Abstract

This study uses the most recent national data available from Medicare and the Department of Veterans Affairs to quantify the savings Medicare Part D would achieve if it paid the same prices for prescription drugs currently paid by the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Several state and federal efforts to reduce prescription drug costs have proposed using the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) as a model, given its ability to obtain deep discounts on medications through direct negotiation with pharmaceutical manufacturers and the use of a national formulary. Published studies using data from a decade ago estimated that Medicare Part D could save $14 billion to $22 billion annually if it paid prices similar to those paid by the VA,1,2,3 and a recent congressional report4 for 20 brand-name drugs estimated potential annual savings of $2 billion. However, none of these estimates used actual prices paid by the VA, which can be lower than published federal prices. Thus, we used the most recent national data available from Medicare and the VA to quantify the savings Medicare Part D would achieve if it paid the same prices for prescription drugs currently paid by the VA.

Methods

We analyzed publicly available Medicare Part D prescription data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services between January 1, 2011, and December 31, 2016.5 We obtained gross Medicare spending on each medication (defined based on the generic product name), quantity dispensed, and number of claims. We excluded drugs that had formulations other than capsules and tablets to accurately calculate per-unit costs and limited our analyses to the top 50 oral drugs dispensed based on Medicare spending. This project using deidentified data was exempted from institutional review board approval by the Veterans Affairs St Louis Health Care System.

To make Medicare and VA prescription spending comparable, we made 2 adjustments to Medicare spending. First, because publicly reported Medicare Part D data include patient payments and do not account for rebates, we discounted annual gross Medicare spending to account for these factors (eAppendix in the Supplement). Second, we subtracted a $2.50 dispensing fee for each Medicare claim because VA drug spending data do not include these costs.6 After these adjustments, medication spending was divided by the number of units dispensed to establish a Medicare per unit cost.

Using the database of all prescriptions dispensed by the VA from 2011 to 2016, we identified all matches for the Medicare medications and obtained comparable data on acquisition costs and quantity dispensed using the actual price paid by the VA. We then applied the per unit costs from the VA to Medicare to calculate the amount that Medicare would spend annually if it obtained VA prices for the same quantity of medications.

Results

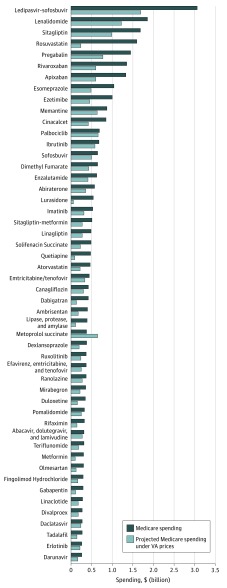

Annual net Medicare Part D spending on the top 50 oral drugs ranged from $26.3 billion in 2011 to $32.5 billion in 2016 (Table). In 2016, if Medicare Part D obtained VA prices, the cost of these medications would have been $18.0 billion, representing savings of $14.4 billion, or an estimated 44%. The projected magnitude of estimated annual savings from 2011 to 2015 was similar, ranging from 38% to 50%. The Figure shows actual Medicare Part D spending in 2016 for these 50 drugs and spending if Medicare obtained VA prices.

Table. Net Medicare Part D Spending on Top 50 Oral Medications and Potential Savings If Substituting Prices From Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), 2011-2016a.

| Year | Net Medicare Spending, $b | Net Medicare Spending on Top 50 Medications, $b | Medicare Spending on Top 50 Medications With VA Price, $ | Potential Savings on Top 50 Medications With VA Price, $ | Potential Savings as % of Top 50 Medication Spending | Average VA Unit Price as a % of Medicare Price |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 63 810 141 219 | 26 262 420 692 | 13 441 129 229 | 12 821 291 463 | 49 | 49 |

| 2012 | 63 613 064 596 | 24 673 379 757 | 12 405 375 641 | 12 268 004 115 | 50 | 50 |

| 2013 | 65 985 453 125 | 22 338 975 172 | 12 353 820 052 | 9 985 155 120 | 45 | 56 |

| 2014 | 74 157 510 206 | 25 387 937 019 | 15 849 390 027 | 9 538 546 992 | 38 | 64 |

| 2015 | 85 774 056 349 | 29 973 101 817 | 17 882 760 557 | 12 090 341 260 | 40 | 63 |

| 2016 | 95 812 067 756 | 32 476 449 134 | 18 032 239 033 | 14 444 210 101 | 44 | 58 |

| Total | 449 152 293 251 | 161 112 263 591 | 89 964 714 539 | 71 147 549 051 | NA | NA |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Medicare Part D spending was obtained from publicly reported data and excludes drugs available in formulations other than capsules or tablets. Department of Veterans Affairs spending data for these medications was obtained from the VA national patient care databases. All spending figures are nominal dollars.

Net spending in Medicare accounts for rebates and dispensing costs.

Figure. Actual Medicare Part D Spending on Top 50 Oral Drugs in 2016 and Projected Spending Using Department of VA Prices.

Medicare Part D spending was obtained from publicly reported data; Veterans Affairs (VA) spending data for these medications was obtained from VA national patient care databases; and VA prices for metoprolol succinate exceeded those in Medicare during 2016 because of VA contracting issues.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the most up-to-date analysis that directly compares prices between Medicare Part D and the VA, accounting for estimated rebates and using actual VA prices as opposed to publicly reported federal supply schedule prices. Using these data, we calculated $14.4 billion in potential savings in 2016 for only 50 drugs.

There are important limitations to this study. First, we did not differentiate between dosages or long-acting formulations when calculating unit prices, but most medications were brand-only products and were typically priced similarly regardless of dose. Second, it is unlikely that Medicare could capture the entirety of these savings, as VA prices could increase once Medicare obtained access, and Medicare would likely require a national formulary to leverage these reductions in price. However, our analysis of potential savings is conservative by studying only 50 drugs, omitting many high-cost medications with injectable formulations (eg, insulin and adalimumab), and focusing on price only without accounting for changes in use that could also lead to savings.

eAppendix. Methods

References

- 1.Frakt AB, Pizer SD, Hendricks AM. Controlling prescription drug costs: regulation and the role of interest groups in Medicare and the Veterans Health Administration. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2008;33(6):1079-1106. doi: 10.1215/03616878-2008-032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gellad WF, Schneeweiss S, Brawarsky P, Lipsitz S, Haas JS. What if the federal government negotiated pharmaceutical prices for seniors? an estimate of national savings. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(9):1435-1440. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0689-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frakt AB, Pizer SD, Feldman R. Should Medicare adopt the Veterans Health Administration formulary? Health Econ. 2012;21(5):485-495. doi: 10.1002/hec.1733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Senate Homeland Security & Governmental Affairs Committee Manufactured crisis: how better negotiation could save billions for Medicare and America’s seniors: report two. https://www.hsgac.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/REPORT-Manufactured%20Crisis-How%20Better%20Negotiation%20Could%20Save%20Billions%20for%20Medicare%20and%20America's%20Seniors.pdf. Accessed August 12, 2018.

- 5.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Medicare Part D drug spending dashboard & data. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Information-on-Prescription-Drugs/MedicarePartD.html. Accessed May 20, 2018.

- 6.Lieberman SM, Ginsburg PB Would price transparency for generic drugs lower costs for payers and patients? https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/es_20170613_genericdrugpricing.pdf. Published June 2017. Accessed May 20, 2018.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix. Methods