Abstract

Objectives

The Strong Black Woman (SBW) ideal, which emphasizes self-reliance and strength, is considered an influential cultural image for many Black women. Research on how the SBW ideal may be reflected in maternal socialization is largely theoretical or qualitative. Methods: Guided by cultural models of parenting, we tested for racial/ethnic differences in the importance and meaning of SBW-related attributes among 194 low-income, Black (22%), White (20%), and Latina (57%) families. Mothers (M = 41.6 years) and daughters (M = 15.4 years) completed semi-structured interviews, q-sort tasks, and self-report measures. Group differences were examined with ANCOVA, logistic regression, and multi-group path models.

Results

Black adolescents were not described by mothers or adolescents as possessing more SBW-related attributes (e.g., strong-willed, independent, assertive) compared to adolescents of other racial/ethnic groups; however, tests of moderation indicate group differences in how mothers perceived these attributes. Black adolescents with high SBW-related attributes were viewed by their mothers as showing leadership, whereas White and Latina adolescents with these attributes were viewed by mothers as having externalizing problems. Black mothers also rated these attributes as more important for young adult women to possess compared to other mothers. Finally, Black mothers described self-reliance as the critical developmental task for their daughter more than White and Latina mothers.

Conclusions

Findings suggest attributes consistent with the SBW ideal are valued by Black mothers more than Latina and White mothers from similar communities, and provide empirical support about the potential importance of the SBW ideal in how Black mothers raise their daughters.

Keywords: Strong Black Woman, racial/ethnic differences, parental socialization, adolescent

Most parents strive to raise children who can survive, adapt, and succeed at each stage of development. Parents’ beliefs about what this entails, however, vary based on the broader context in which they reside (Bornstein, 2012). In cultural models of development, these beliefs are presumed to reflect implicit developmental agendas, or culturally shared expectations about what children should learn and do at specific points in their development and what attributes they need for adulthood (Super & Harkness, 1986; Weisner, 2002). In the United States, children’s developmental contexts are shaped by social position factors, including race, ethnicity, class, and gender (Tamis-Lemonda & McFadden, 2010), which may result in differences in parents’ developmental agendas (e.g. Harding, Hughes, & Way, 2016; Richman & Mandara, 2013; Suizzo, 2007).

In this study, we examine whether attributes consistent with the Strong Black Woman (SBW), an influential image in Black culture, are reflected in the developmental agendas of Black mothers of adolescent daughters compared to White and Latina mothers from the same communities. We focus specifically on mothers and adolescent daughters because racial/ethnic identity and gender interact to create a unique experience (Else-Quest & Hyde, 2016), and this intersectionality is evident in parental socialization (Chuang & Tamis-LeMonda, 2009; Varner & Mandara, 2013). Moreover, changes during adolescence, including physical maturation, enhanced autonomy-seeking, and awareness of approaching adulthood, can invoke parents’ culturally rooted values about what children need to survive and succeed (Greenfield, Keller, Fuligni, & Maynard, 2003).

The Strong Black Woman Ideal

Among African-Americans, the “Strong Black Woman” (SBW) is frequently cited as an influential gender image (e.g., Beauboeuf-Lafontant, 2007; Hill Collins, 2009; Woods-Giscombé, 2010). The SBW image has been described with different terms; however, two key attributes are consistent across multiple theoretical papers and qualitative studies (e.g., Abrams, Maxwell, Pope, & Belgrave, 2014; Woods-Giscombé, 2010). The first of these attributes is self-reliance. Throughout American history, enslavement, separation from male partners, and limited access to resources has required Black women to take on multiple roles in order to provide for themselves and their families (Beauboeuf-Lafontant, 2007; Woods-Giscombé, 2010). In contemporary society, the disproportionate rate of incarceration, unemployment, and the shorter life span of Black men means that Black women often need to maintain financial independence (Abrams et al., 2014; West, Donovan, & Daniel, 2016). In light of historical and current contextual demands, many Black women feel as though they cannot rely on others to provide for them, and that they must financially support family members, even with limited means (Beauboeuf-Lafontant, 2009; Woods-Giscombé, 2010).

A second main attribute in the SBW image is emotional strength, particularly in the form of resistance to vulnerability and belief in one’s self (Nelson, Cardemil, & Adeoye, 2016). Many Black women describe putting on a figurative mask to cover up thoughts and emotions that would make them appear weak (Beauboeuf-Lafontant, 2009). In addition, most Black women expect to have experiences in which they are devalued by being rendered invisible or through overt hostility; thus, they must possess enough self-confidence and assertiveness to overcome these situations and advocate for themselves in the face of barriers (Abrams et al., 2014; Nelson et al., 2016).

In recent years, there has been growing awareness that the SBW image can have mental health costs to Black women and contribute to stereotypes (e.g., Beauboeuf-Lafontant, 2009; Donovan & West, 2015). For example, many Black women believe that they are solely responsible for advocating for their and their families’ needs and rights, requiring them to be assertive, outspoken, and in positions of leadership within the family and in the community (Abrams et al., 2014). While these attributes are understood as a positive form of leadership, they may be viewed by others as being overly assertive or aggressive (Ridgeway, 2001). For Black women in particular, being assertive and strong-willed could be misperceived as anger, aggression, or hostility, as these characteristics stand in contrast to norms of women as submissive and nurturing (Ashley, 2014).

Socialization of SBW attributes within the family

The SBW image is perpetuated via multiple socialization agents, including social institutions, media, and family, but mothers may be particularly important. When asked about child-rearing goals, Black mothers emphasize education, self-respect, and the hope that their daughters will be strong and self-reliant (Sharp & Ispa, 2009). In addition to teaching their daughters to be functioning citizens in American culture, they also must teach them how to deal with racism and sexism (Belgrave, 2009). Black female family members report that socializing girls to be strong, assertive, and independent is a form of protection for a life likely to be impacted by hardships (Donovan & Williams, 2002; Mandara, Murray, & Joyner, 2005). Black parents may also push their daughters to pursue education and employment so that they can provide for their families and communities because they expect racial discrimination will have a bigger impact on sons (Varner & Mandara, 2013).

Fortitude is also emphasized to Black girls by family members. For example, Black mothers often incorporate messages of emotional strength and promotion of self-esteem while trying to teach their daughters developmental lessons, such as sexual decision-making (Shambley-Ebron, Dole & Karikari, 2016). Black women cite memories of watching their mothers and grandmothers deal with tragic situations without crying as ways they learned to value emotional strength (Woods-Giscombé, 2010). Similarly, Black adolescent females report admiring their mothers and grandmothers for their independence and willingness to fight for themselves and their families (Kerrigan et al., 2007). Together, these studies suggest that adolescents and young women may learn about the importance of self-reliance, strength, and self-confidence within the family, and primarily from their mothers or other female members.

Current Study

To date, the vast majority of research on the SBW image has been qualitative or included only Black women as participants. The extent to which attributes such as self-reliance or strength are particularly relevant to Black women compared to women from other racial/ethnic groups is unknown. Mothers from all racial/ethnic groups in the United States report some similar values, such as independence and educational achievement, in socializing their children (Tamis-Lemonda & McFadden, 2010). However, as highlighted above, Black mothers may have distinct values in raising their daughters because of the historical and current circumstances of African-Americans in the United States. Indeed, sociocultural scholars have described the SBW image as an intentional contrast to prevailing images of White women as emotional and in need of protection (e.g., Beauboeuf-Lafontant, 2003). In contrast to self-reliance, White, middle-class mothers often focus on self-expression and individualism as important socialization goals for their children (Tamis-Lemonda & McFadden, 2010). Among Latina mothers, marianismo, or the importance of proper behavior, nurturance, and respecting authority, is often emphasized in socializing their daughters (Castillo, Perez, Castillo, & Ghosheh, 2010). Thus, there are reasons to expect that attributes such as self-reliance, strength, and fortitude may be emphasized more by Black mothers compared to mothers from other racial/ethnic groups. On the other hand, because the SBW image is rooted in Black women’s marginalization due to racism, sexism, and poverty, other groups who experience marginalization may share similar values. All women are impacted by sexism to some degree; poor women, regardless of race or ethnicity, face economic hardships and uncertainty about financial support from others; and women of color from various backgrounds are subject to racism and discrimination. Moreover, regardless of race, parents who live in high risk communities may emphasize self-reliance and strength because of contextual threats (Hill, Murry, & Anderson, 2005). Despite a growing literature on the SBW image, surprisingly few studies have empirically tested whether there are racial/ethnic group differences in the importance or meaning of attributes associated with this image.

The goal of this study was to empirically test whether measures of the developmental agendas of Black mothers incorporate attributes consistent with the SBW image more than White and Latina mothers from similar socioeconomic backgrounds. In previous cross-cultural research, parents’ implicit developmental agendas have been measured by examining how parents describe their child, the meaning they put on specific behaviors, what they see as the most important aspects of each developmental period, and their image of an adaptive adult (e.g., Harding et al., 2016; Harkness & Super, 1992, Rosenthal & Roer-Strier, 2001; Suizzo, 2007). Drawing from these studies, we tested for racial/ethnic group differences in these four areas by asking:

Are Black adolescent girls described as possessing attributes (e.g., strong-willed, independent, ambitious, and assertive) consistent with the SBW ideal more than White and Latina adolescents based on maternal and adolescent report?

Do Black mothers view these attributes as more important for young adult women to possess than White and Latina mothers?

Are these attributes in adolescent daughters seen in a more positive way by Black mothers? Specifically, are these attributes differentially associated with ratings of leadership (positive) or aggressive (negative) behaviors by race/ethnicity?

Do Black mothers focus on the development of self-reliance and independence in their view of the critical tasks of adolescence compared to White and Latina mothers?

To address the first question, mothers and adolescents completed q-sort tasks describing the adolescent. To address the second question, mothers completed a second q-sort task rating the attributes they believed are most important for a young adult woman to possess to succeed in today’s world. To address the third question, we tested whether the relation between mothers’ ratings of strength and independence attributes (e.g., strong-willed, independent, assertive, ambitious; subsequently called SIA) in their daughters and their reports of leadership and externalizing behaviors was moderated by race/ethnicity. To address the fourth question, we used thematic analysis of mothers’ responses to an open-ended question about the most important tasks of adolescent development from a five question parental ethnotheories interview (Harkness & Super, 1992). We hypothesized that compared to White and Latina mothers, Black mothers would: a) give higher ratings to SIA in descriptions of the adolescent, b) judge SIA as a more important developmental outcome for adult women to possess, c) associate high SIA in their daughter with behaviors associated with leadership and rather than aggressive behaviors, and d) see self-reliance and independence as central tasks of the adolescent developmental period.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

Study participants included 194 adolescent girls and their mothers residing in a midsized, low-income city in the Northeast US (population 72,939). In 96% of dyads, the caretaker was the biological mother. In other cases, the primary caretaker was a biological relative (aunt, grandmother) or step-mother. Families were participating in a larger NIH-funded study aimed at understanding the cultural and relational context of health disparities among adolescent girls. All girls entering 9th through 11th grade within the city who were not pregnant or had children, were living full time with their mother/female caregiver, and could complete the interview in English, Spanish, or Polish were eligible for participation. The average age of participants was 15.4 years (SD = 1.05; Range = 13-17). Caregivers ranged from 22.83 to 66.42 years (M = 41.6, SD = 7.95). Fifty-eight percent of participants identified as Latina (primarily Puerto Rican), 22% as African American/Black, and 20% as non-Hispanic, White. Thirty percent of homes included both biological parents at the time of participation. Forty-two percent of women had become mothers by the age of 18. Educationally, 21% of mothers had not completed high school, 68% had a high school degree, and 11% had a bachelor’s degree. The majority of adolescents (87%) qualified for free or reduced lunch.

Participants were recruited from city schools, community centers, health centers, YWCA, local media outlets, and word-of-mouth. Interviews were conducted in English (80%) and Spanish (20%) based on participant preference. All measures were translated and backtranslated and then piloted with local residents in an iterative process, following guidelines of the World Health Organization (see www.who.int/substance_abuse/research_tools/translation/en/). Mothers and daughters participated separately in face-to-face, semi-structured interviews, which were audiotaped and later transcribed verbatim. Spanish interviews were translated and transcribed by bilingual, native Spanish speakers with each translated interview reviewed by a second reader. After the audiorecorded interview, participants completed the q-sort task, and then completed survey measures via Audio Computer Assisted Survey Instruments (ACASI) programmed in their preferred language. Interviews took approximately 2.5 hours, and participants were paid $40 each for their time. All procedures were approved by the [omitted for blind review] Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Demographics

Mothers provided detailed demographic information on age, race/ethnicity, country of origin and immigration history, marital status and family structure, childbearing history, and various indicators of socioeconomic status (SES). Although all families would be considered ‘low-income’ based on definitions by the National Center for Children in Poverty (see http://www.nccp.org/profiles/US_profile_6.html), an SES risk composite was computed to capture variations in economic disadvantage within this group. The SES risk composite was a count of three indicators: no HS degree, living in public housing, and receipt of free (as opposed to reduced or full cost) lunch. For race/ethnicity classification, mothers were given a list of all racial/ethnic groups listed in the census and were allowed to choose all groups with which they identified1.

SIA attributes

Participants completed q-sort tasks sorting cards describing 19 traits. Items were drawn from Antill, Russel, Goodnow, and Cotton’s (1993) 12-item Trait Questionnaire of agentic and instrumental traits (i.e., strong-willed, ambitious, assertive, competitive, independent, adventurous) or communal and expressive traits (i.e., caring, gentle, helpful, respectful, generous). This questionnaire reliably measures these two domains in adolescents (e.g., McHale et al., 2009). The remaining words were selected by the research team drawing from existing studies of parental descriptions of children (e.g., Ng et al., 2012) to select commonly used words with less clearly agentic or communal meaning (e.g., smart, athletic, truthful, responsible). On each card, definitions were written directly under the word (“This is the sort of person who….”) consistent with the Antill et al. (1993) measure. To pilot the measure, eight undergraduate students first matched words with their definition and then chose five words that best reflect agentic/independent characteristics and five words that best reflect communal/social characteristics after being given lay definitions of these concepts. Responses indicated that words and definitions were described clearly (over 95% correct matching), and that the words from the Antill et al. (1993) measure reflecting agentic traits were viewed that way (each of the target words was selected correctly by at least six of the eight respondents; none of the other words was selected more than three times). The same process was conducted with three mothers from the same sociodemographic background as study participants with similar accuracy, except for the word adventurous. We did not include adventurous in subsequent composites.

Adolescents completed one sorting task based on traits they believed were least/most like them. Mothers completed two sorts. First, they sorted cards to describe their daughter. Then, they did a second sort to reflect their “image of an adaptive adult”, following Roer-Strier and Rosenthal (2001). Specifically, mothers were told to imagine a young woman growing up in today’s world and then instructed to sort the cards based on how important they believed each of the traits were for that woman “to make a good life for herself and to be okay and get by in the world she lives in, based on your own experiences and opinions.” In all sorts, cards were placed on a large poster board with a forced-choice, normal distribution. The distribution ranged from 1 (least important) to 7 (most important), allowing 1 word to be placed in the most/least important spots, 2 words in the next spots (values 2 and 6 on the 1-7 scale), 4 words in the next spots (3 and 5 on the 1-7 scale) and 5 words in the middle spot (value 4 on the 1-7 scale). Mothers were allowed to change the position of any card during the process and again at the end. The mean placement values for the 5 agentic words were computed for daughter’s self-description, mother’s description of daughter, and mother’s description of important traits for an adult woman. Because a forced distribution q-sort ranking task results in ipsative data, Cronbach’s alpha is not an appropriate indicator of reliability. Following recommendations by Maydeu-Olivares and Böckenholt (2005), we used confirmatory factor analysis for ranked data to calculate composite reliabilities. Values were .56 to .60 for the three measures; values above .5 suggest adequate reliability (Bacon, Sauer & Young, 1995). Higher scores on the SIA composite reflect higher placement of the 5 agentic words.

Emphasis of adolescent developmental period

Mothers participated in a 5-question parental ethnotheories interview designed by Harkness & Super (1992) to assess differences in culturally rooted parental beliefs about child development. Responses were audiorecorded and transcribed verbatim. Mothers’ responses about what they viewed as the most important part of their daughter’s development at her current age were coded for this study (Now that your daughter is __ years old and an adolescent, what do you think she needs most at this age? What do you see as the most important part of her development right now?). Four independent undergraduate research assistants blind to research hypotheses and participant race/ethnicity coded responses for 6 developmentally relevant themes: 1) social (e.g., developing friendships, healthy romantic relationships, staying connected to family); 2) cognitive/academic achievement (e.g., do well in school, identify and develop career interests); 3) physical (e.g., be healthy, make good sexual decisions); 4) emotional (e.g., be happy, learn to manage emotions); 5) identity development (e.g., understand cultural, sexual or religious identity); 6) self-reliance and independence (e.g., taking on increased adult responsibilities; managing daily needs and requirements without adults, belief in her ability to manage challenges independently). Responses could receive multiple codes. Only the self-reliance/independence code (kappa = .81) is of interest in the current study. An example of a maternal response including this theme is: “How to take care of herself, as a young adult and when she’s not around me, when I can’t protect her from things, she needs to know how to think things though and control her situations she’s in and stand up for herself and things like that.” (PID 66).

Adolescent adjustment

Mothers completed domains of the parent report Behavioral Assessment System for Children-2 (BASC-2; Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2004) and BASC Behavioral and Emotional Screening System (BASC-BESS; Kamphaus & Reynolds, 2007). The BASC instruments are both widely used, well-validated measures in which the frequency of specific behaviors in the last six months is reported on a 0-3 scale. Two subdomains were used in the present analysis: the leadership subscale from the BASC-2 (9 items, α = .77) to reflect adaptive or positive behaviors, such as “joins clubs or social groups” and “is a ‘self-starter,’” and the externalizing items from the BASC-BESS (11 items, α = .83) which targets aggressive and defiant behaviors, such as “argues” and “defies people in authority”. These two domains were selected because the SIA included in this study (e.g., assertive, strong willed) may be viewed as signs of leadership or aggression.

Data analytic plan

ANCOVAs were used to test racial/ethnic differences in endorsing SIA in the q-sorts. A nested path model was run in Amos 19 to examine whether relations between SIA and leadership or externalizing behaviors differed by race/ethnicity using chi-square differentials and critical ratio z-tests to test for group differences in parameter estimates. Logistic regression was used to test for racial/ethnic differences in the likelihood of focusing on independence and self-reliance as critical aspects of the adolescent developmental period in mothers’ open-ended responses.

Results

Demographic information by race/ethnicity is presented in Table 1. As shown, there were racial/ethnic group differences in factors comprising the SES risk factor (no high school degree, living in public housing, receipt of free lunch). As a result, White women had lower scores on the SES risk composite than Black or Latina mothers, χ2(df = 6, N = 194) = 34.5, p < .001. Latina mothers were also significantly younger than other mothers, but there was no difference in marital status. SES risk was controlled for in subsequent analysis; maternal age was not significantly related to any of the outcome variables used in this study and was therefore not included as a control variable.

Table 1.

Demographic variables by racial/ethnic group (N = 194)

| Variable | Total (n = 194) |

Black (n = 43) |

Latina (n = 113) |

White (n = 38) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daughter Age Mean (SD) |

15.4 (1.05) |

15.32 (.93) |

15.42 (1.10) |

15.45 (1.06) |

F(2,191) = .18, p = .84 |

| Mother Age Mean (SD) |

41.62 (7.95) |

44.04 (7.70) |

39.94 (7.73) |

43.87 (7.80) |

F(2,191) = 6.39, p = .002 |

| Live with biological mother | 96% | 93% | 96% | 97% | χ2(2, N = 192) = 1.16, p =.56 |

| Live with biological father | 30% | 30% | 27% | 37% | χ2(2, N = 194) = 1.2, p =.55 |

| Maternal education level | χ2(4, N = 194) = 27.05, p < .001 | ||||

| Less than HS | 21% | 19% | 29% | 0% | |

| HS degree | 68% | 61% | 67% | 77% | |

| 2 or 4 year college degree | 11% | 18% | 5% | 23% | |

| Section 8 housing | 29% | 40% | 35% | 6% | χ2(2, N = 188) = 16.73, p < .001 |

| School lunch | χ2(4, N = 186) = 32.2, p < .001 | ||||

| Free | 65% | 73% | 74% | 30% | |

| Reduced | 22% | 17% | 19% | 32% | |

| Full | 13% | 10% | 7% | 38% |

The first set of analyses examined racial/ethnic differences in mothers’ and daughters’ q-sort responses about how descriptive SIA were of the daughter, and how much importance mothers put on adult women possessing SIA. Mean scores and results from ANCOVAs are presented in Table 2. As shown, Black mothers did not rate their daughters higher on these traits compared to other mothers, nor did Black adolescents rate their selves higher compared to other adolescents. Significant racial/ethnic group differences were evident in mothers’ ratings of how important they believed these traits are for a woman growing up today to possess, F(2,184) = 3.63, p <. 05. In post-hoc LSD comparisons, Black mothers rated SIA as more important compared to both White (Mean difference = .45, p < .05, Cohen’s d = .43) and Latina (Mean difference= .32, p < .05, Cohen’s d = .40) mothers. Across the sample, mothers tended to rate the importance of women having SIA higher than how they rated their daughters on these attributes currently (Mean score ratings of 4.25 versus 3.86 on a 1-7 scale; paired sample t(188) = 6.10, p < .001). As shown in Table 2, the discrepancy between what daughters currently possessed from their mothers’ perspective versus what women were perceived to need was most pronounced for Black mothers.

Table 2.

Racial/ethnic group differences in q-sort ratings of Strength and Independence Attributes

| Race/Ethnicity | Mother’s description of daughter Mean (SD) |

Adolescent self-description Mean (SD) |

Mother’s report of important traits for a woman Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Black n = 43 |

3.90 (.63) | 3.75 (.65) | 4.51 (.88)a |

| White n = 38 |

3.79 (.62) | 3.63 (.76) | 4.16 (.76)b |

| Latina n = 113 |

3.88 (.64) | 3.83 (.65) | 4.18 (.75)b |

| F, η2 | F(2,190) = .02, p = .98, η2= .00 | F(2,190) = .82, p = .44, η2 = .01 | F(2,184) = 3.63, p = .03, η2= .04 |

Note. Values with different subscripts are statistically different in post hoc testing. Socioeconomic risk was controlled in analyses.

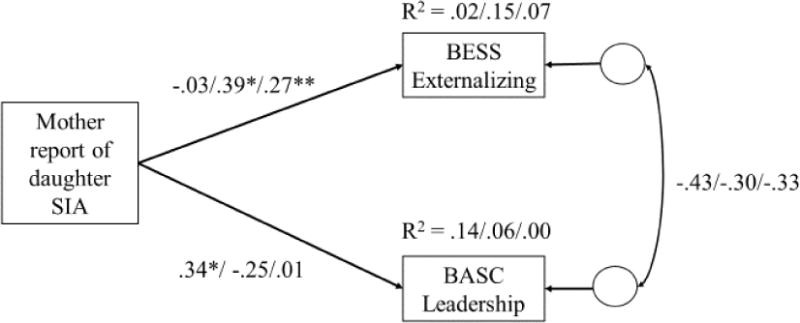

Next, we examined whether mothers’ perceptions of SIA in daughters has a more favorable meaning to Black mothers. The path model presented in Figure 1 was tested as a nested model with the two paths of interest (SIA ➔ leadership; SIA ➔ externalizing) freely estimated in one model and constrained to be equal across race/ethnicity in the second model. SES risk was included as a covariate. There were no differences in mean ratings of externalizing symptoms, F(2, 188) = 1.06, p = .35, or leadership, F(2, 188) = .12, p = .88, by race/ethnicity. However, nested model comparison indicated that the relation between SIA and these two behavioral domains differed by race. The overall model with paths of interest freely estimated and the SES path equal provided a good fit to the data (χ2 = 2.65, df = 4, p = .62, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = .000). The model with parameters from SIA constrained significantly worsened fit (differential χ2 = 10.30, df = 4, p < .05), indicating these paths varied by race. For Black mothers, high SIA in their daughter were positively related to leadership behaviors, B = .31, SE = .13, p = .02, but unrelated to externalizing symptoms, B = −.03, SE = .07, p = .67. For White and Latina mothers, there was no relationship between SIA and leadership, White B = −.21, SE = .14, p = .14; Latina B = .02, SE = .08, p = .84, but daughters viewed as having more SIA qualities were seen as having more externalizing problems, White B = .28, SE = .11, p = .02; Latina B = .20, SE = .07, p = .005. As reported in Figure 1, path estimates for Black women were significantly different than those of White and Latina women in follow-up critical ratio z-tests for both paths.

Figure 1.

Results from multigroup nested model of the relation between mother’s report of daughters’ strength and independence attributes (SIA) to mother report of externalizing and leadership behaviors.

Note. Standardized regression weights are listed in order of race, Black/White/Latina and SES risk was added as a covariate. The chi-square differential test indicated the model differed by race (differential χ2 = 10.30, df=4, p<.05). In follow-up critical ratio z tests, the path estimate from SIA to externalizing was significantly lower in Black mothers compared to White (z=−2.75, p<.05) and Latina (z=−1.89, p<.05) mothers. The path estimate from SIA to leadership was significantly higher in Black mothers compared to White (z=2.25, p<.05) and Latina (z=2.15, p<.05) mothers. SIA – Strength and Independence Attributes, BESS – Behavioral and Emotional Screening System, BASC – Behavioral Assessment System for Children.

* p<.05 **p<.01

Finally, logistic regression was used to examine whether Black mothers were more likely to emphasize self-reliance and independence in describing what the most important developmental task for their adolescent daughters. Overall, 35% of mothers incorporated self-reliance and independence themes in their responses to this question. This rate varied by race/ethnicity, χ2(df = 2, N = 189) = 12.16, p < .01, with 55.8% of Black mothers, 36.9% of White mothers, and 25.9% of Latina mothers incorporating this theme. In logistic regression controlling for SES risk, the model was significant, Model χ2(df = 3, N = 189) = 11.93, p < .01, due to the significant race/ethnicity categorical variable, Wald = 11.63, p < .001; there was no relation with SES risk, B = −.03, SE = .18, p = .84. In categorical contrasts, Black mothers were more likely to incorporate self-reliance themes than White (AOR = 2.09, 95% CI = .84-5.4, p = .13) or Latina (AOR = 3.62, 95% CI = 1.73-7.50, p < .001) mothers, although only the contrast between Black and Latina mothers was statistically significant, likely due to the smaller White sample.

Discussion

The SBW image is frequently cited as an influential force in the lives of Black women (Woods-Giscombé, 2010), and qualitative studies suggest this image plays a role in how parents socialize Black daughters (e.g., Beauboeuf-Lafontant, 2009). To date, however, no empirical studies have tested whether characteristics emphasized in the SBW image are more salient or valued among Black mothers compared to mothers of other racial/ethnic groups, particularly those from similar socioeconomic backgrounds. In this study, we drew from cultural models of parenting to examine whether Black mothers were more likely than Latina or White mothers from the same community to: a) describe their daughter with SIA; b) view SIA as more important for women to possess as adults; c) see high levels of SIA in their daughter more positively; and d) put more importance on their daughter developing self-reliance and independence during adolescence. Racial/ethnic group differences in these areas support hypotheses about the relevance of SIA for Black families in the United States.

In cross-cultural research, the words parents use to describe their child have been viewed as a reflection of the underlying socialization priorities of that cultural group (e.g., Harkness & Super, 1992). Thus, we hypothesized that SIA would be viewed as more descriptive of adolescent girls in Black families compared to White and Latina families. Our findings did not support this hypothesis: there were no racial/ethnic group differences in mean ratings of SIA given by mothers or daughters in describing the adolescent. If Black mothers place greater value on these attributes, we might expect group differences to be evident by the teenage years; this was not the case. Interestingly, no known studies have examined whether Black women actually report having more of these attributes relative to the self-descriptions of women from other racial/ethnic groups. Rather, existing studies on Black women’s endorsement of the SBW image have focused primarily on whether they believe that they are expected to possess these attributes (e.g., Donovan & West, 2015).

Although Black mothers did not describe their daughters as showing more SIA, our findings suggest they may view these attributes in their teenage daughters more favorably than mothers of other racial/ethnic groups. For Black mothers, daughters who were described as having more SIA were seen as demonstrating more leadership behaviors. In contrast, White and Latina mothers who described their daughters with more SIA described them as more aggressive. There is some evidence that African-Americans tend to report more liberal or gender-neutral role orientations than other groups, at least for women (Hill, et al., 2005). Characteristics such as being strong-willed or assertive are less traditionally feminine traits, which could be one reason they were viewed more negatively by White and Latina mothers but not Black mothers.

The differential associations between SIA and externalizing problems have implications for clinicians who work with diverse adolescents. In White and Latina families, but not Black families, adolescent girls being assertive, independent, and strong-willed may have more negative connotations. As a result, White or Latina clinicians or teachers may misinterpret Black mothers encouraging SIA in their daughters as indication that they are encouraging aggressive behaviors, rather than promoting traits deemed important to navigate environmental demands. This difference also could have implications for how items on commonly used clinical behavioral ratings are interpreted. Items such as “argues with others” may be viewed by Black parents in one way (e.g., standing up for oneself), yet seen by teachers or clinicians from other backgrounds as an indicator of acting out. Consistent with this possibility, Miner and Clarke-Stewart (2007) found that teachers (who were predominantly White) rated Black youth as more aggressive than White youth, but that the reverse pattern was found in maternal ratings of the same children. Teachers and clinicians should consider how their interpretations of behavior of Black girls may differ from their parents when considering cultural and historical context.

While we have focused on findings for Black families, the significant association between SIA and externalizing behaviors for White and Latina mothers is also noteworthy. If low-income Latina and White mothers value deference to authority or kindness toward others in their adolescents (e.g. Harding et al., 2016), then being highly assertive or independent in regards to relationships may have more negative connotations. In this context, these attributes may be associated with behaviors such as arguing, talking back, or other forms of interpersonal aggression. However, with only limited research exploring racial/ethnic differences in socialization goals and values of low-income mothers of adolescents in the U.S., these findings need to be replicated.

Parents’ image of the “ideal adaptive adult”, assumed to reflect desired long-term socialization goals, has also been used as a measure of parents’ implicit developmental agendas (e.g., Roer-Strier & Rosenthal, 2001). To assess variations in this image, mothers in this study were asked to imagine a young woman growing up in today’s world, and rank the attributes they thought were most important for that woman to possess in order to manage and succeed. Black mothers ranked attributes such as independent, strong-willed, and assertive as more important traits than White and Latina mothers, supporting our hypothesis that Black mothers’ long-term developmental goals would include aspects of the SBW-ideal.

Across the sample, mothers tended to give significantly higher ratings to SIA traits when describing what a woman needs (ideal) compared to when describing their daughter currently (actual). Thus, mothers from all three groups may feel pressure to help their daughter develop these traits during the years of adolescence, given that most parents expect independence to increase during adolescence. The ideal versus actual difference, however, was most evident among Black mothers because they tended to put greater importance on SIA for an adult woman. This may be one reason Black mothers were more likely to emphasize developing independence and self-reliance as the critical developmental task for their daughter currently. If adolescence is the time when Black mothers focus on socializing their daughters toward SIA, these girls may be ‘en route’ to developing more of these attributes. This process of developing these attributes may be especially concerning for Black mothers, as independence in some areas (e.g. increased importance of peers) may occur faster than in others (e.g. ability to manage finances). However, it is possible that this discrepancy reflects the potentially unachievable nature of the SBW image. Qualitative studies indicate that while Black women may value SBW traits, they often find it difficult to live up to this ideal (Nelson et al., 2016). The discrepancy between ideal and actual may result in distress for both adolescents and mothers. For example, Black parents report that they place higher academic and behavioral demands on their daughters compared to their sons (Varner & Mandara, 2013). These heightened expectations may promote success, but also be a source of emotional distress for Black adolescents and young adult females (West et al., 2016). Moreover, for Black mothers who believe young women need certain attributes to manage and succeed in the face of racism, sexism, and economic inequity, the extent to which their daughters do not exhibit these attributes could be a unique source of parental stress.

Mothers were also asked what they considered the most important developmental task at their daughter’s age. The racial/ethnic group differences in the themes present in maternal responses support our hypotheses about the SBW ideal. Compared to White or Latina mothers, Black mothers emphasized their daughters developing self-reliance, independence, and a belief in her own self-efficacy, with the majority of Black mothers giving a response with this theme. At each stage of development, parental socialization generally focuses on attributes or skills parents deem most important for their child in order to negotiate current and future environmental demands. For Black mothers, the development of self-reliance may be viewed as important preparation for adulthood in light of the longstanding economic disparities associated with race and gender in the United States (Shambley-Ebron et al., 2016). This emphasis may also reflect a perceived need for self-protection and self-advocacy. Compared to mothers of other racial/ethnic groups, Black mothers give more socialization messages that encourage caution when dealing with other people (Wray-Lake, Flanagan & Maggs, 2012). If the social world is seen as holding more potential danger, ensuring your daughter can take care of herself takes on increased importance. As one Black mother in this study responded:

“Well with everything going on in this world, and what I see and learn on TV and everything that’s going on around me, I want her to be open, her mind to open to her surroundings and her environment. To know how to protect herself; know how to help her brother and sister…So I try to tell her don’t be afraid to be outspoken, to your friends or whoever, stand up for yourself and your rights…you gotta have that stamina to stand up for yourself because she’s soft-hearted…” (ID# 171)

These messages, even when cautionary, may help promote the well-being of Black adolescent girls. Indeed, Black girls consistently report higher self-esteem than other groups (see Twenge & Crocker, 2002), and perceptions of maternal encouragement of independence and strength has been shown to account for racial differences in girls’ self-esteem (Ridolfo, Chepp, & Milkie, 2013). Self-esteem may, in turn, act as a psychological resource for Black females when faced with racism, sexism or other hardships.

Limitations

Several study limitations should be considered. First, the sample size for this study was fairly small; thus, group comparisons may have been underpowered. Similarly, the sample came from a specific geographical area, which has implications for generalizability. The White mothers in this sample were primarily low-income and contained several first- and second-generation immigrants. While there has been a great deal of research on White mothers, most of it has been on middle-class, American-born mothers. Among the Latina mothers, the vast majority was Puerto Rican, and there is considerable within-group heterogeneity among Latinos associated with region of origin. Additionally, our sample came from a predominately low-income community. The importance placed on SBW traits may vary by SES, and may not be as strong in high-SES Black communities (Beauboeuf-Lafontant, 2009). Relatedly, we only examined adolescent daughters in this study. Similar racial/ethnic group differences may exist in parents’ values for adolescent boys. Future research with larger samples, including broader socioeconomic representation within racial/ethnic groups and both genders, is needed.

Measurements are another potential limitation. There are no validated, direct measures of parents’ developmental agendas and no measures of parental socialization toward SBW attributes. We used q-sorts and content analysis of one open-ended question; two strategies that have been widely used in cross-cultural studies of parenting (e.g., Harkness & Super, 1992; Harding et al., 2017). Results may have differed with the use of self-report surveys or with longer interviews that elicit more narrative. While there are validated measures of endorsement of the SBW image (Lewis, 2015; Thomas, Witherspoon, & Speight, 2004), these measures are specific to Black women and thus do not allow for group comparisons. Another measurement limitation is the two domains (leadership and externalizing) we chose to test whether SIA may have a different meaning to mothers based on race and ethnicity. We chose these two because they are both relevant to SBW traits (e.g., assertiveness) and are typically conceived as indicators of positive or negative adjustment. However, these behaviors may have different meanings in terms of how adaptive they are within different sociocultural contexts.

Conclusion

This study examined a cultural image associated with Black women, the SBW, and provided quantitative evidence that attributes related to this image may be embedded in the parental beliefs of Black mothers. Our findings indicate that SBW-related traits may be deemed particularly important and have a more positive meaning for Black mothers of adolescent girls compared to White and Latina mothers. Existing research with Black women suggests that holding the SBW ideal can have psychological benefits and costs for adults (e.g., Beauboeuf-Lafontant, 2007). This study extends previous work on the SBW among adult women to the mother-daughter dyad in order to understand how these values may develop during adolescence. Future research should examine whether maternal beliefs about SBW attributes have a lasting impact on the parent-adolescent relationship or on adolescent mental health.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded with support from the National Institutes of Health (NICHD R21HDO65185) to Stephanie Milan. Several research assistants and community collaborators gave invaluable assistance, particularly Kate Zona, Viana Turcios-Cotto and Jenna Ramirez.

Footnotes

There were five mothers who self-identified in more than one racial/ethnic group. These mothers were categorized based on the racial/ethnic group they designated for their mother/primary guardian (maternal grandmother to adolescent participants) given the purpose of the study. Results did not differ with these women excluded from analysis.

References

- Abrams JA, Maxwell M, Pope M, Belgrave FZ. Carrying the world with the grace of a lady and the grit of a warrior: Deepening our understanding of the “Strong Black Woman” Schema. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2014;38(4):503–518. doi: 10.1177/0361684314541418. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Antill JK, Russell G, Goodnow JJ, Cotton S. Measures of children’s sex typing in middle childhood. Australian Journal of Psychology. 1993;45:25–33. doi: 10.1080/00049539308259115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ashley W. The angry Black woman: The impact of pejorative stereotypes on psychotherapy with Black women. Social Work in Public Health. 2014;29(1):27–34. doi: 10.1080/19371918.2011.619449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacon DR, Sauer PL, Young M. Composite reliability in structural equations modeling. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1995;55(3):394–406. doi: 10.1177/0013164495055003003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beauboeuf-Lafontant T. “You have to show strength”: An exploration of gender, race, and depression. Gender & Society. 2007;21(1):28–51. doi: 10.1177/0891243206294108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beauboeuf-Lafontant T. Behind the Mask of the Strong Black Woman: Voice and the Embodiment of a Costly Performance. Philadelphia: Temple University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Belgrave F. African American Girls: Reframing Perceptions and Changing Experiences. New York: Springer-Verlang; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH. Cultural Approaches to Parenting. Parenting, Science and Practice. 2012;12(2–3):212–221. doi: 10.1080/15295192.2012.683359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo LG, Perez FV, Castillo R, Ghosheh MR. Construction and initial validation of the Marianismo Beliefs Scale. Counselling Psychology Quarterly. 2010;23(2):163–175. doi: 10.1080/09515071003776036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang SS, Tamis-LeMonda C. Gender roles in immigrant families: Parenting views, practices, and child development. Sex Roles. 2009;60(7–8):451–455. doi: 10.1007/s11199-009-9601-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan RA, Williams M. Violence in the lives of Black women: Battered black and blue. Women & Therapy. 2002;25(3–4):95–105. doi: 10.1300/J015v25n03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan RA, West LM. Stress and mental health: Moderating role of the strong black woman stereotype. Journal of Black Psychology. 2015;41(4):384–396. doi: 10.1177/0095798414543014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Else-Quest NM, Hyde JS. Intersectionality in quantitative psychological research: I. Theoretical and epistemological issues. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2016:1–16. doi: 10.1177/0361684316629797. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield PM, Keller H, Fuligni A, Maynard A. Cultural pathways through universal development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2003;54:461–490. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding JF, Hughes DL, Way N. Racial/ethnic differences in mothers’ socialization goals for their adolescents. Cultural Diversity And Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2016;23(2):281–290. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkness S, Super CM. Parental ethnotheories in action. In: Sigel I, McGillicuddy-DeLisi AV, Goodnow JJ, editors. Parental belief systems: The psychological consequences for children. 2nd. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1992. pp. 373–392. [Google Scholar]

- Hill NE, Murry VM, Anderson VD. Sociocultural Contexts of African American Families. In: McLoyd VC, Hill NE, Dodge KA, editors. African American family life: Ecological and cultural diversity. New York: Guilford Press; 2005. pp. 21–44. [Google Scholar]

- Hill Collins P. Black Feminist Thought. New York, NY: Routledge; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kamphaus R, Reynolds C. BASC-2 Behavioral and Emotional Screening System Manual. Circle Pines, MN: Pearson; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kerrigan D, Andrinopoulos K, Johnson R, Parham P, Thomas T, Ellen JM. Staying strong: Gender ideologies among African-American adolescents and the implications for HIV/STI prevention. Journal of Sex Research. 2007;44(2):172–180. doi: 10.1080/00224490701263785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis J. Construction and initial validation of the Gendered Racial Microaggressions Scale for Black Women. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2015;62(2):289–302. doi: 10.1037/cou0000062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandara J, Murray CB, Joyner TN. The impact of fathers’ absence on African American adolescents’ gender role development. Sex Roles. 2005;53(3–4):207–220. doi: 10.1007/s11199-005-5679-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maydeu-Olivares A, Böckenholt U. Structural equation modeling of paired-comparison and ranking data. Psychological Methods. 2005;10(3):285–304. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.10.3.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale SM, Kim J, Dotterer AM, Crouter AC, Booth A. The development of gendered interests and personality qualities from middle childhood through adolescence: A biosocial analysis. Child Development. 2009;80(2):482–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01273.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miner JL, Clarke-Stewart KA. Trajectories of externalizing behavior from age 2 to age 9: Relations with gender, temperament, ethnicity, parenting, and rater. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44(3):771–786. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.3.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Children in Poverty(n.d.) United States demographics of low-income children. Retrieved from: http://www.nccp.org/profiles/US_profile_6.html.

- Nelson T, Cardemil EV, Adeoye CT. Rethinking strength: Black womens’ perceptions of the “Strong Black Woman” role. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2016 doi: 10.1177/0361684316646716. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ng FFY, Tamis-LeMonda CS, Godfrey EB, Hunter CJ, Yoshikawa H. Dynamics of mothers’ goals for children in ethnically diverse populations across the first three years of life. Social Development. 2012;21(4):821–848. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2012.00664.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds C, Kamphaus R. BASC-2: Behavior assessment system for children. 2004 doi: 10.1080/21622965.2021.1929232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richman SB, Mandara J. Do socialization goals explain differences in parental control between Black and White parents? Family Relations. 2013;62(4):625–636. doi: 10.1111/fare.12022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ridgeway CL. Gender, status, and leadership. Journal of Social Issues. 2001;57(4):637–655. doi: 10.1111/0022-4537.00233. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ridolfo H, Chepp V, Milkie M. Race and girls self-evaluations: How mothering matters. Sex Roles. 2013;68:625–636. doi: 10.1007/s11199-013-0259-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roer-Strier D, Rosenthal MK. Socialization in changing cultural contexts: A search for images of the “adaptive adult”. Social Work. 2001;46(3):215–228. doi: 10.1093/sw/46.3.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shambley-Ebron D, Dole D, Karikari A. Cultural preparation for womanhood in urban African American girls. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2016;27(1):25–32. doi: 10.1177/1043659614531792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp EA, Ispa JM. Inner-city single Black mothers’ gender-related childrearing expectations and goals. Sex Roles. 2009;60(9–10):656–668. doi: 10.1007/s11199-008-9567-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suizzo M. Parents’ goals and values for children: Dimensions of independence and interdependence across four U.S. ethnic groups. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2007;38(4):506–530. doi: 10.1177/0022022107302365. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens-Watkins D, Sharma S, Knighton JS, Oser CB, Leukefeld CG. Examining cultural correlates of active coping among African American female trauma survivors. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2014;6(4):328–336. doi: 10.1037/a0034116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suizzo M. Parents’ goals and values for children: Dimensions of independence and interdependence across four U.S. ethnic groups. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2007;38(4):506–530. doi: 10.1177/0022022107302365. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Super CM, Harkness S. The developmental niche: A conceptualization at the interface of child and culture. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 1986;9:545–569. doi: 10.1177/016502548600900409. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tamis-Lemonda CS, McFadden KE. The United States of America. In: MH Bornstein, MH Bornstein., editors. Handbook of Cultural Developmental Science. New York, NY: Psychology Press; 2010. pp. 299–322. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas AJ, Witherspoon KM, Speight SL. Toward the development of the Stereotypic Roles for Black Women Scale. Journal of Black Psychology. 2004;30(3):426–442. doi: 10.1177/0095798404266061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Twenge JM, Crocker J. Race and self-esteem: Meta-analyses comparing Whites, Blacks, Hispanics, Asians, and American Indians and comment on Gray-Little and Hafdahl (2000) Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128(3):371–408. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.128.3.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisner TS. Ecocultural understanding of children’s developmental pathways. Human Development. 2002;45(4):275–281. doi: 10.1159/000064989. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Varner F, Mandara J. Discrimination concerns and expectations as explanations for gendered socialization in African American families. Child Development. 2013;84(3):875–890. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West LM, Donovan RA, Daniel AR. The price of strength: Black college women’s perspectives on the strong black woman stereotype. Women & Therapy. 2016;39:390–412. doi: 10.1080/02703149.2016.1116871. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Woods-Giscombé CL. Superwoman schema: African American women’s views on stress, strength, and health. Qualitative Health Research. 2010;20(5):668–683. doi: 10.1177/1049732310361892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization(n.d.) Process of translation and adaptation of instruments. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/research_tools/translation/en/index.html.

- Wray-Lake L, Flanagan CA, Maggs JL. Socialization in context: Exploring longitudinal correlates of mothers’ value messages of compassion and caution. Developmental Psychology. 2012;48(1):250–256. doi: 10.1037/a0026083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]