Sir,

We read with great interest the original article ‘Hypomorphic mutations in POLR3A are a frequent cause of sporadic and recessive spastic ataxia’ (Minnerop et al., 2017). In a large cohort of sporadic and recessive ataxia and spastic paraparesis, Minnerop et al. identified biallelic POLR3A variants in 3.1% (19/618) of the patients. Of these, 18 carried the intronic c.1909+22G>A variant, which was shown to activate a cryptic splice site, leading to a premature stop codon resulting in nonsense-mediated decay (NMD). On MRI, high intensities in the superior cerebellar peduncles were the main finding. The article prompted an interesting discussion regarding several aspects of this specific phenotype and genotype (Gauquelin et al., 2018; Minnerop et al., 2018), illustrating that confirmatory studies are warranted.

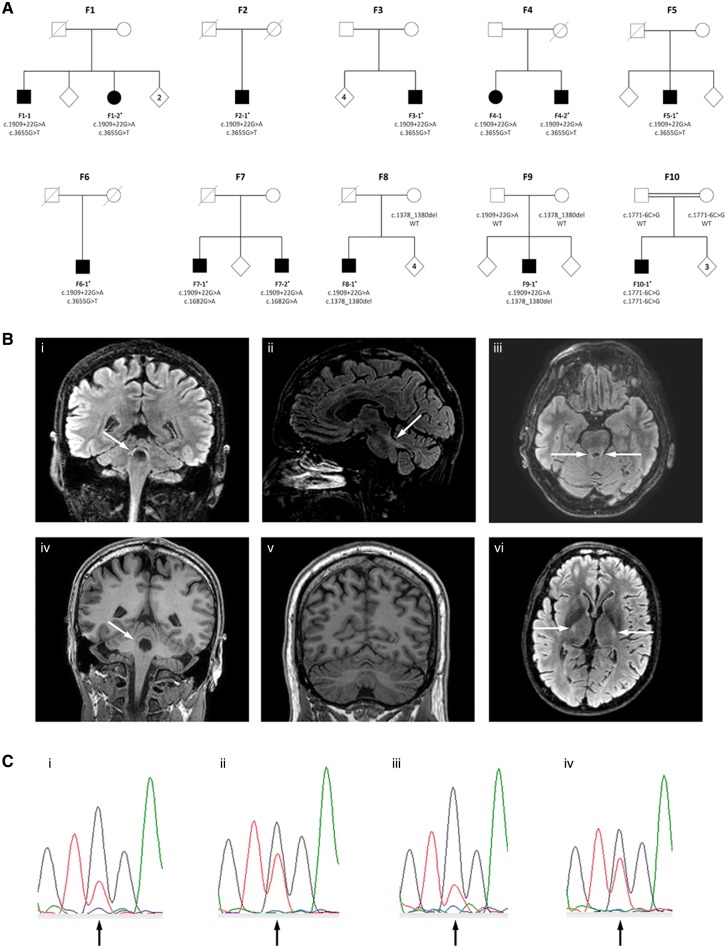

In this letter, we report the results of an independent study of patients with hereditary ataxia and spastic paraparesis (HSP) from Norway, confirming and elaborating the findings reported by Minnerop et al. In exome data from 95 Norwegian patients with a clinical diagnosis of ataxia or HSP without molecular diagnosis, we identified 10 probands and 13 patients with biallelic and presumed disease-causing POLR3A variants (Fig. 1A). The intronic c.1909+22G>A variant was identified in 9 of 10 families. For details on material and methods, see the online Supplementary material.

Figure 1.

Pedigrees, MRIs and sequencing chromatograms. (A) Pedigrees of the 10 families showing co-segregation of the variants and disease. In Families F1–F6 in trans status was confirmed by mRNA analyses, and in Families F7-F10 by sequencing of family members. In Family 7, the parents were not available for analyses, hence adult children were sequenced and found to carry only one of the variants each (results not included in the pedigree due to anonymity restrictions). Asterisks indicate that whole exome sequencing was performed. (B) MRI of the brain. (i–iv) The superior cerebellar peduncles of Patient F2–1 showing hyperintense signal in FLAIR MRI in coronal (i), sagittal (ii) and axial (iii) views, and isointense signal in T1-weighted coronal images (iv). Arrows indicate the superior cerebellar peduncles. (v) Coronal T1-weighted image of Patient F7–1 showing mild atrophy of the cerebellar vermis (midline) and hemispheres. (vi) Axial FLAIR image of Patient F8–1 showing hyperintense signal in the corticospinal tracts at the level of the posterior limb of the internal capsule (arrows). The MRI signal in all images was assessed in relation to the reference area in the caudate nucleus (Vrij-van den Bos et al., 2017). (C) Analysis of NMD of the c.3655G>T variant. Messenger RNA from lymphocytes cultured with and without inhibitor of NMD was reverse transcribed and amplified by PCR, followed by Sanger sequencing (details in the Supplementary material). The figure shows sequencing chromatograms of Patients F1–2 and F2–1. These patients carry the c.3655 G>T and c.1909+22G>A variants in trans, with the latter previously shown to result in a leaky splice site and partial NMD. The c.3655 position is marked by an arrow in the centre of each graph. [C(i and ii)] Chromatograms from analysis of Patient F1–2 without and with NMD inhibitor, respectively. [C(iii and iv)] Chromatograms from analysis of Patient F2–1 without and with NMD inhibitor, respectively. Notably, addition of NMD inhibitor led to increased amounts of product from the c.3655T allele as compared to the c.3655G allele. This result is consistent with complete NMD of the c.3655G>T variant, and partial degradation of transcripts from the c.1909+22G>A variant.

The patients presented with a remarkably recognizable phenotype combining neurological, dental and MRI findings, strikingly similar to the patients in the study by Minnerop et al. Detailed clinical characteristics of the patients are given in Table 1 and elaborated in Supplementary Table 1A. Mean age at onset of the first neurological symptoms was 13.7 years. In 12 of 13 patients symptoms began before the age of 21. The main neurological phenotype comprised ataxia (13/13), severe tremor of the neck/upper limbs (9/13), pyramidal signs in the lower limbs including bilateral extensor plantar responses (13/13), absent/reduced lower limb reflexes (12/13) and proprioceptive loss (12/13). Other neurological findings were lower limb weakness (12/13), muscle atrophy (11/12), reduced superficial sensations (7/13), dystonia (6/13) and urinary urgency (8/13). Interestingly, the tremor was alcohol-responsive. None had overt cognitive impairment. Neuropsychological evaluations in two patients showed well preserved cognitive function in one patient and a pattern compatible with mild cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome in the other (Schmahmann and Sherman, 1998).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the patients

| Patient ID | F1–1 | F1–2 | F2–1 | F3–1 | F4–1 | F4–2 | F5–1 | F6–1 | F7–1 | F7–2 | F8–1 | F9–1 | F10–1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variant 1 | c.1909+22G>A | c.1909+22G>A | c.1909+22G>A | c.1909+22G>A | c.1909+22G>A | c.1909+22G>A | c.1909+22G>A | c.1909+22G>A | c.1909+22G>A | c.1909+22G>A | c.1909+22G>A | c.1909+22G>A | c.1771–6C>G |

| Variant 2 | c.3655G>T | c.3655G>T | c.3655G>T | c.3655G>T | c.3655G>T | c.3655G>T | c.3655G>T | c.3655G>T | c.1682G>A | c.1682G>A | c.1378_1380del | c.1378_1380del | c.1771–6C>G |

| Gender | M | F | M | M | F | M | M | F | M | M | M | F | M |

| Age at onset, y | 5 | 14 | 12 | 17 | 20 | 13 | 30 | 10 | 11 | 20 | 17 | 5 | 4 |

| Disease duration, y | 62 | 51 | 35 | 27 | 28 | 33 | 15 | 55 | 46 | 29 | 28 | 24 | 41 |

| Neurological symptoms and findings | |||||||||||||

| SARA (0–40)/SPRS (0–52) | 29/34 | 24.5/25 | 28/33 | 22/22 | np | 17/18 | 7.5/11 | 27/21 | 17.5/28 | 11.5/18 | 16/23 | 5/np | np |

| LL spasticity/ reflexes | -/↓↓ | -/↓↓ | +/↓ | +/↓ | +/↓ | +/↓↓ | +/↓ | +/↓ | +/↓ | +/↑ | +/↓↓ | -/↓↓ | +/↓ |

| Extensor plantar responses | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| LL weakness/ atrophy | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/np | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | -/- | +/+ |

| Dysarthria | + | + | + | + | - | - | - | + | - | + | + | - | + |

| UL/LL ataxia | +/nt | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | -/+ | +/+ | +/- | +/+ | -/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ | +/+ |

| Postural tremor UL | + | + | + | + | - | - | - | + | - | - | + | - | + |

| Head and neck titubation/dystonia | +/- | +/- | +/- | +/+ | -/- | +/+ | -/- | +/+ | -/- | -/- | -/+ | +/+ | +/+ |

| LL vibration/surface sensation | ↓↓/↓ | ↓↓/↓ | ↓↓/↓ | N/N | ↓/↓ | ↓/N | ↓↓/↓ | ↓↓/N | ↓↓/↓ | ↓↓/N | ↓↓/↓↓ | ↓/N | ↓↓/N |

| Urinary urgency | + | + | + | - | + | - | + | - | + | + | + | - | - |

| Non-neurological findings | |||||||||||||

| Dental abnormalities | + | + | + | + | np | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Myopia | - | - | + | - | np | - | - | + | + | - | + | + | - |

| Hypogonadism | np | - | - | - | np | - | - | - | - | - | + | np | - |

| Neurophysiology | |||||||||||||

| Polyneuropathy | np | - | nt | - | np | + | - | - | + | - | - | - | - |

| Abnormal SEP/BAEP/VEP | np | +/-/- | -/+/- | +/+/- | np | nt/+/nt | np | nt/nt/- | +/+/- | +/+/- | +/+/- | -/np/- | np |

| MRI | |||||||||||||

| SCP hyperintensity (FLAIR) | np | + | + | + | np | + | + | nt | + | + | + | + | + |

| Thin cervical spinal cord | np | + | + | + | np | + | + | nt | + | + | + | + | + |

| Thinning of corpus callosum | np | - | - | - | np | - | - | nt | - | - | - | - | - |

| Total white matter scorea | np | 3 | 6 | 6 | np | nt | 2 | nt | 3 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 1 |

| Total atrophy scorea | np | 2 | 3 | 1 | np | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

+ = present; - = absent; ↑ = increased; ↓ = reduced; ↓↓ = absent; LL = lower limbs; N = normal; np = not performed/not available; nt = not testable due to tremor/other co-morbidity; SARA = Scale for Assessment and Rating of Ataxia (Schmitz-Hubsch et al., 2006); SCP = superior cerebellar peduncles; SEP/BAEP/VEP = somatosensory/brain stem auditory/visual evoked potentials; SNAP = sensory nerve action potentials; SPRS = Spastic Paraplegia Rating Scale (Schule et al., 2006); UL = upper limbs.

aFollowing the 4H Leukodystrophy Brain MRI Scoring System. Total white matter score = 0–44; Total atrophy score = 0–10 (Vrij-van den Bos et al., 2017).

Concerning non-neurological features, which were central in the previous debate, our findings are in line with those of Minnerop et al. Dental abnormalities were present in 11/13 patients, including hypodontia, retention of teeth, short dental roots, early dental loss and/or early periodontal disease. Also, one of the patients had developed several superfluous permanent teeth. Myopia was reported in 5 of 12 patients. Patient F9–1 had high myopia (<−6.00 dioptres), possibly a feature of her POLR3A-related syndrome. Four patients had milder myopia (>−3.00 dioptres), which is also a common finding in the general population (Williams et al., 2015). Optic atrophy was not observed (0/7). Short stature and hormonal dysfunction were not prominent findings in our patient group. None had short stature (as defined by males <166 cm, females <153 cm) and height did not differ compared to other family members. Gonadal dysfunction was identified in one patient. Notably, in most patients, dental problems or hormonal dysfunction were not reported until specifically asked for.

Minnerop et al. introduced neuropathy as a clinical feature of POLR3A-related syndromes, describing abnormal nerve conduction studies (6/20), reduced vibration (23/24) and/or surface sensations (15/24). All patients in our study had severe sensory deficits, mainly of joint position and vibration sense, and 7/13 had markedly reduced surface sensations. Absent reflexes and muscle atrophy suggest dysfunction of peripheral nerves. Nerve conduction studies showed mild axonal sensory neuropathy in 2 of 10 investigated patients (from 2 of 10 patients), and 5 of 10 had mononeuropathies, but none had motor polyneuropathy. Similar to Minnerop et al., we found abnormal somatosensory evoked responses in most patients (5/7), indicating dysfunction of ‘central’ sensory pathways. Brainstem auditory evoked responses were also abnormal in most patients (6/7).

MRI was available in 10 patients, seven performed on 3 T MRI. Bilateral hyperintensity along the superior cerebellar peduncles on FLAIR images (Fig. 1B) was found in all patients, consistent with the main finding reported by Minnerop et al., and thus represents a convincing radiological clue for the diagnosis. To evaluate hypomyelination and atrophy, the 4H leukodystrophy brain MRI scoring system was used (Vrij-van den Bos et al., 2017). Mild hypomyelination in other brain areas, represented by iso- or hyperintense T2 signals were also identified; in particular of the pyramidal tracts at the level of the internal capsule (9/9). In addition, 9 of 10 patients showed mild cerebellar atrophy and 10 of 10 had slight thinning of the cervical spinal cord, compatible with previous reports (La Piana et al., 2014, 2016), whereas none had thinning of the corpus callosum. Median total MRI score was 5 out of a possible maximum of 54 (range 4–9, mean 5.8), representing a mild degree of hypomyelination and atrophy. In comparison, Vrij-van den Bos et al. (2017) found a much higher score (median of 31) in patients with 4H leukodystrophy.

Five different presumed pathogenic variants in POLR3A were identified (Table 1). The variants were confirmed to be in trans in all 13 patients. The intronic c.1909+22G>A variant was found in 12, whereas one patient (Patient F10–1) was homozygous for the previously reported intronic c.1771–6C>G variant (Azmanov et al., 2016). Furthermore, we identified three novel variants. In six families (Families F1–F6) we identified the variant c.3655G>T, p.Gly1219*, which leads to NMD of the mRNA transcript (Fig. 1C and Supplementary material). Another novel variant c.1682G>A, p.Arg561Gln was found in one family (Family F7). Structural analysis showed that this variant may disturb the interactions of the subunits POLR2H and the heterodimer POLR2C/POLR2J, and thereby affect the enzymatic activity of Pol III. Lastly, a deletion of three base pairs (c.1378_1380del, p.Val460del) was identified in two families (Families F8 and F9). It deletes a valine in a conserved area of the protein and is likely to destabilize the POLR3A subunit.

Haplotype analyses of exome data surrounding the POLR3A gene, revealed a maximal possible length of a common haplotype shared by the probands carrying c.1909+22G>A or c.3655G>T, of 1.9 Mb. The absence of longer shared haplotypes makes it unlikely that any of the two variants has a single recent founder. We could not identify any obvious genotype-phenotype correlations in our study. However, the patients carrying the c.1378_1380del had more prominent extra-neurological features.

Importantly, biallelic variants in POLR3A were found to be the second most common cause of recessive ataxia or HSP in our Norwegian cohort of 521 probands, second only to Friedreich’s ataxia (Wedding et al., 2015). In this cohort, 322 probands were classified with autosomal recessive or sporadic ataxia or HSP. Even if less than a third of these probands had exome data available for POLR3A analysis in this study, the 10 identified individuals with biallelic variants in POLR3A represent a frequency of 3.1%, similar to the frequency found by Minnerop et al. (2017). No additional carriers of the c.1909+22G>A variant were identified in the 95 exomes. However, our sample size is small and could be prone to several aspects of selection bias, and we thus regard it unsuitable for extrapolating any association (or lack of association) of this variant with ataxia/HSP to a general population of ataxia/HSP. Hence, a properly designed association study would be required to replicate the association results previously reported (Minnerop et al., 2017; Gauqelin et al., 2018).

In summary, our study confirms that biallelic variants in POLR3A are indeed a frequent cause of disease in hereditary ataxia/HSP patients. In particular, the c.1909+22G>A variant is prevalent, illustrating the importance and complexity of variants in non-coding regions. Furthermore, we delineate a highly characteristic and consistent clinical picture, comprising early onset ataxia with or without tremor, combined with pyramidal and posterior column findings, dental abnormalities and the key MRI finding of high intensities along the superior cerebellar peduncles. The expanding phenotypic spectrum of POLR3A-related syndromes, now including leukodystrophies, a disease of premature ageing—Wiedemann-Rautenstrauch syndrome (Paolacci et al., 2018)—and hereditary ataxia/HSP, calls for future disease classification which includes both clinical and genetic information (Rossi et al., 2018), and for increased awareness of also atypical non-neurological symptoms in complex neurological disorders.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the letter and its Supplementary material.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and their family for participating in this study. We also thank the Departments of Neurology and Departments of Medical Genetics at Telemark Hospital and The University Hospital of Northern Norway, and the Department of Medical Genetics, Oslo University Hospital.

Funding

K.K.S. was supported by South Eastern Health region grants (grant 2014018) and P.H.B. by the Southeastern Norway Regional Health Authorities Technology Platform for Structural Biology (grant 2015095).

Competing interests

The authors report no competing interests.

References

- Azmanov DN, Siira SJ, Chamova T, Kaprelyan A, Guergueltcheva V, Shearwood AJ, et al. Transcriptome-wide effects of a POLR3A gene mutation in patients with an unusual phenotype of striatal involvement. Hum Mol Genet 2016; 25: 4302–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauquelin L, Tetreault M, Thiffault I, Farrow E, Miller N, Yoo B, et al. POLR3A variants in hereditary spastic paraplegia and ataxia. Brain 2018; 141: e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Piana R, Cayami FK, Tran LT, Guerrero K, van Spaendonk R, Ounap K, et al. Diffuse hypomyelination is not obligate for POLR3-related disorders. Neurology 2016; 86: 1622–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Piana R, Tonduti D, Gordish Dressman H, Schmidt JL, Murnick J, Brais B, et al. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) pattern recognition in Pol III-related leukodystrophies. J Child Neurol 2014; 29: 214–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minnerop M, Kurzwelly D, Rattay TW, Timmann D, Hengel H, Synofzik M, et al. Reply: POLR3A variants in hereditary spastic paraplegia and ataxia. Brain 2018; 141: e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minnerop M, Kurzwelly D, Wagner H, Soehn AS, Reichbauer J, Tao F, et al. Hypomorphic mutations in POLR3A are a frequent cause of sporadic and recessive spastic ataxia. Brain 2017; 140: 1561–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paolacci S, Li Y, Agolini E, Bellacchio E, Arboleda-Bustos CE, Carrero D, et al. Specific combinations of biallelic POLR3A variants cause Wiedemann-Rautenstrauch syndrome. J Med Genet 2018; 55: 837–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi M, Anheim M, Durr A, Klein C, Koenig M, Synofzik M, et al. The genetic nomenclature of recessive cerebellar ataxias. Mov Disord 2018; 33: 1056–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmahmann JD, Sherman JC. The cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome. Brain 1998; 121: 561–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz-Hubsch T, du Montcel ST, Baliko L, Berciano J, Boesch S, Depondt C, et al. Scale for the assessment and rating of ataxia: development of a new clinical scale. Neurology 2006; 66: 1717–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schule R, Holland-Letz T, Klimpe S, Kassubek J, Klopstock T, Mall V, et al. The Spastic Paraplegia Rating Scale (SPRS): a reliable and valid measure of disease severity. Neurology 2006; 67: 430–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrij-van den Bos S, Hol JA, La Piana R, Harting I, Vanderver A, Barkhof F, et al. 4H leukodystrophy: a brain magnetic resonance imaging scoring system. Neuropediatrics 2017; 48: 152–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wedding IM, Kroken M, Henriksen SP, Selmer KK, Fiskerstrand T, Knappskog PM, et al. Friedreich ataxia in Norway—an epidemiological, molecular and clinical study. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2015; 10: 108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams KM, Bertelsen G, Cumberland P, Wolfram C, Verhoeven VJ, Anastasopoulos E, et al. Increasing prevalence of myopia in Europe and the impact of education. Ophthalmology 2015; 122: 1489–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the letter and its Supplementary material.