Abstract

Introduction

This study aimed to assess how interindividual differences in locus coeruleus (LC) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contrast relate to cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers of Alzheimer's disease (AD).

Methods

LC MRI contrast was quantified in 73 individuals from the DZNE Longitudinal Cognitive Impairment and Dementia Study (DELCODE) study comprising 25 healthy elderly adults and 21 individuals with subjective cognitive decline, 16 with mild cognitive impairment, and 11 participants with AD dementia using 3D T1-weighted fast low-angle shot (FLASH) imaging (0.75 mm isotropic resolution). Bootstrapped Pearson's correlations between LC contrast, CSF amyloid, and tau were performed in 44 individuals with CSF biomarker status.

Results

A significant regional decrease in LC MRI contrast was observed in patients with AD dementia but not mild cognitive impairment and subjective cognitive decline compared with healthy controls. A negative association between LC MRI contrast and levels of CSF amyloid but not with CSF tau was found.

Discussion

These results provide first evidence for a direct association between LC MRI contrast using in vivo T1-weighted FLASH imaging and AD pathology.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease (AD), Locus coeruleus (LC), Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), Amyloid, Tau, Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Highlights

-

•

LC MRI contrast is reduced in Alzheimer's disease dementia (ADD) compared with healthy older adults.

-

•

Reduced MRI contrast in rostral/middle third of the LC in ADD is consistent with AD neuropathology.

-

•

LC MRI contrast negatively correlates with levels of cerebrospinal fluid amyloid.

1. Introduction

The locus coeruleus (LC) is the first region to develop neurofibrillary tangles [1] and may serve a critical role in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease (AD). It has been previously shown that the LC can be reliably located in vivo using neuromelanin-sensitive magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) approaches [2], [3], [4], [5], [6] and that interindividual differences in LC MRI contrast can predict memory performance in cognitively healthy older adults [7]. In this study, we investigated how LC MRI contrast relates to the pathophysiology of AD, i.e., as determined using cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers. Using first data from the DZNE Longitudinal Cognitive Impairment and Dementia (DELCODE) study [8], we assessed how LC contrast changes in individuals with subjective cognitive decline (SCD), mild cognitive impairment (MCI), Alzheimer's disease dementia (ADD), and age-matched healthy controls (HCs) related to levels of CSF amyloid and tau. We hypothesized a decrease in LC MRI contrast in ADD due to loss of neuromelanin-containing noradrenergic neurons would correlate with increased AD pathology.

2. Methods

2.1. Study participants

A total of 73 older adults comprising 25 HCs and 21 SCD, 16 MCI, and 11 ADD patients were recruited via the DELCODE study of the DZNE in Germany. SCD, MCI, and ADD were defined as previously described [8]. All patient groups (SCD, MCI, and ADD) were referrals, including self-referrals, whereas HCs were recruited by standardized public advertisement. For more information on subject inclusion criteria, refer to the study by Jessen et al. [8]. All participants gave written informed consent before inclusion in the study. For neuropsychological assessments and inclusion and exclusion criteria, refer to the study by Jessen et al. [8]. All local institutional review boards and ethical committees approved the study protocol.

2.2. CSF AD biomarker assessment

CSF AD biomarkers were determined using commercially available kits according to vendor specifications: V-PLEX Aβ Peptide Panel 1 (6E10) Kit (K15200E) and V-PLEX Human Total Tau Kit (K151LAE) (Meso Scale Diagnostics LLC, Rockville, MD, USA) and Innotest Phospho-Tau(181P) (81581; Fujirebio Germany GmbH, Hannover, Germany) as described previously [8].

2.3. MRI acquisition and determination of LC contrast

MRI data were acquired at two scanning sites, both using a Siemens Verio scanner. Whole-brain T1-weighted fast low-angle shot (FLASH) images were acquired using the following parameters: 0.75 × 0.75 × 0.75 mm3 voxel size, 320 × 320 × 192 matrix, 5.56 ms echo time, 20 ms repetition time, 23° flip angle, 130 Hz/pixel bandwidth, 7/8 partial Fourier, and 13:50 min scan duration as previously reported [5]. For a full description of the MRI protocol, refer to the study by Jessen et al. [8]. Images were sinc interpolated to 0.375 mm3 resolution before manual segmentation of the LC. Median LC signal and contrast ratios were determined relative to reference regions delineated in the rostral pontomesencephalic area as described previously [5]. LC signal contrast changes were also assessed in the rostral, middle, and caudal portions of the LC by splitting each individual's LC mask into three equally sized segments using FSL Maths in FSL, version 5.0 (http://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk).

3. Results

3.1. Demographic, cognitive, and clinical data

The results presented are from 73 individuals classified as HCs (n = 25; 9 males; 68 years) and SCD (n = 21; 13 males; 70 years), MCI (n = 16; 12 males; 71 years), or ADD patients (n = 11; 3 males; 71 years). In these individuals, Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale (ADAS) delayed recall scores were lower in patients with MCI and ADD (F3,69 = 39.3, both P < .001) and Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) scores were lower in patients with ADD (F3,69 = 60.0, P < .0001) but not in MCI or SCD compared with HCs (one-way Analaysis of Variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni post hoc tests). A significant difference in sex (F3,69 = 4.3, P = .01) but not in age and education was observed between groups. In 44 of these individuals with CSF biomarker status, CSF total tau (TTau) and phospho tau (PTau) values were significantly higher in patients with ADD than HCs (F3,40 = 10.0, P < .0001; F3,40 = 7.7, P < .001, respectively), whereas CSF Aβ42 levels were significantly decreased in patients with MCI and ADD (F3,40 = 11.4, both P ≤ .01) compared with HCs. In patients with MCI and ADD, a significant decrease in Aβ42/PTau181 (F3,40 = 12.6, both P ≤ .02), Aβ42/TTau (F3,40 = 12.7, both P ≤ .003), and the Hulstaert ratio [9] (F3,40 = 14.3, P ≤ .003) was observed compared with HCs (all values reported in Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants with locus coeruleus imaging and cerebrospinal fluid biomarker status

| HCs | SCD | MCI | ADD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 25 | 21 | 16 | 11 |

| Age (years) | 68.0 (4.7) | 70.0 (5.9) | 71.3 (5.5) | 71.4 (6.5) |

| Sex (M:F) | 9:16 | 13:8 | 12:4 | 3:8 |

| Education (years) | 15.2 (2.6) | 15.7 (2.8) | 14.4 (2.9) | 12.8 (2.6) |

| MMSE | 29.4 (0.9) | 29.0 (1.1) | 28.2 (1.2) | 22.7 (2.8)∗ |

| ADAS delayed recall | 8.3 (1.9) | 7.2 (2.0) | 4.2 (2.3)∗ | 1.4 (1.6)∗ |

| N | 17 | 10 | 10 | 7 |

| CSF TTau (pg/mL) | 329.9 (139.9) | 269.0 (95.0) | 598.7 (314.9) | 883.7 (502.2)∗ |

| CSF PTau181 (pg/mL) | 46.0 (17.5) | 36.5 (12.2) | 64.0 (27.3) | 106.6 (69.2)† |

| CSF Aβ42/Aβ40 | 0.1 (0.02) | 0.1 (0.01) | 0.07 (0.03)‡ | 0.05 (0.02)∗ |

| CSF Aβ42/PTau181 | 20.0 (4.2) | 20.2 (3.8) | 12.5 (9.1)‡ | 5.8 (6.0)∗ |

| CSF Aβ42/TTau | 2.9 (0.9) | 2.8 (1.0) | 1.5 (1.2)† | 0.6 (0.6)∗ |

| Hulstaert ratio | 1.4 (0.4) | 1.3 (0.4) | 0.8 (0.5)† | 0.4 (0.3)∗ |

Abbreviations: M, male; F, female; HC, healthy controls; SCD, subjective cognitive complaints; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; ADD, Alzheimer's disease dementia; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

P < .001 indicates significant differences compared with HCs (one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc tests).

P < .01 indicates significant differences compared with HCs (one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc tests).

P < .05 indicates significant differences compared with HCs (one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc tests).

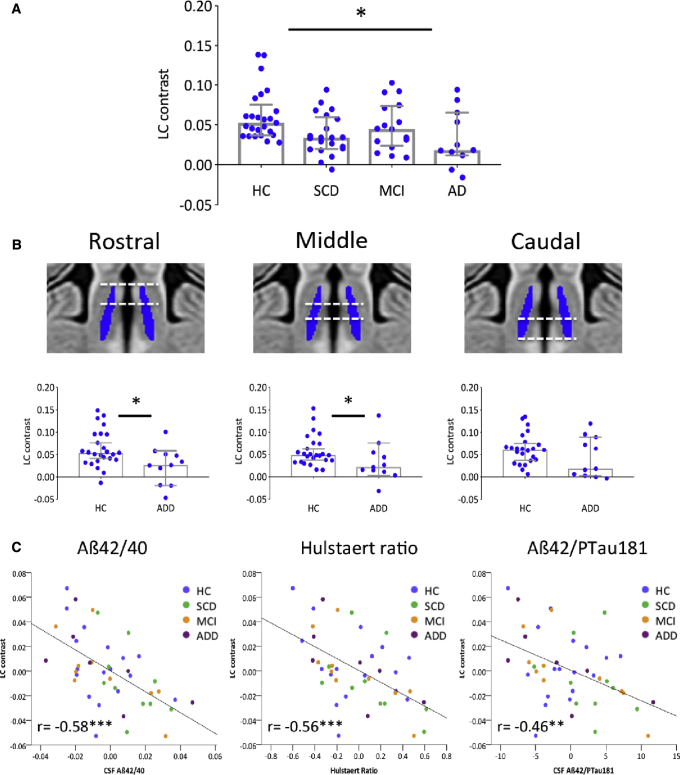

3.2. Locus coeruleus contrast measures

MRI data from 73 individuals are presented of which 42 individuals (16 HCs and 12 SCD, 8 MCI, and 6 ADD patients) were from MRI scanning site 1 and 31 individuals (9 HCs and 9 SCD, 8 MCI, and 5 ADD patients) were from scanning site 2. No significant difference in bilateral LC contrast in HCs and patients with SCD and MCI was observed across sites (all P ≥ .2; Wilcoxon rank-sum test). However, a significant difference in LC MRI contrast in individuals with ADD across sites was found (Z = −2.1; P = .034). In all individuals, significantly higher LC contrast was observed in left compared with right LC hemispheres (Z = −7.0, P < .0001; Wilcoxon signed-ranks test), consistent with previous findings [5]. A significant difference between bilateral LC contrast and diagnosis was observed (χ2 = 9.8, P = .02; Kruskal-Wallis test), whereby LC contrast was significantly lower in patients with ADD than HCs (Z = −2.2, P = .02; post hoc Wilcoxon rank-sum test) as shown in Fig. 1A. Assessment of LC contrast in each rostrocaudal third revealed a significant decline in rostral (Z = −2.3, P = .02) and middle (Z = −2.2, P = .02) but not caudal (Z = −1.3; P = .2) LC contrast in patients with ADD compared with HCs (Fig. 1B). No significant difference in signal intensity in the reference region (P = .3) was observed across groups.

Fig. 1.

(A) LC MRI contrast in 73 participants comprising HCs and individuals with SCD, MCI, and ADD. *P < .05 indicates significant differences in LC MRI contrast compared with HCs (Kruskal-Wallis test with post hoc Wilcoxon rank-sum test). In (B), LC contrast plotted across each LC third in HCs and ADD patients only. * P < .05 indicates significant differences compared with HC (Wilcoxon rank-sum tests). (C) Bootstrapped Pearson's partial correlations between LC contrast and CSF levels of Aβ42/Aβ40, the Hulstaert ratio, and Aβ42/PTau in 44 individuals with CSF biomarker status. Plots displayed are partial residuals controlling for site, age, sex, and diagnosis. Color codes indicate HCs (blue), SCD (green), MCI (orange), and ADD (purple). Asterisks highlight significant correlations (***P < .001; **P < .01). Abbreviations: LC, locus coeruleus; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; HC, healthy controls; SCD, subjective cognitive decline; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; ADD, Alzheimer's disease dementia; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

3.3. Relationship between LC contrast and CSF biomarkers

We established the relationship between LC contrast and CSF biomarkers in 44 participants using bootstrapped Pearson's partial correlations set at 1000 iterations using site, age, sex, and diagnosis as covariates. To minimize the number of tests, bilateral LC contrast values were used for all correlational analyses.

A significant negative correlation between LC contrast and Aβ42/Aβ40 (r = −0.58, 95% CI [−0.74, −0.36], P < .001), the Hulstaert ratio (r = −0.56, 95% CI [−0.74, −0.29], P < .001), Aβ42/PTau181 (r = −0.46, 95% CI [−0.68, −0.15], P = .004), and Aβ42/TTau (r = −0.44, 95% CI [−0.69, −0.13] P = .005) was observed (Fig. 1C). However, no significant relationship between LC contrast and PTau (r = 0.24, 95% CI [−0.11, 0.54], P = .13) or TTau (r = 0.28, 95% CI [−0.07, 0.57], P = .08) was found. All correlations were corrected for multiple comparisons (Bonferroni-corrected P < .05).

To assess the relationship between LC contrast and CSF biomarker status within each LC third, bootstrapped Pearson's partial correlations revealed a significant negative correlation between LC contrast and Aβ42/Aβ40 (r = −0.57, 95% CI [−0.74, −0.35], P < .0001), the Hulstaert ratio (r = −0.57, 95% CI [−0.75, −0.34], P < .0001), Aβ42/PTau181 (r = −0.45, 95% CI [−0.65, −0.20], P = .004), and Aβ42/TTau (r = −0.44, 95% CI [−0.69, −0.17], P = .004) within the rostral third of the LC. A significant negative correlation between LC contrast and Aβ42/Aβ40 (r = −0.52, 95% CI [−0.70, −0.29], P = .001), the Hulstaert ratio (r = −0.48, 95% CI [−0.69, −0.20], P = .002), and Aβ42/PTau181 (r = −0.42, 95% CI [−0.64, −0.12], P = .007) was also observed within the middle LC third, but no significant associations were found in the caudal LC third after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons (all r < −0.32, P > .01). Furthermore, no significant relationship between LC contrast and PTau181 and TTau in any LC third was observed after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

4. Discussion

Consistent with our hypothesis, a significant decrease in LC MRI contrast was observed in patients with ADD compared with healthy older adults, which was regionally confined to the rostral/middle third of the LC. We also identified a direct association between LC contrast and CSF biomarkers of AD, in particular with Aβ42/Aβ40, Aβ42/PTau181, and the Hulstaert ratio; however, no significant association between LC contrast and CSF tau (both PTau and TTau) was observed.

In the CSF, increasing levels of TTau and decreasing levels of Aβ42 provide indirect measures of extracellular amyloid aggregates and intracellular accumulation of hyperphosphorylated tau, respectively [10]. In the sample presented, significantly higher CSF tau and decreased CSF Aβ42/Aβ40 levels were observed in patients with MCI and ADD compared with HCs consistent with more advanced AD pathology. However, differences in LC MRI contrast only significantly correlated with CSF Aβ42/Aβ40 and not CSF tau.

The significant decline in LC MRI contrast in ADD is consistent with previous reports using LC imaging in AD [11], [12]. In addition, the regional AD-related decline in LC MRI contrast observed by Dordevic et al., 2018, is consistent with the reduction in LC MRI contrast in the rostral/middle thirds of the LC in ADD found in this study. It is interesting that the significant decline in LC contrast in the rostral/middle portions of the LC also shows greatest cell loss in AD [13]. In this regard, a positive association with LC contrast and CSF amyloid would have been expected. However, a significant negative association was found whereby LC contrast was higher in individuals with lower CSF Aβ42, which appeared to be predominantly driven by HCs and MCI patients. Thus, one explanation may be that higher LC contrast indicates greater resilience to remain in a HC/MCI stage (as opposed to an ADD stage) at a given level of CSF Aβ. Indeed, protective effects of the LC-noradrenergic system have been described previously [14], [15], [16]; however, this hypothesis remains speculative at this time. In this sample, no significant association between LC contrast and CSF tau was observed, which may be due to the limited sample size presented. Thus, additional analyses using larger sample sizes are required to ascertain how AD pathology may influence LC contrast.

In conclusion, these preliminary findings demonstrate a regional decline in LC MRI contrast in ADD and provide first evidence for a direct association between changes in LC MRI contrast and CSF biomarkers of AD. The significant negative relationship between LC contrast and CSF Aβ42/Aβ40 suggests differences in LC neuromelanin identified using T1-weighted FLASH imaging may be useful to investigate LC-related vulnerability and resilience in the face of Alzheimer's pathology.

Research in context.

-

1.

Systematic review: A literature search on PubMed revealed three studies investigating locus coeruleus (LC) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contrast changes in Alzheimer's disease (AD). However, no study to date had investigated the relationship between LC MRI contrast and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers of AD.

-

2.

Interpretation: We observed reduced MRI contrast in the rostral/middle third but not caudal third of the LC in AD dementia compared with healthy controls consistent with AD neuropathology. Changes in LC MRI contrast negatively correlated with levels of CSF amyloid.

-

3.

Future direction: Additional analyses using larger sample sizes are required to ascertain how the clinical progression of AD pathology may influence LC MRI contrast.

Acknowledgments

The study was funded by the German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (Deutsches Zentrum für Neurodegenerative Erkrankungen [DZNE]), reference number BN012. MB is supported by the Human Brain Project (SPC WP 3.3.1).

References

- 1.Braak H., Thal D.R., Ghebremedhin E., Del Tredici K. Stages of the pathologic process in Alzheimer disease: Age categories from 1 to 100 years. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2011;70:960–969. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e318232a379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sasaki M., Shibata E., Tohyama K., Takahashi J., Otsuka K., Tsuchiya K. Neuromelanin magnetic resonance imaging of locus ceruleus and substantia nigra in Parkinson's disease. Neuroreport. 2006;17:1215–1218. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000227984.84927.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keren N.I., Lozar C.T., Harris K.C., Morgan P.S., Eckert M.A. In vivo mapping of the human locus coeruleus. Neuroimage. 2009;47:1261–1267. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clewett D.V., Lee T.-H., Greening S., Ponzio A., Margalit E., Mather M. Neuromelanin marks the spot: identifying a locus coeruleus biomarker of cognitive reserve in healthy aging. Neurobiol Aging. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Betts M.J., Cardenas-Blanco A., Kanowski M., Jessen F., Düzel E. In vivo MRI assessment of the human locus coeruleus along its rostrocaudal extent in young and older adults. Neuroimage. 2017;163:150–159. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu K.Y., Acosta-Cabronero J., Cardenas-Blanco A., Loane C., Berry A.J., Betts M.J. In vivo visualization of age-related differences in the locus coeruleus. Neurobiol Aging. 2019;74:101–111. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2018.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hämmerer D., Callaghan M.F., Hopkins A., Kosciessa J., Betts M., Cardenas-Blanco A. Locus coeruleus integrity in old age is selectively related to memories linked with salient negative events. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2018;115:2228–2233. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1712268115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jessen F., Spottke A., Boecker H., Brosseron F., Buerger K., Catak C. Design and first baseline data of the DZNE multicenter observational study on predementia Alzheimer's disease (DELCODE) Alzheimers Res Ther. 2018;10 doi: 10.1186/s13195-017-0314-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hulstaert F., Blennow K., Ivanoiu A., Schoonderwaldt H.C., Riemenschneider M., Deyn P.P.D. Improved discrimination of AD patients using -amyloid(1-42) and tau levels in CSF. Neurology. 1999;52 doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.8.1555. 1555–1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blennow K., Hampel H., Weiner M., Zetterberg H. Cerebrospinal fluid and plasma biomarkers in Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2010;6:131–144. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takahashi J., Shibata T., Sasaki M., Kudo M., Yanezawa H., Obara S. Detection of changes in the locus coeruleus in patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease: High-resolution fast spin-echo T1-weighted imaging: Locus coeruleus in cognitive impairment. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2015;15:334–340. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dordevic M., Müller-Fotti A., Müller P., Schmicker M., Kaufmann J., Müller N.G. Optimal Cut-Off Value for Locus Coeruleus-to-Pons intensity ratio as clinical biomarker for Alzheimer's Disease: A pilot study. J Alzheimers Dis Rep. 2017;1:159–167. doi: 10.3233/ADR-170021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Theofilas P., Ehrenberg A.J., Dunlop S., Alho A.T., Nguy A., Paraizo Leite R.E. Locus coeruleus volume and cell population changes during Alzheimer's disease progression: A stereological study in human postmortem brains with potential implication for early-stage biomarker discovery. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13:236–246. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.06.2362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bowden V.M. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 1992;268:1473. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Betts M.J., Ehrenberg A.J., Hämmerer D., Düzel E. Commentary: Locus coeruleus ablation exacerbates cognitive deficits, neuropathology, and lethality in P301S Tau Transgenic Mice. Front Neurosci. 2018;12 doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.00401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rorabaugh J.M., Chalermpalanupap T., Botz-Zapp C.A., Fu V.M., Lembeck N.A., Cohen R.M. Chemogenetic locus coeruleus activation restores reversal learning in a rat model of Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2017 doi: 10.1093/brain/awx232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]