Abstract

This before-after study examines the association between value-based incentive programs that link financial rewards and penalties to hospital performance on quality indicators and catheter-associated urinary tract infection outcomes in intensive care units (ICUs).

Value-based incentive programs (VBIPs) aim to drive improvements in quality and reduce costs by linking financial incentives or penalties to hospital performance. Two VBIPs, the Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (VBP) Program and the Hospital-Acquired Condition Reduction Program (HACRP), target health care–associated infections reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Healthcare Safety Network. We evaluated the association between these VBIPs and catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs) in the critical care setting.

Methods

An interrupted time series design was used to examine the association between VBIPs and 3 CAUTI-related quality measures: device-associated infection rates (CAUTIs per 1000 indwelling urinary catheter–days), population-based infection rates (CAUTIs per 1000 patient-days), and indwelling urinary catheter device use (catheter-days per patient-days). We used National Healthcare Safety Network data from 2013 to 2017 for adults in nonfederal acute care hospitals that were subject to the inpatient prospective payment system and therefore eligible for HACRP and Hospital VBP Program incentives and penalties.1 We focused on intensive care units (ICUs) because CAUTI surveillance was not mandated for non-ICUs until 2015 and VBIPs did not target non-ICU CAUTIs until fiscal year 2018. Using patient-level case reports, we calculated unit-level CAUTI rates that included only cases associated with urine cultures growing at least 100 000 colony-forming units of bacteria per milliliter, and excluded cases associated with nonbacterial organisms or lower-growth bacteria, per the January 2015 National Healthcare Safety Network surveillance case definition revision.2 Hospital characteristics were collected from the 2015 American Hospital Association (AHA) annual survey.

We used generalized estimating equations with robust sandwich variance estimators to fit negative binomial models for infection rates and logistic regression models for device use to assess for changes in level and trend after VBIP implementation, accounting for hospital-level and unit-level clustering. Models included time, a post-VBIP implementation indicator (after October 1, 2015), and a 2-way interaction term with an a priori–defined VBIP implementation roll-in period (October 1, 2014–September 30, 2015) to account for the lag between the onset of the HACRP and the Hospital VBP Program payment adjustments. We considered 2-sided P<.05 to be statistically significant and used SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute) for all analyses. The Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute Institutional Review Board approved this study with a waiver of informed consent.

Results

The sample included 592 hospitals from 49 states and the District of Columbia, contributing 22 572 494 patient-days and 13 607 240 indwelling urinary catheter-days from 1185 ICUs. Compared with the hospitals with intensive care services subject to the inpatient prospective payment system included in the 2015 AHA annual survey, study hospitals were larger (≥400 beds) teaching hospitals located in the Northeast and in metropolitan areas (Table).

Table. Characteristics of Acute Care Hospitals With Critical Care Services Included in the 2015 American Hospital Association (AHA) Annual Survey and Study Hospitals Reporting Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infection (CAUTI) Measures .

| Hospital Characteristic, No. (%)a | AHA (n = 3076)b | Study (n = 592) |

|---|---|---|

| Region | ||

| Midwest | 704 (23) | 110 (19) |

| Northeast | 506 (16) | 169 (29) |

| South | 1281 (42) | 214 (36) |

| West | 585 (19) | 99 (17) |

| Location | ||

| Metropolitan | 2400 (78) | 511 (86) |

| Suburban | 506 (16) | 65 (11) |

| Rural | 170 (6) | 16 (3) |

| Bed size | ||

| <100 | 873 (28) | 88 (15) |

| 100-399 | 1749 (57) | 358 (60) |

| ≥400 | 454 (15) | 146 (25) |

| Type of ownership | ||

| For-profit | 694 (23) | 189 (32) |

| Not-for-profit | 1972 (64) | 360 (61) |

| Public | 410 (13) | 43 (7) |

| Teaching statusc | ||

| Graduate | 986 (32) | 227 (38) |

| Major | 245 (8) | 91 (15) |

| Minor | 194 (6) | 26 (4) |

| Nonteaching | 1651 (54) | 248 (42) |

| Full-time equivalent nurses, median (IQR) No. per 100 patient-days | 0.80 (0.6-1.1) | 0.78 (0.6-1.0) |

| Inpatient days covered by Medicare, median % (IQR) | 52 (45-62) | 49 (44-58) |

| Inpatient days covered by Medicaid, median % (IQR) | 19 (12-25) | 21 (14-25) |

Data on hospital characteristics are from the 2015 AHA annual survey. Data are presented as No. (%) unless otherwise noted.

AHA hospitals were limited to acute care hospitals subject to the inpatient prospective payment system and that indicated the availability of intensive care services in response to the 2015 AHA annual survey.

All hospitals were placed into 1 of 4 categories based on their response to the AHA survey: major teaching hospitals (hospitals that are members of the Council of Teaching Hospitals [COTH]), graduate teaching hospitals (hospitals that are not COTH members with a residency training program approved by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education), minor teaching hospitals (hospitals that are not COTH members with a medical school affiliation reported to the American Medical Association), and nonteaching hospitals (all other institutions).

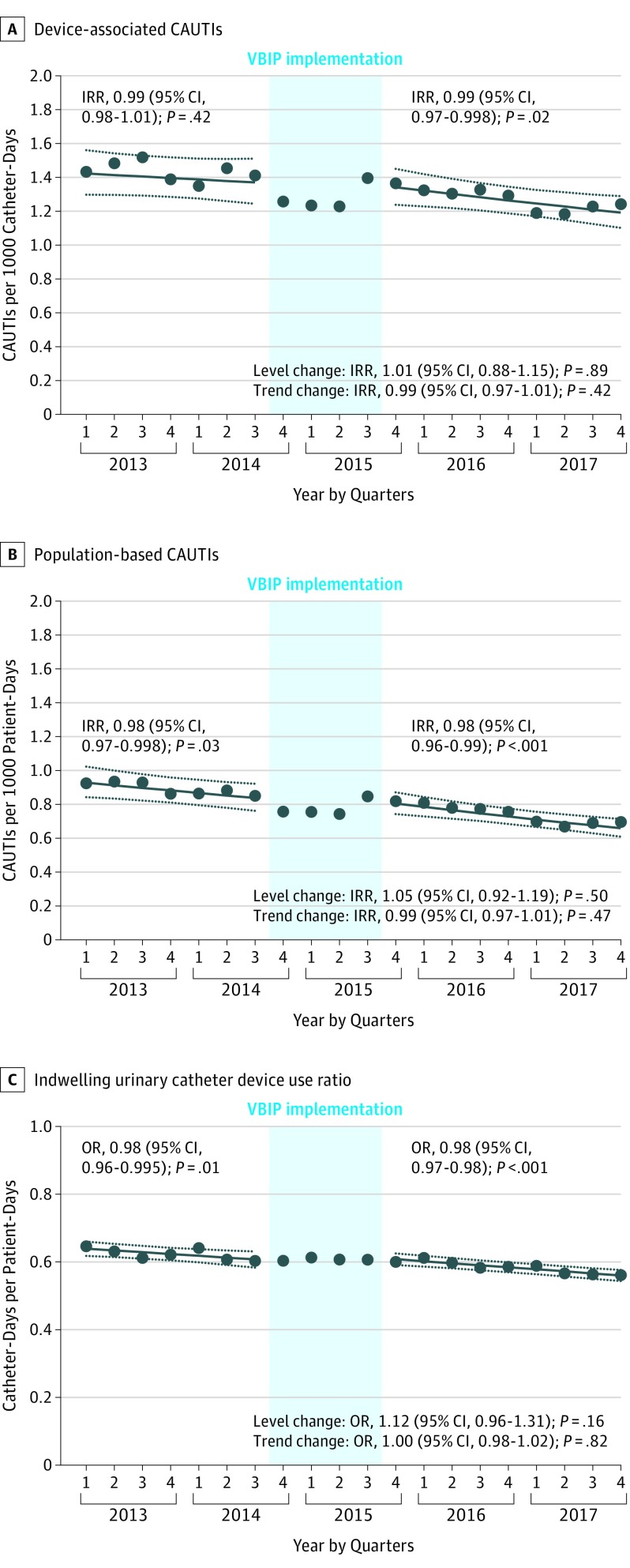

Value-based incentive program implementation was not significantly associated with immediate changes or changes in trend for any outcome (Figure). The device-associated CAUTI rate was stable before VBIP implementation and significantly declined by 1% per quarter after implementation, but the change in slope was not significant. Population-based rates and device use declined significantly by 2% per quarter before and after implementation, without significant changes in slope.

Figure. Effect of Value-Based Incentive Program (VBIP) Implementation on Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infection (CAUTI) Outcomes.

Observed and predicted rates of CAUTI-related quality measures aggregated for all study hospitals by quarter. Circles depict observed CAUTIs in panels A and B and observed device use in panel C. Solid lines represent model-predicted outcomes and dotted lines represent 95% CIs. Incident rate ratios (IRRs) or odds ratios (ORs) are reported for pre-VBIP and post-VBIP implementation trends, and ratios of IRRs or ORs are reported for post-VBIP vs pre-VBIP level change and change in trend.

Discussion

Federal VBIPs were not associated with reductions in device-associated CAUTI rates, the outcome incorporated into the VBIP scoring on which hospitals are graded. Value-based incentive program implementation was also not associated with changes in already declining population-based CAUTI rates or device use, measures that may more directly reflect CAUTI prevention efforts to decrease indwelling urinary catheter use.3

Study limitations include the primary focus on ICUs, although VBIPs did not explicitly target CAUTIs in non-ICUs until 2018. Limitations also include the need to confine analyses to a single health care–associated infection because revisions in surveillance case definitions and procedures for additional outcomes could not definitively be accounted for.

This study’s negative findings may reflect the priority placed on CAUTI prevention in the decade preceding VBIP implementation.4,5,6 In addition, VBIPs target numerous process, outcome, patient satisfaction, and composite measures, potentially limiting the ability to detect a significant population-level improvement in a single outcome. Nonetheless, the findings call into question the effectiveness of VBIPs for catalyzing improvements in care quality and underscore the importance of ongoing rigorous policy evaluations.

Section Editor: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor.

References

- 1.Preventing avoidable infectious complications by adjusting payment PAICAP Project website. http://www.paicap.org/index.html. Accessed September 27, 2018.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. NHSN HAI surveillance changes for 2015. National Healthcare Safety Network e-News. 2014;9(3):4-11. https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/newsletters/vol9-3-eNL-Sept-2014.pdf.

- 3.Fakih MG, Gould CV, Trautner BW, et al. Beyond infection: device utilization ratio as a performance measure for urinary catheter harm. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37(3):327-333. doi: 10.1017/ice.2015.287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Joint Commission The Joint Commission’s 2012 National Patient Safety Goals. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: The Joint Commission; 2012. http://www.jcrinc.com/assets/1/14/ebmnpsg12_sample_pages.pdf. Accessed September 27, 2018.

- 5.Department of Health and Human Services National Action Plan to Prevent Health Care-Associated Infections: Road Map to Elimination Washington, DC: Dept of Health and Human Services; 2009. https://health.gov/hcq/prevent-hai-action-plan.asp.

- 6.Saint S, Greene MT, Krein SL, et al. A program to prevent catheter-associated urinary tract infection in acute care. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(22):2111-2119. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]