.67) consisted of the weighted sum of the values of the first four variables and ranged from ‘0’ (no sensation-seeking) to ‘4’ (high sensation-seeking).

Age at sexual onset.

Age at sexual debut was assessed at 4-year follow-up using an ordinal question from YRBS that ranged from ‘1’ (11 years old or younger) to ‘7’ (17 years old or older; CDC, 2008). A lower age indicates a younger age at sexual initiation. It was treated as a mediator between substance use and sensation-seeking and numbers of sexual partners.

Sexual partners.

Lifetime and recent (i.e., past 3 months) numbers of sexual partners were assessed as separate, open-ended outcome variables. These items were modified from YRBS (CDC, 2008) and collected during the 4-year follow-up study. Sexual partners were defined as any partner with whom the participant engaged in anal, receptive oral, and/or vaginal intercourse in one’s lifetime and in the past 3 months. Higher numbers indicate greater numbers of lifetime and recent sexual partners. The number of recent partners was coded as ‘0’ for participants who had sex but not recently.

Data analyses

Since baseline data were nested within schools, intraclass correlation (ICC) coefficients were computed on each dependent variable to address the potential cluster effect of schools. All ICCs were found to be less than 0.03, indicating low degree of dependence in observations (Murray and Blitstein, 2003). Also 4-year follow-up data were collected when the participant was no longer in school, providing further support that controlling for school may not be pivotal in the present analyses. Therefore, structural equation modeling was performed without accounting for school.

Additionally, participants in the parent study were randomized into one of three conditions (i.e., one control group; two treatment conditions) of a substance abuse prevention program. Their participation could have influenced their substance-using behaviors and number of sexual partners at 4-year follow-up. Baseline data on substance use and sensation-seeking were collected prior to participating in the intervention. Thus, these data would not be biased by the treatment condition. Furthermore findings from Tortolero et al. (2008), Coyle et al. (2006) and Coyle et al.’s (2013) sexual risk-reduction interventions with CHS youth show that the intervention effects are short-term and no longer evident beyond 6 months, providing support that controlling for the treatment condition on 4-year outcomes is not necessary in the present analyses. Therefore, structural equation modeling was conducted without accounting for treatment condition.

Attrition analyses were conducted to assess any differences between the baseline and 4-year follow-up samples that may bias the results. To evaluate differential attrition, independent sample t-tests and Chi-square tests were conducted on gender; race/ethnicity; alcohol, cigarette and marijuana use; and sensation-seeking.

Frequency distributions, means, standard deviations, medians, and quartiles were computed to describe demographics, substance use, sensation-seeking, and sexual behaviors. Pearson’s correlation coefficients and Kendall’s tau-b coefficients were calculated to explore bivariate relationships among study variables. Exploratory factor analyses were used to determine the relationships between the observed substance use and sensation-seeking variables and their underlying construct. The criterion for statistical significance was set to a 0.05 level. Measures of reliability, descriptive statistics, correlations, and exploratory factor analyses were computed using SAS version 9.4.

The hypothesized model was tested via structural equation modeling using maximum-likelihood parameter estimation in EQS version 6.1. The relationships of alcohol, marijuana, and cigarette use to its respective latent factor of substance use were assessed empirically through confirmatory factor analyses. Following inspection of confirmatory factor analysis results to verify the presence of a distinct substance use construct, causal pathways were inserted to delineate the relationships among substance use, sensation-seeking, age at sexual onset, and number of lifetime and recent sexual partners. It was further hypothesized that substance use and sensation-seeking as well as numbers of lifetime and recent sexual partners would be correlated. Assessment of model fit was performed using the goodness-of-fit Chi-square test statistic as well as the comparative fit index (CFI) and root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA). A CFI of 0.90 or more and an RMSEA of less than 0.05 is considered to be a good fit (Browne & Cudeck, 1993; Kline, 2005).

Results

A total of 111 young adults completed a follow-up survey. Compared to the baseline sample (N = 894), the 4-year follow-up sample had significantly more females [χ2(1, N = 886) = 5.96, p = .01] and Whites and fewer African Americans and Latinos [χ2(6, N = 857) = 83.89, p <.0001]. The 4-year follow-up sample also reported using significantly more alcohol [t(885) = −3.21, p <.01], cigarettes [t(876) = −3.75, p < .01] and marijuana [t(884) = −2.21, p = .03] at baseline. No significant differences in sensation-seeking [t(844) = 1.61, p = .11] were observed. Racial/ethnic and gender differences were expected given the sampling approach. However, the 4-year follow-up sample reported significantly more substance use and is not comparable to the baseline sample.

The sample was 51% female, 56.8% Latino, and heterosexual (96.4%) with a mean age of 20.6 years (Table 1). The majority of the sample (98.2%) had sexual intercourse with a median age of 15 years at sexual onset. About 23% (N = 25) initiated sex by 13 years of age. Two individuals reported never having sex; one individual was an outlier. Thus, these participant data were omitted from analyses pertaining to sexual behaviors.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the sample

| Variable |

Overall N=111 |

Female N=56 (50.5%) |

Male N=55 (49.5%) |

Latino N=63 (56.8%) |

Non-Latinoa N=48 (43.2%) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | ||

| Ever had sex | 109 | (98.2) | 55 | (98.2) | 54 | (98.2) | 61 | (96.8) | 48 | (100.0) | |

| Sexual behavior orientation | |||||||||||

| Men who have sex with men | 4 | (3.6) | --- | --- | 4 | (7.3) | 3 | (4.8) | 1 | (2.1) | |

| Women who have sex with men | 56 | (50.5) | 56 | (100.0) | --- | --- | 33 | (52.4) | 23 | (47.9) | |

| Men who have sex with women | 51 | (45.9) | --- | --- | 51 | (92.7) | 27 | (42.9) | 24 | (50.0) | |

| Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | Range | |

| Age (years) | 20.56 | (1.24) | 20.27 | (1.27) | 20.85 | (1.14) | 20.57 | (1.19) | 20.54 | (1.32) | 18–23 |

| Substance use | |||||||||||

| Alcohol | 5.72 | (3.79) | 5.16 | (3.71) | 6.29 | (3.83) | 4.67 | (3.71) | 7.10 | (3.48) | 1–11 |

| Cigarettes | 5.06 | (4.09) | 4.88 | (3.97) | 5.24 | (4.24) | 3.08 | (2.71) | 7.65 | (4.16) | 1–11 |

| Marijuana | 5.66 | (4.40) | 4.89 | (4.08) | 6.44 | (4.61) | 3.96 | (3.90) | 7.90 | (4.04) | 1–11 |

| Sensation-seeking | 2.35 | (0.86) | 2.38 | (0.82) | 2.32 | (0.89) | 2.17 | (0.89) | 2.59 | (0.76) | 0–4 |

| Median | (Q1,Q3) | Median | (Q1,Q3) | Median | (Q1,Q3) | Median | (Q1,Q3) | Median | (Q1,Q3) | Range | |

| Age at sexual onset (years; n=109) | 15 | (13, 16) | 15 | (14, 16) | 15 | (13, 16) | 16 | (14, 16) | 14 | (13, 16) | 1–7 |

| Number of sexual partners | |||||||||||

| Lifetime (n=108) | 6 | (3, 8) | 4 | (3, 8) | 7 | (5, 10) | 5 | (3, 7) | 7 | (5, 10) | 1–25 |

| Past 3 months (n=103) | 1 | (1, 2) | 1 | (1, 1) | 1 | (1, 2) | 1 | (1, 1) | 1 | (1, 2) | 1–5 |

Includes 2 African American females.

Alcohol, cigarette and marijuana use and numbers of sexual partners were highly correlated (Table 2). Non-Latino participants reported more substance use, higher sensation-seeking and more lifetime sexual partners than Latinos who had a later age at sexual onset. Males reported more sexual partners than females; otherwise, there were no differences in substance use, sensation-seeking and age at sexual debut. Participants with greater sensation-seeking during adolescence reported more cigarette use but not more alcohol or marijuana use. Individuals who initiated sex at an earlier age reported more sexual partners, alcohol use and marijuana use; a marginal correlation exists between an early age at sexual onset and cigarette use.

Table 2.

Bivariate correlations among study variables.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gendera | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 2. Race/ethnicity | -.04 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 3. Alcohol use | .13 | -.29*** | 1.00 | ||||||

| 4. Marijuana use | .15 | -.40*** | .65*** | 1.00 | |||||

| 5. Cigarette use | .02 | -.42*** | .54*** | .62*** | 1.00 | ||||

| 6. Sensation-seeking | -.02 | -.24*** | .08 | .14 | .24*** | 1.00 | |||

| 7. Age at sexual onsetb | -.09 | .22*** | -.19* | -.20* | -.18† | -.12 | 1.00 | ||

| 8. Number of lifetime sexual partnersb | .29*** | -.29*** | .17† | .17† | .03 | .07 | -.37*** | 1.00 | |

| 9. Number of recent sexual partnersb | .23* | -.13 | .06 | .04 | -.02 | -.09 | -.26*** | .40*** | 1.00 |

For correlations with dichotomous variables, Kendall’s tau-b was used. Otherwise, Pearson’s R was used.

Limited to those who have ever had sexual intercourse (n=109).

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

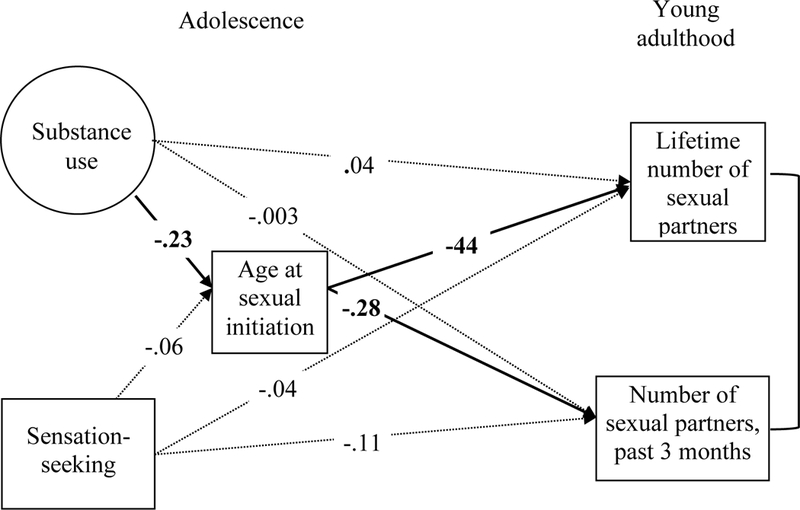

The measurement model was tested using confirmatory factor analyses (Figure 2). Alcohol (0.75), marijuana (0.85), and cigarette use (0.73; p < .05) loaded significantly onto the substance use factor providing evidence of convergent validity (Kline, 2005). Substance use and sensation-seeking were not correlated. The structural model yielded a statistically satisfactory fit to the data (χ2 = 6.49, df = 9, p = .69) and an overall good fit based on the fit indices (CFI = 1.0; RMSEA = 0.000, 90% confidence interval = 0.000, 0.084). Therefore, data analysis moved forward using this model. The standardized path coefficients from the predictors to numbers of sexual partners ranged from −0.003 to −0.44.

Figure 2.

Standardized parameter estimates for the theoretical model of the number of sexual partners among young adults from continuation high schools. Note. Solid lines and bold numbers indicate significant paths and coefficients. Dashed lines indicate non-significant paths. χ2 = 6.49, df = 9, p = .69 CFI = 1.0; RMSEA = 0.000, 90% confidence interval = (0.000, 0.084)

The relationships between substance use and numbers of sexual partners were fully mediated by age at sexual onset. Young adults who reported higher baseline substance use had an earlier age at sexual onset (β = −.23; p < .05), and an earlier age at sexual debut was associated with more lifetime (β = −.44; p < .05) and recent (β = −.28; p < .05) sexual partners. Substance use did not have a significant direct effect on either lifetime or recent sexual partners. Sensation-seeking did not have any direct or indirect effects on age at sexual onset and numbers of sexual partners.

Discussion

It was hypothesized that more substance use or higher sensation-seeking during adolescence would be predictive of greater numbers of sexual partners at 4-year follow-up, and these relationships would be minimally partially mediated by an earlier age at sexual onset. Inconsistent with the literature, there were no direct effects of adolescent substance use on numbers of sexual partners through young adulthood. The relationships between substance use and numbers of sexual partners were fully mediated by age at sexual initiation. CHS youth who reported greater substance use during adolescence were more likely to initiate sex at an earlier age. Early initiation of both activities was predictive of the number of lifetime and recent sexual partners by young adulthood.

Although substance use did not have a direct effect on the numbers of sexual partners in a structural equation model, alcohol and marijuana use were marginally correlated with more lifetime sexual partners. Cavazos-Rehg et al. (2011), McGuire, Wang & Zhang (2012), and Vasilenko & Lanza (2014) observed significant relationships between cigarette use and number of sexual partners. However in the present study, cigarette use was not correlated with numbers of sexual partners but was marginally correlated with an earlier age at sexual onset. In his review of the literature, Sussman (2005) found significant associations between cigarette smoking and risky sexual behavior (i.e., being sexually active; early sexual onset) and theorizes that the link between the two behaviors could be the result of behavioral disinhibition. Given the findings from the present study, cigarette smoking like alcohol and marijuana use may provide behavioral disinhibition to initiate sex at a younger age which is then a stronger predictor of lifetime number of sexual partners, providing longitudinal empirical support to supplement Sussman’s (2005) review.

Unlike prior research that found a significant relationship between sensation-seeking and number of sexual partners (Byck et al., 2015; Oshri et al., 2013; Voisin et al., 2012), the present study with a greater at-risk sample did not find a significant relationship but rather a marginal association. Pokhrel, Sussman and Stacy (2014) found no long-term effect of sensation-seeking on cigarette use in a sample of CHS youth and theorized that sensation-seeking may be more likely to be associated with initiation or maintenance of versus increased substance use. In the present study, CHS youth with higher sensation-seeking scores may be more likely to initiate sex at a younger age than lower sensation-seekers. Sensation-seeking may also indirectly impact the number of sexual partners through other aspects of it (e.g., impulsivity in Puckett et al. (2017)).

Additionally, significant bivariate relationships by key demographic variables existed. Unlike the results from ALT-YRBS (CDC, 1999) that showed interactions of substance use by race/ethnicity and gender, alcohol, cigarette and marijuana use were significantly higher among non-Latino/a, predominantly White youth than Latino youth in the present study, and there were no gender differences. Males and early sexual initiators had greater numbers of sexual partners. Other factors may contribute to more sexual partners among males and reinforce their sexual practices. Early initiation to sexual activity provides a longer period of time for sexual behaviors to occur including having sexual relationships with multiple partners.

Limitations

Despite the study findings, several limitations need to be considered. First, attrition was high. Given the inclusion criteria and accessing former CHS youth who had some contact information on which additional searches could be made, access to the baseline sample was immediately reduced to 52.3% of which 28.4% completed a 4-year follow-up survey. Although efforts were taken to contact a larger and random sample size, tracking participants proved to be difficult, supporting what other researchers who have worked with CHS youth have noted (Coyle et al., 2006; Sussman, Dent & Stacy, 2002; Tortolero et al., 2008). The present sample was not a representative sample of the larger base sample since it was a convenience sample and substance use varied significantly. Additionally, baseline participants who were not interviewed in the present study may have sexual behaviors that differ from the present sample thereby limiting the generalizability of the findings. However, a strength of the present study was the ability to interview former CHS youth with high substance use and knowing its subsequent effects on sexual behaviors.

Second, substance use and sensation-seeking were not measured at 4-year follow-up. Current cigarette, alcohol and marijuana use may be higher and sensation-seeking may be lower than baseline values since the sample is older. All participants were of legal age to purchase cigarettes, and thus, cigarette use may be higher. With an average sample age of 20.5 years, some individuals could legally purchase alcohol or may have greater access to it. Sensation-seeking has been shown to have a curvilinear trajectory, peaking during adolescence and either decreasing or remaining stable through young adulthood (Steinberg et al., 2008), and can be lower. The unavailability of these current measures limits the ability to address how sensation-seeking impacts substance use over the 4-year period. Furthermore, the causal model needs to be interpreted with caution given the 4-year time lag between predictor and outcome variables. Unaccounted intrapersonal (e.g., impulsivity), interpersonal (e.g., experiences of abuse and trauma) and environmental (e.g., condom availability and affordability) factors may impact sexual behaviors. The model in the present study is a simple cause-and-effect model between substance use, sensation-seeking and sexual behaviors; however it is an important model in light of the paucity of literature on CHS youth.

Validity of the data could also be affected by the self-report nature of the study, especially with sensitive questions on sexual behaviors. Participants were assured of the confidentiality of all data, and measures were taken before and during survey administration to emphasize this confidentiality. Furthermore, measures that were used had been validated previously in adolescent samples. Therefore, there is no reason to believe that participants were differentially dishonest in their answers.

Despite these limitations, results from this study support the effect of early sexual onset on subsequent sexual risk-taking. Results highlight an important pathway between substance use and age at sexual initiation during adolescence on the number of sexual partners by young adulthood. Further research is warranted to understand the pathways by which sensation-seeking and sexual risk-taking occurs among former CHS youth. These conclusions bear potential implications for the prevention of sexual risk-taking with the potential for harmful health outcomes. Interventions aimed at CHS youth could benefit by incorporating comprehensive sexual education into substance abuse prevention curriculum. Future research is needed to determine whether this type of intervention can reduce sexual risk-taking among this at-risk population.

Glossary

- Adolescents

individuals typically between the ages of 13 and 18 years

- Continuation high schools

alternative schools with specialized skills for students who are at risk of not graduating from high school

- Sensation-seeking

personality trait characterized by a tendency to seek varied and thrilling experiences and possibly take risks to encounter them

- Sexual behaviors

global phrase that includes age at sexual onset and numbers of lifetime and recent sexual partners with whom a person has engaged in anal, receptive oral, and/or vaginal intercourse

- Sexual onset

age at which a person first initiated or engaged in sexual intercourse

- Substance use

use of licit or illicit drugs (e.g., alcohol, cigarettes, marijuana)

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Brown TA (2006). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York, NY: The Guildford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Browne M, & Cudeck R (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit In Bollen K & Long J (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136–162). Newbury Park: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Burt RD, Dinh KT, Peterson JAV, & Sarason IG (2000). Predicting adolescent smoking: A prospective study of personality variables. Preventive Medicine, 30, 115–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byck GR, Swann G, Schalet B, Bolland J, & Mustanski B (2015) Sensation seeking predicting growth in adolescent problem behaviors. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 46, 466–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Kerr DCR, Owen LD, & Tiberio SS (2017). Intergenerational associations in sexual onset: Mediating influences of parental and peer sexual teasing and youth substance use. Journal of Adolescent Health, 61, 342–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavazos-Rehg PA, Krauss MJ, Spitnagel EL, Schootman M, Cottler LB, & Bierut JJ (2011). Number of sexual partners and associations with initiation and intensity of substance use. AIDS and Behavior, 15(4), 869–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1999). Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance – National Alternative High School Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 1998. MMWR, 48(SS07), 1–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2000). Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance –United States, 1999. MMWR, 49(SS05), 1–104. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2008). 2007 State and Local Youth Risk Behavior [Survey]. Retrieved from ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/data/yrbs/2007/2007_hs_questionnaire.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2015). HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report, 2014, Vol. 26 Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Coyle KK, Kirby DB, Robin LE, Banspach SW, Baumler E, & Glassman JR (2006). All4You! A randomized trial of an HIV, other STDs, and pregnancy intervention for alternative school students. AIDS Education and Prevention, 18(3), 187–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle KK, Glassman JR, Franks HM, Campe S, Denner J, & Lepore G (2013). Interventions to reduce sexual risk behaviors among youth in alternative schools: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53(1), 68–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockett LJ, Raffaelli M, & Shen YL (2006). Linking self-regulation and risk proneness to risky sexual behavior: pathways through peer pressure and early substance use. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 16, 503–525. [Google Scholar]

- Dariotis JK, & Johnson MW (2015). Sexual discounting among high-risk youth ages 18–24: Implications for sexual and substance use risk behaviors. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 23(1), 49–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demissie Z, Everett Jones S, Clayton HB, & King BA (2017). Adolescent risk behaviors and use of electronic vapor products and cigarettes. Pediatrics, 139(2), 2016–2921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon FR, de la Rosa M, Schwartz SJ, Rojas P, Duan R, & Malow RM (2010). U.S. Latina age of sexual debut: Long-term associations and implications for HIV and drug abuse prevention. AIDS Care, 22(4), 431–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doran KA, & Waldron M (2017). Timing of first alcohol use and first sex in male and female adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 61, 606–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein M, Bailey JA, Manhart LE, Hill KG, Hawkins JD, … Catalano RF (2014). Understanding the link between early sexual initiation and later sexually transmitted infection: Test and replication in two longitudinal studies. Journal of Adolescent Health, 54, 435–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd LJ, & Latimer W (2010). Adolescent sexual behaviors at varying levels of substance use frequency. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse, 19(1), 66–77. [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW, Flay BR, Johnson CA, Hansen WB, Grossman L, & Sobel JL (1984). Reliability of self-report measures of drug use in prevention research: evaluation of the project SMART questionnaire via the test-retest reliability matrix. Journal of Drug Education, 14, 175–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green KM, Musci RJ, Matson PA, Johnson RM, Reboussin BA, & Ialongo NS (2017). Developmental patterns of adolescent marijuana and alcohol use and their join association with sexual risk behavior and outcomes in young adulthood. Journal of Urban Health, 94, 115–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R (1991). Risk behavior in adolescence: A psychosocial framework for understanding and action. Journal of Adolescent Health, 12(8), 597–605. DOI: 10.1016/1054-139X(91)90007-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan DL, Jones EJ, Olson C, & Yunzal-Butler C (2013). Early age of first sex and health risk in an urban adolescent population. Journal of School Health, 83(5), 350–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB (2005). Principles and practices of structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guildford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kong G, Smith AE, McMahon TJ, Cavallo DA, Schepis TS, … Krishnan-Sarin S (2013). Pubertal status, sensation-seeking, impulsivity, and substance use in high-school-aged boys and girls. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 7(2), 116–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan PP, Sussman S, & Valente T (2015). Peer leaders and substance use among high-risk adolescents. Substance Use & Misuse, 50(3), 283–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry R, Dunville R, Robin L, & Kann L (2017). Early sexual debut and associated risk behaviors among sexual minority youth. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 52(3), 379–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry R, Robin L, & Kann L (2017). Effect of forced sexual intercourse on associations between early sexual debut and other health risk behaviors among US high school students. Journal of School Health, 87(6), 435–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnusson BM, Nield JA, & Lapane KL (2015). Age at first intercourse and subsequent sexual partnering among adult women in the United States, a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 15(98), 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire J, Wang B, & Zhang L (2012). Substance use and sexual risk behaviors among Mississippi public high school students. Journal of the Mississippi State Medical Association, 53(10), 323–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mott FL, Fondell MM, Hu PN, Kowaleski-Jones L, & Menaghan EG (1996). The determinants of first sex by age 14 in a high-risk adolescent population. Family Planning Perspectives, 28(1), 13–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray DM, & Blitstein JL (2003). Methods to reduce the impact of intraclass correlation in group-randomized trials. Evaluation Review, 27(1), 79–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers R, Chou CP, Sussman S, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Pachon H, & Valente TW (2009). Acculturation and substance use: Social influence as a mediator among Hispanic alternative high school youth. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 50(2), 164–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Educational Statistics (2012). Number and enrollment of public elementary and secondary schools, by school level, type, and charter and magnet status: Selected years, 1990–91 through 2010–11 [Data file]. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d12/tables/dt12_108.asp.

- Newcomb ME, Clerkin EM, & Mustanski B (2011). Sensation seeking moderates the effects of alcohol and drug use prior to sex on sexual risk in young men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior, 15, 567–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshri A, Handley ED, Sutton TE, Wortel S, & Burnette ML (2014). Developmental trajectories of substance use among sexual minority girls: Associations with sexual victimization and sexual health risk. Journal of Adolescent Health, 55(1), 100–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshri A, Tubman JG, Morgan-Lopez AA, Saavedra LM, & Csizmadia A (2013). Sexual sensation seeking, co-occuring sex and alcohol use, and sexual risk behavior among adolescents in treatment for substance use problems. The American Journal on Addictions, 22, 197–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokhrel P, Herzog TA, Sun P, Rohrbach LA, & Sussman S (2013). Acculturation, social self-control, and substance use among Hispanic adolescents. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 27(3), 674–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokhrel P, Sussman S, & Stacy AW (2014). Relative effects of social self-control, sensation seeking, and impulsivity on future cigarette use in a sample of high-risk adolescents. Substance Use & Misuse, 49(4), 343–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puckett JA, Newcomb ME, Garofalo R, & Mustanski B (2017). Examining the conditions under which internalized homophobia is associated with substance use and condomless sex in young MSM: The moderating role of impulsivity. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 51, 567–577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggs NR, Tate EB, Ridenour TA, Reynolds M, Zhai ZW, … Tarter RE (2013). Longitudinal associations from neurobehavioral disinhibition to adolescent risky sexual behavior in boys: Direct and mediated effects through moderate alcohol consumption. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53(4), 465–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santelli JS, Kaiser J, Hirsch L, Radosh A, Simkin L, & Middlestadt S (2004). Initiation of sexual intercourse among middle school adolescents: The influence of psychosocial factors. Journal of Adolescent Health, 34, 200–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Albert D, Cauffman E, Banich M, Graham S, & Woolard J (2008). Age differences in sensation seeking and impulsivity as indexed by behavior and self-report: Evidence for a dual systems model. Developmental Psychology, 44(6), 1764–1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussman S (2005). The relations of cigarette smoking with risky sexual behavior among teens. Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity, 12, 181–199. [Google Scholar]

- Sussman S (1996). Development of a drug abuse prevention curriculum for high risk youth. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 28, 169–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussman S, Dent CW, & Stacy A (2002). Project Towards No Drug Abuse: A review of the findings and future directions. American Journal of Health Behavior, 26(5), 354–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tortolero SR, Markham CM, Addy RC, Baumler ER, Escobar-Chaves SL, Basen-Engquist KM … Parcel GS (2008). Safer choices 2: Rationale, design issues, and baseline results in evaluating school-based health promotion for alternative school students. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 29, 70–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner AK, Latkin C, Sonenstein F, & Tandon SD (2011). Psychiatric disorder symptoms, substance use, and sexual risk behavior among African American out of school youth. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 115, 67–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valente TW, Ritt-Olson A, Stacy A, Unger JB, Okamoto J, & Sussman S (2007). Peer acceleration: Effects of a social network tailored substance abuse prevention program among high-risk adolescents. Addiction, 102(11), 1804–1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasilenko SA, & Lanza ST (2014). Predictors of multiple sexual partners from adolescence through young adulthood. Journal of Adolescent Health, 55, 491–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voisin DR, Hotton A, Tan K, & DiClemente RJ (2012). A longitudinal examination of risk and protective factors associated with drug use and unsafe sex among young African American females. Child and Youth Services Review, 35(9), 1440–1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voisin DR, King K, Schneider J, DiClemente RJ, & Tan K (2012). Sexual sensation seeking, drug use and risky sex among detained youth. Journal of AIDS & Clinical Research, S1, 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman M, Kuhlman DM, Thornquist M, & Kiers H (1991). Five (or three) robust questionnaire scale factors of personality without culture. Personality and Individual Differences, 12, 929–941. [Google Scholar]