Key Points

Question

What is the optimal diagnostic strategy for bullous and nonbullous variants of pemphigoid?

Findings

In this paired, multivariable, diagnostic accuracy study of 1125 patients with suspected bullous or nonbullous pemphigoid, 1 in 5 patients with a pemphigoid diagnosis had no skin blistering. Pemphigoid diagnosis could be made with positive direct immunofluorescence microscopy on a skin biopsy specimen and/or indirect immunofluorescence on human salt-split skin substrate in serum; results of the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for BP180 NC16A did not have added diagnostic value.

Meaning

Performing both direct immunofluorescence and indirect immunofluorescence on salt-split skin tests is recommended for pemphigoid diagnosis, along with BP180 NC16A enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay as an add-on test for disease activity monitoring; the proposed diagnostic criteria allow the diagnosis of all pemphigoid variants.

Abstract

Importance

A substantial number of patients with bullous pemphigoid do not develop skin blisters and may not have received the correct diagnosis. Diagnostic criteria and an optimal diagnostic strategy are needed for early recognition and trials.

Objectives

To assess the minimal requirements for diagnosis of bullous and nonbullous forms of pemphigoid and to evaluate the optimal diagnostic strategy.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This paired, multivariable, diagnostic accuracy study analyzed data from 1125 consecutive patients with suspected pemphigoid who were referred to the Groningen Center for Blistering Diseases from secondary and tertiary care hospitals throughout the Netherlands. Eligible participants were patients with paired data on at least (1) a skin biopsy specimen for the direct immunofluorescence (DIF) microscopy test; (2) indirect immunofluorescence on a human salt-split skin substrate (IIF SSS) test; and (3) 1 or more routine immunoserologic tests administered between January 1, 2002, and May 1, 2015. Samples were taken from patients at the time of first diagnosis, before introduction of immunosuppressive therapy, and within an inclusion window of a maximum of 4 weeks. Data analysis was conducted from October 1, 2015, to December 1, 2017.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Pairwise DIF, IIF SSS, IIF on monkey esophagus, BP180 and BP230 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays, and immunoblot for BP180 and BP230 tests were performed. The results were reported in accordance with 2015 version of the Standards for Reporting Diagnostic Accuracy.

Results

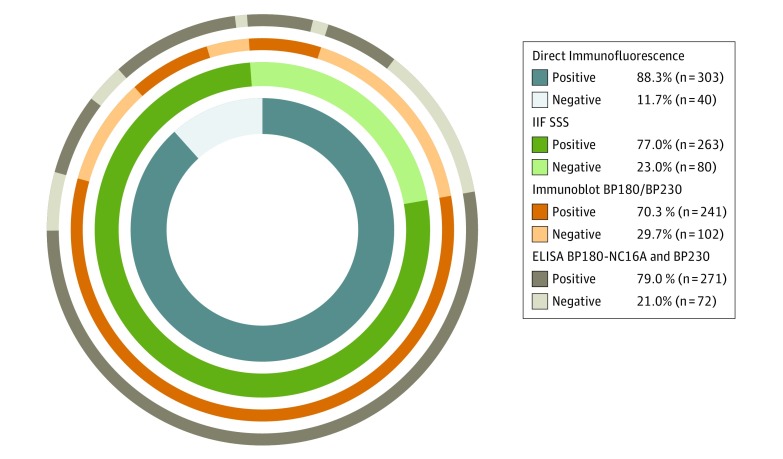

Of the 1125 patients analyzed, 653 (58.0%) were women and 472 (42.0%) were men, with a mean (SD) age of 63.2 (19.9) years. In total, 343 participants received a pemphigoid diagnosis, with 782 controls. Of the 343 patients, 74 (21.6%, or 1 in 5) presented with nonbullous pemphigoid. The DIF microscopy was the most sensitive diagnostic test (88.3% [n = 303]; 95% CI, 84.5%-91.3%), whereas IIF SSS was less sensitive (77.0% [n = 263]; 95% CI, 72.2%-81.1%) but was highly specific (99.9%; 95% CI, 99.3%-100%) and complemented most cases with negative DIF findings. Results of the BP180 NC16A enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay did not add diagnostic value for initial diagnosis in multivariable logistic regression analysis of combined tests. These findings lead to the proposed minimal criteria for diagnosing pemphigoid: (1) pruritus and/or predominant cutaneous blisters, (2) linear IgG and/or C3c deposits (in an n-serrated pattern) by DIF on a skin biopsy specimen, and (3) positive epidermal side staining of IgG by IIF SSS on a serum sample; this proposal extends bullous pemphigoid with the unrecognized nonbullous form.

Conclusions and Relevance

Both DIF and IIF SSS tests should be performed for diagnosis of the bullous and nonbullous variants of pemphigoid, and the BP180 NC16A enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay is recommended as an add-on test for disease activity monitoring.

This study analyzes the direct immunofluorescence and serologic data from 1125 consecutive patients for diagnosing pemphigoid, a cutaneous autoimmune disease that primarily affects older people.

Introduction

More than 20% of patients with bullous pemphigoid do not present with typical skin blistering, but with a pruritic nonbullous variant consisting of erythematous urticarial plaques, eczematous lesions, papules and nodules, or only excoriations.1,2,3 These patients with nonbullous pemphigoid may often have a misdiagnosis or be overlooked with a prolonged physician delay, especially in cases in which blisters never develop.3,4 Bullous pemphigoid is the most frequent subepidermal autoimmune bullous disease (sAIBD) and mainly affects older people.1,5 It is characterized by the presence of circulating IgG autoantibodies targeting the structural proteins BP180 and BP230 of the epidermal basement membrane zone.5 Annual incidence of bullous pemphigoid in Europe has increased substantially in the past decades, which might be attributed to an aging population, the availability of better diagnostic tests, and the recognition of patients with atypical clinical features.1,6

Minimal diagnostic criteria for pemphigoid are needed but have not yet been established.4,7 Currently, the diagnosis is based on the typical presentation using combined clinical criteria8,9 to separate it from other pemphigoid diseases (such as mucous membrane pemphigoid, linear IgA disease, and epidermolysis bullosa acquisita), the histopathologic features of a subepidermal blister, and the detection of autoantibodies in a skin biopsy specimen by direct immunofluorescence (DIF) microscopy and in a blood sample by various immunoserologic tests.10,11,12 The 2015 European Dermatology Forum consensus recommendations11 require a positive DIF biopsy result for diagnosis, whereas the 2015 German guideline also allows diagnosis using various combinations of serologic tests.12 Studies suggest high diagnostic accuracies of commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits,13,14 but methodologic flaws may have led to an overestimation of the diagnostic accuracy in the intended population.

We evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of the DIF test on a skin biopsy specimen and various serologic tests in a paired study design involving a large cohort with suspected bullous or nonbullous pemphigoid. We then assessed the optimal diagnostic strategy by comparing the additional diagnostic value of combined diagnostic tests in multivariable logistic regression modeling, and we evaluated which tests should be performed for diagnosis at least (minimal requirements). Informed by these evaluations, we propose minimal diagnostic criteria for pemphigoid that support early recognition of this common cutaneous autoimmune disease.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

This single-center retrospective study was performed at the Groningen Center for Blistering Diseases, the national referral center for autoimmune bullous diseases in Groningen, the Netherlands. The study population consisted of consecutive patients with suspected pemphigoid from secondary and tertiary care hospitals throughout the Netherlands, including older people who had severe or refractory itch with or without skin blistering. Eligible participants were patients with paired data on at least (1) a skin biopsy specimen for the DIF test; (2) indirect immunofluorescence on a human salt-split skin (IIF SSS) substrate test; and (3) 1 or more routine immunoserologic tests administered between January 1, 2002, and May 1, 2015. Samples were taken at the time of first diagnosis, before introduction of immunosuppressive therapy, and within an inclusion window of a maximum of 4 weeks. This study reports diagnostic tests in accordance with the Standards for Reporting Diagnostic Accuracy; see the eAppendix in the Supplement for a list of essential items for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies.15 According to national regulations in the Netherlands,16 this type of retrospective noninterventional study with leftover materials for diagnostic purposes does not require approval from the local medical ethical committee.

Reference Standard and Index Tests

No consensus reference standard for the diagnosis of pemphigoid was established. We used as a composite reference standard the criteria for diagnosis of the 2015 German S2k Guideline for diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid.12 Compatible clinical presentation of pemphigoid was defined as the presence of pruritus and predominant tense skin blisters or nonbullous skin morphologic features (not further specified). Results of direct immunofluorescence on a skin biopsy specimen were considered positive when linear or linear n-serrated–pattern deposits of IgG and/or C3c along the epidermal basement membrane zone were observed.11,17 The finding of indirect immunofluorescence on a human salt-split skin substrate (IIF SSS) test was considered positive when epidermal side staining of IgG was observed.11 The clinical diagnosis of pemphigoid was made in the following cases: (1) compatible clinical presentation and a positive DIF finding, (2) compatible clinical presentation and a positive DIF finding as well as a positive IIF SSS result, (3) compatible clinical presentation and a positive IIF SSS finding as well as positivity in at least 1 other immunoserologic test (eg, immunoblot with reactivity to BP180 or BP230, IIF on monkey esophagus [ME] substrate, or BP180 or BP230 ELISA), and (4) compatible clinical presentation of tense blisters and a compatible histopathologic finding of subepidermal blister as well as a positive BP180 ELISA result and positivity in at least 1 other immunoserologic test (eg, immunoblot with reactivity to BP180 or BP230, IIF ME substrate, or BP230 ELISA).

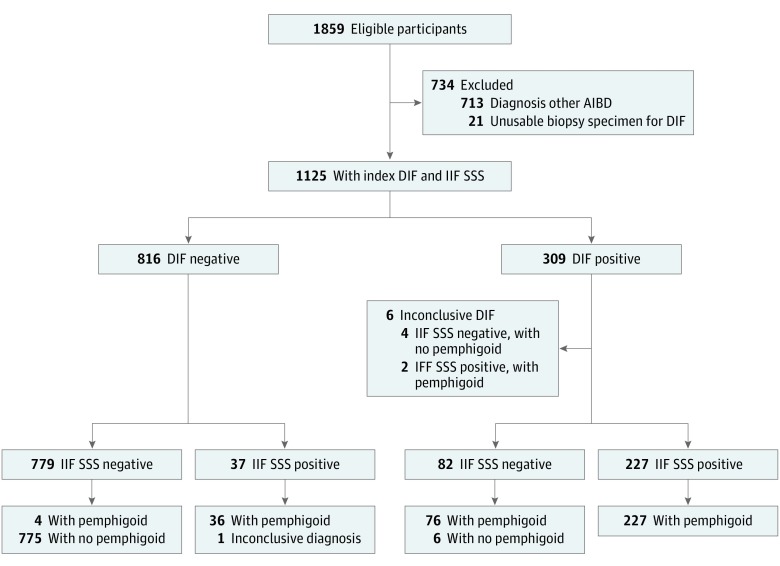

Clinical features and test outcomes of cases with indeterminate or a single positive index test result were discussed among us, specifically by physicians (J.M.M. and M.F.J.), a pathologist (G.D.), and a biochemist (H.P.), to confirm a reject diagnosis of pemphigoid. Histopathologic data were not routinely analyzed in the study because histopathologic study is often nonspecific in nonbullous pemphigoid, does not enable differentiation of subtypes of pemphigoid diseases, and was not available in all cases.11 Excluded were participants with suspected mucous membrane pemphigoid as well as participants with a diagnosis of other autoimmune (bullous) diseases based on DIF findings and immunoserology results, including a linear u-serrated pattern (epidermolysis bullosa acquisita/bullous systemic lupus erythematosus), solely IgA depositions, or with IgG against autoantigens other than BP180 or BP230 (Figure 1). Diagnostic tests and assessments of the reference standard were separately performed.

Figure 1. Study Flow Diagram .

Classification based on the reference standard. Based on the index tests direct immunofluorescence (DIF) microscopy and indirect immunofluorescence on human salt-split skin (IIF SSS) substrate, eligible participants with other diagnoses were excluded. AIBD indicates autoimmune bullous disease.

Biopsy specimens for DIF were transported and stored mainly in saline solution (0.9% NaCl, overnight), liquid nitrogen, or Michel medium.17,18 Biopsy sites were defined in advance as (1) perilesional skin: erythematous nonbullous skin within 2 cm from a lesion; (2) lesional skin: bullous or nonbullous lesion except erosions; and (3) healthy skin: normal-appearing noninflamed skin from the inner aspect of upper arm. Serration pattern analysis was assessed by routine DIF from 2009 onward using either a microscope with a 40× dry objective and 10× ocular lens, with a total magnification of ×400 (Leica DM2000 or LEICA DMRA; Leica Microsystems).17,19 The IIF SSS test was performed with a standard dilution of 1:8 (as described in the eMethods in the Supplement) on human substrate (from donated normal human skin tissue freshly obtained from routine reduction mammoplasty and abdominoplasty after signed informed consent) and validated with positive and negative controls.19 The routine multistep immunoserologic test procedure included IIF on ME substrate, immunoblot with keratinocyte extract tested for IgG and IgA autoantibodies against BP180 and BP230,20 and commercially available BP180 NC16A (from 2007 onward) and BP230 (from 2009 onward) ELISA kits (Medical and Biological Laboratories Co) used according to the manufacturer’s protocol and with a positivity cutoff value of 9 U/mL or greater. Missing ELISA tests of patients with pemphigoid (n = 201) were performed post hoc.

Statistical Analyses

Data analysis was conducted from October 1, 2015, to December 1, 2017. We calculated diagnostic accuracy with the composite reference standard, including sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values, positive and negative likelihood ratios, and diagnostic odds ratio (OR) according to standardized formulas and with 95% CIs. Sensitivities and specificities of paired diagnostic tests were compared using the McNemar test. The Mann-Whitney test, χ2 test, or Fisher exact test was used to compare medians and proportions. Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis was used to determine the optimal cutoff value of continuous variables of autoantibody titer of BP180 NC16A and BP230 ELISAs by calculating maximum Youden J index values. With multivariable logistic regression modeling, we evaluated the additional diagnostic value of combined diagnostic tests (DIF, IIF SSS, and BP180 NC16A ELISA) for the initial diagnosis of bullous and nonbullous pemphigoid and included clinical variables (age, sex, pruritus, and blisters) with a backward selection procedure (based on P < .20). Substantial additional value of a test was indicated when 95% CIs of areas under the curves did not overlap. Multiple imputation was used for random missing data of BP180 NC16A ELISA in 20% of nonpemphigoid controls, with no substantial differences between imputed and nonimputed groups. Two-sided P = .05 values were used to indicate statistical significance. We used SPSS Statistics, version 22 (IBM) for all analyses.

Results

From January 1, 2002, to May 1, 2015, we retrospectively analyzed data from 1125 patients with suspected bullous or nonbullous pemphigoid (Figure 1). Of the 1125 patients, 653 (58.0%) were women and 472 (42.0%) were men, with a mean (SD) age of 63.2 (19.9) years. Eventually, 343 participants (30.5%; mean [SD] age, 71.8 [7.4] years) received a pemphigoid diagnosis, compared with 782 controls (69.5%; mean [SD] age, 59.5 [19.7] years; P < .001). Of the 343 patients with a pemphigoid diagnosis, 74 (21.6%, or 1 in 5) presented with nonbullous pemphigoid. Table 1 summarizes the diagnostic accuracy of the DIF and immunoserologic tests.

Table 1. Diagnostic Performance of Laboratory Tests in Study Participants With Suspected Pemphigoid.

| Test | No. (With Pemphigoid/Controls) | % (95% CI) | Likelihood Ratio (95% CI) | Diagnostic OR (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Positive | Negative | |||

| Diagnostic Test | ||||||||

| DIF | 1125 (343/782) |

88.3 (84.5-91.3) |

99.2 (98.3-99.7) |

98.1 (95.8-99.1) |

95.1 (93.4-96.4) |

115.1 (51.8-255.7) |

0.1 (0.1-0.2) |

979.7 (411.1-2334.5) |

| IIF SSS | 1125 (343/782) |

77.0 (72.2-81.1) |

99.9 (99.3-100.0) |

99.6 (97.9-99.9) |

90.8 (88.7-92.6) |

601.9 (84.8-4271.3) |

0.2 (0.2-0.3) |

2609.9 (361.3-18 851.9) |

| IIF ME | 1077 (343/734) |

57.1 (51.9-62.3) |

98.8 (97.7-99.4) |

95.6 (91.7-97.7) |

83.1 (80.5-85.5) |

46.6 (24.2-89.8) |

0.4 (0.4-0.5) |

107.4 (53.8-214.4) |

| Immunoblot | 1093 (343/750) |

70.3 (65.2-74.9) |

94.7 (92.8-96.1) |

85.8 (81.2-89.4) |

87.4 (85.0-89.5) |

13.2 (9.7-18.0) |

0.3 (0.3-0.4) |

41.9 (28.3-62.2) |

| ELISA | ||||||||

| BP180 NC16A | 904 (343/561) |

70.0 (64.9-74.6) |

89.8 (87.1-92.1) |

80.8 (76.0-84.9) |

83.0 (79.8-85.8) |

6.9 (5.3-8.9) |

0.3 (0.3-0.4) |

20.6 (14.4-29.5) |

| BP230 | 774 (343/431) |

44.6 (39.9-49.9) |

92.8 (90.0-94.9) |

83.2 (77.1-87.9) |

67.8 (63.9-71.4) |

6.2 (4.3-8.9) |

0.6 (0.5-0.7) |

10.4 (6.8-15.9) |

| Combined Tests | ||||||||

| DIF + IIF SSS | 1125 (343/782) |

98.8 (97.0-99.7) |

99.1 (98.2-99.6) |

98.0 (95.9-99.0) |

99.5 (98.7-99.8) |

110.4 (52.8-230.9) |

0.01 (0.00-0.03) |

9838.0 (2728.6-32 265.9) |

| Bullous | 456 (239/217) |

98.3 (95.8-99.5) |

99.5 (97.5-99.9) |

99.6 (97.1-99.9) |

98.2 (95.3-99.3) |

213.4 (30.2-1508.0) |

0.02 (0.01-0.04) |

12 690.0 (1407.3-114 426.8) |

| Nonbullous | 600 (74/526) |

100.0 (95.1-100.0) |

98.9 (97.5-99.6) |

92.5 (84.8-96.5) |

100.0 (100.0-100.0) |

87.7 (39.6-194.3) |

0.00 (0.00 to ∞) |

11 931.5 (665.3-213 983.8) |

| DIF + ELISA BP180 NC16A | 904 (343/561) |

94.8 (91.8-96.9) |

88.8 (85.9-91.3) |

83.8 (80.3-86.7) |

96.5 (94.6-97.8) |

8.4 (6.7-10.7) |

0.06 (0.04-0.09) |

142.7 (83.0-245.4) |

| Bullous | 388 (239/149) |

96.7 (93.5-98.5) |

92.6 (87.2-96.3) |

95.5 (92.2-97.4) |

94.5 (89.7-97.2) |

13.1 (7.4-23.1) |

0.04 (0.02-0.07) |

362.3 (142.2-922.6) |

| Nonbullous | 460 (74/386) |

86.5 (76.6-93.3) |

87.3 (83.6-90.5) |

56.6 (49.8-63.3) |

97.1 (95.0-98.4) |

6.8 (5.2-9.0) |

0.15 (0.09-0.28) |

44.0 (21.2-91.4) |

Abbreviations: DIF, direct immunofluorescence microscopy; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; IIF, indirect immunofluorescence; ME, monkey esophagus; NPV, negative predictive value; OR, odds ratio; PPV, positive predictive value; SSS, salt-split skin.

Direct Immunofluorescence

The sensitivity of the index DIF test on a skin biopsy specimen (n = 303) was 88.3% (95% CI, 84.5%-91.3%), and the specificity was 99.2% (95% CI, 98.3%-99.7%). Solitary positive or inconclusive DIF findings were classified as false-positive in 6 participants (0.5%) in whom diagnosis of pemphigoid could not be confirmed, including chronic ulcers and a case of vasculitis. Twenty-one biopsy specimens for DIF contained artifacts with uninterpretable results and were excluded. Comparison of the biopsy sites for DIF of 1482 skin biopsy specimens showed that DIF on perilesional skin was most sensitive (90.4%; 95% CI, 85.7%-93.9%) and was superior to healthy skin (80.7%; 95% CI, 73.5%-86.5%; P = .005) or lesional skin (76.2%; 95% CI, 65.7%-84.8%; P = .002) (Table 2). In the subgroup of participants without skin blisters (n = 788), DIF had a lower sensitivity of 81.1% (95% CI, 70.0%-88.9%), and no statistically significant differences were seen between biopsy sites (Table 2). In the 343 patients with pemphigoid, DIF detected immunodepositions of IgG in 277 biopsy specimens (91.4%), C3c in 223 (73.6%), and IgA in 83 (27.4%). In addition, DIF detected solely IgG deposition in 60 specimens (19.8%), combined presence of IgG and C3c in 135 specimens (44.6%), IgG and IgA in 20 specimens (6.6%), and combined IgG, C3c, and IgA in 62 specimens (20.5%). The DIF serration pattern analysis was routinely assessed in 728 consecutive cases from 2009 onward. The distinctive linear n-serrated pattern was observed in 138 of 181 cases (76.0%) with positive DIF, and the serration pattern was undetermined in the remaining cases (43 [24%]). No false-positive n-serrated patterns were observed.

Table 2. Diagnostic Performance of Direct Immunofluorescence for Bullous and Nonbullous Pemphigoid, by Biopsy Sitea.

| Biopsy Site | No. | % (95% CI) | Likelihood Ratio (95% CI) | Diagnostic OR (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Positive | Negative | |||

| Total Group | ||||||||

| Healthy skin | 480 | 80.7 (73.5-86.5) |

99.1 (97.3-99.8) |

97.7 (93.1-99.2) |

91.5 (88.6-93.7) |

87.4 (28.3-270.2) |

0.2 (0.1-0.3) |

447.2 (134.1-1491.8) |

| Perilesional skin | 629 | 90.4 (85.7-93.9) |

99.8 (98.7-100.0) |

99.5 (96.5-99.9) |

95.1 (92.9-96.7) |

371.4 (52.4-2631.7) |

0.1 (0.1-0.2) |

3846.2 (513.7-28 800.4) |

| Lesional skin | 373 | 76.2 (65.7-84.8) |

99.7 (98.1-100.0) |

98.5 (90.0-99.8) |

93.5 (90.8-95.5) |

220.2 (31.0-1563.6) |

0.2 (0.1-0.4) |

921.6 (121.5-6993.2) |

| Participants Without Skin Blisters | ||||||||

| Healthy skin | 253 | 74.5 (59.7-86.1) |

99.0 (96.5-99.9) |

94.6 (81.4-98.6) |

94.4 (91.3-96.5) |

76.7 (19.1-307.7) |

0.3 (0.2-0.4) |

297.5 (63.8-1386.8) |

| Perilesional skin | 281 | 78.1 (62.4-89.4) |

99.6 (97.7-100.0) |

97.0 (81.8-99.6) |

96.4 (93.7-97.9) |

187.3 (26.3-1333.3) |

0.2 (0.1-0.4) |

849.7 (104.2-6930.5) |

| Lesional skin | 254 | 68.4 (51.4-82.5) |

99.5 (97.5-100.0) |

96.3 (78.4-99.5) |

94.7 (91.8-96.6) |

147.8 (20.7-1057.0) |

0.3 (0.2-0.5) |

465.8 (58.2-3729.6) |

Abbreviations: NPV, negative predictive value; OR, odds ratio; PPV, positive predictive value.

Participants may have had biopsy specimens for DIF from different biopsy sites (1482 biopsy specimens were analyzed in 1125 patients).

Immunoserology

The sensitivity of the index IIF SSS test (n = 263) was 77.0% (95% CI, 72.2%-81.1%), and the specificity was 99.9% (95% CI, 99.3%-100.0%) (Table 1). Although IIF SSS had a statistically significantly lower sensitivity compared with DIF (77.0% vs 88.3%; P < .001), IIF SSS showed a high discriminative value with a positive predictive value of 99.6% (95% CI, 97.9%-99.9%) and a high diagnostic odds ratio of 2609.9 (95% CI, 361.3-18 851.9) (Table 1). The IIF SSS test was complementary to identify most patients with pemphigoid who had negative DIF findings (10.5%; Figure 2). Positive findings in IIF SSS were always confirmed by positivity in other serologic tests of different methodology (Figure 2). The sensitivities of IIF ME (57.1%; 95% CI, 51.9%-62.3%) and immunoblot (70.3%; 95% CI, 65.2%-74.9%) were substantially lower compared with the IIF SSS sensitivity, but they had high specificities (IIF ME: 98.8% [95% CI, 97.7%-99.4%]; immunoblot: 94.7% [95% CI, 92.8%-96.1%]) (Table 1). Four cases (1.2%) of pemphigoid diagnosis were made despite both negative DIF and IIF SSS findings at inclusion on the basis of pruritus with tense blisters, a compatible histopathologic result; and positive IIF ME, immunoblot, and ELISA results. Follow-up data available for 3 of these 4 cases revealed positive DIF finding during the disease course.

Figure 2. Ratios of Immunoreactivity in Various Diagnostic Tests in Patients With Confirmed Diagnosis of Pemphigoid.

The overlap in positivity of direct immunofluorescence (DIF) microscopy and indirect immunofluorescence on human salt-split skin (IIF SSS) substrate covering the near full circle represents the 98.8% of patients with pemphigoid. ELISA indicates enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

The sensitivity of BP180 NC16A ELISA was 70.0% (95% CI, 64.9%-74.6%) and BP230 ELISA was 44.6% (95% CI, 39.9%-49.9%) (Table 1). Single false-positive test results of BP180 NC16A were seen in 57 nonpemphigoid controls (11.3%) and of BP230 in 31 controls (7.2%), which included cases with toxic epidermal necrolysis, burns, psoriasis, and atopic dermatitis. In patients with pemphigoid, ELISA detected mean (SD) serum concentrations of anti–BP180 NC16A of 48.8 (50.4) U/mL (eFigure 3 in the Supplement) and anti–BP230 IgG autoantibodies of 25.6 (35.0) U/mL (eFigure 5 in the Supplement) compared with 2.4 (9.3; range, 0-115 U/mL) U/mL and 1.5 (5.3; range, 0-50) U/mL in controls. Performance of combined ELISAs BP180 NC16A and BP230 had a sensitivity of 79.0% (95% CI, 74.4%-82.9%) at the cost of a lower specificity of 83.6% (95% CI, 79.8%-86.8%). Intending to use BP180 NC16A and BP230 in initial diagnosis and to prevent the high number of false-positives, we calculated the positivity cutoff values using receiver operating characteristic curve analysis (eFigures 2 and 4 in the Supplement) and specificity comparable to that of DIF and IIF SSS tests (98%). Hence, the positivity cutoff for BP180 NC16A was 30 U/mL, with a corresponding sensitivity of 49.7%, whereas the cutoff for BP230 was set at 15 U/mL, with corresponding sensitivity of 38.8%.

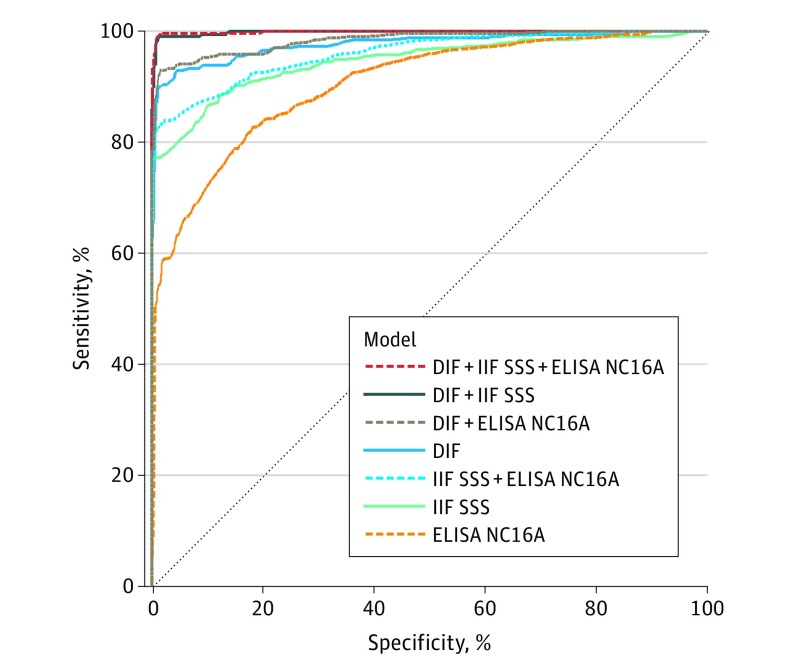

Diagnostic Strategy by Multivariable Logistic Regression Analysis

Presence of skin blisters was the highest predictive factor in the diagnosis of pemphigoid (univariate OR, 7.7; 95% CI, 5.7-10.5). Categorical 5-year age groups (ranging from <49 to >90 years) showed an incremental association with pemphigoid at age greater than 60 years (OR range, 1.96 [95% CI, 1.09-3.53]-9.66 [95% CI, 4.95-18.86]; eTable in the Supplement). On the contrary, pruritus was not a factor (OR, 0.6; 95% CI, 0.3-1.2), but it often was the reason to suggest pemphigoid. Eventually, no substantial value was seen in performing BP180 NC16A ELISA in addition to conducting a combined DIF and IIF SSS test because of overlapping 95% CIs (Figure 3). The combined performance of the DIF and IIF SSS test for pemphigoid diagnosis in this cohort reached a sensitivity of 98.8% (95% CI, 97.0%-99.7%) and specificity of 99.1% (95% CI, 98.2%-99.6%) (Table 1).

Figure 3. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Curves and Area Under the Curves (AUC) of (Combined) Diagnostic Tests for Pemphigoid Using Multivariable Logistic Regression Modeling.

The overlap between model DIF + IIF SSS and model DIF + IIF SSS + NC16A ELISA indicates no statistically significant difference in AUC and no diagnostic value added by NC16A ELISA to the DIF and IIF SSS tests. DIF indicates direct immunofluorescence microscopy; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; IIF SSS, indirect immunofluorescence on human salt-split skin substrate.

Bullous vs Nonbullous Pemphigoid

In a subgroup analysis of patients with bullous or nonbullous pemphigoid, a positive DIF finding was observed (213 of 239 cases [89.1%] vs 60 of 74 cases [81.1%]; P = .07). A statistically significant lower frequency of C3c depositions was observed in patients with nonbullous pemphigoid compared with those with bullous pemphigoid (52% vs 77%; P < .001), but no difference in IgG or IgA was found. Positive IIF SSS results were seen in 182 of 239 patients (76.2%) with bullous pemphigoid and 52 of 74 patients (70.3%) with nonbullous pemphigoid (P = .31). Sensitivity and specificity of combined DIF and IIF SSS tests did not differ between patients with bullous or nonbullous pemphigoid (Table 1). In contrast, for combined DIF test and BP180 NC16A ELISA, lower specificity, positive predictive value, and diagnostic OR were seen in patients with nonbullous pemphigoid (Table 1), indicating that false-positivity in BP180 NC16A ELISA was more commonly observed in patients with the nonbullous variant than in other participants.

Presence of circulating BP180 antibodies was associated with a bullous phenotype (80.3%; univariate OR, 2.6; 95% CI, 1.5-4.6; P < .001). In patients with nonbullous pemphigoid, single reactivity against BP230 was seen more often along with absence of serum autoantibodies against BP180 (18%; P < .001) (eFigure 6 in the Supplement). The mean (SD) serum concentration of anti–BP180 NC16A IgG detected by ELISA was statistically significantly lower in patients with nonbullous pemphigoid compared with patients with bullous pemphigoid (27.7 [34.9] U/mL vs 53.9 [52.9] U/mL; P < .001), whereas serum concentrations of anti-BP230 IgG were similar in both groups. Furthermore, the sole presence of BP230 autoantibodies was associated with a negative skin biopsy result for DIF (10.2%; univariate OR, 5.5; 95% CI, 2.7-11.3; P < .001), whereas the sole presence of BP180 autoantibodies was associated with a positive DIF result (69.7%; univariate OR, 2.5; 95% CI, 1.2-4.9; P = .01).

Discussion

These findings indicate that at least both DIF on a skin biopsy specimen and the IIF SSS serologic test should be performed for the optimal detection of 98.8% of pemphigoid cases. Although positive epidermal staining of IgG by IIF SSS is highly specific and confirmative for pemphigoid diagnosis, it is not sufficient to exclude pemphigoid because of its low sensitivity (77%). In contrast, performing the widely used BP180 NC16A ELISA had no additional value for initial diagnosis in our cohort and showed a high number of false-positives.

Sárdy et al13 reported similar findings in a retrospective comparative study, with sensitivities of 90% (DIF) and 73% (IF SSS) and specificities of 98% (DIF) and 100% (IF SSS), although these rates were hampered by a high number of missing serologic test data. The higher frequency of IgG (91%), compared with C3c (74%), positivity by DIF in our study can be explained by the saline incubation of most biopsy specimens, which lowers the high dermal background staining of IgG.18 Sensitivity of the DIF was lower in patients with nonbullous pemphigoid, whereas similar sensitivities were found for IIF SSS in patients with bullous and nonbullous pemphigoid. The high specificity of IIF SSS has been reported many times.13,21,22,23,24 The diagnostic test accuracy of IIF ME was congruent with other studies and highly specific, but it had a low sensitivity of 57% and was inferior to IIF SSS.13 Sensitivity of IIF might have been raised when IgG was specifically stained by a mixture of subclass specific antibodies (eg, IgG1, IgG4).25

Our results indicated that patients with nonbullous pemphigoid more often have BP230 as a target antigen and lower serum titers of autoantibodies against the immunodominant BP180 compared with patients with bullous pemphigoid. Patients with antibodies against BP230 often had significantly more negative DIF results, and the antibodies against BP230 contributed mainly to IIF positivity.13,20,24 A hypothesis is that antibodies against BP230 bind less to the intracellular target antigen in vivo in a skin biopsy specimen, but they bind to tissue sections of salt-split skin in vitro in which the BP230 antigen is exposed.21,26

A meta-analysis of the BP180 NC16A ELISA (both commercial and in-house made) analyzed 17 studies with 538 patients with bullous pemphigoid and reported a pooled sensitivity of 87% and specificity of 98%, with the authors concluding that ELISA can be used as a diagnostic screening test in patients with autoimmune bullous diseases.14 In contrast, we report a low diagnostic performance for ELISA, which is in line with several reports by other investigators.13,27 Sensitivity and specificity vary with the cutoff chosen for ELISA and are not intrinsic to the test but critically dependent on the context of tested participants. Consequently, differences in study design and methodologic flaws of previous studies may have led to an overestimation of diagnostic test accuracy (eg, selection bias and spectrum bias with evident [bullous] disease and positive DIF or immunoserologic results), controls of healthy participants or blood donors not representative of the patient domain, variation of the reference standard, and a substantially lower number of participants. Commercially available ELISAs have a simple standardized readout, but to prevent the high number of false-positives, a substantially higher cutoff value would be needed, resulting in low sensitivities with no clinical use. Similar findings of a false-positive rate of 14.3% of the BP180 NC16A ELISA and a recommended higher positivity cutoff value have recently been reported in dermatology patients with suspected pemphigoid.27 Therefore, based on our findings, performing ELISA is recommended solely for monitoring relative disease activity in patients with confirmed pemphigoid instead of as an initial diagnostic test.28,29 Moreover, a survey in Germany indicated that DIF and IIF SSS were the most commonly used diagnostic tests, with the required expertise available in 98% (DIF) and 74% (IIF SSS) of university and nonuniversity hospitals.30

The available clinical criteria for bullous pemphigoid are not applicable in patients with the nonbullous variant.8,9 Although histopathologic examination of a lesional skin biopsy specimen of a blister can support the diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid, it is neither sufficient nor essential for diagnosis and cannot distinguish between other subtypes of sAIBD.12,31 Moreover, histopathologic study is often nonspecific in nonbullous pemphigoid and indistinguishable from other inflammatory dermatoses.3

These findings suggest that at least both DIF and IIF SSS tests should be performed for the diagnosis of pemphigoid. Subsequently, the minimal diagnostic criteria we propose for pemphigoid diagnosis consist of at least 2 positive results out of 3 criteria (2-out-of-3 rule): (1) pruritus and/or predominant cutaneous blisters, (2) linear IgG and/or C3c deposits (in an n-serrated pattern) by DIF on a skin biopsy specimen, and (3) positive epidermal side staining by IIF SSS on a serum sample. The minimal diagnostic criteria thus contradict that presence of blisters or a histopathologic finding is a prerequisite for diagnosing pemphigoid. To distinguish pemphigoid from other sAIBD, the predominance of cutaneous lesions opposes mucous membrane pemphigoid. The finding of a positive result DIF with linear IgG depositions with undetermined serration pattern along the basement membrane zone does not always imply a definitive diagnosis of pemphigoid. The required performance of an IIF SSS test excludes the subtypes of sAIBD with dermal side binding of autoantibodies: anti–p200 or laminin γ1 pemphigoid, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita or bullous systemic lupus erythematosus, and anti–laminin-332 mucous membrane pemphigoid. Linear IgA disease is excluded by the sole detection of the autoantibodies of IgA isotype and pemphigoid gestationis by the distinct patient population. Subtyping in seronegative patients requires routine DIF serration-pattern analysis to identify the n-serrated pattern in pemphigoid, as opposed to the linear u-serrated pattern in epidermolysis bullosa acquisita.17

The nosologic entity bullous pemphigoid, postulated 65 years ago by Lever,32 was adapted to simply pemphigoid in the United Kingdom to avoid redundancy.33 Therefore, we advocate the use of pemphigoid to encompass both the bullous and nonbullous variants of this cutaneous autoimmune disease that typically presents as a pruritic dermatosis in older people, with or without skin blistering.

Limitations

The limitation of this study is the absence of diagnostic criteria as a reference standard for the diagnosis of pemphigoid. A limitation of all studies of diagnostic accuracy is the inability to incorporate the results of analyzed tests.

Conclusions

We propose minimal diagnostic criteria that encompass the complete clinical spectrum of pemphigoid. These criteria also differentiate pemphigoid from other sAIBD.

eAppendix. STARD 2015 checklist

eFigure 1. Flow chart complementary to Figure 2

eFigure 2. ROC curve, AUC and cross tabulation of BP180 NC16A ELISA

eFigure 3. Distribution of test results of BP180 NC16A ELISA

eFigure 4. ROC curve, AUC and cross tabulation of BP230 ELISA

eFigure 5. Distribution of test results of BP230 ELISA

eFigure 6. Distribution of target autoantigens BP180 and BP230 in patients with pemphigoid

eTable. Distribution of age groups and predictive value for diagnosis of pemphigoid

eMethods. Research Protocol and Laboratory Protocol (IIF SSS)

References

- 1.Joly P, Baricault S, Sparsa A, et al. . Incidence and mortality of bullous pemphigoid in France. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132(8):1998-2004. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.della Torre R, Combescure C, Cortés B, et al. . Clinical presentation and diagnostic delay in bullous pemphigoid: a prospective nationwide cohort. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167(5):1111-1117. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.11108.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lamberts A, Meijer JM, Jonkman MF. Nonbullous pemphigoid: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(5):989-995.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.10.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bakker CV, Terra JB, Pas HH, Jonkman MF. Bullous pemphigoid as pruritus in the elderly: a common presentation. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149(8):950-953. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmidt E, Zillikens D. Pemphigoid diseases. Lancet. 2013;381(9863):320-332. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61140-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Langan SM, Smeeth L, Hubbard R, Fleming KM, Smith CJ, West J. Bullous pemphigoid and pemphigus vulgaris–incidence and mortality in the UK: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2008;337:a180. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lipsker D, Borradori L. “Bullous” pemphigoid: what are you? urgent need of definitions and diagnostic criteria. Dermatology. 2010;221(2):131-134. doi: 10.1159/000316104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vaillant L, Bernard P, Joly P, et al. ; French Bullous Study Group . Evaluation of clinical criteria for diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134(9):1075-1080. doi: 10.1001/archderm.134.9.1075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joly P, Courville P, Lok C, et al. ; French Bullous Study Group . Clinical criteria for the diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid: a reevaluation according to immunoblot analysis of patient sera. Dermatology. 2004;208(1):16-20. doi: 10.1159/000075040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Venning VA, Taghipour K, Mohd Mustapa MF, Highet AS, Kirtschig G. British Association of Dermatologists’ guidelines for the management of bullous pemphigoid 2012. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167(6):1200-1214. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feliciani C, Joly P, Jonkman MF, et al. . Management of bullous pemphigoid: the European Dermatology Forum consensus in collaboration with the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172(4):867-877. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmidt E, Goebeler M, Hertl M, et al. . S2k guideline for the diagnosis of pemphigus vulgaris/foliaceus and bullous pemphigoid. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2015;13(7):713-727. doi: 10.1111/ddg.12612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sárdy M, Kostaki D, Varga R, Peris K, Ruzicka T. Comparative study of direct and indirect immunofluorescence and of bullous pemphigoid 180 and 230 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(5):748-753. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tampoia M, Giavarina D, Di Giorgio C, Bizzaro N. Diagnostic accuracy of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) to detect anti-skin autoantibodies in autoimmune blistering skin diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Autoimmun Rev. 2012;12(2):121-126. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2012.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, et al. ; STARD Group . STARD 2015: an updated list of essential items for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies. BMJ. 2015;351:h5527. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h5527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wet medisch-wetenschappelijk onderzoek met mensen. Dutch government website. https://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0009408/2018-08-01#. Accessed November 7, 2018.

- 17.Meijer JM, Atefi I, Diercks GFH, et al. . Serration pattern analysis for differentiating epidermolysis bullosa acquisita from other pemphigoid diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(4):754-759.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.11.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vodegel RM, de Jong MC, Meijer HJ, Weytingh MB, Pas HH, Jonkman MF. Enhanced diagnostic immunofluorescence using biopsies transported in saline. BMC Dermatol. 2004;4:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-5945-4-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vodegel RM, Jonkman MF, Pas HH, de Jong MC. U-serrated immunodeposition pattern differentiates type VII collagen targeting bullous diseases from other subepidermal bullous autoimmune diseases. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151(1):112-118. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.06006.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pas HH. Immunoblot assay in differential diagnosis of autoimmune blistering skin diseases. Clin Dermatol. 2001;19(5):622-630. doi: 10.1016/S0738-081X(00)00176-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gammon WR, Briggaman RA, Inman AO III, Queen LL, Wheeler CE. Differentiating anti-lamina lucida and anti-sublamina densa anti-BMZ antibodies by indirect immunofluorescence on 1.0 M sodium chloride–separated skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1984;82(2):139-144. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12259692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelly SE, Wojnarowska F. The use of chemically split tissue in the detection of circulating anti-basement membrane zone antibodies in bullous pemphigoid and cicatricial pemphigoid. Br J Dermatol. 1988;118(1):31-40. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1988.tb01747.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghohestani RF, Nicolas JF, Rousselle P, Claudy AL. Diagnostic value of indirect immunofluorescence on sodium chloride-split skin in differential diagnosis of subepidermal autoimmune bullous dermatoses. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133(9):1102-1107. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1997.03890450048006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Charneux J, Lorin J, Vitry F, et al. . Usefulness of BP230 and BP180-NC16a enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays in the initial diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid: a retrospective study of 138 patients. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147(3):286-291. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2011.23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jankásková J, Horváth ON, Varga R, et al. . Increased sensitivity and high specificity of indirect immunofluorescence in detecting IgG subclasses for diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43(3):248-253. doi: 10.1111/ced.13371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mutasim DF, Takahashi Y, Labib RS, Anhalt GJ, Patel HP, Diaz LA. A pool of bullous pemphigoid antigen(s) is intracellular and associated with the basal cell cytoskeleton-hemidesmosome complex. J Invest Dermatol. 1985;84(1):47-53. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12274684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu Z, Chen L, Zhang C, Xiang LF. Circulating anti-bullous pemphigoid 180 autoantibody can be detected in a wide clinical spectrum: a cross-sectional study [published online June 12, 2018]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmidt E, Obe K, Bröcker EB, Zillikens D. Serum levels of autoantibodies to BP180 correlate with disease activity in patients with bullous pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136(2):174-178. doi: 10.1001/archderm.136.2.174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fichel F, Barbe C, Joly P, et al. . Clinical and immunologic factors associated with bullous pemphigoid relapse during the first year of treatment: a multicenter, prospective study. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150(1):25-33. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.5757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Beek N, Knuth-Rehr D, Altmeyer P, et al. . Diagnostics of autoimmune bullous diseases in German dermatology departments. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2012;10(7):492-499. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2011.07840.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hodge BD, Roach J, Reserva JL, et al. . The spectrum of histopathologic findings in pemphigoid: avoiding diagnostic pitfalls. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45(11):831-838. doi: 10.1111/cup.13343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lever WF. Pemphigus. Medicine (Baltimore). 1953;32(1):1-123. doi: 10.1097/00005792-195302000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Waddington E. Pemphigus and pemphigoid. Br J Dermatol. 1953;65(12):425-431. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1953.tb13181.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix. STARD 2015 checklist

eFigure 1. Flow chart complementary to Figure 2

eFigure 2. ROC curve, AUC and cross tabulation of BP180 NC16A ELISA

eFigure 3. Distribution of test results of BP180 NC16A ELISA

eFigure 4. ROC curve, AUC and cross tabulation of BP230 ELISA

eFigure 5. Distribution of test results of BP230 ELISA

eFigure 6. Distribution of target autoantigens BP180 and BP230 in patients with pemphigoid

eTable. Distribution of age groups and predictive value for diagnosis of pemphigoid

eMethods. Research Protocol and Laboratory Protocol (IIF SSS)