Abstract

This long-term follow-up of a randomized trial reporting no apparent effect of high-dose vs standard-dose prenatal vitamin D supplementation on wheezing in children at the age of 3 years extends the findings an additional 3 years and describes asthma risk at the age of 6 years.

Evidence suggests that low in utero vitamin D levels may be associated with risk of asthma in offspring.1 The Copenhagen Prospective Studies on Asthma in Childhood 2010 vitamin D randomized clinical trial (RCT) found that at the age of 3 years, children of women randomized to high-dose vs standard-dose vitamin D did not have a statistically significant reduced risk of persistent wheeze; however, a clinically important protective effect could not be excluded (hazard ratio, 0.76 [95% CI, 0.52-1.12]).2 Because diagnosing asthma early in life is difficult, we followed up the children at the age of 6 years to assess the risk of current asthma.

Methods

During week 24 of pregnancy, women were randomized to receive 2400 IU/d of vitamin D or placebo in addition to the recommended intake of 400 IU/d of vitamin D at 1 center in Copenhagen between March 2009 and November 2010. Their offspring attended 12 scheduled clinic visits until the age of 6 years, with additional acute care visits for any respiratory symptom; follow-up was through March 2017. Because of the delay in receiving ethical approval, 623 women of the 738 eligible were enrolled; 581 children were analyzed at the age of 3 years, at which time the study was unblinded.

Details of the study have been published.2 Extension of the trial was planned in mid-2013 before any data were examined. The National Committee on Health Research Ethics approved the follow-up by October 2013. Oral and written informed consent for the follow-up was obtained from the parents. The protocol for the trial extension appears in Supplement 1.

The primary outcome of the RCT2 was persistent wheeze through the age of 3 years that was diagnosed by study pediatricians following a predefined, validated diagnostic algorithm.3 The diagnosis was termed persistent wheeze during the first 3 years of life and asthma thereafter. Asthma at the age of 6 years was the primary outcome of the follow-up and was defined as fulfilling the diagnostic criteria at any point during childhood and needing inhaled corticosteroids at the age of 6 years. Prespecified secondary outcomes at the age of 6 years were lung function measurements, bronchial reactivity to methacholine, fractional exhaled nitric oxide concentration, allergic sensitization, and rhinitis.

The primary outcome was analyzed using logistic regression and was adjusted for sex, season of birth, the mother’s vitamin D level at randomization, and randomization group of a concomitant RCT on n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids.4 The yearly prevalence of persistent wheeze or asthma at the ages of 1 through 6 years was analyzed post hoc with a repeated-measures generalized estimating equation model. Secondary outcomes were analyzed using logistic and linear regression models. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc) and a 2-sided statistical significance threshold of .05. No imputation was performed for missing data.

Results

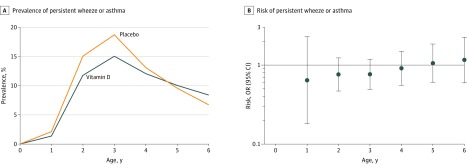

At the age of 6 years, 545 of the 581 children (94%) were available for the analysis. Mothers of children lost to follow-up were of lower socioeconomic status and more likely to smoke. Asthma was diagnosed in 23 of 274 children (8%) in the high-dose vitamin D group compared with 18 of 268 children (7%) in the placebo group (odds ratio [OR], 1.27 [95% CI, 0.67-2.42], P = .46; adjusted OR, 1.21 [95% CI, 0.63-2.32], P = .57). An analysis of the yearly prevalence of persistent wheeze or asthma through the age of 6 years also showed no effect of the supplementation (OR, 0.87 [95% CI, 0.59-1.28], P = .48; Figure).

Figure. Effect of Vitamin D Supplementation on Yearly Prevalence of Persistent Wheeze or Asthma.

A, Yearly prevalence of persistent wheeze or asthma during 6 years of clinical follow-up of children born to mothers receiving high-dose vitamin D or placebo in addition to the recommended intake of 400 IU/d during the third trimester of pregnancy. B, Corresponding yearly odds ratios (ORs) for the risk of persistent wheeze or asthma at the ages of 1 through 6 years. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

No significant differences were observed for lung function outcomes, bronchial reactivity, fractional exhaled nitric oxide concentration, allergic sensitization, or rhinitis by the age of 6 years (Table).

Table. Effect of High-Dose Vitamin D Supplementation During Pregnancy on Offspring Risk of Asthma, Lung Function, Bronchial Responsiveness, and Allergy Outcomes by the Age of 6 Years.

| High-Dose Vitamin D | Placebo | Estimate (95% CI) | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Total No. | Cases | Total No. | |||

| Primary Outcome | ||||||

| Asthma at the age of 6 y, No. (%) | ||||||

| Unadjusted analysis | 23 (8) | 274 | 18 (7) | 268 | OR: 1.27 (0.67 to 2.42) | .46 |

| Adjusted analysisa | 22 (8) | 272 | 18 (7) | 267 | AOR: 1.21 (0.63 to 2.32) | .57 |

| Secondary Outcomes | ||||||

| Lung function, mean (SD) | ||||||

| FEV1, L | 1.33 (0.16) | 224 | 1.34 (0.17) | 213 | MD: −0.01 (−0.04 to 0.02) | .44 |

| MMEF, L/s | 1.66 (0.33) | 224 | 1.69 (0.42) | 213 | MD: −0.03 (−0.10 to 0.04) | .37 |

| FEV1:FVC ratio | 0.93 (0.05) | 224 | 0.92 (0.06) | 213 | MD: 0.004 (−0.01 to 0.01) | .49 |

| Specific airway resistance, kPa/s | 1.09 (0.03) | 233 | 1.09 (0.03) | 230 | MD: 0.001 (−0.04 to 0.06) | .69 |

| Bronchial responsiveness, geometric mean (SD) | ||||||

| PD20, μmoL | 1.17 (3.93) | 211 | 1.11 (3.52) | 207 | GMD: 0.94 (−0.73 to 1.22) | .66 |

| Airway inflammation, geometric mean (SD) | ||||||

| FeNO, ppb | 6.4 (2.2) | 177 | 6.5 (1.8) | 163 | GMD: −1.0 (−1.2 to 0.9) | .72 |

| Allergy outcomes, No. (%) | ||||||

| Sensitization, specific IgE | 68 (29) | 231 | 55 (25) | 223 | OR: 1.27 (0.84 to 1.93) | .25 |

| Sensitization, skin prick test | 21 (9) | 226 | 11 (5) | 214 | OR: 1.89 (0.89 to 4.02) | .10 |

| Allergic rhinitis | 22 (8) | 227 | 16 (6) | 269 | OR: 1.36 (0.70 to 2.66) | .36 |

Abbreviations: AOR, adjusted odds ratio; FeNO, fractional exhaled nitric oxide; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in the first second; FVC, forced vital capacity; GMD, geometric mean difference; MD, mean difference; MMEF, maximal mid-expiratory flow; OR, odds ratio; PD20, provocative dose of methacholine resulting in a 20% decrease in FEV1 from baseline.

Adjusted for sex, season of birth, randomization group of concomitant randomized clinical trial of n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids, and maternal serum vitamin D level at time of randomization.

Discussion

High-dose compared with standard-dose vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy was not associated with the child’s risk of asthma by the age of 6 years, at which time a diagnosis can be established using traditional measures. There also were no associations with lung function or bronchial hyperreactivity, which are key elements in asthma pathogenesis, and no association with allergy outcomes, suggesting that a benefit was not overlooked. The possible clinically important protective effect of vitamin D on persistent wheeze at the age of 3 years was not found at the age of 6 years.

The main limitations of the study are reduced statistical power, evidenced by the wide 95% CIs because the target sample was not reached, and the potential information bias from unblinding at the age of 3 years.

Future studies should investigate whether the effect of prenatal vitamin D supplementation is modified by environmental, dietary, or genetic factors.

Section Editor: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor.

Study Protocol

Data Access Statement

References

- 1.Feng H, Xun P, Pike K, et al. In utero exposure to 25-hydroxyvitamin D and risk of childhood asthma, wheeze, and respiratory tract infections: a meta-analysis of birth cohort studies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(5):1508-1517. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.06.065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chawes BL, Bønnelykke K, Stokholm J, et al. Effect of vitamin D3 supplementation during pregnancy on risk of persistent wheeze in the offspring: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(4):353-361. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bisgaard H, Pipper CB, Bønnelykke K. Endotyping early childhood asthma by quantitative symptom assessment. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(5):1155-1164. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bisgaard H, Stokholm J, Chawes BL, et al. Fish oil–derived fatty acids in pregnancy and wheeze and asthma in offspring. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(26):2530-2539. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1503734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Study Protocol

Data Access Statement