Key Points

Question

What is the effect of epicutaneous immunotherapy on reactivity to peanut protein ingestion in peanut-allergic children?

Finding

In this randomized clinical trial of 356 peanut-allergic children, the difference in treatment response rate (percentage of participants meeting a defined eliciting dose to peanut challenge) after 12 months of treatment with peanut-patch therapy, compared with placebo, was statistically significant (35.3% vs 13.6%), but did not meet a prespecified criterion (≥15% lower bound of the confidence interval) for a positive trial result.

Meaning

Epicutaneous immunotherapy induced a statistically significant response compared with placebo in peanut-allergic children, but the study did not meet a component of the primary outcome.

Abstract

Importance

There are currently no approved treatments for peanut allergy.

Objective

To assess the efficacy and adverse events of epicutaneous immunotherapy with a peanut patch among peanut-allergic children.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial conducted at 31 sites in 5 countries between January 8, 2016, and August 18, 2017. Participants included peanut-allergic children (aged 4-11 years [n = 356] without a history of a severe anaphylactic reaction) developing objective symptoms during a double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenge at an eliciting dose of 300 mg or less of peanut protein.

Interventions

Daily treatment with peanut patch containing either 250 μg of peanut protein (n = 238) or placebo (n = 118) for 12 months.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was the percentage difference in responders between the peanut patch and placebo patch based on eliciting dose (highest dose at which objective signs/symptoms of an immediate hypersensitivity reaction developed) determined by food challenges at baseline and month 12. Participants with baseline eliciting dose of 10 mg or less were responders if the posttreatment eliciting dose was 300 mg or more; participants with baseline eliciting dose greater than 10 to 300 mg were responders if the posttreatment eliciting dose was 1000 mg or more. A threshold of 15% or more on the lower bound of a 95% CI around responder rate difference was prespecified to determine a positive trial result. Adverse event evaluation included collection of treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs).

Results

Among 356 participants randomized (median age, 7 years; 61.2% male), 89.9% completed the trial; the mean treatment adherence was 98.5%. The responder rate was 35.3% with peanut-patch treatment vs 13.6% with placebo (difference, 21.7% [95% CI, 12.4%-29.8%; P < .001]). The prespecified lower bound of the CI threshold was not met. TEAEs, primarily patch application site reactions, occurred in 95.4% and 89% of active and placebo groups, respectively. The all-causes rate of discontinuation was 10.5% in the peanut-patch group vs 9.3% in the placebo group.

Conclusions and Relevance

Among peanut-allergic children aged 4 to 11 years, the percentage difference in responders at 12 months with the 250-μg peanut-patch therapy vs placebo was 21.7% and was statistically significant, but did not meet the prespecified lower bound of the confidence interval criterion for a positive trial result. The clinical relevance of not meeting this lower bound of the confidence interval with respect to the treatment of peanut-allergic children with epicutaneous immunotherapy remains to be determined.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02636699

This randomized clinical trial compares the efficacy and safety of epicutaneous immunotherapy with a peanut patch vs placebo among peanut-allergic children.

Introduction

Studies conducted between 2011 and 2018 note that peanut allergy affects approximately 1% to 2% of US children.1,2,3 The current standard of care is strict peanut avoidance and rapid administration of epinephrine on presentation of allergic symptoms.4 Peanut allergy is a common cause of emergency department visits for food-induced anaphylaxis and has been associated with fatal reactions.5,6,7 Peanut is a ubiquitous ingredient, complicating successful dietary avoidance, which poses risk of an unintentional exposure, even from small amounts. Consequently, peanut allergy is associated with poor quality of life for both food-allergic individuals and their caregivers, who have indicated that treatment resulting in their child having protection against unintentional peanut exposures would positively affect quality of life.8 Therefore, this population could benefit from a treatment that safely and feasibly results in desensitization (a transient state of reduced reactivity demonstrated by an increased eliciting dose during a posttreatment food challenge), which if translated to actual exposures, might offer protection and reduced risk from unintentional consumption.9

Several approaches to treating peanut allergy have been evaluated, including oral, sublingual, and epicutaneous immunotherapies.10 While both oral and sublingual immunotherapies are well described, less is known about epicutaneous immunotherapy. Epicutaneous immunotherapy uses substantially lower dosing (micrograms vs milligrams), avoids oral allergen ingestion, and may have a more advantageous adverse event profile and better adherence than other therapies.11,12,13,14

In a 12-month, phase 2b, dose-ranging study, a 250-μg peanut-patch dose demonstrated a significantly higher response rate vs placebo, with a favorable adverse event profile in children aged 6 to 11 years.13 The objective of the current study was to assess the efficacy and adverse events associated with 12 months of peanut-patch therapy (250-μg dose) among children aged 4 to 11 years with peanut allergy.

Methods

Trial Design and Participants

This was a phase 3, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. The protocol and informed consent forms were approved by institutional review boards at each site. The protocol is available in Supplement 1 and the statistical analysis plan in Supplement 2. Written informed consent was provided by all participants’ parents or guardians and assent from children 7 years of age or older, or per local institutional review board guidelines. The study was conducted between January 8, 2016, and August 18, 2017.

Participants were recruited from 31 sites in Australia (n = 2 hospitals and 1 allergy clinic), Canada (n = 2 hospitals and 4 clinical research centers), Germany (n = 3 hospitals), Ireland (n = 2 hospitals), and the United States (n = 16 hospitals and 1 clinical research site) (eFigure 1 in Supplement 3). Eligible participants were aged 4 to 11 years at screening with physician-diagnosed peanut allergy, currently following a strict peanut-free diet. Other key inclusion criteria were peanut-specific IgE level greater than 0.7 kUA/L, a peanut skin prick test with a largest wheal diameter of 6 mm or greater (children aged 4-5 years) or 8 mm or greater (children aged ≥6 years) at screening, and an eliciting dose (the single highest dose at which a patient exhibited objective signs or symptoms of an immediate hypersensitivity reaction) of 300 mg or less of peanut protein based on a double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenge.

For potential ethical and safety reasons regarding an increased risk of triggering a severe/potentially life-threatening reaction during the entry peanut challenge, participants having a history of severe anaphylaxis (hypotension requiring vasopressor support, hypoxia requiring mechanical ventilation, or neurological compromise) to peanut or with an unstable chronic condition, including poorly controlled asthma (per Global Initiative for Asthma guidelines), were excluded from the study. Children with a history of anaphylaxis were not excluded as long as the anaphylaxis did not escalate to the aforementioned degree of care, nor were children with persistent asthma, if controlled.15 Conducting an oral food challenge in someone with poorly controlled asthma is routinely contraindicated in both the clinical and research settings for safety reasons.4,16

Standardized, double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenges (per PRACTALL guidelines), using a standardized, blinded food matrix centrally provided to all centers, were conducted during screening and after 12 months of treatment.17 During the entry challenge, increasing peanut-protein doses were administered every 30 minutes to a maximum dose of 300 mg according to the following schedule: 1, 3, 10, 30, 100, and 300 mg. The 12-month food challenge followed the same procedure with additional doses of 1000 and 2000 mg.

Food challenges were discontinued when objective signs or symptoms emerged meeting prespecified stopping criteria requiring treatment (eTable 1 in Supplement 3). Subjective symptoms (eg, abdominal pain or oropharyngeal itching) were assessed and recorded, but alone were insufficient to stop the challenge. Participants were only included if they developed objective symptoms per criteria during the active and not the placebo challenge; the dose at which objective symptoms resulted in ending the food challenge was considered the participant’s eliciting dose. Randomization was then stratified by baseline eliciting dose of 10 mg or less (low–eliciting dose subgroup) or greater than 10 mg to 300 mg (high–eliciting dose subgroup). Adherence was defined as the total number of patches applied in the treatment period divided by the number of days in that period. Caregiver-reported race/ethnicity (in compliance with Food and Drug Administration [FDA] submission standards, categories included white/Caucasian, black/African American, Asian, Hispanic, and other) was collected by investigator/staff, per recommendation of regulatory authorities and as is common to report in clinical trials.

Interventions

Participants were randomized 2:1, stratified by screening eliciting dose, to receive a 250-μg peanut protein or placebo patch applied daily on the interscapular area (eFigure 2 in Supplement 3). Randomization was determined using a computer-generated random number; there was a blocking schema for each stratification criterion (screening eliciting-dose stratum), and the block size was 6. Randomization was stratified according to baseline eliciting dose assuming that at least 30% of participants, based on phase 2 data,13 would comprise the low–eliciting dose subgroup (≤10mg). The first patch was applied for 3 hours under medical supervision at the study site; the daily application duration time was then increased gradually at home to 6 hours per day during week 1, 12 hours per day during week 2, and 24 hours (±4 hours allowance) thereafter. Patches were identical in size and shape and differed in that placebo patches were devoid of peanut protein.

Outcomes

The primary measure of treatment effect was the response rate difference between active and placebo treatment groups after 12 months. Treatment response was defined as a posttreatment eliciting dose of 300 mg or more or 1000 mg or more of peanut protein for the low– or high–eliciting dose subgroups, respectively.

There were 6 prespecified secondary outcomes (some analyzed both overall and by subgroups) that were to be analyzed in hierarchical order (eTable 2 in Supplement 3). Responder rate comparisons by eliciting dose subgroup, eliciting dose by treatment group, and cumulative reactive dose by treatment group are detailed in this article, but the results for the other secondary outcomes are not presented. Among the exploratory outcomes prespecified in the protocol, only changes in peanut-specific IgE and IgG4 in the peanut-patch and placebo-patch groups at months 3, 6, and 12 from baseline are reported.

Adverse event outcomes included treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs), serious TEAEs, and TEAEs of special interest, including grade 4 local cutaneous reactions and systemic allergic TEAEs considered peanut-patch related. Severe anaphylaxis was defined by the presence of cyanosis, hypoxia, hypotension, confusion, loss of consciousness, or incontinence. Adverse events were assessed by investigators, and a serious adverse event was defined according to the International Conference on Harmonisation–Good Clinical Practice definition. Skin reactions were graded by the site investigator from 0 to 4. Site investigators assessed the causality/relationship between the study drug and adverse event, including anaphylaxis, according to the causality criteria (related, probable, possible, unlikely, or not related). All individuals assessing adverse events were blinded to study drug assignment.

Statistical Power and Sample Size

To evaluate a treatment effect, the lower bound of the 95% CI of the difference between active and placebo response rates was required to exceed a value substantially greater than zero. In the absence of any historical data to guide assessment of food allergy immunotherapy, following input from the FDA, a margin of 15% was selected to be the lower bound criterion for determining clinical relevance and a positive trial result, which if met, would permit a hierarchical analysis of secondary outcomes as specified per the statistical analysis plan.18 A sample size of 330 evaluable participants was determined to yield at least 90% power for the primary outcome analysis, assuming a 40% responder rate with peanut patch and a 10% response rate with placebo patch in the overall population.

Statistical Methods

Categorical variables were summarized using patient counts and percentages. The denominator for percentages was the number of participants in the population with available data, unless otherwise stated. Continuous variables were summarized using descriptive statistics.

The primary analysis involved all randomized participants, who were then analyzed as randomized (ie, intention-to-treat). Participants with missing food challenge values at 12 months were counted as nonresponders in this analysis. Prespecified sensitivity analyses were also conducted on the groups as randomized population to evaluate the stability of the primary analysis using worst-case imputation (ie, peanut-patch participants who discontinued prior to the posttreatment food challenge were counted as nonresponders and placebo-patch participants who discontinued prior to the posttreatment food challenge were counted as responders). A multiple imputation analysis and analyses adjusted for eliciting dose strata, region, and age were also performed.

The primary analysis was repeated on the completers set (full analysis set) and on the per-protocol population, which excluded participants who discontinued from the study prior to the posttreatment food challenge or those with a major protocol deviation. A hierarchical inferential approach was used to help control for type I error in that the prespecified criterion of the lower bound had to be met to permit additional analysis of secondary outcomes.

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute). The primary outcome was assessed using a 2-sided Wald test at a 5% level to evaluate a null hypothesis of no difference in response rates, supplemented with a 2-sided Newcombe 95% CI (SAS FREQ procedure with RISKDIFF option), with additional secondary outcomes measured by analysis of covariance. For sensitivity analyses, the adjusted difference in response rate analysis was performed using Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel weighting strategy with a 2-sided Newcombe 95% CI. Additional post hoc testing to adjust for potential effects from multiple sites was conducted using generalized linear mixed models with site as a random factor (Distribution = Binomial, Link = LOGIT; SAS version 9.3).

TEAEs were evaluated for all participants who received at least 1 dose of study drug, which was identical to the groups as randomized population.

Results

Study Participants

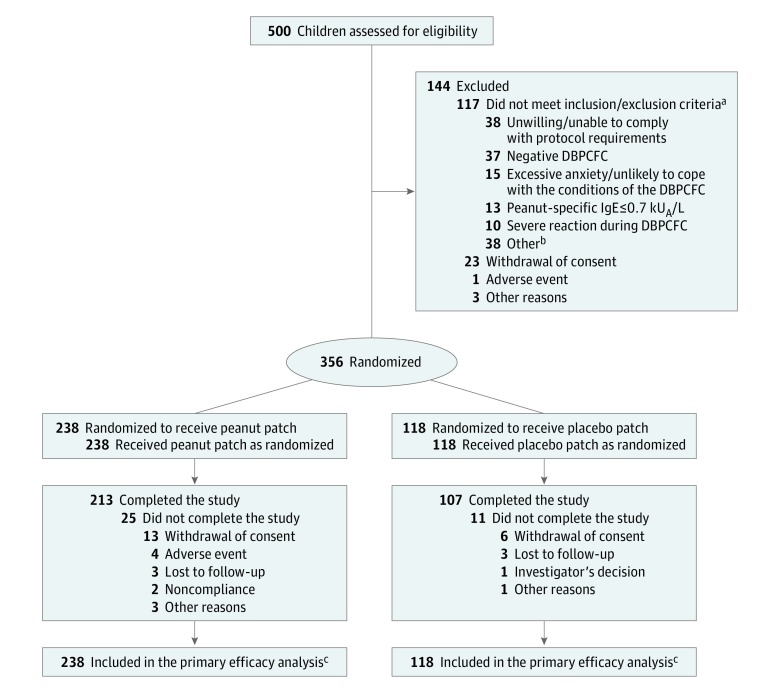

The population for analysis consisted of all 356 randomized participants (61.2% male; median age [Q1, Q3]: 7 [6, 9] years), with 238 and 118 participants randomized to the peanut-patch and placebo-patch groups, respectively (Figure 1). There were 61 participants in the low–eliciting dose subgroup and 295 participants in the high–eliciting dose subgroup. Baseline characteristics in both the treatment and placebo groups regarding eliciting dose subgroup, sex, age, race/ethnicity, and immunologic markers are detailed in Table 1. Treatment adherence was high and comparable between groups, with an overall mean (SD) adherence rate of 98.5% (4.3), and a total of 89.9% of participants completing the trial.

Figure 1. Participant Disposition.

DBPCFC, double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenge; IgE, immunoglobulin E; kUA/L, kilounits of antibody per liter.

aMore than 1 criterion could apply to each participant.

bMajor “other” reasons for exclusion in 3 or more participants included lack of informed consent/assent; skin test not meeting criteria; poorly controlled asthma; inability to perform spirometry required by protocol; or use of short- or long-acting systemic corticosteroids too close (per protocol) to screening.

cParticipants without an assessable DBPCFC were considered nonresponders.

Table 1. Demographics and Baseline Characteristics.

| Category | Peanut Patch (n = 238) | Placebo Patch (n = 118) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, median (Q1, Q3), y | 7 (6, 9) | 7 (5, 9) |

| Sex, No. (%) | ||

| Male | 149 (62.6) | 69 (58.5) |

| Female | 89 (37.4) | 49 (41.5) |

| Race/ethnic origin, No. (%) | ||

| White | 194 (81.5) | 96 (81.4) |

| Black or African American | 1 (0.4) | 2 (1.7) |

| Asian | 19 (8) | 8 (6.8) |

| Hispanic | 2 (0.8) | 0 |

| Othera | 22 (9.2) | 12 (10.2) |

| Peanut-specific IgE, median, kUA/L | 77.9 | 101 |

| Q1, Q3 (range) | 20, 192 (0.78-1008.4) | 29.1, 232 (1.03-1104) |

| Peanut-specific IgG4, median, mg/L | 0.69 | 0.74 |

| Q1, Q3 (range) | 0.28, 1.39 (0.07-10.2) | 0.29, 1.5 (0.07-12.7) |

| Peanut protein eliciting dose, median, mg | 100 | 100 |

| Q1, Q3 (range) | 30, 300 (1-300) | 30, 300 (1-300) |

| Baseline eliciting dose, No. (%) | ||

| 1 mg | 3 (1.3) | 3 (2.5) |

| 3 mg | 10 (4.2) | 7 (5.9) |

| 10 mg | 28 (11.8) | 10 (8.5) |

| 30 mg | 24 (10.1) | 19 (16.1) |

| 100 mg | 97 (40.8) | 40 (33.9) |

| 300 mg | 76 (31.9) | 39 (33.1) |

| Medical history, No. (%) | ||

| Asthma | 117 (49.2) | 52 (44.1) |

| Eczema/atopic dermatitis | 139 (58.4) | 79 (66.9) |

| Allergic rhinitis | 132 (55.5) | 67 (56.8) |

| Allergy(ies) other than peanut | 205 (86.1) | 100 (84.7) |

Abbreviations: kUA/L, kilounits of antibody per liter; Q1, quartile 1; Q3, quartile 3.

Other categories: half white, half Persian; half Indian, quarter Hispanic, quarter white; quarter Filipino; 7/8 white, 1/8 Hispanic; African; American Indian; Asian and white; black and Hispanic; white and Asian (Indian); white and South Asian; white/Asian; father: Australian and mother: Iranian; German, Irish, Eastern European; half white and half black; Hispanic; Hispanic white; Indian; Mexican American; mixed; mother: Armenian and father: Korean; mother: white and father: Asian; multiracial; non-Hispanic; North African (Morocco); South Asian; South Asian/white; and participant reports both white and Asian.

Assessment of Clinical Response

Primary Outcome

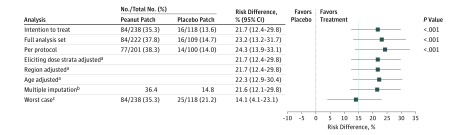

Two hundred thirteen of the 238 participants randomized to the peanut patch and 107 of the 118 participants randomized to the placebo patch completed the study. After 12 months, among all randomized participants, a significantly larger percentage of participants were responders to peanut-patch treatment (responders = 84; 35.3%) vs placebo-patch treatment (responders = 16; 13.6%), with a difference of 21.7% (95% CI, 12.4%-29.8%; P < .001). The lower bound of the 95% CI of the difference (12.4%) crossed the prespecified lower limit of 15%, and thus the trial could not be considered positive. All of the sensitivity analyses regarding the primary outcome were statistically significant, but the lower CI did not meet the 15% criterion (Figure 2). The post hoc analysis adjusting for site was also not statistically significant (eTable 3 in Supplement 3).

Figure 2. Differences in Response Rates Between the Peanut-Patch and Placebo-Patch Groups.

To assess the degree of benefit in favor of peanut patch, a threshold of ≥15% on the lower bound of a 95% CI around responder rate difference was prespecified (blue dotted line). The intention-to-treat analysis was composed of all participants who were randomized.

aAdjusted difference in response rates analysis (Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel method: peanut patch = 238, placebo patch = 118). Adjusted percentages of responders within each treatment group and P values were not computed.

bPrimary efficacy end point using multiple imputation of missing data analysis; only proportion difference and CI were computed.

cWorst-case imputation counted peanut-patch participants who discontinued prior to posttreatment food challenge as nonresponders and placebo-patch participants who discontinued as responders.

Secondary and Exploratory Outcomes

Because the lower bound CI of 15% for the primary outcome was not equaled or exceeded, per the prespecified statistical analysis plan, further hierarchical analyses of secondary and exploratory outcomes are not reported. These data are available in supplemental materials (eFigures 3 and 4 and eTable 4 in Supplement 3).

Adverse Events

The incidence of TEAEs was 95.4% in the peanut-patch group and 89% in the placebo-patch group (Table 2; eTables 5 and 6 in Supplement 3). The most commonly reported treatment-related TEAEs were application site reactions, including pruritus (peanut patch: 34.5%; placebo patch: 11.9%); erythema (peanut patch: 28.2%; placebo patch: 16.9%), and site swelling (peanut patch: 16%; placebo patch: 1.7%) (Table 2). As per investigator assessment, skin reactions were more frequent through month 1 of patch application, decreased thereafter, and were mostly grade 1 or 2 (eFigure 5 in Supplement 3). Five participants in the peanut-patch group had grade 4 skin reactions; none led to permanent treatment discontinuation.

Table 2. Summary of Treatment-Emergent Adverse Events (TEAEs) Considered Related to the Patch by Treatment Groupa.

| System Organ Class Preferred Term | Peanut Patch, 250 μg (n = 238) | Placebo Patch (n = 118) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | No. of Events | Exposure-Adjusted Event Rateb | No. (%) | No. of Events | Exposure-Adjusted Event Rateb | |

| Any TEAE considered related to patchc | 142 (59.7) | 569 | 2.413 | 41 (34.7) | 157 | 1.363 |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 137 (57.6) | 510 | 2.163 | 32 (27.1) | 138 | 1.198 |

| Administration site conditions | 137 (57.6) | 508 | 2.154 | 32 (27.1) | 138 | 1.198 |

| Pruritusd | 82 (34.5) | 152 | 0.645 | 14 (11.9) | 30 | 0.26 |

| Erythemad | 67 (28.2) | 118 | 0.5 | 20 (16.9) | 54 | 0.469 |

| Swellingd | 38 (16) | 86 | 0.365 | 2 (1.7) | 18 | 0.156 |

| Eczema | 25 (10.5) | 29 | 0.123 | 6 (5.1) | 18 | 0.156 |

| Application site reaction | 21 (8.8) | 29 | 0.123 | 2 (1.7) | 5 | 0.043 |

| Urticaria | 15 (6.3) | 23 | 0.098 | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 |

| Dermatitis | 10 (4.2) | 27 | 0.115 | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 |

| Irritation | 8 (3.4) | 10 | 0.042 | 2 (1.7) | 3 | 0.026 |

| Rash | 6 (2.5) | 6 | 0.025 | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 |

| Edema | 5 (2.1) | 7 | 0.03 | 1 (0.8) | 5 | 0.043 |

| General disorders | 2 (0.8) | 2 | 0.008 | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 13 (5.5) | 17 | 0.072 | 10 (8.5) | 14 | 0.122 |

| Urticaria | 5 (2.1) | 8 | 0.034 | 2 (1.7) | 3 | 0.026 |

| Immune system disorders | 12 (5) | 15 | 0.064 | 1 (0.8) | 1 | 0.009 |

| Anaphylactic reaction | 8 (3.4) | 10 | 0.042 | 1 (0.8) | 1 | 0.009 |

| Nonanaphylactic hypersensitivity reaction | 4 (1.7) | 5 | 0.021 | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 |

| Eye disorders | 8 (3.4) | 9 | 0.038 | 1 (0.8) | 1 | 0.009 |

| Allergic conjunctivitis | 4 (1.7) | 4 | 0.017 | 1 (0.8) | 1 | 0.009 |

| Infections and infestations | 6 (2.5) | 9 | 0.038 | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 |

| Respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal disorders | 3 (1.3) | 7 | 0.03 | 2 (1.7) | 2 | 0.017 |

| Psychiatric disorders | 1 (0.4) | 1 | 0.004 | 1 (0.8) | 1 | 0.009 |

| Vascular disorders | 1 (0.4) | 1 | 0.004 | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 |

| TEAE considered related to patche | ||||||

| Serious | 3 (1.3) | 4 | 0.017 | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 |

| Severe | 8 (3.4) | 30 | 0.127 | 1 (0.8) | 1 | 0.009 |

| Moderate | 51 (21.4) | 161 | 0.683 | 5 (4.2) | 14 | 0.122 |

| Mild | 121 (50.8) | 378 | 1.603 | 40 (33.9) | 142 | 1.233 |

| TEAEs considered related to patch leading to temporary discontinuation | 16 (6.7) | 26 | 0.110 | 2 (1.7) | 3 | 0.026 |

| TEAEs considered related to patch leading to permanent discontinuation | 4 (1.7) | 4 | 0.017 | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 |

Subcategory events occurring at a frequency of less than 1% are not listed. A full table of TEAEs considered related to the patch is presented in eTable 6 in Supplement 3. The following categories had no related reported TEAEs: nervous system disorders; injury, poison, and procedural complications; musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders; ear and labyrinth disorders; neoplasms; metabolism and nutrition disorders; blood and lymphatic disorders; congenital, familial, and genetic disorders; hepatobiliary disorders; renal and urinary disorders; reproductive system and breast disorders; surgical and medical procedures; and social circumstances.

Exposure-adjusted event rate based on the number of events divided by the total exposure of participants (235.8 patient-years for the peanut-patch group and 115.2 for the placebo group).

Adverse events reported as possibly related, probably related, or related are considered as related. Adverse events reported as unlikely related or unrelated are considered as unrelated.

Swelling, pruritus, and erythema (swelling, itching, and redness) were to be reported as an adverse event after the first 6 months and in participant diaries on a daily basis during the first 6 months.

Serious, severe, moderate, and mild TEAEs are defined in eTable 5 in Supplement 3.

There were 4 TEAEs experienced by 4 participants (4/356, 1.1% of the overall groups as randomized population), all in the peanut-patch group (4/238, 1.7%), that led to permanent discontinuation. The all-causes rate of discontinuation was 10.5% in the peanut-patch group vs 9.3% in the placebo group. The most common reason for discontinuation was withdrawal of consent (5.5% in the peanut-patch group and 5.1% in the placebo-patch group). There were no TEAEs or discontinuations attributable to gastrointestinal adverse effects.

The numbers of participants reporting serious TEAEs at any time during the study (excluding those during food challenges) were 10 (4.2%) in the peanut-patch group and 6 (5.1%) in the placebo-patch group. Three peanut-patch group participants experienced a total of 4 TEAEs that were assessed and reported by the site investigator as treatment related and met the definition of serious. These were classified as moderate anaphylactic reactions without evidence of cardiovascular, neurologic, or respiratory compromise. All 3 participants responded to standard treatment(s) (eg, epinephrine [1 autoinjection each], antihistamine, corticosteroid); however, 2 of these participants permanently discontinued from the study.

Site investigators reported a total of 26 cases of anaphylactic reactions in 23 participants, irrespective of the assessed causal relationship, including the 4 aforementioned cases. Among these 26 reported cases, 10 in the peanut-patch group were determined by site investigators to be related by some degree (related/probably/possibly); these 10 events occurred in 8 of 238 peanut-patch participants (3.4%), and all were of mild to moderate severity (eTable 7 in Supplement 3). Four of the 10 anaphylactic episodes were not treated with epinephrine; those who did receive epinephrine were treated with 1 dose and assessed as possibly related (2 participants), probably related (1 participant), or related (3 participants) to the peanut patch. No participant was treated with supplemental oxygen. Three anaphylactic episodes occurred in 1 participant (days 16, 83, and 349) who later discontinued the study; 2 participants discontinued the study following 1 episode of anaphylaxis each, 1 participant at day 5 and 1 at day 9. The remaining 5 of 8 participants (62.5%) resumed dosing and remained in the study, with no further episodes of suspected patch-related anaphylaxis (eTable 7 in Supplement 3).

Table 2 (and eTable 6 in Supplement 3) shows all TEAEs that were considered probably, possibly, or related to the patch by treatment groups, listed by organ system and by specific symptoms. The most frequently reported occurrences that were probably, possibly, or related to the peanut patch were attributable to localized patch administration site events. The exposure-adjusted event rate for probably, possibly, or related anaphylaxis was 0.042 per patient-year.

Discussion

In this phase 3 study, there was a statistically significant difference in the proportion of responders randomized to epicutaneous immunotherapy with 250 μg of peanut protein vs placebo in desensitizing peanut-allergic children to peanut protein, as demonstrated by an increase in the eliciting dose on food challenge. This was accomplished with a high degree of adherence to therapy and a low rate of serious adverse events. However, despite the statistical significance in the proportion of responders, the lower bound of the 95% CI of the difference between peanut-patch and placebo-patch treatment groups (12.4%) missed equaling or exceeding the 15% prespecified margin. Thus, the primary analysis did not meet the prespecified success criterion, and statistical significance of secondary outcomes in the hierarchical sequence could not be claimed.

There is no precise determination or consensus regarding what threshold of sensitivity may confer clinically meaningful protection. The convention recommended by the FDA and agreed to by the sponsor is a statistical measure of supersuperiority vs placebo for the lower bound of the CI of the difference between active and placebo treatment groups.18 Although such convention has been used in evaluating new pharmacologic products, such as sublingual immunotherapy for environmental allergies, there is no known clinical significance or biologic plausibility to this 15% margin with respect to epicutaneous, oral, or sublingual food immunotherapy given there are no established treatments in this area for effect size comparison.

While the double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenge has been used in this and other trials as the primary tool to determine clinical effect, this remains a surrogate measure. Another way to assess potential benefit of any investigational food allergy immunotherapy is to attempt to determine any effect on reduction of risk to unintentional ingestion. Based on quantitative risk assessment modeling using databases of consumption amounts and peanut-protein contamination of common foods, Baumert et al9 found that raising the eliciting dose from 100 mg or less to 300 mg or more would be sufficient to protect against more than 95% of potential reactions to various food product categories due to cross-contamination. Remington et al19 determined a relative risk reduction of 74.7% to 96.6% among patients receiving a peanut patch, vs less than 2.9% receiving placebo, in the chance of reaction due to contaminated packaged food products. These may be better measures for future studies but were not an available option at the time of the finalization and approval of the protocol for this study.

Peanut-patch treatment was well tolerated, with favorable adverse event data consistent with those reported in previous epicutaneous immunotherapy studies.12,13 Systemic allergic reactions were rare and none were severe. Investigators concluded that 10 anaphylactic reactions in 8 participants, 5 of whom continued in the study, were related to the peanut patch to some degree. Relatedness can be a difficult determination with a patch that is worn for 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Investigators relied on the commonly used National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases definition of anaphylaxis, which has been shown to be highly sensitive but moderately specific,20,21 in an attempt to capture as many reactions as possible. Although TEAEs were experienced by most participants, they were mostly local skin reactions that were mild to moderate in severity and decreased after having worn the patch for additional weeks. Only 4 of 238 participants (1.7%) in the active group discontinued treatment due to TEAEs.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the trial was not considered positive secondary to not meeting the prespecified 95% CI lower bound margin to evaluate robustness of effect. However, use of this threshold has unclear clinical significance in treating peanut allergy. Second, the number of participants in the low–eliciting dose subgroup was less than the anticipated 30% based on the distribution observed in the phase 2b study (17.1% vs 33%),13 possibly affecting study results.

Third, this study excluded participants with a history of severe life-threatening anaphylaxis to peanut. However, these exclusions are considered standard in immunotherapy trials that include double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenges for ethical and safety concerns, and few individuals are potentially affected by this limitation. These exclusions could have affected the study results, including secondary outcomes assessing adverse events and acceptability of the peanut patch, and may limit generalizability. A safety study that does not involve a food challenge and so does not restrict such patients is ongoing and will be helpful to ascertain whether there is any concern posed by the patch itself to these patients.

Fourth, visible skin reactions potentially could have created the perception to the caregiver that treatment assignment was unblinded. However, skin reactions were common in both groups and could have been related to patch adhesives and/or using an occlusive system in place for 24 hours. Fifth, the duration of the trial was 12 months, which may not have been long enough to show the full potential benefit of epicutaneous immunotherapy based on a continued and steady response to a longer duration of peanut-patch exposure demonstrated in the phase 2 open-label follow-up study.13 Such potential longer-term outcomes are being evaluated in both an extension phase of this current trial, as well as in a real-world safety trial being conducted in parallel.22

Conclusions

Among peanut-allergic children aged 4 to 11 years, the percentage difference in responders at 12 months with the 250-μg peanut-patch therapy vs placebo was 21.7% and was statistically significant, but did not meet the prespecified lower bound of the confidence interval criterion for a positive trial result. The clinical relevance of not meeting this lower bound of the confidence interval with respect to the treatment of peanut-allergic children with epicutaneous immunotherapy remains to be determined.

Trial Protocol

Statistical Analysis Plan

eFigure 1. Study Design

eFigure 2. Interscapular Patch Placement

eFigure 3. (A) Differences in Response Rates Between the Peanut-Patch and Placebo-Patch Groups; (B) Distribution in Eliciting Dose Changes From Baseline at Month 12 (ITT Population)

eFigure 4. Immunologic Correlates Over Time by Treatment Group

eFigure 5. Local Skin Reactions in the Peanut-Patch Group Over Time per Investigator’s Assessment

eTable 1. Symptom Scoring During Oral Food Challenge

eTable 2. Pre-defined Hierarchical Order for Analysis of Efficacy Endpoints

eTable 3. Post Hoc Analysis Using Site Treated as a Random Effect

eTable 4. Cumulative Reactive Dose (CRD) of Peanut Protein by Treatment Group (ITT Population)

eTable 5. Treatment Emergent Adverse Event Rates by System Organ Class and Preferred Term, by Treatment Group (Safety Population) with Exposure Adjusted Event Rate

eTable 6. Summary of Treatment Emergent Adverse Events Considered Related to the Patch by Treatment Group

eTable 7. Summary of Possibly Related, Probably Related, or Related Anaphylaxis Events Occurring in Peanut-Patch Participants

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Gupta RS, Warren CM, Smith BM, et al. The public health impact of parent-reported childhood food allergies in the United States. Pediatrics. 2018;142(6):e20181235. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-1235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oria MP, Stallings VA, eds; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee on Food Allergies: Global Burden, Causes, Treatment, Prevention, and Public Policy . Finding a Path to Safety in Food Allergy: Assessment of the Global Burden, Causes, Prevention, Management, and Public Policy. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gupta RS, Springston EE, Warrier MR, et al. The prevalence, severity, and distribution of childhood food allergy in the United States. Pediatrics. 2011;128(1):e9-e17. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sampson HA, Aceves S, Bock SA, et al. ; Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters; Practice Parameter Workgroup . Food allergy: a practice parameter update—2014. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134(5):1016-1025.e43. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bock SA, Muñoz-Furlong A, Sampson HA. Further fatalities caused by anaphylactic reactions to food, 2001-2006. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119(4):1016-1018. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.12.622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bock SA, Muñoz-Furlong A, Sampson HA. Fatalities due to anaphylactic reactions to foods. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107(1):191-193. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.112031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ross MP, Ferguson M, Street D, Klontz K, Schroeder T, Luccioli S. Analysis of food-allergic and anaphylactic events in the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121(1):166-171. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greenhawt M, Marsh R, Gilbert H, Sicherer S, DunnGalvin A, Matlock D. Understanding caregiver goals, benefits, and acceptable risks of peanut allergy therapies. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;121(5):575-579. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2018.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baumert JL, Taylor SL, Koppelman SJ. Quantitative assessment of the safety benefits associated with increasing clinical peanut thresholds through immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(2):457-465.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burks AW, Sampson HA, Plaut M, Lack G, Akdis CA. Treatment for food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141(1):1-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keet CA, Seopaul S, Knorr S, Narisety S, Skripak J, Wood RA. Long-term follow-up of oral immunotherapy for cow’s milk allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132(3):737-739.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones SM, Sicherer SH, Burks AW, et al. ; Consortium of Food Allergy Research . Epicutaneous immunotherapy for the treatment of peanut allergy in children and young adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(4):1242-1252.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.08.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sampson HA, Shreffler WG, Yang WH, et al. Effect of varying doses of epicutaneous immunotherapy vs placebo on reaction to peanut protein exposure among patients with peanut sensitivity: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318(18):1798-1809. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.16591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Virkud YV, Burks AW, Steele PH, et al. Novel baseline predictors of adverse events during oral immunotherapy in children with peanut allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(3):882-888.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sampson HA, Muñoz-Furlong A, Campbell RL, et al. Second symposium on the definition and management of anaphylaxis: summary report—second National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease/Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Network symposium. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;47(4):373-380. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Assa’ad AH, Bahna SL, Bock SA, Sicherer SH, Teuber SS; Adverse Reactions to Food Committee of American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology . Work group report: oral food challenge testing. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123(6)(suppl):S365-S383. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.03.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sampson HA, Gerth van Wijk R, Bindslev-Jensen C, et al. Standardizing double-blind, placebo-controlled oral food challenges: American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology–European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology PRACTALL consensus report. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130(6):1260-1274. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Althunian TA, de Boer A, Groenwold RHH, Klungel OH. Defining the noninferiority margin and analysing noninferiority: an overview. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;83(8):1636-1642. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Remington BC, Krone T, Koppelman S. Quantitative risk reduction through epicutaneous immunotherapy (EPIT): results from the PEPITES phase III trial. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;121(5):S11. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2018.09.032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loprinzi Brauer CE, Motosue MS, Li JT, et al. Prospective Validation of the NIAID/FAAN Criteria for Emergency Department Diagnosis of Anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016;4(6):1220-1226. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2016.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campbell RL, Hagan JB, Manivannan V, et al. Evaluation of national institute of allergy and infectious diseases/food allergy and anaphylaxis network criteria for the diagnosis of anaphylaxis in emergency department patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129(3):748-752. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.09.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.ClinicalTrials.gov. Safety Study of Viaskin Peanut to Treat Peanut Allergy (REALISE). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02916446. Accessed January 18, 2019.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

Statistical Analysis Plan

eFigure 1. Study Design

eFigure 2. Interscapular Patch Placement

eFigure 3. (A) Differences in Response Rates Between the Peanut-Patch and Placebo-Patch Groups; (B) Distribution in Eliciting Dose Changes From Baseline at Month 12 (ITT Population)

eFigure 4. Immunologic Correlates Over Time by Treatment Group

eFigure 5. Local Skin Reactions in the Peanut-Patch Group Over Time per Investigator’s Assessment

eTable 1. Symptom Scoring During Oral Food Challenge

eTable 2. Pre-defined Hierarchical Order for Analysis of Efficacy Endpoints

eTable 3. Post Hoc Analysis Using Site Treated as a Random Effect

eTable 4. Cumulative Reactive Dose (CRD) of Peanut Protein by Treatment Group (ITT Population)

eTable 5. Treatment Emergent Adverse Event Rates by System Organ Class and Preferred Term, by Treatment Group (Safety Population) with Exposure Adjusted Event Rate

eTable 6. Summary of Treatment Emergent Adverse Events Considered Related to the Patch by Treatment Group

eTable 7. Summary of Possibly Related, Probably Related, or Related Anaphylaxis Events Occurring in Peanut-Patch Participants

Data Sharing Statement