Key Points

Question

What are the associations of opioid use disorder (OUD) with outcomes of cardiovascular surgery?

Findings

In this US nationwide cohort study of 5 718 552 cardiac surgery patients, compared with patients without OUD, there was no significant difference in mortality among patients with OUD, although they had a higher number of complications overall (67.6% vs 59.2%).

Meaning

Cardiac surgery in patients with OUD is safe, but it is associated with higher complications and resource utilization.

This cohort study characterizes the national population of cardiac surgery patients with opioid use disorder and compares outcomes with cardiac surgery patients without opioid use disorder.

Abstract

Importance

Persistent opioid use is currently a major health care crisis. There is a lack of knowledge regarding its prevalence and effect among patients undergoing cardiac surgery.

Objective

To characterize the national population of cardiac surgery patients with opioid use disorder (OUD) and compare outcomes with the cardiac surgery population without OUD.

Design, Setting, and Participants

In this retrospective population-based cohort study, more than 5.7 million adult patients who underwent cardiac surgery (ie, coronary artery bypass graft, valve surgery, or aortic surgery) in the United States were included. Pregnant patients were excluded. Propensity matching was performed to compare outcomes between cardiac surgery patients with OUD (n = 11 359) and without OUD (n = 5 707 193). The Nationwide Inpatient Sample database was queried from January 1998 to December 2013. Data were analyzed in January 2018.

Exposures

Persistent opioid use and/or dependence.

Main Outcomes and Measures

In-hospital mortality, complications, length of stay, costs, and discharge disposition.

Results

Among the 5 718 552 included patients, 3 887 097 (68.0%) were male; the mean (SD) age of patients with OUD was 47.67 (13.03) years and of patients without OUD was 65.53 (26.14) years. The prevalence of OUD among cardiac surgery patients was 0.2% (n = 11 359), with an 8-fold increase over 15 years (0.06% [262 of 437 641] in 1998 vs 0.54% [1425 of 263 930] in 2013; difference, 0.48%; 95% CI of difference, 0.45-0.51; P < .001). Compared with patients without OUD, patients with OUD were younger (mean [SD] age, 48 [0.30] years vs 66 [0.05] years; P < .001) and more often male (70.8% vs 68.0%; P < .001), black (13.7% vs 4.8%), or Hispanic (9.1% vs 4.8%). Patients with OUD more commonly fell in the first quartile of median income (30.7% vs 17.1%; P < .001) and were more likely to be uninsured or Medicaid beneficiaries (48.6% vs 7.7%; P < .001). Valve and aortic operations were more commonly performed among patients with OUD (49.8% vs 16.4%; P < .001). Among propensity-matched pairs, the mortality was similar between patients with vs without OUD (3.1% vs 4.0%; P = .12), but cardiac surgery patients with OUD had an overall higher incidence of major complications (67.6% vs 59.2%; P < .001). Specifically, the risks of blood transfusion (30.4% vs 25.9%; P = .002), pulmonary embolism (7.3% vs 3.8%; P < .001), mechanical ventilation (18.4% vs 15.7%; P = .02), and prolonged postoperative pain (2.0% vs 1.2%; P = .048) were significantly higher. Patients with OUD also had a significantly longer length of stay (median [SE], 11 [0.30] vs 10 [0.22] days; P < .001) and cost significantly more per patient (median [SE], $49 790 [1059] vs $45 216 [732]; P < .001).

Conclusions and Relevance

The population of patients with persistent opioid use or opioid dependency undergoing cardiac surgery has increased over the past decade. Cardiac surgery in patients with OUD is safe but is associated with higher complications and cost. Patients should not be denied surgery because of OUD status but should be carefully monitored postoperatively for complications.

Introduction

The opioid epidemic is a leading public health concern in the United States. An estimated 2 million individuals in the United States experience opioid use disorder (OUD), accruing annual costs of approximately $78.5 billion.1,2,3 The prevalence of OUD and associated burden of mortality have increased at an alarming rate over the past 15 years.4,5 Opioid-related overdoses accounted for nearly 33 100 deaths in 2015 alone, half of which were associated with prescription opioids.1,2,3

Prolonged opioid use has been associated with cardiovascular risk, although the mechanism of opioids in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease is unclear. A few reports have correlated coronary heart disease, myocardial infarction, poor post–myocardial infarction perfusion, and cardiovascular death with persistent opioid use.6,7,8 The contribution of infectious endocarditis (IE) to mortality among the population of intravenous drugs users (IVDUs) is well established in this population, accounting for 5% to 10% of deaths.9,10,11 Despite all this, data regarding the prevalence and outcomes of cardiovascular operations in this population are limited.

To our knowledge, most recent studies have focused on the negative outcomes from prescription opioid overdose and persistent use that occur postoperatively.12,13,14 However, because preoperative persistent opioid use is a risk factor for postoperative overdose and because nonphysician/illicit sources (the third highest provider of opioids) may equally have a negative effect on surgical outcomes, it is important for the effects of preoperative opioid misuse to be investigated.15,16

Studies investigating the association of OUD with surgical outcomes are limited. In particular, data regarding the outcomes of cardiovascular operations in this population are restricted mainly to reports based on single-institution experiences only.10,17,18,19,20,21 As such, a population-based overview of surgical outcomes among patients with OUD after various cardiovascular operations has not been previously reported. Therefore, the aims of this study were to use data from a large national database to (1) characterize the population of cardiac surgery patients with OUD and (2) investigate the association of underlying OUD with outcomes and resource utilization after cardiovascular operations.

Methods

Data Source and Study Population

The Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database (managed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality) was queried from January 1998 through December 2013 for patients undergoing isolated coronary artery bypass graft (CABG), valve surgery, or aortic surgery or a combination of these using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification diagnosis and procedure codes. The NIS database is the largest all-payer inpatient discharge database, containing unweighted data from more than 7 million hospitalizations per year and weighted data from more than 35 million hospitalizations. Patients in this database represent a 20% stratified random sample of all discharges in a given year. Because the database contains publicly available deidentified data, this study did not require review from our institutional review board.

Clinical Classifications Software procedure codes 44, 43, and 52 were used to identify patients undergoing CABG, valve surgery, and aortic surgery, respectively.22 We defined a history of OUD with International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification codes, previously described by Menendez et al.23 This operative definition is consistent with that listed by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition).24,25 Patients without these diagnoses were used as a control group. Pregnant patients and patients younger than 18 years or older than 100 years were also excluded.

Outcomes

Patient-level variables included age, sex, race/ethnicity, insurance status, income level, admission status, and discharge disposition. Patient race/ethnicity was previously classified by the NIS database, not by the authors, and was collected for the identification of possible disparities among racial/ethnic groups. Primary outcomes included mortality, complications, length of stay, hospital charges (ie, amount billed to hospitals for services, excluding professional fees), cost (ie, charges adjusted for inflation using a cost-to-charge ratio created by the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project based on accounting reports from the US Centers of Medicare and Medicaid Services), and discharge outcomes. Complications included stroke, blood transfusion, wound infection, renal complication, cardiac complication, gastrointestinal tract complication, pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis, pneumonia, mechanical ventilation, prolonged postoperative pain, and sepsis.

Statistical Analysis

Means with standard deviations and medians with standard errors were calculated for all continuous outcomes, while frequency counts and percentages were calculated for categorical outcomes. Appropriate statistical tests were used for continuous (t test) and categorical (χ2 test) outcomes to compare unadjusted differences between patients with and without OUD.

Propensity matching was conducted to balance covariables between patients with and without OUD to determine outcomes independent of confounding factors. Propensity scores (ie, the conditional probability of having OUD) were estimated for each patient using a multivariable regression model. Opioid use disorder was the dependent variable and patient demographic characteristics, payer status, comorbidities, hospital characteristics, and procedure type were the independent variables. We used a 1:1 greedy matching algorithm with a caliper of 0.2-fold the standard deviation of the linear propensity score. The balance of the covariables before and after matching were assessed using standardized differences between those with and without OUD (eFigure in the Supplement).26 For all covariables, χ2 tests were performed before matching, and McNemar tests were used in the matched sample.

Comorbidities in the model described by Elixhauser et al27 for administrative databases were used for propensity matching. A detailed list of all comorbidities used can be found in Table 1. Although the Society of Thoracic Surgeons risk score has also been used for risk stratification, it was not the ideal model for this study since the very specific comorbidities it lists would not be readily available in a discharge-level database such as the NIS database.

Table 1. Preoperative Characteristics of Cardiac Surgery Patients According to Preoperative Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) Status.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| OUD (n = 11 359) | No OUD (n = 5 707 193) | ||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 48 (0.30) | 66 (0.05) | <.001 |

| Age group, y | <.001 | ||

| 18-44 | 4219 (37.1) | 255 946 (4.5) | |

| 45-54 | 3786 (33.1) | 756 876 (13.3) | |

| 55-64 | 2272 (20.0) | 1 442 431 (25.3) | |

| 65-74 | 891 (7.8) | 1 826 606 (32.0) | |

| 75-84 | 180 (1.6) | 1 281 422 (22.5) | |

| 85-99 | 11 (0.1) | 143 912 (2.5) | |

| Sex | .006 | ||

| Male | 8042 (70.8) | 3 879 055 (68.0) | |

| Female | 3317 (29.2) | 1 827 664 (32.0) | |

| Race/ethnicity | <.001 | ||

| White | 6367 (56.1) | 3 602 825 (63.1) | |

| Black | 1559 (13.7) | 274 541 (4.8) | |

| Hispanic | 1030 (9.1) | 275 946 (4.8) | |

| Other/missing | 2403 (21.2) | 1 553 882 (27.2) | |

| Insurance | <.001 | ||

| Medicare | 2634 (23.2) | 3 090 606 (54.2) | |

| Medicaid | 4161 (36.6) | 273 509 (4.8) | |

| Private | 2295 (20.2) | 2 006 009 (35.2) | |

| Uninsured | 1355 (11.9) | 164 033 (32.9) | |

| Other | 913 (8.0) | 173 035 (3.0) | |

| Median household income | <.001 | ||

| First quartile | 3482 (30.7) | 974 689 (17.1) | |

| Second quartile | 2720 (24.0) | 1 460 509 (25.6) | |

| Third quartile | 2506 (22.1) | 1 475 016 (25.8) | |

| Fourth quartile | 2288 (20.1) | 1 644 605 (28.8) | |

| Missing | 363 (3.2) | 152 374 (2.7) | |

| Admission status | <.001 | ||

| Elective | 2581 (22.7) | 2 032 449 (35.6) | |

| Urgent | 7269 (64.0) | 1 914 139 (33.5) | |

| Missing | 1509 (13.3) | 1 760 605 (30.9) | |

| Type of procedure | <.001 | ||

| CABG | 4846 (42.7) | 4 092 597 (71.7) | |

| Valve surgery | 5399 (47.5) | 861 212 (15.1) | |

| Aortic surgery | 253 (2.2) | 74 256 (1.3) | |

| Combination | 860 (7.6) | 679 128 (11.9) | |

| Elixhauser model risk score | <.001 | ||

| Low (≤5) | 8993 (79.2) | 4 114 006 (72.1) | |

| Medium (6-15) | 1973 (17.4) | 1 383 953 (24.3) | |

| High (>15) | 393 (3.5) | 209 234 (3.7) | |

| Hospital location and teaching status | <.001 | ||

| Rural | 172 (1.5) | 200 581 (3.5) | |

| Urban nonteaching | 2809 (24.7) | 1 940 007 (34.0) | |

| Urban teaching | 8353 (73.5) | 3 551 699 (62.2) | |

| Missing | 25 (0.2) | 14 906 (0.3) | |

| Hospital geographic region | <.001 | ||

| Northeast | 3296 (29.0) | 1 099 010 (19.3) | |

| Midwest | 2119 (18.7) | 1 394 146 (24.4) | |

| South | 3313 (29.2) | 2 270 368 (39.8) | |

| West | 2631 (23.2) | 943 668 (16.5) | |

| Hospital bed size | .16 | ||

| Small | 621 (5.5) | 318 751 (5.6) | |

| Medium | 1886 (16.6) | 1 075 602 (18.9) | |

| Large | 8825 (77.7) | 4 297 934 (75.3) | |

| Missing | 27 (0.2) | 14 906 (0.3) | |

| Hospital volume (cardiac surgeries/y) | <.001 | ||

| 1-199 | 3758 (33.1) | 1 161 097 (20.3) | |

| 200-699 | 5082 (44.7) | 2 801 937 (49.1) | |

| 700-1999 | 2395 (21.1) | 1 626 536 (28.5) | |

| ≥2000 | 124 (1.1) | 117 622 (2.1) | |

| Hospital ownership | <.001 | ||

| Government | 1559 (13.7) | 444 328 (7.8) | |

| Private, nonprofit | 8829 (77.7) | 4 563 997 (80.0) | |

| Private, investor owned | 870 (7.7) | 605 179 (10.6) | |

| Missing | 101 (0.9) | 93 689 (1.6) | |

| Comorbidities | |||

| AIDS | 116 (1.0) | 3562 (0.1) | <.001 |

| Alcohol use disorder | 1667 (14.7) | 116 842 (2.1) | <.001 |

| Arrhythmia | 3231 (28.4) | 1 767 906 (31.0) | .02 |

| Deficiency anemia | 2428 (21.4) | 731 434 (12.8) | <.001 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 226 (2.0) | 91 375 (1.6) | .16 |

| Blood loss anemia | 259 (2.3) | 66 815 (1.2) | <.001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 385 (3.4) | 72 706 (1.3) | <.001 |

| Chronic lung disease | 3002 (26.4) | 1 126 998 (19.8) | <.001 |

| Coagulopathy | 1875 (16.5) | 629 943 (11.0) | <.001 |

| Depression | 1530 (13.5) | 223 457 (3.9) | <.001 |

| Diabetes | 1663(14.6) | 1 482 188 (26.0) | <.001 |

| Endocarditis | 3651 (32.1) | 61 705 (1.1) | <.001 |

| Hypertension | 5046 (44.4) | 3 524 671 (61.8) | <.001 |

| Hypothyroidism | 435 (3.8) | 408 855 (7.2) | <.001 |

| Liver disease | 1650 (14.5) | 49 229 (0.9) | <.001 |

| Lymphoma | 38 (0.3) | 22 875 (0.4) | .57 |

| Fluid and electrolyte imbalance | 3430 (30.2) | 1 043 143 (18.3) | <.001 |

| Metastatic cancer | 10.86 (0.1) | 9429 (0.2) | .43 |

| Neurological disorders | 534 (4.7) | 145 129 (2.5) | <.001 |

| Obesity | 1038 (9.1) | 642 677 (11.3) | .001 |

| Paralysis | 242 (2.2) | 59 841 (1.1) | <.001 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1319 (11.6) | 672 064 (11.8) | .73 |

| Psychoses | 866 (7.6) | 69 219 (1.2) | <.001 |

| Pulmonary circulation disorders | 287 (2.5) | 12 564 (0.2) | <.001 |

| Renal failure | 853 (7.5) | 450 562 (7.9) | .45 |

| Solid tumor without metastasis | 88 (0.8) | 151 729 (2.7) | <.001 |

| Tobacco use | 4514 (39.7) | 757 756 (13.3) | <.001 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 20 (0.2) | 34 904 (0.6) | .006 |

| Valvular disease | 358 (3.2) | 42 204 (0.7) | <.001 |

| Weight loss | 850 (7.5) | 116 105 (2.0) | <.001 |

Abbreviation: CABG, coronary artery bypass graft.

After matching, we compared outcomes between patients with and without OUD using paired t tests for continuous outcomes (eg, costs and length of stay) and conditional logistic regression for categorical outcomes (eg, mortality and complications). All P values were 2-tailed, and P values less than .05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using the SAS System for Unix version 9.2 (SAS Institute).

Results

Demographic and Patient Characteristics

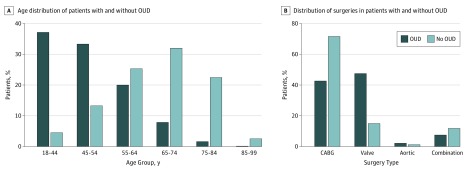

A total of 5 718 552 patients undergoing CABG, valve surgery, or aortic surgery between 1998 and 2013 were available from the NIS database. Among these, 11 359 patients (0.2%) met the criteria of OUD for analysis. Patients with OUD were younger than patients without OUD, with a mean (SD) age of 48 (0.30) years vs 66 (0.05) years (P < .001). Figure 1A depicts the age distribution of patients with OUD. The prevalence of OUD was much lower in older age groups (age 65 years or older: with OUD, 9.5% [1082 of 11 359]; without OUD, 57.0% [3 251 940 of 5 707 193]; P < .001).

Figure 1. Distribution of Age Group and Surgery Type Among Cardiac Surgery Patients With and Without Opioid Use Disorder (OUD).

Distribution of procedure type is shown in Figure 1B. Compared with patients without OUD, patients with OUD were much more likely to undergo valve surgery (47.5% [5399 of 11 359] vs 15.1% [861 212 of 5 707 193]; P < .001) or aortic surgery (2.2% [253 of 11 359] vs 1.3% [74 256 of 5 707 193]; P < .001) but less likely to undergo CABG (42.7% [4846 of 11 359] vs 71.7% [4 092 597 of 5 707 193]; P < .001) or a combination of these procedures (7.6% [860 of 11 359] vs 11.9% [679 128 of 5 707 193]; P < .001). Admission status was significantly more likely to be urgent in patients with OUD (64.0% [7269 of 11 359] vs 33.5% [1 914 139 of 5 707 193]; P < .001). Other patient-specific characteristics can be found in Table 1.

Trends

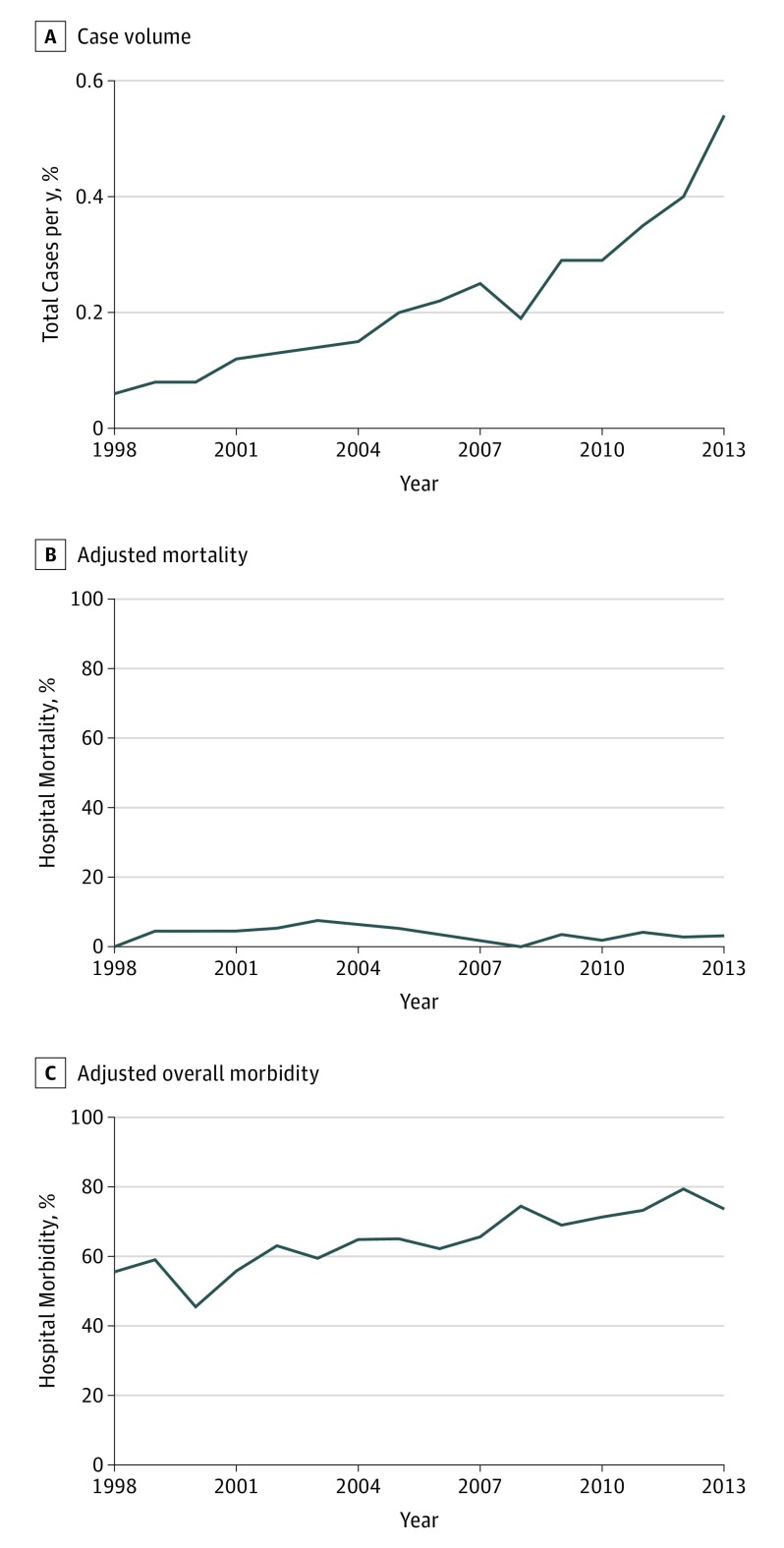

Trends in case volume, adjusted mortality, and adjusted overall morbidity are shown in Figure 2. From 1998 to 2013, the number of cardiac surgery patients with a history of OUD significantly increased 8-fold from 0.06% (262 of 437 641) of all annual cases to 0.54% (1425 of 263 930) (P < .001). Mortality rates did not significantly change from 1998 to 2013, but overall morbidity increased from 56% (146 of 262) to 74% (1050 of 1425) (P < .001).

Figure 2. Trends in Case Volume, Adjusted Mortality, and Adjusted Overall Morbidity Among Cardiac Surgery Patients With Opioid Use Disorder.

Outcomes

Unadjusted outcomes can be found in eTable 1 in the Supplement. Mortality among patients with OUD undergoing cardiac surgery compared with those without OUD did not differ (3.1% [357 of 11 359] vs 3.5% [198 954 of 5 707 193]; P = .38), but all unadjusted complications were significantly higher in patients with OUD, excluding wound infection and gastrointestinal tract complications.

Propensity matching resulted in 11 202 well-matched pairs (eFigure in the Supplement). Adjusted outcomes are displayed in Table 2. In patients with OUD compared with patients without, there was no difference in mortality (3.1% [352 of 11 202] vs 4.0% [450 of 11 237]; P = .12) but significantly increased risk of postoperative complications overall (67.6% [7576 of 11 202] vs 59.2% [6654 of 11 237]; P < .001). Preoperative OUD increased the risk for blood transfusion (30.4% [3405 of 11 202] vs 25.9% [2914 of 11 237]; P = .002), pulmonary embolism (7.3% [821 of 11 202] vs 3.8% [427 of 11 237]; P < .001), mechanical ventilation (18.4% [2065 of 11 202] vs 15.7% [1763 of 11 237]; P = .02), and prolonged postoperative pain (2.0% [221 of 11 202] vs 1.2% [133 of 11 237]; P = .048). There were no differences in postoperative stroke, pneumonia, sepsis, renal, gastrointestinal tract or cardiac complications, respiratory failure, deep vein thrombosis, or wound infection.

Table 2. Propensity-Matched Outcomes After Cardiac Surgery in Patients With and Without Opioid Use Disorder (OUD).

| Outcome | No. (%) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| OUD (n = 11 202) | No OUD (n = 11 237) | ||

| Hospital mortality | 352 (3.1) | 450 (4.0) | .12 |

| Complications | |||

| Any complication | 7576 (67.6) | 6654 (59.2) | <.001 |

| Stroke | 579 (5.2) | 544 (4.8) | .62 |

| Blood transfusion | 3405 (30.4) | 2914 (25.9) | .002 |

| Wound infection | 137 (1.2) | 163 (1.5) | .50 |

| Renal complication | 1890 (16.9) | 1733 (15.4) | .19 |

| Pneumonia | 1337 (11.9) | 1255 (11.2) | .42 |

| Cardiac complications | 1361 (12.2) | 1384 (12.3) | .87 |

| Respiratory failure | 1658 (14.8) | 1440 (12.8) | .05 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 821 (7.3) | 427 (3.8) | <.001 |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 190 (1.7) | 195 (1.7) | .92 |

| Ileus/gastrointestinal tract complications | 189 (1.7) | 163 (1.5) | .52 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 2065 (18.4) | 1763 (15.7) | .02 |

| Prolonged postoperative pain | 221 (2.0) | 133 (1.2) | .048 |

| Sepsis | 1842 (16.4) | 1687 (15.0) | .20 |

| Length of stay, median (SE) | 11 (0.30) | 10 (0.22) | <.001 |

| Total cost, median (SE), $ | 49 790 (1059) | 45 216 (732) | <.001 |

| Total charges, median (SE), $ | 133 601 (3599) | 121 705 (3812) | .01 |

| Discharge status | <.001 | ||

| Home | 4976 (44.4) | 5335 (47.5) | |

| Short-term skilled facility | 311 (2.8) | 276 (2.5) | |

| Long-term skilled facility | 2612 (23.3) | 1754 (15.6) | |

| Alive but status unknown | 10 (0.1) | 5 (0.04) | |

| Other | 3268 (29.2) | 3855 (34.3) | |

The median length of stay was significantly higher in patients with OUD, as was the median total cost. Patients with OUD were more likely to be discharged to a long-term skilled inpatient facility than to home (odds ratio [OR], 1.56; 95% CI, 1.47-1.72; P < .001).

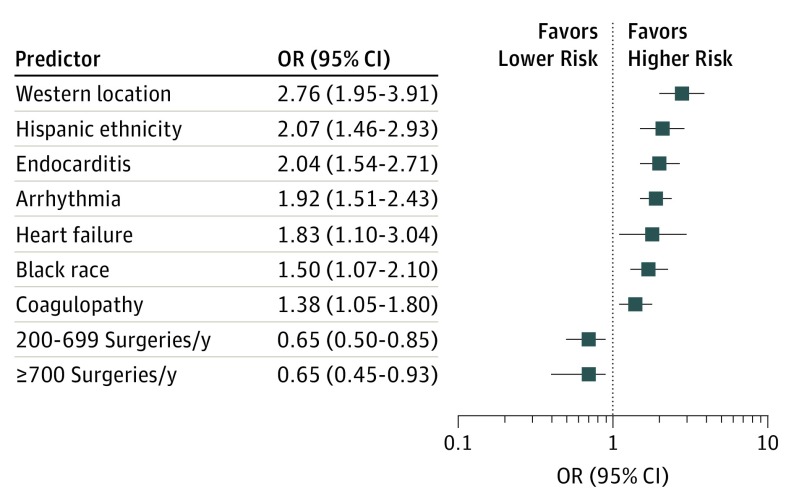

Risk of mortality (Figure 3) was increased among cardiac surgery patients with OUD who were black (OR, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.27-2.30; P = .02) or Hispanic (OR, 2.07; 95% CI, 1.46-2.93; P < .001). Arrhythmia (OR, 1.92; 95% CI, 1.51-2.43; P < .001), heart failure (OR, 1.83; 95% CI, 1.10-3.04; P = .02), coagulopathy (OR, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.05-1.80; P = .02), and endocarditis (OR, 2.04; 95% CI, 1.54-2.71; P < .001) also increased the likelihood of mortality in this group. Location in the West region was a significant predictor of mortality (OR, 2.76; 95% CI, 1.95-3.91; P < .001). Hospital volumes greater than 200 surgeries per year were protective against mortality (200-699 surgeries: OR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.45-0.93; 700-1000 surgeries: OR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.42-0.89). There were no mortalities for case volumes greater than 2000 cardiac surgeries per year.

Figure 3. Predictors of Mortality in Cardiovascular Surgery Patients With Opioid Use Disorder.

Error bars indicate 95% CIs.

Discussion

This analysis is, to our knowledge, the first to look at nationwide trends and outcomes in the population of all cardiac surgery patients with OUD. We have shown an 8-fold increase in cardiac patient volume per year between 1998 to 2013, no change in mortality rates, and a significant increase in morbidity. The trend in surgery volume aligns with a significant increase in persistent opioid use nationwide over the past decade. From 2004 to 2011, there was a 183% increase in opioid-related medical emergencies according to the Drug Abuse Warning Network.28 While persistent prescription opioid use rose substantially from 2002 to 2010, the rate of both prescriptions and opioid-related deaths from 2011 onward have decreased slightly.29 In our analysis, no such decrease in patient volume was seen from 2012 to 2013. This is likely because our reported patient volume includes patients using the illicit opioid heroin, the number of whom have only recently started to increase from 2010 to 2013.29 One study30 reports that between 2002 and 2012, the incidence of heroin initiation was 19-fold higher among those who reported previous nonmedical pain reliever use. Hence, the recent decrease in availability of prescription opioids because of concerted policy efforts have been offset by the rise in heroin use, leading to the rise of overall patients with OUD well into 2013.

Patients with OUD were more often distributed in hospitals in the Northeast and West regions, and location in the West region was a significant predictor of mortality. This is consistent with geographical distribution of disproportionately high rates of opioid prescription and persistent opioid use on California’s west coast.31 Other reports also support our finding that cardiac surgery patients with OUD are in line with the general OUD population in age (younger) and sex (male).32

Most patients with OUD in our analysis underwent either CABG (42.7%) or valve surgery (47.5%). The association of CABG outcomes with opiate use has been studied by mainly single-center studies in the Middle East, where opium use is prominent because of rumored cardioprotective effects. In a historical cohort study of 110 patients addicted to opium over 1.5 years, Nemati et al33 reported a significant increase in hemorrhage and blood transfusions after CABG, consistent with our findings. A prospective review of 56 opium-using patients conducted by Safaii and Kazemi17 reported no difference in mortality and comparable complication rates (pulmonary complications, 14.2%; blood transfusions, 33.3%), but complications did not significantly differ between opium users and nonusers. It is important to note that the population studied differs from ours in that opium use in the Middle East may not directly translate to the opioid-type drugs used in the United States. Our sample size was also much larger because of our population-based approach.

Although CABG and valve surgery were the most common procedures, we found that patients with OUD were less likely to undergo CABG than those without OUD despite evidence to suggest an increased risk of coronary and ischemic heart disease from persistent opioid use.6,7,8 This may be attributed to the younger age group and significantly lower prevalence of other major cardiovascular risk factors (eg, hypertension, diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, and obesity) in our sample. Cardiac surgery patients with OUD were more likely to have valve surgery or aortic surgery compared with those without OUD. Infectious endocarditis in the population of IVDUs is a well-established complication and may contribute to the increased number of valve procedures.9,10,11 A retrospective study of 29 IVDUs by Østerdal et al21 reported that 69% of these patients used opioids (ie, heroin, buprenorphine, and methadone hydrochloride). Staphylococcus aureus (52%) and Enterococcus faecalis (17%) infections were the primary causative agents in those requiring valve surgery. A total of 33 valves or rings were implanted (most often aortic valves), with a 30-day mortality of 7%. Five patients underwent a concurrent aortic root replacement, which may also help explain the higher rate of aortic surgery in our cohort.

A 2017 study11 also used the NIS database to examine 809 patients with OUD undergoing valve surgery owing to infectious endocarditis and reported significantly higher rates of pulmonary embolism and prolonged length of stay, but in contrast with our results, they also reported increased postoperative pneumonia (OR, 1.4), pulmonary embolism (OR, 1.9), infectious complications (OR, 1.5), and sepsis (OR, 1.4). We conducted a post hoc analysis excluding endocarditis from our propensity matching (eTable 2 in the Supplement). As a result, rates of pneumonia, sepsis, and renal complications became significantly higher among patients with OUD. Hence, it appears that OUD-related infectious endocarditis is the driving factor behind these specific complications.

Overall, complications were significantly higher in patients with OUD. We report higher rates of postoperative pulmonary embolism and blood transfusions. Heroin users are susceptible to ischemia from septic emboli secondary to infectious endocarditis.34 A retrospective study35 of deceased IVDUs using mainly opioids and benzodiazepenes from 1997 to 2013 showed a high incidence of pulmonary emboli (43.4%), vascular scarring (8.0%), pulmonary hypertension (10.2%), and right-sided pathology (5.4%). In addition, some users injected crushed prescription opioids in combination with other foreign substances, such as aspirin, caffeine, and talcum powder, which can directly embolize to form nonseptic emboli.34,36

Injection of opioid tablets intended for oral use may also contribute to the increase in blood transfusions. Just as in our study population, increased rates of anemia have been reported among IVDUs, although there is no consensus regarding the etiology.37,38,39 Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia generally occurs where red blood cells directly contact diseased blood vessels, especially in cases of inflammation, emboli, and pulmonary hypertension.40 Since these risk factors are all reported among IVDUs, it is possible that IVDUs are predisposed to microangiopathic hemolytic anemia and, hence, increased postoperative blood transfusions. A thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura–like anemia has in fact been reported in cases of persistent intravenous opioid use.41

We found that patients with OUD had significantly higher rates of mechanical ventilation. Respiratory compromise may be related to predisposition of IVDUs to pulmonary hypertension. However, respiratory depression is also a pronounced characteristic of opioid overdose.42,43 In the general patient population, incidence of respiratory depression from postoperative narcosis varies from 0.3% to 37%.44 Given the findings of our study, we suspect that OUD status increases the risk of opioid overdose–related respiratory depression. Although we report no significant difference in respiratory failure, this is most likely because of the way these complications are coded. It is likely that patients were either coded for postoperative mechanical ventilation or respiratory failure but not both.

Opioid tolerance and hyperalgesia are common among persistent opioid users, supported by our finding that these patients also had higher rates of prolonged postoperative pain.44,45 This poses significant implications for perioperative pain management. Perioperative analgesia in opioid-dependent patients should effectively treat pain while minimizing the risks of postoperative addiction or withdrawal. International Association for the Study of Pain 2017 guidelines recommend that analgesia should be titrated to effect, ideally by a multimodal approach that makes use of regional, adjuvant, and nonopioid methods in either the preoperative (anesthesia) or postoperative setting.46 N-methyl-d-aspartate antagonists can be successful in targeting hyperalgesia, with reports indicating as much as 50% reduction in postoperative pain and a decrease in patient-controlled opioid consumption from a single methadone bolus of 0.2 mg/kg before surgical incision.47 Many protocols for opioid-dependent patients have also been developed with success using low-dose subanesthetic ketamine infusions postoperatively, usually at 60 to 120 μg/kg/h over 4 hours.47 The multimodal approach should also address the psychological component of pain, since our results show high rates of depression among patients with OUD.47,48

Limitations

Although our study provides insight into the trends and outcomes of cardiac surgery in patients with OUD, there are inherent limitations. The NIS database is an administrative database based on billing data and, as such, only provides discharge-level information. Specific clinical data, such as quantification of persistent opioid use, postoperative pain management, or operation-specific factors, are not available. This also limits our ability to surmise the true etiology of complications associated with OUD. Because the database relies on a set of clinical diagnosis codes, it is possible that OUD is underreported and that the definitions of opioid dependence or persistent opioid use are not consistent from hospital to hospital.

Despite these limitations, the NIS database is ideal for the objective of our study: to investigate trends and hospital-level outcomes on a national scale in a rare subset of patients through access to data on millions of operations. Our study provides an overall clinical picture of outcomes that can be anticipated for the OUD population. The presence of OUD preoperatively is not currently a component of standard preoperative risk assessment. Our findings suggest that there may be value in incorporating OUD status into assessment algorithms (eg, the Society of Thoracic Surgeons risk calculator) to give surgeons and clinicians a clearer picture of operative outcomes. Future work examining specific operative factors and clinical end points will allow for more thorough guidelines that not only shape medical and surgical management of these patients but also prevent consequences of persistent opioid use in the operative setting.

Conclusions

In conclusion, preoperative OUD in cardiac surgery patients does not increase mortality but confers an increased burden of morbidity and resource utilization. Trends in patient volume and morbidity reported in our study suggest that cardiac surgeons are likely to encounter this population of patients more often now than in the past and should be prepared to adequately manage the perioperative factors specific to them. In urgent situations, patients need not be denied cardiac surgery because of their OUD status, although close postoperative monitoring is suggested.

eTable 1. Unadjusted outcomes after cardiac surgery in patients with and without opioid use disorder.

eTable 2. Post hoc analysis of propensity-matched outcomes after cardiac surgery in patients with and without opioid use disorder excluding endocarditis from propensity matching.

eFigure. Covariance balance plot for cardiac surgery patients with and without opioid use disorder before and after propensity matching.

References

- 1.Schuchat A, Houry D, Guy GP Jr. New data on opioid use and prescribing in the United States. JAMA. 2017;318(5):425-426. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.8913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, Scholl L. Increases in drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths—United States, 2010-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(50-51):1445-1452. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm655051e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Florence CS, Zhou C, Luo F, Xu L. The economic burden of prescription opioid overdose, abuse, and dependence in the United States, 2013. Med Care. 2016;54(10):901-906. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frieden TR, Houry D. Reducing the risks of relief: the CDC opioid prescribing guideline. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(16):1501-1504. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1515917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Vital signs: overdoses of prescription opioid pain relievers—United States, 1999–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(43):1487-1492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khodneva Y, Muntner P, Kertesz S, Kissela B, Safford MM. Prescription opioid use and risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and cardiovascular death among adults from a prospective cohort (REGARDS study). Pain Med. 2016;17(3):444-455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carman WJ, Su S, Cook SF, Wurzelmann JI, McAfee A. Coronary heart disease outcomes among chronic opioid and cyclooxygenase-2 users compared with a general population cohort. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20(7):754-762. doi: 10.1002/pds.2131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li L, Setoguchi S, Cabral H, Jick S. Opioid use for noncancer pain and risk of myocardial infarction amongst adults. J Intern Med. 2013;273(5):511-526. doi: 10.1111/joim.12035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miró JM, del Río A, Mestres CA. Infective endocarditis and cardiac surgery in intravenous drug abusers and HIV-1 infected patients. Cardiol Clin. 2003;21(2):167-184, v-vi. doi: 10.1016/S0733-8651(03)00025-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hartman L, Barnes E, Bachmann L, Schafer K, Lovato J, Files DC. Opiate injection-associated infective endocarditis in the Southeastern United States. Am J Med Sci. 2016;352(6):603-608. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2016.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lemaire A, Dombrovskiy V, Saadat S, et al. Patients with infectious endocarditis and drug dependence have worse clinical outcomes after valvular surgery. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2017;18(3):299-302. doi: 10.1089/sur.2016.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cauley CE, Anderson G, Haynes AB, Menendez M, Bateman BT, Ladha K. Predictors of in-hospital postoperative opioid overdose after major elective operations: a nationally representative cohort study. Ann Surg. 2017;265(4):702-708. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brummett CM, Waljee JF, Goesling J, et al. New persistent opioid use after minor and major surgical procedures in US adults. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(6):e170504. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun EC, Darnall BD, Baker LC, Mackey S. Incidence of and risk factors for chronic opioid use among opioid-naive patients in the postoperative period. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(9):1286-1293. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.3298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morris BJ, Mir HR. The opioid epidemic: impact on orthopaedic surgery. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23(5):267-271. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-14-00163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levy B, Paulozzi L, Mack KA, Jones CM. Trends in opioid analgesic–prescribing rates by specialty, US, 2007-2012. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(3):409-413. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.02.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Safaii N, Kazemi B. Effect of opium use on short-term outcome in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;58(2):62-67. doi: 10.1007/s11748-009-0529-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sadeghian S, Karimi A, Dowlatshahi S, et al. The association of opium dependence and postoperative complications following coronary artery bypass graft surgery: a propensity-matched study. J Opioid Manag. 2009;5(6):365-372. doi: 10.5055/jom.2009.0036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eizadi-Mood N, Aghadavoudi O, Najarzadegan MR, Fard MM. Prevalence of delirium in opium users after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Int J Prev Med. 2014;5(7):900-906. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rabkin DG, Mokadam NA, Miller DW, Goetz RR, Verrier ED, Aldea GS. Long-term outcome for the surgical treatment of infective endocarditis with a focus on intravenous drug users. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;93(1):51-57. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Østerdal OB, Salminen PR, Jordal S, Sjursen H, Wendelbo Ø, Haaverstad R. Cardiac surgery for infective endocarditis in patients with intravenous drug use. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2016;22(5):633-640. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivv397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Palmer L Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD-9-CM. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp. Accessed December 28, 2017.

- 23.Menendez ME, Ring D, Bateman BT. Preoperative opioid misuse is associated with increased morbidity and mortality after elective orthopaedic surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(7):2402-2412. doi: 10.1007/s11999-015-4173-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ballantyne JC, Sullivan MD, Kolodny A. Opioid dependence vs addiction: a distinction without a difference? Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(17):1342-1343. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Austin PC, Grootendorst P, Anderson GM. A comparison of the ability of different propensity score models to balance measured variables between treated and untreated subjects: a Monte Carlo study. Stat Med. 2007;26(4):734-753. doi: 10.1002/sim.2580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8-27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2011: national estimates of drug-related emergency department visits. http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/DAWN2k11ED/DAWN2k11ED/DAWN2k11ED.pdf. Accessed December 31, 2017.

- 29.Dart RC, Surratt HL, Cicero TJ, et al. Trends in opioid analgesic abuse and mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(3):241-248. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1406143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muhuri PK, Gfroerer JC, Davies MC Associations of nonmedical pain reliever use and initiation of heroin use in the United States. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/DR006/DR006/nonmedical-pain-reliever-use-2013.htm. Accessed December 31, 2017.

- 31.Smith MY, Irish W, Wang J, Haddox JD, Dart RC. Detecting signals of opioid analgesic abuse: application of a spatial mixed effect Poisson regression model using data from a network of poison control centers. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2008;17(11):1050-1059. doi: 10.1002/pds.1658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cochran BN, Flentje A, Heck NC, et al. Factors predicting development of opioid use disorders among individuals who receive an initial opioid prescription: mathematical modeling using a database of commercially-insured individuals. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;138:202-208. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.02.701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nemati MH, Astaneh B, Ardekani GS. Effects of opium addiction on bleeding after coronary artery bypass graft surgery: report from Iran. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;58(9):456-460. doi: 10.1007/s11748-010-0613-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fonseca AC, Ferro JM. Drug abuse and stroke. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2013;13(2):325. doi: 10.1007/s11910-012-0325-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Darke S, Duflou J, Torok M. The health consequences of injecting tablet preparations: foreign body pulmonary embolization and pulmonary hypertension among deceased injecting drug users. Addiction. 2015;110(7):1144-1151. doi: 10.1111/add.12930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kramer ED, Dasgupta N, Lim CC, Lee SH, Wong YC, Hui F. Embolic stroke associated with injection of buprenorphine tablets. Neurology. 2010;74(10):863. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181d2b5f6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dancheck B, Tang AM, Thomas AM, Smit E, Vlahov D, Semba RD. Injection drug use is an independent risk factor for iron deficiency and iron deficiency anemia among HIV-seropositive and HIV-seronegative women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;40(2):198-201. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000165909.12333.07 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Younis N, Casson IF. An unusual cause of iron deficiency anaemia in an intravenous drug user. Hosp Med. 2000;61(1):62-63. doi: 10.12968/hosp.2000.61.1.1868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Savov Y, Antonova N, Zvetkova E, Gluhcheva Y, Ivanov I, Sainova I. Whole blood viscosity and erythrocyte hematometric indices in chronic heroin addicts. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2006;35(1-2):129-133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schofferman J, Billesdon J, Hall R. Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia: another complication of drug abuse. JAMA. 1974;230(5):721. doi: 10.1001/jama.1974.03240050049026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ambruzs JM, Serrell PB, Rahim N, Larsen CP. Thrombotic microangiopathy and acute kidney injury associated with intravenous abuse of an oral extended-release formulation of oxymorphone hydrochloride: kidney biopsy findings and report of 3 cases. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;63(6):1022-1026. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee LA, Caplan RA, Stephens LS, et al. Postoperative opioid-induced respiratory depression: a closed claims analysis. Anesthesiology. 2015;122(3):659-665. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taylor S, Kirton OC, Staff I, Kozol RA. Postoperative day one: a high risk period for respiratory events. Am J Surg. 2005;190(5):752-756. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gulur P, Williams L, Chaudhary S, Koury K, Jaff M. Opioid tolerance: a predictor of increased length of stay and higher readmission rates. Pain Physician. 2014;17(4):E503-E507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Compton P, Canamar CP, Hillhouse M, Ling W. Hyperalgesia in heroin dependent patients and the effects of opioid substitution therapy. J Pain. 2012;13(4):401-409. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schug SA. Management of postsurgical pain in patients treated preoperatively with opioids. https://s3.amazonaws.com/rdcms-iasp/files/production/public/2017GlobalYear/FactSheets/9.%20Preop%20opioid%20treatment.Schug-EE.pdf. Accessed August 19, 2018.

- 47.Vadivelu N, Mitra S, Kaye AD, Urman RD. Perioperative analgesia and challenges in the drug-addicted and drug-dependent patient. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2014;28(1):91-101. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2014.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vadivelu N, Mitra S, Kai AM, Kodumudi G, Gritsenko K. Review of perioperative pain management of opioid-dependent patients. J Opioid Manag. 2016;12(4):289-301. doi: 10.5055/jom.2016.0344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Unadjusted outcomes after cardiac surgery in patients with and without opioid use disorder.

eTable 2. Post hoc analysis of propensity-matched outcomes after cardiac surgery in patients with and without opioid use disorder excluding endocarditis from propensity matching.

eFigure. Covariance balance plot for cardiac surgery patients with and without opioid use disorder before and after propensity matching.