Abstract

Ginkgolide terpenoid lactones, including ginkgolides and bilobalide, are two crucial bioactive constituents of extract of Ginkgo biloba (EGb) which was used in the treatment of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. The aims of this study were to investigate the antioxidant effects and mechanism of ginkgolides (ginkgolide A (GA), ginkgolide B (GB), ginkgolide K (GK)) and bilobalide (BB) against oxidative stress induced by transient focal cerebral ischemia. In vitro, SH-SY5Y cells were exposed to oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD) for 4 h followed by reoxygenation with ginkgolides and BB treatments for 6 h, and then cell viability, superoxide dismutase (SOD), and ROS were respectively detected using kit. Western blot was used to confirm the protein levels of hemeoxygenase-1 (HO-1), quinone oxidoreductase l (Nqo1), Akt, phosphorylated Akt (p-Akt), nuclear factor-E2-related factor2 (Nrf2), and phosphorylated Nrf2 (p-Nrf2). GB combined with different concentrations of LY294002 (PI3K inhibitor) were administrated to SH-SY5Y cells for 1 h after OGD, and then p-Akt and p-Nrf2 levels were detected by western blot. In vivo, 2 h of middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) model was established, followed with reperfusion and GB treatments for 24 and 72 h. The infarct volume ratios were confirmed by TTC staining. The protein levels of HO-1, Nqo1, SOD1, Akt, p-Akt, Nrf2, and p-Nrf2 were detected using western blot and immunohistochemistry (IHC). Experimental data in vitro confirm that GA, GB, GK, and BB resulted in significant decrease of ROS and increase of SOD activities and protein levels of HO-1 and Nqo1; however, GB group had a significant advantage in comparison with the GA and GK groups. Moreover, after ginkgolides and BB treatments, p-Akt and p-Nrf2 were significantly upregulated, which could be inhibited by LY294002 in a dose-dependent manner, meanwhile, GB exhibited more effective than GA and GK. In vivo, TTC staining indicated that the infarct volume ratios in MCAO rats were dramatically decreased by GB in a dose-dependent manner. Furthermore, GB significantly upregulated the protein levels of HO-1, Nqo1, SOD, p-Akt, p-Nrf2, and Nrf2. In conclusion, GA, GB, GK, and BB significantly inhibited oxidative stress damage caused by cerebral ischemia reperfusion. Compared with GA, GK, and BB, GB exerts the strongest antioxidant stress effects against ischemic stroke. Moreover, ginkgolides and BB upregulated the levels of antioxidant proteins through mediating the Akt/Nrf2 signaling pathway to protect neurons from oxidative stress injury.

Keywords: Ginkgo terpene lactones, Cerebral ischemia, Oxidative stress, Akt, Nrf2

Introduction

Stroke, including ischemic stroke caused by the block of cerebral blood vessel and hemorrhagic stroke with ruptured cerebral blood vessel, is a medical emergency that causes the devastating neurological function deficit (Zhou et al. 2018). With the treatment of acute stroke and world population health having improved substantially, the incidence and case fatality rates have declined over the past 10 years (Bushnell et al. 2018; Go et al. 2014), but stroke is still the major cause of death and adult disability worldwide (Zhou et al. 2018). Furthermore, in contrast with the declining incidence of stroke in older adults, epidemiologic studies consistently report an increasing incidence and proportion of young adult patients (18–50 years) with stroke within the total stroke population (one in ten strokes concerns a young adult) (Ekker et al. 2018). Because of the loss of labor productivity and high health-care costs, the additional incidence of stroke in young adults further increases the considerable socio-economic burden.

Ischemic stroke, responsible for about 87% of total strokes, causes neuronal cell death and injury of the neurovascular unit, which result in severe neurological symptoms (Zhou et al. 2018). The molecular mechanism of ischemic stroke is extremely complicated and remains not completely clear (Pradeep et al. 2012). Multiple pathophysiological processes are involved in cerebral ischemia, including energy metabolism disorder of nerve cell, excitotoxicity and acidosis, inflammation, apoptosis, and oxidative stress (Chamorro et al. 2016; Nakka et al. 2008; Robbins and Swanson 2014). In particular, oxidative stress can culminate in harmful effects during pathogenesis of ischemic stroke and reperfusion because of the excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and/or impaired ROS degradation (Rodrigo et al. 2013; Shirley et al. 2014; Zhang et al. 2017). Excessive ROS accumulation causes damage to cellular integrity and cellular dysfunction through lipid peroxidation and oxidation of protein, DNA, and RNA, thus leading to subsequent neurovascular cell autophagy, necrosis, or apoptosis within the affected brain tissue along with reversible or permanent neurological deficit (Allen and Bayraktutan 2009; Manzanero et al. 2013; Shirley et al. 2014).

Nuclear factor-E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) is one of the pivotal regulators of endogenous antioxidant defense molecules. Nrf2 promotes the transcription of various downstream antioxidant genes, including hemeoxygenase-1 (HO-1), quinone oxidoreductase-1 (Nqo1), and other phase II antioxidant enzyme (Alfieri et al. 2011; Jiang et al. 2017). Furthermore, recent studies have shown that Nrf2 plays an important role in protecting brain cells from ischemic stroke injury. Knockout of Nrf2 gene significantly increased cerebral infarction area and neurological deficits in ischemia reperfusion rats (Shah et al. 2007; Shih et al. 2005). Thus, Nrf2 is a promising therapeutic target for the treatment of stroke.

Extract of Ginkgo biloba (EGb) is one class of the most widely used natural products in the world. Ginkgolides and bilobalide, belonging to ginkgolide terpenoid lactones, are two crucial bioactive constituents of EGb (Zhou et al. 2016). Heretofore, ten kinds of diterpene lactone compounds including ginkgolide B (GB), ginkgolide A (GA), ginkgolide K (GK), and so on have been isolated from Ginkgo biloba leaves (Geng et al. 2018). Among them, GB was previously well known as the natural specific antagonists of platelet-activating factor (PAF) receptor (Wang et al. 2017). Now, GB has more extensive application in clinical therapy. Recent studies have confirmed that GB has a variety of pharmacologic effects on treating cancer (Sun et al. 2015; Zhi et al. 2016), diabetes (Wang et al. 2015), neurodegenerative diseases (Hua et al. 2017), especially cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. Furthermore, GB reduced nerve and blood vessel damage by inhibiting inflammation (Shu et al. 2016), degradation of membrane phospholipids (Pei et al. 2015), and so on. Meanwhile, as another active component of ginkgolide, GA could activate pregnane X receptor (PXR) and inhibit inflammation to protect liver and blood vessels (Li et al. 2017; Ye et al. 2016), but the effects on stroke or Nrf2 signaling pathway are not yet determined. In addition, GK is a derivative compound of GB for which research has become increasingly widespread. Recent studies have shown that GK decreased cerebral ischemia reperfusion injury by inhibiting mitochondrial dysfunction (Zhou et al. 2017), cell apoptosis (Liu et al. 2018), promoting angiogenesis (Chen et al. 2018), and protective autophagy (Zhang and Miao 2018). Besides, bilobalide (BB) is the only sesquiterpene lactone constituent of EGb, which has been widely used to treat various neurological disorders involving cerebral ischemia (Jiang et al. 2014), vascular dementia (Li et al. 2013b), and Alzheimer’s disease (Yin et al. 2013). Moreover, BB was confirmed to inhibit the production of pro-inflammatory mediator, improve mitochondrial function, and induce glutamate release to prevent cerebral ischemia-induced injury (Jiang et al. 2014; Lang et al. 2011).

In our present study, we established models of cerebral ischemia reperfusion in vivo and in vitro aimed to determine the anti-oxidative stress effects of ginkgolides and BB, and to compare the differences of their efficacy, further to explore the mechanism of regulating the antioxidant Akt/Nrf2 signaling pathway.

Methods

Materials

GA, GB, GK, and BB were extracted and separated by Jiangsu Kanion Modern Traditional Chinese Medicine Research Institute with 98% purity of high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (Lianyungang, Jiangsu Province, China). CCK-8 (the basis for this kit was WST-8) cell proliferation and cytotoxicity assay kit was obtained from BestBio (Shanghai, China); DMEM medium, glucose-free DMEM medium, and fetal bovine serum were purchased from Gibco (Waltham, MA, USA); anti-HO-1 antibody, anti-Nqo1 antibody, anti-Nrf2 antibody, anti-Nrf2 (phospho S40) antibody, anti-GAPDH antibody, anti-SOD1 antibody, and anti-beta actin antibody were obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, England); the HRP-conjugated secondary antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz (Dallas, TX, USA); anti-Akt (pan) antibody and anti-Akt (phospho T308) antibody were obtained from CST (Danvers, MA, USA); ROS assay kit, paraformaldehyde,2,3,5-triphenyl four azole nitrogen chloride (TTC), PI3K inhibitor LY294002, and SOD determination kit were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Darmstadt, Germany). Hypoxia chamber was obtained from Stemcell (Vancouver, Canada), Flex Station 3 Multi-Mode Microplate Reader was obtained from MD (San Francisco, CA, USA), and ChemiDoc XRS system was obtained from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA, USA).

Cell culture, oxygen-glucose deprivation model, and grouping

SH-SY5Y cells were purchased from Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (no. CRL-2266) which is imported from the ATCC (Shanghai, China). SH-SY5Y cells were seeded in 96-well plates with 2 × 104 cells/well and cultured overnight. For oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD), the culture medium of SH-SY5Y cells was replaced with glucose-free DMEM, and then SH-SY5Y cells were placed in a hypoxia chamber aerated with 95% N2 and 5% CO2 (O2 < 0.2%) at 37 °C in all experiments. In order to determine the optimal time of OGD, SH-SY5Y cells were cultured in DMEM without glucose under oxygen-free atmosphere for 0.5 h, 1 h, 2 h, 4 h, 6 h, and 8 h separately. Then, the cell viability was detected by CCK-8 kit with incubating WST-8 for 1 h and reading the absorbance at 450 nm using a microplate reader. Cell survival rate was calculated according to the formula: cell viability% = [(A − Ablank) / (Acontrol − Ablank)] × 100. The group of which the cell survival rate was about 50–60% after induction by OGD was selected as the model group. Similarly, after administration of different reoxygenation times and concentrations of drugs, the group of which the cell survival rate is at peak was selected as the experimental group for subsequent detection. Finally, SH-SY5Y cells were divided into six groups: control group, model group, and experimental groups (GA, GB, GK, and BB). The cells of experimental groups were induced by OGD for 4 h and then administrated with 25 mg/L GA, GB, GK, BB respectively under reoxygenation, and subsequently the ROS production, SOD activity, cell viability, and the protein levels were detected using kit and western blot respectively.

Measurement of oxidative stress

Oxidative stress was assessed by measuring ROS generation and SOD activity in SH-SY5Y cells induced by OGD for 4 h and then treatment with ginkgo terpenoid lactones and reoxygenation for 6 h. For detecting ROS, SH-SY5Y cells were incubated with 10-μM fluorescence probe DCFH-DA for 1 h at 37 °C, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After that, fluorescence intensity (λex = 488 nm, λem = 525 nm) was read using the fluorescence microplate reader. In the same way, as to SOD activity detection, cell samples were incubated with WST work solution and enzyme work solution in the kit at 37 °C for 20 min. Then, the absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader.

Rat MCAO model, GB treatment, and TTC staining

To explore the antioxidant effects of ginkgo terpenoid lactones in vivo, we established a MCAO model of cerebral ischemic injury with male SD rats purchased from Shanghai Sippr-BK laboratory animal company (Shanghai, China). All rats weighing 280–320 g were maintained at 22 ± 1 °C, 60–70% humidity with a 12 h light/dark cycle. All procedures used in this study were carried out according to the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the Ethics Committee for the Use of Experimental Animals of Jiangsu Kanion Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. State Key Laboratory of New Pharmaceutical Process for Traditional Chinese Medicine.

Surgical procedures were performed as described previously (Bai et al. 2016). In brief, rats were anesthetized with isoflurane and tied with supine position. Subsequently, the light common carotid artery (CCA), external carotid artery (ECA), and internal carotid artery (ICA) were exposed through a neck midline incision. The MCA was occluded by inserting an intraluminal silicone coating filament (Cinon Tech Co. Ltd., Beijing, China) into the CCA lumen and gently advanced into the ICA up to a point approximately 18 mm distal to the bifurcation of the carotid artery (Bai et al. 2016). And, correspondingly, arteries of sham rats were exposed but not ligated. Two hours after ischemia, MCAO rats were anesthetized again, and the filament was pulled out to restore blood flow for reperfusion. Two hours after reperfusion, different concentrations of GB (ip. 1 mg/kg, 2 mg/kg, and 4 mg/kg) were respectively administrated to rats twice a day. Then, 24 h after MCAO, the rats were sacrificed, and the brains were quickly removed and frozen. The protein expressions of HO-1, Nqo1, SOD1, p-Nrf2, Nrf2, p-Akt, and Akt in ischemic penumbra of the brain were determined by western blot. The protein expressions of p-Nrf2 and p-Akt were also detected by immunohistochemistry. For TTC staining, animals were killed at 72 h after MCAO, the brains were removed, and a series of 2-mm coronal slices were obtained and stained in 2% triphenyltetrazolium chloride dissolved with 0.9% saline; then, slices were photographed with a digital camera and the infarct volume was analyzed with Image-Pro Plus software.

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin coronal brain slices of ischemic penumbra with 5-μm thick were prepared at 24 h after MCAO. The slices were first blocked with normal goat serum for 1 h at room temperature. Then, slices were incubated with anti-Akt (phospho T308) antibody, anti-Nrf2 (phospho S40) antibody at 4 °C overnight. Subsequently, slices were incubated with goat anti-rabbit HRP-conjugated secondary antibody for 2 h at room temperature. Afterwards, the slices were incubated with DAB substrate to stain upon sealing by neutral balsam and cover glass. Finally, the stained slices were examined under DP73 Olympus imaging system (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Western blot and cell viability for antioxidant stress pathway analysis

The protein expressions of endogenous anti-oxidative stress pathway, including HO-1 and Nqo1, and the activation of Akt/Nrf2 pathway in OGD-induced SH-SY5Y cells were detected by western blot. SH-SY5Y cells were seeded in 5 × 106/dish of 100-mm2 size and cultured overnight. After OGD and compound treatment, SH-SY5Y cells were collected and washed with cold PBS, and then homogenized in ice-cold mammalian protein preparation buffer (Qiagen, Dusseldorf, Germany) containing phosphorylase inhibitors (Roche, Switzerland) for 30 min, followed by centrifugation at 14,000×g for 10 min at 4 °C. The protein concentrations were determined using BCA assay kit (Pplygen, Beijing, China). Fifty-microgram total protein per hole was separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gels, transferred onto a PVDF membrane, blocked with 5% nonfat milk, and then probed at 4 °C overnight with primary antibodies, including anti-HO-1, anti-Nqo1, anti-Nrf2, anti-Nrf2 (phospho S40), anti-Akt, anti-Akt (phospho T308), anti-SOD, anti-beta actin, and anti-GAPDH. Thereafter, the membranes were washed for three times and incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody at room temperature for 1 h. In the end, the protein bands were visualized with chemiluminescent reagents and quantified using an image analyzer Quantity One System (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA).

Rats were humanely killed after 24 h of MCAO with the third GB treatment. The ischemic penumbra regions of the brain were collected and then proteins were prepared by RIPA (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) containing protease and phosphorylase inhibitors (Roche, Switzerland). Eventually, western blot to analyze the protein activities was performed as above.

In addition to western blot, cell viability of SH-SY5Y cells was examined to confirm that the antioxidant stress pathway was in fact involved in the protection induced by OGD. LY294002 in different doses (12.5–50 μM) and GB were treated to SH-SY5Y cells for 6 h after OGD. Then, WST-8 (10 μL/well) was added to the cells and the absorbance was read at 450 nm using a microplate reader after incubation at 37 °C for 1 h.

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was repeated at least three times. Numerical data were presented as mean ± SD. The difference between means was analyzed with one-way ANOVA analysis using GraphPad Prism software version 5.0. P < 0.05 was considered to show a statistically significant difference.

Results

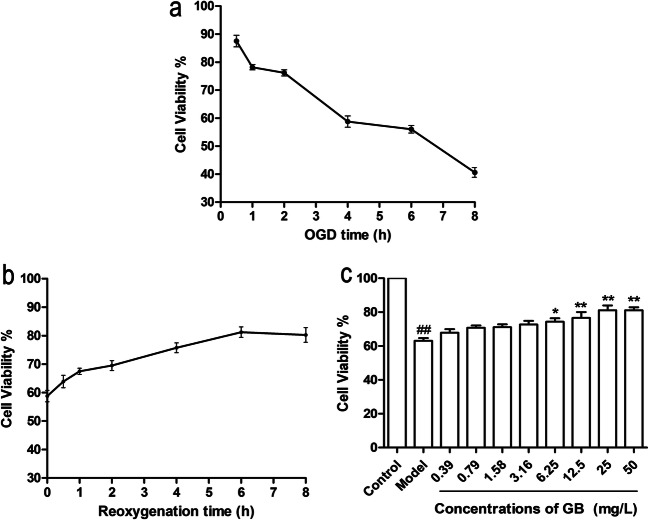

Optimization of OGD-reoxygenation time and concentration of constituents

We first examined cell viability to optimize OGD model conditions. As shown in Fig. 1a, cell vitality of SH-SY5Y cells decreased gradually with prolonged OGD time. When exposed to OGD for 4 h, the cell viability of SH-SY5Y cells was 58.77% ± 2.89. After induction by OGD for 4 h, SH-SY5Y cells were then treated with 25 mg/L GB and reoxygenation for different durations (0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8 h). The results in Fig. 1b indicated that GB treatment with reoxygenation for 6 h led to the highest cell vitality of SH-SY5Y cells. Taken together, SH-SY5Y cells exposed to OGD for 4 h and then treated with pharmaceutical compound and reoxygenation for 6 h were chosen as the optimum time of cerebral ischemia model in vitro. Next, we examined the effects of GB treatment at different concentrations (0.39–50 mg/L). The results in Fig. 1c demonstrated that GB significantly increased the cell viability in a dose-dependent manner, and GB treatment at the dose of 25 mg/L could result in the strongest protective effect on SH-SY5Y cells. Therefore, the dose of 25 mg/L of constituents was chosen as the optimum dosage for subsequent detection.

Fig. 1.

Detection of optimal OGD-reoxygenation time and concentration of compound treatments. a Cell viabilities of SH-SY5Y cells after OGD exposure for 0.5–8 h. b Cell viabilities of SH-SY5Y cells treated with reoxygenation and 25 mg/L GB treatment for 0.5–8 h after OGD. c Cell viabilities of SH-SY5Y cells treated with reoxygenation and different concentrations (0.39–50 mg/L) of GB treatment for 6 h after OGD. (Data are represented as mean ± SD from four experiments. ##P < 0.01 vs control group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs model group)

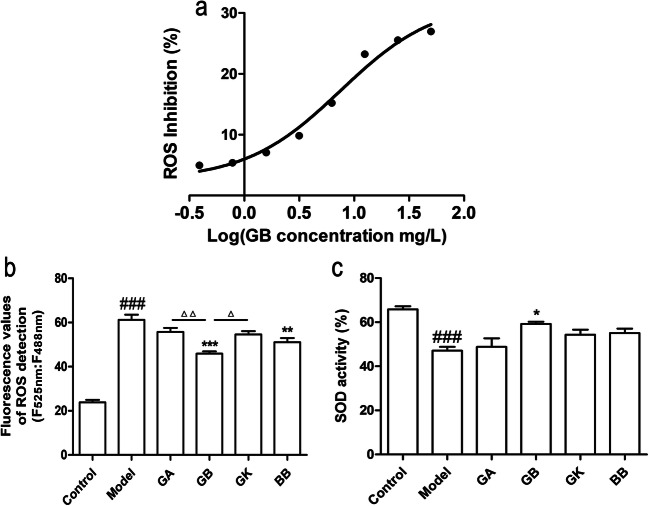

Ginkgolides and bilobalide decrease OGD-damaged SH-SY5Y cell oxidative stress injury

The antioxidant stress effects of ginkgolides and bilobalide on OGD-induced SH-SY5Y cells were assessed by measuring intracellular ROS generation and SOD activity. After exposure to OGD for 4 h, SH-SY5Y cells were treated with 0.39–50 mg/L GB and reoxygenation for 6 h. The data in Fig. 2a indicated that GB reduced the ROS production of oxidant stress in OGD-induced SH-SY5Y cells in a dose-dependent manner and the IC50 value was 7.523 mg/L. Furthermore, compared with the model group, the ROS production in GB and BB groups was found to be dramatically inhibited, and GB exhibited more effective than BB. In addition, the ROS inhibition in GB group had a significant advantage in comparison with the GA and GK groups (Fig. 2b). Therefore, GB was the most effective in inhibiting the ROS production. As for the detection of SOD activity in OGD-induced SH-SY5Y cells, the results in Fig. 2c demonstrated that exposure to OGD could markedly decrease the activity of SOD. However, GB treatment displayed an effective increase in SOD activity, and other components had no significant effects. In general, GB exhibited the strongest anti-oxidative stress effect compared with the other ginkgo terpenoid lactones.

Fig. 2.

Effects of ginkgolides and bilobalide on ROS levels and SOD activities in OGD-damaged SH-SY5Y cells. a ROS inhibition curve in OGD-damaged SH-SY5Y cells treated with different concentrations of GB for 6 h under reoxygenation. b ROS levels in OGD-damaged SH-SY5Y cells treated with 25 mg/L GA, GB, GK, and BB respectively for 6 h under reoxygenation. c SOD activities in OGD-damaged SH-SY5Y cells treated with 25 mg/L GA, GB, GK, and BB respectively for 6 h under reoxygenation. (Data are represented as mean ± SD from four experiments. ###P < 0.001 vs control group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 vs model group. △P < 0.05 was GB vs GK group, △△P < 0.01 was GB vs GA group)

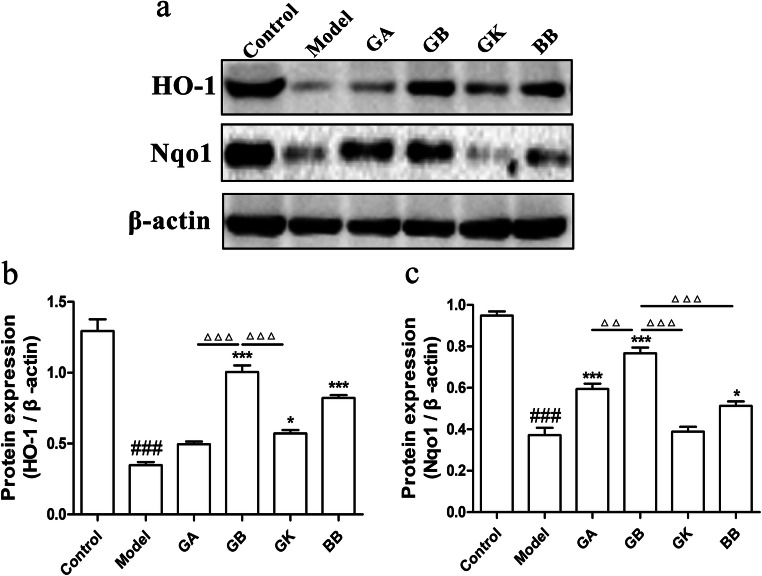

Ginkgolides and bilobalide increase the expressions of HO-1 and Nqo1 in OGD-induced SH-SY5Y cells

HO-1 and Nqo1 are two important endogenous molecules against oxidative stress injury. In order to determine the influence of ginkgolides and bilobalide on the protein levels of HO-1 and Nqo1, total proteins of SH-SY5Y cells exposure to OGD for 4 h followed by reoxygenation and constituents treatment for 6 h were prepared for western blot detection. Protein content analysis in Fig. 3 illustrated that HO-1 and Nqo1 levels were significantly decreased in the model group. While, GB, GK, and BB treatments could markedly elevate HO-1 expression compared with model group. Furthermore, HO-1 protein level in GB group was notably higher than that in GA and GK groups. In the meantime, GB, GA, and BB significantly upregulated Nqo1 expression in comparison with model group, and the effect of GB on increasing Nqo1 protein was dramatically better than that of other groups. Therefore, GB has the stronger regulatory activity of HO-1 and Nqo1 antioxidant molecules than the other ginkgo terpenoid lactones.

Fig. 3.

Effects of ginkgolides and bilobalide on expressions of HO-1 and Nqo1 in OGD-damaged SH-SY5Y cells. a Western blot detection of HO-1 and Nqo1 in SH-SY5Y cells with 25 mg/L GA, GB, GK, BB treatment for 6 h under reoxygenation. b Semi-quantitative results of HO-1 protein levels. c Semi-quantitative results of Nqo1 protein levels. (Data are represented as mean ± SD from three experiments. ###P < 0.001 vs control group. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 vs model group. △△△P < 0.001 was GB vs GA, GK, and BB groups)

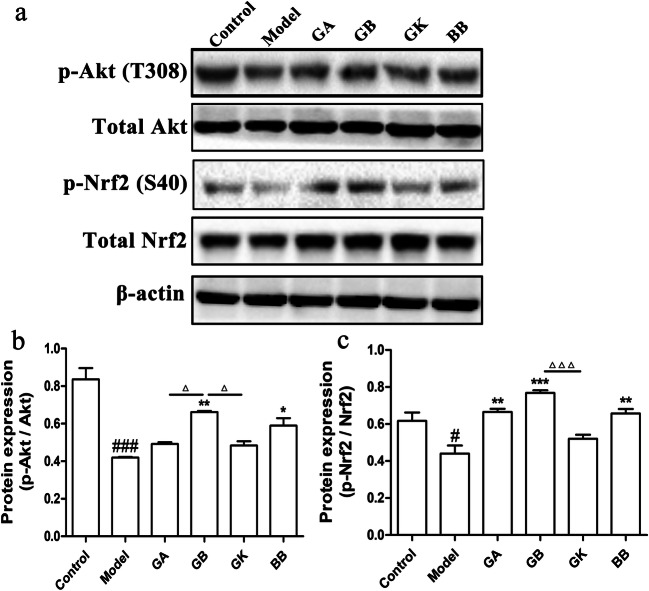

Ginkgolides and bilobalide activate Akt/Nrf2 signaling pathway in OGD-induced SH-SY5Y cells

Activation of Akt/Nrf2 signaling pathway can increase the expressions of HO-1 and Nqo1 to reduce oxidative stress damage in cells. Protein levels of p-Nrf2, Nrf2, p-Akt, and Akt in SH-SY5Y cells which were exposed to OGD for 4 h and then treated with constituents for 1 h under reoxygenation were consequently detected using western blot to investigate further the mechanism of antioxidant effects of ginkgo terpenoid lactones. As showed in Fig. 4, exposure to OGD resulted in significant downregulation of p-Akt/Akt and p-Nrf2/Nrf2, indicating the inhibition of the Akt/Nrf2 pathway. However, treating OGD-induced SH-SY5Y cells with GA, GB, and BB, except GK, for 1 h led to observable upregulation of p-Nrf2/Nrf2 and p-Akt/Akt levels. Moreover, in terms of p-Akt/Akt level, the GB group had a significant advantage over the GA and GK groups, and similarly, for the p-Nrf2/Nrf2 level, the GB group was significantly better than the GK group.

Fig. 4.

Effects of ginkgolides and bilobalide on expressions of p-Akt and p-Nrf2 in OGD-damaged SH-SY5Y cells. a Western blot detection of p-Akt, total Akt, p-Nrf2, and total Nrf2 in SH-SY5Y cells with 25 mg/L GA, GB, GK, BB treatment for 1 h under reoxygenation. b Semi-quantitative results of p-Akt/Akt protein levels. c Semi-quantitative results of p-Nrf2/Nrf2 protein levels. (Data are represented as mean ± SD from three experiments. ###P < 0.001 vs control group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs model group. △P < 0.01 was GB vs GA and GK groups, △△△P < 0.001 was GB vs GK group)

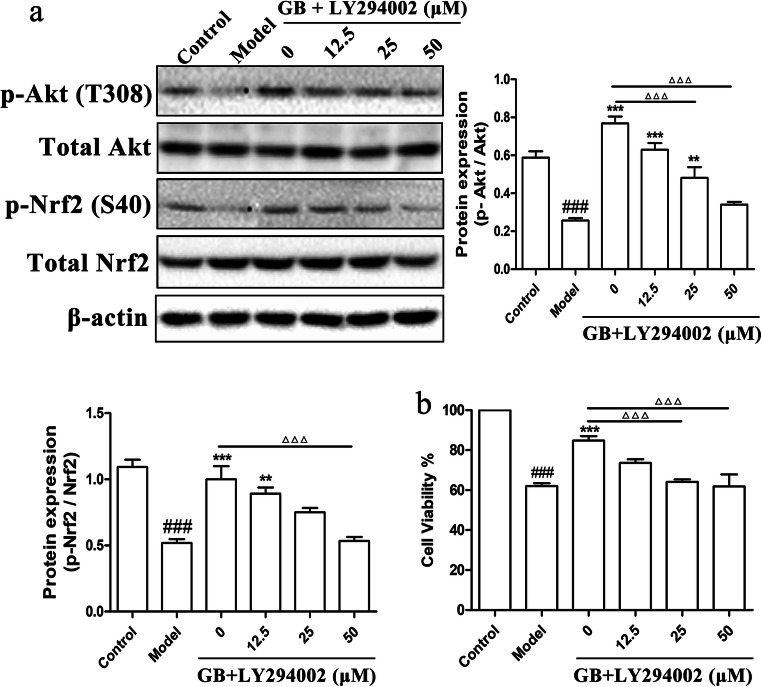

LY294002 reduces the activation of ginkgolides and bilobalide on the Akt/Nrf2 pathway and further inhibits its protective effect on SH-SY5Y cells damaged by OGD

In order to determine the relation between Akt and Nrf2, PI3K inhibitor (LY294002), which has been proved to inhibit the Akt activity, was administrated to SH-SY5Y cells combined with 25 mg/L GB for 1 h after OGD. Then, p-Nrf2/Nrf2 and p-Akt/Akt levels were detected by western blot. The results in Fig. 5a showed that the levels of p-Nrf2/Nrf2 and p-Akt/Akt were proportionately inhibited by LY294002 in a dose-dependent manner. 25–50 μM LY294002 considerably inhibited the phosphorylation of Akt, and also 50 μM LY294002 significantly decreased the activation of Nrf2. Therefore, the results suggested that Nrf2 activation might be mediated by PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Furthermore, to verify that Akt and Nrf2 are actually involved in the protection of ginkgolides and bilobalide, LY294002 in different doses and GB were treated to OGD-induced SH-SY5Y cells for 6 h. As shown in Fig. 5b, LY294002 at doses of 25–50 μM significantly reduced the cell viability of SH-SY5Y increased by GB, thereby mitigating the protective effect of GB. Thus, ginkgo terpenoid lactones might start up Akt/Nrf2 signaling pathway to protect neurons against cerebral ischemia injury.

Fig. 5.

Protein levels of Akt/Nrf2 pathway and cell viability of SH-SY5Y cells treated with LY294002 and GB. a Western blot analysis and semi-quantitative results of the protein levels of Nrf2, total Nrf2, p-Akt, and total Akt in SH-SY5Y cells with 25 mg/L GB and different concentrations (12.5–50 μM) of LY294002 treatments for 1 h. b Cell viabilities of SH-SY5Y cells treated with 25 mg/L GB and different concentrations (12.5–50 μM) of LY294002 for 6 h after OGD. (Data are represented as mean ± SD from three experiments. ###P < 0.001 vs control group. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs model group. △△△P < 0.001 was GB vs 25 μM LY294002 and 50 μM LY294002 groups)

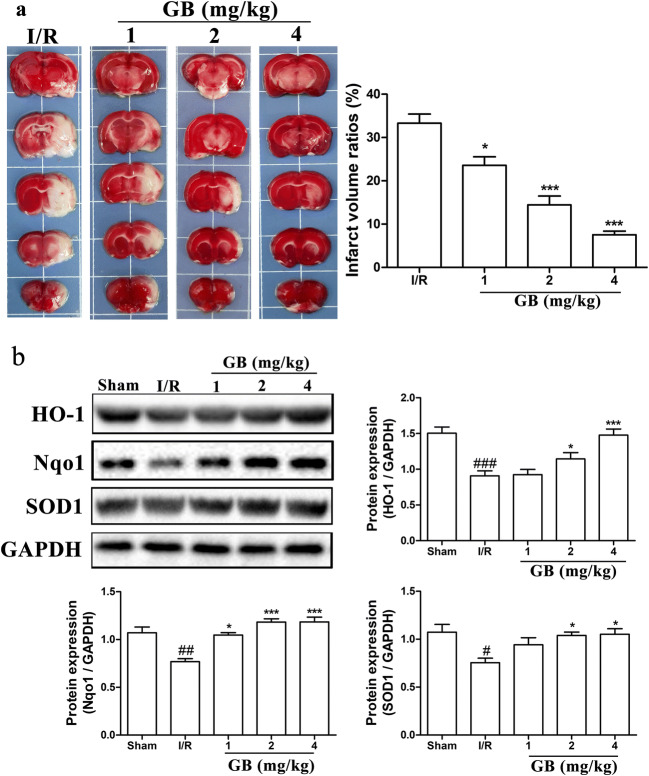

GB decreases infarct volume and increases the expressions of anti-oxidative stress–related proteins in MCAO rats

We further explored the anti-oxidative stress effect of GB, the major active ingredient of ginkgo terpenoid lactones, in rat MCAO model. Rats were under surgical procedures to produce ischemia for 2 h followed by reperfusion for 24/72 h. After 2 h of reperfusion, rats were treated with different concentrations of GB respectively. TTC staining was performed at 72 h of MCAO and the results in Fig. 6a indicated that the infarct volume ratios were significantly reduced by GB treatments in a dose-dependent manner. Moreover, protein levels of anti-oxidative stress–related proteins, SOD1, HO-1, and Nqo1, in ischemic penumbra of rat brain were detected using western blot at 24 h of MCAO. As showed in Fig. 6b, antioxidant related proteins in MCAO group decreased dramatically compared with normal group, and treating rats with different concentrations of GB resulted in clear increases in HO-1, Nqo1, and SOD1 expressions, similarly in a dose-dependent manner.

Fig. 6.

Effects of GB on infarct volume and expressions of antioxidant-related proteins in MCAO rats. a TTC staining and statistical analysis of the cerebral infarct area in MCAO rats treated with different concentrations of GB for 72 h. b Western blot analysis and semi-quantitative results of the protein levels of HO-1, Nqo1, and SOD1 in the ischemic penumbra area of MCAO rats treated with different concentrations of GB for 24 h. (Data are represented as mean ± SD from eight rats of each group. #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs sham group. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 vs I/R group)

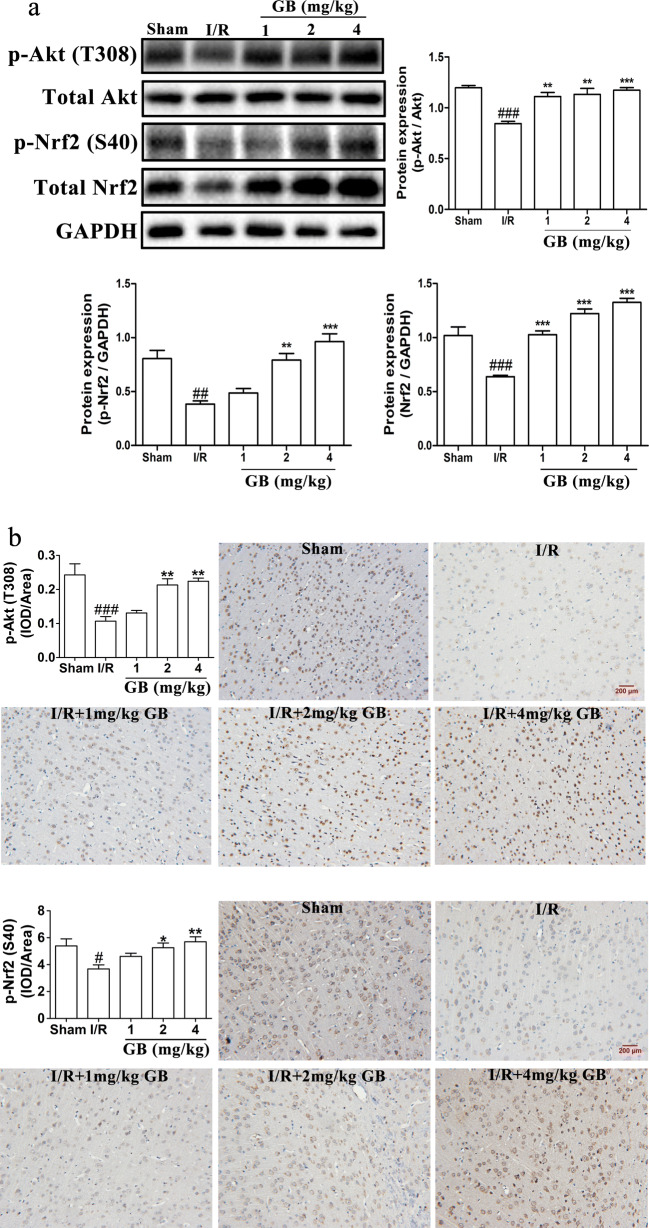

GB increases the expressions of p-Nrf2 and p-Akt in MCAO rats

To further determine the regulation effect of GB on Akt/Nrf2 signaling pathway, we detected p-Nrf2, Nrf2, p-Akt, and Akt protein levels in ischemic penumbra tissue of MCAO rats using western blot and IHC at 24 h of occlusion. The results in Fig. 7a showed that exposure to MCAO led to the protein levels of p-Nrf2, total Nrf2 and p-Akt/Akt obviously down-graduated in the ischemic penumbra area; however, after treated with different concentrations of GB, the protein levels of p-Nrf2, total Nrf2, and p-Akt/Akt markedly increased in a dose-dependent manner. Similarly, as showed in Fig. 7b, p-Nrf2 and p-Akt were effectively upregulated in 2 and 4 mg/kg GB groups in a dose-dependent manner.

Fig. 7.

Effects of GB on protein expressions of p-Akt and p-Nrf2 in MCAO rats. a Western blot analysis and semi-quantitative results of the protein levels of p-Akt, total Akt, p-Nrf2, and total Nrf2 in the ischemic penumbra area of MCAO rats treated with different concentrations of GB for 24 h. b Immunohistochemistry staining and statistical analysis of the protein levels of p-Akt and p-Nrf2 of MCAO rats treated with different concentrations of GB for 24 h. (Data are represented as mean ± SD from eight rats of each group. #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs sham group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs I/R group)

Discussion

Oxidative stress injury plays a critical role in the pathological development of cerebral ischemia reperfusion. Recent clinical study based on a population-based cohort of 9949 older adults from Germany with 14 years corroborated that urinary biomarkers of oxidative stress can predict myocardial infarction, stroke, and cardiovascular mortality, indicating the high involvement of an imbalanced redox system to the etiology of cerebral ischemia reperfusion (Xuan et al. 2018). In our present study, we established the OGD-induced SH-SY5Y cell model and MCAO rat model for cerebral ischemia reperfusion disease, and increase of ROS production and decrease of SOD activity were found, HO-1 and Nqo1 antioxidant molecules level both in vitro and in vivo, leading to a significant growth of oxidative stress damage in ischemic stroke. Moreover, our findings also confirmed that ginkgolides and BB treatment could protect against the oxidant stress through inhibiting ROS production, upregulating SOD activity, and protein expressions of HO-1 and Nqo1 in cell model and MCAO rat model. In particular, the efficacy of GB was better than BB and significantly better than GA and GK. Therefore, GB may be the most effective active ingredient of ginkgo terpenoid lactones for anti-oxidative stress injury in ischemic stroke. This result is consistent with previous literature report that BB showed less protective effects compared with GB during hyperglycemic cerebral ischemia (Huang et al. 2012). Although the structures of GA, GB, GK, and BB are similar, ginkgolides have the same parent nuclear structure, their pharmacological activities are different actually. Previous studies have confirmed that the lack of convulsant effects of GA and GB, and BB may be associated in part with their different binding locations within the chloride channel (GABAA receptor) (Ng et al. 2016; Ng et al. 2017). Furthermore, GA is the main active constituent against mice anxiety injuries in EGb761, compared with GB, ginkgolide C (GC) and BB (Kuribara et al. 2003). And, by comparison, only GA increased CYP3A23 gene expression and enzyme activities by G. biloba extract in primary cultures of rat hepatocytes. In the same way, only BB increased CYP2B1 mRNA expression in primary cultures of rat hepatocytes (Chang et al. 2006). In addition, GK, not GB, promoted the clearance of A53T mutation alpha-synuclein in SH-SY5Y cells, showing that GK is a potentially new therapeutic candidate for Parkinson’s disease (Yu et al. 2018). Therefore, each of the compounds in ginkgo diterpenoid lactone may have different pharmacological activities against ischemic stroke.

A number of studies have confirmed that the loss of Nrf2 aggravates cerebral infarction and neural function defects in MCAO rats (Li et al. 2013a; Shah et al. 2007; Shih et al. 2005). Therefore, Nrf2 signaling pathway plays the crucial role in the inhibition of ischemic stroke damage. Under normal physiological conditions, Nrf2 binds to the natural inhibitor Keap1 in the cytoplasm to maintain stability of activity (Alfieri et al. 2011). In response to cellular insults and/or phosphorylation by various protein kinases, Nrf2 is activated with releasing from Keap1. PI3K/Akt pathway is involved in the phosphorylation of Nrf2 at ser 40, and inhibition of PI3K or Akt attenuates Nrf2 activation (Li et al. 2006; Nakaso et al. 2003). After releasing from Keap1, p-Nrf2 is activated in the cytoplasm, transposes into the nucleus, heterodimerizes with bZIP proteins such as Maf proteins, and recognizes the appropriate ARE sequence (Chen et al. 2015; Niture et al. 2014; Zhang et al. 2017). As a result, it initiates the transcription of a series of anti-oxidative genes harboring ARE in the promoter region, including SODs, HO-1, Nqo1, and GSTs (Harvey et al. 2009; Jiang et al. 2017; Shelton et al. 2013). These antioxidant molecules protect cells against oxidative stress through various enzymatic catalytic reactions. SODs catalyze the dismutation of O2– to form O2 and H2O2, which is then converted to the final product of water (Zhang et al. 2015). HO-1 catalyzes the oxidation of heme to free iron, biliverdin, and carbon monoxide (Otterbein and Choi 2000). And, Nqo1 catalyzes two-electron reduction of quinones involved in generating ROS (Ross and Siegel 2004). In the present study, our result revealed that ginkgolides and BB activated Nrf2 by PI3K/Akt protein kinase phosphorylation, and then promoted the expression of HO-1, Nqo1, SOD, and other proteins to inhibit the oxidative stress injury of cerebral ischemia reperfusion. Furthermore, the phosphorylation of Nrf2 was concentration-dependently downregulated as the p-Akt was inhibited by PI3K inhibitor (LY294002), suggesting that the anti-oxidative effect of ginkgolides and BB was dependent on the activating of PI3K/Akt/Nrf2 signaling pathway. Similarly, it has been reported that Diterpene ginkgolides meglumine injection (DGMI), the main components of which are GA, GB, and GC, activated Nrf2 and CREB through PI3K/Akt signaling pathway to inhibit apoptotic damage of nerve cells in ischemic stroke (Zhang et al. 2018).

In conclusion, our findings demonstrated that ginkgolides and BB protect against oxidative stress in ischemic stroke. Compared with GA, GK, and BB, GB has the strongest antioxidant activity. The mechanism of antioxidant effects of ginkgolides and BB is possibly through activating PI3K/Akt pathway followed by Nrf2 phosphorylation and nuclear translocation, and increase in expressions of HO-1, Nqo1, and SOD.

Funding information

This study was supported by the grants from National Major Scientific and Technological Special Project for “Significant New Drugs Development” during the Twelfth Five-year Plan Period (2013ZX09402203).

Compliance with ethical standards

All procedures related to the use and care of animals in this study were approved by the Ethics Committee for the Use of Experimental Animals of Jiangsu Kanion Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. State Key Laboratory of New Pharmaceutical Process for Traditional Chinese Medicine.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Qiu Liu, Zhiquan Jin and Zhiliang Xu contributed equally to this work.

References

- Alfieri A, Srivastava S, Siow RC, Modo M, Fraser PA, Mann GE. Targeting the Nrf2-Keap1 antioxidant defence pathway for neurovascular protection in stroke. J Physiol. 2011;589:4125–4136. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.210294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen CL, Bayraktutan U. Oxidative stress and its role in the pathogenesis of ischaemic stroke. Int J Stroke. 2009;4:461–470. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2009.00387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai S, Hu Z, Yang Y, Yin Y, Li W, Wu L, Fang M. Anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects of triptolide via the NF-kappaB signaling pathway in a rat MCAO model. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2016;299:256–266. doi: 10.1002/ar.23293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushnell C, Howard VJ, Lisabeth L, Caso V, Gall S, Kleindorfer D, Chaturvedi S, Madsen TE, Demel SL, Lee SJ, Reeves M. Sex differences in the evaluation and treatment of acute ischaemic stroke. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17:641–650. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30201-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamorro A, Dirnagl U, Urra X, Planas AM. Neuroprotection in acute stroke: targeting excitotoxicity, oxidative and nitrosative stress, and inflammation. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15:869–881. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)00114-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang TK, Chen J, Teng XW. Distinct role of bilobalide and ginkgolide A in the modulation of rat CYP2B1 and CYP3A23 gene expression by Ginkgo biloba extract in cultured hepatocytes. Drug Metab Dispos. 2006;34:234–242. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.005751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B, Lu Y, Chen Y, Cheng J. The role of Nrf2 in oxidative stress-induced endothelial injuries. J Endocrinol. 2015;225:R83–R99. doi: 10.1530/JOE-14-0662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Zou W, Chen M, Cao L, Ding J, Xiao W, Hu G. Ginkgolide K promotes angiogenesis in a middle cerebral artery occlusion mouse model via activating JAK2/STAT3 pathway. Eur J Pharmacol. 2018;833:221–229. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2018.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekker M, Boot E, Singhal A, Tan K, Debette S, Tuladhar A, de Leeuw F. Epidemiology, aetiology, and management of ischaemic stroke in young adults. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17:790–801. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30233-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng T, Shen WW, Wang JJ, Huang WZ, Wang ZZ, Xiao W. Research development of ginkgo terpene lactones. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2018;43:1384–1391. doi: 10.19540/j.cnki.cjcmm.20180312.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Go A, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2014 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;129:e28–e292. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.003961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey CJ, Thimmulappa RK, Singh A, Blake DJ, Ling G, Wakabayashi N, Fujii J, Myers A, Biswal S. Nrf2-regulated glutathione recycling independent of biosynthesis is critical for cell survival during oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46:443–453. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.10.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua J, Yin N, Yang B, Zhang J, Ding J, Fan Y, Hu G. Ginkgolide B and bilobalide ameliorate neural cell apoptosis in alpha-synuclein aggregates. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;96:792–797. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang M, Qian Y, Guan T, Huang L, Tang X, Li Y. Different neuroprotective responses of Ginkgolide B and bilobalide, the two Ginkgo components, in ischemic rats with hyperglycemia. Eur J Pharmacol. 2012;677:71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang M, Li J, Peng Q, Liu Y, Liu W, Luo C, Peng J, Li J, Yung KKL, Mo Z. Neuroprotective effects of bilobalide on cerebral ischemia and reperfusion injury are associated with inhibition of pro-inflammatory mediator production and down-regulation of JNK1/2 and p38 MAPK activation. J Neuroinflammation. 2014;11:167. doi: 10.1186/s12974-014-0167-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang S, Deng C, Lv J, Fan C, Hu W, di S, Yan X, Ma Z, Liang Z, Yang Y. Nrf2 weaves an elaborate network of neuroprotection against stroke. Mol Neurobiol. 2017;54:1440–1455. doi: 10.1007/s12035-016-9707-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuribara H, Weintraub ST, Yoshihama T, Maruyama Y. An anxiolytic-like effect of Ginkgo biloba extract and its constituent, ginkgolide-A, in mice. J Nat Prod. 2003;66:1333–1337. doi: 10.1021/np030122f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang D, Kiewert C, Mdzinarishvili A, Schwarzkopf TM, Sumbria R, Hartmann J, Klein J. Neuroprotective effects of bilobalide are accompanied by a reduction of ischemia-induced glutamate release in vivo. Brain Res. 2011;1425:155–163. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li MH, Cha YN, Surh YJ. Peroxynitrite induces HO-1 expression via PI3K/Akt-dependent activation of NF-E2-related factor 2 in PC12 cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;41:1079–1091. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Zhang X, Cui L, Wang L, Liu H, Ji H, Du Y. Ursolic acid promotes the neuroprotection by activating Nrf2 pathway after cerebral ischemia in mice. Brain Res. 2013;1497:32–39. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li WZ, Wu WY, Huang H, Wu YY, Yin YY. Protective effect of bilobalide on learning and memory impairment in rats with vascular dementia. Mol Med Rep. 2013;8:935–941. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2013.1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, et al. Ginkgolide A ameliorates LPS-induced inflammatory responses in vitro and in vivo. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:794. doi: 10.3390/ijms18040794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Li X, Li L, Xu Z, Zhou J, Xiao W. Ginkgolide K protects SHSY5Y cells against oxygenglucose deprivationinduced injury by inhibiting the p38 and JNK signaling pathways. Mol Med Rep. 2018;18:3185–3192. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2018.9305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzanero S, Santro T, Arumugam TV. Neuronal oxidative stress in acute ischemic stroke: sources and contribution to cell injury. Neurochem Int. 2013;62:712–718. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2012.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakaso K, Yano H, Fukuhara Y, Takeshima T, Wada-Isoe K, Nakashima K. PI3K is a key molecule in the Nrf2-mediated regulation of antioxidative proteins by hemin in human neuroblastoma cells. FEBS Lett. 2003;546:181–184. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(03)00517-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakka VP, Gusain A, Mehta SL, Raghubir R. Molecular mechanisms of apoptosis in cerebral ischemia: multiple neuroprotective opportunities. Mol Neurobiol. 2008;37:7–38. doi: 10.1007/s12035-007-8013-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng CC, Duke RK, Hinton T, Johnston GA. GABAA receptor cysteinyl mutants and the ginkgo terpenoid lactones bilobalide and ginkgolides. Eur J Pharmacol. 2016;777:136–146. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2016.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng CC, Duke RK, Hinton T, Johnston GAR. Effects of bilobalide, ginkgolide B and picrotoxinin on GABAA receptor modulation by structurally diverse positive modulators. Eur J Pharmacol. 2017;806:83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2017.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niture SK, Khatri R, Jaiswal AK. Regulation of Nrf2-an update. Free Radic Biol Med. 2014;66:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otterbein LE, Choi AM. Heme oxygenase: colors of defense against cellular stress. Am J Phys Lung Cell Mol Phys. 2000;279:L1029–L1037. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.279.6.L1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei HX, Hua R, Guan CX, Fang X. Ginkgolide B reduces the degradation of membrane phospholipids to prevent ischemia/reperfusion myocardial injury in rats. Pharmacology. 2015;96:233–239. doi: 10.1159/000438945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradeep H, Diya J, Shashikumar S, Rajanikant G. Oxidative stress--assassin behind the ischemic stroke. Folia Neuropathol. 2012;50:219–230. doi: 10.5114/fn.2012.30522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins NM, Swanson RA. Opposing effects of glucose on stroke and reperfusion injury: acidosis, oxidative stress, and energy metabolism. Stroke. 2014;45:1881–1886. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.004889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigo R, Fernandez-Gajardo R, Gutierrez R, Matamala JM, Carrasco R, Miranda-Merchak A, Feuerhake W. Oxidative stress and pathophysiology of ischemic stroke: novel therapeutic opportunities. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2013;12:698–714. doi: 10.2174/1871527311312050015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross D, Siegel D. NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1, DT-diaphorase), functions and pharmacogenetics. Methods Enzymol. 2004;382:115–144. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)82008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah ZA, Li RC, Thimmulappa RK, Kensler TW, Yamamoto M, Biswal S, Dore S. Role of reactive oxygen species in modulation of Nrf2 following ischemic reperfusion injury. Neuroscience. 2007;147:53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.02.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton LM, Park BK, Copple IM. Role of Nrf2 in protection against acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2013;84:1090–1095. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih AY, Li P, Murphy TH. A small-molecule-inducible Nrf2-mediated antioxidant response provides effective prophylaxis against cerebral ischemia in vivo. J Neurosci. 2005;25:10321–10335. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4014-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirley R, Ord E, Work L. Oxidative stress and the use of antioxidants in stroke. Antioxidants (Basel) 2014;3:472–501. doi: 10.3390/antiox3030472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu ZM, Shu XD, Li HQ, Sun Y, Shan H, Sun XY, du RH, Lu M, Xiao M, Ding JH, Hu G. Ginkgolide B protects against ischemic stroke via modulating microglia polarization in mice. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2016;22:729–739. doi: 10.1111/cns.12577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, He Z, Ke J, Li S, Wu X, Lian L, He X, He X, Hu J, Zou Y, Wu X, Lan P. PAF receptor antagonist Ginkgolide B inhibits tumourigenesis and angiogenesis in colitis-associated cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:432–440. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GG, Chen QY, Li W, Lu XH, Zhao X. Ginkgolide B increases hydrogen sulfide and protects against endothelial dysfunction in diabetic rats. Croat Med J. 2015;56:4–13. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2015.56.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang KL, Li ZQ, Cao ZY, Ke ZP, Cao L, Wang ZZ, Xiao W. Effects of ginkgolide A, B and K on platelet aggregation. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2017;42:4722–4726. doi: 10.19540/j.cnki.cjcmm.2017.0207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xuan Y, Gao X, Holleczek B, Brenner H, Schottker B. Prediction of myocardial infarction, stroke and cardiovascular mortality with urinary biomarkers of oxidative stress: results from a large cohort study. Int J Cardiol. 2018;273:223–229. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye N, Wang H, Hong J, Zhang T, Lin C, Meng C. PXR mediated protection against liver inflammation by ginkgolide A in tetrachloromethane treated mice. Biomol Ther (Seoul) 2016;24:40–48. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2015.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y, Ren Y, Wu W, Wang Y, Cao M, Zhu Z, Wang M, Li W. Protective effects of bilobalide on Abeta(25-35) induced learning and memory impairments in male rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2013;106:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu W, Chen S, Cao L, Tang J, Xiao W, Xiao B. Ginkgolide K promotes the clearance of A53T mutation alpha-synuclein in SH-SY5Y cells. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2018;34:291–303. doi: 10.1007/s10565-017-9419-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Miao JM. Ginkgolide K promotes astrocyte proliferation and migration after oxygen-glucose deprivation via inducing protective autophagy through the AMPK/mTOR/ULK1 signaling pathway. Eur J Pharmacol. 2018;832:96–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2018.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Davies KJA, Forman HJ. Oxidative stress response and Nrf2 signaling in aging. Free Radic Biol Med. 2015;88:314–336. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.05.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R, Xu M, Wang Y, Xie F, Zhang G, Qin X. Nrf2-a promising therapeutic target for defensing against oxidative stress in stroke. Mol Neurobiol. 2017;54:6006–6017. doi: 10.1007/s12035-016-0111-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, et al. Diterpene ginkgolides protect against cerebral ischemia/reperfusion damage in rats by activating Nrf2 and CREB through PI3K/Akt signaling. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2018;39:1259–1272. doi: 10.1038/aps.2017.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhi Y, Pan J, Shen W, He P, Zheng J, Zhou X, Lu G, Chen Z, Zhou Z. Ginkgolide B inhibits human bladder cancer cell migration and invasion through microRNA-223-3p. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2016;39:1787–1794. doi: 10.1159/000447878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou JM, Gu SS, Mei WH, Zhou J, Wang ZZ, Xiao W. Ginkgolides and bilobalide protect BV2 microglia cells against OGD/reoxygenation injury by inhibiting TLR2/4 signaling pathways. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2016;21:1037–1053. doi: 10.1007/s12192-016-0728-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Wang HY, Wu B, Cheng CY, Xiao W, Wang ZZ, Yang YY, Li P, Yang H. Ginkgolide K attenuates neuronal injury after ischemic stroke by inhibiting mitochondrial fission and GSK-3beta-dependent increases in mitochondrial membrane permeability. Oncotarget. 2017;8:44682–44693. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, et al. Advances in stroke pharmacology. Pharmacol Ther. 2018;91:23–42. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2018.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]