Summary

G protein-coupled receptors are key signaling molecules and major targets for pharmaceuticals. The concept of ligand-dependent biased signaling raises the possibility of developing drugs with improved efficacy and safety profiles, yet translating this concept to native tissues remains a major challenge. Whether drug activity profiling in recombinant cell-based assays, traditionally used for drug discovery, has any relevance to physiology is unknown. Here we focused on the mu opioid receptor, the unrivalled target for pain treatment and also the key driver for the current opioid crisis. We selected a set of clinical and novel mu agonists, and profiled their activities in transfected cell assays using advanced biosensors and in native neurons from knock-in mice expressing traceable receptors endogenously. Our data identify Gi-biased agonists, including buprenorphine, and further show highly correlated drug activities in the two otherwise very distinct experimental systems, supporting in vivo translatability of biased signaling for mu opioid drugs.

Subject Areas: Biological Sciences, Physiology, Molecular Biology, Neuroscience, Bioengineering, Cell Biology

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

BRET sensors profiled MOR signaling and trafficking responses in HEK293 cells

-

•

MOR-Venus knock-in mice were created to monitor MOR trafficking in DRG neurons

-

•

MOR trafficking responses to opioids were correlated between HEK cells and neurons

-

•

Of the 10 opioid drugs tested, most remarkable were TRV130, PZM21, and buprenorphine

Biological Sciences; Physiology; Molecular Biology; Neuroscience; Bioengineering; Cell Biology

Introduction

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) play central roles in cell communication and physiology. These receptors form the largest class of proteins considered for drug discovery and are the targets for about 30% of pharmaceuticals in current use (Wacker et al., 2017). A key advance in GPCR research was the recognition that these receptors are highly dynamic proteins that adopt multiple conformations upon activation by different ligands. As a corollary, distinct agonists acting at the same receptor can engage different effector subsets, modifying cellular outcomes differently and producing distinguishable effects at system level. This concept, termed biased signaling or functional selectivity (Galandrin et al., 2007, Kenakin, 2011) forms the basis of many high-throughput screening programs to develop novel drugs with improved therapeutic potential (Wacker et al., 2017). At present, biased activities are typically established in engineered heterologous cells, overexpressing receptors and effectors, and the translation to native tissues and living organisms remains a true challenge (Zhou and Bohn, 2014). Although critical for drug development strategies, the extent to which biased signaling in recombinant cells relates to physiology remains largely unknown.

The mu opioid receptor (MOR), a GPCR family member, has emerged as a highly debated drug target as the opioid crisis intensifies in Western countries (Compton et al., 2016). This major public health crisis stems from the overprescription of opioid pain medication, leading to a sharp increase of deaths by overdoses and a devastating shift to heroin (Compton et al., 2016) and fentanyl (Suzuki and El-Haddad, 2017) abuse. However, the pain-relieving efficacy of opioids remains unmatched and, more than ever, developing opioids with low abuse potential and reduced side effects is a major goal in pain research. Among current strategies (Olson et al., 2017) toward safer opioid analgesics (Siuda et al., 2017), the design of biased MOR agonists is considered most promising. Functional selectivity at MOR, with preferential engagement of inhibitory G proteins (Gαi/o) (Gi-biased) or βarrestins (βarr-biased), is well established in heterologous cells (McPherson et al., 2010). In addition, evidence from genetic mouse mutants has suggested that limiting βarr2 recruitment at the receptor would maintain morphine analgesia but reduce adverse effects, including deadly respiratory depression (Zhou and Bohn, 2014). These promising Gαi/o-biased MOR agonists are thus developed using recombinant cell-based assays, leading notably to TRV130 (DeWire et al., 2013) undergoing clinical trials (Singla et al., 2017, Siuda et al., 2017) (and see clinicaltrials.gov), or PZM21, a novel chemotype optimized from in silico modeling and docking studies (Manglik et al., 2016). Recently, the extent of Gαi versus βarr bias for MOR ligands was proposed to correlate at the behavioral level with the analgesia or respiratory depression therapeutic window (Schmid et al., 2017). Until now, however, evidence for the direct translation of biased signaling observed in engineered cells to living neurons is lacking. In this study, we designed a novel strategy (Figure 1A) to address this key point, and our data provide the long-awaited demonstration that biased signaling properties of both traditional and newly developed MOR agonists operate similarly in native neurons.

Figure 1.

Experimental Strategy and Receptor/Effector Tools

(A) Overview of the two experimental systems (left, transfected biosensors in HEK293 cells; right, knock-in mice expressing MOR-Venus at endogenous levels in place of the native receptor), structure of the 10 MOR agonists tested in the study, assays developed for each experimental system.

(B–H) Functional characterization of MOR-Venus in HEK293 cells (B and C) and in vivo (D–H). (B) On top, schematic representation of the Gαi1/Gγ2-BRET2 biosensor assay. Upon ligand binding to the receptor, Gαi1-RlucII (d, donor) dissociates from the βγ-GFP10 (a, acceptor) dimer, which results in a decrease in BRET2 signal. Data are expressed as % of BRET signal for MOR (untagged), four replicate experiments. (C) G protein activation profile for MOR and MOR-Venus. On top, schematic representation of the pan Gγ/GRK-based BRET2 assay, Gγ3-RlucII (d, donor), and GRK2-GFP10 (a, acceptor). Upon ligand binding to the receptor, the Gα subunit dissociates from the βγ-RlucII dimer allowing recruitment of GRK2-GFP10 increasing the BRET2 signal. BRET2 was measured 10 min after stimulation with 30 μM Met-Enk. Mock shows MOR-mediated activation of endogenous G proteins. Data are expressed as percentage mock response (n = 3–5 independent experiments, one-way ANOVA). (D) There was no difference in G protein signaling in the striatum of MOR and MOR-Venus mice. [S35] GTPyS incorporation in striatal membranes prepared from MOR+/+(wild-type controls), MORVenus/+ (heterozygous knock-in), and MORVenus/Venus (homozygous knock-in) mouse littermates, in response to increasing DAMGO concentrations. Data are expressed as mean % activation ± SEM of [S35] GTPyS binding above basal (no agonist) level (3–4 independent experiments with duplicates). Two-way ANOVA found no difference of drug effects across genotypes. (E) MOR+/+ and MORVenus/Venus injected with morphine (40 mg/kg i. p.) or saline show similar locomotor responses (10-min bins). Data are expressed as the distance traveled in centimeters (n = 5–6/group, two-way ANOVA, significant drug effect, no genotype effect). (F) Morphine analgesia is intact in MOR and MOR-Venus mice. Animals were injected with morphine (5 or 10 mg/kg intraperitoneally) or saline. Left, analgesia in the hot plate test, measured by latency to lick the hind paw (n = 3–4/group, two-way ANOVA, significant drug effect at 10 mg/kg, no genotype effect). Right, analgesia in the tail immersion test (52°C), measured by tail withdrawal latency (n = 3–4/group, two-way ANOVA, significant drug effect at 5 and 10 mg/kg, no genotype effect). Cutoff to be removed from the test (10 s) is indicated by a broken line. (G) Whole-brain mapping of MOR-Venus expression (quantification in Table S1). The scheme shows an overview of MOR-Venus distribution in soma (blue), fibers (green), or both (gold) across brain areas enriched for the receptor. MH, medial habenula; fr, fasiculus retroflexus; IPN, interpeduncular nucleus; CP, caudate putamen; PVT, paraventricular thalamus; PB, parabrachial nucleus. (H) Sections of MOR-Venus dorsal root ganglia (DRG) detect MOR either directly (intrinsic, Venus fluorescence) or using Venus amplification (anti-Venus antibody, amplified). All data in (B–F) are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance is defined as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Results

Designing the MOR-Venus Tool in Recombinant Cells

We first designed a customized version of MOR amenable to distinguish agonist activities in a physiological context. As agonist-induced MOR trafficking is considered a hallmark of biased signaling (Williams et al., 2013), and is a measurable endpoint in vivo, we created an MOR version that would be traceable in tissues. Guided by our previous work (Erbs et al., 2015), we fused the mouse MOR to Venus-YFP (MOR-Venus) the most versatile fluorophore compatible with resonance energy transfer (RET) biosensors (Breton et al., 2010) and best detectable in living cells (Nagai et al., 2002). We tested the integrity of MOR-Venus signaling in HEK293 cells, typically used for drug screening and signaling assays. In a Gαi/Gγ-dissociation bioluminescence RET2 (BRET) biosensor assay (Gales et al., 2006), the reference MOR endogenous opioid Met-enkephalin (Met-Enk) stimulated Gαi1 with similar potency and efficacy in recombinant MOR (untagged) and MOR-Venus (tagged) receptors (Figure 1B). In a pan G protein Gγ/GPCR kinases (GRKs) recruitment-based BRET2 assay (Karamitri et al., 2018), absolute values for basal G protein signaling were comparable between untagged and tagged receptors (Figure S1A). Furthermore, Met-Enk promoted activation of all Gαi and Gαo family members, but was inactive at Gαq for both MOR and MOR-Venus (Figure 1C). Also, similar preference toward GαoA, GαoB, Gαi2, and Gαi3 was found for the two receptors. Finally, we created a human version of MOR-Venus, and tested both mouse and human receptors for the activation of 7 mouse and 14 human Gα subunits, using the Gγ/GRK-based BRET2assay (Figures S1B–S1E). This comprehensive profiling showed no difference in Met-Enk responses, whether the receptor was mouse or human or tagged or untagged, or whether Gα was mouse or human. Altogether, these data suggest that the Venus fusion does not alter receptor signaling and supports data translatability between mouse and human MOR signaling.

Creating the MOR-Venus Mouse to Tackle Physiological Signaling

We then created the corresponding MOR-Venus knock-in mouse line by homologous recombination, so that MOR-Venus is expressed in place of the native receptor (Figure S2A). MOR mRNA levels in brain samples from Oprm1Venus/Venus homozygous (MOR-Venus mice), Oprm1Venus/+ heterozygous, and Oprm1+/+control littermates were comparable (Figure S2B), and [D-Ala2, N-MePhe4, Gly-ol]-enkephalin (DAMGO)-induced G protein activation in striatal membranes showed superimposable dose-responses for all three genotypes (Figure 1D). Morphine-induced locomotor stimulation (Figure 1E) and analgesia (Figure 1F) were also intact in MOR-Venus mice, indicating altogether that the MOR-Venus receptor is expressed at levels comparable to endogenous receptors in the animal and is fully functional. MOR-Venus distribution analysis showed co-localized expression of both tagged and untagged receptors in heterozygous animals (Figure S3). Mapping throughout the nervous system revealed an MOR-Venus expression pattern consistent with previous reports (Figures S4A–S4C, Table S1, and see Erbs et al., 2015) and provided additional details on MOR localization in soma or fibers (Figure 1G). Finally, MOR-Venus expression in sensory neurons of dorsal root ganglia (DRGs, see Figure 1H) matched the known predominant MOR expression in first-order nociceptive neurons (Scherrer et al., 2009). MOR-Venus mice, therefore, provide an ideal physiological assay system to profile MOR agonist activities, under conditions that recapitulate native receptor expression.

Profiling Drug Activities for 10 Mu Opioid Agonists in Recombinant Cells

Next, we measured the activities of selected opioid agonists at MOR-Venus, in the HEK293 cell heterologous system. The 10 selected compounds included prescribed or abused MOR agonists (morphine, oxycodone, buprenorphine, fentanyl), prototypic peptidic compounds (Met-Enk, DAMGO, endomorphin-1), and Gαi/o-biased agonists from recent drug discovery efforts (TRV130, PZM21) (Figure 1A).

In HEK293 cells, concentration-response curves for Gαi2 activation using Gαi/Gγ-BRET2 showed highly similar curves for all the drugs, except for oxycodone, which had a trend of lower potency and for buprenorphine, which had significantly lower efficacy and potency than Met-Enk (Figure 2A and Table S2). Testing all three Gαi subunits in the Gαi/Gγ-BRET2 biosensor assay revealed no significant difference in basal activity for MOR-Venus and untagged MOR (Figures S5A and S5B), and highly similar drug responses for Gαi1 and Gαi3 (Figures S5C and S5D).

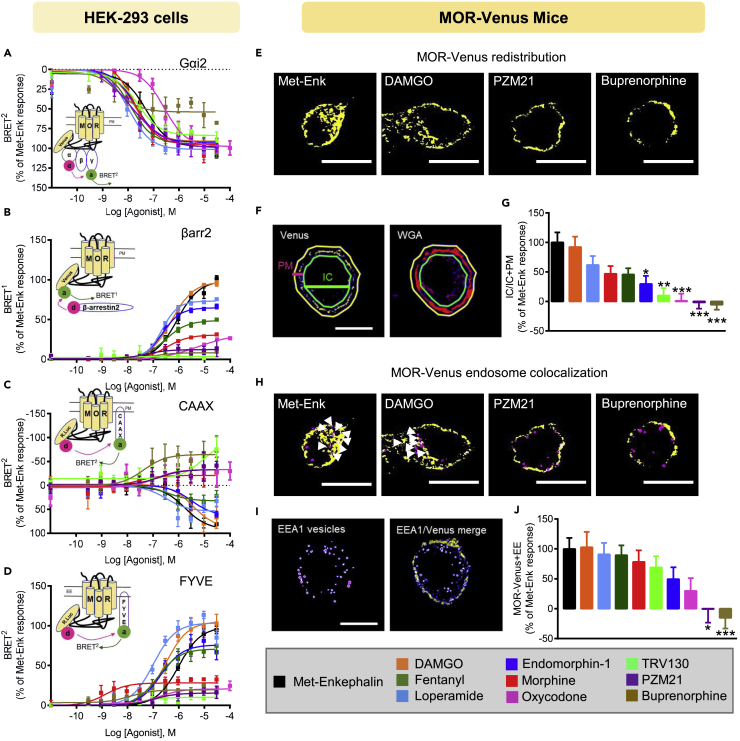

Figure 2.

Profiling MOR Agonists in the Two Experimental Systems

(A–J) Data obtained from HEK293 cells overexpressing MOR-Venus (A–D) and DRG neurons from MOR-Venus mice (E–J). (A) Gαi2 responses in HEK293 cells. On top, schematic representation of the Gαi2/Gγ2-BRET2 biosensor assay with BRET2 sensors (Gαi2-RlucII, d, donor; Gγ2-GFP10, a, acceptor). Cells were stimulated 10 min with increasing concentrations of the indicated compound. Data are expressed as % of Met-Enk response n = 3–7 independent experiments. (B) βarr2 recruitment in HEK293 cells. On top, schematic representation of the MOR/βarr2 BRET1 biosensor assay. Upon activation, RlucII-tagged βarr2 (d, donor) is recruited to MOR-Venus (a, acceptor), resulting in increased BRET1signal. Cells were stimulated 10 min with increasing concentrations of the indicated compound. Data are expressed as mean % of the maximal response induced by Met-Enk (n = 4–9 independent experiments). (C) Receptor internalization in HEK293 cells. On top, schematic representation of the MOR/CAAX BRET2 biosensor assay, used to monitor receptor disappearance from the plasma membrane (PM). MOR-RlucII is the donor (d), and rGFP-tagged CAAX is the acceptor (a). HEK293 cells were exposed to increasing concentrations of MOR agonists for 30 min. Data are expressed as % of Met-Enk response (4–7 independent experiments). (D) Receptor translocation to endosomes in HEK293 cells. On top, schematic representation of MOR/FYVE BRET2 biosensor assay, used to monitor receptor translocation to early endosomes (EE). MOR-RlucII is the donor (d), and rGFP-tagged FYVE is the acceptor (a). HEK293 cells were exposed to increasing concentrations of MOR agonists for 30 min. Data are expressed as mean % of the maximal response induced by Met-Enk (n = 4–7 independent experiments). (E–G) Receptor redistribution in DRG neurons. (E) DRG neurons from adult MOR-Venus mice were dissociated and exposed to 1 μM MOR agonist for 10 min. Representative confocal images are shown after thresholding (see Transparent Methods) and reveal MOR-Venus redistribution to intracellular compartments for Met-Enk and DAMGO (left panel) but not PZM21 and buprenorphine (two right panels). Scale bar, 10 μm. (F) Quantification method. A vehicle-treated neuron illustrates the method used to quantify MOR-Venus redistribution in neurons (anti-Venus antibody; left, yellow, plasma membrane (PM) label; WGA-Alexa594, right, red). PM and intracellular (IC) compartments were defined by drawing regions of interest (PM, yellow outer line; IC, green inner line). Fluorescence intensity was measured in the two compartments, quantified as IC/total (IC + PM), and vehicle was subtracted. (G) MOR-Venus redistribution following treatment with the 10 MOR compounds. Data are expressed as %IC/IC + PM of the Met-Enk response (n = 26–52 cells per drug condition). (H–J) Receptor co-localization to early endosomes (EEs) in DRG neurons. (H) Representative confocal images show MOR-Venus DRG neurons exposed to 1 μM MOR agonist for 10 min and immunostained to amplify MOR-Venus (anti-Venus antibody, yellow) and label EEs (anti-EEA1 antibody, magenta). Met-Enk and DAMGO (left panel), but not PZM21 and buprenorphine (2 right panels), increases MOR-Venus/EE co-localization. Scale bar, 10 μm; white arrowheads locate double-positive MOR-Venus/EEA1 vesicles. (I) Quantification method. A vehicle-treated cell illustrates the method of quantification in the EE assay. Confocal images were thresholded (see Transparent Methods), and individual vesicles were outlined as ROI using the EEA1 channel. ROI were then counted in either EEA1 or Venus channels to determine the number of EEA1 vesicles containing MOR-Venus. (J) MOR-Venus co-localization with EEs following treatment with the 10 MOR compounds. Data are expressed as % of Met-Enk response (n = 26–42 cells per drug condition). All data in (A–D), (G), and (J) are shown as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance of the differences (G and J, one-way ANOVA) is defined as *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 versus Met-Enk condition.

To test βarr2 recruitment, we used the Venus fusion of MOR as the BRET1 acceptor for βarrestin-RlucII (Figure 2B) and obtained robust BRET responses, indicating that MOR-Venus itself may be used as a biosensor. We obtained a wide range of responses for the 10 drugs, suggesting that βarr2 engagement is a better differentiating factor than the Gαi response. Co-expressing GRKs 2, 5, or 6 increased βarr2 recruitment for most drugs (Figure S6B) as expected (Ribas et al., 2007, Williams et al., 2013), although notably the effect was modest for TRV130, PZM-21, and buprenorphine (Tables S3A and S3B). Of note, the Venus tag did not modify basal βarr2 recruitment, as there was no significant difference between MOR-Venus and untagged MOR in a control experiment measuring basal βarr2 recruitment (Figure S6A).

We next used our recently developed enhanced bystander (ebBRET) biosensors (Figures S7A and S7D) to monitor receptor redistribution upon agonist exposure (Namkung et al., 2016), an event tightly linked to βarr2 engagement. In receptor-independent control experiments, we found that untagged MOR and MOR-Venus showed no statistical difference in their activities to translocate βarr2 to endosomes, either in the absence of agonist (Figure S7B) or in the presence of Met-Enk (Figure S7C). As the MOR tag had no apparent effect in this assay, we next compared the 10 selected compounds using MOR-RlucII as the donor to directly monitor receptor redistribution upon agonist exposure (Figure S7D). As expected, Met-Enk promoted receptor disappeared from the plasma membrane (PM), detected using the rGFP-CAAX biosensor, and the receptor concomitantly accumulated in early endosomes (EE), detected using rGFP-FYVE (Figures S7D and S7E). As for βarr2 profiling, testing the 10 drugs showed a wide range of activities in both CAAX (Figure 2C) and FYVE (Figure 2D) assays. The observation that buprenorphine, and to a lesser extent oxycodone and morphine, increased the CAAX BRET signal (Table S4) suggests that these drugs may, in fact, inhibit constitutive endocytosis or recruit more receptors to the PM. In the FYVE assay, agonists induced receptor translocation to endosomes to a similar extent for all compounds except morphine, oxycodone, PZM21, TRV130, and buprenorphine, which had significantly lower efficacies when compared with Met-Enk (Figure 2D and Table S5). Overexpression of GRK2 alone or in the presence of βarr2 (Figures S7F and S7G) enhanced both the loss of receptor from the PM (CAAX) and their translocation to EE (FYVE) for most drugs (Tables S4 and S5). Exceptions were PZM21, TRV130, and buprenorphine with significantly lower efficacies in the CAAX assay when compared with Met-Enk in the presence of GRK2 and βarr2 (Figure S7F and Table S4), and, remarkably, buprenorphine maintained a significantly lower efficacy in the trafficking assay (Figure S7G and Table S5), whereas TRV130 and PZM21 responded to a similar efficacy as Met-Enk.

Profiling Drug Activities for 10 Mu Opioid Agonists in Native Neurons

We then tested the activities of the 10 drugs on DRG neurons, which we extracted from adult MOR-Venus mice. These cells are most relevant to pain control and well suited for quantification by confocal imaging (Figure S8A). PM was labeled using WGA-AlexaFluor594, and fluorescence in intracellular (IC) compartment versus PM was compared (Figure 2F thereafter called IC assay). DAMGO dose- and time-dependently increased the translocation of MOR-Venus signal intracellularly (Figure S8B), indicating the sub-maximal dose as 1 μM and 10-min time point for the best assay conditions to compare the 10 drugs for their ability to promote endocytosis in neurons. MOR-Venus DRG neurons were then exposed to each drug and imaged (Figures 2E–2G, S9A, and S9B). A range of effects was obtained, from compounds producing MOR-Venus redistribution similar to Met-Enk-induced responses (DAMGO) to those that significantly differed either only weakly redistributing (TRV130, oxycodone), or even increasing MOR-Venus at the PM (PZM21 and buprenorphine) (Figures 2G and S9A and Table S6). Furthermore, agonist-induced receptor redistribution was not modified by the level of MOR-Venus expression, as high- and low-MOR-Venus-expressing neurons showed similar responses (Figure S10A) and Pearson correlation between IC assay and total MOR-Venus signals was not significantly correlated (r = 0.3069, p = 0.3883) for the selected 10 compounds (Figure S10B).

We designed another assay to measure MOR-Venus co-localization to EEs (Figures 2H–2J and S11A–S11C) by overlaying EEA1-positive vesicles in DRG neurons with MOR-Venus fluorescence, and counting for double-positive signals. Overall, drug treatment did not significantly modify the average number of EEA1-labeled vesicles per cell when compared with Met-Enk (Figure S11C) but increased the percentage of vesicles showing EEA1 and MOR-Venus co-localization (Figure 2J). Again, drug effects were compared to Met-Enk responses (Table S7) and ranged from similar (DAMGO) receptor to endosome translocation to none (PZM21), or even opposing (buprenorphine) effect (Figure 2J), consistent with the data obtained with the IC assay.

Establishing Drug Signatures

Altogether the 10 drugs showed a wide range of activities. We next further estimated drug signaling efficacy using the operational model integrating logarithms of the transduction coefficient (Δlog(τ/Ka)) derived from concentration-response curves (Black and Leff, 1983) obtained in HEK293 cells (see Methods and Figure 3, upper radial plots). These transduction coefficients were further used to estimate the bias between either Gαi2 and βarr2 or MOR localization to EE compartments (FYVE assay) (Table S8). Notably, this analysis found morphine, oxycodone, TRV130, PZM21, and buprenorphine to be Gαi2-biased for both estimates of bias. Fentanyl showed bias toward Gαi2 over βarr2 in the absence of additional GRK2; however, when GRK2 was added, βarr2 recruitment (Table S3B) was increased to a similar efficacy level as Met-Enk response suggesting that this Gαi2 bias may be dependent on GRK2 availability.

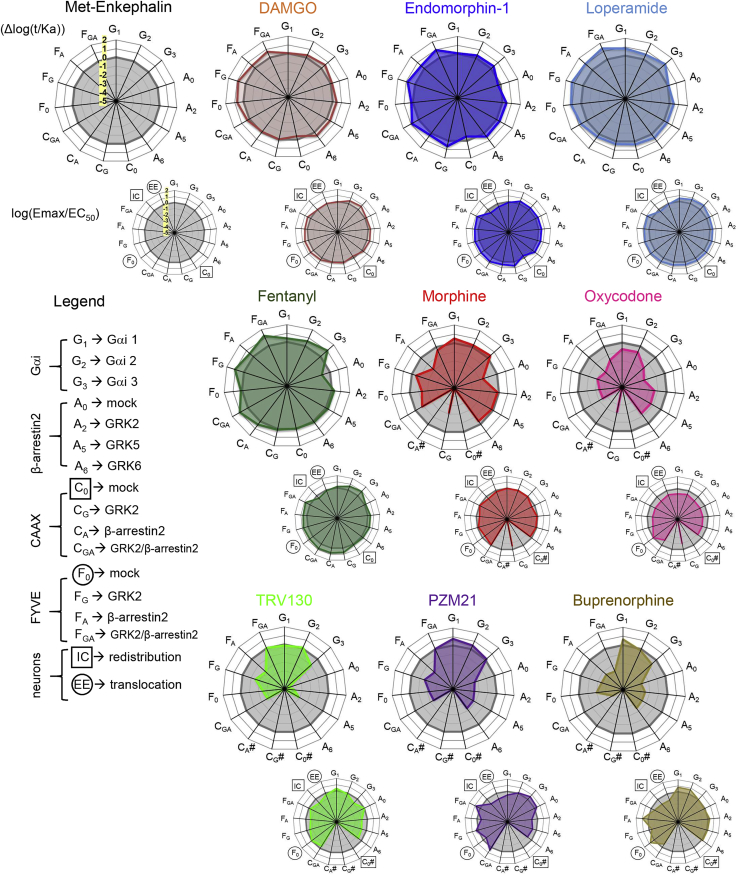

Figure 3.

Buprenorphine Stands Out among 10 Signatures of MOR Agonists

Radial graphs illustrating the specific activity signature (see Transparent Methods) for each drug (colored line) compared with Met-Enk (gray line). Upper radial plots: dose-response curves for the HEK293 cell data were used to derive the logarithm of the “transduction coefficients” (Δlog(τ/Ka)) to integrate efficacy (τ) and affinity (Ka). Lower radial plots integrate single concentration effect in neurons and dose-response effects in HEK293 cell data as follows: dose-response curves were used to fit HEK293 cell data into an Emax/EC50 ratio to estimate signaling efficacy, whereas the neuronal (DRG) data (Figure 2G or 2J), where all drug treatments were done at submaximal dose (Figure S8B), were normalized as ((compound/Met-Enkephalin)-Met-Enkephalin), thus Met-Enkephalin response is set to 0. For both HEK293 cells and native neurons positive and negative values denote a better or a lower response when compared with Met-Enkephalin. Top left, the scale is highlighted in yellow on the reference Met-Enk radial plot (min −5 to max 2 with intervals of 1). The legend indicates the assay abbreviations. # Indicates a drug effect that was too low or could not be fitted to the operational model.

To better illustrate the data, we integrated the overall efficiency of the drugs using the Emax/EC50 ratios in HEK293 cells with the 1 μM drug responses in native neurons for each drug in radial graphs (see Methods and Figure 3, lower radial plots), providing a set of MOR agonist signatures. Note that only the HEK293 cell data were derived from concentration-effect values. Agonist profiles formed a continuum, but can essentially be discussed as three groups. DAMGO, endomorphin-1, loperamide, and fentanyl were close to the reference Met-Enk, showing both efficient Gαi and βarr2 activities in HEK293 cells, consistent with previous studies (Pradhan et al., 2012). Moreover, the four drugs also showed comparable trafficking effects in HEK293 cells (enhanced by GRK2/βarr2 overexpression) and DRG neurons. The second and third groups had in common lower effects in the CAAX assay that made them unable to be fitted to the operational model. In the second group, morphine and oxycodone shared a similar Gαi-biased profile, although oxycodone was less active overall. Morphine in HEK293 cells showed efficient Gαi signaling, whereas βarr2 engagement was marginally observed unless GRKs were overexpressed. Morphine was also able to induce receptor redistribution in HEK293 cells (FYVE and CAAX with GRK2/βarr2 overexpression) as well as under physiological conditions (both IC and EE assays). The third group includes TRV130, PZM21, and buprenorphine; all were Gαi2 biased, but only buprenorphine showed insensitivity to GRK2/βarr2 overexpression in the CAAX and FYVE assays in HEK293 cells. In neurons, subtle differences further distinguished the three compounds. TRV130 moderately increased endosomal co-localization (Figure 2J), whereas PZM21 and buprenorphine did not, possibly due to MOR-Venus externalization (Zaki et al., 2000) and/or stabilization at the PM. Finally, although Gαi-biased profiles were anticipated for TRV130 (Siuda et al., 2017) and PZM21 (Manglik et al., 2016), the extreme position of buprenorphine in our neuron-based assays was striking. Similar to the trafficking responses in the neurons, buprenorphine showed the lowest efficacy in HEK293 trafficking assays despite addition of GRK2/βarr2 (Tables S4 and S5) displaying a signaling signature presumably optimal for a better therapeutic safety window (Schmid et al., 2017). This long-standing prescribed drug for opioid addiction treatment (Ayanga et al., 2016), in fact, has been neglected for pain treatment and may be reconsidered (Ehrlich and Darcq, 2019, Khanna and Pillarisetti, 2015).

Correlating Trafficking Activities in Recombinant Cells and DRG Neurons

Finally, we compared activities of the compounds in the two experimental systems, to directly assess the translatability of HEK293 cell responses to neurons. As IC redistribution and EEA1 colocalization in DRG neurons are best comparable with CAAX and FYVE biosensor responses in HEK293 cells, respectively, we used Emax from HEK293 cell dose-response curves (Figures 2C and 2D and Tables S4 and S5) and the submaximal-dose-derived percentage Met-Enk neuronal responses (Figures 2G and 2J) for correlation analysis. We found strong positive correlation for both dataset comparisons (Figure 4A, r = 0.8784 and ***p = 0.0008;Figure 4B, r = 0.9141 and ***p = 0.0002). This result demonstrates that biased signaling of MOR agonists, typically established in traditional drug screening systems, is physiologically relevant to neurons.

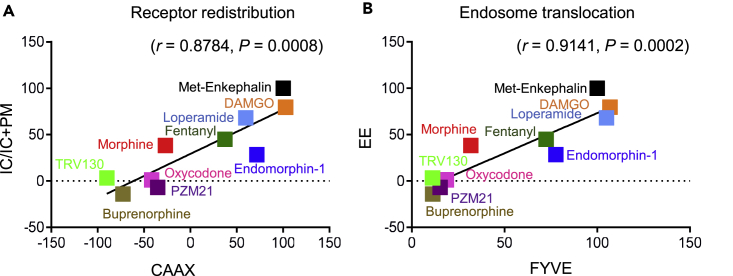

Figure 4.

MOR Trafficking Is a Suitable Readout for Ligand-Dependent Activities

Pearson correlation analysis was used to examine the compatibility of trafficking responses for the 10 MOR compounds in two distinct systems. The best comparable assays between transfected MOR-Venus and native MOR-Venus systems were CAAX or FYVE biosensors in HEK293 cells with receptor redistribution to intracellular (IC) or early endosome (EE) compartment assays in DRG neurons. Dose-response curves (Figures 2C and 2D) were used to derive Emax values in % of Met-Enkephalin (Met-Enk) from HEK293 cells, and sub-maximal dose neuronal data in % of Met-Enk (Figures 2G and 2J) were used for correlation.

(A) Positive correlation between receptor redistribution in DRG neurons (IC + IC/PM) and HEK293 cell (MOR-Rluc/rGFP-CAAX) assays (Pearson correlation: r = 0.8784, p = 0.0008).

(B) Between-receptor co-localization with EEs in DRG neurons (EE) and HEK293 cell (MOR-Rluc/FYVE-rGFP) assays (Pearson correlation: r = 0.9141, p = 0.0002).

Discussion

GPCRs constitute the largest family of protein targets for approved drugs in the United States and European Union (Sriram and Insel, 2018), and emerging strategies to design new GPCR-based therapeutics take advantage of biased signaling to improve efficacy and safety (Ehrlich et al., 2019, Hauser et al., 2017). At present, drug signaling profiles are established using overexpressed receptors and effectors in non-neuronal cells, which are practical for biosensor-based assays, but the translation to endogenous receptors in living neurons remains a major question as receptor density is lower by several orders of magnitude and effector availability is essentially unknown (Luttrell et al., 2018). Here we used the MOR as a model receptor to approach this question. The alarming context of the current opioid epidemic has led to developing novel Gαi/o-biased MOR agonists (TRV130 and PZM21) to limit adverse opioid effects (DeWire et al., 2013, Manglik et al., 2016, Schmid et al., 2017), which we studied here together with clinically used and abused opiates.

Earlier studies that have examined a large set of MOR agonists' ability to activate G proteins, phosphorylate MOR, recruit βarr2, and internalize the receptor (McPherson et al., 2010) have primarily been performed in transfected HEK293 cells. Here we developed a knock-in mouse line, which produces a detectable version of the receptor (MOR-Venus) in place of the native receptor. In HEK293 cells, basal G protein activation profile, βarr2 recruitment, and trafficking to endosomes were comparable for untagged and MOR-Venus-tagged receptors. In the mouse, MOR-Venus mediated behavioral morphine effects (hyperlocomotion and analgesia) similar to the native receptor. MOR-Venus is therefore fully functional in both overexpression HEK293 cell-based assays and in the mouse, providing an ideal tool to compare drug-induced trafficking under artificial and physiological conditions. We found that, the Gαi/o-biased TRV130, PZM21, and buprenorphine induced virtually no receptor redistribution or endosome translocation, whereas clinical and peptidic ligands showed limited to strong trafficking effects, and, importantly, these activities were remarkably correlated in recombinant and physiological assays. Our study therefore provides a long-awaited validation of early-stage preclinical efforts for MOR drug discovery and also holds promise for GPCR drug discovery in general.

Trafficking analyses provided the best differentiation of drug effects in HEK293 cells, and receptor redistribution at subcellular level may represent a further research path to characterize drug activities. Future analysis of MOR-Venus trafficking in distinct cellular compartments may further differentiate drug activities in native neurons and provide novel and perhaps translatable insights into agonist-dependent MOR signaling in vivo (Irannejad et al., 2017). Recently, location-specific MOR activation was monitored using a genetically encoded conformational biosensor, and revealed ligand-dependent signaling at the subcellular level, with opioid alkaloid effects detected at the level of Golgi in both soma and dendrites, whereas opioid peptide signaling remaining confined to the PM and EE (Stoeber et al., 2018). Moving forward, these studies and ours reveal novel facets of drug activities by directly observing receptor redistribution intracellularly, which will further refine drug activity profiles. MOR-Venus mice, which were developed for optimal RET, will be a unique tool to develop next-generation biosensors and characterize biased opioid signaling and trafficking in vivo.

Buprenorphine (Subutex), which was long used as a treatment for opioid addiction, appears to be a remarkable drug in both overexpression and native systems of this study. In transfected cells, the overexpression of GRK2 and βarr2, known to enhance agonist-induced trafficking, increased responses for all the compounds, including TRV130 and PZM21, but buprenorphine remained largely insensitive. In native neurons, buprenorphine showed the most significant PM-receptor retaining activity in both redistribution and endosome localization assays. The buprenorphine signature, therefore, is closer to recently developed Gi-biased drugs (TRV 130 and PZM21) than any other drug tested in this study. This observation suggests that this clinically safe and efficient analgesic is worth revisiting for pain management as an alternative to common clinical opioids (fentanyl and morphine) (Ehrlich and Darcq, 2019).

To conclude, moving from neuronal cells to whole-organism responses will address yet another level of complexity, and how findings from this study translate to whole animals remains to be seen. Recent improvements in whole animal imaging, for second messengers (Ca2+ miniscopes, cAMP in vivo biosensors) will be instrumental to fully profile drug signaling in vivo (Girven and Sparta, 2017, Kerr and Nimmerjahn, 2012), and ultimately relate circuit-level understanding of biased signaling (Urs et al., 2016) to the amazingly distinct properties of traditional and innovative MOR agonists at the behavioral level (Schmid et al., 2017).

Limitations of the Study

The resolution of MOR-positive DRG neurons was limited in the present study to neurons detected in our primary culture conditions. Future studies, on intact DRG slices or intravital whole animal imaging should improve the characterization of MOR ligands across all DRG neuronal subtypes and elucidate key actions of these MOR neuronal subsets in pain.

Methods

All methods can be found in the accompanying Transparent Methods supplemental file.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Consortium Québécois de Découverte de Médicaments and the Region Alsace/Biovalley (M.B. and B.L.K.) and Fonds Européen de Développement Régional (B.L.K.). We thank NIDA Drug Supply Program and Alkermes for providing the drugs. We also thank the Mouse Clinic Institute (Illkirch, France) for generating MOR-Venus mice. We thank Aude Villemain, Karine Lachapelle, and DaWoon Park as well as the staff at the Douglas Neurophenotyping Animal Facility for animal care. We thank the Molecular and Cellular Microscopy Platform of the Douglas Mental Health University Institute for microscope usage. We also thank Monique Lagacé for assistance editing the manuscript. This work was also supported by National Institute of Health (National Institute of Drug Abuse Grant No. 05010 to B.L.K.), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Grants # MOP11215 and FDN148431 to M.B.), and the Canada Foundation for Innovation. B.L.K. holds the Canada Research Chair in Neurobiology of Addiction and Mood Disorders. M.B. holds the Canada Research Chair in Signal Transduction and Molecular Pharmacology.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.T.E., M.B., and B.L.K.; Methodology, A.T.E., M.S., E.D., M.B., and B.L.K.; Formal Analysis, A.T.E., M.S., D.F.D.F., L.R., and F.G.; Investigation, A.T.E., M.S., F.G., D.F.D.F., L.R., C.C., and A.M.; Resources, C.L.G., M.H., and V.L.; Writing – Original Draft, A.T.E. and M.S.; Writing – Reviewing & Editing, A.T.E., M.S., B.L.K., and M.B.; Supervision, M.B. and B.L.K.; Funding Acquisition, M.B. and B.L.K.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest. Some of the BRET-based biosensors used in this study are the object of patent protection and were licenced to Domain Therapeutics; all BRET-based biosensors can be obtained for non-commercial use through regular academic material transfer agreements.

Published: April 26, 2019

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2019.03.011.

Contributor Information

Michel Bouvier, Email: michel.bouvier@umontreal.ca.

Brigitte L. Kieffer, Email: brigitte.kieffer@douglas.mcgill.ca.

Supplemental Information

References

- Ayanga D., Shorter D., Kosten T.R. Update on pharmacotherapy for treatment of opioid use disorder. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2016;17:2307–2318. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2016.1244529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black J.W., Leff P. Operational models of pharmacological agonism. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1983;220:141–162. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1983.0093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breton B., Lagace M., Bouvier M. Combining resonance energy transfer methods reveals a complex between the alpha2A-adrenergic receptor, Galphai1beta1gamma2, and GRK2. FASEB J. 2010;24:4733–4743. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-164061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton W.M., Jones C.M., Baldwin G.T. Relationship between nonmedical prescription-opioid use and heroin use. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016;374:154–163. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1508490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWire S.M., Yamashita D.S., Rominger D.H., Liu G., Cowan C.L., Graczyk T.M., Chen X.T., Pitis P.M., Gotchev D., Yuan C. A G protein-biased ligand at the mu-opioid receptor is potently analgesic with reduced gastrointestinal and respiratory dysfunction compared with morphine. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2013;344:708–717. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.201616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich A.T., Darcq E. Recommending buprenorphine for pain management. Pain Manag. 2019;9:13–16. doi: 10.2217/pmt-2018-0069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich A.T., Kieffer B.L., Darcq E. Current strategies toward safer mu opioid receptor drugs for pain management. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets. 2019 doi: 10.1080/14728222.2019.1586882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erbs E., Faget L., Scherrer G., Matifas A., Filliol D., Vonesch J.L., Koch M., Kessler P., Hentsch D., Birling M.C. A mu-delta opioid receptor brain atlas reveals neuronal co-occurrence in subcortical networks. Brain Struct. Funct. 2015;220:677–702. doi: 10.1007/s00429-014-0717-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galandrin S., Oligny-Longpre G., Bouvier M. The evasive nature of drug efficacy: implications for drug discovery. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2007;28:423–430. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gales C., Van Durm J.J., Schaak S., Pontier S., Percherancier Y., Audet M., Paris H., Bouvier M. Probing the activation-promoted structural rearrangements in preassembled receptor-G protein complexes. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2006;13:778–786. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girven K.S., Sparta D.R. Probing deep brain circuitry: new advances in in vivo calcium measurement strategies. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2017;8:243–251. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.6b00307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser A.S., Attwood M.M., Rask-Andersen M., Schioth H.B., Gloriam D.E. Trends in GPCR drug discovery: new agents, targets and indications. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2017;16:829–842. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irannejad R., Pessino V., Mika D., Huang B., Wedegaertner P.B., Conti M., von Zastrow M. Functional selectivity of GPCR-directed drug action through location bias. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017;13:799–806. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karamitri A., Plouffe B., Bonnefond A., Chen M., Gallion J., Guillaume J.-L., Hegron A., Boissel M., Canouil M., Langenberg C. Type 2 diabetes-associated variants of the MT2 melatonin receptor affect distinct modes of signaling. Sci. Signal. 2018 doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aan6622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenakin T. Functional selectivity and biased receptor signaling. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2011;336:296–302. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.173948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr J.N., Nimmerjahn A. Functional imaging in freely moving animals. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2012;22:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna I.K., Pillarisetti S. Buprenorphine - an attractive opioid with underutilized potential in treatment of chronic pain. J. Pain Res. 2015;8:859–870. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S85951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luttrell L.M., Maudsley S., Gesty-Palmer D. Translating in vitro ligand bias into in vivo efficacy. Cell Signal. 2018;41:46–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2017.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manglik A., Lin H., Aryal D.K., McCorvy J.D., Dengler D., Corder G., Levit A., Kling R.C., Bernat V., Hubner H. Structure-based discovery of opioid analgesics with reduced side effects. Nature. 2016;537:185–190. doi: 10.1038/nature19112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson J., Rivero G., Baptist M., Llorente J., Al-Sabah S., Krasel C., Dewey W.L., Bailey C.P., Rosethorne E.M., Charlton S.J. mu-opioid receptors: correlation of agonist efficacy for signalling with ability to activate internalization. Mol. Pharmacol. 2010;78:756–766. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.066613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai T., Ibata K., Park E.S., Kubota M., Mikoshiba K., Miyawaki A. A variant of yellow fluorescent protein with fast and efficient maturation for cell-biological applications. Nat. Biotechnol. 2002;20:87–90. doi: 10.1038/nbt0102-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namkung Y., Le Gouill C., Lukashova V., Kobayashi H., Hogue M., Khoury E., Song M., Bouvier M., Laporte S.A. Monitoring G protein-coupled receptor and beta-arrestin trafficking in live cells using enhanced bystander BRET. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:12178. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson K.M., Lei W., Keresztes A., LaVigne J., Streicher J.M. Novel molecular strategies and targets for opioid drug discovery for the treatment of chronic pain. Yale J. Biol. Med. 2017;90:97–110. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan A.A., Smith M.L., Kieffer B.L., Evans C.J. Ligand-directed signalling within the opioid receptor family. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2012;167:960–969. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02075.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribas C., Penela P., Murga C., Salcedo A., Garcia-Hoz C., Jurado-Pueyo M., Aymerich I., Mayor F., Jr. The G protein-coupled receptor kinase (GRK) interactome: role of GRKs in GPCR regulation and signaling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2007;1768:913–922. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherrer G., Imamachi N., Cao Y.Q., Contet C., Mennicken F., O'Donnell D., Kieffer B.L., Basbaum A.I. Dissociation of the opioid receptor mechanisms that control mechanical and heat pain. Cell. 2009;137:1148–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid C.L., Kennedy N.M., Ross N.C., Lovell K.M., Yue Z., Morgenweck J., Cameron M.D., Bannister T.D., Bohn L.M. Bias factor and therapeutic window correlate to predict safer opioid analgesics. Cell. 2017;171:1165–1175.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.10.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singla N., Minkowitz H.S., Soergel D.G., Burt D.A., Subach R.A., Salamea M.Y., Fossler M.J., Skobieranda F. A randomized, Phase IIb study investigating oliceridine (TRV130), a novel micro-receptor G-protein pathway selective (mu-GPS) modulator, for the management of moderate to severe acute pain following abdominoplasty. J. Pain Res. 2017;10:2413–2424. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S137952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siuda E.R., Carr R., 3rd, Rominger D.H., Violin J.D. Biased mu-opioid receptor ligands: a promising new generation of pain therapeutics. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2017;32:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2016.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sriram K., Insel P.A. G protein-coupled receptors as targets for approved drugs: how many targets and how many drugs? Mol. Pharmacol. 2018;93:251–258. doi: 10.1124/mol.117.111062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoeber M., Jullie D., Lobingier B.T., Laeremans T., Steyaert J., Schiller P.W., Manglik A., von Zastrow M. A genetically encoded biosensor reveals location bias of opioid drug action. Neuron. 2018;98:963–976.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki J., El-Haddad S. A review: fentanyl and non-pharmaceutical fentanyls. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;171:107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urs N.M., Gee S.M., Pack T.F., McCorvy J.D., Evron T., Snyder J.C., Yang X., Rodriguiz R.M., Borrelli E., Wetsel W.C. Distinct cortical and striatal actions of a beta-arrestin-biased dopamine D2 receptor ligand reveal unique antipsychotic-like properties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2016;113:E8178–E8186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1614347113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wacker D., Stevens R.C., Roth B.L. How ligands illuminate GPCR molecular pharmacology. Cell. 2017;170:414–427. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J.T., Ingram S.L., Henderson G., Chavkin C., von Zastrow M., Schulz S., Koch T., Evans C.J., Christie M.J. Regulation of mu-opioid receptors: desensitization, phosphorylation, internalization, and tolerance. Pharmacol. Rev. 2013;65:223–254. doi: 10.1124/pr.112.005942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaki P.A., Keith D.E., Jr., Brine G.A., Carroll F.I., Evans C.J. Ligand-induced changes in surface mu-opioid receptor number: relationship to G protein activation? J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2000;292:1127–1134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L., Bohn L.M. Functional selectivity of GPCR signaling in animals. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2014;27:102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2013.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.