Abstract

Sponges host cryptic endobionts within their network of canals, with representatives from all major animal phyla. This study investigates the endobiotic community of four sponge species (Spongia officinalis, Sarcotragus spinosulus, Ircinia cf. variabilis and Ircinia oros) that were collected during scientific trawl surveys in the coastal area of Cyprus. Moreover, it examines the endobiotic community composition of S. spinosulus in relation to sponges' volume, and various environmental variables. In general, the four sponge endobiotic communities were similar; S. officinalis had a significantly different community composition to I. cf. variabilis and I. oros. The phyla identified followed the general infauna composition of sponges, with the relative abundances of the dominant phyla, Arthropoda and Annelida, ranging from 66.9 - 83.7 % and 4.8–26.5 %, respectively. The highest intensity (I) corresponded to the isopod Cymodoce truncata in S. officinalis (I = 85 individuals/sponge) and S. spinosulus (I = 27.2 individuals/sponge). A general linear model also suggested that distance from shore influenced the total endobiotic abundance of S. spinosulus. This is the first sponge endobiotic community baseline study that covers the whole coastal area of the Republic of Cyprus and is particularly important due to potential changes of Eastern Mediterranean endobiotic communities due to the invasion through the Suez Canal of non-indigenous species.

Keywords: Ecology, Environmental science

1. Introduction

Sponges comprise a major part of the global marine benthos (Taylor et al., 2007; Fan et al., 2012). They increase environmental heterogeneity and can act as microhabitats for vertebrates, invertebrates and a rich microbiome (Abdo, 2007; Fiore and Jutte, 2010; Pita et al., 2018). They are also contemplated as important ecological contributors in reef habitats as they perform several vital ecosystem functions for both the benthic and pelagic environments, compete for space with other benthic organisms, as well as support and enhance biodiversity through bottom-up coupling (Brown et al., 1995; Rutzler, 2003; Trussell et al., 2006; de Goeij et al., 2013; Webster and Thomas, 2016). As autogenic ecosystem engineers, they assist in the survival of productive ecosystems in low nutrient areas like the ultra-oligotrophic regions of Eastern Mediterranean (Gerovasileiou and Voultsiadou, 2012; Miller et al., 2012; Rix, 2015).

Sponge endobiotic communities have been described and investigated extensively around the world, including within regions of Southern US (i.e. Brazil and Argentina), Antarctica, Australia, the Faroe Islands and the Mediterranean Sea (Klitgaard, 1995; Ribeiro et al., 2003; Abdo, 2007; Fiore and Jutte, 2010; Schejter et al., 2012; Kersken et al., 2014; Gerovasileiou et al., 2016). Sponges found in these locations tend to primarily comprise an endobiotic community with organisms from the phyla Arthropoda, Annelida, Echinodermata, Mollusca and Chordata (Klitgaard, 1995; Ribeiro et al., 2003; Abdo, 2007; Fiore and Jutte, 2010; Schejter et al., 2012; Kersken et al., 2014; Gerovasileiou et al., 2016).

Even though the Mediterranean is considered an ecological hotspot for sponge biodiversity with a total of 681 species recorded (48 % of them endemic; Coll et al., 2010), there are still regions and habitats within the Mediterranean, and especially the eastern Levantine Basin (e.g. deep-sea habitats and submarine caves) that need further investigation (Pansini and Longo, 2003; Voultsiadou, 2005, 2009; Coll et al., 2010; Gerovasileiou and Voultsiadou, 2012). More precisely, over the years, the Levantine Sea has had only a handful of investigations concentrating on sponges and their endobiotic community compositions, with only one of these just briefly considering the coastal area of Cyprus (Özcan and Katağan, 2011; Pavloudi et al., 2016). The most studied aspects of Mediterranean sponges are ecology (46.6 % of available publications), taxonomy (24.7 %) and molecular biology (17 %) (Becerro, 2009).

Koukouras et al. (1996), indicated that endobiotic sponge communities can be either similar or unique between sponge species, as well as that the volume of the sponge can affect the presence, abundance and richness of associated sponge fauna. Furthermore, endobiotic associates of the sponges A. oroides, Petrosia ficiformis, Ircinia variabilis and A. aerophoba, in the North Aegean Sea, were found not to be host specific (Koukouras et al., 1992). This leaves the question of whether the endobiotic communities of the sponge species in Cyprus are similar or different, and whether they are affected by their associated fauna, the host, the environmental variables, or a combination of these factors.

Due to the crucial role sponges have within ecosystems, the more we know about their ecology, their associated communities, and the biotic and abiotic factors that affect their ability to thrive, the better our understanding can improve on how they potentially assist the increased abundance and biodiversity of an area. This is especially important for the Eastern Mediterranean because, even though it is an ultra-oligotrophic region, it once was one of the most productive sponge banks (Perez and Vacelet, 2014). Moreover, Cyprus has had a long history of sponge fishery and harvest, activities that have increasingly become more difficult due to the decreased population of commercial sponges from over-exploitation and global warming (Economou & Konteatis 1988, 1990; Perez and Vacelet, 2014).

This baseline study was conducted to tackle the lack of data on sponges and their associated endobiotic communities within the coastal area of Cyprus, as well as their interaction with their environment. In this paper the endobiotic communities of four sponge species are compared as well as the relation between the endobiotic communities with the sponge species, sponge morphology and abiotic factors (depth, salinity, temperature and distance from the shore).

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study area

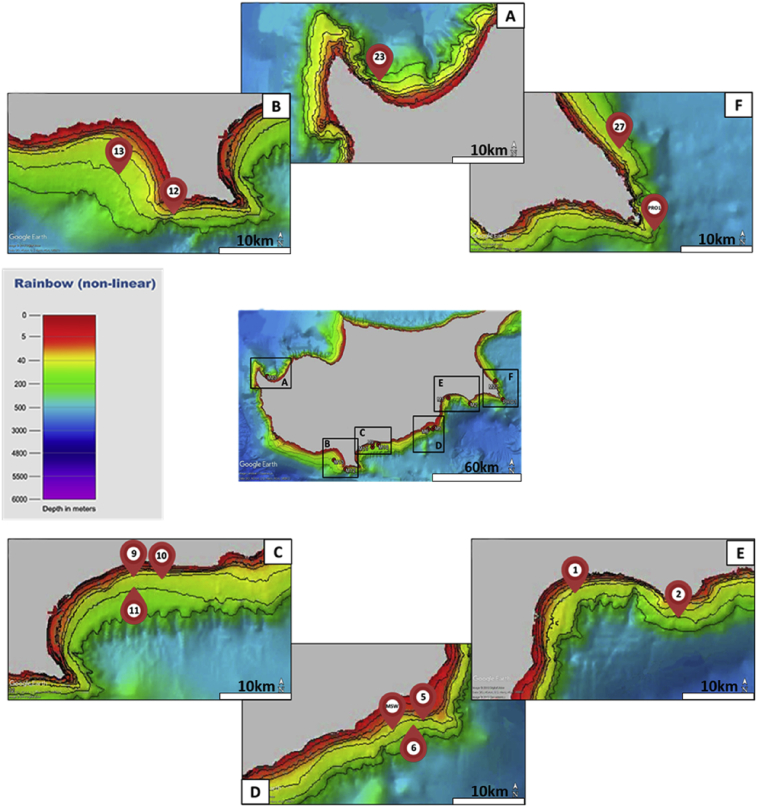

The sponges (n = 43) were collected in the Republic of Cyprus using the Trawler R/V ‘MEGALOHARI’, during two scientific trawler surveys: August 2015 and June 2016 MedITS (Mediterranean International Bottom Trawling Survey) and June 2016 PROTOMEDEA (Protecting Mediterranean East) project (Fig. 1). The samples were retrieved from a depth of 45–100 meters, at a towing speed of 3 knots and duration 30 minutes. The trawler specifications complied with the ‘International Bottom Trawl Survey in the Mediterranean’, Instruction Manual, Version 8 (Spedicato-NB, 2016). One sample was also collected by scuba diving at 43 m depth during a PROTOMEDEA survey at the Mazotos ancient ship wreck (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Haul locations from which sponges were obtained within the coastal area of the Republic of Cyprus; M: 2015–2016 MedITS; PRO: 2016 PROTOMEDEA; MSW: the Mazotos ship wreck (Mean Depth Rainbow Coloured Ramp attained by EMODnet Bathymetry Consortium, 2018).

2.2. Sponge Collection and Identification

Due to limited time available between hauls, only 43 sponges in total were collected and inspected. Scaled top and side-view photos of each sponge were taken in order to calculate maximum length, width and height (cm). These measurements were then used to calculate the approximate volume (cm3) of the sponge using the most appropriate formula. A small section of sponge was cut and preserved in 70 % ethanol for later analysis and identification. The remaining sponge was sliced into thin equal strips (2 ± 0.5 cm), and the endobionts (those visible to the eye, >1 mm) were carefully removed with forceps and preserved in 70 % ethanol.

The sponge and associate organism identification was achieved to the lowest taxonomic resolution using the standard identification method and an assortment of identification keys, research papers and online databases (van Soest et al., 1912, Day, 1967, Demetropoulos, 1976, Abel et al., 1986, Tornaritis, 1987, Ruffo, 1989, van Soest et al., 1994a,b, Debelius, 1999, Hooper and Van Soest, 2002, Hooper, 2003, van Soest, 2003, Fauvel, 2004, Pillai, 2009, Fiore and Jutte, 2010, Manconi et al., 2013, San Martín and Worsfold, 2015).

2.3. Environmental data

Salinity was recorded at the end of each haul using a CTD (SBE 19plus Thermosalinometer), while a MiniCTD (SBE 39 Temperature-Pressure Recorder) attached to the trawler-net, logged the depth (m) and temperature (°C). Additionally, the average distance from the shore was calculated using the start and end coordinates of each haul.

2.4. Statistical analysis

2.4.1. Description and comparison of different sponge associated communities

Percentage of relative abundance (R.A.) of the endobiotic organisms were calculated both at the Phylum and Family level. Prevalence (P) and Intensity (I) of each phylum were also calculated to determine their encounter rate and average number of individuals per host sponge species respectively, by using the following formulas:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

Species Richness, Shannon-Wiener Diversity Index (H′), Pielou evenness (J′) and Species Accumulation Curves were calculated per sponge species. Additionally, an analysis of similarity (ANOSIM) based on Bray-Curtis similarity was conducted in ‘PastV3’ (Version 3.20), to compare the endobiotic community between the sponge species, where initially an overall analysis was performed on all sponges, followed by pairwise tests to identify similarities between individual species. A similarity percentage analysis (SIMPER) was then used to identify the species contributing to the most differences between the sponges. Additionally, a Venn diagram was created to show the distribution of the unique endofauna sponge associates, versus those that were common in more than one species. A permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) was also conducted in ‘PastV3’ to investigate the relationship between the endobiotic community of different sponge species and year.

2.4.2. Sarcotragus spinosulus associated community abundance

A General Linear Model (GLM) was fitted to the data in R (Version 0.98.1091), to examine if maximum depth, and average salinity, temperature and distance from the shore had any significant effect on the total endobiotic abundance of the sponge Sarcotragus spinosulus. Similarly, a GLM was also used to investigate whether volume had a significant effect on the total endobiotic abundance of S. spinosulus. Variables were only tested on S. spinosulus as it was the only species with a large enough sample pool. This was accomplished by first testing the model for normality of residuals (histogram and Q-Q plot), independence of variance, homoscedasticity and collinearity (VIF). Significance of the variables, and their interactions, was determined using the F-ratio and the P-values (significance level = 0.05) calculated by ANOVA.

The relationship between the environmental variables and total endobiotic abundance of S. spinosulus was calculated using Pearson's correlation coefficient (r) in Microsoft Excel 2010. The same procedure was followed for the volume.

3. Results

3.1. Endobiotic sponge associated community descriptions

Forty four sponge specimens in total were inspected: Spongia officinalis (survey 2015 = 2, survey 2016 = 4), S. spinosulus (2015 = 11, 2016 = 11), Ircinia cf. variabilis (survey 2016 = 9) and Ircinia oros (2015 = 2, 2016 = 5).

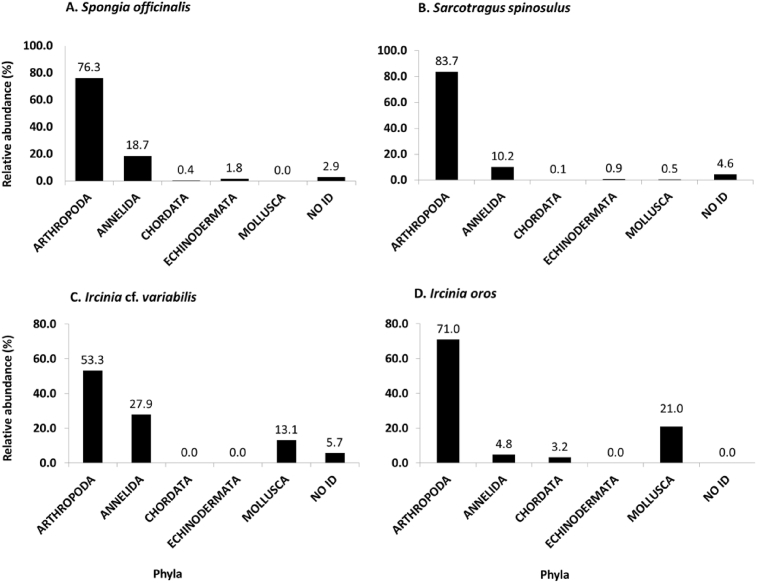

The phylum with the highest relative abundance (R.A.) in all four sponge species was Arthropoda (Families: Alpheidae and Sphaeromatidae), followed by Annelida (Families: Nereididae and Terebellidae; except in I. oros) (Table 1 and Fig. 2.). A small percentage of organisms were too damaged to be identified.

Table 1.

Prevalence (P), and Intensity (I) of the endobiotic organisms inhabiting the four sponge species; Spongia officinalis, Sarcotragus spinosulus, Ircinia cf. variabilis and Ircinia oros, collected within the coastal area of Cyprus. ‘+’ = indicates presence of the specific gender within the species.

| Species |

Spongia officinalis |

Sarcotragus spinosulus |

Ircinia cf. variabilis |

Ircinia oros |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | I | P | I | P | I | P | I | |

| Annelida | ||||||||

| Clitellata | ||||||||

| Rhynchobdellida | ||||||||

| Stibarobdella moorei (Oka, 1910) | 4.6% | 1 | ||||||

| Polychaeta | ||||||||

| Amphinomida | ||||||||

| Hermodice carunculata (Pallas, 1766) | 4.6% | 1 | ||||||

| Eunicida | ||||||||

| Lysidice ninetta Audouin & H Milne Edwards, 1833 | 14.3% | 1 | ||||||

| Marphysa sanguinea (Montagu, 1813) | 16.7% | 1 | 4.6% | 2 | 11.1% | 1 | ||

| Phyllodocida | ||||||||

| Phyllodocida sp. 1 | 16.7% | 5 | 22.7% | 1.6 | ||||

| Bylgides groenlandicus (Malmgren, 1867) | 9.1% | 1.5 | ||||||

| Hediste diversicolor (O.F. Müller, 1776) | 83.3% | 8 | 59.1% | 3.9 | 66.7% | 3.3 | 28.6% | 1 |

| Lepidasthenia elegans (Grube, 1840) | 4.6% | 1 | ||||||

| Odontosyllis sp. 1 | 11.1% | 1 | ||||||

| Hesionidae sp. 1 | 4.6% | 1 | ||||||

| Syllis armillaris (O.F. Müller, 1776) | 11.1% | 2 | ||||||

| Sabellida | ||||||||

| Sabella pavonina Savigny, 1822 | 11.1% | 1 | ||||||

| Serpula cf. vermicularis (Linnaeus, 1767) | 11.1% | 1 | ||||||

| Vermiliopsis infundibulum (Phillipi, 1844) | 4.6% | 1 | 11.1% | 1 | ||||

| Terebellida | ||||||||

| Eupolymnia nesidensis (Delle Chiaje, 1828) | 11.1% | 3 | ||||||

| Nicolea zostericola (Örsted, 1844) | 50.0% | 2 | 13.6% | 2.7 | 22.2% | 1 | ||

| Terebellidae sp. 1 | 4.6% | 2 | ||||||

| Arthropoda | ||||||||

| Malacostraca | ||||||||

| Amphipoda | ||||||||

| Aristias cf. tumidus (Kroyer, 1846) | 16.7% | 3 | 11.1% | 1 | ||||

| Colomastix pusilla (Grube, 1861) | 16.7% | 3 | 13.6% | 4 | ||||

| Dexamine spiniventris (Costa, 1853) | 4.6% | 1 | ||||||

| Quadrimaera inaequipes (A. Costa, 1857) | 13.5% | 5.7 | ||||||

| Decapoda | ||||||||

| Athanas nitescens (Leach, 1813) | 66.7% | 2.5 | 13.6% | 2 | ||||

| Galathea intermedia Lilljeborg, 1851 | 16.7% | 2.5 | 18.2% | 1.3 | ||||

| Pandalina brevirostris (Rathke, 1843) | 9.1% | 2.5 | ||||||

| Pilumnus hirtellus (Linnaeus, 1761) | 66.7% | 4 | 54.6% | 2.8 | 33.3% | 3.3 | 14.3% | 1 |

| Pilumnus hirtellus – FEMALE | + | 3.3 | + | 2 | + | 1 | ||

| Pilumnus hirtellus – MALE | + | 1.5 | + | 2 | + | 1 | + | 1 |

| Synalpheus gambarelloides (Nardo, 1847) | 59.1% | 22.4 | 66.7% | 9.5 | 100% | 6.1 | ||

| Isopoda | ||||||||

| Anilocra physodes (Linnaeus, 1758) | 4.6% | 1 | ||||||

| Cymodoce truncata (Leach, 1814) | 16.7% | 85 | 40.9% | 27.2 | 33.3% | 3.7 | ||

| Cymodoce truncata – FEMALE | + | 45.5 | + | 10.9 | + | 3 | ||

| Cymodoce truncata – MALE | + | 39.5 | + | 18.4 | + | 2 | ||

| Gnathia phallonajopsis Monod, 1925 | 16.7% | 5 | 22.7% | 5 | 22.2% | 1 | ||

| Gnathia phallonajopsis – FEMALE | + | 5 | + | 2.2 | ||||

| Gnathia phallonajopsis – MALE | + | 2.8 | + | 1 | ||||

| Chordata | ||||||||

| Actinopterygii | ||||||||

| Bony fish sp. 1 | 16.7% | 1 | ||||||

| Perciformes | ||||||||

| Spicara smaris (Linnaeus, 1758) | 14.3% | 2 | ||||||

| Ascidiacea | ||||||||

| Stolidobranchia | ||||||||

| Herdmania momus (Savigny, 1816) | 4.6% | 1 | ||||||

| Echinodermata | ||||||||

| Asteroidea | ||||||||

| Forcipulatida | ||||||||

| Marthasterias glacialis (Linnaeus, 1758) | 4.6% | 1 | ||||||

| Ophiuroidea | ||||||||

| Ophiurida | ||||||||

| Amphiura chiajei (Forbes, 1843) | 16.7% | 5 | 13.3% | 2 | ||||

| Mollusca | ||||||||

| Bivalvia | ||||||||

| Limida | ||||||||

| Lima lima (Linnaeus, 1758) | 14.3% | 12 | ||||||

| Arcida | ||||||||

| Barbatia barbata (Linnaeus, 1758) | 13.3% | 1 | 11.1% | 1 | 14.3% | 1 | ||

| Gastropoda | ||||||||

| Neogastropoda | ||||||||

| Raphitoma contigua (Monterosato, 1884) | 4.6% | 1 | ||||||

Fig. 2.

Relative abundances of all phyla established within the four sponge species collected during the Mediterranean International Bottom Trawling Survey (MedITS) and Protecting Mediterranean East (PROTOMEDEA) projects, in the coastal area of Cyprus. A.Spongia officinalis, B.Sarcotragus spinosulus, C.Ircinia cf. variabilis and D.Ircinia oros.

The Arthropoda species, Pilumnus hirtellus (Decapoda) and Cymodoce truncata (Isopoda) had both genders present in all sponge species, except in I. oros which had only one male. Additionally, Gnathia phallonajopsis (Isopoda) had both males and females within S. spinosulus, only females in S. officinalis and one male in I. cf. variabilis. Furthermore, there were a total of seven gravid P. hirtellus (four in S. officinalis, and three in S. spinosulus), four C. truncata (in S. officinalis), 89 Synalpheus gambarelloides (Decapoda; 51 in S. spinosulus, 23 in I. cf. variabilis, and 15 I. oros), one Pandalina brevirostris (Decapoda; in S. spinosulus), and one Galathea intermedia (Decapoda; in S. spinosulus) within the samples.

The dominant organisms within the sponges S. spinosulus, I. cf. variabilis and I. oros was the snapping shrimp S. gambarelloides, followed by the polychaete Hediste diversicolor (Phyllodocida). In S. officinalis, S. gambarelloides was absent and the dominant species was H. diversicolor.

The endobiotic species with the highest intensity included C. truncata (in S. officinalis and S. spinosulus), S. gambarelloides (in S. spinosulus, I. cf. variabilis and I. oros), and the bivalve Lima lima (Limida; in I. oros).

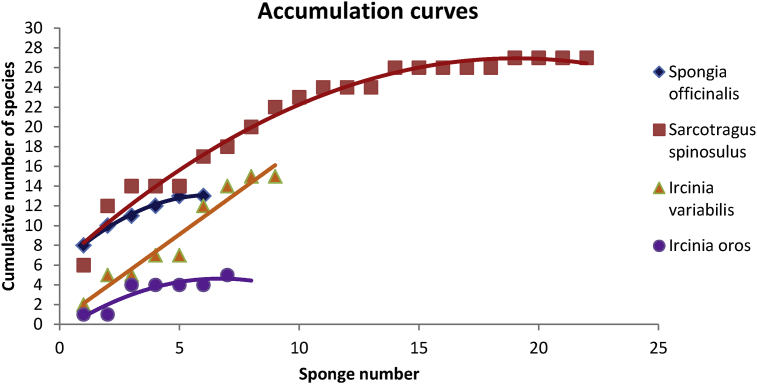

3.2. Species richness, diversity, evenness and accumulation curve

The highest species richness (n) and diversity (H′) were obtained by S. spinosulus (n = 30; H’ = 1.74), followed by Ircinia cf. variabilis (n = 15; H’ = 1.69), S. officinalis (n = 14; H’ = 1.38), and lastly I. oros (n = 5; H’ = 0.93). Additionally, the endobiotic evenness for the sponges I. oros (J’ = 0.52), S. spinosulus (J’ = 0.53) and S. officinalis (J’ = 0.54) was around 0.5. The species that displayed the most evenness was Ircinia cf. variabilis (J' = 0.62).

The species accumulation curves of S. spinosulus and I. oros (Fig. 3) demonstrated that enough samples were obtained for an accurate endobiotope description. However, S. officinalis and Ircinia cf. variabilis lacked samples for a complete endobiotic community account.

Fig. 3.

Species Accumulation Curves for the four studied sponge species; Sarcotragus spinosulus (red), Spongia officinalis (blue), Ircinia cf. variabilis (orange) and Ircinia oros (purple), within the coastal area of the Republic of Cyprus.

3.3. Similarities amongst sponge associated communities

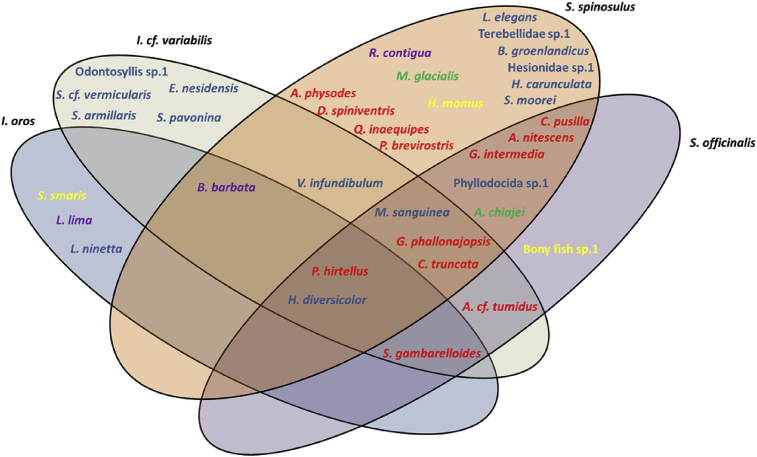

The endobiotic community composition was similar between the four sponge species (ANOSIM; overall R = 0.15, p = 0.014; Table 2). Furthermore, the pairwise comparisons (pw) indicated that the sponge S. officinalis had a relatively different endobiotic community in relation to I. cf. variabilis (pw; R = 0.22, p = 0.040; Table 2), and an almost completely different community composition to the species I. oros (pw; R = 0.93, p = 0.0004; Table 2). The SIMPER analysis indicate that the associated endobiotic species that most contributed to the dissimilarity between S. officinalis and I. cf. variabilis, and S. officinalis and I. oros were C. truncata (27.46 and 22.22 %), S. gambarelloides (19.78 and 22.47 %) and H. diversicolor (19.94 and 21.67 %). Additionally, S. spinosulus was the only species that had several mutual organisms with all four sponge species (Fig. 4).

Table 2.

Summary of analysis of similarity (ANOSIM) indicating both the R-statistic and p-values for the overall test (similarity of the endobiotic community of the four sponges species), and pairwise test comparing the four sponge species between themselves. ‘*’ = indicates 95% significance.

| Sponge species | R-statistic | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Overall | 0.1534 | 0.0139* |

| S. spinosulus vs S. officinalis | 0.1556 | 0.0897 |

| S. spinosulus vs I. cf. variabilis | 0.0011 | 0.4482 |

| S. spinosulus vs I. oros | 0.1823 | 0.0586 |

| S. officinalis vs I. cf. variabilis | 0.2211 | 0.0403* |

| S. officinalis vs I. oros | 0.9253 | 0.0004* |

| I. cf. variabilis vs I. oros | 0.0666 | 0.1795 |

Fig. 4.

Venn diagram illustrating the distribution of the endobiotic associates within the four sponge species; Sarcotragus spinosulus, Spongia officinalis, Ircinia cf. variabilis and Ircinia oros. Shown are the phyla Annelida (blue), Arthropoda (red), Chordata (yellow), Echinodermata (green) and Mollusca (purple).

The analysis also illustrated that the endobiotic associated community of the sponges was affected by sponge species (PERMANOVA; F = 1.46, p = 0.0005; Table 3), but not the year (PERMANOVA; F = 1.01, p = 0.09; Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) for the endobiotic community composition of the sponge samples; S. spinosulus, S. officinalis, I. cf. variabilis and I. oros, and Year. ‘*’ = indicates 95% significance.

| d.f. | F-value | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sponge | 3 | 1.456 | 0.0005* |

| Year | 1 | 1.013 | 0.0863 |

| Interaction | 3 | -4.024 | 0.3823 |

| Residuals | 35 |

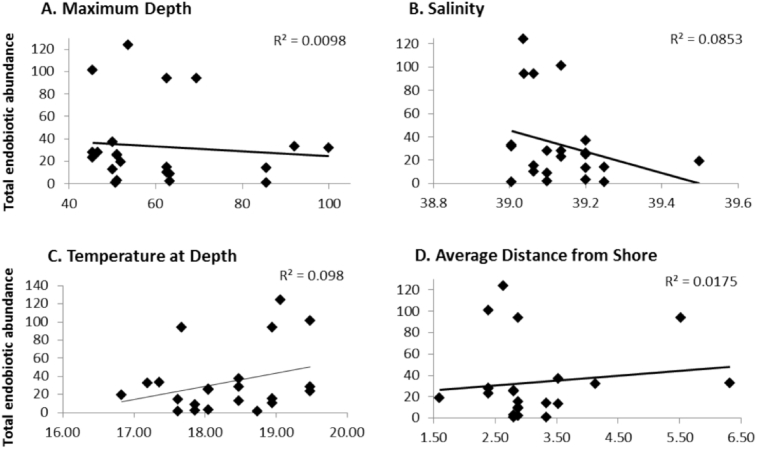

3.4. Total endobiotic abundance of Sarcotragus spinosulus, in relation to environmental variables

Distance from the shore (GLM; F1,9 = 5.68, p = 0.041; Table 4) significantly affected the endobiotic abundance of S. spinosulus, while depth, salinity and temperature didn't (GLM, Depth; F1,9 = 5.05, p = 0.051, Salinity; F1,9 = 0.47, p = 0.51, Temperature; F1,9 = 1.32 p = 0.28; Table 4). Moreover, total endobiotic abundance had a very weak negative correlation with maximum depth (r2 = -0.10), and a weak relationship with salinity (r2 = -0.40; Fig. 5A & B). In contrast, average temperature and distance from the shore displayed a weak (r2 = 0.31), and a very weak positive (r2 = 0.13) relationship with total abundance respectively (Fig. 5C & D).

Table 4.

Summary of the General linear model (GLM) fitted to the data to analyse the relationship between the environmental variables in relation to the total endobiotic abundance of the sponge Sarcotragus spinosulus. Depth = Maximum depth; Distance = Distance from the shore; Temperature = Average temperature at depth and Salinity; ‘*’ = indicates 95% significance.

| d.f | F-value | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depth | 1 | 5.0462 | 0.05131 |

| Distance | 1 | 5.6823 | 0.04097* |

| Salinity | 1 | 0.4680 | 0.51115 |

| Temperature | 1 | 1.3261 | 0.27918 |

| Depth: Distance | 1 | 0.7316 | 0.41455 |

| Depth: Salinity | 1 | 8.9508 | 0.01516* |

| Distance: Salinity | 1 | 0.1696 | 0.69006 |

| Depth: Temperature | 1 | 0.9568 | 0.35355 |

| Distance: Temperature | 1 | 0.0030 | 0.95747 |

| Salinity: Temperature | 1 | 7.4930 | 0.02295* |

| Depth: Distance: Salinity | 1 | 0.5333 | 0.483781 |

| Depth: Distance: Temperature | 1 | 3.2584 | 0.10454 |

| Residuals | 9 |

Fig. 5.

Correlation between the total endobiotic abundance of Sarcotragus spinosulus and the environmental variables A. Maximum depth, B. Salinity, C. Temperature at depth and D. Average distance from the shore.

The variable interaction effect (Table 4) presented an interaction between depth and salinity (GLM, F1,9 = 8.95, p = 0.015), and one between salinity and temperature (GLM, F1,9 = 7.49, p = 0.023).

3.5. Total sponge endobiotic abundance in relation to sponge volume

A significant relationship between sponge volume and total endobiont abundance (GLM: F1,25 = 14.3, p = 0.0009; Table 5), but not species (GLM: F3,25 = 2.77, p = 0.063) was found. Additionally, the GLM produced a positive correlation (r2 = 0.48) between total endobiotic abundance and volume. The endobiotic phyla abundance increased proportionally to the percentage of the sponge that they already inhabited i.e. at a volume of 591.29 cm3 the highest abundance was obtained by the Arthropoda phylum (n = 10), followed by the Annelida (n = 5); at a volume of 9599.44 cm3 the highest abundance was obtained again by the Arthropoda (n = 89), followed by the Annelida (n = 13) (Table 6).

Table 5.

Summary of the General linear model (GLM) fitted to the data to analyse the relationship between the volume and “Total endobiotic community abundance” of the sponge samples.

| d.f | F-value | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Species | 3 | 2.7657 | 0.0628576 |

| Volume | 1 | 14.3295 | 0.0008578* |

| Residuals | 25 |

Table 6.

Sponge samples collected during the Mediterranean International Bottom Trawling Survey (MedITS) and Protecting Mediterranean East (PROTOMEDEA) projects, in the coastal area of the Republic of Cyprus, along with their corresponding dimensions (maximum length, width and height), approximate volume and their total endobiotic abundance.

| Sample name | Sponge Species | Sponge length (cm) | Sponge width (cm) | Sponge height (cm) | Approximate volume (cm3) | Total Endobiotic Abundance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1SP1-M16 | S. officinalis | 30.51 | 22.60 | 15.50 | 5596.04 | 81 |

| H1SP3-M16 | S. officinalis | 22.20 | 17.26 | 10.30 | 2066.47 | 17 |

| H1SP4-M16 | S. officinalis | 42.17 | 32.35 | 13.50 | 9642.96 | 150 |

| H10SP2- M16 | S. officinalis | 15.50 | 12.75 | 9.50 | 983.02 | 14 |

| H1SP2-M16 | S. spinosulus | 23.03 | 20.03 | 13.10 | 3164.06 | 124 |

| H6SP3-M16 | S. spinosulus | 35.10 | 27.00 | 20.50 | 10172.40 | 94 |

| H9SP2-M16 | S. spinosulus | 36.48 | 29.05 | 17.30 | 9599.44 | 189 |

| H9SP4-M16 | S. spinosulus | 20.42 | 15.85 | 11.20 | 1898.02 | 23 |

| H9SP5-M16 | S. spinosulus | 23.04 | 20.99 | 14.80 | 3747.62 | 28 |

| H10SP3-M16 | S. spinosulus | 17.53 | 14.32 | 8.50 | 1117.23 | 94 |

| H10SP4-M16 | S. spinosulus | 12.70 | 11.60 | 7.60 | 591.29 | 10 |

| H10SP5-M16 | S. spinosulus | 10.68 | 10.00 | 8.55 | 478.12 | 15 |

| H11SP1-M16 | S. spinosulus | 24.84 | 23.43 | 16.50 | 5028.13 | 32 |

| H13SP1-M16 | S. spinosulus | 40.50 | 27.27 | 10.20 | 5898.46 | 46 |

| H1SP5-M16 | I. cf. variabilis | 17.18 | 13.02 | 9.40 | 1100.93 | 13 |

| H7SP2-M16 | I. cf. variabilis | 9.44 | 8.30 | 8.10 | 332.30 | 8 |

| H9SP3-M16 | I. cf. variabilis | 13.95 | 12.86 | 9.40 | 882.96 | 22 |

| H10SP1-M16 | I. cf. variabilis | 19.29 | 16.70 | 10.70 | 1804.81 | 33 |

| H10SP6-M16 | I. cf. variabilis | 11.80 | 11.00 | 4.80 | 326.22 | 8 |

| H10SP7-M16 | I. cf. variabilis | 11.20 | 10.30 | 4.30 | 259.73 | 10 |

| H11SP2-M16 | I. cf. variabilis | 9.48 | 8.60 | 4.60 | 196.36 | 6 |

| H6SP2-M16 | I. oros | - | 11.00 | 28.06 | 2666.63 | 16 |

| H7SP1-M16 | I. oros | - | 5.52 | 38.15 | 912.98 | 6 |

| H1SP4-M16 | I. oros | - | 6.48 | 29.17 | 962.00 | 2 |

| H1SP5-M16 | I. oros | - | 6.00 | 12.00 | 339.29 | 1 |

| DIVESP1-M16 | I. oros | - | 3.00 | 11.70 | 82.70 | 4 |

4. Discussion

The four sponge species follow the general faunal composition (Annelida, Arthropoda, Chordata, Echinodermata and Mollusca) that usually forms the infaunal community of sponges worldwide (Ribeiro et al., 2003; Abdo, 2007; Fiore and Jutte, 2010; Gerovasileiou et al., 2016). The same synthesis at the phylum level was also found for the communities associated with two species of Haliclona sp. in Southwest Australia, and the sponges Agelas oroides and Aplysina aerophoba in the North Aegean Sea (Abdo, 2007; Gerovasileiou et al., 2016). Moreover, the sponge Mycale microsigmatosa from Southeast Brazil, had an associated endobiotic community that comprised species mainly from the phyla Crustacea, Polychaeta, Mollusca, Cnidarian and Echinodermata (Ribeiro et al., 2003).

The dominant phylum (R.A. > 50%) within all sponge species was Arthropoda, and more specifically the obligate sponge-dweller shrimp Synalpheus gambarelloides (Duffy et al., 2000). Similarly, S. gambarelloides (R.A. = 86.6%) was the dominant organism in the sponge Sarcotragus muscarum in a study conducted in Turkey - Levantine Basin (Özcan and Katağan, 2011). The high abundance of S. gambarelloides could be explained by its bigger size, which possibly provides it with a competitive advantage of obtaining more space and nutrients (Özcan and Katağan, 2011). The same concept can probably also be applied to the isopod Cymodoce truncata, where in the absence of the Synalpheus shrimp, its intensity was observed to be three times higher.

The Arthropoda had the most common infaunal associates within the four sponge species, with the hairy crab Pilumnus hirtellus being identified in all of them (Table 1). The presence of P. hirtellus in numerous sponge species was confirmed by several studies, including an investigation conducted in the Gulf of Morbihan, France on the sponge Celtodoryx girardae (Perez et al., 2006).

Annelida are almost always second or third most dominant phylum in sponges (Ribeiro et al., 2003). In Spongia officinalis, Sarcotragus spinosulus and Ircinia cf. variabilis, Annelida was the second most abundant phylum. This was also observed in two studies conducted in the North Aegean Sea using the sponges I. variabilis and S. officinalis (Koukouras et al., 1985, 1992). The Annelida also varied greatly in their frequency and abundance within the sponges, with the exception of Hediste diversicolor which obtained the highest dominance and prevalence within all sponge species. Similarly, H. diversicolor was identified as dominant in sponge communities in the Bay of Izmir, Aegean Sea (Çinar and Ergen, 2001).

Moreover, the bivalve Barbatia barbata, which was present in all sponge species except S. officinalis was also identified in Aplysina (Verongia) aerophoba, North Aegean Sea, while the other two species, Lima lima (Bivalvia) and Raphitoma contigua (Gastropoda), haven't been associated with any other sponge so far (Voultsiadou-Koukoura et al., 1987). The Ophiurida Amphiura chiajei was also present in the sponges A. aerophoba and Axinella cannabina, but there are no studies indicating the starfish Marthasterias glacialis as an endobiotic sponge associate (Koukouras et al., 1996). There is however some evidence demonstrating a feeding relationship between M. glacialis and various sponge associates, such as the bivalve Arca noae, which is a host mollusc for the sponge Crambe crambe (Marin and Belluga, 2005). It is possible that M. glacialis was lodged into the sponge by the force of the haul. Similarly, it's possible that the Spicara smaris were also accidentally lodged into I. oros during the trawl, because even though fish have been identified within sponges before, juvenile S. smaris usually inhabit soft bottoms or Posidonia meadows (Tunesi et al., 2005; Gerovasileiou et al., 2016).

The differences between the prevalence and the intensity of H. diversicolor, S. gambarelloides and C. truncata could be a consequence of several biotic and abiotic factors that affect either the sponge (host) or the associates (endobionts) directly, including environmental, biological or morphological variables (Iyaji et al., 2009; Khidr et al., 2012; Sherrard-Smith et al., 2012). An interesting case to point out is the hairy crab P. hirtellus where no matter its prevalence within sponges, it seems to have a constant intensity of about 2.7 individuals per host sponge. This could be a result of the life history of the endobiont itself. Examples of where the sponge morphology might be playing a role in the number of individuals per host sponge are the endobionts C. truncata, S. gambarelloides and H. diversicolor. This is because these species are relatively large organisms compared to the rest of the sponge associates, and in the sponge species identified they always seem to follow the same trend: highest numbers of individuals were identified within the sponge S. officinalis, followed by S. spinosulus, I. cf. variabilis and then I. oros, (Table 1).

Many of the infauna associates were common between more than one sponge species (Table 1), and all four sponges shared at least two endobiont species. Many of the endobionts were also shared with various other sponge associate communities i.e. the species, Lepidasthenia elegans (Polychaeta), Athanas nitescens (Decapoda), Colomastix pusilla (Amphipoda), C. truncata (Isopoda), Dexamine spiniventris (Amphipoda) and B. barbata (Bivalvia), were also identified in the sponge Aplysina (Verongia) aerophoba in the North Aegean Sea (Voultsiadou-Koukoura et al., 1987). A recent investigation into the endobiotic community of the sponge Sarcotragus foetidus in Greece and Cyprus, revealed common endobiotic species of Annelida (6 species), Arthropoda (5 species) and Mollusca (1 species) with the sponge samples from the current investigation (Pavloudi et al., 2016). To be more precise, it had the most mutual species from the Annelida phylum with the sponge I. cf. variabilis, from the Arthropoda with S. spinosulus, and from the Mollusca with I. oros.

Distance from the shore was the only variable that affected the total endobiotic abundance of S. spinosulus, and after further analysis the following pattern arose: at closer distances there was lower species richness with higher abundance, but as distance increased the abundance of those species decreased and species richness across all phyla increased.

Depth is a known factor influencing sponges and the abundance of endosymbionts (Ribeiro et al., 2003). In the current study depth did not significantly affect the endobiotic abundance of S. spinosulus, however, that might be because of the depth range present within our study area; no shallow zones present. Moreover, since there is no known direct association between depth and salinity, the interaction is most likely driven by a third unknown variable that could be triggered by a number of factors including currents, oxygen availability or turbidity (Bell, 2007).

The sponge volume also affected the total endobiotic community abundance. As the volume of the sponge increased and there was more available space (i.e. niche) for the organisms to use, the total endobiotic abundance increased too.

5. Conclusions

The sponge endobiotic communities identified in Cyprus seem to have similarities in their general structure with sponge associated infauna reported from other areas. Moreover, Synalpheus shrimp dominated the samples it inhabited, probably because of its bigger size and competitive advantage over other endobionts. From all four sponge species, Sarcotragus spinosulus is most likely the species that can endure the most external pressures. Depth did not significantly affect the endobiotic abundance of S. spinosulus, but that might be due to the depth range used in the study, rather than the significance of depth. Bigger sponges were able to facilitate higher community abundances, while at the same time the number of organisms increased proportionally to their relative abundance within the sponge specimens. Based on the present investigation and the arrival of the non-indigenous species (NIS) through the Suez Canal, we suggest that the endobiotic research areas that need prompt attention include the distribution and abundance of phyla within sponges, and how these interact with each other and their host. The potential effects of these NIS, which more often than not establish successfully in the Levantine Sea, a well-known hot spot of bioinvasions, need to be documented (Katsanevakis et al., 2014; Giakoumi et al., 2016; Galil et al. 2017, 2018; Rilov et al., 2017).

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Magdalene Papatheodoulou: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Carlos Jimenez: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Antonis Petrou: Performed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Ioannis Thasitis: Performed the experiments.

Funding statement

Samples were taken during the MedITS survey which was co-financed by the European Fisheries fund (2014–2020) and from national funds under tender numbers 12/2015 and 12/2016 from the Department of Fisheries and Marine Research (DFMR), Republic of Cyprus. This work was also supported by funding provided by the ProtoMedea Project 16 (MARE/2014/41 [SI2.721917]).

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the staff at AP Marine Environmental Consultancy Ltd. for their expertise, support and advice during this investigation. We are especially grateful to Maria Patsalidou for her assistance with the statistics, and Katerina Achilleos and Kyproula Chrysanthou for their help in confirming the species ID. Also, we would like to thank the R/V Megalohari captain and crew for their assistance during the survey. This paper was completed as part of a Marine and Freshwater Biology Megister thesis with title ‘Endobiotic communities of Marine Sponges in Cyprus (Levantine Sea): Role of the Host and the Environment’, by M. Papatheodoulou (2017), University of Glasgow, Scotland.

References

- Abdo D.A. Endofauna differences between two temperate marine sponges (Demospongiae; Haplosclerida; Chalinidae) from Southwest Australia. Mar. Biol. 2007;152:845–854. [Google Scholar]

- Abel E., Riedl R., Torres E. Omega; Barcelona: 1986. Fauna y flora del mar Mediterráneo: una guía sistemática para biólogos y naturalistas. [Google Scholar]

- Becerro M.A. Quantitative trends in sponge ecology research. Mar. Ecol. 2009;29:167–177. [Google Scholar]

- Bell J.J. Contrasting patterns of species and functional composition of coral reef sponge assemblages. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2007;339:73–81. [Google Scholar]

- Brown E., Colling A., Park D., Phillips J., Rothery D., Wright J. second ed. The Open University; Milton Keynes: 1995. Seawater: its Composition, Properties and Behaviour; pp. 89–97. [Google Scholar]

- Çinar M.E., Ergen Z. On the ecology of the Nereididae (Polychaeta: Annelida) in the bay of İzmir, Aegean sea. Zool. Middle East. 2001;22:113–122. [Google Scholar]

- Coll M., Piroddi C., Steenbeek J., Kaschner K., Rais Lasram F.B. The biodiversity of the Mediterranean Sea: estimates, patterns, and threats. PLoS One. 2010;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day J.H. 1967. A Monograph on the Polychaeta of Southern Africa Part 1, Errantia: Part 2, Sedentaria Published by the Trustees of the British Museum (Natural History), London. 1967 Publication no. 656. Pp. viii + 878. [Google Scholar]

- Debelius H. IKAN – Unterwasserarchiv; Germany: 1999. Crustacea Guide of the World. [Google Scholar]

- Demetropoulos A. fourth ed. Department of Fisheries; Republic of Cyprus: 1976. Echinodermata of Cyprus. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy J.E., Morrison C.L., Ríos R. Multiple origins of eusociality among sponge-dwelling shrimps (Synalpheus) Evolution. 2000;54:503–516. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2000.tb00053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Economou E., Konteatis D. Ministry of agriculture and natural resources department of fisheries; Nicosia, Cyprus: 1988. Information on the Sponge Disease of 1986 in the Waters of Cyprus. [Google Scholar]

- Economou E., Konteatis D. Ministry of agriculture and natural resources department of fisheries; Nicosia, Cyprus: 1990. Sponge Fisheries in Cyprus 1900-1989. [Google Scholar]

- EMODnet Bathymetry Consortium . 2018. EMODnet Digital Bathymetry (DTM) [Google Scholar]

- Fan L., Reynolds D., Liu M., Stark M., Kjelleberg S., Webster N.S., Thomas T. Functional equivalence and evolutionary convergence in complex communities of microbial sponge symbionts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012;109:1878–1887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203287109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauvel P. Office central de Faunistique; Paris: 2004. Faune de France – Polychetes errantes. [Google Scholar]

- Fiore C.L., Jutte P.C. Characterization of macrofaunal assemblages associated with sponges and tunicates collected off the southeastern United States. Invertebr. Biol. 2010;129:105–120. [Google Scholar]

- Galil B., Marchini A., Occhipinti-Ambrogi A., Ojaveer H. The enlargement of the Suez Canal - erythraean introductions and management challenges. Manag. Biol. Invasion. 2017;8 [Google Scholar]

- Galil B.S., Marchini A., Occhipinti-Ambrogi A. East is east and west is west? Management of marine bioinvasions in the Mediterranean Sea. Estuar. Coast Mar. Sci. 2018;201:7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Gerovasileiou V., Voultsiadou Ε. Marine caves of the Mediterranean Sea: a sponge biodiversity reservoir within a biodiversity hotspot. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerovasileiou V., Chintiroglou C.C., Konstantinou D., Voultsiadou E. Sponges as “living hotels” in Mediterranean marine caves. Sci. Mar. 2016;80:279–289. [Google Scholar]

- Giakoumi S., Guilhaumon F., Kark S., Terlizzi A., Claudet J., Felline S., Cerrano C., Coll M., Danovaro R., Fraschetti S., Koutsoubas D., Ledoux J., Mazor T., Mérigot B., Micheli F., Katsanevakis S. Space invaders; biological invasions in marine conservation planning. Divers. Distrib. 2016;22 [Google Scholar]

- de Goeij J., van Oevelen D., Vermeij M., Osinga R., Middelburg J., de Goeij A., Admiraal W. Surviving in a marine desert: the sponge loop retains resources within coral reefs. Science. 2013;342:108–110. doi: 10.1126/science.1241981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper J.N.A. SPONGUIDE. Queensland Museum, Australia. 2003. Guide to sponge collection and identification. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper J.N.A., Van Soest R.W.M. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; New York: 2002. Systema Porifera: A Guide to the Classification of Sponges. [Google Scholar]

- Iyaji F.O., Etim L., Eyo J.E. Parasite assemblages in fish hosts. Bio Res. 2009;7:561–570. [Google Scholar]

- Katsanevakis S., Coll M., Piroddi C., Steenbeek J., Ben Rais Lasram F., Zenetos A., Cardoso A.C. Invading the Mediterranean Sea: biodiversity patterns shaped by human activities. Front Mar. Sci. 2014;1 [Google Scholar]

- Kersken D., Gocke C., Brandt A., Lejzerowicz F., Schwabe E., Seefeldt M.A., Veit-Kohler G., Janussen D. The infauna of three widely distributed sponge species (Hexactinellida and Demospongiae) from the deep Ekstrom Shelf in the Weddell Sea, Antarctica. Deep-Sea res II. 2014;108:101–112. [Google Scholar]

- Khidr A.A., Said A.E., Abu Samak O.A., Abu Sheref S.E. The impacts of ecological factors on prevalence, mean intensity and seasonal changes of the monogenean gill parasite, Microcotyloides sp., infesting the Terapon puta fish inhabiting coastal region of Mediterranean Sea at Damietta region. J. Basic Appl. Zool. 2012;65:109–115. [Google Scholar]

- Klitgaard A.B. The fauna associated with outer shelf and upper slope sponges (Porifera, Demospongiae) at the Faroe Islands, northeastern Atlantic. Sarsia. 1995;80:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Koukouras A., Voultsiadou-Koukoura E., Chintiroglou H., Dounas C. Benthic bionomy of the North Aegean Sea. III. A comparison of the macrobenthic animal assemblages associated with seven sponge species. Cah. Biol. Mar. 1985;26:301–319. [Google Scholar]

- Koukouras A., Russo A., Voultsiadou-Koukoura E., Dounas C., Chintiroglou C. Relationship of sponge Macrofauna with the morphology of their hosts in the north Aegean Sea. Int. Rev. Ges. Hydrobio. Hydrogr. 1992;77:609–619. [Google Scholar]

- Koukouras A., Russo A., Voultsiadou-Koukoura E., Arvanitidis C., Stefanidou D. Macrofauna associated with sponge species of different morphology. Mar. Ecol. 1996;17:569–582. [Google Scholar]

- Manconi R., Cadeddu B., Ledda F., Pronzato R. An overview of the Mediterranean cave-dwelling horny sponges (Porifera, Demospongiae) ZooKeys. 2013;281:1–68. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.281.4171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin A., Belluga M.D.L. Sponge coating decreases predation on the bivalve Arca noae. J. Molluscan Stud. 2005;71:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Miller R., Hocevar J., Stone R., Fedorov D. Structure-forming corals and sponges and their use as fish habitat in bering sea submarine canyons. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Özcan T., Katağan T. Decapod Crustaceans associated with the sponge Sarcotragus muscarum Schmidt, 1864 (Porifera: Demospongiae) from the Levantine coasts of Turkey. Iran. J. Fish. Sci. 2011;10:286–293. [Google Scholar]

- Pansini M., Longo C. A review of the Mediterranean Sea sponge biogeography with, in appendix, a list of the demosponges hitherto recorded from this sea. Biogeographia. 2003;24:59–68. [Google Scholar]

- Pavloudi C., Christodoulou M., Mavidis M. Macrofaunal assemblages associated with the sponge Sarcotragus foetidus Schmidt. 1962 (Porifera: Demospongiae) at the coasts of Cyprus and Greece. Biodivers. Data J. 2016;4 doi: 10.3897/BDJ.4.e8210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez T., Vacelet J. The Mediterranean Sea: its History and Present Challenges. Springer; Netherlands: 2014. Effect of climatic and anthropogenic disturbances on sponge Fisheries; pp. 577–582. [Google Scholar]

- Perez T., Perrin B., Carteron S., Vacelet J., Boury-Esnault N. Celtodoryx girardae gen. nov. sp. nov., a new sponge species (Poecilosclerida: Demospongiae) invading the Gulf of Morbihan (North East Atlantic, France) Cah. Biol. Mar. 2006;47:205–214. [Google Scholar]

- Pillai T.G. Descriptions of new Serpulid polychaetes from the Kimberleys of Australia and discussion of Australian and Indo-West pacific species of Spirobranchus and superficially similar taxa. Record Aust. Mus. 2009;61:93–199. [Google Scholar]

- Pita L., Rix L., Slaby B.M., Franke A., Hentschel U. The sponge holobiont in a changing ocean: from microbes to ecosystems. Microbiome. 2018;6:1–18. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0428-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro S.M., Omena E.P., Muricy G. Macrofauna associated to Mycale microsigmatosa (Porifera, Demospongiae) in rio de Janeiro state, SE Brazil. Estuar. Coast Shelf Sci. 2003;57:951–959. [Google Scholar]

- Rilov G., Peleg O., Yeruham E., Garval T., Vichik A., Raveh O. Alien turf: overfishing, overgrazing and invader domination in south-eastern Levant reef ecosystems. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2017:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Rix L. Carbon and nitrogen cycling by Red Sea coral reef sponges. Q. J. Microsc. Sci. 2015;266:293–323. [Google Scholar]

- Ruffo S. thirteenth ed. Musée Océanographique; Mónaco: 1989. The Amphipoda of the Mediterranean. Part 1: Gammaridea (Haustoriidae to Lysianassidae). (Memoires de lnstitut oceanographique) [Google Scholar]

- Rutzler K. Sponges on coral reefs: a community shaped by competitive cooperation. Boll. Mus. Ist. Univ. Genova. 2003;68:85–148. [Google Scholar]

- San Martín G., Worsfold M.T. Guide and keys for the identification of Syllidae (Annelida, Phyllodocida) from the British Isles (reported and expected species) ZooKeys. 2015;488:1–29. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.488.9061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schejter L., Chiesa I.L., Doti B.L., Bremec C. Mycale (Aegogropila) magellanica (Porifera: Demospongiae) in the southwestern Atlantic Ocean: endobiotic fauna and new distributional information. Sci. Mar. 2012;76:753–761. [Google Scholar]

- Sherrard-Smith E., Chadwick E., Cable J. Abiotic and biotic factors associated with tick population dynamics on a mammalian host: Ixodes hexagonus infesting otters, Lutra lutra. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Soest R.W.M. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; New York: 2003. Systema Porifera: A Guide to the Classification of Sponges. [Google Scholar]

- van Soest R., Picton B., Morrow C. 1912. Marine Species Identification portal: Spongia officinalis.http://species-identification.org/species.php?species_group=sponges&id=412 [Google Scholar]

- van Soest R., Picton B., Morrow C. 1994. Marine Species Identification portal: Ircinia variabilis.http://species-identification.org/species.php?species_group=sponges&id=303&menuentry=soorten [Google Scholar]

- van Soest R., Picton B., Morrow C. 1994. Marine Species Identification portal: Sarcotragus spinosulus.http://species-identification.org/species.php?species_group=sponges&id=402&menuentry=soorten [Google Scholar]

- Spedicato-NB . 2016. International Bottom Trawl Survey in the Mediterranean Instruction Manual.http://www.sibm.it/MEDITS%202011/docs/Medits_Handbook_2016_version_8_042016.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M.W., Radax R., Steger D., Wagner M. Sponge-associated microorganisms: evolution, ecology, and Biotechnological potential. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2007;71:295–347. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00040-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tornaritis G. 1987. Mediterranean Sea Shells: Cyprus. G. Tornaritis, Cyprus. [Google Scholar]

- Trussell G., Lesser M., Patterson M., Genovese S. Depth-specific differences in growth of the reef sponge Callyspongia vaginalis: role of bottom-up effects. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2006;323:149–158. [Google Scholar]

- Tunesi L., Molinari A., Agnesi S., Di Nora T., Mo G. Presence of fish juveniles in the liguria coastal waters: synthesis of available knowledge. Biol. Mar. Mediterr. 2005;12:455–459. [Google Scholar]

- Voultsiadou E. Demosponge distribution in the eastern mediterranean: a NW-SE gradient. Helgol. Mar. Res. 2005;59:237–251. [Google Scholar]

- Voultsiadou E. Re-evaluating sponge diversity and distribution in the Mediterranean Sea. Hydrobiologia. 2009;628:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Voultsiadou-Koukoura H.E., Koukouras A., Eleftheriou A. Macrofauna associated with the sponge Verongia aerophoba in the north Aegean sea. Estuar. Coast Shelf Sci. 1987;24:265–278. [Google Scholar]

- Webster N.S., Thomas T. The sponge Hologenome. Mar. Biol. 2016;7:1–10. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00135-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]