Key Points

Question

What are the key characteristics of necrotizing neutrophilic dermatosis?

Findings

In this case series involving 6 previously unreported patients with necrotizing neutrophilic dermatitis and a literature review involving 48 patients with necrotizing neutrophilic dermatosis, patients with pyoderma gangrenosum or Sweet syndrome had clinical features that mimicked severe infection, including fever, elevated inflammatory markers, leukemoid reaction, and shock. Debridements and amputations occurred, and antibiotics were prescribed with inadequate treatment response, but all patients responded to immunosuppressive treatment.

Meaning

Pyoderma gangrenosum and Sweet syndrome with prominent systemic inflammation define a subset of neutrophilic dermatoses, termed necrotizing neutrophilic dermatoses, which is frequently misdiagnosed as necrotizing fasciitis; its proper recognition may minimize morbidity associated with delayed or inappropriate treatment.

Abstract

Importance

Pyoderma gangrenosum and necrotizing Sweet syndrome are diagnostically challenging variants of neutrophilic dermatosis that can clinically mimic the cutaneous and systemic features of necrotizing fasciitis. Improved characterization of these rare variants is needed, as improper diagnosis may lead to inappropriate or delayed treatment and the potential for morbidity.

Objective

To determine the characteristics of necrotizing neutrophilic dermatosis to improve diagnostic accuracy and distinguish from infection.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A case series of patients with necrotizing neutrophilic dermatosis treated at 3 academic hospitals (University of California San Francisco, Oregon Health and Science University, and University of Minnesota) from January 1, 2015, to December 31, 2017, was performed along with a literature review of related articles published between January 1, 1980, and December 31, 2017. Data were obtained from medical records as well as Medline and Embase databases. All patients had signs resembling necrotizing infection and had a final diagnosis of pyoderma gangrenosum with systemic features or necrotizing Sweet syndrome. Patients were excluded if a diagnosis other than neutrophilic dermatosis was made, if key clinical information was missing, and if reported in a non-English language.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Description of key characteristics of necrotizing neutrophilic dermatosis.

Results

Overall, 54 patients with necrotizing neutrophilic dermatosis were included, of which 40 had pyoderma gangrenosum with systemic features and 14 had necrotizing Sweet syndrome. Of the 54 patients, 29 (54%) were male and 25 (46%) were female, with a mean (SD) age of 51 (19) years. Skin lesions commonly occurred on the lower (19 [35%]) and upper (13 [24%]) extremities and developed after a surgical procedure (22 [41%]) or skin trauma (10 [19%]). Shock was reported in 14 patients (26%), and leukemoid reaction was seen in 15 patients (28%). Of the patients with necrotizing neutrophilic dermatosis, 51 (94%) were initially misdiagnosed as necrotizing fasciitis and subsequently received inappropriate treatment. Debridement was performed in 42 patients (78%), with a mean (SD) of 2 (2 [range, 1-12]) debridements per patient. Four amputations (7%) were performed. Forty-nine patients (91%) received antibiotics when necrotizing neutrophilic dermatosis was misdiagnosed as an infection, and 50 patients (93%) received systemic corticosteroids; all patients responded to immunosuppressants.

Conclusions and Relevance

A complex spectrum of clinical findings of pyoderma gangrenosum and Sweet syndrome with prominent systemic inflammation exists that defines a new subset of neutrophilic dermatoses, termed necrotizing neutrophilic dermatoses; recognizing the difference between this variant and severe infection may prevent unnecessary surgical procedures and prolonged disease morbidity associated with a misdiagnosis and may expedite appropriate medical management.

This case series examines 6 previously unreported patients and published reports of 48 patients with necrotizing neutrophilic dermatosis to identify the traits and infection-mimicking features of a new subset of necrotizing neutrophilic dermatosis.

Introduction

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) with systemic inflammation and necrotizing Sweet syndrome (NSS) frequently mimic severe infection. A subset of diagnostically challenging neutrophilic dermatoses morphologically resemble necrotizing fasciitis (NF) with rapid progression of purpura and skin necrosis in a critically ill patient. They prominently feature systemic inflammation with sepsis-like physiologic signs (fever, leukocytosis, tachycardia, hypotension, and organ failure) and neutrophilic dermatosis with no infectious cause. The distinction between infection and inflammation is difficult, as the clinical picture closely mimics sepsis resulting from infection; however, blood and tissue cultures are negative.1,2 Often, misdiagnosis leads to delayed or failed treatment. Because the immunosuppression used to treat neutrophilic inflammation may worsen the infection and the surgical procedures that target the infection may exacerbate PG or NSS through pathergy, refining the diagnosis and management of this inflammatory variant, termed here as necrotizing neutrophilic dermatosis (NND), is important.

Methods

We describe a case series of patients with NND seen at 3 academic institutions (University of California San Francisco, Oregon Health and Science University, and University of Minnesota) from January 1, 2015, to December 31, 2017, along with results of a literature review. Data were derived retrospectively from medical records or from published reports in Medline and Embase databases using the search terms pyoderma gangrenosum or Sweet syndrome (SS) and necrotizing fasciitis. Two of us (I.M.S. and S.L.) independently reviewed and selected studies published between January 1, 1980, and December 31, 2017.3 An additional reviewer (K.S.) resolved the discrepancies between our 2 reviewers. Necrotizing was defined as severe systemic features in a critically ill patient with a clinical diagnosis of PG or SS that mimics sepsis or septic shock from infection, are often accompanied by the breakdown of skin through the dermis and fat, and considered as NF in the differential diagnosis (inclusion criteria for cases). Shock was defined as a multiorgan dysfunction in a critically ill patient resulting from dysregulated inflammation; typical signs of shock include fever, respiratory distress, tachycardia, hypotension, leukocytosis, metabolic abnormalities, and altered mentation.4 Sepsis by definition requires infection as a cause, but the clinical presentation of sepsis or shock in our review had no infectious origin. Cases were excluded if a diagnosis other than neutrophilic dermatosis was made, if key clinical details were missing, or if reported in a non-English language. The data were analyzed using STATA version 14.2, Special Edition (StataCorp LLC).

The institutional review boards of the University of California, San Francisco, the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and the Oregon Health Sciences University, Portland, approved or exempted the reporting of cases derived from each institution.

Results

In total, we found 48 patients with NND, 36 patients with necrotizing PG, and 12 patients with NSS reported in the literature. Along with an additional 6 unpublished patients with NND (2 PG and 4 NSS) found on medical record review at 3 academic institutions, this case series illustrates the spectrum of disease presentation, highlighting possible clinical criteria (Table 1). Most patients had clinical lesions with prominent systemic inflammation, which resembled sepsis or shock. Overall, 54 patients with NND were included, of which 40 were PG with systemic features and 14 were NSS. Of the 54 patients, 29 (54%) were male and 25 (46%) were female, with a mean (SD) age of 51 (19) years.

Table 1. Necrotizing Neutrophilic Dermatosis: Proposed Diagnostic Criteria.

| Criteria | Presentation |

|---|---|

| Major | |

| Cutaneous manifestation | Necrotizing pyoderma gangrenosum or necrotizing Sweet syndrome: Typically ulcers or erythematous plaques leading to skin breakdown Often with purpura, purulence or pustules, and/or edema Often with erythematous-violaceous borders Satellite lesions |

| Systemic involvement | Fever (>38.3°C) Shock (critically ill patient; resembling sepsis without infection) Leukemoid reaction (≥30 000/μL) or leukocytosis (≥11 000/μL) |

| Microbiologic finding | Absence of infectious organisms on bacterial and fungal histopathologic tissue stains or direct microscopy (Gram stain, PAS or GMS stain, KOH) Negative tissue cultures |

| Histopathologic feature | Diffuse subcutaneous and dermal inflammation with a predominance of neutrophils, associated leukocytoclasis, and edema Neutrophilic infiltrate and associated necrosis extending to fascia or muscle |

| Treatment response | Dramatic improvement with corticosteroids Lack of response or clinical worsening with antibiotics, debridement, incision and drainage, or amputation |

| Minor | |

| Comorbidities | Hematologic disorders and malignant neoplasms Inflammatory bowel disease Connective tissue disease Pregnancy Medications (G-CSF) |

| History of pathergy | Surgical procedure (including amputation, debridement, or incision and drainage) Abrasion Venipuncture, injection, or intravenous site |

Abbreviations: G-CSF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; GMS, Grocott methenamine silver; KOH, potassium hydroxide; PAS, periodic acid–Schiff.

SI conversion factor: To convert leukocytes or white blood cell count to ×109/L, multiply by 0.001.

Of the patients with NND, 51 (94%) were initially misdiagnosed as NF (Table 2), and NND occurred more often among male patients and had a mean (SD) age at onset of 51 (19) years. In all 54 patients, hematologic disorders and malignant neoplasms were the most common disease associations (18 [33%]), with myelodysplastic syndrome occurring in 9 patients (17%). Other common comorbidities were connective tissue disease (6 [11%]), endocrine disorders (7 [13%]), and inflammatory bowel disease (6 [11%]). Medications were potential triggers in 7 patients (13%), including granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in 4 cases (7%). Illicit drug use was reported in 1 patient (2%). Initial pathergic insults included surgical procedure (22 [41%]) or trauma (10 [19%]).

Table 2. Characteristics of Necrotizing Neutrophilic Dermatosis.

| Variable | Overall (n = 54) | PG (n = 40) | NSS (n = 14) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 51 (18) | 51 (18) | 51 (18) |

| Male sex, No. (%) | 29 (54) | 17 (43) | 12 (86) |

| Site involved, No. (%) | |||

| Leg and pelvisa | 21 (39) | 16 (40) | 5 (36) |

| Armb | 13 (24) | 9 (23) | 4 (29) |

| Abdomen | 8 (15) | 6 (15) | 2 (14) |

| Head and neck | 6 (11) | 3 (8) | 3 (21) |

| Breast | 5 (9) | 5 (13) | 0 |

| Comorbidity, No. (%)c | |||

| None | 15 (28) | 14 (35) | 1 (7) |

| Hematologic disorders and malignant neoplasms | 18 (33) | 9 (23) | 9 (64) |

| Solid organ malignant neoplasm | 4 (7) | 2 (5) | 2 (14) |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 6 (11) | 4 (10) | 2 (14) |

| Connective tissue disease | 6 (11) | 4 (10) | 2 (14) |

| Endocrine disorder | 7 (13) | 4 (10) | 3 (21) |

| Pregnancy | 3 (6) | 2 (5) | 1 (7) |

| Infectious disease | 3 (6) | 2 (5) | 1 (7) |

| Otherd | 10 (19) | 6 (15) | 4 (29) |

| Concomitant medication, No. (%) | |||

| G-CSF | 4 (7) | 1 (3) | 3 (21) |

| Bortezomib | 1 (2) | 0 | 1 (7) |

| Azathioprine sodium | 1 (2) | 0 | 1 (7) |

| Initial insult, No. (%) | 25 (44) | 20 (50) | 5 (36) |

| Abrasion | 6 (11) | 6 (15) | 0 |

| Surgical proceduree | 22 (41) | 20 (50) | 2 (14) |

| Venipuncture, injection, or IV site | 4 (7) | 2 (5) | 2 (14) |

| Medication induced | 7 (13) | 1 (3) | 6 (43) |

| None | 18 (33) | 11 (28) | 7 (50) |

| Clinical presentation, No. (%)c | |||

| Erythema | 41 (76) | 27 (68) | 13 (93) |

| Ulcers | 25 (46) | 25 (63) | 0 (0) |

| Purulence/pustules | 23 (43) | 18 (45) | 6 (43) |

| Violaceous marginsf | 16 (30) | 13 (33) | 4 (29) |

| Necrosis | 16 (30) | 10 (25) | 6 (33) |

| Plaques | 11 (20) | 3 (8) | 8 (57) |

| Edema | 17 (31) | 10 (25) | 7 (50) |

| Satellite lesions | 14 (26) | 8 (20) | 6 (33) |

| Diagnostic testing/laboratory finding | |||

| Leukemoid reaction, No. (%)g | 15 (28) | 10 (25) | 4 (29) |

| Leukocytosis, No. (%)h | 36 (67) | 25 (63) | 11 (79) |

| CRP mean (SD), mg/L | 288 (450) | 324 (502) | 158 (131) |

| Temperature maximum, mean (SD), °C | 40 (1) | 39 (1) | 40 (1) |

| Fever, No. (%)i | 36 (67) | 22 (55) | 14 (100) |

| Sepsis/shock, No. (%) | 14 (26) | 12 (30) | 3 (21) |

| Biopsy, No. (%) | 51 (94) | 37 (93) | 14 (100) |

| Imaging, No. (%) | 19 (35) | 11 (28) | 8 (57) |

| Treatment regimen, No. (%) | |||

| Antibiotics | 49 (91) | 36 (90) | 13 (93) |

| Corticosteroids | 50 (93) | 36 (90) | 14 (100) |

| Colchicine | 2 (4) | 0 | 2 (14) |

| Cyclosporine | 10 (19) | 7 (18) | 3 (21) |

| Infliximab | 3 (6) | 2 (5) | 1 (7) |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 2 (4) | 2 (5) | 0 |

| Surgical therapy, No. (%) | |||

| Debridement | 42 (78) | 33 (83) | 9 (64) |

| Mean (SD) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Amputation | 4 (7) | 3 (8) | 1 (7) |

| Incision and drainage | 3 (6) | 3 (8) | 0 |

Abbreviations: CRP, C-reactive protein; G-CSF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; IV, intravenous; NSS, necrotizing Sweet syndrome; PG, pyoderma gangrenosum.

SI conversion factors: To convert C-reactive protein level to nanomoles per liter, multiply by 9.524; leukocytes or white blood cell count to ×109/L, multiply by 0.001.

Leg included lower extremity, including leg (12), foot (2), thigh (2), knee (2), ankle (1), and buttocks (2).

Arm included upper extremity, including arm (8), shoulder (3), and hand (2).

Total sum is more than 100% because of multiple responses per case.

Other included chemical burn, hypertension, and interstitial lung disease.

Surgical procedure included any operation (21) or excision (1).

Violaceous margins were defined and may have occurred at any time during the disease course, including postdebridement.

Leukemoid reaction was defined as leukocytes or white blood cell count of 30 000/μL or greater.5

Leukocytosis was defined as leukocytes or white blood cell count of 11 000/μL or greater.5

Fever was defined as higher than 38.3°C.

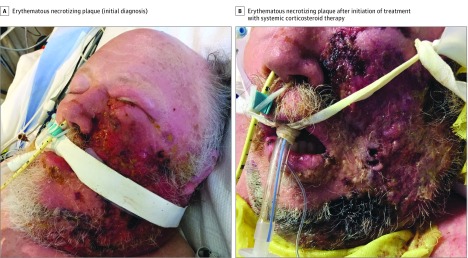

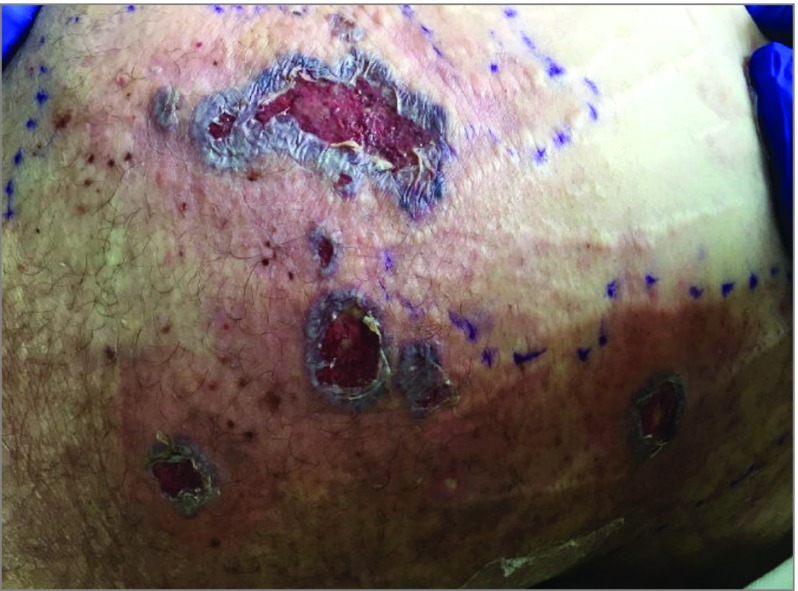

Common cutaneous findings were erythema (41 [76%]), ulcers (25 [46%]), and necrosis (16 [30%]; see Figure 1). Similar prevalence of violaceous margins and necrosis were seen in PG and NSS (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). Skin lesions were located on the lower (19 [35%]) and upper (13 [24%]) extremities. Of the 14 NND cases (26%) with satellite lesions, 8 (57%) were associated with PG and 6 (43%) with NSS (see Figure 2).

Figure 1. Necrotizing Sweet Syndrome With Pyoderma Gangrenosum–like Features.

A patient in his 60s with myelodysplastic syndrome (A) developed an erythematous necrotizing plaque on his left malar cheek (B). Necrotizing soft tissue infection was initially suspected on the basis of his fever, shock, and multiorgan dysfunction. He received a diagnosis of hematologic malignant neoplasm–associated necrotizing Sweet syndrome with pyoderma gangrenosum–like features. His skin lesions had a complete clinical response to systemic corticosteroid therapy.

Figure 2. Satellite Lesions of Pyoderma Gangrenosum.

A previously healthy man in his 40s presented with an ulcerating purpuric, violaceous plaque with undermined borders on his right leg and multiple satellite lesions after recent methamphetamine use. Despite negative tissue cultures and failure to respond to multiple systemic antibiotics, he received a necrotizing fasciitis diagnosis because of his sepsis-like presentation and his expanding leg ulcer. An amputation occurred at an outside hospital. After a hospital transfer, in which a diagnosis of necrotizing neutrophilic dermatosis was made, he had rapid clinical improvement after receiving systemic corticosteroid therapy.

Systemic features were universal. Thirty-six patients (67%) were febrile (mean temperature, 40°C), and 14 (26%) presented with clinical signs resembling septic shock. Nineteen patients (35%) underwent diagnostic imaging. Cultures were performed in 45 cases (83%), and 98% percent of tissue cultures were negative. Key laboratory findings included elevated markers of systemic inflammation in 23 patients (43%), leukocytosis in 36 (67%), and a leukemoid reaction in 15 (28%), with a mean (range) white blood cell count of 51 371/μL (32 300-138 000/μL) (to convert to ×109/L, multiply by 0.001).5

Biopsy was performed in 51 patients (94%). Typical histopathologic findings were sparse diffuse subcutaneous and dermal inflammation with a predominance of neutrophils as well as associated leukocytoclasis and edema. The neutrophilic infiltrate and associated necrosis (43% of cases) often extended to the level of fascia or muscle. Evidence of vasculitis or an associated atypical or immature myeloid infiltrate was not observed (eFigures 2 and 3 in the Supplement).

Debridement was performed in 42 patients (78%), with a mean (SD) of 2 (2 [range, 1-12]) debridements per patient. Antibiotics were administered as an initial treatment in 49 patients (91%), and 50 patients (93%) were treated with systemic corticosteroids. Additional steroid-sparing immunosuppressants were also used in some patients. Four limb amputations (7%) occurred, and 30 patients (55%) involved dermatologic consultation to prevent 3 additional amputations.

Discussion

Neutrophilic dermatoses on a clinical spectrum range from typical cases to distinct variants with severe systemic involvement, which we refer to as NND. Common features of NND include necrotizing, erythematous, edematous plaques or ulcers with violaceous margins; pathergy; fever; shock; leukemoid reaction; elevated markers of systemic inflammation; histopathologic evidence of neutrophilic inflammation; sterile tissue cultures; lack of response to antibiotics; and improvement with systemic corticosteroids. In addition, NND is associated with systemic conditions similar to classic neutrophilic dermatosis, specifically hematologic disorders and malignant neoplasms, connective tissue disease, inflammatory bowel disease, and medications such as granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Also, NND may present with either SS- or PG-like morphologic features, and violaceous margins in NSS mimic typical PG after pathergic insults such as debridement. Several NSS cases developed concomitant classic SS-like lesions after their initial NF-like presentation.

Common features of NND were identified, but some clinical features may be indistinguishable from necrotizing soft-tissue infection, such as fever, leukemoid reaction, and shock, presenting a challenging clinical scenario as treatments for infection are distinct and diametrically opposed from treatments for inflammation. Multidisciplinary teams must reach a consensus about how to reconcile the differences in diagnosis and subsequent management. Diagnostic confusion in these cases, especially the 94% misdiagnosed as NF, was exacerbated by the inconsistent performance of imaging, cultures, and biopsy tests; this variation resulted in inappropriate treatment such as antibiotic administration, debridement, or amputation. Tissue biopsy specimens and cultures are critical to distinguishing the diagnosis of NND from NF, although in cases of NF, confirmatory tissue samples range from 43% to 98% and blood cultures range from 18% to 66%.6,7 Cultures are not always positive in NF, but classic cutaneous morphologic clues for PG or SS in the absence of infectious organisms on histopathologic, microbiologic stains or culture support an NND diagnosis; inpatient dermatologic consultation may also expedite diagnosis.2,8,9 Immunosuppression can be empirically initiated while waiting for cultures and additional histopathologic stains for infection, especially if a critically ill patient does not improve with antimicrobial agents and there is no clear evidence of infection.10 Concomitant treatment with corticosteroids and antimicrobial agents is an important and potentially lifesaving compromise of therapeutic management.

Although we noted some minor differences between PG-like and NSS forms of NND,11,12,13,14,15 we believe that necrotizing PG and NSS described in the literature are the same disease, an important variant distinct from classic neutrophilic dermatosis. However, NND may not fulfill existing diagnostic criteria for classic PG and SS; distinct underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms likely give rise to severe systemic involvement.2,12,15

Limitations

We highlight key features of NND proposed by the literature as diagnostic criteria; however, case reviews are limited by publication bias of poor outcomes, near misses, or missing information that affects results. An additional limitation was the use of clinical descriptions of shock without use of formal sepsis or Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome criteria. Prospective studies are needed to validate the proposed features as diagnostic criteria for NND. Future research is especially needed to elucidate specific diagnostic biomarkers to distinguish NND from infectious mimickers, define key pathways, and identify the best management.

Conclusions

This case series report characterizes NND features to aid in disease classification and diagnosis. The overlapping clinical characteristics suggest that this entity lies on the same disease spectrum of more classic neutrophilic dermatosis, yet it is a distinct variant. Clinical morphologic test as well as tissue biopsy and culture are critical to differentiating NND from NF. Refinement of the proposed clinical criteria is needed. These cases also highlight a practice gap for dermatologists: a lack of diagnostic criteria and biomarkers that accurately discriminate inflammation from infection.

eTable 1. New Cases of Necrotizing Neutrophilic Dermatosis Misdiagnosed As Necrotizing Fasciitis in San Francisco, CA; Portland, OR; Minneapolis, MN

eFigure 1. Necrotizing Sweet Syndrome Morphology Mimicking PG

eFigure 2. Necrotizing Sweet Syndrome Histopathology

eFigure 3. Necrotizing Sweet Syndrome Histopathology

eReferences

References

- 1.Braswell SF, Kostopoulos TC, Ortega-Loayza AG. Pathophysiology of pyoderma gangrenosum (PG): an updated review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(4):691-698. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.06.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kroshinsky D, Alloo A, Rothschild B, et al. . Necrotizing Sweet syndrome: a new variant of neutrophilic dermatosis mimicking necrotizing fasciitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67(5):945-954. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.02.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. ; PRISMA-P Group . Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4:1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. . The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315(8):801-810. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Potasman I, Grupper M. Leukemoid reaction: spectrum and prognosis of 173 adult patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57(11):e177-e181. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong CH, Chang HC, Pasupathy S, Khin LW, Tan JL, Low CO. Necrotizing fasciitis: clinical presentation, microbiology, and determinants of mortality. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A(8):1454-1460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brook I, Frazier EH. Clinical and microbiological features of necrotizing fasciitis. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33(9):2382-2387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Milani-Nejad N, Zhang M, Kaffenberger BH. Association of dermatology consultations with patient care outcomes in hospitalized patients with inflammatory skin diseases. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(6):523-528. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.6130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ko LN, Garza-Mayers AC, St John J, et al. . Effect of dermatology consultation on outcomes for patients with presumed cellulitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(5):529-536. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.6196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gonzalez Santiago TM, Pritt B, Gibson LE, Comfere NI. Diagnosis of deep cutaneous fungal infections: correlation between skin tissue culture and histopathology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(2):293-301. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.03.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inoue S, Furuta JI, Fujisawa Y, et al. . Pyoderma gangrenosum and underlying diseases in Japanese patients: a regional long-term study. J Dermatol. 2017;44(11):1281-1284. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.13937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maverakis E, Ma C, Shinkai K, et al. . Diagnostic criteria of ulcerative pyoderma gangrenosum: a Delphi consensus of international experts. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(4):461-466. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.5980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rochet NM, Chavan RN, Cappel MA, Wada DA, Gibson LE. Sweet syndrome: clinical presentation, associations, and response to treatment in 77 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(4):557-564. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.06.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruocco E, Sangiuliano S, Gravina AG, Miranda A, Nicoletti G. Pyoderma gangrenosum: an updated review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(9):1008-1017. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03199.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Su WP, Davis MD, Weenig RH, Powell FC, Perry HO. Pyoderma gangrenosum: clinicopathologic correlation and proposed diagnostic criteria. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43(11):790-800. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02128.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. New Cases of Necrotizing Neutrophilic Dermatosis Misdiagnosed As Necrotizing Fasciitis in San Francisco, CA; Portland, OR; Minneapolis, MN

eFigure 1. Necrotizing Sweet Syndrome Morphology Mimicking PG

eFigure 2. Necrotizing Sweet Syndrome Histopathology

eFigure 3. Necrotizing Sweet Syndrome Histopathology

eReferences