Abstract

The extracellular heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) is known to participate in cell migration and invasion. Recently, we have shown that cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) are involved in the binding and anchoring of extracellular Hsp90 to the plasma membrane, but the biological relevance of this finding was unclear. Here, we demonstrated that the digestion of heparan sulfate (HS) moieties of HSPGs with a heparinase I/III blend and the metabolic inhibition of the sulfation of HS chains by sodium chlorate considerably impair the migration and invasion of human glioblastoma A-172 and fibrosarcoma HT1080 cells stimulated by extracellular native Hsp90. Heparin, a polysaccharide closely related to HS, also reduced the Hsp90-stimulated migration and invasion of cells. Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate, an intracellular inducer of cell motility bypassing the ligand activation of receptors, restored the basal migration of heparinase- and chlorate-treated cells almost to the control level, suggesting that the cell motility machinery was insignificantly affected in cells with degraded and undersulfated HS chains. On the other hand, the downstream phosphorylation of AKT in response to extracellular Hsp90 was substantially impaired in heparinase- and chlorate-treated cells as compared to untreated cells. Taken together, our results demonstrated for the first time that cell surface HSPGs play an important role in the migration and invasion of cancer cells stimulated by extracellular Hsp90 and that plasma membrane-associated HSPGs are required for the efficient transmission of signal from extracellular Hsp90 into the cell.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s12192-018-0955-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Cell surface HSPGs, Extracellular Hsp90, Hsp90-stimulated cell migration, Hsp90-stimulated cell invasion

Introduction

The heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) is one of the most abundant and ubiquitously expressed proteins that constitutes approximately 1–2% of the total cell protein content (Li and Buchner 2013). There are two major cytoplasmic isoforms of Hsp90, Hsp90α (the inducible form) and Hsp90β (the constitutive form), that share a high-sequence homology but show differences in biochemical properties, expression, and function (Li and Buchner 2013; Sreedhar et al. 2004). Hsp90 acts inside cells as a chaperone that regulates the folding, maturation, transport, and degradation of a diverse set of client proteins, in particular, signaling molecules, steroid receptors, and transcription factors (Li and Buchner 2013; Sreedhar et al. 2004). The protein is localized not only inside the cell but also in the extracellular space (extracellular soluble Hsp90) and at the cell plasma membrane (extracellular membrane-associated Hsp90). Hsp90 is secreted by many types of cancer cells (Becker et al. 2004; Chen et al. 2010; Cheng et al. 2008; Li et al. 2007; McCready et al. 2010; Suzuki and Kulkarni 2010; Wang et al. 2009) and is found on the surface of numerous cells (Cheng et al. 2008; Crowe et al. 2017; Sidera et al. 2008). Cell stressors such as oxidative stress, heat shock, and hypoxia, as well as growth factors, stimulate the translocation of Hsp90 to the plasma membrane and/or its secretion (Cheng et al. 2008; Clayton et al. 2005; Crowe et al. 2017; Gopal et al. 2011; Li et al. 2007; Song et al. 2010; Wang et al. 2009). The level of cell surface expression and secretion of Hsp90 in tumor cells is elevated, which correlates with the metastatic potential of cells (Becker et al. 2004; Hance et al. 2012). Cell surface Hsp90 is actively internalized by cancer cells (Crowe et al. 2017). Extracellular Hsp90 promotes cell migration (Becker et al. 2004; Cheng et al. 2011; Gopal et al. 2011; Li et al. 2007; McCready et al. 2010; Sidera et al. 2004; Sidera et al. 2008) and skin wound healing (Cheng et al. 2011; Li et al. 2007) and stimulates the invasion and metastatic activities of cancer cells (Becker et al. 2004; Gopal et al. 2011; McCready et al. 2010; Sidera et al. 2008). There are several mechanisms of action of extracellular Hsp90 in cell motility. Hsp90 can function as a pro-motility factor by binding to a growing number of transmembrane cell surface receptors and inducing the signaling in normal and cancer cells (Basu et al. 2001; Chen et al. 2010; Cheng et al. 2008; El Hamidieh et al. 2012; Lei et al. 2004; Sidera et al. 2008). Extracellular Hsp90 cooperates with the low-density lipoprotein-related protein (LRP1), activating various signaling pathways (Basu et al. 2001; Chen et al. 2010, 2013; Cheng et al. 2008). Hsp90 also binds to HER2, inducing EGFR3/HER2 dimerization and EGFR signaling (Sidera et al. 2008). Extracellular Hsp90 participates in the ligand-independent EphA2 activation (Gopal et al. 2011) and TLR4-mediated activation of EGFR (Thuringer et al. 2011). The protein also regulates the signaling of integrin by modulating its expression and interaction with Src to form focal adhesions (Chen et al. 2010; Tsutsumi et al. 2008). Besides functioning as a pro-motility ligand that interacts with different cell surface receptors, extracellular Hsp90 can also increase the stability and activity of some surface-bound or secreted proteins, such as matrix metalloproteinases and extracellular matrix proteins, thus promoting cell motility and invasion (Correia et al. 2013; Hunter et al. 2014; Lagarrigue et al. 2010).

Heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) are abundant cell-surface and extracellular matrix glycoproteins that comprise a core protein to which heparan sulfate (HS) glycosaminoglycan chains are covalently attached (Gallagher 2015; Sarrazin et al. 2011). On the surface of most mammalian cells, the representatives of two major families of HSPGs, glypicans and syndecans, are localized (Gallagher 2015; Sarrazin et al. 2011). HSPGs are involved in many biological processes, including cell growth and division, development, embryogenesis, cell adhesion and motility, and cell signaling (Gallagher 2015; Mitsou et al. 2017; Sarrazin et al. 2011). Due to the structural diversity, the HS moieties of cell surface HSPGs are able to interact with a wide range of growth factors, morphogenic proteins, and cytokines, functioning as “low-affinity” co-receptors to provide more efficient ligand interaction with “higher-affinity” receptors and signal transduction (Gallagher 2015; Lindahl and Li 2009; Sarrazin et al. 2011). Recently, we have shown that extracellular Hsp90 interacts with the HS moieties of cell surface HSPGs (Snigireva et al. 2015). The involvement of HSPGs in the biological activity of extracellular Hsp90 remains uncertain and warrants further investigation. Here, we demonstrated for the first time that cell surface HSPGs potentiate the Hsp90-generated signaling in human glioblastoma A-172 and fibrosarcoma HT1080 cells and thereby participate in the Hsp90-stimulated cell migration and invasion.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and reagents

Human glioblastoma A-172 and fibrosarcoma HT1080 cells were from the Cell Culture Collection of Vertebrates (St. Petersburg, Russia). The cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (DMEM-FBS) and antibiotics in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. FBS and DMEM were purchased from GE Healthcare. Transwell inserts with a polycarbonate membrane (8 μm) were from Corning. Basement membrane collagen IV was from Trevigen Inc. Polyvinylidene difluoride membrane was from Merck-Millipore. Rabbit phospho-AKT1/2/3 (Ser 473) antibodies (sc-4985-R) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Mouse monoclonal antibodies specific for Hsp90α (ab59459) and Hsp90β (ab53497) were from Abcam, heparin/HS (MAB2040) was from Merck-Millipore, LRP1 (MCA1965) was from Bio-Rad, and β-actin (sc-47,778) was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Secondary HRP-conjugated antibodies were from Bio-Rad. Alexa 488-labeled secondary conjugates were purchased from Jacksons ImmunoResearch Laboratories. Cell culture plastic labware was from Corning. All other chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich.

Purification of native Hsp90

Native mouse, swine, and bovine Hsp90s were purified from mouse, swine, and bovine brains as described earlier (Skarga et al. 2009). The cytotoxicity and аntiproliferative аctivity of native Hsp90 were determined using the MTT assay as described (Lisov et al. 2015).

Wound-healing assay

In the experiments on enzymatic degradation of HS moieties, cells were grown in 35-mm culture dishes for 24 h at 37 °C to form a “fresh” confluent monolayer and then incubated for 1–2 h at 37 °C with a heparinase I/III blend from Flavobacterium heparinum (Sigma-Aldrich) diluted in DMEM-FBS (0.03 IU/ml). To inhibit the sulfation of HS chains, the cells were grown in 35-mm culture dishes in DMEM-FBS supplemented with 30 mM sodium chlorate for 24 h at 37 °C to form a “fresh” confluent monolayer. A “scratch” was created by scraping the monolayer of heparinase- and chlorate-treated cells in a straight line with a pipet tip. The cells were washed with DMEM and cultured in DMEM containing 0.2% BSA (DMEM-BSA) for 6 h at 37 °C (basal migration) or in the presence of native Hsp90 (50 μg/ml) (Hsp90-stimulated migration). In each experiment, monolayers of control untreated cells were also wounded, and cells were stimulated by native Hsp90 in the same way. Pictures were taken immediately after cell wounding (0 h) and 6 h after cell wounding. The images were captured by a CCD camera (DM 2500, Leica), and wound areas were calculated using the Leica Application Suite v3.0. software. The basal migration of heparinase/chlorate-treated cells was determined by comparing the wound areas of control and heparinase/chlorate-treated cells and expressed in percent (wound area of control untreated cells was taken as 100%). To calculate the degree of stimulation of cell migration/invasion by extracellular Hsp90, the wound area of Hsp90-stimulated cells was subtracted from that of unstimulated cells (basal migration), and the residual value was expressed in percent relative to the wound area of unstimulated cells (basal migration). Thus, the Hsp90-stimulated migration of control, heparinase-, and chlorate-treated cells was calculated relative to the respective basal migration of control, heparinase-, and chlorate-treated cells. To compare the Hsp90-stimulated migration of control and heparinase/chlorate-treated cells, the stimulation of migration of control cells was taken as 100%. To analyze the effect of heparin, chondroitin sulfate A, or dermatan sulfate on the basal and Hsp90-stimulated cell migration, the wound-healing assay was performed in the presence of sulfated glycosaminoglycans (50 μg/ml). To determine whether cells with degraded/undersulfated HS chains retain the capacity to migrate after appropriate stimulation, heparinase- and chlorate-treated cells were induced with PMA diluted to a concentration of 100 nM in DMEM containing 2% FBS, and the migration of cells was determined in the wound-healing assay.

Transwell migration/invasion assays

In the experiments on enzymatic degradation of HS moieties, cells were grown in 35-mm culture dishes for 18 h to reach 80–90% confluence. Then cells were serum starved by incubation in DMEM-BSA for 24 h at 37 °C, detached from culture dishes by incubation for 5 min at 37 °C with 0.05% Na-EDTA, suspended in DMEM-BSA, and treated for 1–2 h at 37 °C with a heparinase I/III blend (0.03 IU/ml). In the experiments on undersulfation of HS chains, cells were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h in DMEM-FBS supplemented with 30 mM sodium chlorate and for 24 h in DMEM-BSA containing 30 mM sodium chlorate, followed by the detachment of cells from culture dishes as described above. The suspensions of heparinase- and chlorate-treated cells were washed with DMEM, suspended in DMEM-BSA in the presence and absence of native Hsp90 (50 μg/ml) to stimulate cell migration/invasion, and plated into the top chambers of transwell inserts. In the transwell migration assay, cells were allowed to migrate through a membrane for 6 h toward DMEM supplemented with 5% FBS in the bottom chambers to form a chemotactic gradient. In the transwell invasion assay, polycarbonate membranes of inserts were preliminarily coated with collagen IV (400 μg/ml) according to the manufacturer‘s recommendations, and cells migrated for 24 h toward the chemotactic gradient. Optimal migration times in the transwell migration and invasion assays were determined in preliminary experiments. After incubation, non-migrating cells on the upper side of the membrane were removed with a cotton swab, and invading cells attached to the bottom membrane were fixed with methanol, stained with crystal violet, and lysed with 10% acetic acid, after which the optical density was measured using a plate reader (iMax, Bio-Rad) at 495 nm (OD495). The spontaneous migration/invasion of cells through the membrane without the chemotactic gradient was also measured and subtracted from each OD495 value. The basal migration/invasion of heparinase/chlorate-treated cells without stimulation with Hsp90 was calculated by comparing the OD495 values of control and treated cells and expressed in percent (the OD495 value of control cells was taken as 100%). To calculate the Hsp90-stimulated migration/invasion, the OD495 values of unstimulated cells were subtracted from the OD495 values of Hsp90-stimulated cells, and the residual was expressed in percent relative to the OD495 values of unstimulated control, heparinase-, and chlorate-treated cells. To compare the Hsp90-stimulated migration/invasion of control and heparinase/chlorate-treated cells, the Hsp90-induced stimulation of migration/invasion of control cells was taken as 100%. To analyze the effect of heparin, chondroitin sulfate A, or dermatan sulfate on the basal and Hsp90-stimulated cell migration/invasion, the transwell migration/invasion assays were performed as described above in the presence of sulfated glycosaminoglycans (50 μg/ml).

Flow cytometry

Cells were treated with a heparinase I/III blend and sodium chlorate as described above. The influence of different sulfated glycosaminoglycans on the attachment of Hsp90α and Hsp90β to the plasma membrane was analyzed by treating the cells for 1 h at 37 °C with heparin, chondroitin sulfate A, or dermatan sulfate diluted in DMEM-FBS to a concentration of 50 μg/ml. After the treatment, cells were detached from culture dishes by incubation for 5 min at 37 °C with 0.05% Na-EDTA and washed with cold PBS containing 0.05% NaN3 (PBS-NaN3). The cells were incubated with primary mouse antibodies, washed, and incubated with Alexa 488-labeled anti-mouse IgG conjugates. All incubations with antibodies and conjugates were performed for 1 h at 4 °C in PBS-NaN3 containing 2% BSA. Then, cells were washed, fixed with 0.5% formaldehyde for 15 min at 4 °C, and analyzed using an Accuri C6 flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). Autofluorescence and isotype controls were run routinely for all assays. Each analysis included at least 50,000 events of gated cells. The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) was determined using the BD Accuri C6 software. To quantify the flow cytometry data, MFI of respective isotype controls were subtracted from specific MFI and the levels of surface proteins were expressed as the respective MFI ± SD.

Western blot analysis

Cells were treated with heparinase and sodium chlorate and stimulated by native Hsp90 as indicated above. Then, cells were lysed in PBS containing 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% deoxycholate, 0.3% SDS, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 200 nM aprotinin, 50 μM leupeptin, 10 μM pepstatin A, and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail 3 (Sigma-Aldrich). Cell samples were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. The membrane was blocked in PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 and 2% BSA (PBS-T-BSA), and membrane strips were probed with AKT1/2/3-, pAKT1/2/3-, or β-actin-specific antibodies. The strips were washed and incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary anti-rabbit IgG or anti-mouse IgG antibodies in PBS-T-BSA for 1 h. After thorough washing, immunoreactive bands were detected using the 3,3′-diaminobenzidine substrate. For the quantification, a densitometric analysis of Western blots was performed, following which band densities were normalized to β-actin (loading control) and quantified. In preliminary experiments, the dynamic linear range of band intensities for quantitative estimations was determined. To analyze purified Hsp90s, Hsp90 preparations were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, and membrane strips were probed with Hsp90α- and Hsp90β-specific antibodies.

Statistical data analysis

The data represent the average of three and more independent experiments. The results are expressed as the mean ± SD. The statistical significance was determined by the Student’s t test, and p < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

Enzymatic degradation of HS moieties of cell surface HSPGs diminishes the Hsp90-stimulated migration and invasion of cells

We used native Hsp90s to stimulate the migration and invasion of human glioblastoma A-172 and fibrosarcoma HT1080 cells. Native Hsp90s were purified from mouse, swine, and bovine brains as described (Skarga et al. 2009). Mouse Hsp90α and Hsp90β have 99% similarities with the respective human, pig, and bovine Hsp90 isoforms. The purity of Hsp90 approached 95–98%, as estimated by SDS-PAGE (additional file: Fig. S1a); in this case, the native Hsp90 consisted of both isoforms (additional file: Fig. S1b). In preliminary experiments, we observed that native mouse, bovine, and swine Hsp90s stimulated cell motility to approximately the same degree. Namely, native Hsp90s stimulated the migration of cells by 35–65% and the invasion of cells by 100–180% (additional file: Fig. S2a). Throughout the study, we used the purified native mouse Hsp90 at a concentration of 50 μg/ml. Mouse Hsp90 was not toxic for cells and did not affect the growth characteristics of A-172 and HT1080 cells at concentrations up to 1.0 mg/ml (additional file: Fig. S2b), indicating that Hsp90 did not influence cell proliferation.

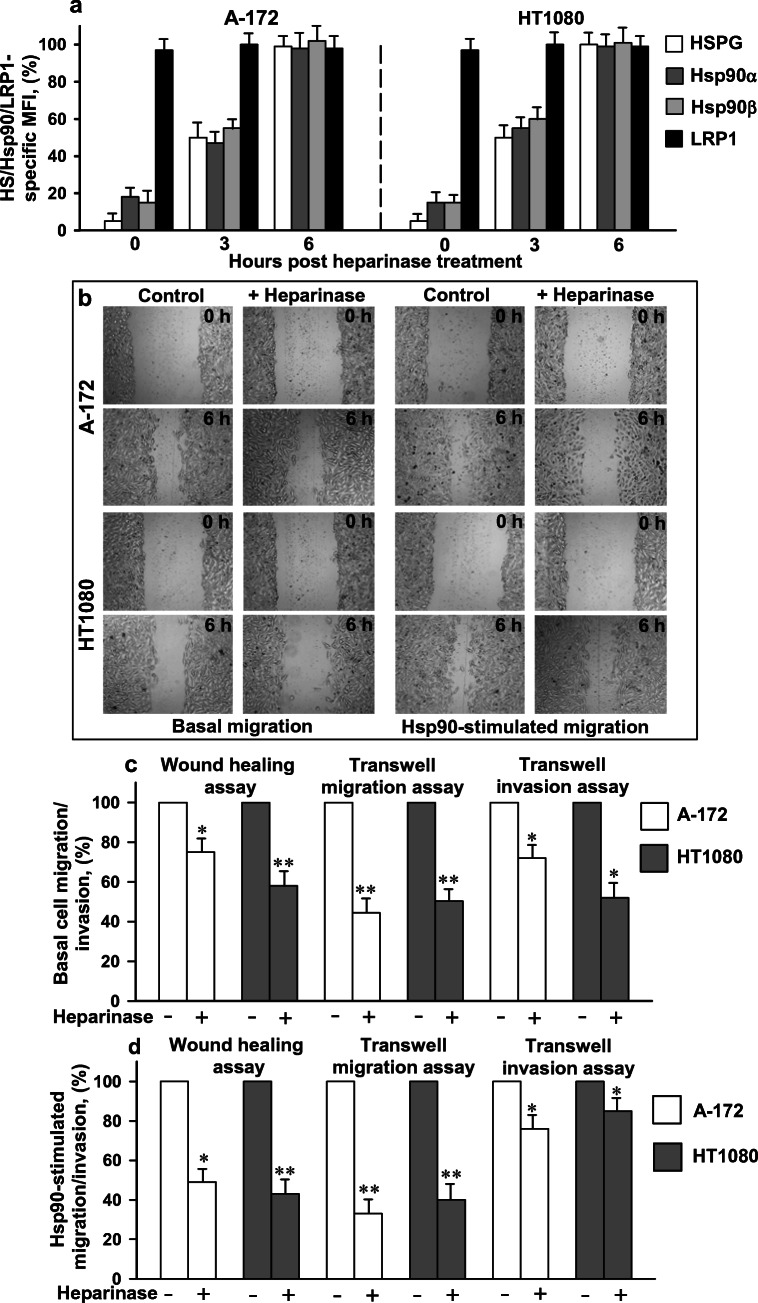

To elucidate the functional role of cell surface HSPGs in the Hsp90-stimulated migration/invasion of cells, HS moieties of HSPGs of HT1080 and A-172 cells were digested with heparinase followed by the analysis of the migration and invasion of cells in the presence of extracellular Hsp90. To ensure extensive degradation of the HS chains of HSPGs, a heparinase I/III blend was used since heparinase I and heparinase III specifically cleave, respectively, highly sulfated and less sulfated polysaccharide chains (Ernst et al. 1995). After the treatment, the reactivity of cells with the heparin/HS-specific antibody strongly diminished, which confirmed the profound degradation of HS moieties of surface HSPGs (Fig. 1a). The enzymatic degradation of cell surface HSPGs with heparinase was also accompanied by a considerable loss of Hsp90 isoforms from the cell surface (Fig. 1a), which was consistent with the results of our previous study (Snigireva et al. 2015). Further incubation of heparinase-treated cells in DMEM-FBS at 37 °C led to the coordinated restoration of the levels of Hsp90α, Hsp90β, and HSPGs at the cell surface; the almost complete restoration of cell surface expression of Hsp90s and HSPGs occurred within 6 h. The amount of cell surface LRP1 did not change during the treatment of cells with heparinase (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

Digestion of HS moieties of HSPGs with a heparinase reduces the level of HS and Hsp90s at the cell surface (a) and inhibits the basal and Hsp90-stimulated cell migration and invasion (b–d). a Cells were treated with a heparinase, after which cells were grown at 37 °C in DMEM-FBS. At indicated times, cell surface proteins were stained with specific antibodies, analyzed by flow cytometry, and quantified. The data are presented as the MFI specific for HS, Hsp90α, Hsp90β, and LRP1, expressed in percent. The specific MFI of control untreated cells was taken as 100%. b The migration of heparinase-treated cells in the wound-healing assay in the presence and absence of Hsp90. c The analysis of the basal migration/invasion of heparinase-treated cells. The migration/invasion of cells expressed in percent is presented. The basal migration/invasion of untreated control cells was taken as 100%. d The Hsp90-stimulated migration and invasion of heparinase-treated cells. The Hsp90-stimulated migration/invasion was calculated as described in the “Materials and methods” section and expressed in percent. The Hsp90-stimulated migration/invasion of control untreated cells was taken as 100%. a, c, d Each bar represents the mean ± SD (n = 3–4). *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 indicate statistically significant differences. The representative results from three independent experiments are shown

The enzymatic digestion of HSPGs also led to a 25–60% decrease in the basal (unstimulated) migration of cells in both migration assays and to a 25–50% reduction in the basal invasion of cells (Fig. 1b, c) as compared to control untreated cells. Moreover, extracellular Hsp90 less efficiently stimulated the migration/invasion in cells with heparinase-degraded HS moieties, as compared to control cells. Namely, after the digestion of HS moieties, the stimulation of cell migration by native Hsp90 in the wound-healing and transwell assays decreased by 50–65% as compared to the stimulation of control cells treated with Hsp90 in the same conditions (Fig. 1b, d). In the transwell invasion assay, the stimulation of invasion of heparinase-treated A-172 and HT1080 cells was reduced less significantly, by 10–30%, as compared to the stimulation of control cells (Fig. 1d). The results indicated that cell surface HSPGs are involved both in the basal and Hsp90-stimulated migration and invasion of cancer cells in vitro. Though the treatment of cells with heparinase drastically reduced the quantity of HS moieties on the surface, the cells were still able to respond to the treatment with extracellular Hsp90. Thus, extracellular Hsp90 is able to activate to some extent cell motility in an HSPG-independent manner, and surface HSPGs promote the Hsp90-induced stimulation of cell migration and invasion.

Undersulfation of HS moieties of HSPGs decreases the Hsp90-stimulated migration and invasion of cells

We further examined the effect of inhibition of sulfation of HS chains on the Hsp90-stimulated migration/invasion of cells. Sodium chlorate reduces the sulfation of HSPG polysaccharide chains during their biosynthesis (Safaiyan et al. 1999). We observed that the cultivation of cells in a medium containing sodium chlorate at a concentration of 30 mM for 24–48 h did not affect cell proliferation and viability (data not shown). The treatment of cells for 24 h with sodium chlorate led to a 5–20-fold diminishing in the reactivity of the HS-specific antibody with cells, indicating a dramatic decrease in the quantity of sulfated HS moieties on the cell surface (Fig. 2a). The undersulfation of HSPGs with sodium chlorate was also accompanied by a considerable decrease in the levels of Hsp90α and Hsp90β at the cell surface, whereas the level of cell surface LRP1 decreased only by 20–30% (Fig. 2a). Further incubation of chlorate-treated cells in DMEM-FBS without chlorate at 37 °C resulted in a restoration of the levels of HSPGs and both Hsp90 isoforms at the cell surface that lasted for more than 24 h (Fig. 2a). The dynamics of the restoration of Hsp90α and Hsp90β levels at the cell surface correlated with that of HSPGs.

Fig. 2.

Metabolic inhibition of sulfation of HS chains leads to a loss of sulfated groups of HS, Hsp90α, and Hsp90β from the cell surface (a) and to an inhibition of the basal and Hsp90-stimulated cell migration and invasion (b–d). a Cells were treated with sodium chlorate, after which cells were grown at 37 °C in DMEM-FBS without chlorate. At indicated times, cell surface HS and proteins were stained with specific antibodies, analyzed by flow cytometry, and quantified. The data are presented as the MFI specific for HS, Hsp90α, Hsp90β, and LRP1, expressed in percent. The specific MFI of control untreated cells was taken as 100%. b The migration of chlorate-treated cells in the wound-healing assay in the presence and absence of Hsp90. c The analysis of the basal migration/invasion of chlorate-treated cells. The basal migration/invasion of cells expressed in percent is presented. The basal migration/invasion of untreated control cells was taken as 100%. d The Hsp90-stimulated migration and invasion of chlorate-treated cells. The Hsp90-stimulated migration/invasion was calculated as described in the “Materials and methods” section and expressed in percent. The Hsp90-stimulated migration/invasion of control untreated cells was taken as 100%. a, c, d Each bar represents the mean ± SD (n = 3–4). *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 indicate statistically significant differences. The representative results from three independent experiments are shown

Chlorate-treated cells migrated slower by 65–85% and 40–45% in the wound-healing and transwell migration assays, respectively, as compared to untreated cells (Fig. 2b, c). The basal invasion of chlorate-treated cells was also reduced, approximately by 50% (Fig. 2c). In addition to reduced basal migration and invasion, cells with undersulfated HSPGs exhibited a decrease in the stimulation of migration/invasion by extracellular Hsp90. Namely, the Hsp90-induced stimulation of migration of chlorate-treated cells decreased by 50–80% in the wound-healing assay and transwell migration assay as compared to that of control cells stimulated by Hsp90 (Fig. 2b, d). The Hsp90-stimulated invasion of chlorate-treated cells relative to control cells decreased by 10–20% (Fig. 2d). Altogether, the results further support our conclusion that cell surface HSPGs are involved in the basal and Hsp90-stimulated migration and invasion of cancer cells. Similarly to the enzymatic degradation of HSPGs, the metabolic inhibition of the sulfation of HS chains did not completely abrogate the stimulation of cells with extracellular Hsp90, suggesting that cell surface HSPGs rather facilitate the Hsp90-induced stimulation of cell migration/invasion than are absolutely required for this.

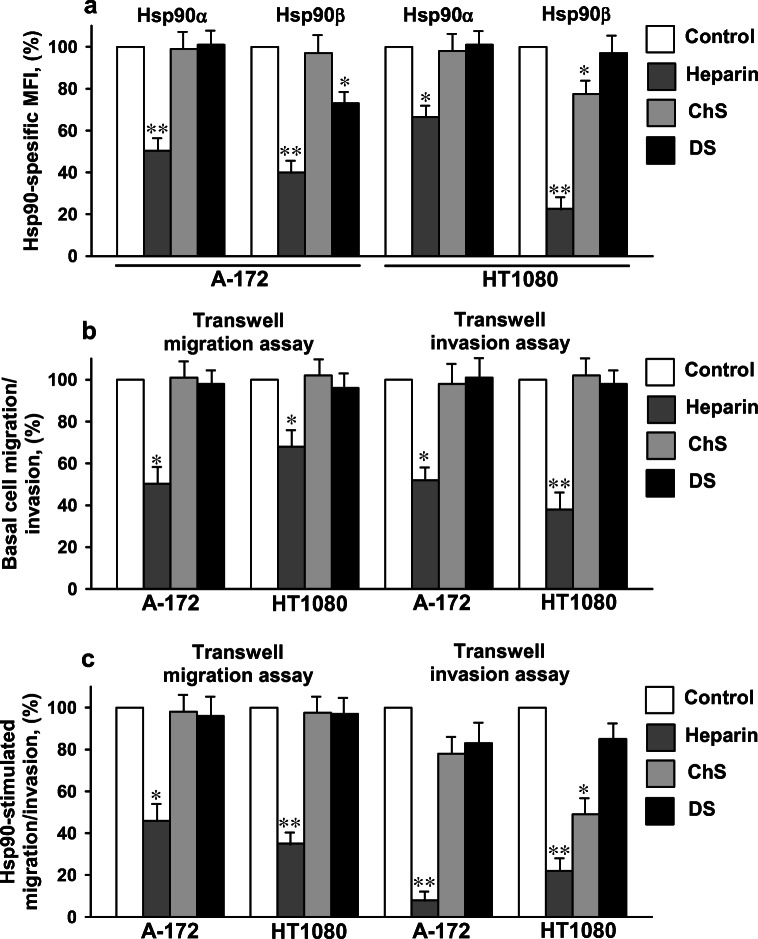

Heparin decreases the Hsp90-stimulated migration and invasion of cells

To further assess the involvement of cell surface HSPGs in the Hsp90-stimulated cell motility, we analyzed the effects of different sulfated glycosaminoglycans on the Hsp90-stimulated migration/invasion of A-172 and HT1080 cells. Heparin, a polysaccharide closely related to HS (Sarrazin et al. 2011), at a concentration of 50 μg/ml decreased the levels of Hsp90α and Hsp90β at the cell surface in both cancer cell lines by 30–55% and 60–80%, respectively (Fig. 3a). On the contrary, two other cell surface glycosaminoglycans, chondroitin sulfate A and dermatan sulfate, either did not dissociate or slightly dissociated Hsp90s from the cell surface (Fig. 3a). The results confirmed the specificity of the binding of Hsp90α and Hsp90β to the HS moieties of HSPGs, but not to cell surface proteoglycans containing chondroitin sulfate A and dermatan sulfate. The effect of heparin on the basal and Hsp90-stimulated migration and invasion was studied in the transwell migration and invasion assays. In the presence of heparin in the medium (50 μg/ml), the basal migration of A-172 and HT1080 cells was reduced by 30–50%, and the basal invasion of cells was suppressed by 40–80% (Fig. 3b). Heparin also decreased the degree of stimulation of cell migration by extracellular Hsp90: in the presence of heparin, the Hsp90-stimulated migration was reduced by 40–90% as compared to that without heparin (Fig. 3c). In the invasion assay, heparin also lowered the Hsp90-stimulated invasion of cells by 60–95% (Fig. 3c). In marked contrast, chondroitin sulfate A and dermatan sulfate did not change or only slightly decreased the Hsp90-stimulated cell migration. In the presence of chondroitin sulfate A and dermatan sulfate, the Hsp90-stimulated invasion of HT1080 cells diminished by 40–60% and 15–20%, respectively. In A-172 cells, chondroitin sulfate A and dermatan sulfate reduced the Hsp90-stimulated invasion by 15–30% (Fig. 3c). The results provided further evidence for the participation of cell surface HSPGs in the Hsp90-stimulated cell motility. The stimulation of cells with extracellular Hsp90 was not completely inhibited by heparin, suggesting the ability of extracellular Hsp90 to stimulate cell migration/invasion in the absence of its binding to HSPGs.

Fig. 3.

Treatment of A-172 and HT1080 cells with heparin results in a significant loss of Hsp90α and Hsp90β from the cell surface (a) and an inhibition of the basal and Hsp90-stimulated cell migration and invasion (b, c). a Cells were treated for 1 h at 37 °C with heparin, chondroitin sulfate A, or dermatan sulfate at a concentration of 50 μg/ml, stained with Hsp90α- and Hsp90β-specific antibodies, and analyzed by flow cytometry. The data are presented as the MFI specific for Hsp90α and Hsp90β, expressed in percent. The specific MFI of control cells was taken as 100%. b The analysis of the basal migration/invasion of cells in the transwell migration/invasion assays in the presence of heparin, chondroitin sulfate A, or dermatan sulfate at a concentration of 50 μg/ml. The basal migration/invasion of cells expressed in percent is presented. The basal migration/invasion of control cells without sulfated glycosaminoglycans was taken as 100%. c The Hsp90-stimulated migration/invasion of cells in the presence of heparin, chondroitin sulfate A, or dermatan sulfate at a concentration of 50 μg/ml was determined. The Hsp90-stimulated migration/invasion was calculated as described in the “Materials and methods” section and expressed in percent. The Hsp90-stimulated migration/invasion of control cells without sulfated glycosaminoglycans was taken as 100%. a–c Each bar represents the mean ± SD (n = 3–5). *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 indicate statistically significant differences. The representative results from three independent experiments are shown

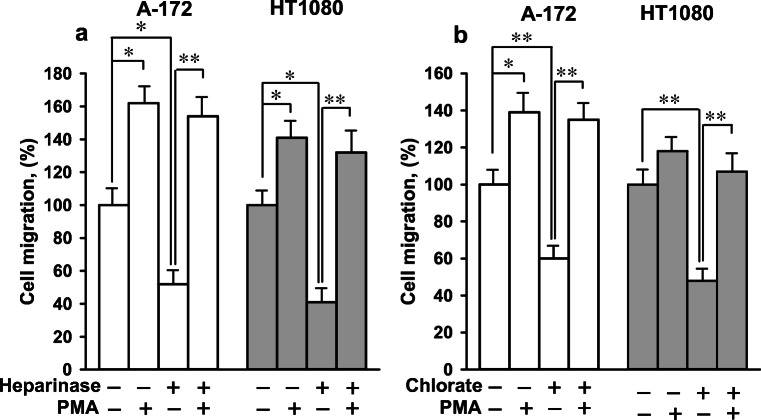

Heparinase- and chlorate-treated cells can migrate given an appropriate stimulus

To test whether the negative effects of heparinase and sodium chlorate were specific to Hsp90-stimulated motility or to cell motility in general, independently of the nature of the stimulus, we investigated the influence of phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) on the migration of cells with enzymatically degraded and undersulfated HS moieties of HSPGs. PMA is known as a potent intracellular agonist of protein kinase C capable to bypasses the ligand activation of receptors and directly activate cell motility (Nomura et al. 2007). Heparinase- and chlorate-treated cells migrated in the wound-healing assay 35–65% slower as compared to untreated cells (Fig. 4). PMA increased the rate of migration of control cells by 20–65%. In the presence of PMA, the rate of migration of heparinase- and chlorate-treated cells almost approached the rate of migration of PMA-induced control cells: the difference in the cell migration of PMA-induced control, heparinase-, and chlorate-treated cells was insignificant at a 95% confidence level (Fig. 4). Thus, given an appropriate intracellular stimulus, the migration of heparinase- and chlorate-treated cells was comparable to that of control cells, indicating that the degradation/undersulfation of HS chains of cell surface HSPGs did not considerably affect the cell motility machinery.

Fig. 4.

Enzymatic degradation (a) and undersulfation (b) of HS moieties of HSPGs did not considerably alter the cell motility machinery. The basal migration of heparinase- and chlorate-treated cells was analyzed in the wound-healing assay in the presence and absence of PMA (100 nM). The migration of cells expressed in percent is presented. The migration of control untreated cells without PMA was taken as 100%. Each bar represents the mean ± SD (n = 3–4). *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 indicate statistically significant differences. The representative results from three independent experiments are shown

Inhibition of the Hsp90-stimulated cell migration and invasion by the degradation/undersulfation of HS moieties of cell surface HSPGs occurs at the level of signal generation

Since the degradation and undersulfation of HS moieties did not affect the cell motility machinery, the decreased stimulation of migration and invasion of heparinase- and chlorate-treated cells by extracellular Hsp90 may be related to the impairment of transmission of Hsp90-generated signal from the cell surface into cells with digested/undersulfated HS chains. The stimulation of cells with extracellular Hsp90 leads to a receptor-mediated activation of different signaling pathways through phosphorylation of different kinases (Chen et al. 2010, 2013; Gopal et al. 2011; Thuringer et al. 2011). The activation of AKT-mediated pathway appears essential (though not sufficient) for the Hsp90-induced motility response (Chen et al. 2010, 2013; Gopal et al. 2011; Thuringer et al. 2011), and the level of phosphorylated AKT can be used to evaluate the efficiency of Hsp90 signaling in cells. Therefore, we monitored the phosphorylation status of AKT in heparinase- and chlorate-treated cells in response to extracellular Hsp90. The intensities of total AKT bands were virtually equal in different samples, indicating that the treatment of cells with heparinase and sodium chlorate and subsequent 2-h incubation of cells with Hsp90 did not change significantly the total AKT level in the cells. As expected, a 2-h treatment of A-172 and HT1080 cells with Hsp90 (50 μg/ml) raised the level of phosphorylated AKT in control untreated cells two to four times (Fig. 5), which is consistent with the results obtained by other researchers (Chen et al. 2010, 2013; Gopal et al. 2011; Thuringer et al. 2011). The stimulation of heparinase- and chlorate-treated cells with Hsp90 also led to an increase in the phosphorylation of AKT, but the increase was less pronounced: the level of phosphorylated AKT in heparinase- and chlorate-treated cells was reduced 1.3–2.8 and 2.0–2.5 times, respectively, as compared to control cells (Fig. 5). In chlorate-treated cells, the basal level of phosphorylated AKT was also slightly decreased.

Fig. 5.

Phosphorylation of AKT induced by extracellular Hsp90 is considerably suppressed in cells treated with heparinase (a, b) and sodium chlorate (c, d). Heparinase- and chlorate-treated cells were cultivated in a medium containing Hsp90 (50 μg/ml) for 2 h, and the cells were analyzed by Western blot to determine the levels of unphosphorylated/phosphorylated AKT. a, c Representative immunoblots of lysates of heparinase-treated (a) and chlorate-treated cells (c) are shown. b, d Quantification of band intensities of phosphorylated AKT. Band intensities were determined by densitometric analysis, normalized to β-actin intensities (loading control), and presented in arbitrary units. Each bar represents the mean ± SD (n = 3). *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 indicate statistically significant differences. The representative results from three independent experiments are shown

The degradation and undersulfation of HS did not completely abrogate but considerably inhibited the phosphorylation of AKT (Fig. 5), suggesting that cell surface HSPGs are not absolutely required for the extracellular Hsp90-induced signaling. The results provided direct evidence for the important role of cell surface HSPGs in potentiating the Hsp90-induced signaling.

Discussion

Earlier we have shown that cell surface HSPGs are involved in the binding of extracellular Hsp90 to cells (Snigireva et al. 2015). HSPGs can act at the cell surface as co-receptors for a range of structurally diverse effector proteins, and it seems likely that many of regulatory signals in the microenvironment of cells converge on HSPGs. HS chains interact with a wide range of growth factors, morphogenic proteins, and other soluble effectors (FGFs, HGF, VEGF, TGF-b1, TGF-b2, CC and CXC chemokines, and other soluble ligands), and play a role of “low-affinity” cell surface co-receptors that operate in dual-receptor systems to facilitate ligand binding to other higher-affinity receptors that transduce signals into the cell (Gallagher 2015; Lindahl and Li 2009; Sarrazin et al. 2011). Presumably, there are several distinct mechanisms by which cell surface HSPGs act as co-receptors. HSPGs may serve to sustain ligand gradients, deliver signaling proteins to signaling receptors, or directly participate in the formation of signaling complexes. HSPGs can also modulate ligand–receptor interactions by altering the stability or conformation of ligands. We hypothesized that the binding of HSPGs with extracellular Hsp90 may modulate its pro-motility activity. We used three approaches to investigate the role of cell surface HSPGs in the migration and invasion of human glioblastoma A-172 and fibrosarcoma HT1080 cells stimulated by extracellular Hsp90. The Hsp90-stimulated migration and invasion were investigated in cells treated with (1) a heparinase I/III blend, very specific enzymes for a mild elimination of HS from HSPGs (Ernst et al. 1995); (2) sodium chlorate, a specific metabolic inhibitor of glycosaminoglycan sulfation, that produces no observable effects on either protein synthesis or phosphorylation (Baeuerle and Huttner 1986; Safaiyan et al. 1999); and (3) heparin, a polysaccharide structurally similar to the HS moiety of HSPGs (Sarrazin et al. 2011). All three treatments led to a decrease in cell migration and invasion stimulated by native extracellular Hsp90, indicating an important role of surface-associated HSPGs in the Hsp90-stimulated migration and invasion of cells. The treatment of cells with heparinase, sodium chlorate, and heparin also affected the basal migration/invasion of cells. When analyzing the Hsp90-stimulated cell migration and invasion in treated cells, we considered the decrease in the basal migration/invasion of cells. Therefore, the Hsp90-stimulated migration/invasion of cells was calculated as a percent of stimulation of migration/invasion of control, heparinase-, chlorate-, and heparin-treated cells relative to the basal migration of, respectively, control, heparinase-, chlorate-, and heparin-treated cells.

We suppose that the weaker effects of degradation/undersulfation of HS moieties of HSPGs on the Hsp90-stimulated invasion than on the Hsp90-stimulated migration of cells can be explained by the different dynamics of the restoration of HS chains after different treatments. The HS level at the cell surface was almost fully restored within 6 h after the treatment of cells with heparinase and within more than 24 h after the treatment with sodium chlorate; the level of LRP1 decreased insignificantly during both treatments. Thus, in the course of the migration assay (6 h), the quantity of HS chains at the cell surface was reduced as compared to that in the invasion assay (24 h). We speculate that the more complete restoration of HS moieties of HSPGs in the invasion assay is advantageous for cell stimulation with extracellular Hsp90 and leads to an increase in the stimulation of heparinase/chlorate-treated cells in the transwell invasion assay.

The treatment of cells with heparinase had a more pronounced inhibitory effect on the basal invasion than on the Hsp90-stimulated invasion. Probably, the basal invasion is more dependent on the integrity of the surface HS than the Hsp90-stimulated invasion. Also, we should take into account that extracellular Hsp90 is able to stimulate cell migration/invasion in a HS-independent manner, which probably makes the Hsp90-mediated invasion less dependent on the surface HS.

The reduced stimulation of cell motility by extracellular Hsp90 in cells with digested/undersulfated HS chains can be explained either by the impairment of the motility machinery of the cell or by the inhibition of signal transduction from extracellular Hsp90 via cell receptors into the cell. We showed that the inhibition of Hsp90-driven stimulation of cell motility in heparinase- and chlorate-treated cells is brought about at the level of specific signal transduction through Hsp90 surface receptors. This was confirmed by the assay using PMA, an intracellular cell motility activator, that bypasses ligand activation of receptors (Nomura et al. 2007), and also by the analysis of downstream signaling in response to extracellular Hsp90. Indeed, heparinase- and chlorate-treated cells remained responsive to PMA and, after being treated with PMA, restored the basal migration almost to the control level, which suggested that the cell motility machinery was insignificantly affected in cells with degraded/undersulfated HS. The results were in concordance with other results demonstrating the retention of migration activity of cells after elimination of HS moieties and alteration in their sulfation (Chiodelli et al. 2011; Deakin and Lyon 1999). To evaluate the efficiency of Hsp90-induced cell signaling, we analyzed the level of phosphorylated AKT in cells with degraded/undersulfated HS chains since the AKT-mediated pathway, together with other signaling pathways, were reported to be activated in response to extracellular Hsp90 (Chen et al. 2010, 2013; Gopal et al. 2011; Thuringer et al. 2011). We observed that the phosphorylation of AKT in heparinase- and chlorate-treated cells in response to stimulation with extracellular Hsp90 was substantially reduced, indicating the impairment of signaling from extracellular Hsp90 into the cell.

Mechanistically, our findings support the idea that the optimal pro-motility activity of extracellular Hsp90 is dependent upon the presence of cell surface HSPGs that bind Hsp90. At the same time, extracellular native Hsp90 is able to induce signaling and activate cell motility in an HSPG-independent manner. Profound enzymatic degradation of HS moieties of HSPGs, severe undersulfation of HS, and the treatment of cells with heparin, which prevent the binding of native Hsp90 to HSPGs (Snigireva et al. 2015), were unable to completely abrogate the Hsp90-induced stimulation of migration and invasion of A-172 and HT1080 cells. The degradation and undersulfation of HS chains also reduced but did not completely prevent the phosphorylation of AKT induced by extracellular Hsp90 treatment. Thus, the pro-motility activity of extracellular Hsp90 is not critically dependent upon the presence of HSPGs at the cell surface. Rather, surface HSPGs facilitate the signal transmission from extracellular Hsp90 into the cell and, as a consequence, promote the Hsp90-stimulated migration and invasion of cells. The role of membrane-associated HSPGs in the Hsp90-stimulated motility seems to be similar to their role in promoting the action of some growth factors and morphogens (FGFs, HGF, VEGF, TGF-b1, TGF-b2, HB-EGF, Hedgehog, BMP, Wnt, etc.) where HSPGs are often required for the efficient ligand-induced signal transduction and cell activation (Dreyfuss et al. 2009; Higashiyama et al. 1993; Ornitz et al. 1992; Sarrazin et al. 2011).

The precise nature of the involvement of HS in the Hsp90-stimulated cell motility remains unclear. On the cell surface, HS chains may immobilize extracellular Hsp90 for further binding to signaling receptor(s) and signal transduction. The binding of extracellular Hsp90 to the HS chains of HSPGs reduces the dimensionality of interaction of Hsp90 with signaling receptor(s) from three (when Hsp90 is soluble) to two (when Hsp90 is bound to the HS chain), which can result in a local increase in Hsp90 concentration. Thus, the formation of Hsp90–HSPG complexes can increase the number of encounters between extracellular Hsp90 and the signaling receptor by bringing them together. Cell surface HSPGs may function in cell migration and invasion stimulated by extracellular Hsp90 in tandem with the known receptors of Hsp90, for example, with LRP1 (Basu et al. 2001; Chen et al. 2010; Cheng et al. 2008; Gopal et al. 2011). Cell surface HSPGs and LRP1 were earlier shown to function in a cooperative manner to mediate GRP94 cell surface binding (Jockheck-Clark et al. 2010), cellular uptake of C4b-binding protein (Spijkers et al. 2008), lipid metabolism (Wilsie and Orlando (2003), internalization of apoE/lipoprotein particles (Mahley and Ji 1999), and amyloid-beta uptake (Kanekiyo et al. 2011). Thus, HSPGs may facilitate LRP1-mediated Hsp90-induced cell motility. Several other mechanisms of action of cell surface HSPGs in the extracellular Hsp90-stimulated migration and invasion may also be suggested. Since active internalization of surface-associated Hsp90 was reported (Crowe et al. 2017), we cannot rule out that HSPG–Hsp90 complexes can be internalized, which may result in the modulation of motility-related signaling, including the potentiation of AKT phosphorylation. The binding of extracellular Hsp90 to cell surface HSPGs may simply stabilize the protein and prevent its degradation. Glypicans and syndecans, the members of two subfamilies of HSPGs, are located on the surface of most cells (Sarrazin et al. 2011; Gallagher 2015). The involvement of different glypicans and/or syndecans in the Hsp90-stimulated migration and invasion remains to be elucidated. Since syndecans were shown to signal via their protein cores (Lambaerts et al. 2009), direct signaling of extracellular Hsp90 through syndecans cannot be excluded.

In conclusion, our data provide new insights into the interplay between extracellular Hsp90 and cell surface HSPGs in the cell migration and invasion. Cell surface HSPGs facilitate the Hsp90-generated signaling in human cancer cells and thereby participate in the Hsp90-stimulated cell migration and invasion.

Electronic supplementary material

Purified native mouse Hsp90 was subjected to SDS-PAGE (a) and Western blot analysis with Hsp90α- and Hsp90β-specific antibodies (b). (PDF 95 kb)

The stimulation of migration and invasion of cells by native Hsp90s from different animal species (a) and the analysis of cytotoxicity and antiproliferative activity of native mouse Hsp90 (b). (a) The migration and invasion of cells were evaluated in the transwell migration/invasion assays in the absence and presence of mouse, swine, and bovine Hsp90 (50 μg/ml). The migration and invasion of cells were expressed in percent relative to that of control cells without Hsp90. Each bar represents the mean ± SD (n = 5). *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 indicate statistically significant differences. The representative results are shown. (b) For the determination of cytotoxicity, A-172 and HT1080 cells were grown in wells of 96-well plates till confluence, then mouse Hsp90 diluted at different concentrations in DMEM-FBS was added to cells, and the plates were incubated for 48 h at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. After incubation, 50 μl of an MTT solution (5 mg/ml) was added to each well, and the plates were incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. The medium was removed from the wells, precipitated crystals were dissolved with DMSO, and the optical density was measured at 495 nm (OD495). To determine the antiproliferative activity, the cells were placed in wells of 96-well plates (5.0–7.0 × 103 cells per well) in DMEM-FBS containing native mouse Hsp90 at different concentrations and incubated for 48 h. Staining with MTT and measurements of OD495 values were performed as described above. The absorbance of wells expressed in percent is presented, and OD495 values of control wells without Hsp90 is taken as 100%. Each figure represents the mean ± SD (n = 5). (PDF 43 kb)

Acknowledgments

We thank A.O. Shepelyakovskaya for the help with flow cytometry.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Baeuerle PA, Huttner WB. Chlorate—a potent inhibitor of protein sulfation in intact cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1986;141:870–877. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(86)80253-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu S, Binder RJ, Ramalingam T, Srivastava PK. CD91 is a common receptor for heat shock proteins gp96, hsp90, hsp70, and calreticulin. Immunity. 2001;14:303–313. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(01)00111-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker B, Multhoff G, Farkas B, Wild PJ, Landthaler M, Stolz W, Vogt T. Induction of Hsp90 protein expression in malignant melanomas and melanoma metastases. Exp Dermatol. 2004;13:27–32. doi: 10.1111/j.0906-6705.2004.00114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JS, Hsu YM, Chen CC, Chen LL, Lee CC, Huang TS. Secreted heat shock protein 90α induces colorectal cancer cell invasion through CD91/LRP-1 and NF-kB-mediated integrin αV expression. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:25458–25466. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.139345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WS, Chen CC, Chen LL, Lee CC, Huang TS. Secreted heat shock protein 90α (HSP90α) induces nuclear factor-κB-mediated TCF12 protein expression to down-regulate E-cadherin and to enhance colorectal cancer cell migration and invasion. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:9001–9010. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.437897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng CF, Fan J, Fedesco M, Guan S, Li Y, Bandyopadhyay B, Bright AM, Yerushalmi D, Liang M, Chen M, Han YP, Woodley DT, Li W. Transforming growth factor alpha (TGFalpha)-stimulated secretion of HSP90alpha: using the receptor LRP-1/CD91 to promote human skin cell migration against a TGFbeta-rich environment during wound healing. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:3344–3358. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01287-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng CF, Sahu D, Tsen F, Zhao Z, Fan J, Kim R, Wang X, O'Brien K, Li Y, Kuang Y, Chen M, Woodley DT, Li W. A fragment of secreted Hsp90α carries properties that enable it to accelerate effectively both acute and diabetic wound healing in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:4348–4361. doi: 10.1172/JCI46475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiodelli P, Mitola S, Ravelli C, Oreste P, Rusnati M, Presta M. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans mediate the angiogenic activity of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 agonist gremlin. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:e116–e127. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.235184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton A, Turkes A, Navabi H, Mason MD, Tabi Z. Induction of heat shock proteins in B-cell exosomes. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:3631–3638. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correia AL, Mori H, Chen EI, Schmitt FC, Bissell MJ. The hemopexin domain of MMP3 is responsible for mammary epithelial invasion and morphogenesis through extracellular interaction with HSP90β. Genes Dev. 2013;27:805–817. doi: 10.1101/gad.211383.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe LB, Hughes PF, Alcorta DA, Osada T, Smith AP, Totzke J, Loiselle DR, Lutz ID, Gargesha M, Roy D, Roques J, Darr D, Lyerly HK, Spector NL, Haystead TAJ. A fluorescent Hsp90 probe demonstrates the unique association between extracellular Hsp90 and malignancy in vivo. ACS Chem Biol. 2017;12:1047–1055. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.7b00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deakin JA, Lyon M. Differential regulation of hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor by cell surface proteoglycans and free glycosaminoglycan chains. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:1999–2009. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.12.1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreyfuss JL, Regatieri CV, Jarrouge TR, Cavalheiro RP, Sampaio LO, Nader HB. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans: structure, protein interactions and cell signaling. An Acad Bras Cienc. 2009;81:409–429. doi: 10.1590/S0001-37652009000300007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Hamidieh A, Grammatikakis N, Patsavoudi E. Cell surface Cdc37 participates in extracellular HSP90 mediated cancer cell invasion. PLoS One. 2012;7:e42722. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst S, Langer R, Cooney CL, Sasisekharan R. Enzymatic degradation of glycosaminoglycans. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1995;30:387–444. doi: 10.3109/10409239509083490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher J. Fell-Muir lecture: Heparan sulphate and the art of cell regulation: a polymer chain conducts the protein orchestra. Int J Exp Pathol. 2015;96:203–231. doi: 10.1111/iep.12135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopal U, Bohonowych JE, Lema-Tome C, Liu A, Garrett-Mayer E, Wang B, Isaacs JS. A novel extracellular Hsp90 mediated co-receptor function for LRP1 regulates EphA2 dependent glioblastoma cell invasion. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17649. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hance MW, Dole K, Gopal U, Bohonowych JE, Jezierska-Drutel A, Neumann CA, Liu H, Garraway IP, Isaacs JS. Secreted Hsp90 is a novel regulator of the epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) in prostate cancer. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:37732–37744. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.389015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higashiyama S, Abraham JA, Klgsbrun M. Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor stimulation of smooth muscle cell migration: dependence on interactions with cell surface heparan sulfate. J Cell Biol. 1993;122:933–940. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.4.933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter MC, O'Hagan KL, Kenyon A, Dhanani KC, Prinsloo E, Edkins AL. Hsp90 binds directly to fibronectin (FN) and inhibition reduces the extracellular fibronectin matrix in breast cancer cells. PLoS One. 2014;9:e86842. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jockheck-Clark AR, Bowers EV, Totonchy MB, Neubauer J, Pizzo SV, Nicchitta CV. Re-examination of CD91 function in GRP94 (glycoprotein 96) surface binding, uptake, and peptide cross-presentation. J Immunol. 2010;185:6819–6830. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanekiyo T, Zhang J, Liu Q, Liu CC, Zhang L, Bu G. Heparansulphate proteoglycan and the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 constitute major pathways for neuronal amyloid-beta uptake. J Neurosci. 2011;31:1644–1651. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5491-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagarrigue F, Dupuis-Coronas S, Ramel D, Delsol G, Tronchère H, Payrastre B, Gaits-Iacovoni F. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 is upregulated in nucleophosmin-anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive anaplastic lymphomas and activated at the cell surface by the chaperone heat shock protein 90 to promote cell invasion. Cancer Res. 2010;70:6978–6987. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambaerts K, Wilcox-Adelman SA, Zimmermann P. The signalling mechanisms of syndecan heparan sulphate proteoglycans. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21:662–669. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei H, Romeo G, Kazlauskas A. Heat shock protein 90alpha-dependent translocation of annexin II to the surface of endothelial cells modulates plasmin activity in the diabetic rat aorta. Circ Res. 2004;94:902–909. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000124979.46214.E3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Buchner J. Structure, function and regulation of the hsp90 machinery. Biom J. 2013;36:106–117. doi: 10.4103/2319-4170.113230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Li Y, Guan S, Fan J, Cheng CF, Bright AM, Chinn C, Chen M, Woodley DT. Extracellular heat shock protein-90alpha: linking hypoxia to skin cell motility and wound healing. EMBO J. 2007;26:1221–1233. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl U, Li JP. Interactions between heparin sulphate and proteins—design and functional implications. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2009;276:105–159. doi: 10.1016/S1937-6448(09)76003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisov A, Vrublevskaya V, Lisova Z, Leontievsky A, Morenkov O. A 2,5-Dihydroxybenzoic acid–gelatin conjugate: the synthesis, antiviral activity and mechanism of antiviral action against two alphaherpesviruses. Viruses. 2015;7:5343–5360. doi: 10.3390/v7102878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahley RW, Ji ZS. Remnant lipoprotein metabolism: key pathways involving cell-surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans and apolipoprotein E. J Lipid Res. 1999;40:1–16. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2275(20)33334-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCready J, Sims JD, Chan D, Jay DG. Secretion of extracellular hsp90α via exosomes increases cancer cell motility: a role for plasminogen activation. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:294. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsou I, Multhaupt HAB, Couchman JR. Proteoglycans, ion channels and cell-matrix adhesion. Biochem J. 2017;474:1965–1979. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20160747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura N, Nomura M, Takahira M, Sugiyama K. Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate-activated protein kinase C increased migratory activity of subconjunctival fibroblasts via stress-activated protein kinase pathways. Mol Vis. 2007;13:2320–2327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ornitz DM, Yayon A, Flanagan JG, Svahn CM, Levi E, Leder P. Heparin is required for cell-free binding of basic fibroblast growth factor to a soluble receptor and for mitogenesis in whole cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:240–247. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.1.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safaiyan F, Kolset SO, Prydz K, Gottfridsson E, Lindahl U, Salmivirta M. Selective effects of sodium chlorate treatment on the sulfation of heparan sulfate. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:36267–33673. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.51.36267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarrazin S, Lamanna WC, Esko JD. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3:a004952. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidera K, Samiotaki M, Yfanti E, Panayotou G, Patsavoudi E. Involvement of cell surface HSP90 in cell migration reveals a novel role in the developing nervous system. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:45379–45388. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405486200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidera K, Gaitanou M, Stellas D, Matsas R, Patsavoudi E. A critical role for HSP90 in cancer cell invasion involves interaction with the extracellular domain of HER-2. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:2031–2041. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701803200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skarga Y, Vrublevskaya V, Evdokimovskaya Y, Morenkov O. Purification of the 90 kDa heat shock protein (hsp90) and simultaneous purification of hsp70/hsc70, hsp90 and hsp96 from mammalian tissues and cells using thiophilic interaction chromatography. Biomed Chromatogr. 2009;23:1208–1216. doi: 10.1002/bmc.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snigireva AV, Vrublevskaya V, Afanasyev N, Morenkov O. Cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans are involved in the binding of Hsp90α and Hsp90β to the cell plasma membrane. Cell Adhes Migr. 2015;9:460–468. doi: 10.1080/19336918.2015.1103421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song X, Wang X, Zhuo W, Shi H, Feng D, Sun Y, Liang Y, Fu Y, Zhou D, Luo Y. The regulatory mechanism of extracellular Hsp90 on matrix metalloproteinase-2 processing and tumor angiogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:40039–40049. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.181941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spijkers PP, Denis CV, Blom AM, Lenting PJ. Cellular uptake of C4b-binding protein is mediated by heparan sulfate proteoglycans and CD91/LDL receptor-related protein. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:809–817. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sreedhar AS, Kalma’r E, Csermely P, Shen YF. Hsp90 isoforms: functions, expression and clinical importance. FEBS Lett. 2004;562:11–15. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00229-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki S, Kulkarni AB. Extracellular heat shock protein HSP90beta secreted by MG63 osteosarcoma cells inhibits activation of latent TGF-beta 1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;398:525–531. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.06.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thuringer D, Hammann A, Benikhlef N, Fourmaux E, Bouchot A, Wettstein G, Solary E, Garrido CJ. Transactivation of the epidermal growth factor receptor by heat shock protein 90 via toll-like receptor 4 contributes to the migration of glioblastoma cells. Biol Chem. 2011;286:3418–3428. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.154823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsumi S, Scroggins B, Koga F, Lee MJ, Trepel J, Felts S, Carreras C, Neckers L. A small molecule cell-impermeant Hsp90 antagonist inhibits tumor cell motility and invasion. Oncogene. 2008;27:2478–2487. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Song X, Zhuo W, Fu Y, Shi H, Liang Y, Tong M, Chang G, Luo Y. The regulatory mechanism of HSP90α secretion and its function in tumor malignancy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:21288–21293. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908151106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilsie LC, Orlando RA. The low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein complexes with cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans to regulate proteoglycan-mediated lipoprotein catabolism. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:15758–15764. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208786200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Purified native mouse Hsp90 was subjected to SDS-PAGE (a) and Western blot analysis with Hsp90α- and Hsp90β-specific antibodies (b). (PDF 95 kb)

The stimulation of migration and invasion of cells by native Hsp90s from different animal species (a) and the analysis of cytotoxicity and antiproliferative activity of native mouse Hsp90 (b). (a) The migration and invasion of cells were evaluated in the transwell migration/invasion assays in the absence and presence of mouse, swine, and bovine Hsp90 (50 μg/ml). The migration and invasion of cells were expressed in percent relative to that of control cells without Hsp90. Each bar represents the mean ± SD (n = 5). *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 indicate statistically significant differences. The representative results are shown. (b) For the determination of cytotoxicity, A-172 and HT1080 cells were grown in wells of 96-well plates till confluence, then mouse Hsp90 diluted at different concentrations in DMEM-FBS was added to cells, and the plates were incubated for 48 h at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. After incubation, 50 μl of an MTT solution (5 mg/ml) was added to each well, and the plates were incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. The medium was removed from the wells, precipitated crystals were dissolved with DMSO, and the optical density was measured at 495 nm (OD495). To determine the antiproliferative activity, the cells were placed in wells of 96-well plates (5.0–7.0 × 103 cells per well) in DMEM-FBS containing native mouse Hsp90 at different concentrations and incubated for 48 h. Staining with MTT and measurements of OD495 values were performed as described above. The absorbance of wells expressed in percent is presented, and OD495 values of control wells without Hsp90 is taken as 100%. Each figure represents the mean ± SD (n = 5). (PDF 43 kb)