Abstract

Purpose:

While radical nephroureterectomy (RNU) is the gold standard treatment for upper tract urothelial carcinoma (UTUC), select patients may benefit from endoscopic treatment (ET). European Urological Association guidelines recommend ET for patients with low-risk (LR) disease: unifocal, <2cm, low-grade lesions without local invasion. To inform the utility of ET, we compare the overall survival (OS) of patients receiving ET and RNU using current and previous guidelines of LR disease.

Materials and Methods:

Patients with non-metastatic, cT1 or less UTUC diagnosed in 2004–2012 were collected from the National Cancer Database. OS was analyzed with inverse-probability of treatment weighted Cox proportional hazard regression. Analyses were conducted for LR disease under updated (size <2cm) and previous guidelines (size <1cm).

Results:

Patients who were older, healthier, and treated at an academic facility had higher odds of receiving ET. In 851 identified patients with LR disease, RNU was associated with increased OS compared with ET (p=0.006); however, there was no difference between ET and RNU (p=0.79, n=202) under previous guidelines (size <1cm). In otherwise LR patients, the largest tumor size with no difference between ET and RNU was ≤1.5cm (p=0.07).

Conclusions:

RNU is associated with improved survival when compared with ET in the management of LR UTUC using current guidelines with a size threshold of <2cm. In appropriately selected LR patients, we find no difference between RNU and ET up to a tumor size of ≤1.5cm. However, in the absence of prospective studies, the usage of ET is best left up to clinician discretion.

Keywords: Urothelial carcinoma, radical nephroureterectomy, endoscopic therapy, ureter, renal pelvis

1. Introduction

Upper tract urothelial carcinoma (UTUC) accounts to 5–10% of urothelial carcinomas and are two to four times more likely to be invasive at diagnosis compared with tumors of the urinary bladder.1,2 While radical nephroureterectomy (RNU) with bladder cuff excision is the gold standard treatment for UTUC, kidney-preserving approaches, such as endoscopic treatment (ET), can also be used in selected patients with low-risk disease.3,4 ET is useful in patients who are poor candidates for surgery, such as the elderly, those with significant comorbidity, or those with compromised renal function.

Current European Urological Association (EUA) guidelines recommend ET, including endoscopic laser ablation, with close follow-up as first line treatment in patients with low-risk (LR) disease: a unifocal, small (<2cm), histologically low-grade (LG) tumor with no evidence of invasion on imaging.5 These 2017 guidelines represent a change from previous EUA guidelines where tumor size was limited to <1cm.4 For high-risk tumors or recurrence following ET, RNU is the recommended definitive treatment option and can be approached open, laparoscopically or robotically.

Studies comparing RNU with ET have shown a benefit of RNU over ET, even in moderate or LG disease. Single institution studies have shown improvements in recurrence-free survival (RFS) in patients receiving RNU compared with ET.3 Similarly, matched retrospective analysis using Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER)-Medicare data have shown a consistent association with improved overall survival (OS) among patients undergoing RNU compared with ET, while results regarding cancer-specific survival (CSS) have been mixed.6,7

No studies have fully investigated the outcomes for ET and RNU in guideline defined LR UTUC. Similarly, no studies have described which patients are more likely to receive ET compared to RNU. A better understanding of which patients may benefit from ET instead of RNU may lead to better protection of renal function and possibly reduce the number of UTUC patients eventually needing dialysis.

In our analysis, we aim to compare the impact of RNU and ET on survival in guideline-defined LR disease using a large national database. We also analyze utilization patterns of RNU and ET based on disease and patient characteristics. We hypothesize that ET and RNU will have similar overall survival in LR disease under current EUA guideline.

2. Data & Methods

2.1. Data Source

The National Cancer Database (NCDB) is an ongoing hospital registry-based database compiled from more than 1,500 Commission on Cancer accredited centers and is sponsored jointly by the American College of Surgeons and the American Cancer Society. The NCDB captures more than 70% of newly diagnosed cancers in the United States and represents more than 34 million historical records beginning in 2004 and updated with new diagnoses annually.8

2.2. Study Population

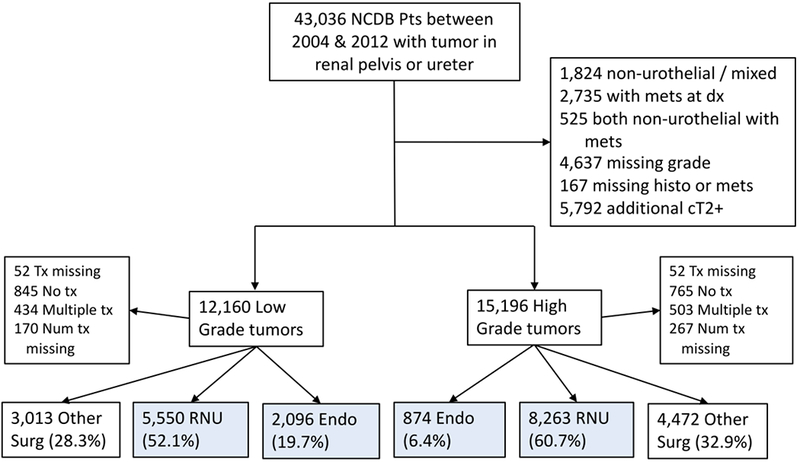

Patients with a primary diagnosis of UTUC were identified in the NCDB database (site code C659 for ureter, C659 for renal pelvis) who were diagnosed between 2004 and 2012, with outcome information available through 2014. Only those patients with histologically confirmed urothelial cell carcinoma (codes 8120 and 8130) were included. Patients who received more than one endoscopic or surgical treatment greater than 90 days apart were excluded as no data is available in the NCDB on prior treatments; procedures within 90 days may include biopsy to inform diagnosis and are less likely to indicate treatment failure. Patients with metastatic disease at presentation, missing histological grade or clinical stage T2 on diagnosis were excluded. ET was limited to local tumor destruction or excision: either photodynamic therapy, electrocautery, cryosurgery, laser ablation or excision, thermal ablation, polypectomy, or excisional biopsy (codes 10–15, 20–27). RNU was limited to nephroureterectomy including bladder cuff (code 40). Other surgical interventions such as partial nephrectomy or ureterectomy were excluded from analysis of treatment outcomes (Figure 1). Further refinements were made for the comparative and OS analysis for guideline defined LR patients: only patients with tumors <2cm, LG histology, and clinically stage 1 or less were included.5

Figure 1 -.

Study population extracted from NCDB patients with reported tumors of the ureter or renal pelvis. Blue indicates patients meeting survival analysis criteria.

2.3. Study Variables

Our independent variable of interest was treatment type (ET or RNU). Other covariates included patient specific demographics, such as age, gender, race, Charlson-Deyo comorbidity (CDC) score9, insurance status, academic/research treatment facility, ZIP code income quartile, ZIP code percent without high school diploma quartile, and urban/rural residence status. Pathologic characteristics included tumor grade as defined by ICD-O-3 code (LG defined as grade I or II, HG as grade III or IV), tumor size (categorized as <3cm, ≥3cm, unknown), clinical stage (composite <1,1, unknown). Our dependent variable and primary outcome was OS.

2.4. Statistical Methods

First, we performed binomial regression to evaluate trends in endoscopic interventions versus all other surgical procedures over time by tumor location: ureter vs renal pelvis. Next, we compared characteristics of patients receiving RNU versus ET using a multivariable binomial model. Variables included in this model demonstrated a statistically significant difference between treatment groups in a univariate chi-squared analysis. Next, we evaluated the difference in OS in patients receiving primary ET compared with RNU for different subsets of patients. In order to balance pre-treatment confounders, we used an inverse probability of treatment weighted (IPTW) approach.10 This method is useful for adjusting for measured bias between groups, however this approach does not account for unmeasured confounders that may affect treatment selection. First, we estimated propensity scores predicting type of treatment received (ET or RNU). Categorical variables with missing data were included as a unique factor level. Next, standardized IPTW scores were calculated based on the propensity scores and then truncated to the 1st and 99th percentiles to reduce bias.11,12 Weights were standardized by using mean probability of receiving ET or RNU in the numerator of the IPTW calculation. Weighted Cox proportional hazard models were used to estimate hazard ratios for OS for patients receiving ET vs RNU. Weighted Kaplan-Meier curves were used to estimate median and 5-year OS. Bonferroni correction was used to adjust for repeated testing. Analysis was carried out in R version 3.3.1.13

3. Results

3.1. Trends in usage of endoscopic interventions

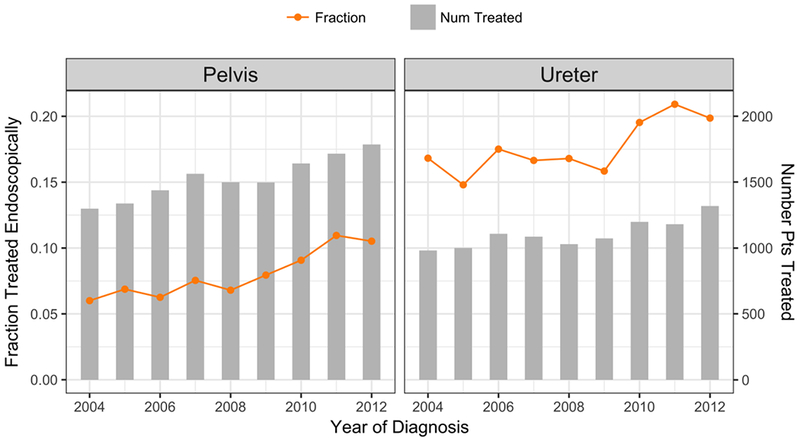

Of the 43,036 patients in the NCDB with tumors of the ureter and renal pelvis between 2004 and 2012, a total of 24,268 met inclusion criteria for this portion of the analysis (Figure 1). There has been a small but gradual increase in the proportion of patients receiving definitive ET between 2004 and 2012. In 2004, 6.0% of pelvis tumor treatments were ET compared with 10.5% in 2012 (trend p<0.001). For tumors of the ureter, 16.8% were treated with ET in 2004 compared to 19.7% in 2012 (trend p<0.001).

ET has been used occasionally to treat patients with HG UTUC. In 2012, 7.6% of treated patients with HG UTUC received ET: 5.2% patients with tumors of the pelvis compared with 11.2% of patients with tumors of the ureter.

3.2. Differences between patients receiving ET versus RNU

Between 2004 and 2012, 16,783 patients meet inclusion criteria for this portion of analysis, 2,970 (17.7%) received ET and 13,813 (82.3%) underwent RNU (Figure 1). Patients receiving ET differed systematically from those receiving RNU on univariate analysis (Table 1). Regarding tumor location, 61% of ET patients had tumors of the ureter compared with 35.2% of RNU patients. ET patients were more likely to have LG tumors, have lower stage tumors and have smaller tumors or tumors missing size information. ET patients were also more likely to be male, have lower CDC score, older age, and have Medicaid as a form of insurance. Finally, a higher fraction of patients receiving ET lived in wealthier areas, urban area and received treatment at an academic institution.

Table 1 -.

Study population characteristics by treatment recieved

| Treatment | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radical NU | Endoscopic | P-Value | |||||

| Variable | Num | Perc | Num | Perc | |||

| Total | 13,813 | 82.3% | 2,970 | 17.7% | |||

| Tumor Characteristics | Location | ||||||

| Pelvis | 8,945 | 64.8% | 1,159 | 39.0% | <0.001 | ||

| Ureter | 4,868 | 35.2% | 1,811 | 61.0% | |||

| Grade | |||||||

| High | 8,263 | 59.8% | 874 | 29.4% | <0.001 | ||

| Low | 5,550 | 40.2% | 2,096 | 70.6% | |||

| Clin Stage | |||||||

| <1 | 3,465 | 25.1% | 1,636 | 55.1% | <0.001 | ||

| 1 | 2,601 | 18.8% | 551 | 18.6% | |||

| Missing | 7,747 | 56.1% | 783 | 26.4% | |||

| Size | |||||||

| <3cm | 4,853 | 35.1% | 855 | 28.8% | <0.001 | ||

| >=3cm | 7,180 | 52.0% | 251 | 8.5% | |||

| Missing | 1,780 | 12.9% | 1,864 | 62.8% | |||

| Personal Characteristics | Gender | ||||||

| Female | 5,678 | 41.1% | 1,105 | 37.2% | <0.001 | ||

| Male | 8,135 | 58.9% | 1,865 | 62.8% | |||

| CDC Score | |||||||

| 0 | 9,179 | 66.5% | 2,136 | 71.9% | <0.001 | ||

| 1 | 3,459 | 25.0% | 624 | 21.0% | |||

| 2+ | 1,175 | 8.5% | 210 | 7.1% | |||

| Age | |||||||

| <65 | 3,599 | 26.1% | 552 | 18.6% | <0.001 | ||

| 65-79yo | 6,953 | 50.3% | 1,379 | 46.4% | |||

| 80+ | 3,261 | 23.6% | 1,039 | 35.0% | |||

| Race | |||||||

| White, non-hisp | 12,777 | 92.5% | 2,775 | 93.4% | 0.07 | ||

| Other | 893 | 6.4% | 165 | 5.6% | |||

| Missing | 143 | 1.0% | 30 | 1.0% | |||

| Insurance | |||||||

| Private | 3,845 | 27.8% | 647 | 21.8% | <0.001 | ||

| Medicare | 9,199 | 66.6% | 2,163 | 72.8% | |||

| Medicaid | 382 | 2.8% | 93 | 3.1% | |||

| None | 202 | 1.5% | 29 | 1.0% | |||

| Missing | 185 | 1.3% | 38 | 1.3% | |||

| Local Characteristics | Income | ||||||

| <38k | 2,081 | 15.1% | 397 | 13.4% | 0.005 | ||

| 38-48k | 3,189 | 23.1% | 656 | 22.1% | |||

| 48-63k | 3,795 | 27.5% | 799 | 26.9% | |||

| 63k+ | 4,509 | 32.6% | 1,060 | 35.7% | |||

| Missing | 239 | 1.7% | 58 | 2.0% | |||

| Education | |||||||

| 21%+ no HS | 1,788 | 12.9% | 354 | 11.9% | 0.48 | ||

| 13-21% no HS | 3,409 | 24.7% | 739 | 24.9% | |||

| 7-13% no HS | 4,783 | 34.6% | 1,028 | 34.6% | |||

| <7% no HS | 3,602 | 26.1% | 794 | 26.7% | |||

| Missing | 231 | 1.7% | 55 | 1.9% | |||

| Rural/Urban | |||||||

| Rural | 2,324 | 16.8% | 451 | 15.2% | 0.03 | ||

| Urban | 10,978 | 79.5% | 2,412 | 81.2% | |||

| Missing | 511 | 3.7% | 107 | 3.6% | |||

| Facility | |||||||

| Academic | 4,757 | 34.4% | 1,202 | 40.5% | <0.001 | ||

| Other | 8,982 | 65.0% | 1,757 | 59.2% | |||

| Missing | 74 | 0.5% | 11 | 0.4% | |||

On multivariable analysis, tumor characteristics were strong predictors of the type of treatment received: LG, lower stage and small or unknown size tumors were associated with receiving ET compared with RNU (Table 2). Older age, lower CDC score and receiving care at an academic facility were independently associated with a higher likelihood of receiving ET versus RNU. Male patients were also more likely to receive ET compared with female patients.

Table 2 -.

Multivariate analysis of factors associated with receiving primary Endoscopic treatment versus RNU

| Variable | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | ||||

| Pelvis | 1.00 | |||

| Ureter | 2.06 | (1.86, 2.27) | <0.001 | |

| Grade | ||||

| Low | 1.00 | |||

| High | 0.34 | (0.3, 0.37) | <0.001 | |

| Size | ||||

| <3cm | 1.00 | |||

| >=3cm | 0.24 | (0.2, 0.28) | <0.001 | |

| Missing | 5.83 | (5.22, 6.5) | <0.001 | |

| Clinical stage | ||||

| <1 | 1.00 | |||

| 1 | 0.70 | (0.61, 0.8) | <0.001 | |

| Missing | 0.32 | (0.28, 0.36) | <0.001 | |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 1.00 | |||

| Male | 1.20 | (1.09, 1.33) | <0.001 | |

| CDC Score | ||||

| 0 | 1.00 | |||

| 1 | 0.79 | (0.7, 0.89) | <0.001 | |

| 2+ | 0.72 | (0.6, 0.87) | <0.001 | |

| Age | ||||

| <65 | 1.00 | |||

| 65-79yo | 1.28 | (1.08, 1.51) | 0.004 | |

| 80+ | 2.38 | (1.98, 2.85) | <0.001 | |

| Insurance | ||||

| Medicaid | 1.00 | |||

| None | 0.61 | (0.35, 1.04) | 0.072 | |

| Medicare | 0.73 | (0.54, 0.99) | 0.039 | |

| Private | 0.70 | (0.52, 0.95) | 0.021 | |

| Missing | 0.66 | (0.39, 1.11) | 0.12 | |

| Income | ||||

| <38k | 1.00 | |||

| 38-48k | 1.16 | (0.98, 1.37) | 0.085 | |

| 48-63k | 1.14 | (0.96, 1.34) | 0.13 | |

| 63k+ | 1.22 | (1.04, 1.44) | 0.018 | |

| Missing | 1.60 | (0.98, 2.61) | 0.059 | |

| Rural/Urban | ||||

| Rural | 1.00 | |||

| Urban | 0.89 | (0.62, 1.27) | 0.53 | |

| Missing | 0.89 | (0.62, 1.27) | 0.53 | |

| Facility | ||||

| Non-Academic | 1.00 | |||

| Academic | 1.58 | (1.43, 1.75) | <0.001 | |

| Missing | 0.93 | (0.4, 1.97) | 0.85 | |

| Year | ||||

| 2004 | 1.00 | |||

| 2005 | 1.00 | (0.79, 1.26) | 0.97 | |

| 2006 | 1.35 | (1.07, 1.69) | 0.01 | |

| 2007 | 1.23 | (0.99, 1.54) | 0.065 | |

| 2008 | 1.14 | (0.91, 1.43) | 0.26 | |

| 2009 | 1.03 | (0.82, 1.29) | 0.8 | |

| 2010 | 1.44 | (1.16, 1.79) | 0.001 | |

| 2011 | 1.70 | (1.37, 2.11) | <0.001 | |

| 2012 | 1.81 | (1.46, 2.24) | <0.001 | |

3.3. IPTW analysis of OS in Low-Risk UTUC

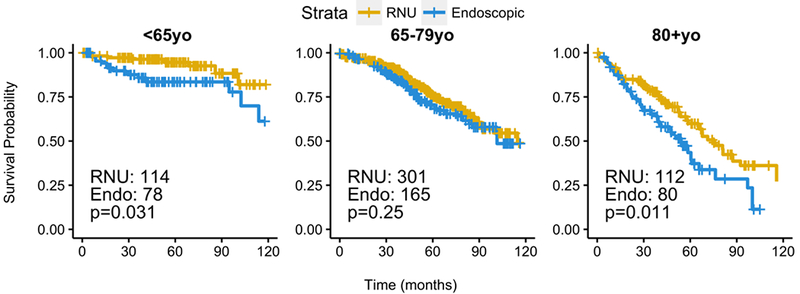

Using current guidelines, we identified 851 patients meeting criteria for LR UTUC tumors under updated 2017 guidelines: tumor size <2cm, LG, clinical stage I or less. Of these patients, 323 (38%) received ET and 527 (62%) received RNU. ET was associated with worse survival compared with RNU (HR 1.43, CI 1.11–1.85, p=0.006; 5-year OS 75.2% for RNU and 69.3% for ET; median OS of 116 months for RNU, 101 months for ET). Analysis stratified by age-group also showed a significantly lower HR for ET in patients <65 and ≥80 (Figure 3).

Figure 3 -. Stratified analysis of low risk UTUC tumors by age group for EUA 2017 guidelines.

P-values from IPTW-weighted proportional cox proportional hazard model.

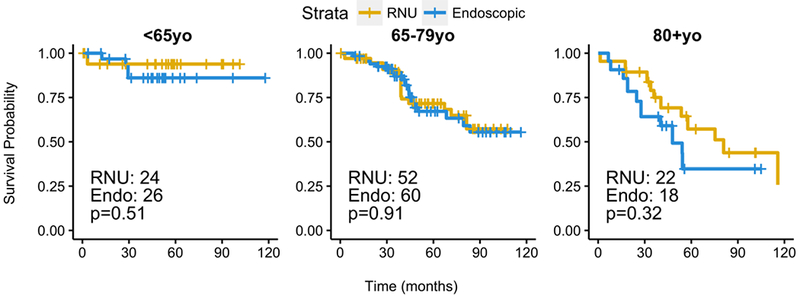

Using the previous 2015 guidelines for LR tumors (size <1cm), 202 patients were identified, 104 (51%) who received ET and 98 (49%) received RNU. There was no significant difference between ET and RNU in this cohort (HR 1.08, CI 0.63–1.82, p=0.79; 5-year OS 73.7% for RNU and 69.2% for ET; median OS of 116 months for RNU, >140 months for ET). Analysis stratified by age-group also showed no significant differences between ET and RNU (Figure 4).

Figure 4 -. Stratified analysis of low risk UTUC tumors by age group for EUA 2015 guidelines.

P-values from IPTW-weighted proportional cox proportional hazard model.

In order to find the largest tumor size associated with no difference in OS between ET and RNU, repeated IPTW HR models were built for LR patients with tumor size ≤1,0cm and increasing iteratively by 0.1cm until the difference was significant, using Bonferroni correction to adjust for repeated testing. The largest tumor size with no associated difference between ET and RNU was size ≤1.5cm (adjusted p=0.07). RNU was associated with better survival than ET in LR patients when tumors sized ≥1.6cm were included in analysis (adjusted p=0.01).

4. Discussion

While urothelial carcinoma of the upper urinary tract is a rare malignancy, it is one that disproportionately affects elderly patients who often suffer from significant comorbidities. As such, minimally invasive treatment options, such as ET, are an important tool in the armamentarium of the urologist treating this disease. In our current study, we evaluated the differences in OS between treatment type (ET versus RNU) in patients with LR disease to understand the impact of recent changes to guidelines for management. Our study has three important findings. First, ET is increasing in use compared with other surgical treatments of UTUC, though it remains used in a small minority of cases. Second, compared with patients receiving RNU, those treated with ET were more likely to be older, have fewer comorbidities and are treated at an academic institution. Finally, we found ET to be associated with worse survival when compared with RNU in selected LR patients based on recently updated guideline recommendations; however, survival was not different between the treatment modalities when previous, more conservative, guidelines were used to select LR patients.

The small but statistically significant increases in usage of ET likely corresponds to improvements in endoscopic optics and ablative technologies that allow the urologist the opportunity to manage these patients without extirpative surgery.14 A substantial number of patients receiving ET had HG disease in our cohort, counter to current guidelines suggesting that ET be limited to patients with LG disease. Of patients who received ET, 29% had HG UTUC, and of all HG UTUC patients who received treatment, 6.4% received ET. On multivariable analysis, we found patients receiving care at academic facilities were 50% more likely to be treated with ET compared with those in non-academic settings consistent with these being more specialized procedures.

In the analysis of confirmed LR patients, we found patients receiving ET to have a higher mortality rate than those receiving RNU. When 2015 EUA guidelines suggesting tumor size be limited to <1cm were used, we found no difference between ET and RNU.4 Our exploratory analysis of tumor size indicates that patients with unifocal, low-grade, non-invasive UTUC may benefit equally from ET and RNU with tumor sizes equal or less than 1.5cm. This size threshold sits between that used by current and previous EUA guidelines. In the group of patients identifiable as low risk under more restrictive 2015 EUA guidelines in the NCDB, 49% with potentially ET-manageable disease received RNU. This represents an opportunity for improvement and highlights the importance of referral to centers with experience providing definitive ET-based care.

Similar to our study, two prior database analyses have shown a benefit of RNU over ET in terms of OS in moderate or LG non-muscle invasive disease.6,7 Results from single-institution studies of LG UTUC have been mixed with one study of 129 patients finding a significant increase in PFS and CSS for RNU versus ET3 and another of 96 patients finding no difference in CSS or OS.15 A recent meta-analysis of 1,002 patients with localized UTUC found no difference in CSS or OS by treatment modality.16 Another meta-analysis of kidney-sparing treatments of UTUC found no difference between RNU and ET in low-grade noninvasive tumors.17 Notably tumor size was not included in any of these analyses. No prospective trials exist that compare outcomes of RNU and ET.

Our study has several limitations. First, reporting standards in NCDB are such that patients receiving multiple surgical treatments cannot be analyzed as only the final, definitive surgical treatment is recorded. As has been described in other studies, roughly 50% of patients with LG UTUC initially treated with ET have recurrence and require RNU within a median period of 9 months.6 As we excluded patients receiving multiple treatments, we likely over-estimate the effectiveness of ET. Second, a large proportion (63%) of ET patients were missing tumor size, making a larger analysis of LR disease difficult.5 However, there is reason to believe that many of these tumors missing size data were small as 93% were clinical stage I or less. Third, our analysis is limited to endoscopic ablation or resection versus RNU, and does not examine other kidney-sparing surgical techniques, such as segmental ureterectomy, which may have similar outcomes in selected patients.17,18 Fourth, our analysis is limited to OS as information on CSS or PFS is not available in the NCDB. Finally, while propensity score-based methods are effective ways to control for selection bias on known covariates, there may be other unrecorded characteristics influencing treatment selection for UTUC. Despite these factors, we hope our findings assist clinicians when discussing and deciding on treatment options for UTUC with their patients.

5. Conclusion

We find ET to be inferior to RNU with regards to OS in the management of LR UTUC under recently updated guidelines. This effect was not uniform across age groups suggesting some of these patients may safely benefit from kidney-sparing interventions. Under previous guidelines using a smaller tumor size cut off for LR disease, there was no difference in OS between ET and RNU. Further analysis suggests that there is no difference in OS in patients with tumor size less than or equal to 1.5cm with otherwise LR disease. Prospective studies are needed to rigorously evaluate the benefits of one treatment over another.

Figure 2 -.

Number of patients with UTUC treated by year and tumor location. Orange line indicates the fraction of these primary treatments that are endoscopic.

6. Acknowledgments and Conflicts of Interest

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Loan Repayment Program (L30 CA154326 (Principal Investigator: KC)), the STOP Cancer Foundation (Principal Investigator: KC), and the H & H Lee Surgical Resident Research Award (Recipient: ATL). There are no potential conflicts of interest to disclose. This research involved an anonymized national patient database and did therefore not require informed consent.

8. Abbreviations

- CSS

Cancer specific survival

- CDC

Charlson-Deyo comorbidity

- ET

Endoscopic treatment

- EUA

European Urological Association

- HR

Hazard ratio

- HG

High grade

- ITPW

Inverse probability of treatment weighted

- LG

Low grade

- LR

Low risk

- NCDB

National Cancer Database

- OS

Overall survival

- PFS

Progression free survival

- RNU

Radical nephrectomy

- UTUC

Upper tract urothelial carcinoma

References

- 1.Froemming A, Potretzke T, Takahashi N, Kim B. Upper Tract Urothelial Cancer. European Journal of Radiology. 2017;98:1–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2017.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Margulis V, Shariat SF, Matin SF, et al. Outcomes of radical nephroureterectomy: A series from the Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinoma Collaboration. Cancer. 2009;115(6):1224–1233. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cutress ML, Stewart GD, Tudor ECG, et al. Endoscopic Versus Laparoscopic Management of Noninvasive Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinoma: 20-Year Single Center Experience. The Journal of Urology. 2013;189(6):2054–2061. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rouprêt M, Babjuk M, Compérat E, et al. European Association of Urology Guidelines on Upper Urinary Tract Urothelial Cell Carcinoma: 2015 Update. European Urology. 2015;68(5):868–879. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rouprêt M, Babjuk M, Compérat E, et al. European Association of Urology Guidelines on Upper Urinary Tract Urothelial Carcinoma: 2017 Update. European Urology. 2018;73(1):111–122. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2017.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vemana G, Kim EH, Bhayani SB, Vetter JM, Strope SA. Survival Comparison Between Endoscopic and Surgical Management for Patients With Upper Tract Urothelial Cancer: A Matched Propensity Score Analysis Using Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results-Medicare Data. Urology. 2016;95(C):115–120. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2016.05.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simhan J, Smaldone MC, Egleston BL, et al. Nephron-sparing management vs radical nephroureterectomy for low- or moderate-grade, low-stage upper tract urothelial carcinoma. BJU Int. 2014;114(2):216–220. doi: 10.1111/bju.12341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boffa DJ, Rosen JE, Mallin K, et al. Using the National Cancer Database for Outcomes Research. JAMA Oncol. February 2017:1–7. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.6905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1992;45(6):613–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Austin PC, Stuart EA. Moving towards best practice when using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using the propensity score to estimate causal treatment effects in observational studies. Statist Med. 2015;34(28):3661–3679. doi: 10.1002/sim.6607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cole SR, Hernan MA. Constructing Inverse Probability Weights for Marginal Structural Models. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2008;168(6):656–664. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Austin PC, Stuart EA. The performance of inverse probability of treatment weighting and full matching on the propensity score in the presence of model misspecification when estimating the effect of treatment on survival outcomes. Stat Methods Med Res. 2015;26(4):1654–1670. doi: 10.1177/0962280215584401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. https://www.R-project.org/.

- 14.Baard J, Freund JE, la Rosette de JJMCH, Laguna MP. New technologies for upper tract urothelial carcinoma management. Current Opinion in Urology. 2017;27(2):170–175. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0000000000000373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gadzinski AJ, Roberts WW, Faerber GJ, Wolf JS. Long-Term Outcomes of Nephroureterectomy Versus Endoscopic Management for Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinoma. The Journal of Urology. 2010;183(6):2148–2153. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yakoubi R, Colin P, Seisen T, et al. Radical nephroureterectomy versus endoscopic procedures for the treatment of localised upper tract urothelial carcinoma: A meta-analysis and a systematic review of current evidence from comparative studies. European Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2014;40(12):1629–1634. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2014.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seisen T, Peyronnet B, Dominguez-Escrig JL, et al. Oncologic Outcomes of Kidney-sparing Surgery Versus Radical Nephroureterectomy for Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinoma: A Systematic Review by the EAU Non-muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer Guidelines Panel. European Urology. 2016;70(6):1052–1068. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fang D, Seisen T, Yang K, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of oncological and renal function outcomes obtained after segmental ureterectomy versus radical nephroureterectomy for upper tract urothelial carcinoma. European Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2016;42(11):1625–1635. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2016.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]