Abstract

Background:

Reported revision rates for endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) for chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) vary significantly. Several investigations examining revision rates for ESS have been limited by duration of follow up, academic centers, or small surgeon cohorts. The objective of this study was to define the long-term revision rates for ESS and to determine those unique patient factors that increase the risk of revision ESS.

Methods:

The Utah Population Database was queried for Current Procedural Terminology codes for ESS from 1996 to 2016. Patient demographics and comorbid diagnoses were collected. Revision rates and risk factors for surgery were determined by Cox Proportional Hazard modeling.

Results:

A total of 29,934 patients were identified, with a mean length of follow up of 9.7 years. The long-term revision rate was found to be 15.9%. The mean time between surgeries decreased with higher number of revision surgeries. The time between the 1st and 2nd surgery was 4.39 years and the time between the 4th and 5th surgery decreased to 2.18 years. Female gender, older age at first surgery, nasal polyps, comorbid asthma, allergy and a family history of CRS all increased the risk of requiring revision surgery (p<0.001).

Conclusions:

The long-term revision rate for ESS exceeds 15% and the time between revision surgeries decreased with each additional surgery being performed. Unique patient factors increased the risk of requiring revision ESS. Understanding patients’ risk for revision surgery may help physicians select and counsel patients with CRS undergoing ESS.

Keywords: chronic rhinosinusitis, endoscopic sinus surgery, revision surgery, risk factors, patient factors

Introduction

Endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) is one of the most common surgical procedures in the United States, with over 250,000 cases performed annually.1 Many of these cases are performed for medically recalcitrant chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) but despite the volume of cases, the revision rates for ESS are unclear. Previous literature on these revision rates varies significantly, with revision rates as low as 4% and as high as 19.1%.2–4 The time between revision surgeries is similarly confounding – the duration between surgeries ranges anywhere from 1 to 10 years.5 Patient factors that increase the risk for revision surgery have been identified as well and include a history of asthma, nasal polyps, or aspirin sensitivity.3,6 Recently, gender has been implicated as a potential risk factor as well.3

Several of these previous investigations have been limited by a short duration of follow up as well as small surgeon cohorts.4 Many of these studies examine 5 year periods, while CRS is associated with a long-term burden of disease. In the longitudinal research studies, many patients are lost to follow up, which may bias results towards more severe disease.7 Additionally, ESS is a highly varied procedure and the revision rates for specific sinuses are unknown. These factors make it difficult to determine the overall long-term revision rates for ESS and challenging to identify patients who may be at risk for long-term revision ESS. A better understanding of the natural surgical history of CRS is necessary to better inform providers and patients, particularly while focusing on providing high quality care.

The Utah Population Database is a resource that houses data on over 11 million individuals, with over 80 years of multi-generational pedigrees.8 It contains information on all hospital encounters in Utah from birth until death, and presents the unique opportunity to study the long-term natural history of CRS. Additional information including family history of CRS, comorbid asthma and history of tobacco use is also available, which may help to confirm and identify additional risk factors for revision ESS. The objectives of this study, utilizing the Utah Population Database, are to define the long-term revision rates for ESS, determine the mean duration between revision surgeries, determine the revision rates for specific sinuses, and identify patient factors that increase the risk of revision ESS.

Methods

I. Study Design

Utah Population Database

The following paragraph describes in detail the database used for this study. Ambulatory care data was added to the database in 1996.

The UPDB ambulatory care database was utilized for this study. The UPDB is one of the world’s most robust sources of linked population-based information for demographic, genetic, and epidemiological studies. The UPDB now contains data on over 11 million individuals from the late 18th century to the present. The data grow due to longstanding efforts to update records as they become available including statewide birth and death certificates, hospitalizations, ambulatory surgeries, and driver licenses. UPDB creates and maintains links between the database and the medical records held by the two largest healthcare providers in Utah as well as Medicare claims. The database records physician-patient encounters, which can be categorized by diagnostic as well as common procedural terminology codes. Associated demographic data and comorbid diagnostic codes are available within the database. One of the unique features of the database is it allows for patient specific encounters to be tracked. For example, a patient identified in the database can be followed throughout their lifetime and care specific to the patient can be identified. This ability to track patient specific information made this study possible. Additionally, the location of the physician-patient interaction does not affect the data collection. Encounters at academic, community, and rural centers are all included as are hospital encounters, surgical centers and in-office procedures. The breadth and longevity of the database provides a unique opportunity to assess the longitudinal natural history of patients who undergo ESS. 8

Study Population

The UPDB was queried for adult patients diagnosed with chronic rhinosinusitis between 1996 and 2016 using a previously validated cohort definition. Patients with ICD9 codes of 473.0, 473.1, 473.2, 473.3, 473.8, and 473.9 as well as CPT codes for sinus surgery (31231, 31237, 31288, 31267, 31233, 31254, 31255, 31256, 31276, and 31287) were identified. Combinations of diagnostic codes and CPT codes (31231, 31237) were utilized to increase the ability to accurately identify patients with CRS. At the time of the first surgery, patients were required to be at least 18 years of age. Patients were excluded if they had any history or diagnosis of malignant sinonasal neoplasms (160.0-160.9), inverted papilloma (212), cystic fibrosis (277), immune disorders (279), congenital craniofacial abnormalities (744), ciliary dyskinesia (759) and a history of head or facial trauma (800.x-804.x, 959.0, 959.01, 959.09). Additionally, patients were excluded if there was no documentation of patient sex or if the date of last follow up in the UPDB preceded the date of first surgery. This excluded patient records that may have documentation errors.

In previous studies examining this cohort of CRS patients in the UPDB, patient records were reviewed from the University of Utah health records and the diagnosis of CRS in the UPDB had a positive predictive value of 90%.9 The ability to differentiate between CRSwNP and CRSsNP based on ICD9 codes and billing codes only in the UPDB was approximately 71%.9

The overall revision rate for this cohort was defined as patients who had an initial episode of sinus surgery (defined by any combination of CPT codes 31288, 31267, 31233, 31254, 31255, 31256, 31276, and 31287) followed by an additional episode of sinus surgery on a different and later date (defined by any combination of CPT codes 31288, 31267, 31233, 31254, 31255, 31256, 31276, and 31287). Subsequent distinct episodes of these codes would be counted as 3rd or 4th revisions etc based on the number of previous surgeries. Specific sinus revision rates were determined by examining repeat occurrences of distinct codes. For example, a patient who has had a frontal sinusotomy (31276) followed by an additional episode of a frontal sinusotomy at a later date would be included as a frontal sinus revision.

II. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated to analyze patient characteristics. Demographic characteristics and percent revision surgeries between CRSsNP and CRSwNP patients were compared using t-tests for continuous variables and chi-squared tests for categorical variables. Cox proportional hazard models were used to estimate the effect of gender, age at diagnosis procedure, race, ethnicity, history of tobacco use, history of allergy, history of asthma, urban location, history of a first degree relative with CRS, and nasal polyps on risk of revision surgeries. Statistical analysis was performed using R software version 3.4.2.

III. Outcomes

The primary outcome of this study was the long-term revision rate for ESS. Additional outcomes include the average number of sinus surgeries for a patient with CRS, revision rates for specific sinuses, the characteristics of primary ESS, the duration of time between surgeries and characteristics that increase patients’ risk for revision surgery.

Results

Review of the database identified 29,934 patients who met inclusion criteria and were included in the analysis. Table 1 outlines the cohort characteristics. Mean duration of follow up in the database was 9.7 ± 4.7 years.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic data for study cohort

| All CRS (n=29934) | CRSsNP (n=20757) | CRSwNP (n=9177) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | < 0.001 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 44.0 (15.1) | 43.6 (15.0) | 44.8 (15.2) | |

| Range | 18.0-95.8 | 18.0-95.8 | 18.0-90.2 | |

| Gender (male) | 48.3% | 45.4% | 55.1% | < 0.001 |

| Race | 0.017 | |||

| White/Caucasian | 92.0% | 92.0% | 91.9% | |

| African American | 0.3% | 0.4% | 0.3% | |

| Asian | 0.8% | 0.8% | 0.8% | |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 0.7% | 0.7% | 0.6% | |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 0.3% | 0.2% | 0.5% | |

| Other/Multiple Races | 0% | 0% | 0.0% | |

| Not Available | 5.9% | 5.9% | 6.0% | |

| Ethnicity | 0.827 | |||

| Hispanic/Latino | 5.5% | 5.6% | 5.4% | |

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 73.8% | 73.7% | 73.9% | |

| Not Available | 20.7% | 20.7% | 20.7% | |

| Urban Location | 71.8% | 70.9% | 73.8% | < 0.001 |

| Asthma | 21.8% | 18.2% | 30.1% | < 0.001 |

| Allergy | 11.4% | 10.8% | 12.6% | < 0.001 |

| Tobacco Use | 16.6% | 16.7% | 16.6% | 0.862 |

The sinuses involved in primary ESS are described in Table 2. The maxillary sinus and ethmoid sinuses (anterior or total) are most commonly addressed in primary ESS (>80% of cases). CRSwNP patients were significantly more likely to have a frontal sinusotomy at their original surgery (p<0.001).

Table 2.

Characteristics of initial endoscopic sinus surgery

| All CRS (n=29934) | CRSsNP (n=20757) | CRSwNP (n=9177) | p value | |

| Maxillary | 44.1% | 50.8% | 28.9% | < 0.001 |

| Maxillary with tissue removal | 44.0% | 37% | 60.0% | < 0.001 |

| Anterior ethmoid | 25.0% | 28.7% | 16.7% | < 0.001 |

| Total ethmoid | 59.5% | 54.1% | 71.5% | < 0.001 |

| Sphenoid | 15.4% | 15.6% | 14.7% | 0.049 |

| Sphenoid with tissue removal | 8.7% | 5.5% | 16.2% | < 0.001 |

| Frontal | 26.4% | 23.7% | 32.4% | < 0.001 |

| Polyp removal (not otherwise specified) | 2.4% | 0% | 7.9% | < 0.001 |

I. Long-Term Revision Rate

The long-term revision rate for ESS for all CRS patients was 15.9%. The mean number of sinus surgeries for all CRS patients is 1.22. CRSsNP patients have a slightly lower number of surgeries (1.12 per patient) while CRSwNP patients have higher rates (1.46 per patient) (p<0.001). This rate includes any sinus surgery following initial surgery, such as a frontal sinusotomy following a maxillary antrostomy and anterior ethmoidectomy, as well as revisions on specific sinuses (i.e. revision frontal sinusotomy). Table 3 outlines the long-term revision rates overall and for specific sinuses. There is a significantly increased percentage of patients who require revision surgery in CRSwNP patients compared to CRSsNP patients overall (p<0.001). Revision rates for specific sinuses were significantly higher in patients with CRSwNP. Revision frontal sinusotomies were performed in 21.1% of CRSwNP patients, compared to only 6.3% of CRSsNP patients (p<0.001).

Table 3.

Long-term revisions for endoscopic sinus surgery and specific sinuses

| All CRS | CRSsNP | CRSwNP | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall* | 15.9% | 9.75% | 29.88% | <0.001 |

| Maxillary | 5.4% | 4.3% | 9.4% | <0.001 |

| Maxillary with tissue removal | 11.1% | 5.4% | 18.4% | <0.001 |

| Anterior ethmoid | 4.2% | 3.1% | 7.7% | <0.001 |

| Total ethmoid | 11.5% | 5.4% | 21.6% | <0.001 |

| Sphenoid | 6.1% | 3.5% | 11.1% | <0.001 |

| Sphenoid with tissue removal | 12.4% | 3.5% | 14.6% | <0.001 |

| Frontal | 12.4% | 6.3% | 21.2% | <0.001 |

| Polyp removal (not otherwise specified) | 8.1% | 0% | 8.1% | <0.001 |

percentage of patients who had more than one ESS in the 20-year study period

The percentage of patients who required revision surgery is outlined in Table 4. The majority of patients who required revision surgery only had one additional surgery (12%). The remaining 3.9% of patients had 2 or more additional surgeries. CRSwNP patients have higher revision rates than CRSsNP. CRSwNP patients had a significantly higher expected number of revision surgeries compared to CRSsNP patients when accounting for all other variables (OR 3.71, p<0.001).

Table 4.

Percentage of patients who underwent multiple endoscopic sinus surgeries over the 20-year study duration

| Number of revision surgeries | All CRS (n=29934) | CRSsNP (n=20757) | CRSwNP (n=9177) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any revision surgery | 15.9% | 9.8% | 29.9% | <0.001 |

| 0 revisions | 84.1% | 90.2% | 70.1% | <0.001 |

| 1 revision | 12.0% | 8.3% | 20.4% | |

| 2 revisions | 2.6% | 1.1% | 6.0% | |

| 3-5 revisions | 1.2% | 0.3% | 3.2% | |

| 6+ revisions | 0.1% | 0% | 0.3% | |

II. Duration between Endoscopic Sinus Surgeries

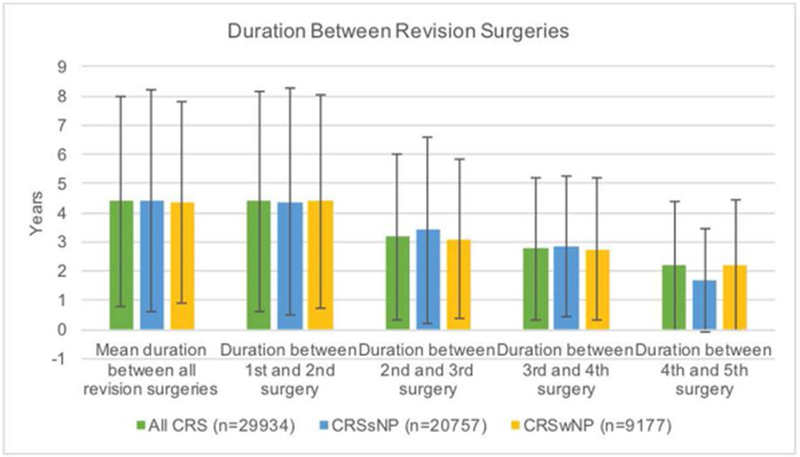

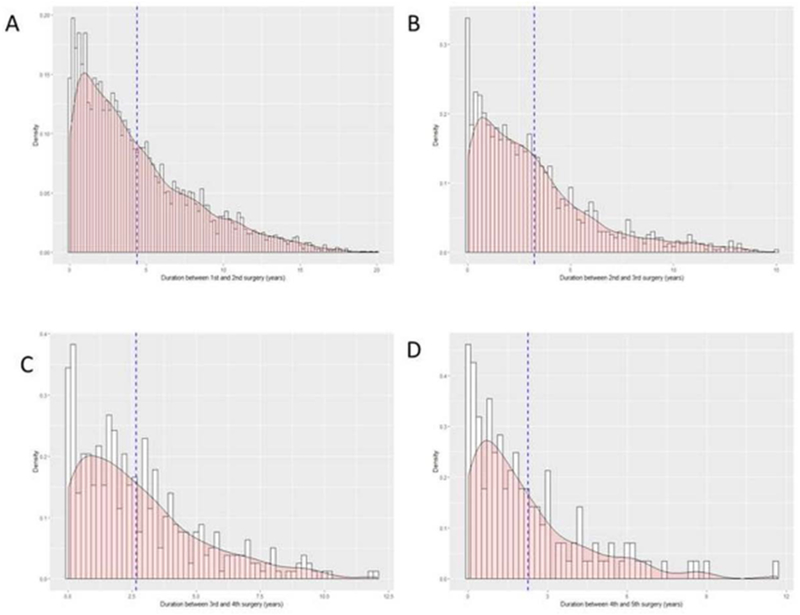

The mean duration between ESS was 4.39 years. As the number of ESS revisions increases, the duration between surgeries decreases (Figure 1). The time between the 1st and 2nd surgery is 4.39 years. The time between surgeries progressively decreases, until the time between the 4th and 5th surgeries is 2.18 years. There is no significant difference between times to revision between CRSsNP and CRSwNP patients. The data for time between each surgery was right-skewed (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Duration between revision surgeries. There was no significant difference between the durations comparing chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis (CRSwNP) versus without nasal polyposis (CRSsNP). Note how duration between revision surgeries decreases as the number of surgeries increases.

Figure 2.

Histogram plots of distribution of duration between surgeries (years) overlaid with density plot and mean line (blue). A. Duration between 1st and 2nd surgeries B. Duration between 2nd and 3rd surgeries C. Duration between 3rd and 4th surgeries D. Duration between 4th and 5th surgeries

III. Patient characteristics that affect revision rates

All of the demographic factors collected and summarized in Table 1 were examined as potential risk factors for revision surgery. The results of this analysis are summarized in Table 5. Race, ethnicity and tobacco use were not associated with an increased risk of revision surgery. Location of patients’ homes was examined by comparing urban to rural locations and location was also not associated with an increased risk of surgery.

Table 5.

Patient characteristics that affect revision rates

| Risk of 2nd Surgery | Risk of 3rd surgery | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Male gender | 0.78 (0.73, 0.82) | <0.001 | 0.90 (0.80, 1.01) | 0.076 |

| Age at 1st procedure | 0.88 (0.86, 0.91) | <0.001 | 0.93 (0.87, 0.99) | 0.029 |

| Race | 1.04 (0.86, 1.26) | 0.701 | 0.91 (0.61,1.35) | 0.633 |

| Ethnicity | 0.91 (0.80, 1.03) | 0.134 | 1.01 (0.78, 1.31) | 0.935 |

| Tobacco Use | 1.02 (0.94, 1.10) | 0.661 | 1.03 (0.89, 1.20) | 0.673 |

| Asthma | 1.61 (1.51, 1.71) | <0.001 | 1.48 (1.32, 1.67) | <0.001 |

| Allergy | 1.40 (1.30, 1.52) | <0.001 | 1.21 (1.05, 1.40) | <0.001 |

| Urban Location | 1.04 (0.98, 1.11) | 0.204 | 1.03 (0.90, 1.17) | 0. 682 |

| Family history of CRS* | 1.14 (1.05, 1.24) | <0.001 | 0.93 (0.79, 1.10) | 0.401 |

| Nasal Polyps | 3.41 (3.21, 3.61) | <0.001 | 2.30 (2.01, 2.63) | <0.001 |

first degree relative with a family history of chronic rhinosinusitis

Shaded cells highlight statistically significant factors

Male gender was found to be a protective factor for the risk of an initial revision surgery (relative risk 0.78, p<0.001). However, when examining the risk of a second revision, or 3rd ESS, gender was no longer a significant predictor.

Younger age at the time of the first ESS was associated with a decreased risk of revision surgery (relative risk 0.88, p<0.001). Age at first surgery remained protective when considering the risks of additional ESS (relative risk 0.93, p<0.001).

A history of asthma, allergy and nasal polyposis were all associated with a significantly increased risk of 2nd and 3rd endoscopic sinus surgery (p<0.001). Nasal polyposis has the largest impact of risk of revision surgery (relative risk 3.41).

A family history of a first degree relative with CRS was associated with an increased risk of a revision ESS (relative risk 1.14, p<0.001). However, similar to gender, family history was no longer associated with increased risk after an initial revision surgery (i.e. 3rd surgery).

Overall, male gender and a younger age at first ESS were protective factors for the risk of revision surgery. Asthma, allergy and nasal polyps were all associated with an increased risk of multiple revision surgeries. A family history of CRS was associated with an increased risk of a single revision surgery. Race, ethnicity and tobacco use were not associated with an increased risk of revision surgery.

Discussion

The objective of this study was to determine the long-term revision rates of ESS for patients with CRS, time between revision surgeries, the revision rates for specific sinuses, and identify patient factors that increase the risk of revision surgery. The overall long-term revision rate for ESS was found to be 15.9%. The revision rates for specific sinuses were examined and vary from 4.2% for the anterior ethmoid sinuses up to 12.4% for the frontal sinus. Of note, all revision rates were higher in patients with CRSwNP versus CRSsNP (p<0.001). The mean time between surgeries decreased with higher number of revision surgeries. The time between the 1st and 2nd surgery was 4.39 years and the time between the 4th and 5th surgery decreased to 2.18 years. There was no difference in the durations between surgeries comparing CRSwNP and CRSsNP. Female gender, older age at first surgery, nasal polyps, comorbid asthma, allergy and a family history of CRS all increased the risk of requiring revision surgery (p<0.001).

An overall long-term revision rate of 15.9% was identified in this study – CRSwNP have higher rates of revision surgery (30%) than CRSsNP (9.75%) (p<0.001). The majority of patients who required revision surgery required only one additional surgery, while a minority (3.9%) went on to require at least 2 additional surgeries. This rate is higher than what has been previously reported in much of the American literature, where overall CRS revision rates were recently reported to be between 4% and 6.65%.3,4 However, these studies may be underreporting revision rates due to their short duration. Miglani et al. reported follow up rates of 4% for their cohort, which had a median follow up of 2.3 years.4 The results from this study suggest that the mean duration between revision ESS is 4.39 years, suggesting their cohort may need to be followed for longer. This may also explain the low revision rates found in their study. Stein et al. identified revision rates of 6.65% in their cohort with a mean follow up of 3.5 years.3 California, the location of their study, has also been identified as an under utilizer of ESS, while Utah is an over utilizer, which may account for some of the difference seen between these two cohorts.10 The findings of this study are more consistent with the result from the UK examination of revision rates, which found revision rates of 19.1%, as well as Wu et al. which reported a mean duration between surgery of 4.87 years.3,11

The duration between multiple surgeries has not been previously defined. The overall duration between revision surgeries was found to be 4.39 years in this study, which is consistent with some previous literature.11 Interestingly, there was no difference in the duration between surgeries between CRSsNP and CRSwNP patients. Another unique finding of this study was the duration between surgeries decreased with each additional surgery. For example, there are approximately 4.39 years between a patient’s 1st and 2nd sinus surgery. However, if that patient requires a 5th ESS, the time between the 4th and 5th surgery is on average only 2.18 years. This is in contrast to the anecdotal idea that the duration between ESS increases, or stays stable. Although, the etiology of this finding is unclear, the data does provide a useful piece of information for patient counselling when revision surgeries are required.

This study additionally identified the sinuses that were most frequently involved in the initial ESS and the revision rates for those sinuses. Greater than 80% of patients have their maxillary sinuses and anterior/total ethmoids addressed in their initial surgery. Approximately 24% of patients have sphenoidotomies and 26% will have frontal sinusotomies during the initial surgery, however CRSwNP patients are more likely to have these sinuses opened during their primary surgery. Revision rates for specific sinuses were consistently higher in CRSwNP patients. The overall rate of frontal sinusotomies was 12.4%, with significantly higher rates in the CRSwNP patients (21.2%). This is consistent with other literature examining frontal sinus revision rates, though previous studies have been limited by short duration of follow up or small sample sizes.12,13 These sinus specific revision rates may help sinus surgeons determine which sinuses to address during primary surgery, particularly for CRSwNP patients.

The final objective of this study was to identify patient factors that may increase the risk of revision surgery. Similar to previous research, a history of asthma, allergy and nasal polyposis were identified as significant determinants of revision surgery.2,3,6,11,14 Additionally, female gender was also found to be a factor that increases the risk of revision surgery. Stein et al. identified gender as a risk factor as well and there is an increasing body of research to suggest that there are gender dependent differences in patients with CRS.3,15,16 A family history of CRS was also identified as a risk for requiring revision surgery. Recently a familial component of CRS has been identified and this data suggests these patients may have a more severe expression of CRS than those without a familial component.9 Another interesting determinant of revision risk was age, where a younger age at primary surgery was found to be protective against revision ESS. This is thought provoking in the context that there is some debate regarding the prognostic value of symptom duration in predicting clinical disease severity, QOL, and/or postoperative outcomes in patients with CRS.14,17 These additional determinants of age at initial surgery and family history of CRS are two novel risks for revision surgery that may help clinicians counsel their patients in the future.

It is important to consider these results in the context of the limits of this study. The ambulatory care database used for this study was developed in 1996. It is likely there are some patients who have had ESS prior to the development of the database. In this case, we may be underestimating revision rates. Additionally, this study does involve a database review that is largely dependent on ICD coding, which is inherently challenging. However, the cohort under review has previously been validated through chart review with a high sensitivity and specificity for CRS, which strengthens the accuracy and findings of this study.9 The Utah Population Database captures all encounters in Utah, which reduces potential attrition from migration throughout the state and to different physicians, but cannot account for emigration. In spite of these limitations, the large sample size, validated cohort, prolonged duration of follow up and granularity of data supports the findings of this study, which add novel findings to our field.

Conclusions

The long-term revision rate for ESS exceeds 15% and the time between revision surgeries decreased with each additional surgery being performed. Unique patient factors increased the risk of requiring revision ESS, such as a history of asthma, allergy, nasal polyps, family history of CRS and older age at initial surgery. Sinus specific revision rates have also been defined and show significantly higher rates of revision in CRSwNP patients. Frontal sinuses have the highest rates of revision of all the individual sinuses. A better understanding of the natural surgical history of CRS may help physicians select and counsel patients with CRS undergoing ESS and drive future research into the causes of these variations.

Acknowledgements:

We thank the Pedigree and Population Resource of the Huntsman Cancer Institute, University of Utah (funded in part by the Huntsman Cancer Foundation) for its role in the ongoing collection, maintenance and support of the Utah Population Database (UPDB). We also acknowledge partial support for the UPDB through grant P30 CA2014 from the National Cancer Institute, University of Utah and from the University of Utah’s Program in Personalized Health and Center for Clinical and Translational Science (NIH Clinical and Translational Science award 1UL1TR002538). Research was supported by the NCRR grant, “Sharing Statewide Health Data for Genetic Research” (R01 RR021746, G. Mineau, PI) with additional support from the Utah State Department of Health and the University of Utah.

Footnotes

Potential Conflict(s) of Interest:

Kristine A. Smith: None

Gretchen Oakley: None

Huong Meeks: None

Karen Curtin: None

Richard R. Orlandi: Consultant for Medtronic, Lyra Therapeutics, and BioInspire

Jeremiah A. Alt: Consultant for Medtronic, Spirox, Optinose and GlycoMira Therapeutics

References

- 1.Bhattacharyya N Ambulatory sinus and nasal surgery in the United States: demographics and perioperative outcomes. Laryngoscope. 2010;120(3):635–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hopkins C, Slack R, Lund V, Brown P, Copley L, Browne J. Long-term outcomes from the English national comparative audit of surgery for nasal polyposis and chronic rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope. 2009;119(12):2459–2465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stein NR, Jafari A, DeConde AS. Revision rates and time to revision following endoscopic sinus surgery: A large database analysis. Laryngoscope. 2018;128(1):31–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miglani A, Divekar RD, Azar A, Rank MA, Lal D. Revision endoscopic sinus surgery rates by chronic rhinosinusitis subtype. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dalziel K, Stein K, Round A, Garside R, Royle P. Endoscopic sinus surgery for the excision of nasal polyps: A systematic review of safety and effectiveness. Am J Rhinol. 2006;20(5):506–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mendelsohn D, Jeremic G, Wright ED, Rotenberg BW. Revision rates after endoscopic sinus surgery: a recurrence analysis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2011;120(3):162–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Philpott C, Hopkins C, Erskine S, et al. The burden of revision sinonasal surgery in the UK-data from the Chronic Rhinosinusitis Epidemiology Study (CRES): a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2015;5(4):e006680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith KR. Utah Population Database. 2018; https://healthcare.utah.edu/huntsmancancerinstitute/research/updb/acknowledging-updb.php Accessed June 23, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oakley GM, Curtin K, Orb Q, Schaefer C, Orlandi RR, Alt JA. Familial risk of chronic rhinosinusitis with and without nasal polyposis: genetics or environment. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2015;5(4):276–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rudmik L, Holy CE, Smith TL. Geographic variation of endoscopic sinus surgery in the United States. Laryngoscope. 2015;125(8):1772–1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu AW, Ting JY, Platt MP, Tierney HT, Metson R. Factors affecting time to revision sinus surgery for nasal polyps: a 25-year experience. Laryngoscope. 2014;124(1):29–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chiu AG, Vaughan WC. Revision endoscopic frontal sinus surgery with surgical navigation. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130(3):312–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naidoo Y, Bassiouni A, Keen M, Wormald PJ. Risk factors and outcomes for primary, revision, and modified Lothrop (Draf III) frontal sinus surgery. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2013;3(5):412–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hopkins C, Rimmer J, Lund VJ. Does time to endoscopic sinus surgery impact outcomes in Chronic Rhinosinusitis? Prospective findings from the National Comparative Audit of Surgery for Nasal Polyposis and Chronic Rhinosinusitis. Rhinology. 2015;53(1):10–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lal D, Golisch KB, Elwell ZA, Divekar RD, Rank MA, Chang YH. Gender-specific analysis of outcomes from endoscopic sinus surgery for chronic rhinosinusitis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2016;6(9):896–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lal D, Rounds AB, Divekar R. Gender-specific differences in chronic rhinosinusitis patients electing endoscopic sinus surgery. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2016;6(3):278–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alt J, Orlandi R, Mace J, Soler ZM, Smith TL. Does delaying endoscopic sinus surgery adversely impact quality-of-life outcomes? Laryngoscope. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]