Abstract

Objectives:

Asthma may lead to reduced participation in interactive physical play (IPP). Urban youth with asthma are also at risk for behavioral and academic difficulties. Exploring associations between asthma, IPP, and socio-emotional and academic outcomes in children with asthma is important. Study objectives are to: 1) Describe IPP participation among school children with persistent asthma; 2) Determine if IPP varies with asthma severity; 3) Determine independent associations of both asthma severity and IPP with socio-emotional and academic outcomes.

Methods:

We analyzed data from children with persistent asthma enrolled in the SB-TEAM trial (Rochester, NY). Caregiver surveys assessed asthma severity, IPP participation (gym ≥3 days/week, running at recess, sports team participation), socio-emotional, and academic outcomes. Bivariate and regression analyses assessed relationships between variables.

>Results:

Of 324 children in the study (59% Black, 31% Hispanic, mean age 7.9), 53% participated in any IPP at school. Compared to those with mild persistent asthma, fewer children with moderate-severe asthma had no limitation in gym (44% vs 58%,p<.01), and fewer ran at recess (29% vs 42%,p<.01) or engaged in any IPP (48% vs 58%,p=.046). Asthma severity was not associated with socio-emotional or academic outcomes. However, children participating in IPP had better positive peer social and task orientation skills, were less shy/anxious, and more likely to meet academic standards (all p<.05). Results were consistent in multivariable analyses.

Conclusion:

Urban children with moderate-severe asthma partake in less IPP, which is associated with socio-emotional and academic outcomes. Further efforts are needed to optimize asthmatic children’s participation in IPP.

INTRODUCTION

Asthma is the most common chronic disease of childhood, affecting approximately 9% of children in the United States (US),[1] and children of lower socioeconomic status suffer a disproportionate burden of illness.[2–5] In fact, the prevalence of asthma in some urban, impoverished communities is as high as 25%.[6] The morbidity associated with asthma is far reaching for these children. Asthma causes ongoing symptoms, school absenteeism, reduced quality of life, acute healthcare utilization, and limitations in physical activity.[7–11]

Interactive physical play (IPP) is defined as physical activity during which children are engaged in significant and cooperative peer interaction, and the role of interactive play and physical activity in child development has been widely discussed in recent years.[12] Prior studies have shown that activities that foster physical activity and creative aptitude allow for beneficial peer interactions that are positively associated with learning and behavioral outcomes including skills such as language ability, social competence, and positive approaches to learning.[12, 13] However, schools continue to move towards cutting recess and other in-school creative and physical activities to make room for class time.[13, 14] Children living in poverty may be at highest risk of having little to no interactive physical activity due to these cuts in school interactive play time, along with less ready access to safe out-of-school play settings and less time, energy, and resources at home for families to provide active play time.[13] Thus, impoverished children with asthma may be disproportionately affected by dwindling opportunities for interactive play in and out of school. Further, there are some data to suggest that children with asthma are less likely to participate in play in school compared to children without asthma, even when the opportunity is available.[15]

Urban children with asthma are also at risk for behavioral and academic difficulties;[16–21] comorbidities that have become more frequent in the past 10 years.[20] Since recess and physical activity are positively associated with school-based performance and behavior,[12] it is crucial to explore these associations among children with asthma. A closer look at the relationship between asthma symptoms, participation in interactive play, and socio-emotional and academic outcomes may provide useful insights into how best to counsel and support patients with asthma.

Our objectives of this study were to 1) describe IPP in school-aged children with persistent asthma, 2) determine if participation in IPP varies with asthma severity, and 3) evaluate the relationship between both asthma severity and IPP with socio-emotional and academic outcomes in this population. We hypothesized that children with more severe asthma would have less participation in IPP than children with milder symptoms, and that both asthma severity and a lack of IPP would negatively impact socio-emotional and academic outcomes.

METHODS

Settings and Participants

This study uses baseline data from the School-Based Telemedicine Enhanced Asthma Management (SB-TEAM) trial, collected from the 2012–2014 school years. We included 324 children ages 4 to 10 years old, enrolled from 41 preschools and elementary schools in urban Rochester, NY at the beginning of each school year (participation rate 78%). Eligible children were identified through Rochester City School District “medical-alert” forms that include caregiver-reported asthma diagnoses. Additionally, school nurses and health aides identified children who presented to their office with breathing problems or asthma symptoms. We performed telephone screening to assess eligibility for the parent study. Eligibility requirements included physician-diagnosed asthma, persistent asthma symptoms or poor asthma control (according to the NHLBI asthma severity classification guidelines),[22] ability to communicate in English, and not having any other chronic conditions that could interfere with the assessment of asthma symptoms. Caregivers of eligible children completed extensive in-home baseline surveys during the fall of 2012 and 2013. Written consent from caregivers and assent from children seven years of age and older were obtained during the home visit. We also contacted primary care providers of all eligible children to ensure agreement with their asthma diagnosis and eligibility for participation. The University of Rochester’s Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol.

Measures

Asthma Symptoms and Severity

We assessed asthma symptoms through a structured survey that asked caregivers to report the frequency of their child’s daytime and nighttime asthma symptoms, use of rescue medication and limitation of activity during the previous four weeks. Use of oral corticosteroids in the past 12 months was also assessed. Based on NHLBI guidelines,[22] children were classified as having ‘mild persistent’, ‘moderate persistent’ or ‘severe persistent’ asthma symptoms. These categories were then dichotomized into “mild persistent” and “moderate/severe persistent” groups for further analyses.

Participation in Interactive Physical Play (IPP)

We assessed participation in IPP in school based on caregiver report of child’s participation in physical education (PE) classes, activities at recess, and whether or not she/he was currently involved with an organized sports program. Along with the number of days of PE class their child had at school, caregivers reported if their child felt limited during PE class using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (totally limited) to 5 (not limited) based on the validated Children’s Health Survey for Asthma scale.[23] Responses were dichotomized into ‘limited’ (responses 1–4) or ‘not limited’ (response of 5). Caregivers also reported if their child had recess at school, and how they spent their recess time. Survey options for the type of recess activity included: 1 = ‘playing quiet games’, 2 = ‘playground games without much running’, or 3 = ‘activities involving a lot of running’. These responses were dichotomized into ‘runs during recess’ (response of 3) or ‘does not run during recess’ (response of 1 or 2). Finally, caregivers indicated if their child was currently involved with an organized sports program. Children were defined as participating in IPP if they had 1) PE class three or more days a week (based on New York State mandates for PE time and frequency in elementary schools[24, 25]), 2) ran during recess, or 3) were on a sports team.

Socio-emotional Functioning

Caregivers completed the Social, Emotional and Behavioral Functioning portion of the Parent Appraisal of Children’s Experiences (PACE) survey,[25] which was developed in the local community and previously administered to entering students in the school district. The scales allowed caregivers to answer questions about their child on a scale of 0 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). The PACE survey questions are categorized into four behavioral subscales: Positive Peer Social Skills (child makes friends easily, has many friends, talks easily with other children), Negative Peer Social Skills (fights with other children, hurts others, bothers other children), Shy/Anxious Behavior (gets nervous easily, is withdrawn, worries a lot) and Task Orientation (completes things he/she starts, has a short attention span, concentrates well). All PACE survey subscales from this sample have a Cronbach reliability score of >.60 (range .63-.84).

Academic Performance

We assessed academic performance using caregiver report of the child’s overall reading and math skills. Caregivers indicated if their child’s reading level was below, at or above their grade level, whether mathematics skills were below, at or above their grade level, and whether or not their child received learning services at school.

Covariates

We asked about standard demographic variables including child’s age, gender, and race, ethnicity, health insurance, and caregiver education level. We also assessed other factors related to behavioral and asthma outcomes in children, including caregiver depression[26–28] using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale,[29] and tobacco smoke exposure[30, 31] (child lives with one or more smokers).

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were completed using SPSS version 22.0 software (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Ill). We used bivariate and regression analyses to assess the relationship between asthma severity, IPP and socio-emotional and academic outcomes. Chi-square tests were used to assess the relationship between dichotomized asthma severity variable (mild persistent vs. moderate/severe persistent) and participation in any IPP. Multivariable regression models considered the independent relationship between asthma severity level as well as IPP with PACE subscale scores. The relationship between asthma severity, IPP participation, and academic outcomes (reading level at or above grade level, math skills at or above grade level, and receiving learning services at school) were also assessed using chi-square analysis. Regression models adjusted for age, gender, race, ethnicity, caregiver depression, insurance/Medicaid status, caregiver education level, and environmental tobacco smoke. We also repeated the multivariable analyses including the interaction of asthma severity (mild persistent vs. moderate-severe persistent)-by-interactive physical play. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

Overall, the SB-TEAM study enrolled 324 children (78% response rate) of whom 60% were male, 59% were Black, 34% were Other/Mixed Race, and 7% were White. Overall, 31% reported Hispanic ethnicity (86% Puerto Rican), 69% had Medicaid insurance, 68% had a preventive medication prescription, with an average age of 7.9 years (standard deviation 1.7). Nearly half (48%) of children had at least one smoker in the home. Among caregivers (90% mothers, 3% fathers, 3% grandparents, and 4% ‘other’ guardians), 19% reported an education level below high school and 33% scored 16 or higher on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D) indicating clinically significant risk of depression. All children had persistent asthma and 56% had moderate-severe asthma symptoms (Table 1).

Table 1:

Demographic Characteristics of Children and their Caregivers

| Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| CHILD CHARACTERISTICS | ||

| Gender | ||

| Male | 195 | 60.4 |

| Female | 128 | 39.6 |

| Race | ||

| Black | 191 | 59.0 |

| White | 23 | 7.1 |

| Other/Mixed Race | 110 | 34.0 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 101 | 31.2 |

| Non-Hispanic | 223 | 68.6 |

| Medicaid Enrollment | ||

| Enrolled | 224 | 69.1 |

| Not enrolled | 100 | 30.9 |

| Environmental Smoke Exposure | ||

| Smokers in the home | 156 | 48.1 |

| No Smokers in the home | 168 | 51.9 |

| Asthma Severity | ||

| Mild Persistent | 144 | 44.4 |

| Moderate-Severe Persistent | 180 | 55.6 |

| Has a Preventive Medication | ||

| Yes | 221 | 68.2 |

| No | 103 | 31.8 |

| CAREGIVER CHARACTERISTICS | ||

| Caregiver Education Level | ||

| Below High School | 63 | 19.4 |

| High School or Beyond | 261 | 80.6 |

| Caregiver Depression | ||

| CES-D < 16 | 215 | 67.2 |

| CES-D >= 16 | 105 | 32.8 |

CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale

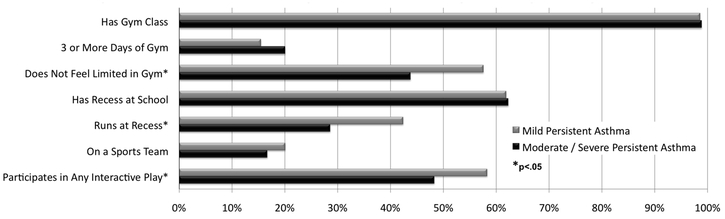

Study sample IPP participation

Overall, 98% of children had gym class in school, and 18% had 3 or more days of PE class each week. Half of the caregivers (50%) reported that their child felt physically limited during gym class. While 62% of children had any recess at school, approximately 1/3 of these children (34%) ran during recess. Finally, 18% of children in the study participated on an organized sports team. Cumulatively, 53% of all children participated in any form of IPP at school. There were no differences when comparing the various sociodemographic characteristics by IPP participation (data not shown).

Relationship between asthma severity and IPP participation

Figure 1 displays the relationship between asthma severity and IPP. We found that fewer children with moderate-severe persistent symptoms had no limitation in gym class, compared to children with mild persistent asthma symptoms (44% vs. 58%, p= .009). Further, fewer children with moderate-severe persistent symptoms ran during recess compared to than those with mild persistent symptoms (29% vs. 42%, p=.007). In general, fewer children with moderate-severe persistent symptoms participated in any form of IPP than children with mild persistent asthma (48% vs. 58%, p=.046).

Figure 1.

Asthma Severity and Interactive Physical Play Participation

Asthma Severity, IPP participation, and Socio-emotional Outcomes

Table 2 shows socio-emotional outcome scores for the children in the sample based on both asthma severity and participation in various types of IPP. There were no differences in socio-emotional outcomes by asthma severity. However, we found that children who participated in any IPP had more desirable socio-emotional outcomes across several measures. Children who participated in IPP had higher Positive Peer Social (3.34 vs 3.15, p=.005) and Task Orientation scores (2.73 vs 2.44, p<.001) and lower Shy/Anxious Behavior scores (2.29 vs 2.45, p=.025) compared to children who did not participate in IPP. Positive Peer Social and Task Orientation scores remained significant after controlling for covariates. There were no statistically significant differences found between the Negative Peer Social Scores and IPP participation.

Table 2:

Relationship of Children’s Asthma Severity and Interactive Physical Play with Socio-emotional Outcome Scores

| Asthma Symptoms Mean (SD) |

Mild Persistent (N=144) |

Moderate/Severe Persistent (N=180) |

P-value | Adjusted P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-emotional Scale Scores | ||||

| Positive Peer Social | 3.25 (.64) | 3.24 (.59) | 0.892 | 0.816 |

| Negative Peer Social | 2.00 (.72) | 2.04 (.76) | 0.695 | 0.933 |

| Shy/Anxious Behavior | 2.31 (.66) | 2.41 (.66) | 0.160 | 0.316 |

| Task Orientation | 2.63 (.72) | 2.56 (.74) | 0.392 | 0.968 |

|

Interactive Physical Play Mean (SD) |

Yes (N=171) |

No (N=153) |

P-value |

Adjusted P-value* |

| Socio-emotional Scale Scores | ||||

| Positive Peer Social | 3.34 (.57) | 3.15 (.64) | 0.005 | 0.007 |

| Negative Peer Social | 1.96 (.73) | 2.09 (.76) | 0.126 | 0.117 |

| Shy/Anxious Behavior | 2.29 (.68) | 2.45 (.62) | 0.025 | 0.070 |

| Task Orientation | 2.73 (.73) | 2.44 (.71) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Regression model controlled for race, gender, age, ethnicity, caregiver depression, caregiver education level, insurance/Medicaid enrollment and environmental tobacco smoke, severity, IPP

Relationship between Asthma Severity, IPP, and Caregiver-Reported Academic Outcomes

We also considered the relationship between both asthma severity and IPP with caregiver-reported academic outcomes (Table 3). Bi-variate analyses revealed no differences between asthma severity and the outcomes assessed. However, more caregivers of children who participated in IPP reported reading skills at or above grade level (73% vs. 58%, p=.008) and math skills at or above grade level (80% vs. 68%, p=.019) compared to those who did not participate. Furthermore, 25% of children who participated in IPP were receiving learning services at school compared to 35% of children who did not participate in IPP (p=.067), with p=.043 when controlling for covariates. All academic outcomes remained associated with IPP in regression analysis after controlling for child’s age, gender, race, ethnicity, insurance/Medicaid enrollment, asthma severity, caregiver education level, caregiver depression, and environmental tobacco smoke. When we repeated the analyses including the asthma severity-by-IPP interaction term, the interaction term was not statistically significant.

Table 3:

Relationship of Children’s Asthma Severity and Interactive Physical Play with Academic Outcomes

| Asthma Symptoms N (%) |

Mild Persistent (N=144) |

Moderate/Severe Persistent (N=180) |

P-value | Adjusted P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caregiver Reported Academic Outcomes | ||||

| Reading Skills At/Above Grade Level | 94 (67) | 110 (65) | 0.718 | 0.917 |

| Math Skills At/Above Grade Level | 103 (74) | 128 (75) | 0.794 | 0.330 |

| Learning Services | 42 (29) | 54 (31) | 0.807 | 0.781 |

|

Interactive Physical Play N (%) |

Yes (N=171) |

No (N=153) |

P-value |

Adjusted P-value* |

| Caregiver Reported Academic Outcomes | ||||

| Reading Skills At/Above Grade Level | 118 (73) | 86 (58) | 0.008 | 0.003 |

| Math Skills At/Above Grade Level | 130 (80) | 101 (68) | 0.019 | 0.008 |

| Learning Services | 43 (25) | 53 (35) | 0.067 | 0.043 |

Regression model controlled for race, gender, age, ethnicity, caregiver depression, caregiver education level, insurance/Medicaid enrollment and environmental tobacco smoke, severity, IPP

DISCUSSION

As hypothesized, we found low rates of participation in IPP among a large group of urban, low-income youth with asthma, and particularly among those with moderate to severe persistent asthma symptoms. We also found that those child who did not participate in IPP at school had worse scores on both measures of socio-emotional and academic performance. This suggests that participation in IPP at school is important for this population.

Previous studies have established the vast benefits of interactive playtime for children, ranging from healthy brain development to stronger interpersonal skills.[13] Interactive play is associated with improved emotional regulation, social competence, advanced language ability, and positive approaches to learning at school.[12] Thus, children who do not participate in interactive play risk slower social and academic growth.[32–35] This is particularly crucial for low-income youth with asthma, as both poverty and asthma are risk factors for worse behavior and learning outcomes.[7, 13, 36] Studies in this population have shown that children with persistent asthma symptoms score significantly worse on behavioral scales including measures of negative peer social skills, task orientation and shy/anxious behavior, when compared to children with intermittent symptoms or no symptoms.[18]

In this study we found no differences in outcomes by level of asthma severity. This may be related to the fact that only children with persistent asthma were enrolled in the study, and we did not have a comparison group of children without asthma or with mild intermittent asthma. It is important to note, however, that participation in physical activity has been shown to improve asthma-related outcomes, including improved quality of life in asthma patients.[37–40] Physical activity is encouraged by NHLBI asthma management guidelines;[22] activity at play or in organized sports has been recognized as an important component of long-term asthma control.[22] Urban youth with asthma who have less opportunity for and participation in IPP are therefore at increased risk for worsening asthma outcomes, which may contribute to further adverse socio-emotional and academic outcomes.

Over the past decade, there has been a continued national trend of reducing PE and playtime in school, including reducing or eliminating recess, particularly in schools with higher poverty rates.[13, 41] For children with asthma, lack of PE has been reported as a barrier to school-time physical activity.[42, 43] Further, in addition to being at highest risk of having reduced or no playtime in school, children living in poverty may have limited playtime outside of school due to lack of safe access to playgrounds and parks.[13] Neighborhood safety and lack of affordable after-school physical activity programs were found as community-level barriers to physical activity in minority schoolchildren with asthma.[42] While these factors are not unique for children with asthma, for urban minority children living in low-income communities, schools may provide the only opportunity for any physical activity.

We found that children with moderate to severe persistent asthma symptoms were least likely to participate in interactive play at school. The combined impact of their substantial symptom burden, along with reported limitations in activity and infrequent opportunity for play, warrant attention. Many children with asthma receive suboptimal preventive treatment,[5, 44] thus it is possible that more optimal symptom management for these children, along with opportunities for play, would allow them to not only participate more fully in activities but also to experience success in the classroom.

Our findings have implications for health care providers treating urban children with asthma. In addition to symptom screening, providers should assess for participation in physical activity inside and outside of school as well as socio-emotional and academic concerns. Optimizing therapy for these children should be in the context of the goal setting of having no limitation of activity due to symptoms. When counseling pediatric asthma patients and their caregivers, specifically highlighting the importance of IPP may encourage more participation from the child, with attention to the potential relationship between IPP and socio-emotional and academic outcomes in the children.

This study has several limitations. First, we relied on self-report of caregivers for all study data. Thus, there is a possibility of variable accuracy of caregivers’ knowledge of how much IPP their children participate in, along with the possibility of varying interpretation of “learning services” their child may or may not be receiving. However, caregiver report is frequently used for these measures, and has been shown to be reasonably accurate in assessing children’s activities and general academic performance.[45–49] Second, the study population was composed of urban, minority, low- income children with persistent asthma residing in Rochester, NY and our findings can only be generalized to similar populations. Furthermore, there may be other medical, social and environmental factors contributing to decreased IPP that were not accounted for in this study. Examples of such factors include social anxiety in children, parent perception of limited physical ability in children with asthma, physical education teachers’ perception that ‘sitting out’ of activities may be of more benefit to children with asthma, and general concern about children developing asthma symptoms during IPP. Lastly, as mentioned, we did not have a comparison group of children without asthma or with mild intermittent asthma in this study.

Conclusions

We found that many urban, school-aged children with persistent asthma were reported by caregivers as not participating in IPP at school. The level of participation was lowest among children with moderate-severe persistent symptoms. Children with less IPP were reported to display worse socio-emotional and academic outcomes than their more active peers. These findings support the need for continued efforts to ensure optimal preventive asthma care and to advocate for daily IPP and other physical activity opportunities for minority children with asthma attending urban schools.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This study was supported by the R01HL079954 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI).

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akinbami LJ, Simon AE, Rossen LM. Changing Trends in Asthma Prevalence Among Children. Pediatrics. 2016;137(1). doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-2354. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4755484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flores G, Snowden-Bridon C, Torres S, Perez R, Walter T, Brotanek J, et al. Urban minority children with asthma: substantial morbidity, compromised quality and access to specialists, and the importance of poverty and specialty care. J Asthma. 2009;46(4):392–8. doi: 10.1080/02770900802712971. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akinbami LJ, Moorman JE, Bailey C, Zahran HS, King M, Johnson CA, et al. Trends in asthma prevalence, health care use, and mortality in the United States, 2001–2010. NCHS data brief. 2012(94):1–8. PubMed PMID: . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crocker D, Brown C, Moolenaar R, Moorman J, Bailey C, Mannino D, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in asthma medication usage and health-care utilization: data from the National Asthma Survey. Chest. 2009;136(4):1063–71. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-0013. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halterman JS, Auinger P, Conn KM, Lynch K, Yoos HL, Szilagyi PG. Inadequate therapy and poor symptom control among children with asthma: findings from a multistate sample. Ambul Pediatr. 2007;7(2):153–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2006.11.007. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reznik M, Bauman LJ, Okelo SO, Halterman JS. Asthma identification and medication administration forms in New York City schools. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015;114(1):67–8 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2014.10.006. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4274201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Basch CE. Healthier students are better learners: a missing link in school reforms to close the achievement gap. J Sch Health. 2011;81(10):593–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00632.x. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmier JK, Manjunath R, Halpern MT, Jones ML, Thompson K, Diette GB. The impact of inadequately controlled asthma in urban children on quality of life and productivity. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007;98(3):245–51. Epub 2007/03/24. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60713-2. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moonie SA, Sterling DA, Figgs L, Castro M. Asthma status and severity affects missed school days. J Sch Health. 2006;76(1):18–24. Epub 2006/02/07. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2006.00062.x. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haselkorn T, Fish JE, Zeiger RS, Szefler SJ, Miller DP, Chipps BE, et al. Consistently very poorly controlled asthma, as defined by the impairment domain of the Expert Panel Report 3 guidelines, increases risk for future severe asthma exacerbations in The Epidemiology and Natural History of Asthma: Outcomes and Treatment Regimens (TENOR) study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124(5):895–902 e1–4. Epub 2009/10/09. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.07.035. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akinbami LJ, Moorman JE, Liu X. Asthma prevalence, health care use, and mortality: United States, 2005–2009. Natl Health Stat Report. 2011;32:1–14. Epub 2011/03/02. PubMed PMID: . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bulotsky-Shearer RJ, Bell ER, Romero SL, Carter TM. Preschool interactive peer play mediates problem behavior and learning for low-income children. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2012;33(1):53–65. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2011.09.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Milteer RM, Ginsburg KR. The importance of play in promoting healthy child development and maintaining strong parent-child bond: focus on children in poverty. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1):e204–13. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2953. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee SM, Burgeson CR, Fulton JE, Spain CG. Physical education and physical activity: results from the School Health Policies and Programs Study 2006. J Sch Health. 2007;77(8):435–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00229.x. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walker TJ, Reznik M. In-school asthma management and physical activity: children’s perspectives. J Asthma. 2014;51(8):808–13. Epub 2014/05/07. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2014.920875. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPmc4165729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McQuaid EL, Kopel SJ, Nassau JH. Behavioral adjustment in children with asthma: a meta-analysis. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2001;22(6):430–9. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Booster GD, Oland AA, Bender BG. Psychosocial Factors in Severe Pediatric Asthma. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2016;36(3):449–60. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2016.03.012. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Halterman JS, Conn KM, Forbes-Jones E, Fagnano M, Hightower AD, Szilagyi PG. Behavior problems among inner-city children with asthma: findings from a community-based sample. Pediatrics. 2006;117(2):e192–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1140. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klinnert MD, McQuaid EL, McCormick D, Adinoff AD, Bryant NE. A multimethod assessment of behavioral and emotional adjustment in children with asthma. J Pediatr Psychol. 2000;25(1):35–46. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blackman JA, Conaway MR. Changes over time in reducing developmental and behavioral comorbidities of asthma in children. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2012;33(1):24–31. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3182396895. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halterman JS, Montes G, Aligne CA, Kaczorowski JM, Hightower AD, Szilagyi PG. School readiness among urban children with asthma. Ambul Pediatr. 2001;1(4):201–5. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Asthma E, Prevention P. Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3): Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma-Summary Report 2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120(5 Suppl):S94–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.09.043. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Asmussen L, Olson LM, Grant EN, Fagan J, and Weiss KB. Reliability and Validity of the Children’s Health Survey for Asthma. Pediatrics. 1999;104(6). doi: 10.1542/peds.104.6.e71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.NYSED. NYS Learning Standards and Core Curriculum New York: New York State Department of Education; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Law W, Montes G, Hightower AD, Lotyczewski BS, Halterman JS. Parent-Child Rating Scale (PCRS): A parent-reported questionnaire to assess social and emotional functioning in children Rochester, NY: Children’s Institute, 2012. November. Report No.: T12–017. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bartlett SJ, Krishnan JA, Riekert KA, Butz AM, Malveaux FJ, Rand CS. Maternal depressive symptoms and adherence to therapy in inner-city children with asthma. Pediatrics. 2004;113(2):229–37. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pak L, Allen PJ. The impact of maternal depression on children with asthma. Pediatr Nurs. 2012;38(1):11–9, 30. PubMed PMID: . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shalowitz MU, Berry CA, Quinn KA, Wolf RL. The relationship of life stressors and maternal depression to pediatric asthma morbidity in a subspecialty practice. Ambul Pediatr. 2001;1(4):185–93. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1997;1(3):385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fagnano M, Conn KM, Halterman JS. Environmental tobacco smoke and behaviors of inner-city children with asthma. Ambul Pediatr. 2008;8(5):288–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2008.04.002. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2597107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ciaccio CE, DiDonna A, Kennedy K, Barnes CS, Portnoy JM, Rosenwasser LJ. Secondhand tobacco smoke exposure in low-income children and its association with asthma. Allergy and asthma proceedings : the official journal of regional and state allergy societies. 2014;35(6):462–6. doi: 10.2500/aap.2014.35.3788. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4210654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Egger JR, Konty KJ, Bartley KF, Benson L, Bellino D, Kerker B. Childhood Obesity Is a Serious Concern in New York City: Higher Levels of Fitness Associated with Better Academic Performance NYC Vital Signs. Vol 8 New York, NY: New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene and New York City Department of Education; 2009:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jarrett OS, Maxwell DM, Dickerson C, Hoge P. Impact of Recess on Classroom Behavior: Group Effects and Individual Differences. The Journal of Educational Research. 1998;92:6. [Google Scholar]

- 34.The Health Consequences of Involuntary Smoking. A Report of the Surgeon General Rockville, MD: U.S: Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control, Center for Health Promotion and Education, Office on Smoking and Health, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murray R, Ramstetter C, Council on School H, American Academy of P. The crucial role of recess in school. Pediatrics. 2013;131(1):183–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2993. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bussing R, Halfon N, Benjamin B, Wells KB. Prevalence of behavior problems in US children with asthma. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1995;149(5):565–72. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clark CJ. The role of physical training in asthma. Chest. 1992;101(5 Suppl):293S–8S. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lucas SR, Platts-Mills TA. Physical activity and exercise in asthma: relevance to etiology and treatment. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115(5):928–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.01.033. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Orenstein DM. Pulmonary problems and management concerns in youth sports. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2002;49(4):709–21, v-vi. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Satta A Exercise training in asthma. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2000;40(4):277–83. PubMed PMID: . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rebell MA, Wolff JR, Rodgers JR. Students’ Constitutional Right to a Sound Basic Education: New York State’s Unfinished Agenda. New York, NY: Teachers College, Columbia university, Equity CfE; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kornblit A, Cain A, Bauman LJ, Brown NM, Reznik M. Parental Perspectives of Barriers to Physical Activity in Urban Schoolchildren With Asthma. Acad Pediatr. 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2017.12.011. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cain A, Reznik M. The Principal and Nurse Perspective on Gaps in Asthma Care and Barriers to Physical Activity in New York City Schools: A Qualitative Study. Health Educ Behav. 2017:1090198117736351. doi: 10.1177/1090198117736351. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burgess S, Sly P, Devadason S. Adherence with preventive medication in childhood asthma. Pulm Med. 2011;2011:973849. doi: 10.1155/2011/973849. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3109699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Burdette HL, Whitaker RC, Daniels SR. Parental report of outdoor playtime as a measure of physical activity in preschool-aged children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158(4):353–7. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.4.353. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Galper A, Wigfield A, Seefeldt C. Head Start Parents’ Beliefs about Their Children’s Abilities, Task Values, and Performances on Different Activities. Child Dev. 1997;68(5):897–907. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1997.tb01969.x. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hall NE, Segarra VR. Predicting academic performance in children with language impairment: the role of parent report. J Commun Disord. 2007;40(1):82–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jcomdis.2006.06.001. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lang DM, Butz AM, Duggan AK, Serwint JR. Physical activity in urban school-aged children with asthma. Pediatrics. 2004;113(4):e341–6. Epub 2004/04/03. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Holderness H, Chin N, Ossip DJ, Fagnano M, Reznik M, Halterman JS. Physical activity, restrictions in activity, and body mass index among urban children with persistent asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;118(4):433–8. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2017.01.014. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5385295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]