Abstract

Importance

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the most frequent malignant neoplasm found in solid organ transplant recipients and is associated with a more aggressive disease course and higher risk of metastasis and death than in the general population.

Objectives

To report the clinicopathologic features of and identify factors associated with aggressive SCC in solid organ transplant recipients.

Methods

This retrospective multicentric case series included 51 patients who underwent solid organ transplantation and were found to have aggressive SCC, defined by nodal or distant metastasis or death by local progression of primary SCC. Standard questionnaires were completed by the researchers between July 18, 2005, and January 1, 2015. Data were analyzed between February 22, 2016, and July 12, 2016.

Results

Of the 51 participants, 43 were men and 8 were women, with a median age of 51 years (range, 19-71 years) at time of transplantation and 62 years (range, 36-77 years) at time of diagnosis of aggressive SCC. The distribution of aggressive SCC was preferentially on the face (34 [67%]) and scalp (6 [12%]), followed by the upper extremities (6 [12%]). A total of 21 tumors (41%) were poorly differentiated, with a median tumor diameter of 18.0 mm (range, 4.0-64.0 mm) and median tumor depth of 6.2 mm (range, 1.0-20.0 mm). Perineural invasion was present in 20 patients (39%), while 23 (45%) showed a local recurrence. The 5-year overall survival rate was 23%, while 5-year disease-specific survival was 30.5%.

Conclusions and Relevance

Results of this case series suggest that anatomical site, differentiation, tumor diameter, tumor depth, and perineural invasion are important risk factors in aggressive SCC in solid organ transplant recipients.

This case series describes the clinicopathologic features of and identifies factors associated with aggressive squamous cell carcinoma in solid organ transplant recipients.

Key Points

Question

What factors are associated with aggressive squamous cell carcinoma in solid organ transplant recipients?

Findings

In this case series study of 51 patients, aggressive squamous cell carcinomas were preferentially localized on the face in 34 patients (67%). A total of 21 tumors (41%) were poorly differentiated, with a median tumor diameter of 18 mm and median tumor depth of 6.2 mm.

Meaning

As suggested by results of this case series, anatomical site, differentiation, tumor diameter, tumor depth, and perineural invasion are important risk factors in aggressive squamous cell carcinoma in solid organ transplant recipients.

Introduction

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is a malignant neoplasm deriving from epidermal keratinocytes. In the general population, SCC is the second most common form of keratinocyte carcinoma after basal cell basal cell carcinoma,1,2 and in organ transplant recipients SCC is the most common skin cancer.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11 Previous studies12,13,14,15 report a risk for nodal metastasis of 1.9% to 4.0% and a risk for disease-specific death of 1.5% to 2.1% in the general population.

The number of solid organ transplants and long-term survival in organ transplant recipients have increased over the 5 decades as a result of progress in both surgical techniques and drug-induced immunosuppression.16 Notwithstanding the clear benefits of successful allograft transplantation, organ transplant recipients experience important adverse effects from long-term immunosuppressive medication, including a 10-fold increased risk for malignant neoplasms overall.17,18 In particular, solid organ transplant recipients have a 65-fold to 250-fold higher incidence of SCC compared with those who have not received transplants. After transplantation, 20% to 75% of solid organ transplant recipients are affected by at least 1 SCC within 20 years.8,19 After a first invasive SCC, multiple subsequent SCCs will develop in 60% to 80% of these patients within 3 years. The risk of SCC increases over time, with the incidence increasing to 40% to 60% at 20 years after transplantation.20,21

Cutaneous SCC is also associated with a more aggressive behavior and a higher risk of metastasis and death in solid organ transplant recipients than in the general population.6,7,22 The rate of metastasis in solid organ transplant recipients is reported to be 5% to 8%.23

In addition to immunosuppression and time from transplantation, the factors for the development of SCC in solid organ transplant recipients are similar to those found in the general population, namely, male sex, older age, cumulative UV radiation exposure, and fair skin.1,7,8,24,25,26,27,28

Although most SCCs will be successfully treated, some show a very aggressive clinical course. Currently, the distinction between the many SCCs cured without sequelae and the few SCCs with an aggressive course can be hard to make at diagnosis. The objective of this study, based on a European case series of solid organ transplant recipients, is to describe clinicopathologic features of aggressive SCC and to identify factors that are associated with aggressive development of SCC in solid organ transplant recipients.

Methods

Clinical and histological data were retrospectively collected from 5 centers: Brussels, Belgium; Barcelona, Spain; Leiden, the Netherlands; London, United Kingdom; and Zurich, Switzerland, within the Skin Care in Organ Transplant Patients, Europe Network. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zurich, Switzerland (NCT02095912), who waived patient consent for deidentified data.

Inclusion criteria were patients who underwent solid organ transplantation and developed an aggressive SCC including nodal or distant metastasis or death by local progression of primary SCC. All patient identifiers were coded to ensure patient anonymity. Exclusion criteria were the absence of an aggressive SCC, mucosal head and neck SCC, or missing data. All participating centers were able to identify and retrieve information on organ transplant recipients with aggressive SCC from their archives. Standard questionnaires were completed by us between July 18, 2005, and January 1, 2015, and dates of analysis were February 22, 2016, to July 12, 2018. Patients were followed up from the date of first transplantation to date of death or the last dermatologist visit. Skin phototype classification was not recorded because of incomplete data at the time of inclusion. Data were obtained from the hospital database including patient medical records and pathology reports.

Disease-specific death was considered to have occurred if the treatment team documented that the patient died of a specific SCC or of complications that arose directly from SCC. Non–disease-specific death was considered to have occurred in patients who developed nodal or distant metastasis or a local, treatment-refractory tumor but died of other causes (eg, cardiac arrest).

Statistical Analysis

Clinical characteristics were summarized with the use of descriptive statistics and frequency tabulation. Overall survival, disease-specific survival, progression-free survival, and time from metastasis to death were analyzed by the Kaplan-Meier method. Statistical analysis was performed with IBM SPSS statistical software, version 23.0. (SPSS Inc). No significance testing was performed.

Results

Most of the 51 solid organ transplant recipients who developed an aggressive SCC were men (43 [84%]) and had received a kidney transplant (40 [78%]). Median age at diagnosis of aggressive SCC was 62 years (range, 36-77 years). Three patients (6%) underwent combined kidney and pancreas transplantation and 1 patient had a liver and lung transplant. Ten patients (20%) underwent 2 transplantations because of organ failure. Full characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Patient Characteristics.

| Characteristic | No. (%) (N = 51) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 43 (84) |

| Female | 8 (16) |

| Age, median (range), y | |

| At time of transplantation | 51 (19-71) |

| At diagnosis of aggressive SCC | 62 (36-77) |

| Transplanted organ | |

| Kidney | 40 (78) |

| Heart | 2 (4) |

| Liver | 1 (2) |

| Lung | 4 (8) |

| Kidney and pancreas | 3 (6) |

| Liver and lung | 1 (2) |

| Survival status at last follow-up | |

| Alive | 7 (14) |

| Death due to SCC | 32 (63) |

| Death due to other causes | 12 (24) |

Abbreviation: SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

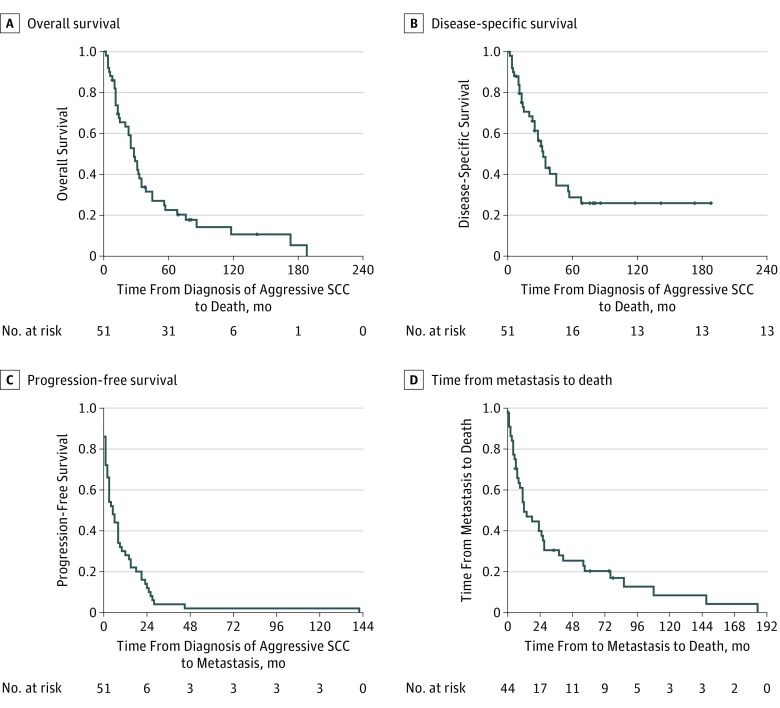

The most common primary site for SCC was the face (34 [67%]) (Table 2). The median diameter of aggressive SCC was 18.0 mm (range, 4.0-64.0 mm), with a median depth of invasion of 6.2 mm (range, 1.0-20.0 mm). A total of 21 tumors (41%) were histologically classified as poorly differentiated and perineural invasion was identified in 20 of the SCCs (39%). The local recurrence rate was 45% (n=23). Tumor characteristics are listed in detail in Table 2. The Figure shows overall survival, disease-specific survival, progression-free survival, and time from metastasis to death overall by Kaplan-Meier analysis. Figure, A shows that 50% overall survival was reached at 28.0 months (95% CI, 21.3-34.7 months) and mean (SD) 5-year overall survival was 23.0% (6.4%), while mean (SD) 10-year survival was 11.3% (5.5%). Figure, B shows that 50% disease-specific survival was reached at 33.0 months (95% CI, 0.9-45.1 months) and mean (SD) 5-year disease-specific survival was 30.5% (7.6%), while mean (SD) 10-year survival was 25.9% (7.1%). Figure, C shows that mean (SD) 5-year and 10-year progression-free survival were 5.0% (1.3%) (95% CI, 2.5-7.3 years). Median time from metastasis to death was 12.0 months (95% CI, 3.8-20.2 months) (Figure, D). Almost all SCCs showed progression within 2 years from diagnosis.

Table 2. Tumor Characteristics.

| Characteristic | No. (%) (N = 51) |

|---|---|

| Location of aggressive SCCa | |

| Scalp | 6 (12) |

| Face | 34 (67) |

| Neck | 1 (2) |

| Trunk | 2 (4) |

| Arm or hand | 6 (12) |

| Genitalia | 2 (4) |

| Histologic classification of SCC | |

| Well differentiated | 10 (20) |

| Moderately differentiated | 15 (29) |

| Poorly differentiated | 21 (41) |

| Spindle cell morphologic characteristics | 2 (4) |

| Desmoplastic | 3 (6) |

| Primary tumor, median (range), mm | |

| Diameter of SCC | 18.0 (4-64) |

| Total No. (No. missing) | 50 (1) |

| Depth of invasion | 6.2 (1-20) |

| Total No. (missing) | 48 (3) |

| Tumor-free margins on histologic examination | 2.0 (0-15) |

| Total No. (No. missing) | 38 (13) |

| Clark level of invasionb | |

| Level I | 1 (2) |

| Level II | 1 (2) |

| Level III | 0 |

| Level IV | 14 (28) |

| Level V | 33 (65) |

| Missing data | 2 (4) |

| Perineural invasion | |

| Absent | 30 (59) |

| Present | 20 (39) |

| Missing data | 1 (2) |

| Local recurrence | |

| Absent | 21 (41) |

| Present | 23 (45) |

| Missing data | 7 (14) |

| Metastasis sitec | |

| No metastasis | 6 (12) |

| Lymph nodes | 30 (59) |

| Parotid gland | 10 (20) |

| Liver | 2 (4) |

| Lung | 6 (12) |

| Brain | 4 (8) |

| Bone | 7 (14) |

| Skin | 11 (22) |

| Muscle | 1 (2) |

| Intraorbital | 1 (2) |

Abbreviation: SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

An aggressive SCC was defined by regional metastasis (lymph nodes or parotid gland); distant metastasis including liver, lung, brain, or bone; or a local, therapy-resistant progression of primary SCC.

Clark level I is confined to the epidermis, level II penetrates the papillary dermis, level III fills the papillary dermis, level IV extends into reticular dermis, and level V invades subcutis.

Metastasis location was counted for every patient; some had multiple organ metastasis.

Figure. Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC) Overall Survival, Disease-Specific Survival, Progression-Free Survival, and Time From Metastasis to Death.

A, An overall survival of 50% was reached at 28.0 months (95% CI, 21.3-34.7 months). Mean (SD) 5-year overall survival was 23.0% (6.4%), while mean (SD) 10-year overall survival was 11.3% (5.5%). B, A disease-specific survival of 50% disease-specific survival was reached at 33.0 months (95% CI, 0.9-45.1 months). Mean (SD) 5-year disease-specific survival was 30.5% (7.6%) and mean (SD) 10-year disease-specific survival was 25.9% (7.1%). C, Mean (SD) 5- and 10-year progression-free survival were 5% (1.3%) (95% CI, 2.5-7.3 years). D, Median time from metastasis to death was 12 months (95% CI, 3.8-20.2 months). Tick marks indicate censoring.

Discussion

Patient Characteristics

Most of our solid organ transplant recipients were male, with a median age of 51 years at the time of transplantation and median age of 62 years at diagnosis of aggressive SCC. This finding is in agreement with those of Pinho et al,29 who reported on keratinocyte carcinoma, with a median patient age of 54.5 years at transplantation and 61.9 years at diagnosis of aggressive SCC. In contrast to our data, there was no difference in terms of sex in their study. In a study by Lott et al,22 SCC in solid organ transplant recipients occurred earlier, at a median age of 57 years, compared with immunocompetent patients, who developed SCC at a median age of 67 years.22 Although our case series was not selected in a randomized fashion, our patient characteristics suggest that our series is typical for solid organ transplant recipients.

Tumor Characteristics

The body site for aggressive SCC in our study was preferentially on the face and scalp, followed by the upper extremities. Rabinovics et al30 similarly report a high number of SCC in the head and neck region, with a 24% incidence of aggressive (local recurrence, nodal, or distant metastasis) head and neck SCC in solid organ transplant recipients, compared with other aggressive malignant neoplasms occurring on the head and neck. Pinho et al29 found keratinocyte cancer on UV-exposed sites for 83% of SCCs and 87% of basal cell carcinomas.

Most tumors in our series were poorly or moderately differentiated. The presence of poor differentiation indicates a poorer prognosis. Brantsch et al13 demonstrate a 3-fold higher risk for local recurrence and a 2-fold higher risk for metastasis compared with well-differentiated SCCs. Mullen et al31 demonstrate a 2.9-fold higher risk of metastasis or death in poorly differentiated tumors compared with well-differentiated or moderately differentiated tumors.

The median tumor diameter in our study was 18 mm (range, 4-64 mm). This diameter is slightly smaller than a Swedish cohort in which aggressive SCCs were 20 mm in diameter or larger.32 Based on a meta-analysis by Thompson et al,33 tumor diameter larger than 2 cm is the risk factor most highly associated with disease-specific death and a 19-fold higher risk of death from SCC compared with tumors with a diameter less than 2 cm.

The median tumor thickness in our study population was 6.2 mm. This risk factor is highly associated with recurrence and metastasis, with tumor thickness greater than 2 mm having a 10-fold higher risk of local recurrence and 11-fold higher risk of metastasis.33 In a prospective study by Breuninger et al,34 tumor depth greater than 4 mm was linked to a metastasis rate of 9%, increasing to a metastasis rate of 16% for a tumor thickness of 6 mm or more.

Perineural invasion (39%) and local recurrence (45%) were frequent in our study, but will have been selected for in a cohort of patients with aggressive SCC. In the general population, perineural invasion is rare, with an incidence of 2.5% to 5.0% for primary SCCs, and is associated with a 4-fold to 5-fold increased risk of nodal metastasis and death due to SCC.35 Local recurrence is reported to occur in 7% to 16% of all patients with SCC and is more frequent when there is perineural invasion.30,36

The most common location of metastasis in the solid organ transplant recipients in our study was the lymph nodes, including the parotid gland and skin. Lindelöf et al32 demonstrated that all lethal SCCs (7 of 544 SCCs in a cohort of 5931 solid organ transplant recipients) were located on the head, and that the parotid gland was the principal site for metastasis. A retrospective study by Lott et al22 found a 3.5 higher risk for solid organ transplant recipients to develop lymph node metastasis compared with the tumors in the immunocompetent control group.

Survival

Our study demonstrated a poor prognosis of aggressive SCC, with a 5-year overall survival rate of 23% and a 5-year disease-specific survival rate of 30.5%. Rabinovics et al30 showed a 5-year survival rate of 67.7% and 10-year survival rate of 40.0% in patients with SCC; however, that study included nonaggressive SCC. Lott et al22 reported a 3-year disease-specific survival rate of 56% for metastatic SCC in solid organ transplant recipients. A study by Mullen et al31 showed a 5-year overall survival rate of 35% and a 5-year disease-specific survival rate of 50% in patients with aggressive SCC of the trunk or extremities. In summary, our case series in solid organ transplant recipients shows an unfavorable survival for those with primary SCC with aggressive features, comparable with that seen in other reports.

Limitations

This study is limited by its retrospective design, the limited number of patients, and number of contributing centers. There is an implict bias in selecting tumors with a poor outcome (ie, recurrence, metastasis, and death) toward clinical and pathologic factors known to be associated with poor outcomes, such as perineural invasion. Another limitation is the lack of a control group (solid organ transplant recipients without development of aggressive SCC). Data on ethnicity, skin type, and sun exposure were not available.

Conclusions

Taken together, our case series confirms that anatomical site, differentiation, tumor diameter, tumor depth, and perineural invasion are important risk factors in aggressive SCC in solid organ transplant recipients. We also demonstrated a poor prognosis of aggressive SCC.

References

- 1.Harwood CA, Toland AE, Proby CM, et al. ; KeraCon Consortium . The pathogenesis of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in organ transplant recipients. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177(5):1217-1224. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Harris AR, et al. . Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer in the United States, 2006. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146(3):283-287. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paolino G, Donati M, Didona D, Mercuri SR, Cantisani C. Histology of non-melanoma skin cancers: an update. Biomedicines. 2017;5(4):71. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines5040071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lai V, Cranwell W, Sinclair R. Epidemiology of skin cancer in the mature patient. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36(2):167-176. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2017.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rangwala S, Tsai KY. Roles of the immune system in skin cancer. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165(5):953-965. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10507.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Euvrard S, Kanitakis J, Claudy A. Skin cancers after organ transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(17):1681-1691. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Veness MJ, Quinn DI, Ong CS, et al. . Aggressive cutaneous malignancies following cardiothoracic transplantation: the Australian experience. Cancer. 1999;85(8):1758-1764. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krynitz B, Edgren G, Lindelöf B, et al. . Risk of skin cancer and other malignancies in kidney, liver, heart and lung transplant recipients 1970 to 2008—a Swedish population-based study. Int J Cancer. 2013;132(6):1429-1438. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harwood CA, Proby CM, McGregor JM, Sheaff MT, Leigh IM, Cerio R. Clinicopathologic features of skin cancer in organ transplant recipients: a retrospective case-control series. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(2):290-300. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.10.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Madeleine MM, Patel NS, Plasmeijer EI, et al. ; the Keratinocyte Carcinoma Consortium (KeraCon) Immunosuppression Working Group . Epidemiology of keratinocyte carcinomas after organ transplantation. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177(5):1208-1216. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rizvi SMH, Aagnes B, Holdaas H, et al. . Long-term change in the risk of skin cancer after organ transplantation: a population-based nationwide cohort study. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(12):1270-1277. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.2984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmults CD, Karia PS, Carter JB, Han J, Qureshi AA. Factors predictive of recurrence and death from cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a 10-year, single-institution cohort study. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149(5):541-547. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.2139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brantsch KD, Meisner C, Schönfisch B, et al. . Analysis of risk factors determining prognosis of cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma: a prospective study. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(8):713-720. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70178-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brougham ND, Dennett ER, Cameron R, Tan ST. The incidence of metastasis from cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and the impact of its risk factors. J Surg Oncol. 2012;106(7):811-815. doi: 10.1002/jso.23155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karia PS, Han J, Schmults CD. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: estimated incidence of disease, nodal metastasis, and deaths from disease in the United States, 2012. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68(6):957-966. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.11.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lechler RI, Sykes M, Thomson AW, Turka LA. Organ transplantation—how much of the promise has been realized? Nat Med. 2005;11(6):605-613. doi: 10.1038/nm1251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muehleisen B, Jiang SB, Gladsjo JA, Gerber M, Hata T, Gallo RL. Distinct innate immune gene expression profiles in non-melanoma skin cancer of immunocompetent and immunosuppressed patients. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e40754. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wheless L, Jacks S, Mooneyham Potter KA, Leach BC, Cook J. Skin cancer in organ transplant recipients: more than the immune system. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(2):359-365. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.02.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harwood CA, Mesher D, McGregor JM, et al. . A surveillance model for skin cancer in organ transplant recipients: a 22-year prospective study in an ethnically diverse population. Am J Transplant. 2013;13(1):119-129. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04292.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Reilly Zwald F, Brown M. Skin cancer in solid organ transplant recipients: advances in therapy and management, part I: epidemiology of skin cancer in solid organ transplant recipients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(2):253-261. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.11.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Collett D, Mumford L, Banner NR, Neuberger J, Watson C. Comparison of the incidence of malignancy in recipients of different types of organ: a UK registry audit. Am J Transplant. 2010;10(8):1889-1896. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03181.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lott DG, Manz R, Koch C, Lorenz RR. Aggressive behavior of nonmelanotic skin cancers in solid organ transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2010;90(6):683-687. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181ec7228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martinez JC, Otley CC, Stasko T, et al. ; Transplant-Skin Cancer Collaborative . Defining the clinical course of metastatic skin cancer in organ transplant recipients: a multicenter collaborative study. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139(3):301-306. doi: 10.1001/archderm.139.3.301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bouwes Bavinck JN, Euvrard S, Naldi L, et al. ; EPI-HPV-UV-CA group . Keratotic skin lesions and other risk factors are associated with skin cancer in organ-transplant recipients: a case-control study in the Netherlands, United Kingdom, Germany, France, and Italy. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127(7):1647-1656. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramsay HM, Fryer AA, Hawley CM, Smith AG, Nicol DL, Harden PN. Factors associated with nonmelanoma skin cancer following renal transplantation in Queensland, Australia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(3):397-406. doi: 10.1067/S0190-9622(03)00902-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jensen AO, Svaerke C, Farkas D, Pedersen L, Kragballe K, Sørensen HT. Skin cancer risk among solid organ recipients: a nationwide cohort study in Denmark. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90(5):474-479. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodríguez-Acosta ED, Calva-Mercado JJ, Alberú-Gómez J, Vilatoba-Chapa M, Domínguez-Cherit J. Patients with solid organ transplantation and skin cancer: determination of risk factors with emphasis in photoexposure and immunosuppressive regimen: experience in a third level hospital [in Spanish]. Gac Med Mex. 2015;151(1):20-26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perez HC, Benavides X, Perez JS, et al. . Basic aspects of the pathogenesis and prevention of non-melanoma skin cancer in solid organ transplant recipients: a review. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56(4):370-378. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pinho A, Gouveia M, Cardoso JC, Xavier MM, Vieira R, Alves R. Non-melanoma skin cancer in Portuguese kidney transplant recipients—incidence and risk factors. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91(4):455-462. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20164891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rabinovics N, Mizrachi A, Hadar T, et al. . Cancer of the head and neck region in solid organ transplant recipients. Head Neck. 2014;36(2):181-186. doi: 10.1002/hed.23283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mullen JT, Feng L, Xing Y, et al. . Invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the skin: defining a high-risk group. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13(7):902-909. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2006.07.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lindelöf B, Jarnvik J, Ternesten-Bratel A, Granath F, Hedblad MA. Mortality and clinicopathological features of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in organ transplant recipients: a study of the Swedish cohort. Acta Derm Venereol. 2006;86(3):219-222. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thompson AK, Kelley BF, Prokop LJ, Murad MH, Baum CL. Risk factors for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma recurrence, metastasis, and disease-specific death: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152(4):419-428. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.4994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Breuninger H, Brantsch K, Eigentler T, Häfner HM. Comparison and evaluation of the current staging of cutaneous carcinomas. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2012;10(8):579-586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carter JB, Johnson MM, Chua TL, Karia PS, Schmults CD. Outcomes of primary cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma with perineural invasion: an 11-year cohort study. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149(1):35-41. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Que SKT, Zwald FO, Schmults CD. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: incidence, risk factors, diagnosis, and staging. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(2):237-247. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.08.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]