Abstract

7 billion tonnes of alkaline materials are produced globally each year as a product or by-product of industrial activity. The aqueous dissolution of these materials creates high pH solutions that dissolves CO2 to store carbon in the form of solid carbonate minerals or dissolved bicarbonate ions. Here we show that these materials have a carbon dioxide storage potential of 2.9–8.5 billion tonnes per year by 2100, and may contribute a substantial proportion of the negative emissions required to limit global temperature change to <2 °C.

The potential of biomass energy carbon capture and storage is unclear. Here the authors estimated the negative emissions potential from highly alkaline materials, by-products and wastes and showed that these materials have a CO2 storage potential of 2.5–7.5 billion tonnes per year by 2100.

Introduction

In addition to substantial cuts in greenhouse gas emissions, humanity may need to remove a large amount of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere to avoid climate change. The ability to remove multiple Gt of CO2 every year is an important feature of integrated assessment models and particularly those that result in global mean surface temperature increases less than 2 °C1–3. By 2100, this cumulative negative emission requirement may be on the order of 100 to 1000 GtCO2 (~1 to 15 GtCO2 yr−1) in 1.5 °C pathways with little or no overshoot and is mostly met by biomass energy carbon capture and storage and afforestation3. There is uncertainty in the potential of most negative emission technologies, which may constrain the rate and extent of their scale-up4,5. Technologies that propose to remove CO2 from the atmosphere by chemical reaction with natural or artificial minerals are included in literature assessments of negative emissions, but have received substantially less attention compared to other proposals6.

Here we consider the potential of negative emissions within existing global industries. Particularly by weathering materials produced from the manufacturing of steel, aluminium, cement, lime, nickel, and from the combustion of coal or biomass. The alkaline materials produced from these activities include blast furnace and steel slag, red mud, cement kiln dust, concrete in building products and demolition waste, ultramafic waste rock and mine tailings and fuel ashes/residue. These materials contain silicate and hydroxide minerals that can dissolve in water and react with CO2 to produce aqueous bicarbonate ions. If these bicarbonate ions were conveyed to the ocean (e.g., in river water), they would contribute to ocean alkalinity, potentially ameliorating some of the impacts of ocean acidification, and remain in solution for >100,000 years7. This enhanced weathering process7,8 (Eqs. (1) and (2)) requires that the bicarbonate ions are stored in the ocean, otherwise additional mineral dissolution would lead to the formation of solid carbonate minerals in which some of the CO2 may be trapped for millions of years (known as mineral carbonation, e.g.9, Eqs. (1 + 3) and Eqs. (2 + 3)).

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

While both mechanisms result in carbon dioxide sequestration, almost twice as much CO2 is removed through enhanced weathering compared to mineral carbonation (the ratio is closer 1.5–1.87), which is highly desirable when material supply is limited. However, there is little research that examines the environmental consequences of increasing ocean alkalinity, and particularly the impact of harmful trace elements that are present in some alkaline materials7. While the residence time of bicarbonate ions in the ocean is effectively permanent, this may be reduced if alkalinity is elevated7. As such, storage of carbon dioxide as a mineral carbonate may be the preferred mechanism, which would also reduce the potential for environmental harm10,11. Both mechanisms have been included in this assessment of storage potential.

Carbon dioxide sequestration has been demonstrated using these materials in elevated temperature and high CO2 pressure (HTP) reactor experiments12,13. However, there is also evidence that atmospheric CO2 is sequestered under ambient conditions14–16. These materials are created by emission intensive industries, and it is therefore reasonable to suggest that the carbon sequestration potential of the by-products should be used to offset some of these emissions. For instance, the steel industry creates approximately 2200 kg CO2 t−1 of steel, which equates to around 12,000 kg CO2 t−1 of by-product slag (Table 1, column a and Supplementary Notes 1, 2, and 3). The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPPC)3 considers that extensive mitigation (e.g., decarbonised energy, carbon capture and storage, energy efficiency improvements) may be able to reduce the emissions intensity to 200–500 kg CO2 t−1 of steel (or ~1000 kg CO2 t−1 slag, column b). Some postulate that the integration of hydrogen into steel making may reduce emissions to <60 kg CO2 t−1 (<300 kg CO2 t−1 slag)17. The carbon dioxide capture potential through mineral carbonation or enhanced weathering of slag is 368–620 kg CO2 t−1. Therefore, only a small proportion of current emissions from most of these industries can be offset by the carbon sequestration in alkaline wastes/by-products. However, by pursuing extensive mitigation together with atmospheric carbon dioxide sequestration in alkaline materials, it may be possible to create industries with net negative emissions, and thus contribute to limiting temperature change to <2 °C.

Table 1.

Carbon production intensities and sequestration potential of highly alkaline materials, by-products and wastes

| Material | 2010 CO2 intensitya | 2050 CO2 intensityb | Carbonation potentialc | Measured carbonationd | Enhanced weathering potentiale | Carbon offset recycling/reusef |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blast furnace slag | 12,000 | 2700–4300 (286–1080)i | 413 ± 13 | 90–230 | 620 ± 19 | ~100. Up to 700 in high substitution specialised cements. <5 as aggregate |

| Basic oxygen furnace slag | 402 ± 17 | 50–540 | 602 ± 25 | |||

| Electric arc furnace slag | 368 ± 10 | 552 ± 15 | ||||

| Ordinary portland cement | 800 | 200–400 (100–200)i | 510 | 300 | 773 | — |

| Cement kiln dust | 6900g | 1700–3500 | 330 ± 12 | 82–260 | 530 ± 21 | ~0 Recycled into kiln |

| Construction and demolition waste | — | — | 77–110 | — | 110–190 | <5 As aggregate |

| Lime | 1000 | 200h | 777 ± 13 | — | 1165 ± 19 | — |

| Ultrabasic mine tailings | 8–250 | — | 40–250 | <50 | 60–377 | — |

| Hard coal ash | 20,000 | (2000–2600)i | 36 ± 6 | 20–30 | 73 ± 10 | ~100. Up to 700 in high substitution specialised cements |

| Lignite ash | 146 ± 28 | 230–264 | 246 ± 52 | |||

| Marine algae biomass ash | 490 | <−16,200 | 31 | — | 348 | |

| Wood/woody biomass ash | −89–815 | 80–380 | −118 to 1766 | |||

| Herbaceous and agricultural biomass ash | −239–520 | −323 to 1505 | ||||

| Animal biomass ash38 | 56–376 | — | 145–724 | |||

| Biomass average | 186 ± 126 | — | 461 ± 260 | |||

| Red mud | 5400 | (1080) | 47 ± 8 | 7–53 | 128 ± 18 < 440 with acid neutralising capacity of liquor | — |

Input data are presented in Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Note 1, all units in kg CO2 t−1

aCalculated by dividing the emissions of the production process by the mass of alkaline material

bPredicted future emission normalised to mass of alkaline material

cMaximum CO2 capture potential by forming carbonate minerals

dCO2 capture measured in experimental work

eMaximum enhanced weathering CO2 capture potential

fCO2 mitigation potential from other uses of material

gSee Supplementary Notes 2 and 3

hBased on an 80% emission reduction target26 (e.g., UK and EU)

iAccounting for aggregate primary energy carbon intensities in RCP2.6 by 2050. Brackets denote 2100 projected

Here we examine the potential of alkaline materials to remove CO2 from the atmosphere by forecasting production to 2100, and show that a large proportion of the future negative emission requirements may be met through weathering or carbonation of these materials.

Results

The potential of alkaline material streams

Manufacturing iron and steel produces a range of alkaline wastes/by-products that are rich in oxide, hydroxide and silicate minerals and glasses, collectively referred to as slag. The physical and chemical properties, and the environmental behaviour, of slag depends on the raw materials, the process of creating iron and steel and the method of disposal. Blast furnace slag is commonly used as secondary aggregate, pozzolan or agricultural lime18–20. However, due to the higher concentrations of oxides and hydroxides, slags from steel production are typically stockpiled21. These sites have highly alkaline leachates with pH > 1021 and can pose environmental issues via extreme pH and potential metal pollution22. CO2 uptake buffers the waters back towards circum-neutral pH, which also limits metal solubility. HTP mineral carbonation experiments have shown 50–75% conversion of slag over 30 min12. However, studies investigating legacy deposits have demonstrated CO2 uptake and carbonate precipitation within the drainage waters and surrounding environments21.

Cement is produced by heating limestone (CaCO3) in a kiln with a source of silicon (clay/shale) to produce metastable calcium silicate minerals (clinker, e.g., Ca2SiO4). The clinker is hydrated during construction to produce mortar and concrete. These materials, together with by-product cement kiln dust, have been successfully carbonated in HTP experiments11,13, during curing under elevated CO2 concentrations23, during the life of the structure24, when mixed into urban soils following demolition14, or within leachate management systems of landfill25.

Like cement, lime is produced by heating limestone in a kiln but is subsequently used in numerous industries (Supplementary Note 4 and Supplementary Table 1 26). Of the lime produced in the United States and European Union, 30–40% is used by the steel industry as a fluxing agent, 14% is used in other industries (sugar refining, glass, paper, precipitated calcium carbonate), 10–20% is used in construction and 16–24% is used for environmental remediation/treatment (flue gas desulphurisation, water treatment, acid mine drainage). Approximately 20% of lime is used in activities that exploit reactions with CO2 (e.g., regenerating NaOH in the Kraft process) or weathering (e.g., agricultural liming). Approximately 14% of the lime is used in activities that do not have an explicit reaction with CO2, but it may be possible to engineer this within the life cycle of the material (e.g., soda lime glass, soil stabilisation).

Residue from coal and biomass combustion (e.g., fly and bottom ash) has been shown to carbonate in HTP experiments27. Due to the small particle size, large surface area and the high concentration of silica, ash is readily reused as a pozzolan or binder substitution in cement production, resulting in a saving of 100–700 kg CO2 t−1 over raw material28, although the extent of substitution is limited by impact on strength. Furthermore, biomass ash has a long history of being spread onto agricultural land as an alternative liming agent29. Under the representative concentration pathway 2.6 (RCP2.6, the pathway most likely to result in <2 °C of warming), the emissions intensity of primary energy is predicted to decrease to 25 kg CO2 GJ−1 by 2050 and −11 kg CO2 GJ−1 by 210030; the lower negative value is a result of biomass energy carbon capture and storage. As such, carbonation or enhanced weathering of ash (up to 1800 kg CO2 t−1) from biomass power generation could represent a non-trivial additional carbon draw-down (Supplementary Note 5 and Supplementary Table 2). The elevated phosphorus or sulphur content could limit the carbonation of some biomass ashes, resulting in an emission of CO2 through the release of acidic waters during weathering.

Aluminium is produced by digesting bauxite ore in a high temperature solution of sodium hydroxide (known as the Bayer process), the products of which are alumina and a waste residue described as red mud. Red mud is composed primarily of iron and aluminium oxide/hydroxide, carbonate or hydroxide calcium (tricalcium aluminate, hydro-calumite) or sodium (sodalite, cancrinite) aluminates31. The residue is typically deposited with unreacted sodium hydroxide solution or dry-stacked. Carbonation of red mud has been demonstrated in HTP and ambient reactions, although only minor uptake was measured (<50 kg CO2 t−1)32,33. The maximum capacity of unsintered/causticised red mud is 128 kg CO2 t−1. The supply of divalent cations through the addition of gypsum, calcium chloride or lime (e.g., during sintering) may further increase the carbonation of the residual solution NaOH and Na-aluminate minerals34 (Supplementary Note 6).

Carbon uptake has been demonstrated in the waste materials and tailing ponds from asbestos16, nickel35 and diamond36 mines, and in HTP experiments37. To estimate the carbon sequestration potential, we have focussed on the waste rock production from nickel and platinum group metal (PGM) mining. We have not accounted for waste from asbestos production, the future generation of which may be limited (Supplementary Note 7).

Alkaline material production forecast

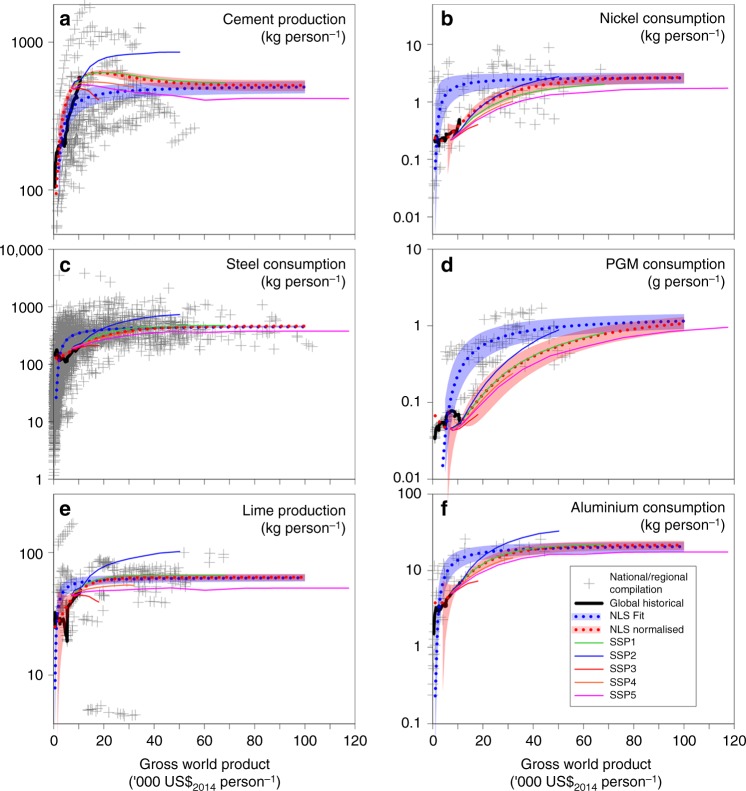

By combining material economic saturation trends (see, e.g., van Ruijven et al.38) with forecasts of global economic development, consumption, population and biomass/coal primary energy from shared socio-economic pathways (SSPs) and associated aggregated RCPs39, it is possible to estimate future production of alkaline materials. We focus specifically on the contemporary and future production of alkaline materials, but there may also be tens of Gt of material stockpiled from historical production40,41. Figure 1 shows annual per capita production/consumption of cement, steel, PGM and nickel, and lime as a function of gross domestic product (GDP) or gross world product (GWP). Nonlinear least squares regression through national and global data were used to predict future production (a list of nations is included in the Supplementary Note 8). Consumption in the SSPs has been normalised to 2005 and used to derive relative changes to the baseline.

Fig. 1.

Consumption/production global saturation estimates for alkaline materials. a Cement, b nickel, c steel, d platinum group metal (PGM), e lime and f aluminium as a function of gross world product (GWP). The diagrams show a nonlinear least squares regression through compiled national data (blue dotted, the shading represents ±the standard error). The saturation value from this was fixed in an additional regression using global data relative to 2014 consumption (red dotted). Using the global fit as a baseline, the relative consumption projections for the shared socio-economic pathways (SSPs) were derived by normalising absolute changes in consumption. Production has been used for lime and cement that have a relatively small international trade market (<5%), otherwise apparent consumption has been plotted using national (slag) or regional (aluminium, PGM, nickel) data

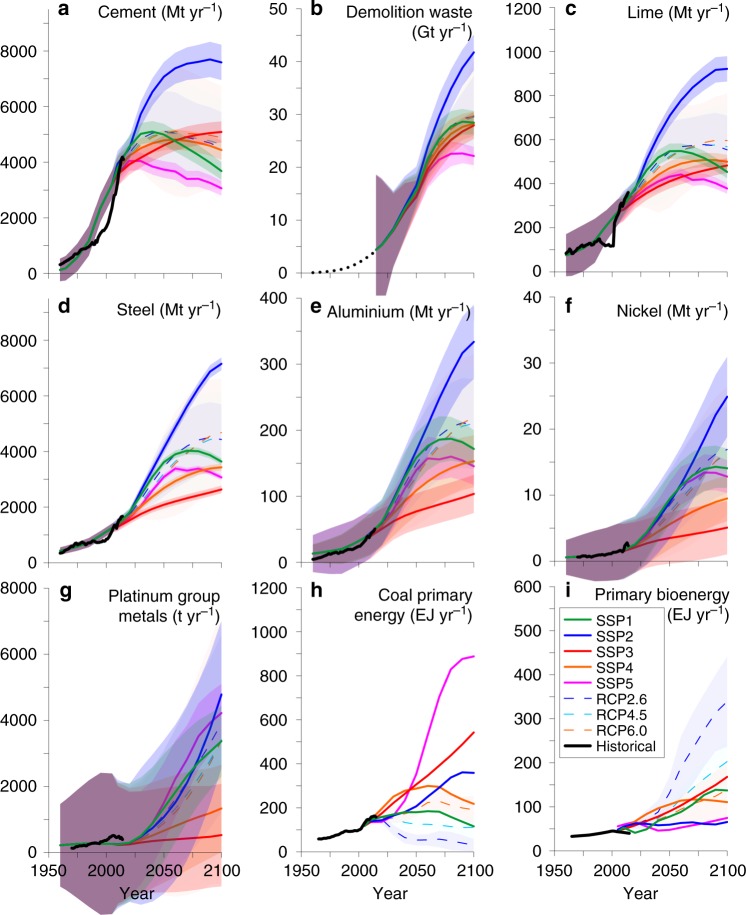

Maximum (SSP2) 2100 production estimates for cement, steel, aluminium and lime are 7.5 ± 0.4 Gt yr−1, 7.1 ± 0.1 Gt yr−1, 334 ± 34 Mt yr−1 and 900 ± 35 Mt yr−1 respectively (Fig. 2). Approximately 8–15% of the cement production is kiln dust which equates to between 245 Mt yr−1 and 1.1 Gt yr−1 by 2100. Approximately 300 Mt of concrete demolition waste are currently produced annually from a concrete stock of around 315 Gt42. Our model predicts production of demolition waste may increase to 20–40 Gt yr−1 by 2100. Steel and blast furnace slag production may increase to 2.2 and 0.7 Gt yr−1 respectively by the end of the century. Red mud from aluminium production may increase from 150 Mt yr−1 currently to 500–1100 Mt yr−1 by 2100. Primary energy from coal combustion in the SSP baseline scenarios is anticipated to vary between recent production 120 EJ yr−1 to >880 EJ yr−1. The RCP compilations largely predict decreases in coal use to <60 EJ yr−1 for 2.6. Assuming a coal mix that changes from current levels (10% lignite, and 90% hard coal of bituminous/anthracite, with ash contents ~10%) to zero lignite by 2100, the total ash production varies between 130 Mt yr−1 and 4.2 Gt yr−1. An inverse relationship is predicted for biomass energy production, with ash production ranging from 300 Mt yr−1 (SSP5) to 1.2 Gt yr−1 in the RCP2.6 compilation. Up to 3.5 Gt yr−1 of ultrabasic mine tailings (SSP2) may be produced by 2100 because of extracting ~25 Mt yr−1 of nickel and ~5 kt yr−1 of platinum group elements (see Supplementary Figs. 1–5 for material-specific production forecasts and associated carbonation potential).

Fig. 2.

Production estimates for alkaline materials. a Cement, b demolition waste, c lime, d steel, e aluminium, f nickel, g platinum group metals, h coal primary energy and i primary bioenergy. Historical material production58 and energy use49 are also shown. Production forecasts were generated by combining a gross world product-per capita production saturation model, with projections of future economic growth, relative consumption, population and energy production

Discussion

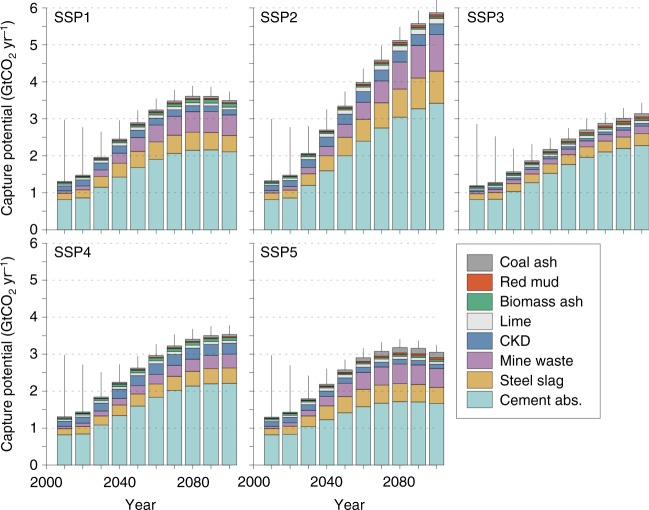

The results suggest that the global CO2 carbonation potential may increase from 1 GtCO2 yr−1, which is consistent with previous estimates based on current production40, to between 2.3 and 3.3 GtCO2 y−1 in 2050 and 2.9 and 5.9 GtCO2 yr−1 by 2100 (Fig. 3). Trends in material consumption (high in SSP2, status in SSP5) drive the larger difference between these scenarios, with relative changes in GDP or population between other scenarios diminishing the difference in CO2 capture potentials. Global CO2 emissions in the baseline SSP scenarios in 2100 range from 24 GtCO2 yr−1 (SSP1) to 126 GtCO2 yr−1 (SSP5). Carbonating alkaline waste materials may mitigate between 5 and 12% of these baseline emissions. The lower emission RCPs predict CO2 emissions to reach zero later this century and become net negative by up to 16 GtCO2 yr−1 (RCP2.6) in 21003. As such, the carbonation of alkaline materials using atmospheric CO2 could contribute ~18 and 37% of the negative emission requirements in RCP2.6. The enhanced weathering potential of alkaline materials (see Supplementary Fig. 6) ranges between 2.6 and 3.8 GtCO2 yr−1 in 2050, and increases to between 4.3 (SSP5) and 8.5 (SSP2) GtCO2 yr−1 by 2100. This is comparable to estimated potentials of other methods of removing CO2 from the atmosphere. For instance, a recent synthesis report from the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine2 suggest safe global scalable levels of sequestration to be 1–1.5 GtCO2 yr−1 for afforestation or forest management, 3 GtCO2 yr−1 for soil carbon management and 3.5–5.2 GtCO2 yr−1 for biomass energy carbon capture and storage. However, the land requirements of CO2 capture using alkaline materials are considerably less.

Fig. 3.

Forecast of CO2 capture potential through carbonation of alkaline materials to 2100 for the baseline shared socio-economic pathways (SSPs). The error bars represent the standard error for the range of concentration pathways in the SSPs (n = 4 for SSPs 1 and 3, and n = 5 for SSPs 2, 4 and 5) together with uncertainties of material production and consumption, and chemistry

These projections represent a theoretical maximum potential, which, in practice, would be difficult to realise. Research investigating carbon uptake using these materials has primarily focused on HTP reactor experiments11–13,27,32,37, which are typically far from optimised. Considerably more research is required to assess the potential for optimising CO2 capture at ambient conditions.

Production data for many of these materials are typically not reported, and inventory assessments of current stockpiles are unlikely to be publicly available. As such, it is only possible to estimate production, as we have done, through proxy information. A more robust accounting mechanism is required to accurately assess the potential of alkaline materials.

Furthermore, there is no national or international mechanism for accounting for the value of CO2 capture in waste. While this may be relatively trivial for carbonating materials emanating from a production site, it is more complicated for cement and lime where the latent carbon sequestration potential is only realised after many years of service life.

The economic cost of capturing CO2 using alkaline materials could be relatively low as most are available as wastes or low-value by-products, and typically in particle sizes that facilitate rapid reaction. There may be additional processing costs (particularly in supplying CO2 or water to the reaction site), which may lower the efficiency of the proposals. These costs should be explored further and included within integrative assessment models to consider the wider carbon balances of reacting atmospheric CO2 alkaline wastes.

Before deployment at scale it is imperative that the environmental and social consequences of these activities are explored. Carbonate formation in alkaline waste materials has long been associated with lowering their environmental burden22, whereas ash and slag have been used positively as replacement lime for agriculture. However, these materials are heterogeneous, and individual production sites will require unique and ongoing assessments.

Exploiting opportunities in existing industries for atmospheric CO2 sequestration may contribute significantly to preventing climate change, by storing carbon permanently in either mineral carbonates or as dissolved bicarbonate in the ocean. It would be unwise to explore this potential at the expense of extensive emissions reduction. However, meeting the material demands of a growing global population will present an opportunity for low-cost atmospheric carbon dioxide sequestration that would be equally myopic to ignore.

Methods

Production forecast model

A model that relates national or regional per capita material production (for cement and lime) or consumption (for aluminium, steel, platinum group metals, and nickel) (P) to per capita GDP (national or regional data, see Supplementary Fig. 7 and Note 2)38 was regressed through historical data using nonlinear least squares (Eq. (4)).

| 4 |

where a and b are regression constants. The values returned for a and b for each material are included in the Supplementary Table 3 with their standard error. The derived saturation value, a, was used in a further regression through global data normalised to 2014 production and GDP (Eq. (5)).

| 5 |

where PREF is the global per capita consumption at a given reference year (2014), ΔGWP is the deviation of the per capita GWP from the reference year; and m and r are regression constants, for which m was fixed and r varied (a sensitivity analysis for variations in m was performed to minimise the standard error for r). This formed the baseline which was modified with relative normalised consumption intensities (Ct/C2005) for each SSP and RCP derivative. The per capita consumption model was combined with GWP capita−1 and population forecasts (Pop) associated with the SSPs, to derive production forecasts (T) for cement, steel, aluminium, lime, PGM and nickel (Eqs. (6) and (7)).

| 6 |

| 7 |

Beyond the forecast change in economic consumption, we have not considered the penetration of recycling into metals production. Recycling would reduce the production of slag and remove completely the production of red mud and mine tailings. However, the proportion of material that may be recycled is limited (e.g., 69% for steel and 65% for aluminium43,44), particularly for developing economies yet to reach saturation. As such, we may overestimate the contribution of CO2 removal using slag, mine tailings or red mud. Cement, cement kiln dust, lime and ash have no capacity to be recycled as the original materials.

For every tonne of clinker, 115 ± 17 kg of cement kiln dust is produced as a by-product in kilns. While the latent capacity of CO2 uptake in cement could be partially realised through elevated CO2 curing (see, e.g., ref. 23), we have only modelled carbonation/weathering through reabsorption during a 50-year service life (based on the method in ref. 24 and carbonation/weathering following demolition; see refs. 11,14, Supplementary Note 3, Supplementary Tables 4 and 5). Of the lime production, 20% was assumed available for reaction with CO2 (see Supplementary Note 4). The ratio of pig iron to steel production (0.724 ± 0.002) was found using linear regression of 1960–2014 data, negating the need to explicitly model pig iron displacement from scrap recycling, assuming the scrap ratio remains unchanged. All steel and blast furnace slags were considered available for reaction with CO2. While a substantial proportion of blast furnace slag is recycled as aggregate or for clinker replacement18, we assume that the value (cost and carbon) is greater for reaction with atmospheric CO2 than for clinker replacement (e.g., Table 1). If the silicon was extracted from the slag prior to carbonation, recycling and CO2 capture may not be mutually exclusive. Between 2006 and 2014, there was 185 ± 5 kg of blast furnace slag and 117 ± 5 kg of steel slag produced for every tonne of crude steel43. Between 1967 and 2014, 3.5 ± 0.04 tonnes of red mud were produced for every tonne of aluminium (see Supplementary Note 6)45. Approximately 60% of nickel reserves are contained within ultrabasic laterite deposits (containing 1.2 ± 0.4% s.d. Ni46,47), the remaining proportion is associated with nickel sulphide deposits (containing 0.4 ± 0.4% s.d. Ni47), the ratio of which we have assumed for future production. Approximately 81 ± 24 and 234 ± 253 tonnes of ultrabasic gangue (the non-commercial proportion of the ore) are produced for every tonne of nickel from laterite and sulfidic deposits respectively (Supplementary Note 7)47. Approximately 84% of base reserve PGM deposits are contained in ultramafic rock (containing 4.7 ± 0.7 g Pt and Pd t−1 48), which has been used in this model. The remaining reserves are contained in nickel sulphide deposits and have not been considered to avoid double counting with the above. For every kg of PGM produced, 212 ± 31 tonnes of ore are processed.

Projections of future biomass and coal primary energy generation were taken from refs. 49, and combined with average higher heating values and ash contents (see Supplementary Note 5) to estimate future production of ash (Eq. (8)).

| 8 |

where E is the primary energy generation, HHV is the higher heating value and A is ash content. For all materials, the production forecast is multiplied by the carbonation or enhanced weathering potential (Table 1).

The CO2 sequestration capacity of alkaline materials

The carbonation (Cpot, Eqs. (1 + 3) and Eqs. (2 + 3), expressed in kg CO2 t−1) or enhanced weathering potential (Epot, Eqs. (1) and (2)) for each material (example minerals are presented in Supplementary Table 6) was derived using the bulk elemental composition of iron and steel slag50, cement, cement kiln dust13, demolition waste40, lime51, coal ash52,53, biomass ash54, red mud31 and PGM55 and Ni56 tailings in the modified Steinour formula57 (Eqs. (9) and (10)).

| 9 |

| 10 |

where CaO, MgO, SO3, P2O5, Na2O and K2O are the elemental concentrations of Ca, Mg, S, P, Na and K, expressed as oxides (Supplementary Table 7), Mx is the molecular mass of those oxides; coefficients α, β, γ, δ, ε, and θ consider the relative contribution of each oxide (Supplementary Figs 8 and 9); and η is molar ratio of CO2 to divalent cation sequestered during enhanced weathering. Equations (1) and (2) imply η = 2; however, due to buffering in the carbonate system, the value is between 1.4 and 1.7 for typical seawater chemistry, pCO2 and temperature8. We have used η = 1.5, which is a conservative global average. The values of carbonation and enhanced weathering potential of alkaline materials is shown in Table 1, columns c and e, respectively.

Equations (9) and (10) imply that the potential is reduced by the presence of sulphur and phosphorus within the material. These elements are either bound to cations within the material, the dissolution reactions of which have no implicit reaction with CO2 (Eqs. (11) and (12)), or they are present as, or may become, acid compounds which would impact the carbonate system to produce CO2 (Eqs. (13) and (14)).

| 11 |

| 12 |

| 13 |

| 14 |

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

P.R. is funded by the UK’s Greenhouse Gas Removal Programme, supported by the Natural Environment Research Council, the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, the Economic & Social Research Council and the Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy under grant no. NE/P019943/1.

Author contributions

P.R. designed the study, undertook the calculations and wrote the manuscript.

Data availability

Data generated as part of this study have been made available to download as supplementary data (Supplementary Data 1–9).

Code availability

Coding data not applicable for this study.

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Footnotes

Journal peer review information: Nature Communications thanks Georgios N. Kalantzopoulos, Gregory M. Dipple and the other anonymous reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-019-09475-5.

References

- 1.Fuss S, et al. Betting on negative emissions. Nat. Clim. Change. 2014;4:850. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2392. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Negative Emissions Technologies and Reliable Sequestration: A Research Agenda (The National Academies Press, Washington, 2018). [PubMed]

- 3.IPCC. Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Incheon, 2018).

- 4.Vaughan NE, et al. Evaluating the use of biomass energy with carbon capture and storage in low emission scenarios. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018;13:044014. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/aaaa02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fajardy M, Mac Dowell N. Can BECCS deliver sustainable and resource efficient negative emissions? Energy Environ. Sci. 2017;10:1389–1426. doi: 10.1039/C7EE00465F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Minx JC, et al. Negative emissions—Part 1: research landscape and synthesis. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018;13:063001. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/aabf9b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Renforth P, Henderson G. Assessing ocean alkalinity for carbon sequestration. Rev. Geophys. 2017;55:636–674. doi: 10.1002/2016RG000533. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hartmann J, et al. Enhanced chemical weathering as a geoengineering strategy to reduce atmospheric carbon dioxide, supply nutrients, and mitigate ocean acidification. Rev. Geophys. 2013;51:113–149. doi: 10.1002/rog.20004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lackner KS, Wendt CH, Butt DP, Joyce EL, Sharp DH. Carbon dioxide disposal in carbonate minerals. Energy. 1995;20:1153–1170. doi: 10.1016/0360-5442(95)00071-N. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mayes WM, et al. Atmospheric CO2 sequestration in iron and steel slag: Consett, County Durham, United Kingdom. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018;52:7892–7900. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b01883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fernández Bertos M, Simons SJR, Hills CD, Carey PJ. A review of accelerated carbonation technology in the treatment of cement-based materials and sequestration of CO2. J. Hazard. Mater. 2004;112:193–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2004.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huijgen WJJ, Comans RNJ. Mineral CO2 sequestration by steel slag carbonation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005;39:9676–9682. doi: 10.1021/es050795f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huntzinger DN, Gierke JS, Kawatra SK, Eisele TC, Sutter LL. Carbon dioxide sequestration in cement kiln dust through mineral carbonation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009;43:1986–1992. doi: 10.1021/es802910z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Washbourne CL, Renforth P, Manning DAC. Investigating carbonate formation in urban soils as a method for capture and storage of atmospheric carbon. Sci. Total Environ. 2012;431:166–175. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Renforth P, Manning DAC, Lopez-Capel E. Carbonate precipitation in artificial soils as a sink for atmospheric carbon dioxide. Appl. Geochem. 2009;24:1757–1764. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeochem.2009.05.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson SA, et al. Carbon dioxide fixation within mine wastes of ultramafic-hosted ore deposits: examples from the Clinton Creek and Cassiar Chrysotile Deposits, Canada. Econ. Geol. 2009;104:95–112. doi: 10.2113/gsecongeo.104.1.95. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vogl V, Åhman M, Nilsson LJ. Assessment of hydrogen direct reduction for fossil-free steelmaking. J. Clean. Prod. 2018;203:736–745. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.08.279. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roy DM, ldorn GM. Hydration, structure, and properties of blast furnace slag cements, mortars, and concrete. J. Proc. 1982;79:444–457. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahmedzade P, Sengoz B. Evaluation of steel slag coarse aggregate in hot mix asphalt concrete. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009;165:300–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.09.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davis F, Collier B, Carter O. Blast-furnace slag as agricultural liming material. Commer. Fertil. 1950;80:48–49. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yi H, et al. An overview of utilization of steel slag. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2012;16:791–801. doi: 10.1016/j.proenv.2012.10.108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mayes WM, Younger PL, Aumônier J. Hydrogeochemistry of alkaline steel slag leachates in the UK. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2008;195:35–50. doi: 10.1007/s11270-008-9725-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Young J, Berger R, Breese J. Accelerated curing of compacted calcium silicate mortars on exposure to CO2. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1974;57:394–397. doi: 10.1111/j.1151-2916.1974.tb11420.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xi F, et al. Substantial global carbon uptake by cement carbonation. Nat. Geosci. 2016;9:880. doi: 10.1038/ngeo2840. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fleming IR, Rowe RK, Cullimore DR. Field observations of clogging in a landfill leachate collection system. Can. Geotech. J. 1999;36:685–707. doi: 10.1139/t99-036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.EuLA. A Competitive and Efficient Lime Industry. Prepared by Ecofys (European Lime Association, 2014). https://www.eula.eu/documents/competitive-and-efficient-lime-industry-cornerstone-sustainable-europe-lime-roadmap-1.

- 27.Montes-Hernandez G, Pérez-López R, Renard F, Nieto JM, Charlet L. Mineral sequestration of CO2 by aqueous carbonation of coal combustion fly-ash. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009;161:1347–1354. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.04.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller SA, Horvath A, Monteiro PJM, Ostertag CP. Greenhouse gas emissions from concrete can be reduced by using mix proportions, geometric aspects, and age as design factors. Environ. Res. Lett. 2015;10:114017. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/10/11/114017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.James AK, Thring RW, Helle S, Ghuman HS. Ash management review—applications of biomass bottom ash. Energies. 2012;5:3856–3873. doi: 10.3390/en5103856. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Vuuren DP, et al. The representative concentration pathways: an overview. Clim. Change. 2011;109:5. doi: 10.1007/s10584-011-0148-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gräfe M, Power G, Klauber C. Bauxite residue issues: III. Alkalinity and associated chemistry. Hydrometallurgy. 2011;108:60–79. doi: 10.1016/j.hydromet.2011.02.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yadav VS, et al. Sequestration of carbon dioxide (CO2) using red mud. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010;176:1044–1050. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.11.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bonenfant D, et al. CO2 sequestration by aqueous red mud carbonation at ambient pressure and temperature. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2008;47:7617–7622. doi: 10.1021/ie7017228. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Renforth P, et al. Contaminant mobility and carbon sequestration downstream of the Ajka (Hungary) red mud spill: the effects of gypsum dosing. Spec. Sect. Rev. Trace Met. Pollut. China. 2012;421–422:253–259. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pronost J, et al. Carbon sequestration kinetic and storage capacity of ultramafic mining waste. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011;45:9413–9420. doi: 10.1021/es203063a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilson SA, Raudsepp M, Dipple GM. Quantifying carbon fixation in trace minerals from processed kimberlite: a comparative study of quantitative methods using X-ray powder diffraction data with applications to the Diavik Diamond Mine, Northwest Territories, Canada. Appl. Geochem. 2009;24:2312–2331. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeochem.2009.09.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bobicki ER, Liu Q, Xu Z, Zeng H. Carbon capture and storage using alkaline industrial wastes. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2012;38:302–320. doi: 10.1016/j.pecs.2011.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Ruijven BJ, et al. Long-term model-based projections of energy use and CO2 emissions from the global steel and cement industries. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016;112:15–36. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2016.04.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Riahi K, et al. The shared socioeconomic pathways and their energy, land use, and greenhouse gas emissions implications: an overview. Glob. Environ. Change. 2017;42:153–168. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.05.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Renforth P, Washbourne CL, Taylder J, Manning DAC. Silicate production and availability for mineral carbonation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011;45:2035–2041. doi: 10.1021/es103241w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Picot JC, Cassard D, Maldan F, Greffié C, Bodénan F. Worldwide potential for ex-situ mineral carbonation. Energy Procedia. 2011;4:2971–2977. doi: 10.1016/j.egypro.2011.02.206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krausmann F, et al. Global socioeconomic material stocks rise 23-fold over the 20th century and require half of annual resource use. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:1880. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1613773114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oss, H. G. v. Slag – Iron and Steel Mineral Commodity Summaries (U.S. Department of the Interior and U.S. Geological Survey, 2016). https://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/iron_&_steel_slag/.

- 44.Gutowski, T. G., Sahni, S., Allwood, J. M., Ashby, M. F. & Worrell, E. The energy required to produce materials: constraints on energy-intensity improvements, parameters of demand. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci.371, 20120003 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Bertram M, et al. A regionally-linked, dynamic material flow modelling tool for rolled, extruded and cast aluminium products. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017;125:48–69. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2017.05.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Berger, V. I., Singer, D. A., Bliss, J. D. & Moring, B. C. Ni-Co Laterite Deposits of the World: Database and Grade and Tonnage Models (US Department of the Interior, Geological Survey, 2011). https://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2011/1058/.

- 47.Mudd GM, Jowitt SM. A detailed assessment of global nickel resource trends and endowments. Econ. Geol. 2014;109:1813–1841. doi: 10.2113/econgeo.109.7.1813. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wilburn DR, Bleiwas DI. Platinum-group metals—world supply and demand. US Geol. Surv. Open File Rep. 2004;1224:2004–1224. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smil, V. Energy Transitions: Global and National Perspectives (ABC-CLIO, Santa Barbara, 2016).

- 50.Proctor DM, et al. Physical and chemical characteristics of blast furnace, basic oxygen furnace, and electric arc furnace steel industry slags. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2000;34:1576–1582. doi: 10.1021/es9906002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Oates, T. Lime and limestone. in Kirk‐Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology (ed. Kirk-Othmer) 1–53 (American Cancer Society, New York, NY, 2002). 10.1002/0471238961.1209130507212019.a01.pub2.

- 52.Selvig, W. A. & Gibson, F. H. Analyses of Ash from Coals of the United States (U.S. G.P.O., Washington, 1945).

- 53.Dai S, et al. Geochemistry of trace elements in Chinese coals: a review of abundances, genetic types, impacts on human health, and industrial utilization. Miner. Trace Elem. Coal. 2012;94:3–21. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vassilev SV, Baxter D, Andersen LK, Vassileva CG. An overview of the composition and application of biomass ash. Part 1. Phase–mineral and chemical composition and classification. Fuel. 2013;105:40–76. doi: 10.1016/j.fuel.2012.09.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vogeli J, Reid DL, Becker M, Broadhurst J, Franzidis JP. Investigation of the potential for mineral carbonation of PGM tailings in South Africa. Miner. Eng. 2011;24:1348–1356. doi: 10.1016/j.mineng.2011.07.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Marsh, E., Anderson, E., & Gray, F. Nickel–cobalt laterites—a deposit model. Chapter H of Mineral Deposit Models for Resource Assessment: U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2010–5070–H (2013). https://pubs.er.usgs.gov/publication/sir20105070H.

- 57.Gunning PJ, Hills CD, Carey PJ. Accelerated carbonation treatment of industrial wastes. Waste Manag. 2010;30:1081–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.USGS. USGS Minerals Yearbook (U.S. Department of the Interior and U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, VA, United States, 2016).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

Data generated as part of this study have been made available to download as supplementary data (Supplementary Data 1–9).

Coding data not applicable for this study.