Abstract

This survey study examines changes in the use of marijuana by adolescents since legalization of recreational use in Washington State.

In November 2012, voters in Washington legalized nonmedical (retail) cannabis for people aged 21 and older. Markets opened in July 2014. The effect of this change on cannabis use among youths is of public health concern.

Cerdá et al1 analyzed data from the nationally representative Monitoring the Future survey (MTF) and used difference-in-differences methods to compare cannabis use prevalence trends among youths in Washington with use in states without legalization of recreational marijuana. Because the MTF is not designed to provide state-representative estimates, the article generated covariate-adjusted modeled prevalence estimates for each state. The article suggested complex association between legalization and cannabis use among youths: increases in prevalence among Washington 8th and 10th graders, but not among 12th graders, relative to use in states without legalization of recreational marijuana.

The authors noted that, “the sample design may lead to discrepancies between MTF results and those found in other large-scale surveillance efforts.”1(p148) The purpose of the present study was to assess whether trends in cannabis use prevalence among youths from Washington’s state-based youth survey are consistent with findings from the MTF.

Methods

The Washington Healthy Youth Survey (HYS)2 is an anonymous, school-based survey of 8th, 10th, and 12th graders and the state’s primary source of information about health behavior among youths. The HYS has been implemented in the fall of even-numbered years since 2002, using a simple random sample of public schools to generate a state-representative sample. Response rates (incorporating school and student response) in 2016 were 80% for 8th grade, 69% for 10th grade, and 49% for 12th grade. The study was approved by the Washington State Institutional Review Board, whose general policy waives informed patient consent when data are deidentified.

We generated covariate-adjusted prevalence estimates, modeling as closely as possible to Cerdá et al.1 Prevalence was based on modeled estimates (ie, SUDAAN predMARG [RTI International] postestimation command). Because the postlegalization periods are not identical, we present HYS data from both 2014 alone and 2014-2016 combined (MTF reported 2013-2015). Significance was established at P < .05 with unpaired, 2-tailed testing. Analysis was conducted using Stata, version 14.2 (StataCorp).

Results

More schools and students are captured in the HYS than MTF (Table). The MTF included fewer low–socioeconomic status and nonwhite youth in the prelegalization vs postlegalization period.

Table. School-Based Survey Sample Characteristics and Responses, Washington State, 2010-2016.

| Sample | Healthy Youth Surveya | Monitoring the Future Surveyb | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010-2012 | 2014 | P Valuec | 2014-2016 | P Valuec | 2010-2012 | 2013-2015 | P Valued | |

| Schools, No. | 221 | 116 | 226 | 24 | 23 | |||

| Students, No. | 47 561 | 26 133 | 53 220 | 2912 | 2597 | |||

| Urban schools, % | 74.3 | 82.1 | .12 | 78.2 | .34 | 78.0 | 73.1 | <.001 |

| Student characteristics, % | ||||||||

| White non-Hispanic | 56.3 | 54.7 | .51 | 53.6 | .16 | 67.2 | 55.1 | <.001 |

| Low SESe | 14.0 | 12.8 | .38 | 14.4 | .75 | 8.9 | 13.3 | <.001 |

| Youth cannabis use, % (95% CI) | ||||||||

| All students | 19.4 (18.6-20.2) | 18.4 (17.3-19.6) | .28 | 17.9 (17.1-18.8) | .01 | 13.9 (12.8-15.3) | 14.5 (13.2-15.9) | NR |

| Grade 8 | 9.8 (9.1-10.5) | 8.0 (7.1-8.8) | .003 | 7.3 (6.6-8.0) | <.001 | 6.2 (4.4-8.7) | 8.2 (6.3-10.7) | .16 |

| Grade 10 | 19.8 (18.6-21.0) | 18.5 (16.9-20.1) | .25 | 17.8 (16.7-18.9) | .01 | 16.2 (14.0-18.6) | 20.3 (16.9-24.1) | .02 |

| Grade 12 | 26.6 (25.2-28.0) | 27.0 (24.8-29.2) | .72 | 26.7 (25.2-28.3) | .91 | 21.2 (17.4-25.6) | 21.8 (18.0-26.1) | .83 |

Abbreviations: NR, not reported; SES, socioeconomic status.

Healthy Youth Survey cannabis use prevalence based on modeled estimates (Stata software margins postestimation command). The 2010-2012 cannabis use estimates are from models with 2014-2016 data. Student characteristics weighted by grade and year.

Data obtained from Cerdá et al.1 Prevalence was based on modeled estimates (ie, SUDAAN predMARG [RTI International Inc] postestimation command); number of students by grade was not reported. The 95% CIs for all grade cannabis use were added using z scores.

P values from χ2 tests for school and student characteristics, and from logistic regression for youth cannabis use by period (eg, either 2014 or 2014-2016 vs 2010-2012).

P values for school/student characteristics based on z scores for cannabis use.1

Low SES based on mother’s highest level of educational level less than high school graduate.

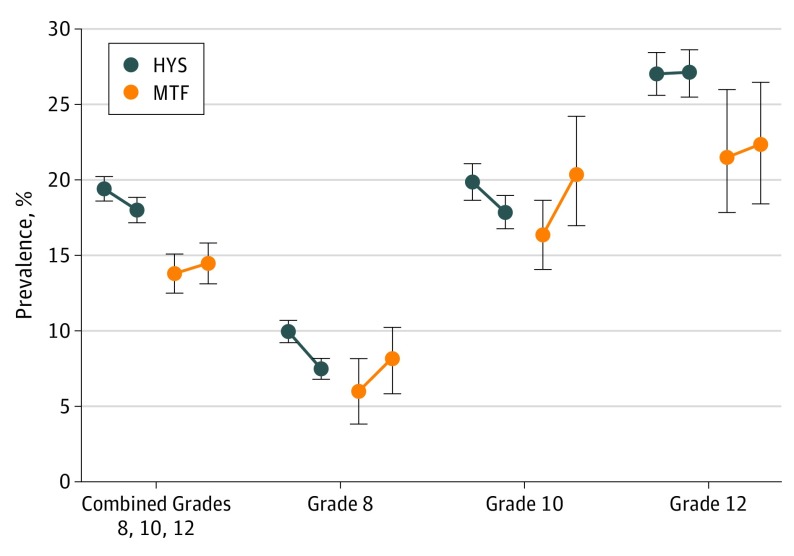

Estimates from the MTF show statistically nonsignificant change in the prevalence of cannabis use for 8th graders (from 6.2% [95% CI, 4.4%-8.7%] to 8.2% [95% CI, 6.3%-10.7%]; P = .16), and a significant increase for 10th graders (from 16.2% [95% CI, 14.0%-18.6%] to 20.3% [95% CI, 16.9%-24.1%]; P = .02). In contrast, the HYS shows statistically significant declines in prevalence from 2010-2012 to 2014-2016 among both 8th graders (from 9.8% [95% CI, 9.1%-10.5%] to 7.3% [95% CI, 6.6%-8.0%]; P < .001) and 10th graders (from 19.8% [95% CI, 18.6%-21.0%] to 17.8% [95% CI, 16.7%-18.9%]; P = .01). Neither MTF nor HYS analysis showed changes among 12th graders (Figure). Findings from HYS comparisons to 2014 alone were of less magnitude but similar direction.

Figure. Past-Month Cannabis Use Prevalence Among Washington State Youth by Survey and Grade Before and After Legalization.

Washington Healthy Youth Survey (HYS) modeled estimates in 2010-2012 and 2014-2016 and Monitoring the Future survey (MTF) in 2010-2012 and 2013-2015. Error bars indicate 95% CI.

Discussion

In contrast to Cerdá et al,1 Washington’s HYS data suggest that cannabis use among youths declined after legalization among 8th and 10th graders. The main difference is among 10th graders: the MTF suggests a statistically significant increase while HYS suggests a decrease.

These surveys have different purposes: the HYS provides results generalizable to youths in public schools statewide, while the MTF is designed to provide national and US regional (not state-specific) estimates. Hence, the MTF sample may be more influenced by unmeasured characteristics of Washington youths, especially if some subpopulations disproportionately captured are differently affected by legalization. For example, many Washington cities and counties have banned or restricted retail sales following state legalization,3 and differential exposure to local policy contexts may partially explain the varied patterns between the samples. Furthermore, there are differences in sampling error: the smaller MTF sample resulted in larger 95% CIs overlapping between prelegalization and postlegalization periods. In addition, the lack of an HYS comparison group limits the ability to make inferences about specific effects of cannabis legalization.

It is too soon to know the long-term influence that cannabis legalization will have on the prevalence of its use by youths. Further studies are needed with representative state samples, including subgroups; information about patterns of consumption rather than just prevalence; and attention to local implementation.

References

- 1.Cerdá M, Wall M, Feng T, et al. Association of state recreational marijuana laws with adolescent marijuana use. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(2):142-149. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.3624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Washington State Department of Social and Health Services, Department of Health, Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction, and Liquor and Cannabis Board Healthy Youth Survey 2016 Analytic Report, Olympia, WA. http://www.AskHYS.net. Published June 2017. Accessed April 30, 2018.

- 3.Dilley JA, Hitchcock L, McGroder N, Greto LA, Richardson SM. Community-level policy responses to state marijuana legalization in Washington State. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;42:102-108. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.02.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]