Abstract

This population-based study describes the incidence, latency period, and outcomes of radiotherapy-associated angiosarcoma among patients with breast cancer from the Netherlands Cancer Registry.

Radiotherapy-associated angiosarcoma (RAAS) has been reported as a rare, but serious late complication of radiotherapy (RT) for breast cancer.1,2 This study describes the incidence, latency period, and outcomes of RAAS using the prospective database from the nationwide Netherlands Cancer Registry.

Methods

Patients who were treated with or without RT for stages I to III primary breast cancer from January 1, 1989, through December 31, 2015, with follow-up completed January 31, 2017, were retrospectively studied. A competing risk model (according to Fine and Gray3) was used to determine the incidence and predictive factors of RAAS. Survival after treatment of RAAS was analyzed using Kaplan-Meier curves. The Cox proportional hazards regression model was used for multivariable analysis. Follow-up was defined as the time from incidence of RAAS until the date of death or the last date of follow-up. Statistical significance was defined as 2-sided P < .05. Data were analyzed from January 1, 1989, through January 1, 2017. Following good clinical practice rules in the Netherlands, one does not need to ask ethical approval for the use of anonymized cohort data.

Results

Among the population of 296 577 patients included in the analysis (median age at diagnosis, 58 years [range, 18-97 years]), median follow-up after diagnosis of breast cancer was 7.7 years (range, 0-28.1 years). Of the patients who did not receive RT (n = 111 754), none developed an angiosarcoma. Of the 184 823 patients who received RT, 209 (0.1% [1 of 1000]) developed RAAS of the breast and/or chest wall (Table). Older patients with breast cancer were at increased risk for the development of RAAS (hazard ratio [HR], 1.05; 95% CI, 1.04-1.06). Patients who underwent a mastectomy for the primary tumor were less likely to develop RAAS compared with patients who underwent breast-conserving therapy (HR, 0.22; 95% CI, 0.10-0.49).

Table. Characteristics of Patients Who Received Radiotherapy After Surgery for the Primary Breast Cancer, 1989-2015.

| Features | Patient Group, No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| RAAS (n = 209) | No RAAS (n = 184 614)a | |

| Age at time of diagnosis, median (range), y | 65 (32-84) | 58 (18-97) |

| Incidence year | ||

| 1989-1995 | 57 (27.3) | 32 568 (17.6) |

| 1996-2002 | 74 (35.4) | 41 157 (22.3) |

| 2003-2009 | 69 (33.0) | 53 995 (29.2) |

| 2010-2015 | 9 (4.3) | 36 659 (19.9) |

| Unknown | 0 | 20 235 (11.0) |

| Clinical tumor stage | ||

| cTis | 0 | 1151 (0.6) |

| cT1 | 152 (72.7) | 105 315 (57.0) |

| cT2 | 30 (14.4) | 48 965 (26.5) |

| cT3 | 0 | 6798 (3.7) |

| cT4 | 1 (0.5) | 5807 (3.1) |

| cTx | 26 (12.4) | 16 340 (8.9) |

| Clinical node stage | ||

| cN0 | 167 (79.9) | 140 229 (76.0) |

| cN1-cN3 | 15 (7.2) | 32 789 (17.8) |

| cNx | 27 (12.9) | 11 596 (6.3) |

| Estrogen receptor status | ||

| Positive | 73 (34.9) | 91 470 (49.5) |

| Negative | 7 (3.3) | 11 463 (6.2) |

| Unknown | 129 (61.7) | 81 681 (44.2) |

| Progesterone receptor status | ||

| Positive | 58 (27.8) | 73 138 (39.6) |

| Negative | 20 (9.6) | 20 133 (10.9) |

| Unknown | 131 (62.7) | 91 343 (49.5) |

| Tumor differentiation | ||

| Well | 42 (20.1) | 32 094 (17.4) |

| Moderate | 64 (30.6) | 62 567 (33.9) |

| Poor | 44 (21.1) | 48 260 (26.1) |

| Unknown | 59 (28.2) | 41 461 (22.5) |

| Morphologic features | ||

| Ductal carcinoma | 155 (74.2) | 137 678 (74.6) |

| Lobular carcinoma | 21 (10.0) | 19 068 (10.3) |

| Other | 33 (15.8) | 27 868 (15.1) |

| Surgery | ||

| Mastectomy | 9 (4.3) | 43 095 (23.3) |

| Lumpectomy | 194 (92.8) | 136 884 (74.1) |

| NOS | 6 (2.9) | 4635 (2.5) |

| Axillary lymph node dissection | 152 (72.7) | 97 690 (52.9) |

| Hormone therapy | 70 (33.5) | 80 974 (43.9) |

| Chemotherapy | 22 (10.5) | 66 732 (36.1) |

| Targeted therapy | 2 (1.0) | 8970 (4.9) |

Abbreviations: NOS, not otherwise specified; RAAS, radiotherapy-associated angiosarcoma.

Owing to missing data, percentages may not total 100.

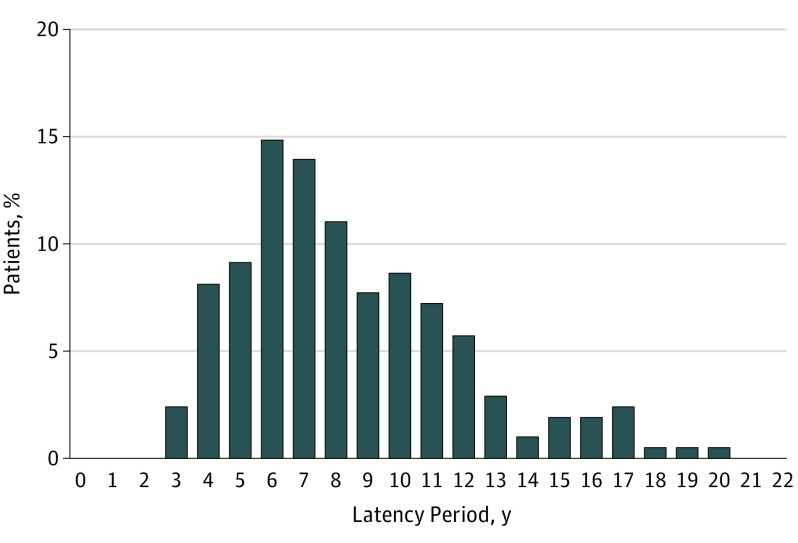

The median latency period from breast cancer treatment to development of RAAS was 8 years (range, 3-20 years) (Figure). Data on RAAS treatment were available in 194 patients (92.8%). Most patients underwent surgery only (166 [79.4%]). Nineteen patients (9.1%) underwent a combination of surgery and RT (9.1%), which was combined with hyperthermia therapy in 13. Three patients (1.4%) underwent a combination of surgery and chemotherapy and 6 (2.9%) underwent chemotherapy or RT only.

Figure. Overview of Latency Periods Between Diagnosis of Primary Breast Cancer and Diagnosis of Secondary Sarcoma.

Includes 209 patients with breast cancer and treated with radiotherapy ascertained from the Netherlands Cancer Registry.

Regardless of the treatment given for RAAS, 5- and 10-year overall survival rates were 40.5% (95% CI, 33.1%-47.9%) and 25.2% (95% CI, 17.4%-33.0%), respectively. Compared with surgery alone, the addition of RT to the treatment of RAAS did not significantly improve survival during univariable or multivariable analysis (HR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.28-1.34).

Discussion

The present study provides the largest original series of RAAS to date (n = 209), to our knowledge. The cumulative incidence of RAAS in 1 per 1000 patients with breast cancer who underwent RT is comparable with numbers as reported in the literature in smaller series of 0.9 to 1.1 per 1000 patients.4,5 Importantly, angiosarcomas did not occur in any of the patients who did not receive RT.

Overall 5-year survival in patients with RAAS was 40.5% without significant differences in treatment modalities. A recent review by Depla et al1 included all literature in the English language on RAAS from 1985 to 2013 and described 222 patients from case reports and small series. The investigators suggested that surgery in combination with RT might improve local control.1 Another study6 suggested a beneficial effect of hyperthermia therapy in combination with RT. None of the studies showed an association with overall survival. In the Netherlands Cancer Registry database, data on local recurrences is lacking, but similarly to previous studies, no statistically significant survival benefit was found in patients who underwent surgery and RT compared with patients who underwent surgery alone. However, the number of patients treated with surgery and RT was low in the present study.

Our data show that treatment of RAAS should include surgery. A beneficial effect on overall survival of the addition of RT to the treatment of RAAS could not be confirmed in this population-based analysis, and evidence in the literature also lacks power to draw firm conclusions. This study demonstrates that the low incidence of RAAS renders a prospective analysis practically not feasible. Entering the outcomes of RAAS into a prospective international database could be considered.

References

- 1.Depla AL, Scharloo-Karels CH, de Jong MA, et al. Treatment and prognostic factors of radiation-associated angiosarcoma (RAAS) after primary breast cancer: a systematic review. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50(10):1779-1788. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2014.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Torres KE, Ravi V, Kin K, et al. Long-term outcomes in patients with radiation-associated angiosarcomas of the breast following surgery and radiotherapy for breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(4):1267-1274. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2755-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94(446):496-509. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1999.10474144 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yap J, Chuba PJ, Thomas R, et al. Sarcoma as a second malignancy after treatment for breast cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;52(5):1231-1237. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(01)02799-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang J, Mackillop WJ. Increased risk of soft tissue sarcoma after radiotherapy in women with breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2001;92(1):172-180. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Linthorst M, van Geel AN, Baartman EA, et al. Effect of a combined surgery, re-irradiation and hyperthermia therapy on local control rate in radio-induced angiosarcoma of the chest wall. Strahlenther Onkol. 2013;189(5):387-393. doi: 10.1007/s00066-013-0316-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]