Abstract

Biopolymeric hydrogels have been widely used as carriers of therapeutic cells and drugs for biomedical applications. However, most conventional hydrogels cannot be injected after gelation and do not support the infiltration of cells because of the static nature of their network structure. Here, we develop unique cell-infiltratable and injectable (Ci-I) gelatin hydrogels, which are physically cross-linked by weak and highly dynamic host–guest complexations and are further reinforced by limited chemical cross-linking for enhanced stability, and then demonstrate the outstanding properties of these Ci-I gelatin hydrogels. The highly dynamic network of Ci-I hydrogels allows injection of prefabricated hydrogels with encapsulated cells and drugs, thereby simplifying administration during surgery. Furthermore, the reversible nature of the weak host–guest cross-links enables infiltration and migration of external cells into Ci-I gelatin hydrogels, thereby promoting the participation of endogenous cells in the healing process. Our findings show that Ci-I hydrogels can mediate sustained delivery of small hydrophobic molecular drugs (e.g., icaritin) to boost differentiation of stem cells while avoiding the adverse effects (e.g., in treatment of bone necrosis) associated with high drug dosage. The injection of Ci-I hydrogels encapsulating mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and drug (icaritin) efficiently prevented the decrease in bone mineral density (BMD) and promoted in situ bone regeneration in an animal model of steroid-associated osteonecrosis (SAON) of the hip by creating the microenvironment favoring the osteogenic differentiation of MSCs, including the recruited endogenous cells. We believe that this is the first demonstration on applying injectable hydrogels as effective carriers of therapeutic cargo for treating dysfunctions in deep and enclosed anatomical sites via a minimally invasive procedure.

Short abstract

The cell-infiltratable and injectable (Ci-I) hydrogel is a promising carrier biomaterial for treating dysfunctions in deep and enclosed anatomical sites via a minimally invasive procedure.

Introduction

Various natural and synthetic materials have been used as potential carrier biomaterials of cell or therapeutic agents for tissue regeneration.1−6 Hydrogels with highly hydrated polymeric networks are ideal carriers for encapsulating cells and drugs.7−12 However, most conventional hydrogels that allow cells encapsulation are based on static chemical cross-linking and lack dynamic properties such as self-healing and injectability.13−15 These limitations preclude the delivery of cargo agents by the hydrogel carriers to anatomically deep and enclosed defects via minimally invasive procedures, which have become increasingly popular because of demands for aesthetic appearance and expeditious postsurgery recovery.16 Furthermore, the rigid and nondegradable nature of chemically cross-linked hydrogels hinders the recruitment and infiltration of host cells into implanted hydrogels, thereby limiting the extent of in situ regeneration and integration of implanted biomaterials into host tissues.17,18

Many previous studies have demonstrated the fabrication of dynamic hydrogels stabilized by reversible physical cross-linking including hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions, ionic interactions, ligand–ion coordination, dipole–dipole interactions, and host–guest complexations.19−37 These physically cross-linked hydrogels exhibit many desirable properties including self-healing and injectability.38−44 However, because of the weak nature of physical cross-linking and the stringent demands of cell-friendly preparation, few studies have reported physical hydrogels that are sufficiently cytocompatible and stable to allow for encapsulation and long-term culture of cells and to provide continued support to the encapsulated cells in vivo after delivery.

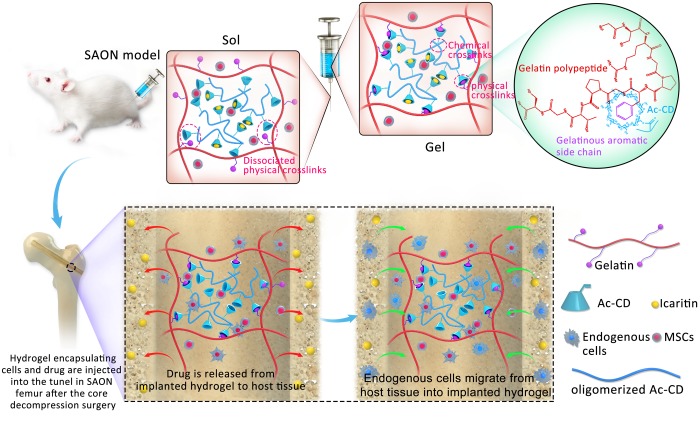

In this study, we develop unique cell-infiltratable and injectable (Ci-I) gelatin hydrogels, which are stabilized largely by the physical cross-linking of host–guest complexation and are further reinforced by limited chemical cross-linking (Scheme 1), and then demonstrate the outstanding properties of these Ci-I gelatin hydrogels. Our Ci-I gelatin hydrogels can be preformed with encapsulated therapeutic cells and drugs first, maintained under culture conditions for a desired period, and injected to target sites in the gel form at a prescribed time because of their excellent injectability and remoldability. Furthermore, the reversible physical cross-links of the Ci-I hydrogels also support infiltration of cells into the hydrogels that are loaded with chemoattractant drugs. These unique capabilities of Ci-I hydrogels offer great convenience during surgical procedures and significantly expedite clinical operations. We further evaluated the efficacy of the Ci-I gelation hydrogels as carriers of therapeutic drugs and cells for treating an enclosed bone abnormality in steroid-associated osteonecrosis (SAON) of the femoral head.

Scheme 1. Preparation of the Cell-Infiltratable and Injectable (Ci-I) Gelatin Hydrogels and the Treatment of SAON with Ci-I Hydrogels as the Carrier of Therapeutic Cargoes (Cells and Drug) in the Rat Model.

Steroids are widely used for treating various clinical conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis, organ transplantation, and respiratory syndrome.45−49 However, long-term steroid treatments may lead to SAON, commonly affecting large joints such as the hip.50−52 A surgical core decompression (CD) procedure is typically performed on patients with early stage SAON to remove the necrotic bone and implant bone substitute in the drilled tunnel to prevent subsequent decreases in bone mineral density and support bone regeneration.53,54 Since the lack of endogenous stem cells and aberrant accumulation of adipose tissues were recognized as main characteristics of SAON in previous studies,55,56 here, we evaluated the feasibility of the Ci-I gelatin hydrogels encapsulating mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and a hydrophobic small molecule, icaritin, as a bone substitute to treat rat SAON (Scheme 1). Our in vivo animal research showed that the MSCs and icaritin-laden Ci-I gelatin hydrogels can prevent a decrease in bone mineral density (BMD) and promote in situ bone regeneration. Moreover, the icaritin-laden hydrogels enhanced the recruitment and infiltration of cells from the surrounding host tissues to the implantation sites, further confirming the efficacy of our Ci-I hydrogels for promoting in situ regeneration. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study demonstrating the feasibility of using injectable hydrogels encapsulating stem cells and small molecules to treat bone disorders in deep and enclosed anatomical locations, e.g., SAON at the hip.

Results and Discussion

Prefabricated Ci-I Hydrogels Adapt to Injection Site Geometry and Maintain Initial Mechanical Properties after Injection

Gelatin has been extensively used for various biomedical applications because of its biocompatibility, bioactivity, biodegradability, and availability.57,58 Gelatin hydrogels are especially useful as carrier materials of therapeutic cells and drugs.59−61 However, the preparation of conventional chemically cross-linked gelatin hydrogels entails chemical modifications of the gelatin, and the obtained hydrogels are brittle with restricted network dynamics.62−64 Therefore, in this study, we developed a strategy to prepare gelatin hydrogels containing both chemical and physical cross-linking based on unmodified gelatin. First, the synthesized free diffusing photo-cross-linkable Ac-β-CDs (acryloyl β-cyclodextrin, 1.5 acryloyl groups per Ac-β-CD molecule on average, i.e., a fraction of Ac-β-CDs bear more than one acryloyl group, Figure S1) were coupled to the aromatic residues of gelatin (e.g., phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan) via host–guest interactions. Subsequently, UV-initiated polymerization of the Ac-β-CDs led to the formation of gelatin hydrogels containing two types of cross-links: (1) the physical host–guest complexations between the aromatic residues of the gelatin and oligomerized Ac-β-CDs, which are distributed throughout the entire hydrogel network; and (2) the chemical cross-links (due to the fraction of Ac-β-CDs bearing more than one acryloyl group) among the oligomerized Ac-β-CDs, the distribution of which is sparse and localized because of the inefficient reaction among the bulky Ac-β-CDs. The following experiments demonstrated that these gelatin hydrogels not only possessed unique dynamic properties including self-healing, shear-thinning, injectability, and cell infiltration capability due to the physical host–guest cross-linking but also showed adequate stability because of the localized chemical cross-linking for supporting long-term 3D culture of encapsulated cells. These hydrogels are therefore referred to as the “cell-infiltratable and injectable gelatin hydrogels” (Ci-I gelatin hydrogels) in the following sections.

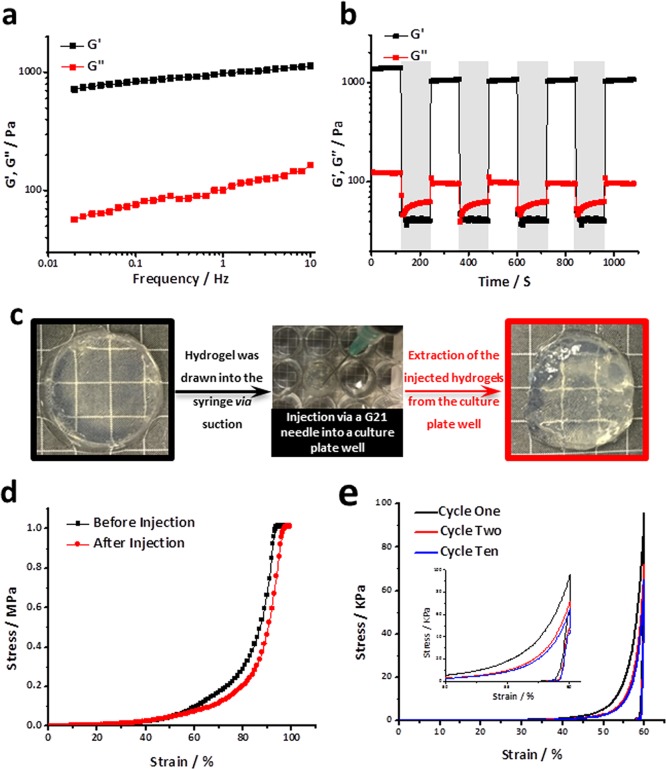

The rheological measurements further demonstrated the presence of both physical and chemical cross-linking within the Ci-I gelatin hydrogels. The Ci-I hydrogels showed an obvious frequency-dependent increase in the modulus (Figure 1a), indicating the involvement of the physical host–guest complexation between gelatinous aromatic groups and β-CDs in stabilizing the hydrogel network. The further rheological studies revealed a “sol–gel” transition of the Ci-I hydrogels under alternating high/low shear strain (Scheme 1). The Ci-I hydrogels switched to the “sol” state (G″ > G′) under a high shear strain of ∼1000% and immediately recovered to the “gel” state (G′ > G″) under a subsequent low shear strain of 1% (Figure 1b). Moreover, even after repeated high/low shear loading cycles, the storage modulus (G′) of the Ci-I hydrogels consistently recovered to ∼80% (1050 Pa) of that of the freshly prepared unloaded samples (1373 Pa) (Figure 1b). This slight reduction in storage modulus is likely attributed to the partial disruption of chemical cross-linking under loading. This excellent shear-thinning and self-healing capability enables the injection of Ci-I hydrogels without significantly compromising their mechanical properties. The prefabricated Ci-I hydrogel disks injected through a G21 needle into cylindrical models were efficiently remolded to regain the original disk morphology (Figure 1c). Moreover, the compression test showed that the injection did not significantly affect the mechanical properties of the Ci-I gelatin hydrogels, and the injected hydrogels could still sustain over 95% compressive strain without rupture as could the noninjected hydrogels (Figure 1d). Furthermore, after the first loading–unloading cycle, the Ci-I hydrogels exhibited almost coinciding loading–unloading stress versus strain curves obtained from the remaining loading cycles (peak strain: 60%), suggesting excellent resistance to excessive cyclic compression (Figure 1e). Previous studies65−68 proved that well-designed injectable hydrogels could prevent encapsulated cells from damage of shear force during the injection through the syringe needle. To study whether our Ci-I gelatin hydrogels could maintain the viability of the encapsulated cell during the injection, we cultured hMSC-laden Ci-I gelatin hydrogels in vitro for 1 day before injecting the hydrogels through a G21 needle, and the injected hydrogels were further cultured in vitro for another 5 days. Figure S3 shows that the cell viability is still >90% even after injection, demonstrating the effective protection of the encapsulated cells by the injectable Ci-I gelatin hydrogels.

Figure 1.

(a) Ci-I gelatin hydrogels displayed a frequency-dependent response in the rheological frequency sweep test at a strain of 0.1% and 37 °C. (b) Ci-I hydrogels exhibited a sol–gel transition during switching between alternating high (1000%, unshaded region) and low (1%, shaded region) shear strain in the rheological test at 37 °C. (c) A preformed Ci-I gelatin hydrogel was drawn into a syringe and then injected through a G21 needle into a culture plate well (used as the mold) to be remolded to the shape of the cell culture well. (d) Ci-I gelatin hydrogels sustained over 95% of compressive strain without rupture before or after injection. (e) Stress vs strain curves from a cyclic compression test of Ci-I hydrogels (peak strain, 60%; loading speed, 1 mm/s) at 37 °C (inset: plot in the strain range 50–60%).

Ci-I Hydrogels Mediate Sustained Delivery of a Hydrophobic Chemoattractant and Support Infiltration of Cells

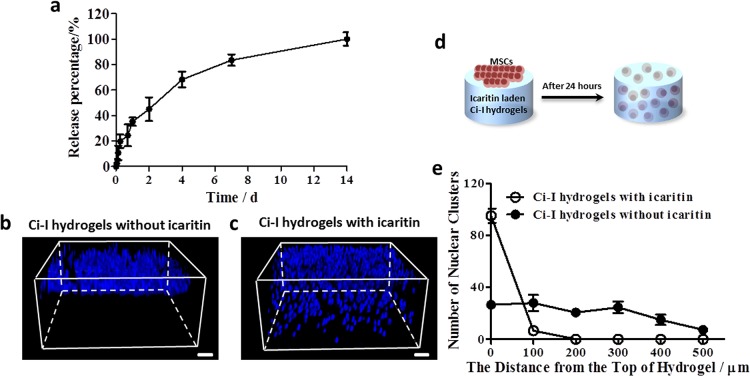

Sustained delivery of small hydrophobic molecules via hydrogels is typically challenging because the hydrophilic nature and large mesh size of hydrogel networks make loading and long-term release of small hydrophobic molecules rather difficult. Because a significant excess of Ac-β-CDs (compared with gelatinous aromatic residues) were used to fabricate Ci-I hydrogels, there were a considerable number of unoccupied β-CD moieties conjugated to the hydrogel network. β-CD is commonly used in the pharmaceutical industry to improve the solubility of hydrophobic drugs.69−71 We utilized the empty β-CD cavities in Ci-I hydrogels to deliver a small hydrophobic chemical molecule, icaritin, which can reduce SAON incidence by inhibiting both thrombosis and lipid deposition.72 The icaritin-laden Ci-I gelatin hydrogels were capable of releasing icaritin continuously for up to 2 weeks (Figure 2a). Therefore, these findings demonstrate that the injectable Ci-I gelation hydrogels can serve as a promising delivery vehicle of small hydrophobic molecular drugs for treating pathological conditions including SAON in a minimally invasive fashion.

Figure 2.

(a) Kinetics of small-molecule icaritin release from the Ci-I gelatin hydrogels at 37 °C. The confocal micrographs show the 3D distribution of DAPI-stained human mesenchymal stem cell (hMSC) nuclei within the Ci-I hydrogels without (b) or with (c) icaritin encapsulation after 24 h of in vitro culture. (d) Schematic illustration of a cell migration experiment at 37 °C. hMSCs seeded on the surface of the icaritin-laden Ci-I gelatin hydrogels infiltrated into the hydrogels within 24 h. (e) Invasion distance of DAPI-stained hMSC nuclei clusters within the Ci-I gelatin hydrogels without icaritin and Ci-I gelatin hydrogels with icaritin. The thickness of the Ci-I hydrogels used for the cell migration test is 1 mm, and the scanning depth of the Ci-I hydrogels is 500 μm in the cell migration experiments. Scale bar: 100 μm (parts b and c).

Our previous research also showed that an anabolic and potent molecule icaritin can function as a chemoattractant to induce the directed migration of MSCs within a short time frame.72 The dynamic and weak cross-links based on host–guest complexation of our Ci-I gelatin hydrogel can potentially support cell infiltration and migration. To demonstrate this, we seeded MSCs on the surface of Ci-I hydrogels with or without the loaded icaritin. After 24 h of culture, most MSCs still remained on top of the hydrogels without icaritin (Figure 2b,e and Movie S1), whereas nearly all MSCs infiltrated and migrated into the hydrogels loaded with icaritin (Figure 2c–e and Movie S2). The degradation of the hydrogels by cell-secreted catabolic enzymes might not be significant enough to support such extensive cell infiltration within the short period of 24 h. We speculated that the cell infiltration was likely facilitated by the disruption of the weak host–guest cross-links in Ci-I hydrogels by cellular forces. Therefore, we speculate that, once implanted into the defect sites, the icaritin-laden Ci-I gelatin hydrogels can promote the recruitment and infiltration of endogenous cells into the hydrogel matrix, thereby speeding up the repair and regeneration of bone defects.

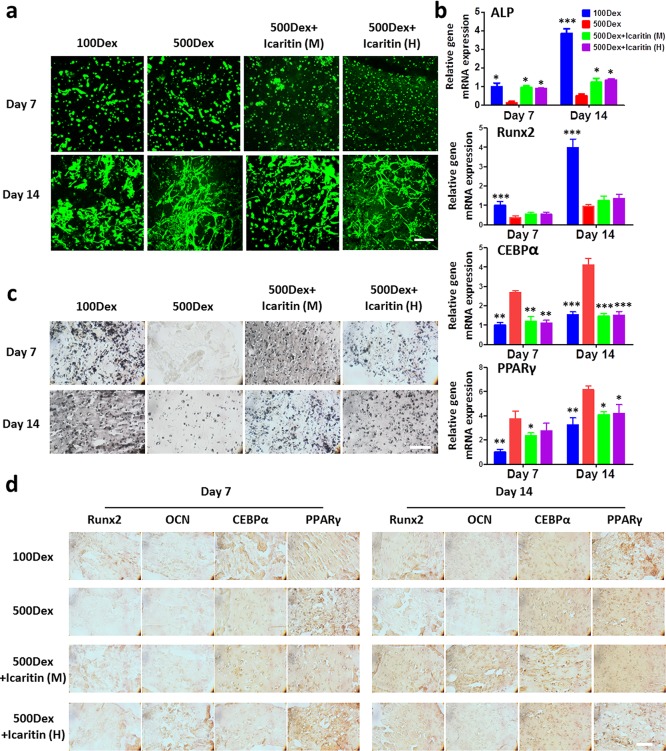

Ci-I Hydrogel Attenuates the Adverse Effect of High-Dosage Corticosteroid during Stem Cell Differentiation

We then evaluated the efficacy of the Ci-I hydrogel as an injectable carrier of therapeutic cells to treat SAON by examining the osteogenesis of MSCs encapsulated in the Ci-I gelatin hydrogels in the presence of a high concentration of corticosteroid. The majority of MSCs encapsulated in the Ci-I gelatin hydrogels were viable and spread to adopt a stellate morphology after 2 weeks of culture (Figure 3a), indicating that the dynamic Ci-I hydrogel network provides a permissive 3D environment to facilitate cell–matrix interactions. Then, we evaluated the differentiation of MSCs encapsulated in hydrogels under different culture conditions. Previous studies showed that dexamethasone (Dex), a clinically used corticosteroid, improved the osteogenesis of MSCs at low concentration but promoted the adipogenesis of MSCs at high concentration.73,74 Our RT-PCR data indeed showed that a low media concentration of Dex (100 nM, “100Dex”) promoted the expression of osteogenic markers (ALP and Runx2), whereas a high media concentration (500 nM, “500Dex”) of Dex up-regulated the expression of adipogenic markers of the MSCs encapsulated in hydrogels (CEBPα and PPARγ) (Figure 3b). In contrast, media supplementation of icaritin effectively suppressed the expression of adipogenic marker genes and promoted that of osteogenic marker gene, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), of the encapsulated MSCs under a high media concentration of Dex (Figure 3b, “500Dex+icaritin (M)”). The upregulation of another osteogenic marker gene Runx2 is insignificant. We speculated that it was because the Runx2 gene expression data were collected at late time points, day 7 and 14, while the Runx2 is typically upregulated in MSCs at early time points upon osteogenic induction, and correlation between osteogenesis of MSCs and Runx2 expression becomes less significant at late time points.75 Furthermore, the Ci-I gelatin hydrogels that were loaded with a bolus dose of icaritin (“500Dex+icaritin (H)”) without icaritin supplementation produced similar expression levels of the differentiation marker genes as those of “500Dex+icaritin (M)”, which received fresh icaritin supplementation after each media change (Figure 3b). Von Kossa staining (Figure 3c) and the Runx2, OCN, CEBPα, and PPARγ immunohistochemical staining (Figure 3d) showed trends consistent with that of the RT-PCR. These results demonstrate that the Ci-I gelatin hydrogels are likely capable of mediating sustained delivery of small hydrophobic molecular drugs (e.g., icaritin) to counteract the adverse effects (e.g., bone necrosis) of high-concentration corticosteroids in the long term.

Figure 3.

(a) Cell viability staining (green corresponds to live cells, and red corresponds to dead cells) of MSC-laden Ci-I gelatin hydrogels after 1 week and 2 weeks of culture. (b) Gene expression of selected osteogenic markers (alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and Runx2) and adipogenic markers (CEBPα and PPARγ) of MSCs encapsulated in Ci-I gelatin hydrogels after 7 and 14 days of culture. Each sample was internally normalized to GAPDH, and every group was compared to the expression levels of group 100Dex on day 7, the quantitative value of which was set to unity. The data were analyzed with two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test (n = 4, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, compared to the 500Dex group). (c) Von Kossa staining; (d) immunohistochemical staining of Runx2, OCN, CEBPα, and PPARγ of the hMSCs loaded in Ci-I gelatin hydrogels after 7 and 14 days of culture. 100Dex, 100 nM dexamethasone (Dex) in media; 500Dex, 500 nM Dex in media; 500Dex+icaritin (M), 500 nM Dex and 1 mM icaritin in media; 500Dex+icaritin (H), 500 nM Dex in media and 1.3 mM icaritin in the hydrogel. The total amount of icaritin in the 500Dex+icaritin (M) group is the same as that in the 500Dex+icaritin (H) group. Scale bar: 100 μm (parts a, c, and d).

Codelivery of MSC and Icaritin via Ci-I Hydrogels Enhances Bone Regeneration in SAON Model

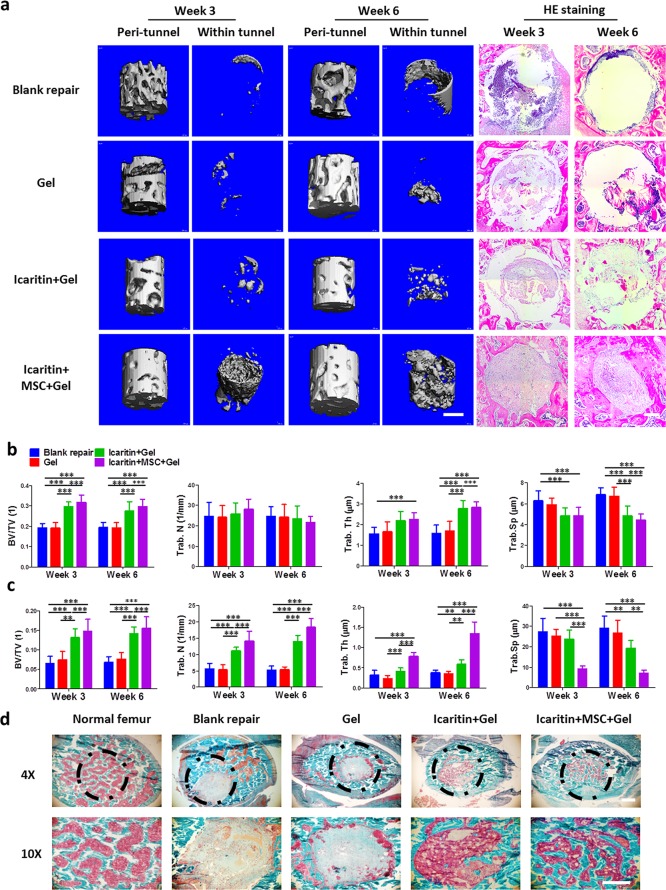

We further evaluated the efficacy of Ci-I gelatin hydrogels encapsulated with MSCs and icaritin to boost bone regeneration in a SAON model. Figure 4a showed that the injection of Ci-I gelatin hydrogels helped to prevent a decrease in BMD around the tunnel compared to the nontreated control group (no hydrogel implantation, “Blank”). The “icaritin+MSC+Gel” group showed significantly enhanced new bone formation in the tunnel (Figure 4a). Quantitative measurement of the micro-CT images showed that the “icaritin+MSC+Gel” group exhibited significant elevation in BV/TV, trabecular number, while trabecular thickness and a reduction in trabecular separation, as compared to the other groups, in both the peri-tunnel native bone (Figure 4b) and neobone tissue inside the tunnel (Figure 4c). Using Goldener’s Trichrome staining, we also further confirmed that the bone tunnel was filled with neobone in the “icaritin+MSC+Gel” group (Figure 4d). In contrast, only fibrous tissue was formed in the other groups without supplementation of icaritin (Figure 4d).

Figure 4.

(a) Micro-CT images and HE staining of the native bone around the tunnel and the new bone inside the tunnel after 3 and 6 weeks postinjection of Ci-I hydrogels in SAON rats. Quantitative analysis of micro-CT for the bone in the “peri-tunnel” (b) and “within tunnel” (c) space. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc tests were used to analyze the data (n = 6, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). (d) Goldener’s Trichrome staining of the bonelike tissue within the bone tunnel. Scale bar: 500 μm (micro-CT images in part a); 100 μm (HE staining in part a and Goldener’s staining in part d).

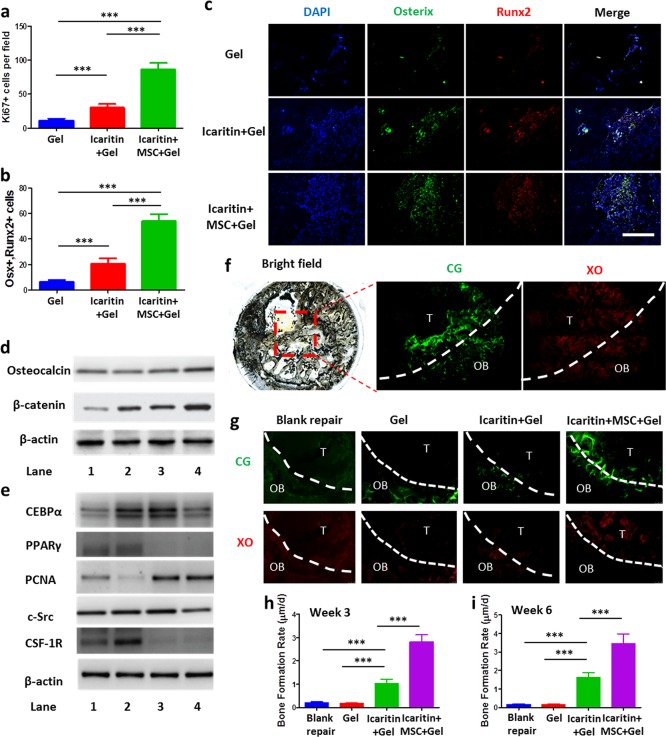

We further examined the harvested samples to assess the bone regeneration within the drilled tunnel. Immunofluorescent staining against Ki67, a marker widely used to identify proliferating cells, showed significantly more Ki67 positive cells in the tunnel region injected with the Ci-I gelatin hydrogels, which were loaded with both MSCs and icaritin (“icaritin+MSC+Gel”), as compared to that of either hydrogel alone (“Gel”) or hydrogel plus icaritin (“icaritin+Gel”) treatment groups (Figure 5a). Moreover, the “icaritin+MSC+Gel” group also exhibited the most intense staining against key osteogenic markers, Runx2 and Osterix (Figure 5b,c). At week 3 after the hydrogel implantation, the expressions of active β-catenin and OCN were upregulated in the “icaritin+MSC+Gel” group (Figure 5d and Figure S6a) compared to those of the other groups, and this may have contributed to the enhanced bone formation. In contrast, PPARγ expression was dramatically decreased (Figure 5e and Figure S6b), indicating suppressed adipogenesis, and this is consistent with our previous in vitro findings (Figure 3d). The icaritin-laden hydrogels (“icaritin+MSC+Gel” and “icaritin+Gel”) also exhibited significantly elevated expression of another proliferation marker, proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), in addition to Ki67 at week 6 (Figure 5a and Figure S4), regardless of MSC supplementation. In addition, the “icaritin+MSC+Gel” group showed slightly reduced expression of c-Src, a detrimental factor that has been identified as a therapeutic target for osteonecrosis.55 CSF-1R, a tyrosine-kinase transmembrane receptor,76 was greatly reduced in the “icaritin+MSC+Gel” and “icaritin+Gel” groups, indicating the potential immunoregulative effect of icaritin, as reported by a previous study.77 More importantly, this finding suggests that icaritin and MSCs delivered by Ci-I hydrogels can potentially mitigate the foreign body response to biomaterial implantations, thereby facilitating further translational applications.76 By using calcein green (CG) and xylenol orange (XO) to dynamically assess the bone formation rate, at week 3 and 6 postsurgery we found that treatment with hydrogel alone (“Gel”) did not affect bone formation within the bone tunnel (Figure 5f–i). Incorporation of icaritin in the injected hydrogels (“icaritin+Gel”) significantly increased the bone formation rate compared to either blank repair or the “Gel” group (Figure 5f–i). The encapsulation of both exogenous MSCs and icaritin in the hydrogels (“icaritin+MSC+Gel”) further enhanced bone formation in the defect site (Figure 5f–i). These data demonstrate that the Ci-I gelatin hydrogel is an excellent carrier of cells and hydrophobic drugs for promoting in situ bone regeneration and treating SAON.

Figure 5.

(a) Quantitative analysis of cells positive for Ki67 (Figure S4 for corresponding images) and (b) cells positive for both Osterix and Runx2 using immunofluorescent staining. The data were analyzed with one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test (n = 4). (c) Immunofluorescent staining at week 6 after SAON surgical treatment in SD rats (negative control group in Figure S5). Representative Western Blot images from three independent experiments for osteogenic markers (osteocalcin and active β-catenin) (d), and adipogenic markers (CEBPα and PPARγ), proliferative marker (PCNA), inflammatory marker (tyrosine-kinase transmembrane receptor for CSF1), and indicator for osteonecrosis (c-Src) (e) (n = 3 per condition; Lane 1, blank repair; Lane 2, Gel; Lane 3, icaritin+Gel; Lane 4, icaritin+MSC+Gel). Injection of Ci-I gelatin hydrogels, which were loaded with both MSCs and icaritin (“icaritin+MSC+Gel”), activated β-catenin and osteocalcin signaling but inhibited the inflammatory response and adipogenesis. The quantitative data are shown in Figure S6. (f) Sequential labeling of newly formed bone with calcein green (CG) and xylenol orange (XO) in the methyl methacrylate-embedded icaritin+MSC+Gel sample at week 3 postsurgery. OB, old bone; T, bone tunnel. (g) Representative images of CG and XO staining (n = 4 images per group) for calculating the bone formation rate. OB, old bone; T, bone tunnel. The quantitative analyses of the bone formation rate at week 3 (h) and week 6 (i) postsurgery were obtained by analyzing the images in part g. The data were analyzed with one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test (n = 4). ***P < 0.001; scale bar, 100 μm (part c).

Delivery of Icaritin by Ci-I Hydrogels Facilitates the Recruitment of Endogenous Cells To Expedite the Healing of SAON in Vivo

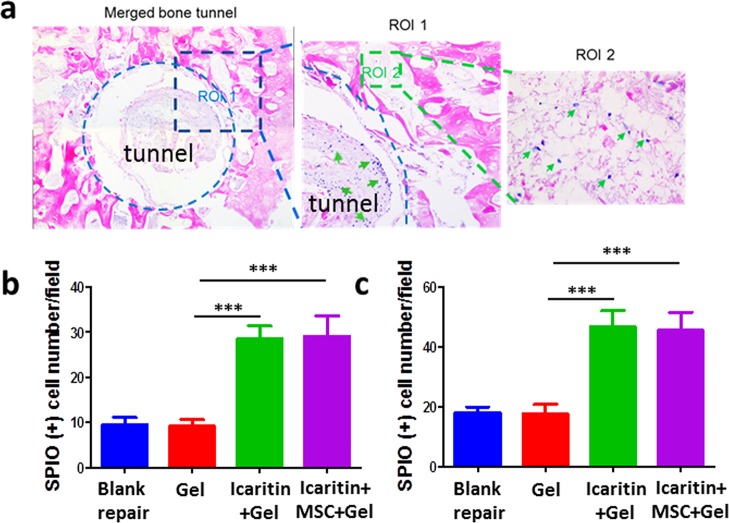

Our in vitro data have demonstrated that icaritin-laden Ci-I gelatin hydrogels can attract MSCs to infiltrate and migrate into hydrogels (Figure 2b). To evaluate the cell recruitment in vivo, immediately after the core decompression surgery and treatment with hydrogel injections in the created tunnel, we injected SPIO-labeled MSCs (1 million cells in 100 μL of media) in the ipsilateral tibia of the same limb. Six weeks postsurgery, the SPIO-labeled MSCs were hardly found within and around the tunnels with no hydrogel implantation (“Blank”) or with blank hydrogel implantation (“Gel”) (Figure 6). However, significantly more SPIO-labeled MSCs were found within and around the tunnels which were injected with hydrogels containing either icaritin alone (“icaritin+Gel”) or both MSCs and icaritin (“icaritin+MSC+Gel”) (Figure 6). This is consistent with our previous finding that icaritin can directly promote the migration of MSCs by upregulating the expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1).54 These data further demonstrated that the icaritin-laden Ci-I gelatin hydrogels can recruit endogenous MSCs from the surrounding tissues to migrate to the bone defects, thereby promoting new bone formation.

Figure 6.

(a) Prussian blue and nuclear fast red staining of the histological sections of the femoral heads treated with MSCs and icaritin-laden Ci-I hydrogels. SPIO positive cells are indicated by green arrows. SPIO positive cells within the tunnel (b) and around the tunnel (c) were counted. The data were analyzed with one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test (n = 6, ***P < 0.001).

Conclusions

Collectively, we demonstrate a unique injectable hydrogel with desirable properties including ease of preparation, unscathed mechanical properties after injection, sustained delivery of small hydrophobic molecular drugs, and injection with encapsulated cells. Furthermore, the dynamic physical cross-links in this hydrogel enable the infiltration and migration of cells from the surrounding environment to speed up the in situ bone regeneration in a SAON animal model. This injectable hydrogel can be easily customized to carry different portfolios of therapeutic drugs and cells for treating a wide array of clinical conditions via minimally invasive procedures in deep and enclosed anatomical locations.

Acknowledgments

The work described in this Article was substantially supported by Theme-based Research grant (T13-402/17-N) and General Research Fund grant (14202215) from the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, and a grant from National Natural Science Foundation of China (31570979). This work was also supported by the Health and Medical Research Fund (Ref. 03140056) from the Food and Health Bureau and an Innovation Technology Fund (TCFS, GHP/011/17SZ) in Hong Kong.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acscentsci.8b00764.

Detailed methods and additional figures including 1H NMR, rheological time sweep test, cell viability staining, negative control groups for immunofluorescent staining, and quantitative data for the Western Blot images (PDF)

Three-dimensional distribution of DAPI-stained human mesenchymal stem cell (hMSC) nuclei within the Ci-I hydrogels without icaritin encapsulation after 24 h of in vitro culture (AVI)

Three-dimensional distribution of DAPI-stained human mesenchymal stem cell (hMSC) nuclei within the Ci-I hydrogels with icaritin encapsulation after 24 h of in vitro culture (AVI)

Author Contributions

◆ Q.F. and J.X. contributed equally.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Huang Q.; Zou Y.; Arno M. C.; Chen S.; Wang T.; Gao J.; Dove A. P.; Du J. Hydrogel scaffolds for differentiation of adipose-derived stem cells. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46 (20), 6255–6275. 10.1039/C6CS00052E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv S.; Wu Y.; Cai K.; He H.; Li Y.; Lan M.; Chen X.; Cheng J.; Yin L. High Drug Loading and Sub-Quantitative Loading Efficiency of Polymeric Micelles Driven by Donor–Receptor Coordination Interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140 (4), 1235–1238. 10.1021/jacs.7b12776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillel A. T.; Unterman S.; Nahas Z.; Reid B.; Coburn J.; Axelman J.; Chae J. J.; Guo Q.; Trow R.; Thomas A. Photoactivated Composite Biomaterial for Soft Tissue Restoration in Rodents and in Humans. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011, 3 (93), 93ra67. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouwkema J.; Rivron N. C.; Van Blitterswijk C. A. Vascularization in tissue engineering. Trends Biotechnol. 2008, 26 (8), 434–441. 10.1016/j.tibtech.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speidel A. T.; Stuckey D. J.; Chow L. W.; Jackson L. H.; Noseda M.; Paiva M. A.; Schneider M. D.; Stevens M. M. Multimodal Hydrogel-Based Platform To Deliver and Monitor Cardiac Progenitor/Stem Cell Engraftment. ACS Cent. Sci. 2017, 3 (4), 338–348. 10.1021/acscentsci.7b00039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampe K. J.; Antaris A. L.; Heilshorn S. C. Design of three-dimensional engineered protein hydrogels for tailored control of neurite growth. Acta Biomater. 2013, 9 (3), 5590–5599. 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.10.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turabee M. H.; Thambi T.; Duong H. T. T.; Jeong J. H.; Lee D. S. A pH- and temperature-responsive bioresorbable injectable hydrogel based on polypeptide block copolymers for the sustained delivery of proteins in vivo. Biomater. Sci. 2018, 6 (3), 661–671. 10.1039/C7BM00980A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Acuña R.; Quirós M.; Farkas A. E.; Dedhia P. H.; Huang S.; Siuda D.; García-Hernández V.; Miller A. J.; Spence J. R.; Nusrat A. Synthetic hydrogels for human intestinal organoid generation and colonic wound repair. Nat. Cell Biol. 2017, 19 (11), 1326. 10.1038/ncb3632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha C.-W.; Park Y.-B.; Chung J.-Y.; Park Y.-G. Cartilage repair using composites of human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells and hyaluronic acid hydrogel in a minipig model. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2015, 4 (9), 1044–1051. 10.5966/sctm.2014-0264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakahata M.; Takashima Y.; Yamaguchi H.; Harada A. Redox-responsive self-healing materials formed from host–guest polymers. Nat. Commun. 2011, 2, 511. 10.1038/ncomms1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Q.; Lin S.; Zhang K.; Dong C.; Wu T.; Huang H.; Yan X.; Zhang L.; Li G.; Bian L. Sulfated hyaluronic acid hydrogels with retarded degradation and enhanced growth factor retention promote hMSC chondrogenesis and articular cartilage integrity with reduced hypertrophy. Acta Biomater. 2017, 53, 329–342. 10.1016/j.actbio.2017.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mejia Oneto J. M.; Khan I.; Seebald L.; Royzen M. In Vivo Bioorthogonal Chemistry Enables Local Hydrogel and Systemic Pro-Drug To Treat Soft Tissue Sarcoma. ACS Cent. Sci. 2016, 2 (7), 476–482. 10.1021/acscentsci.6b00150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bian L.; Hou C.; Tous E.; Rai R.; Mauck R. L.; Burdick J. A. The influence of hyaluronic acid hydrogel crosslinking density and macromolecular diffusivity on human MSC chondrogenesis and hypertrophy. Biomaterials 2013, 34 (2), 413–421. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.09.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. C.; Lin R. Z.; Qi H.; Yang Y.; Bae H.; Melero-Martin J. M.; Khademhosseini A. Functional human vascular network generated in photocrosslinkable gelatin methacrylate hydrogels. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2012, 22 (10), 2027–2039. 10.1002/adfm.201101662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelps E. A.; Enemchukwu N. O.; Fiore V. F.; Sy J. C.; Murthy N.; Sulchek T. A.; Barker T. H.; García A. J. Maleimide cross-linked bioactive peg hydrogel exhibits improved reaction kinetics and cross-linking for cell encapsulation and in situ delivery. Adv. Mater. 2012, 24 (1), 64–70. 10.1002/adma.201103574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang N.; Pereira M. J.; Lee Y.; Friehs I.; Vasilyev N. V.; Feins E. N.; Ablasser K.; O’cearbhaill E. D.; Xu C.; Fabozzo A. A blood-resistant surgical glue for minimally invasive repair of vessels and heart defects. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6 (218), 218ra6–218ra6. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Q.; Wei K.; Lin S.; Xu Z.; Sun Y.; Shi P.; Li G.; Bian L. Mechanically resilient, injectable, and bioadhesive supramolecular gelatin hydrogels crosslinked by weak host-guest interactions assist cell infiltration and in situ tissue regeneration. Biomaterials 2016, 101, 217–228. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khetan S.; Guvendiren M.; Legant W. R.; Cohen D. M.; Chen C. S.; Burdick J. A. Degradation-mediated cellular traction directs stem cell fate in covalently crosslinked three-dimensional hydrogels. Nat. Mater. 2013, 12 (5), 458. 10.1038/nmat3586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke D. E.; Parmenter C. D. J.; Scherman O. A. Tunable pentapeptide self-assembled β-sheet hydrogels. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57 (26), 7709–7713. 10.1002/anie.201801001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou J.; Liu F.; Lindsay C. D.; Chaudhuri O.; Heilshorn S. C.; Xia Y. Dynamic Hyaluronan Hydrogels with Temporally Modulated High Injectability and Stability Using a Biocompatible Catalyst. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30 (22), 1705215. 10.1002/adma.201705215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Q.; Wei K.; Zhang K.; Yang B.; Tian F.; Wang G.; Bian L. One-pot solvent exchange preparation of non-swellable, thermoplastic, stretchable and adhesive supramolecular hydrogels based on dual synergistic physical crosslinking. NPG Asia Mater. 2018, 10 (1), e455. 10.1038/am.2017.208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bai S.; Nguyen T. L.; Mulvaney P.; Wang D. Using hydrogels to accommodate hydrophobic nanoparticles in aqueous media via solvent exchange. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22 (30), 3247–3250. 10.1002/adma.201000336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y.; Wang X.; Yang F.; Wang L.; Wu D. Highly Elastic and Ultratough Hybrid Ionic–Covalent Hydrogels with Tunable Structures and Mechanics. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1707071. 10.1002/adma.201707071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takashima Y.; Harada A. Stimuli-responsive polymeric materials functioning via host–guest interactions. J. Inclusion Phenom. Macrocyclic Chem. 2017, 88 (3–4), 85–104. 10.1007/s10847-017-0714-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H.; Xu G.; Li J.; Zeng S.; Zhang X.; Zheng Z.; Ding X.; Chen W.; Wang Q.; Zhang W. Preparation and self-healing behaviors of poly (acrylic acid)/cerium ions double network hydrogels. Macromol. Res. 2015, 23 (12), 1098–1102. 10.1007/s13233-015-3145-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J.-Y.; Zhao X.; Illeperuma W. R.; Chaudhuri O.; Oh K. H.; Mooney D. J.; Vlassak J. J.; Suo Z. Highly stretchable and tough hydrogels. Nature 2012, 489 (7414), 133. 10.1038/nature11409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q.; Mynar J. L.; Yoshida M.; Lee E.; Lee M.; Okuro K.; Kinbara K.; Aida T. High-water-content mouldable hydrogels by mixing clay and a dendritic molecular binder. Nature 2010, 463 (7279), 339. 10.1038/nature08693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Li Y.; Liu W. Dipole–Dipole and H-Bonding Interactions Significantly Enhance the Multifaceted Mechanical Properties of Thermoresponsive Shape Memory Hydrogels. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2015, 25 (3), 471–480. 10.1002/adfm.201401989. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tycko R.; Blanco F. J.; Ishii Y. Alignment of biopolymers in strained gels: a new way to create detectable dipole– dipole couplings in high-resolution biomolecular NMR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122 (38), 9340–9341. 10.1021/ja002133q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.; Tan C. S. Y.; Yu Z.; Lan Y.; Abell C.; Scherman O. A. Biomimetic Supramolecular Polymer Networks Exhibiting both Toughness and Self-Recovery. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29 (10), 1604951. 10.1002/adma.201604951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamae K.; Nakahata M.; Takashima Y.; Harada A. Self-Healing, Expansion–Contraction, and Shape-Memory Properties of a Preorganized Supramolecular Hydrogel through Host–Guest Interactions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54 (31), 8984–8987. 10.1002/anie.201502957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Z.; Liu J.; Tan C. S. Y.; Scherman O. A.; Abell C. Supramolecular Nested Microbeads as Building Blocks for Macroscopic Self-Healing Scaffolds. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57 (12), 3079–3083. 10.1002/anie.201711522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webber M. J.; Appel E. A.; Meijer E.; Langer R. Supramolecular biomaterials. Nat. Mater. 2016, 15 (1), 13. 10.1038/nmat4474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei K.; Chen X.; Li R.; Feng Q.; Bian L. Multivalent Host–Guest Hydrogels as Fatigue-Resistant 3D Matrix for Excessive Mechanical Stimulation of Encapsulated Cells. Chem. Mater. 2017, 29 (20), 8604–8610. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.7b02196. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wei K.; Zhu M.; Sun Y.; Xu J.; Feng Q.; Lin S.; Wu T.; Xu J.; Tian F.; Xia J. Robust biopolymeric supramolecular “host– guest macromer” hydrogels reinforced by in situ formed multivalent nanoclusters for cartilage regeneration. Macromolecules 2016, 49 (3), 866–875. 10.1021/acs.macromol.5b02527. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. S.; Khademhosseini A. Advances in engineering hydrogels. Science 2017, 356 (6337), eaaf3627. 10.1126/science.aaf3627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madl C. M.; Heilshorn S. C. Bioorthogonal Strategies for Engineering Extracellular Matrices. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28 (11), 1706046. 10.1002/adfm.201706046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madl C. M.; LeSavage B. L.; Dewi R. E.; Dinh C. B.; Stowers R. S.; Khariton M.; Lampe K. J.; Nguyen D.; Chaudhuri O.; Enejder A. Maintenance of neural progenitor cell stemness in 3D hydrogels requires matrix remodelling. Nat. Mater. 2017, 16 (12), 1233. 10.1038/nmat5020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng T. C.; Tao L.; Hsieh F. Y.; Wei Y.; Chiu I. M.; Hsu S. h. An injectable, self-healing hydrogel to repair the central nervous system. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27 (23), 3518–3524. 10.1002/adma.201500762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L.; Yan B.; Yang J.; Chen L.; Zeng H. Novel Mussel-Inspired Injectable Self-Healing Hydrogel with Anti-Biofouling Property. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27 (7), 1294–1299. 10.1002/adma.201405166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mealy J. E.; Rodell C. B.; Burdick J. A. Sustained small molecule delivery from injectable hyaluronic acid hydrogels through host–guest mediated retention. J. Mater. Chem. B 2015, 3 (40), 8010–8019. 10.1039/C5TB00981B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell B. P.; Lobb D.; Charati M. B.; Dorsey S. M.; Wade R. J.; Zellars K. N.; Doviak H.; Pettaway S.; Logdon C. B.; Shuman J. A. Injectable and bioresponsive hydrogels for on-demand matrix metalloproteinase inhibition. Nat. Mater. 2014, 13 (6), 653. 10.1038/nmat3922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodell C. B.; MacArthur J. W.; Dorsey S. M.; Wade R. J.; Wang L. L.; Woo Y. J.; Burdick J. A. Shear-thinning supramolecular hydrogels with secondary autonomous covalent crosslinking to modulate viscoelastic properties in vivo. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2015, 25 (4), 636–644. 10.1002/adfm.201403550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai L.; Dewi R. E.; Goldstone A. B.; Cohen J. E.; Steele A. N.; Woo Y. J.; Heilshorn S. C. Regulating stem cell secretome using injectable hydrogels with in situ network formation. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2016, 5 (21), 2758–2764. 10.1002/adhm.201600497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assoulinedayan Y.; Chang C.; Greenspan A.; Shoenfeld Y.; Gershwin M. E. Pathogenesis and natural history of osteonecrosis. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2002, 32 (2), 94–124. 10.1053/sarh.2002.33724b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan M. H.; Chan P. K.; Griffith J. F.; Chan I. H.; Lit L. C.; Wong C.; Antonio G. E.; Liu E. Y.; Hui D. S.; Suen M. W. Steroid-induced osteonecrosis in severe acute respiratory syndrome: a retrospective analysis of biochemical markers of bone metabolism and corticosteroid therapy. Pathology 2006, 38 (3), 229–235. 10.1080/00313020600696231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeuchi K.; Hasegawa Y.; Seki T.; Takegami Y.; Amano T.; Ishiguro N. Epidemiology of nontraumatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head in Japan. Mod. Rheumatol. 2015, 25 (2), 278–281. 10.3109/14397595.2014.932038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mont M. A.; Jones L. C.; Hungerford D. S. Nontraumatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head: ten years later. JBJS 2006, 88 (5), 1117–1132. 10.2106/JBJS.E.01041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell C.; Chang C.; Naguwa S. M.; Cheema G.; Gershwin M. E. Steroid induced osteonecrosis: an analysis of steroid dosing risk. Autoimmun. Rev. 2010, 9 (11), 721–743. 10.1016/j.autrev.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao H.; Guan H.; Lai Y.; Qin L.; Wang X. Review of various treatment options and potential therapies for osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Journal of Orthopaedic Translation 2016, 4, 57–70. 10.1016/j.jot.2015.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie X.-H.; Wang X.-L.; Yang H.-L.; Zhao D.-W.; Qin L. Steroid-associated osteonecrosis: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, animal model, prevention, and potential treatments (an overview). Journal of Orthopaedic Translation 2015, 3 (2), 58–70. 10.1016/j.jot.2014.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L.-Z.; Wang J.-L.; Kong L.; Huang L.; Tian L.; Pang Q.-Q.; Wang X.-L.; Qin L. Steroid-associated osteonecrosis animal model in rats. Journal of Orthopaedic Translation 2018, 13, 13–24. 10.1016/j.jot.2018.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. L.; Xie X. H.; Zhang G.; Chen S. H.; Yao D.; He K.; Wang X. H.; Yao X. S.; Leng Y.; Fung K. P. Exogenous phytoestrogenic molecule icaritin incorporated into a porous scaffold for enhancing bone defect repair. J. Orthop. Res. 2013, 31 (1), 164–172. 10.1002/jor.22188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin L.; Yao D.; Zheng L.; Liu W.-C.; Liu Z.; Lei M.; Huang L.; Xie X.; Wang X.; Chen Y. Phytomolecule icaritin incorporated PLGA/TCP scaffold for steroid-associated osteonecrosis: Proof-of-concept for prevention of hip joint collapse in bipedal emus and mechanistic study in quadrupedal rabbits. Biomaterials 2015, 59, 125–143. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.04.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L. Z.; Cao H. J.; Chen S. H.; Tang T.; Fu W. M.; Huang L.; Chow D. H.; Wang Y. X.; Griffith J. F.; He W.; et al. Blockage of Src by Specific siRNA as a Novel Therapeutic Strategy to Prevent Destructive Repair in Steroid-Associated Osteonecrosis in Rabbits. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2015, 30 (11), 2044–2057. 10.1002/jbmr.2542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein R. S. Clinical practice. Glucocorticoid-induced bone disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365 (1), 62–70. 10.1056/NEJMcp1012926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X.; Lang Q.; Yildirimer L.; Lin Z. Y.; Cui W.; Annabi N.; Ng K. W.; Dokmeci M. R.; Ghaemmaghami A. M.; Khademhosseini A. Photocrosslinkable gelatin hydrogel for epidermal tissue engineering. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2016, 5 (1), 108–118. 10.1002/adhm.201500005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franses J. W.; Baker A. B.; Chitalia V. C.; Edelman E. R. Stromal endothelial cells directly influence cancer progression. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011, 3 (66), 66ra5–66ra5. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S.; Pati F.; Choi Y.-J.; Rijal G.; Shim J.-H.; Kim S. W.; Ray A. R.; Cho D.-W.; Ghosh S. Bioprintable, cell-laden silk fibroin–gelatin hydrogel supporting multilineage differentiation of stem cells for fabrication of three-dimensional tissue constructs. Acta Biomater. 2015, 11, 233–246. 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshy S. T.; Desai R. M.; Joly P.; Li J.; Bagrodia R. K.; Lewin S. A.; Joshi N. S.; Mooney D. J. Click-Crosslinked Injectable Gelatin Hydrogels. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2016, 5 (5), 541–547. 10.1002/adhm.201500757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahadik B. P.; Haba S. P.; Skertich L. J.; Harley B. A. The use of covalently immobilized stem cell factor to selectively affect hematopoietic stem cell activity within a gelatin hydrogel. Biomaterials 2015, 67, 297–307. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.07.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo Y.; Liu X.; Wei D.; Sun J.; Xiao W.; Zhao H.; Guo L.; Wei Q.; Fan H.; Zhang X. Photo-cross-linkable methacrylated gelatin and hydroxyapatite hybrid hydrogel for modularly engineering biomimetic osteon. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7 (19), 10386–10394. 10.1021/acsami.5b01433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikkhah M.; Eshak N.; Zorlutuna P.; Annabi N.; Castello M.; Kim K.; Dolatshahi-Pirouz A.; Edalat F.; Bae H.; Yang Y. Directed endothelial cell morphogenesis in micropatterned gelatin methacrylate hydrogels. Biomaterials 2012, 33 (35), 9009–9018. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.08.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue K.; Trujillo-de Santiago G.; Alvarez M. M.; Tamayol A.; Annabi N.; Khademhosseini A. Synthesis, properties, and biomedical applications of gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA) hydrogels. Biomaterials 2015, 73, 254–271. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.08.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguado B. A.; Mulyasasmita W.; Su J.; Lampe K. J.; Heilshorn S. C. Improving viability of stem cells during syringe needle flow through the design of hydrogel cell carriers. Tissue Eng., Part A 2012, 18 (7–8), 806–815. 10.1089/ten.tea.2011.0391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H.; Heilshorn S. C. Adaptable hydrogel networks with reversible linkages for tissue engineering. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27 (25), 3717–3736. 10.1002/adma.201501558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parisi-Amon A.; Mylyasasmita W.; Chung C.; Heilshorn S. C. Protein-engineered injectable hydrogel to improve retention of transplanted adipose-derived stem cells. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2013, 2 (3), 428–432. 10.1002/adhm.201200293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai L.; Dewi R. E.; Heilshorn S. C. Injectable hydrogels with in situ double network formation enhance retention of transplanted stem cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2015, 25 (9), 1344–1351. 10.1002/adfm.201403631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Challa R.; Ahuja A.; Ali J.; Khar R. Cyclodextrins in drug delivery: an updated review. AAPS PharmSciTech 2005, 6 (2), E329–E357. 10.1208/pt060243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uekama K.; Hirayama F.; Irie T. Cyclodextrin drug carrier systems. Chem. Rev. 1998, 98 (5), 2045–2076. 10.1021/cr970025p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uekama K.; Otagiri M. Cyclodextrins in drug carrier systems. Crit. Rev. Ther. Drug Carrier Syst. 1987, 3 (1), 1–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai Y.; Cao H.; Wang X.; Chen S.; Zhang M.; Wang N.; Yao Z.; Dai Y.; Xie X.; Zhang P.; et al. Porous composite scaffold incorporating osteogenic phytomolecule icariin for promoting skeletal regeneration in challenging osteonecrotic bone in rabbits. Biomaterials 2018, 153, 1–13. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark Fisher D.; Min-Leong Wong J.; Crowley C.; S Khan W. Preclinical and clinical studies on the use of growth factors for bone repair: a systematic review. Curr. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2013, 8 (3), 260–268. 10.2174/1574888X11308030011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin L.; Li Y.-b.; Wang Y.-s. Dexamethasone-induced adipogenesis in primary marrow stromal cell cultures: mechanism of steroid-induced osteonecrosis. Chin. Med. J. (Engl.) 2006, 119 (7), 581–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J.; Li Z.; Hou Y.; Fang W. Potential mechanisms underlying the Runx2 induced osteogenesis of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2015, 7 (12), 2527–2535. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doloff J. C.; Veiseh O.; Vegas A. J.; Tam H. H.; Farah S.; Ma M.; Li J.; Bader A.; Chiu A.; Sadraei A. Colony stimulating factor-1 receptor is a central component of the foreign body response to biomaterial implants in rodents and non-human primates. Nat. Mater. 2017, 16 (6), 671–680. 10.1038/nmat4866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.; Hu Y.; He L.; Wang S.; Zhou H.; Liu S. Icaritin inhibits T cell activation and prolongs skin allograft survival in mice. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2012, 13 (1), 1–7. 10.1016/j.intimp.2012.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.