Key Points

Question

Do hospitals with better patient outcomes for surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) subsequently achieve better transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) outcomes after launching TAVR programs?

Findings

This study demonstrates that hospitals with historically lower risk-adjusted mortality rates after SAVR subsequently achieved better short and long term outcomes for TAVR as measured by 30-day and 1-year mortality.

Meaning

High-quality surgical programs were likely a crucial component of successful TAVR programs, and this metric may shed light on the outcomes that hospitals developing new TAVR programs might achieve.

This national cohort study assesses the quality of hospital outcomes by determining the correlation between mortality after surgical aortic valve replacement procedures and mortality at 30 days and 1 year after transcathether aortic valve replacement procedures.

Abstract

Importance

Hospital outcomes for transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) may be dependent on the quality of evaluation, personnel, and procedural and postprocedural care common to patients undergoing cardiac surgery.

Objectives

We sought to assess whether those hospitals with better patient outcomes for surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) subsequently achieved better TAVR outcomes after launching TAVR programs.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This national cohort included US patients 65 years and older. The analysis used the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ Medicare Provider and Review data collected between January 1, 2010, and September 29, 2015. Only hospitals performing at least 1 SAVR prior to September 1, 2011, and performing at least 1 TAVR after this date were included in the analysis. Data analysis was completed from June 2018 to August 2018.

Interventions

Isolated aortic valve replacements.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Hospital risk-adjusted 30-day mortality for SAVR in the pre-TAVR period was used as a surrogate for SAVR quality. Thirty-day and 1-year TAVR mortality rates were examined after stratification by quartile of baseline hospital risk-adjusted SAVR mortality.

Results

A total of 51 924 TAVR procedures were performed in 519 hospitals, of which 19 798 were performed at hospitals in quartile 1 (the lowest risk-adjusted SAVR mortality rate), 7663 were performed in quartile 2, 10 180 were performed in quartile 3, and 14 283 were performed in quartile 4 (the highest risk-adjusted SAVR mortality rate). Observed mortality rates at 30 days consistently increased with increasing baseline hospital SAVR risk-adjusted mortality (quartile 1, 917 patients [4.6%]; quartile 2, 381 [5.0%]; quartile 3, 521 [5.1%]; quartile 4, 800 [5.6%]; P < .001). The same pattern was observed in 1-year mortality (quartile 1, 3359 [17.0%]; quartile 2, 1337 [17.5%]; quartile 3, 1852 [18.2%]; quartile 4, 2652 [18.6%]; P < .001). After multivariable analysis, compared with the lowest quartile of SAVR mortality, undergoing TAVR at a hospital with higher baseline SAVR mortality continued to be associated with higher 30-day mortality (odds ratios: quartile 2, 1.02 [95% CI, 0.87-1.21]; quartile 3, 1.13 [95% CI, 1.02-1.26]; quartile 4, 1.23 [95% CI, 1.07-1.40]; P = .02) and 1-year mortality (hazard ratios: quartile 2, 1.04 [95% CI, 0.92-1.17]; quartile 3, 1.14 [95% CI, 1.02-1.28]; quartile 4, 1.16 [95% CI, 1.05-1.28]; P = .02).

Conclusions and Relevance

Hospitals with higher SAVR mortality rates also had higher short-term and long-term TAVR mortality after initiating TAVR programs. Quality of cardiac surgical care may be associated with a hospital’s performance with new structural heart disease programs.

Introduction

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) has become a widely used alternative treatment for patients with severe aortic valve stenosis, based on clinical trials demonstrating comparable or even superior results compared with surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) among patients at extreme, high, and intermediate risk for surgery.1,2,3,4,5 Current aortic valve replacement guidelines recommend a comprehensive approach toward treatment selection with periprocedural evaluation by a multidisciplinary heart team that integrates multiple parameters to select the optimal patients for each procedure.6,7

A heart team’s composition may include a variety of groups including cardiologists, cardiac surgeons, case managers, catheterization laboratory team members, operating room staff, and advanced practice professionals. It is likely that the involvement of surgeons and surgical intensive care units may have strong effects on the evaluation, procedural care, and postprocedural management of patients undergoing TAVR procedures. Therefore, it is plausible that the quality of a hospital’s surgical program may be influential in how hospitals fare when they initiate new TAVR programs.

In this study, we evaluated whether hospitals with better outcomes after SAVR also achieved better outcomes after initiating TAVR programs. Specifically, using national data among patients insured by Medicare in fee-for-service programs, we hypothesized that those hospitals with lower risk-adjusted 30-day mortality after SAVR prior to TAVR approval also achieved lower mortality rates after TAVR.

Methods

Study Population

We evaluated patients 65 years and older in the United States using the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Medicare Provider and Review database. We included patients with at least 1 procedural code for SAVR (defined by International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] codes 35.21 or 35.22) or TAVR (ICD-9-CM codes 35.05 or 35.06), between January 1, 2010, and September 29, 2015.8 The Medicare Provider and Review database is a 100% sample of administrative discharge billing claims for inpatient hospitalizations for beneficiaries of Medicare fee-for-service insurance programs, and it has been used extensively for prior research on health outcomes.9,10,11 Only hospitals performing at least 1 isolated SAVR (ie, SAVR without a concomitant coronary artery bypass procedure or other valvular surgery, as defined in eTable 1 in the Supplement) prior to September 1, 2011 (pre-TAVR period), and at least 1 TAVR after this date (post-TAVR period) were included in the analysis. The study was approved by the institutional review board of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, with a waiver of informed consent for retrospective data analysis.

Covariates and Outcomes

Baseline covariates were ascertained using secondary diagnosis codes that were coded as present on admission during the index hospitalization, as well as from principal and secondary diagnosis codes from all hospitalizations in the year prior to the date of admission for the index hospitalization (eTable 2 in the Supplement). Covariates were chosen based on inclusion in the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index, a validated summary measure that has previously been shown to be associated with mortality in the Medicare population.12 To identify hospital characteristics, we used the American Hospital Association’s 2012 Annual Survey Database. The primary outcome was all-cause 30-day mortality determined through linkage of the Medicare Provider and Review files to the Medicare Beneficiary Summary File, which includes vital status information. We additionally determined 1-year mortality as a secondary outcome. Time to death was calculated as the time between the date of the index procedure and the date of death.

Statistical Analysis

Hospital SAVR quality was determined based on a hospital’s risk-adjusted 30-day mortality rate in the period prior to the introduction of TAVR (January 1, 2010, to September 1, 2011). Mortality rates exclusively during the pre-TAVR period were used, because the introduction of TAVR may have influenced SAVR outcomes owing to the shifting of patients from SAVR to TAVR.13 We created a mixed-effects logistic regression model to estimate each hospital’s 30-day risk-adjusted mortality rate for SAVR, adjusting for patient risk factors including age, sex, Elixhauser Comorbidity Index variables, and hospital characteristics, including hospital SAVR volume, teaching status, and number of beds.14 Continuous variables are presented as means and SDs or medians and interquartile ranges [IQRs], and categorical variables are presented as counts and percentages. Risk-adjusted 30-day SAVR mortality in the pre-TAVR period was plotted by hospital in ascending order. Patient characteristics were compared across quartiles of SAVR mortality using 1-way analysis of variance for continuous variables and the Pearson χ2 test or Fisher exact test for categorical variables.

Observed 30-day and 1-year TAVR mortality rates were determined by quartile of risk-adjusted SAVR mortality. To assess whether results were sensitive to the inclusion of low-volume hospitals, we reran the analysis after excluding hospitals with procedure volumes less than 10. Multivariable logistic and Cox regression, accounting for clustering by hospital, were then used to determine the adjusted association between baseline hospital SAVR mortality quartile and 30-day and 1-year TAVR mortality, respectively. Both models were adjusted for patient risk factors, including age, sex, Elixhauser Comorbidity Index, access site, hospital TAVR volume, and other hospital characteristics. We used the same multivariable methods to determine the adjusted association between baseline hospital SAVR mortality rates as a continuous variable and 30-day and 1-year TAVR mortality. Furthermore, we repeated the same method to analyze subgroups based on access site (ie, transfemoral vs transapical), and the results were presented in a forest plot.

Cumulative incidence curves were created to plot time to death, stratified by quartile of SAVR quality. Log-rank tests were used to compare the survival distributions of each group. All statistical analyses were performed in Stata, version 15.0 (StataCorp) from June 2018 to August 2018, using a 2-tailed P value less than .05 for significance.

Results

Overall Results

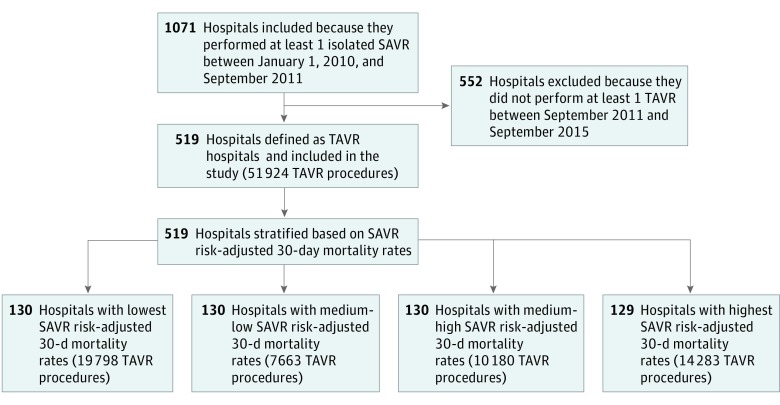

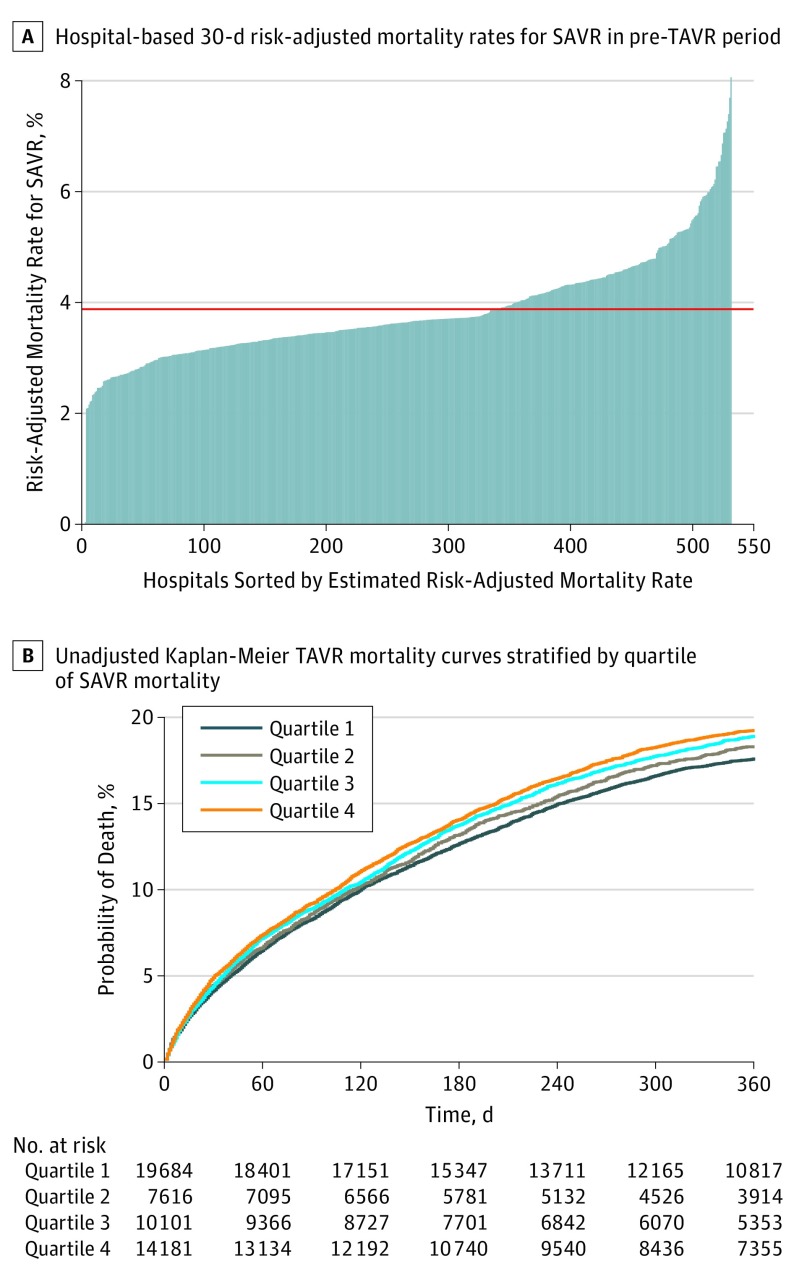

A total of 1071 hospitals performed at least 1 isolated SAVR procedures (n = 33 430) in the pre-TAVR period, of which 519 (48.5%) eventually performed at least 1 TAVR during the study period and were included in the analysis (Figure 1). Of these hospitals, 370 (71.3%) were teaching hospitals and the mean (SD) number of beds was 490 (289). Hospital 30-day risk-adjusted SAVR mortality rates in the pre-TAVR period are shown in Figure 2A. The mean 30-day risk-adjusted SAVR mortality rate in the pre-TAVR period was 3.9% (range, 1.7%-8.1%). A total of 51 924 TAVR procedures were performed after September 1, 2011, in the 519 included hospitals (quartile 1 [the lowest risk-adjusted SAVR mortality], 19 798 procedures; median [IQR], 281 [163-481] procedures; quartile 2, 7663 procedures; median [IQR], 123 [73-197] procedures; quartile 3, 10 180 procedures; median [IQR], 206 [107-402] procedures; quartile 4 [the highest risk-adjusted SAVR mortality], 14 283 procedures; median [IQR], 209 [142-339] procedures; P for median values < .001). Elixhauser Comorbidity Index score (on a scale of 0 to 15 points; mean [SD] score: quartile 1, 6.4 [2.0] points; quartile 2, 6.3 [2.0] points; quartile 3, 6.2 [2.0] points; quartile 4, 6.2 [2.0] points; P < .001) and age (mean [SD] age, quartile 1, 82.6 [8.1] years; quartile 2, 82.3 [7.8] years; quartile 3, 82.5 [7.9] years; quartile 4, 82.2 [8.0] years; P < .001) were significantly higher among patients treated in hospitals in the lowest quartile of SAVR mortality, as well as an additional 20 recorded comorbidities (Table 1).

Figure 1. Study Flow Diagram.

SAVR indicates surgical aortic valve replacement; TAVR, transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

Figure 2. Mortality Rates of Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement (SAVR) and Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement (TAVR).

A, The red dashed line refers to the overall mean.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics and Outcomes of Patients Undergoing Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement (TAVR), Based on Quartiles of Risk-Standardized Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement Mortality Rates in the Pre-TAVR Period per Risk-Adjusted Mortality Ratesa.

| Characteristic | Patients Undergoing TAVR Procedure, No. (%) | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quartile 1 (n = 19 798) | Quartile 2 (n = 7663) | Quartile 3 (n = 10 180) | Quartile 4 (n = 14 283) | ||

| Baseline | |||||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 82.6 (8.1) | 82.3 (7.8) | 82.5 (7.9) | 82.2 (8.0) | <.001 |

| Female | 9476 (47.9) | 3697 (48.4) | 4843 (47.7) | 6926 (48.5) | .50 |

| Congestive heart failure | 15 233 (77.0) | 5668 (74.2) | 7653 (75.3) | 10 838 (76.0) | <.001 |

| Cardiac arrhythmias | 13 355 (67.5) | 5003 (65.5) | 6638 (65.3) | 9406 (65.9) | <.001 |

| Pulmonary circulation disorders | 4860 (24.6) | 1777 (23.3) | 2281 (22.5) | 3353 (23.5) | <.001 |

| Peripheral vascular disorders | 6069 (30.7) | 2249 (29.4) | 2835 (27.9) | 3862 (27.1) | <.001 |

| Hypertension, uncomplicated | 9303 (47.1) | 3763 (49.3) | 5013 (49.3) | 6724 (47.1) | <.001 |

| Hypertension, complicated | 7593 (38.4) | 2857 (37.4) | 3649 (35.9) | 5485 (38.4) | <.001 |

| Paralysis | 198 (1.0) | 75 (1.0) | 107 (1.1) | 151 (1.1) | .92 |

| Other neurological disorders | 1087 (5.5) | 417 (5.5) | 646 (6.4) | 839 (5.9) | .01 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 9604 (48.6) | 3624 (47.4) | 4831 (47.5) | 6755 (47.3) | .09 |

| Diabetes, uncomplicated | 5606 (28.4) | 2327 (30.5) | 3099 (30.5) | 4508 (31.6) | <.001 |

| Diabetes, complicated | 1420 (7.2) | 488 (6.4) | 601 (5.9) | 800 (5.6) | <.001 |

| Hypothyroidism | 4419 (22.4) | 1706 (22.3) | 2236 (22.0) | 3109 (21.8) | .62 |

| Renal failure | 8046 (40.7) | 3026 (39.6) | 3829 (37.7) | 5748 (40.3) | <.001 |

| Liver disease | 649 (3.3) | 251 (3.3) | 293 (2.9) | 423 (3.0) | .14 |

| Peptic ulcer disease, excluding bleeding | 160 (0.8) | 66 (0.9) | 83 (0.8) | 124 (0.9) | .92 |

| AIDS | 11 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (<1) | .002 |

| Lymphoma | 297 (1.5) | 80 (1.0) | 136 (1.3) | 174 (1.2) | .02 |

| Metastatic cancer | 94 (0.5) | 32 (0.4) | 45 (0.4) | 84 (0.6) | .24 |

| Solid tumor without metastasis | 445 (2.3) | 147 (1.9) | 214 (2.1) | 325 (2.3) | .30 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis/collagen vascular | 1090 (5.5) | 425 (5.6) | 518 (5.1) | 691 (4.8) | .02 |

| Coagulopathy | 3973 (20.1) | 1729 (22.6) | 2356 (23.2) | 3132 (21.9) | <.001 |

| Obesity | 3136 (15.9) | 1204 (15.8) | 1410 (13.9) | 2035 (14.3) | <.001 |

| Weight loss | 1238 (6.3) | 299 (3.9) | 508 (5.0) | 668 (4.7) | <.001 |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders | 4961 (25.1) | 2018 (26.4) | 2756 (27.1) | 3598 (25.2) | <.001 |

| Blood loss anemia | 225 (1.1) | 129 (1.7) | 149 (1.5) | 220 (1.5) | <.001 |

| Deficiency anemia | 691 (3.5) | 313 (4.1) | 403 (4.0) | 527 (3.7) | .06 |

| Alcohol abuse | 85 (0.4) | 49 (0.6) | 45 (0.4) | 71 (0.5) | .14 |

| Drug abuse | 27 (0.1) | 24 (0.3) | 15 (0.1) | 27 (0.2) | .02 |

| Psychoses | 164 (0.8) | 80 (1.0) | 103 (1.0) | 150 (1.1) | .13 |

| Depression | 1608 (8.1) | 730 (9.6) | 750 (7.4) | 1125 (7.9) | <.001 |

| Elixhauser Comorbidity Index, mean (SD) | 6.4 (2.0) | 6.3 (2.0) | 6.2 (2.0) | 6.2 (2.0) | <.001 |

| TAVR volume, median (IQR) | 281 (163-481) | 123 (73-197) | 206 (107-402) | 209 (142-339) | <.001 |

| Transapical access | 3045 (15.4) | 1461 (19.1) | 1491 (14.7) | 1952 (13.7) | <.001 |

| Hospital stay length, days, median (IQR) | 5 (3-8) | 5 (4-8) | 5 (3-9) | 5 (3-8) | .66 |

| Observed mortality | |||||

| 30 d | 917 (4.6) | 381 (5.0) | 521 (5.1) | 800 (5.6) | <.001 |

| 1 y | 3359 (17.0) | 1337 (17.5) | 1852 (18.2) | 2652 (18.6) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; TAVR, transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

Each quartile contained 130 hospitals, with the exception of quartile 4, which had 129 hospitals. Quartile 1 had the lowest SAVR mortality rate; quartile 4 had the highest.

Outcomes

Observed 30-day mortality increased with increasing SAVR risk-adjusted mortality (quartile 1, 917 [4.6%]; quartile 2, 381 [5.0%]; quartile 3, 512 [5.1%]; quartile 4, 800 [5.6%]; P < .001). The same result was seen in 1-year mortality (quartile 1, 3359 [17.0%]; quartile 2, 1337 [17.5%]; quartile 3, 1852 [18.2%]; quartile 4, 2652 [18.6%]; P < .001; Table 1). Unadjusted 1-year TAVR mortality curves stratified by quartiles are presented in Figure 2B. The 1-year mortality rate was 17.5% (95% CI, 16.9%-18.1%) for hospitals in quartile 1 (reference), 18.4% (95% CI, 17.5%-19.4%) in quartile 2 (log-rank P = .20), 19.0% (95% CI, 18.3%-19.8%) in quartile 3 (log-rank P = .007), and 19.4% (95% CI, 18.7%-20.1%) in quartile 4 (log-rank P < .001). After exclusion of hospitals performing fewer than 10 TAVRs during the study period, our results were substantively unchanged (eTable 3 in the Supplement).

On multivariable analysis, undergoing TAVR at a hospital with higher baseline SAVR mortality continued to be associated with higher mortality at 30 days after TAVR (Table 2). Compared with quartile 1, the odds ratio (OR) for quartile 2 was 1.02 (95% CI, 0.87-1.21); it was 1.13 for quartile 3 (95% CI, 1.02-1.26) and 1.23 for quartile 4 (95% CI, 1.07-1.40; P = .02 across quartiles). At 1 year, the hazard ratio for quartile 2 was 1.04 (95% CI, 0.92-1.17), while that of quartile 3 was 1.14 (95% CI, 1.02-1.28), and that of quartile 4 was 1.16 (95% CI, 1.05-1.28; P = .02 across quartiles). When modeled as a continuous variable, higher hospital SAVR mortality rates continued to be associated with higher TAVR mortality at 30 days (OR, 1.07 [95% CI, 1.03-1.11]; P < .001) and 1 year (hazard ratio, 1.034 [95% CI, 1.02-1.06]; P < .001).

Table 2. Multivariable Adjusted Association Between Hospital Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement Mortality Quartile and Trancatheter Aortic Valve Replacement Mortality.

| Characteristic | 30-d TAVR Mortality Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

P Value | 1-y TAVR Mortality Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quartile of Baseline SAVR Mortality | .02 | .02 | ||

| 1 (Lowest mortality rate) | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| 2 | 1.02 (0.87-1.21) | .66 | 1.04 (0.92-1.17) | .52 |

| 3 | 1.13 (1.02-1.26) | .05 | 1.14 (1.02-1.28) | .02 |

| 4 (Highest mortality rate) | 1.23 (1.07-1.40) | .005 | 1.16 (1.05-1.28) | .01 |

| Transcatheter aortic valve replacement volume, per 10 procedures | 0.99 (0.99-0.997) | .001 | 0.996 (0.994-0.999) | .01 |

| Age, y | 1.03 (1.03-1.04) | <.001 | 1.02 (1.02-1.02) | <.001 |

| Female | 1.04 (0.96-1.13) | .30 | 0.79 (0.76-0.83) | <.001 |

| Number of hospital beds | 1.00 (0.999-1.00) | .41 | 1.00 (0.999-1.00) | .61 |

| Teaching hospital status | 0.96 (0.82-1.13) | .69 | 1.01 (0.90-1.13) | .92 |

| Elixhauser Comorbidity Index scores | 1.25 (1.22-1.27) | <.001 | 1.27 (1.25-1.28) | <.001 |

| Transapical access | 1.68 (1.52-1.85) | <.001 | 1.28 (1.20-1.37) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; SAVR, surgical aortic valve replacement; TAVR, trancatheter aortic valve replacement.

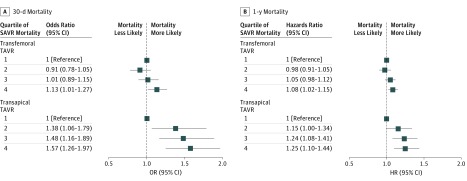

In subgroup analyses stratified by transfemoral vs transapical access sites, we found that higher baseline hospital SAVR mortality rates continued to be associated with higher 30-day mortality in transfemoral procedures (ORs: quartile 2, 0.91 [95% CI, 0.78-1.05]; quartile 3, 1.01 [95% CI, 0.89-1.15]; quartile 4, 1.13 [95% CI, 1.01-1.27]; P = .02) and transapical procedures (ORs: quartile 2, 1.38 [95% CI, 1.06-1.79]; quartile 3, 1.48 [95% CI, 1.16-1.89]; quartile 4, 1.57 [95% CI, 1.26-1.97]; P < .001). The same was true for 1-year mortality in transfemoral procedures (ORs: quartile 2, 0.98 [95% CI, 0.91-1.05]; quartile 3, 1.05 [95% CI, 0.98-1.12]; quartile 4, 1.08 [95% CI, 1.02-1.15]; P = .01) and transapical procedures (ORs: quartile 2, 1.15 [95% CI, 1.00-1.34]; quartile 3, 1.24 [95% CI, 1.08-1.41]; quartile 4, 1.25 [95% CI, 1.10-1.44]; P = .002; Figure 3). The association between baseline hospital SAVR mortality and TAVR mortality was stronger for transapical TAVR at 30 days than transfemoral TAVR (interaction P = .048), but these values were not significantly different at 1 year (interaction P = .11).

Figure 3. Adjusted Association Between Hospital Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement (SAVR) Mortality Quartile and Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement (TAVR) Mortality, Stratified by TAVR Access Site.

Discussion

While SAVR has long been the mainstay of treatment for severe aortic valve disease, TAVR has now surpassed SAVR in both the United States and Europe as the predominant treatment for severe symptomatic aortic stenosis.15,16,17 Because of the importance of cardiac surgical care and setting in the performance of TAVR, we hypothesized that the existence of higher-quality surgical programs may have been associated with better outcomes on their establishment of new TAVR programs. In this study, we demonstrated that hospitals with higher risk-adjusted mortality after SAVR prior to TAVR approval did indeed have higher short-term and long-term mortality for TAVR during the early phase of TAVR introduction and growth in the United States. This association between baseline SAVR quality and subsequent TAVR outcomes persisted after adjustment for hospital TAVR volume, which has a powerful association with TAVR outcomes,18 as well as patient comorbidities and other hospital characteristics.

Recent guidelines on the management of aortic valve disease have positioned the heart valve team at the center of the decision-making process for the assessment of patients with aortic valve stenosis.6,7 Ideally, members of the heart valve team should work in a coordinated manner to select the most beneficial treatment for each patient, manage procedural decisions, and coordinate postprocedural care. Surgical teams and units remain integral to many TAVR programs, and the most severe complications of TAVR, including aortic dissection, left ventricle perforation, and valve embolization or migration, may require emergency surgery.19

Hospitals with better SAVR quality as measured by lower risk-adjusted mortality rates may have subsequently had lower TAVR mortality for a number of reasons. First, higher-quality surgical programs may have had better patient selection, more highly functioning operating theaters (where TAVRs are commonly performed, particularly early after approval), and better-quality cardiac surgical care units. Additionally, subgroup analyses showed that patients undergoing transapical procedures in particular might have benefited from using higher-quality surgical centers.

Limitations

The current study has several limitations worth noting. First, the study is retrospective and based on administrative data and is therefore subject to residual confounding owing to unmeasured variables as well as inaccuracies in coding. High-quality surgical programs may have been correlated with improved systems of care and not directly associated with better TAVR outcomes. Second, because claims data represent billing diagnoses, they may not accurately reflect the presence and severity of clinical conditions. Institutions whose patients have more complex needs, based on comorbidities not available in claims data, may have artifactually lower risk-adjusted mortality rates for SAVR, TAVR, or both. Third, because of the limited granularity in the administrative dataset, we were not able to calculate traditional surgical risk scores, such as Society for Thoracic Surgery Predicted Risk of Mortality20 and logistic European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation.21 Another limitation is that we were not able to ascertain whether patients recovered in cardiac surgical intensive care units vs coronary care units. Finally, the observed patterns may not reflect overall patterns outside the United States and in US patients who are not Medicare beneficiaries.

Conclusions

Our findings may help inform professional societies currently updating recommendations for institutional and heart valve team requirements for TAVR. Patients, families, and referring clinicians need to make informed decisions regarding where they seek medical care, especially when that care involves a procedure with high complexity and major risks.

Hospitals with higher SAVR mortality rates in the pre-TAVR period also had higher short-term and long-term TAVR mortality rates after initiating TAVR programs. The quality of cardiac surgical care may be associated with a hospital’s performance with new structural heart disease programs. High-quality surgical programs were likely a critical component of successful TAVR programs, and this metric may shed light on the outcomes hospitals looking to develop new TAVR programs might achieve.

eTable 1. Exclusion criteria

eTable 2. Administrative codes used to define covariates

eTable 3. Observed 30-day and 1-year TAVR Mortality Rates after exclusion of hospitals performing fewer than 10 TAVRs during the study period among SAVR quality quartiles

References

- 1.Reardon MJ, Van Mieghem NM, Popma JJ, et al. ; SURTAVI Investigators . Surgical or transcatheter aortic-valve replacement in intermediate-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(14):1321-1331. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1700456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mack MJ, Leon MB, Smith CR, et al. ; PARTNER 1 trial investigators . 5-year outcomes of transcatheter aortic valve replacement or surgical aortic valve replacement for high surgical risk patients with aortic stenosis (PARTNER 1): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9986):2477-2484. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60308-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thourani VH, Kodali S, Makkar RR, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve replacement versus surgical valve replacement in intermediate-risk patients: a propensity score analysis. Lancet. 2016;387(10034):2218-2225. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30073-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baron SJ, Arnold SV, Wang K, et al. ; PARTNER 2 Investigators . Health status benefits of transcatheter vs surgical aortic valve replacement in patients with severe aortic stenosis at intermediate surgical risk: results from the PARTNER 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2(8):837-845. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2017.2039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kapadia SR, Tuzcu EM, Makkar RR, et al. Long-term outcomes of inoperable patients with aortic stenosis randomly assigned to transcatheter aortic valve replacement or standard therapy. Circulation. 2014;130(17):1483-1492. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.009834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, et al. 2017 AHA/ACC focused update of the 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(2):252-289. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Falk V, Baumgartner H, Bax JJ, et al. ; ESC Scientific Document Group . 2017 ESC/EACTS guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2017;52(4):616-664. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezx324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Culler SD, Cohen DJ, Brown PP, et al. Trends in aortic valve replacement procedures between 2009 and 2015: has transcatheter aortic valve replacement made a difference? Ann Thorac Surg. 2018;105(4):1137-1143. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2017.10.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krumholz HM, Nuti SV, Downing NS, Normand SL, Wang Y. Mortality, hospitalizations, and expenditures for the medicare population aged 65 years or older, 1999-2013. JAMA. 2015;314(4):355-365. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.8035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schermerhorn ML, Buck DB, O’Malley AJ, et al. Long-term outcomes of abdominal aortic aneurysm in the Medicare population. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(4):328-338. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1405778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schermerhorn ML, O’Malley AJ, Landon BE. Long-term outcomes of abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(21):2088-2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moore BJ, White S, Washington R, Coenen N, Elixhauser A. Identifying increased risk of readmission and in-hospital mortality using hospital administrative data: the AHRQ Elixhauser Comorbidity Index. Med Care. 2017;55(7):698-705. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kundi H, Strom JB, Valsdottir LR, et al. Trends in isolated surgical aortic valve replacement according to hospital-based transcatheter aortic valve replacement volumes. [published October 12, 2018]. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;pii: S1936-8798(18)31437-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2018.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rabe-Hesketh S, Skrondal A. Multilevel and Longitudinal Modeling Using Stata. College Station, Texas: STATA press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grover FL, Vemulapalli S, Carroll JD, et al. ; STS/ACC TVT Registry . 2016 annual report of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons/American College of Cardiology Transcatheter Valve Therapy Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(10):1215-1230. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Backer O, Luk NH, Olsen NT, Olsen PS, Søndergaard L. Choice of treatment for aortic valve stenosis in the era of transcatheter aortic valve replacement in Eastern Denmark (2005 to 2015). JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9(11):1152-1158. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2016.02.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eggebrecht H, Mehta RH. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) in Germany 2008-2014: on its way to standard therapy for aortic valve stenosis in the elderly? EuroIntervention. 2016;11(9):1029-1033. doi: 10.4244/EIJY15M09_11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carroll JD, Vemulapalli S, Dai D, et al. Procedural experience for transcatheter aortic valve replacement and relation to outcomes: the STS/ACC TVT registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(1):29-41. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.04.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eggebrecht H, Vaquerizo B, Moris C, et al. ; European Registry on Emergent Cardiac Surgery during TAVI (EuRECS-TAVI) . Incidence and outcomes of emergent cardiac surgery during transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI): insights from the European Registry on Emergent Cardiac Surgery during TAVI (EuRECS-TAVI). Eur Heart J. 2018;39(8):676-684. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Brien SM, Shahian DM, Filardo G, et al. ; Society of Thoracic Surgeons Quality Measurement Task Force . The Society of Thoracic Surgeons 2008 cardiac surgery risk models: part 2—isolated valve surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88(1)(suppl):S23-S42. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.05.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nashef SA, Roques F, Michel P, Gauducheau E, Lemeshow S, Salamon R; Euro SCORE Study Group . European system for cardiac operative risk evaluation (Euro SCORE). Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1999;16(1):9-13. doi: 10.1016/S1010-7940(99)00134-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Exclusion criteria

eTable 2. Administrative codes used to define covariates

eTable 3. Observed 30-day and 1-year TAVR Mortality Rates after exclusion of hospitals performing fewer than 10 TAVRs during the study period among SAVR quality quartiles