This cohort study uses data from the Premier Inpatient Database to assess outcomes associated with the addition of antibiotic treatment in patients hospitalized for asthma exacerbation treated with corticosteroids who had no other indication for antibiotic therapy.

Key Points

Question

Among patients hospitalized for an asthma exacerbation and treated with corticosteroids, does the addition of antibiotic therapy result in better outcomes?

Findings

In this cohort study of 19 811 patients hospitalized for an asthma exacerbation treated with corticosteroids, 8788 (44%) received antibiotics during the first 2 days of hospitalization. Compared with patients who were not treated with antibiotics, treated patients had a significantly longer hospital stay, similar rate of treatment failure, and higher risk of antibiotic-related diarrhea.

Meaning

Antibiotic treatment may not be associated with better outcomes and should not be prescribed routinely in adult patients hospitalized for asthma treated with corticosteroids.

Abstract

Importance

Although professional society guidelines discourage use of empirical antibiotics in the treatment of asthma exacerbation, high antibiotic prescribing rates have been recorded in the United States and elsewhere.

Objective

To determine the association of antibiotic treatment with outcomes among patients hospitalized for asthma and treated with corticosteroids.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Retrospective cohort study of data of 19 811 adults hospitalized for asthma exacerbation and treated with systemic corticosteroids in 542 US acute care hospitals from January 1, 2015, through December 31, 2016.

Exposures

Early antibiotic treatment, defined as an treatment with an antibiotic initiated during the first 2 days of hospitalization and prescribed for a minimum of 2 days.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome measure was hospital length of stay. Other measures were treatment failure (initiation of mechanical ventilation, transfer to the intensive care unit after hospital day 2, in-hospital mortality, or readmission for asthma) within 30 days of discharge, hospital costs, and antibiotic-related diarrhea. Multivariable adjustment, propensity score matching, propensity weighting, and instrumental variable analysis were used to assess the association of antibiotic treatment with outcomes.

Results

Of the 19 811 patients, the median (interquartile range [IQR]) age was 46 (34-59) years, 14 389 (72.6%) were women, 8771 (44.3%) were white, and Medicare was the primary form of health insurance for 5120 (25.8%). Antibiotics were prescribed for 8788 patients (44.4%). Compared with patients not treated with antibiotics, treated patients were older (median [IQR] age, 48 [36-61] vs 45 [32-57] years), more likely to be white (48.6% vs 40.9%) and smokers (6.6% vs 5.3%), and had a higher number of comorbidities (eg, congestive heart failure, 6.2% vs 5.8%). Those treated with antibiotics had a significantly longer hospital stay (median [IQR], 4 [3-5] vs 3 [2-4] days) and a similar rate of treatment failure (5.4% vs 5.8%). In propensity score–matched analysis, receipt of antibiotics was associated with a 29% longer hospital stay (length of stay ratio, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.27-1.31) and higher cost of hospitalization (median [IQR] cost, $4776 [$3219-$7373] vs $3641 [$2346-$5942]) but with no difference in the risk of treatment failure (propensity score–matched OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.82-1.11). Multivariable adjustment, propensity score weighting, and instrumental variable analysis as well as several sensitivity analyses yielded similar results.

Conclusions and Relevance

Antibiotic therapy may be associated with a longer hospital length of stay, higher hospital cost, and similar risk of treatment failure. These results highlight the need to reduce inappropriate antibiotic prescribing among patients hospitalized for asthma.

Introduction

Asthma is the most common chronic lung condition in United States, where it affects 24.6 million individuals.1 Asthma exacerbations are responsible for 1.7 million emergency department visits, 440 000 hospitalizations, and more than $50 billion in health care expenditures each year in the United States.1 Current guidelines for the treatment of patients hospitalized for an asthma exacerbation call for objective assessment of lung function, controlled oxygen administration, inhaled short-acting β2-agonist bronchodilators, and systemic corticosteroids, but several studies have documented limited adherence to these guidelines and variation in acute and chronic asthma care.2,3 Although recent reviews published in the Cochrane database have not found sufficient evidence in favor of antimicrobial treatment in asthma exacerbations and current guidelines recommend against routine use of antibiotic therapy,4 inappropriate use of antibiotics has been documented in several countries including the United States. In a recent study of a large national sample, we found that nearly 49.1% of patients hospitalized for asthma received treatment with antibiotics in the absence of documentation of an indication for antibiotic therapy.5

The evidence surrounding use of antibiotics in patients with asthma is limited.6,7 The most recent trial, Azithromycin Against Placebo for Acute Exacerbations of Asthma, showed no benefit of short-term treatment with azithromycin when added to a regimen of oral or intravenous corticosteroids.7 Critics question the external validity of the trial and whether the lack of benefit was a result of the fact that patients who could have benefited from an antibiotic had already received one and were therefore not enrolled. In the absence of more definitive information from randomized clinical trials, we sought to evaluate the association between use of antibiotics when prescribed in addition to corticosteroids and outcomes among a large, representative sample of patients hospitalized for asthma exacerbation. We hypothesized that antibiotic therapy would not be associated with additional benefit.

Methods

Data Source, Setting, and Patients

We conducted a retrospective cohort study by using data collected from 543 acute care hospitals in the United States that participate in Premier Inpatient Database, an inpatient, enhanced administrative database developed for measuring health care quality and use. Participating hospitals are primarily small to medium-sized nonteaching hospitals located mostly in urban areas in all regions of the United States. In addition to the information contained in the standard hospital discharge file, such as the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes or International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes, hospital, and physician information, Premier includes a date-stamped log of all billed items, including medications dispensed and diagnostic tests performed. Approximately 75% of participating hospitals submit cost data; the rest submit calculated costs based on each hospital’s specific cost to charge ratio.8 The institutional review board at Baystate Medical Center, Springfield, Massachusetts, approved the study, which was not considered human subjects research because the data set does not contain any identifiable patient information.

We included patients 18 years or older who were admitted to the hospital from January 1, 2015, through December 31, 2016, for a principal diagnosis of asthma or a principal diagnosis of acute respiratory failure combined with a secondary diagnosis of asthma (we used ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM diagnostic codes in accordance with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services definition).9 We restricted analysis to patients treated with systemic corticosteroids (oral or intravenous corticosteroids) at a dosage equivalent to 20 mg/d of prednisone, because systemic corticosteroids are recommended for patients with moderate to severe asthma exacerbation. We excluded patients with a potential indication for antibiotic therapy, including those with a secondary diagnosis of acute or chronic bronchitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, emphysema, or bronchiectasis; those with a diagnosis of sinusitis, sepsis, pneumonia, urinary tract infection, or skin or soft-tissue infection present on admission; and patients with a blood or sputum culture at the time of admission. In addition, we excluded patients transferred from another acute care hospital because we did not know whether they were treated with antibiotics before arrival as well as patients transferred to another hospital because we could not ascertain their outcomes. If a patient had more than 1 eligible admission during the period of the study, we randomly selected 1 admission to avoid survival bias.

Early antibiotic treatment was defined as antibiotic therapy initiated during the first 2 days of hospitalization and prescribed for a minimum of 2 days. Antibiotics were grouped based on previously published results4 into the following categories: macrolides, quinolones, cephalosporins, and tetracyclines. In our primary analysis, patients with antibiotic treatment started after day 2 of hospitalization were grouped with those not treated because late treatment may be a marker of patient deterioration, which can be associated with the decision to not use antibiotic therapy at the time of admission.

Outcomes

Our primary outcome was hospital length of stay measured in days. Our main secondary outcome was a composite measure of treatment failure defined as initiation of invasive or noninvasive mechanical ventilation, transfer to the intensive care unit after hospital day 2, in-hospital mortality, or readmission for asthma exacerbation within 30 days of discharge.10 We also examined hospital cost and potential adverse effects of antibiotic use, including allergic reactions and antibiotic-associated diarrhea defined as treatment with metronidazole or oral vancomycin hydrochloride initiated after hospital day 3 or readmission within 30 days for diarrhea or Clostridium difficile infection.

Other Treatments and Patient Factors

In addition to patient demographic characteristics, primary payer, and principal diagnosis, we classified comorbidities by using the comorbidity score as described by Gagne et al.11 The score was devised to predict mortality and 30-day readmissions and has better predictive ability than Elixhauser or Charlson scores. We also examined medications typically used in the treatment of asthma exacerbation, including short- and long-acting bronchodilators and methylxanthines, and medications used for smoking cessation therapy. We counted the number of admissions for asthma in the previous year as a proxy for asthma severity and degree of control.

Statistical Analysis

We compared the characteristics of patients with asthma who received early antibiotic therapy with those patients who did not receive antibiotics (including patients in whom antibiotics were prescribed later in the hospital stay) using absolute standardized differences; a difference greater than 10% is considered meaningful.12 To estimate the association of antibiotic therapy with length of hospital stay, treatment failure, total cost, and other outcomes, we developed a multivariable predictive model as a function of patient, treatment, and hospital characteristics. Logit link functions were used for the treatment failure outcomes and the identity link for length of stay and cost. To further reduce the threat of confounding by indication (in which patients with the most clinically severe asthma presentations would be the most likely to receive antibiotics), we developed a propensity score for early antibiotic treatment by using all patient characteristics, early treatments, comorbidities, and selected interaction terms. We matched patients who did not receive antibiotic treatment with those with similar propensity who received antibiotics, and we carried out a conditional logistic regression analysis after accounting for the match.13,14 Unadjusted (accounting for clustering), covariate-adjusted, and propensity score–adjusted models for each outcome were evaluated. In addition, we used standardized mortality ratio weighting to obtain estimates of average treatment effect among treated patients.15 To further address the threat of residual selection bias due to unmeasured confounders not addressed through propensity adjustment, we performed an instrumental variable analysis. We used a grouped-treatment approach, a form of instrumental variable analysis in which all patients treated at the same hospital are assigned a probability of treatment with an antibiotic equal to the overall treatment rate at that hospital. This grouped rate was substituted for individual patient exposure to treatment in the logistic regression model. Grouping treatment at the hospital level bypasses the issue of confounding by indication while still accounting for patient-level covariates and outcomes.16

We performed several sensitivity analyses. First, we excluded patients in whom antibiotic therapy was initiated after day 2 of hospitalization from the nontreated group. Second, we limited the sample to nonsmokers younger than 70 years who were not treated with mechanical ventilation or admitted to the intensive care unit within 2 days of admission to further exclude patients for whom administration of antibiotics may be considered more acceptable in light of the severity of presentation and the difficulty differentiating chronic obstructive pulmonary disease from asthma. Furthermore, because macrolides were the most frequently used antibiotics, we compared the outcomes within the following 2 groups: patients treated with a macrolide alone vs those not treated with antibiotics and patients treated with a macrolide alone vs those treated with any other antibiotic.

For each model, adjusted odds ratios (ORs) for treatment failure or ratios of hospital length of stay and cost with associated 95% CIs for antibiotic treatment were calculated. All tests of significance were 2-sided. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

A total of 19 811 patients met all the inclusion criteria (eFigure in the Supplement). The median (interquartile range [IQR]) age of these patients was 46 (34-59) years; 14 389 (72.6%) were women, 8771 (44.3%) were white, and Medicare was the primary form of health insurance for 5120 (25.8%). Among the entire cohort, the most frequent comorbidities were hypertension (8917 [45.0%]), obesity (5699 [28.8%]), diabetes (4459 [22.5%]), and depression (2557 [12.9%]). Of the cohort, 3060 (15.5%) were admitted at least once in the previous year (Table 1). Median (IQR) length of stay was 3 (2-4) days; in-hospital mortality occurred in 32 patients (0.2%), 237 (1.2%) of the patients were intubated after day 2, and 1104 (5.6%) experienced the combined outcome of treatment failure (Table 2).

Table 1. Selected Patient Characteristics and Treatments.

| Characteristic | All Patients (N = 19 811) | Entire Cohort | Propensity Score–Matched Cohort | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early AB Therapy (n = 8788)a | Late or No AB Therapy (n = 11 023) | Early AB Therapy (n = 6833)a | Late or No AB Therapy (n = 6833) | ||

| Age, median (IQR), yb | 46 (34-59) | 48 (36-61) | 45 (32-57) | 46 (34-59) | 47 (34-60) |

| Female, No. (%)b | 14 389 (72.6) | 6677 (76.0) | 7712 (70.0) | 5022 (73.5) | 5118 (74.9) |

| Race, No. (%)b | |||||

| White | 8771 (44.3) | 4268 (48.6) | 4503 (40.9) | 3086 (45.2) | 3182 (46.6) |

| Black | 6242 (31.5) | 2480 (28.2) | 3762 (34.1) | 2126 (31.1) | 2031 (29.7) |

| Hispanic | 2165 (10.9) | 937 (10.7) | 1228 (11.1) | 723 (10.6) | 734 (10.7) |

| Otherc | 2633 (13.3) | 1103 (12.6) | 1530 (13.9) | 898 (13.1) | 886 (13.0) |

| Insurance, No. (%)b | |||||

| Medicare | 5120 (25.8) | 2581 (29.4) | 2539 (23.0) | 1774 (26.0) | 1852 (27.1) |

| Medicaid | 5519 (27.9) | 2186 (24.9) | 3333 (30.2) | 1853 (27.1) | 1746 (25.6) |

| Private | 6173 (31.2) | 2745 (31.2) | 3428 (31.1) | 2156 (31.6) | 2214 (32.4) |

| Uninsured | 2239 (11.8) | 972 (11.1) | 1367 (12.4) | 825 (12.1) | 803 (11.8) |

| Unknown | 660 (3.3) | 304 (3.5) | 356 (3.2) | 225 (3.3) | 218 (3.2) |

| Principle diagnosis, No. (%)b | |||||

| Asthma | 17 735 (89.5) | 7708 (87.7) | 10 027 (91.0) | 6133 (89.8) | 6080 (89.0) |

| Acute respiratory failure | 2076 (10.5) | 1080 (12.3) | 996 (9.0) | 700 (10.2) | 753 (11.0) |

| Gagne score, median (IQR)d | 1 (1-2) | 1 (1-2) | 1 (1-2) | 1 (1-2) | 1 (1-2) |

| Comorbidity, No. (%)e | |||||

| Congestive heart failure | 1179 (6.0) | 544 (6.2) | 635 (5.8) | 411 (6.0) | 397 (5.8) |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 2181 (11.0) | 1119 (12.7) | 1062 (9.6) | 738 (10.8) | 792 (11.6) |

| Hypertensionb | 8917 (45.0) | 4283 (48.7) | 4634 (42.0) | 3090 (45.2) | 3154 (46.2) |

| Diabetes | 4459 (22.5) | 2172 (24.7) | 2287 (20.8) | 1532 (22.4) | 1595 (23.3) |

| Renal failure | 831 (4.2) | 411 (4.7) | 420 (3.8) | 280 (4.1) | 297 (4.4) |

| Obesityb | 5699 (28.8) | 2765 (31.5) | 2934 (26.6) | 2016 (29.5) | 2053 (30.1) |

| Depression | 2557 (12.9) | 1194 (13.6) | 1363 (12.4) | 911 (13.3) | 887 (13.0) |

| Therapies and tests, No. (%) | |||||

| Long anticholinergic therapy | 725 (3.7) | 361 (4.1) | 364 (3.3) | 269 (3.9) | 219 (3.2) |

| Short-acting β-agonist therapy | 17 391 (87.8) | 7771 (88.4) | 9620 (87.3) | 5983 (87.6) | 6026 (88.2) |

| Long-acting β-agonist therapy | 4486 (22.6) | 1976 (22.5) | 2510 (22.8) | 1559 (22.8) | 1501 (22.0) |

| Methylxanthine therapy | 472 (2.4) | 245 (2.8) | 227 (2.1) | 181 (2.7) | 159 (2.3) |

| Arterial blood gas test | 5454 (27.5) | 2412 (27.5) | 3042 (27.6) | 1881 (27.5) | 1930 (28.3) |

| Early antibiotic therapy, No. (%)d | |||||

| All antibiotics | 8788 (44.4) | 8788 (100.0) | NA | 6833 (100.0) | NA |

| Macrolides | 4558 (23.0) | 4558 (51.9) | NA | 3626 (53.1) | NA |

| Quinolones | 3059 (15.4) | 3059 (34.8) | NA | 2308 (33.8) | NA |

| Third-generation cephalosporins | 1719 (8.7) | 1719 (19.6) | NA | 1245 (18.2) | NA |

| Tetracyclines | 1016 (5.1) | 1016 (11.6) | NA | 767 (11.2) | NA |

| Otherf | 603 (3.0) | 603 (6.9) | NA | 473 (6.9) | NA |

| Mechanical ventilation, No. (%) | |||||

| Noninvasive | 2347 (11.9) | 1025 (11.7) | 1322 (12.0) | 815 (11.9) | 825 (12.1) |

| Invasive | 773 (3.9) | 342 (3.9) | 431 (3.9) | 287 (4.2) | 277 (4.1) |

Abbreviations: AB, antibiotic; IQR, interquartile range; NA, not applicable.

Antibiotic therapy started within 2 days of hospitalization.

Standardized difference is greater than 0.1.

Unknown race or nonblack, nonwhite, non-Hispanic (not defined separately).

For an explanation of the Gagne score, see the Other Treatments and Patient Factors subsection of the Methods section.

Additional comorbidities evaluated in models but not reported in tables include valvular disease, pulmonary circulation disease, peripheral vascular disease, paralysis, other neurological disorders, hypothyroidism, liver disease, peptic ulcer disease excluding bleeding, AIDS, lymphoma, metastatic cancer, rheumatoid arthritis or collagen vascular disease, coagulopathy, weight loss, fluid and electrolyte disorders, chronic blood loss anemia, deficiency anemias, alcohol abuse, drug abuse, and psychoses.

Any other classes of antibiotics, including first- and second-generation cephalosporins, aminoglycoside, penicillins, carbapenems, and β-lactamase inhibitor combinations.

Table 2. Unadjusted Outcomes of Patients Hospitalized for Asthma Exacerbation.

| Outcome | All Patients (N = 19 811) | Entire Cohort | Propensity Score–Matched Cohort | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early AB Therapy (n = 8788)a | Late or No AB Therapy (n = 11 023) | Early AB Therapy (n = 6833)a | Late or No AB Therapy (n = 6833) | ||

| Hospital length of stay, median (IQR), db,c | 3 (2-4) | 4 (3-5) | 3 (2-4) | 4 (3-5) | 3 (2-4) |

| Treatment failure, No. (%) | 1104 (5.6) | 470 (5.4) | 634 (5.8) | 373 (5.5) | 388 (5.7) |

| In-hospital mortality, No. (%) | 32 (0.2) | 18 (0.2) | 14 (0.1) | 14 (0.2) | 11 (0.2) |

| Late mechanical ventilation (after day 3), No. (%)b | 237 (1.2) | 125 (1.4) | 112 (1.0) | 94 (1.4) | 89 (1.3) |

| Transfer to intensive care unit, No. (%) | 76 (0.4) | 40 (0.5) | 36 (0.3) | 33 (0.5) | 31 (0.5) |

| Total cost, median (IQR) US$b,c | 4129 (2647-6588) | 4911 (3283-7478) | 3537 (2251-5789) | 4776 (3219-7373) | 3641 (2346-5942) |

| Diarrhea, No. (%)b | 225 (1.1) | 134 (1.5) | 91 (0.8) | 98 (1.4) | 75 (1.1) |

| Asthma readmission within 30 d, No. (%)b | 801 (4.1) | 305 (3.5) | 496 (4.5) | 248 (3.6) | 277 (4.1) |

| All cause 30-d readmission, No. (%)d | 1846 (9.3) | 805 (9.2) | 1041 (9.5) | 614 (9.0) | 654 (9.6) |

Abbreviations: AB, antibiotic; IQR, interquartile range.

Antibiotic therapy started within 2 days of hospitalization.

Two-sided P value for the cohort is less than .01.

Two-sided P value for the matched cohort is less than .01.

Readmissions are calculated among survivors.

Overall, 8788 patients (44.4%) received antibiotics during the first 2 hospital days, and the most frequently prescribed antibiotics were macrolides (4558 patients [51.9%]), quinolones (3059 [34.8%]), and third-generation cephalosporins (1719 [19.6%]). An additional 598 patients (3.0%) received antibiotics at some point after hospital day 2. Compared with patients who did not receive early antibiotic therapy, treated patients were older (median [IQR] age, 48 [36-61] vs 45 [32-57] years), more likely to be white (48.6% vs 40.9%), and more likely to have Medicare insurance (29.4% vs 23.0%). They were also more likely to have a diagnosis of acute respiratory failure (12.3% vs 9.0%), to receive smoking cessation therapy (6.6% vs 5.3%), and to have comorbid diagnoses of congestive heart failure (6.2% vs 5.8%), chronic pulmonary disease (12.7% vs 9.6%), diabetes (24.7% vs 20.8%), renal failure (4.7 vs 3.8%), obesity (31.5% vs 26.6%), and depression (13.6% vs 12.4%). Of all the patients, 470 (5.4%) in the early antibiotic therapy group experienced treatment failure compared with 634 (5.8%) who did not receive early antibiotic therapy (Table 1).

A total of 6833 patients treated with antibiotics during the first 2 hospital days were successfully matched to patients with a similar propensity score who did not receive antibiotics by hospital day 2, and most patient characteristics were balanced. Three hundred seventy-three patients (5.5%) in the early antibiotic therapy group experienced treatment failure compared with 388 patients (5.7%) who did not receive early antibiotic therapy (P = .58), and the median (IQR) length of stay in the early antibiotic therapy group was 4 (3-5) days vs 3 (2-4) days in the untreated group (P < .001). In the early antibiotic–treated group, 98 patients (1.4%) had a diagnosis of antibiotic-associated diarrhea compared with 75 (1.1%) in the untreated group (Table 2).

Results From Multivariable, Propensity Score–Matched Cohort and Grouped Treatment Approach Analyses

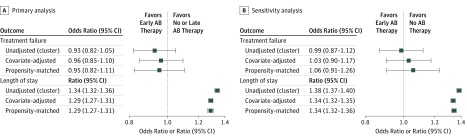

Treatment with antibiotics was associated with a longer hospital stay and higher hospitalization costs in all multivariable analyses, including the propensity score–matched cohort (length of stay ratio, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.27-1.31 [Figure]; median [IQR] cost [in US $], $4776 [$3219-$7373] vs $3641 [$2346-$5942]); OR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.28-1.33). In the analysis accounting for clustering of patients within hospital and adjusted for other variables, the propensity score–matched cohort, and the standardized mortality ratio weighting analysis, there was no significant difference in the odds of treatment failure between groups (adjusted OR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.85-1.10; propensity score–matched OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.82-1.11). In the instrumental variable analysis, which used the hospital antibiotic prescribing rate (percentage of patients hospitalized with asthma who received antibiotics), the OR for 100% hospital rate vs 0% was 0.97 (95% CI, 0.66-1.43). All-cause 30-day readmissions among survivors were not different between the 2 groups (propensity score–matched analysis OR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.84-1.06), and the association remained nonsignificant in the group treatment analysis (OR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.99-1.004). There was no difference in 30-day readmissions for asthma between the groups (propensity score–matched analysis OR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.73-1.05). The risk for antibiotic-related diarrhea was higher in the antibiotic-treated patients (adjusted OR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.2-1.9), but the association became nonsignificant in the propensity score–matched cohort (adjusted OR, 1.34; 95% CI, 0.99-1.83). For all the above analyses, the standardized mortality ratio weighting produced similar results (not shown).

Figure. Unadjusted, Multivariable-Adjusted, and Propensity-Matched Analysis Results for Treatment Failure and Hospital Length of Stay.

A, Primary analysis in the cohort of patients treated with antibiotics (ABs) initiated during first 2 days of hospitalization and those not treated with ABs or in whom AB therapy was started after day 2. B, Sensitivity analysis in the cohort of patients treated with ABs initiated during first 2 days of hospitalization and those not treated with ABs. Error bars indicate odds ratio for treatment failure and ratio of length of stay.

Several sensitivity analyses were conducted. In the analysis that excluded patients treated with antibiotics after day 2, the results were similar to those from the primary analysis except that patients treated with antibiotics had 2.6 times greater risk of diarrhea than those not treated (OR, 2.6; 95% CI, 1.7-3.9). The main results remained consistent in the analysis restricted to nonsmokers younger than 70 years who did not have acute respiratory failure as the principal diagnosis and did not receive mechanical ventilation within 2 days of admission. Analyses that compared patients treated with macrolides only with those not treated with antibiotics and compared those treated with macrolides with those treated with other antibiotics produced similar results in regard to treatment failure and cost. Patients treated with macrolides only were significantly less likely to have antibiotic-related diarrhea than those treated with other antibiotics (1.1% vs 2.0%; P < .001).

Discussion

In this observational study of nearly 20 000 patients hospitalized for asthma at more than 500 US hospitals, we found that, although use of antibiotics during the first 2 hospital days was common, antibiotic treatment was not associated with better patient outcomes. Instead, antibiotic treatment was associated with a longer hospital length of stay, higher hospital costs, and increased risk of antibiotic-related diarrhea. These results were consistent in multiple sensitivity analyses intended to reduce the possibility of selection bias and unmeasured confounders. These findings are novel, reflect the experience of unselected patients cared for in routine settings, and lend strong support to current guidelines that recommend against the use of antibiotics in the absence of concomitant infection. In addition, the findings highlight the need for future research to improve antimicrobial stewardship in the setting of asthma.

Evidence for the role of antibiotic treatment in patients with asthma exacerbation is limited and is derived from 6 trials of a total of 681 adults and children.17 Most trials analyzed resolution of symptoms or measurements of lung function and did not investigate outcomes, such as the need for mechanical ventilation, readmission, or death. One trial of 278 adults with asthma exacerbation treated for 10 days with telithromycin (Telithromycin in Acute Exacerbations of Asthma [TELICAST]) found that antibiotic-treated patients had greater reduction in symptoms but no change in peak expiratory flow or other outcomes; owing to adverse effects, use of this antibiotic has been discontinued in the United States.6 The most recent trial that compared the addition of azithromycin to standard treatment that included systemic corticosteroids (Azithromycin Against Placebo in Exacerbations of Asthma [AZALEA]) in 199 adults hospitalized for asthma did not show any benefit for symptoms. The difference in the results between the 2 trials could be related to the fact that only 34% of patients in the TELICAST study were treated with systemic corticosteroids. Our results confirm the lack of value of short-term treatment with antibiotics in addition to systemic corticosteroids in patients hospitalized for asthma exacerbation.

Inappropriate use of antibiotics is a public health problem given the risk of bacterial resistance and of antibiotic-related adverse events.18 Asthma exacerbations are an important cause of hospitalizations, and decreasing the inappropriate use of antibiotics fits well within the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Strategy for Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria.19,20 The discontinuation of ineffective, overused, or harmful interventions, or de-implementation, has emerged as a new area of inquiry in the field of dissemination and implementation science. Antibiotic treatment in patients with asthma exacerbation is an appropriate practice for deimplementation because it lacks evidence for effectiveness and it may be harmful. Validating known biomarkers, such as the procalcitonin level, for guiding targeted antibiotic therapy is one strategy that could influence clinicians’ willingness to refrain from prescribing antibiotics for patients with asthma.21 Two recent studies from China22,23 have shown that a procalcitonin-guided strategy for patients hospitalized for exacerbation of asthma reduced antibiotic prescription (48.9% for patients who received procalcitonin testing vs 87.8% of those who did not; P < .001) and antibiotic exposure (relative risk, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.44-0.70), with no differences in clinical recovery, hospital length of stay, number of asthma exacerbations, or number of hospital readmissions during the 12-month follow-up period.

Limitations

Although we controlled for potential confounders and used several analytic strategies, we cannot exclude the possibility of residual confounding by indication in which antibiotics would be preferentially given to patients with higher acuity of illness. To reduce this threat, we used robust statistical analyses, including propensity score matching, standardized mortality ratio weighting, and instrumental variable analysis, the last being a strategy to specifically reduce the risk of confounding from unmeasured factors. The results of the instrumental variable analysis were consistent with those of the primary analysis, lending support to our conclusions. We also performed several sensitivity analyses, which yielded the same results. Although our study was not designed to determine the reason for increased hospital length of stay among patients treated with antibiotics, one potential explanation is that some physicians may have delayed hospital discharge until a patient completed a course of antibiotics. Another possible explanation is that the increase in mean length of stay was a function of antibiotic-related diarrhea. Because this was an observational study, we recognize that our results show an association between the hospital length of stay and antibiotic treatment and do not demonstrate causality. A second limitation is that, given the nature of our data set, we did not have access to physiological measures of disease severity, such as the results of spirometry tests or information on patient symptoms. Nevertheless, our analyses accounted for previous hospital admission and other treatments as a measure of severity and were robust in several sensitivity analyses. Third, we did not have access to previous pulmonary function test results to confirm the diagnosis of asthma or its severity. We used a set of ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM diagnostic codes, which are recommended by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, and we included only patients treated with oral or intravenous corticosteroids. Excluding patients with a secondary diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease further strengthened our study, limiting the conclusions to patients for whom antibiotics were definitely not indicated. Of note, despite similar confounding by indication, an earlier study that assessed the association between antibiotic treatment and outcomes in patients hospitalized for exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease found that antibiotic treatment was associated with better outcomes.24 Finally, our study was restricted to inpatient events and 30-day readmission to the index hospital for patients hospitalized in the United States.

Conclusions

Among patients hospitalized for asthma exacerbation, antibiotic therapy was not associated with reduced risk of treatment failure but was associated with longer hospital length of stay, higher hospital costs, and risk of antibiotic-related diarrhea. Our results support current clinical guidelines that recommend against the use of antibiotics in the treatment of patients with asthma exacerbation. Further research is needed to develop and test deimplementation strategies to reduce inappropriate antibiotic prescribing for patients hospitalized for asthma.

eFigure. Flow Chart With Patients Excluded From the Cohort Analyzed

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention FastStats: asthma. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/asthma.htm. March 2017. Accessed April 16, 2018.

- 2.Mularski RA, Asch SM, Shrank WH, et al. The quality of obstructive lung disease care for adults in the United States as measured by adherence to recommended processes. Chest. 2006;130(6):1844-1850. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.6.1844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hasegawa K, Sullivan AF, Tsugawa Y, et al. ; MARC-36 Investigators . Comparison of US emergency department acute asthma care quality: 1997-2001 and 2011-2012. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135(1):73-80. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.08.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Global Initiative for Asthma Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. https://ginasthma.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/wms-GINA-2018-report-tracked_v1.3.pdf. Published 2015. Accessed April 16, 2018.

- 5.Lindenauer PK, Stefan MS, Feemster LC, et al. Use of antibiotics among patients hospitalized for exacerbations of asthma. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(9):1397-1400. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.4050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnston SL, Blasi F, Black PN, Martin RJ, Farrell DJ, Nieman RB; TELICAST Investigators . The effect of telithromycin in acute exacerbations of asthma. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(15):1589-1600. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnston SL, Szigeti M, Cross M, et al. ; AZALEA Trial Team . Azithromycin for acute exacerbations of asthma: the AZALEA randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(11):1630-1637. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fisher BT, Lindenauer PK, Feudtner C. In-hospital databases In: Strom BL, Kimmel SE, Hennessy S, eds. Pharmacoepidemiology. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2012:244-258. doi: 10.1002/9781119959946.ch16 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Shared Savings Program. Program Statutes & Regulations. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/medicare-fee-for-service-payment/sharedsavingsprogram/program-statutes-and-regulations.html. February 2018. Accessed April 16, 2018.

- 10.Niewoehner DE, Erbland ML, Deupree RH, et al. ; Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group . Effect of systemic glucocorticoids on exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(25):1941-1947. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199906243402502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gagne JJ, Glynn RJ, Avorn J, Levin R, Schneeweiss S. A combined comorbidity score predicted mortality better than existing scores. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(7):749-759. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Austin PC. Using the standardized difference to compare the prevalence of a binary variable between two groups in observational research. Commun Stat Simul Comput. 2009;38(6):1228-1234. doi: 10.1080/03610910902859574 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.D’Agostino RB., Jr Propensity score methods for bias reduction in the comparison of a treatment to a non-randomized control group. Stat Med. 1998;17(19):2265-2281. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stukel TA, Fisher ES, Wennberg DE, Alter DA, Gottlieb DJ, Vermeulen MJ. Analysis of observational studies in the presence of treatment selection bias: effects of invasive cardiac management on AMI survival using propensity score and instrumental variable methods. JAMA. 2007;297(3):278-285. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.3.278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brookhart MA, Wyss R, Layton JB, Stürmer T. Propensity score methods for confounding control in nonexperimental research. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6(5):604-611. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.113.000359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnston SC, Henneman T, McCulloch CE, van der Laan M. Modeling treatment effects on binary outcomes with grouped-treatment variables and individual covariates. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156(8):753-760. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Normansell R, Sayer B, Waterson S, Dennett EJ, Del Forno M, Dunleavy A. Antibiotics for exacerbations of asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;6:CD002741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thorpe KE, Joski P, Johnston KJ. Antibiotic-resistant infection treatment costs have doubled since 2002, now exceeding $2 billion annually. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(4):662-669. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.White House National action plan for combating antibiotic-resistant bacteria. https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/pdf/national_action_plan_for_combating_antibotic-resistant_bacteria.pdf. Published March 2015. Accessed April 16, 2018.

- 20.President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology Report to the president on combating antibiotic resistance. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/microsites/ostp/PCAST/pcast_carb_report_sept2014.pdf. Published September 2014. Accessed April 16, 2018.

- 21.Schuetz P, Bolliger R, Merker M, et al. Procalcitonin-guided antibiotic therapy algorithms for different types of acute respiratory infections based on previous trials. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2018;16(7):555-564. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2018.1496331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tang J, Long W, Yan L, et al. Procalcitonin guided antibiotic therapy of acute exacerbations of asthma: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:596. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Long W, Li LJ, Huang GZ, et al. Procalcitonin guidance for reduction of antibiotic use in patients hospitalized with severe acute exacerbations of asthma: a randomized controlled study with 12-month follow-up. Crit Care. 2014;18(5):471. doi: 10.1186/s13054-014-0471-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stefan MS, Rothberg MB, Shieh M-S, Pekow PS, Lindenauer PK. Association between antibiotic treatment and outcomes in patients hospitalized with acute exacerbation of COPD treated with systemic steroids. Chest. 2013;143(1):82-90. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-0649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure. Flow Chart With Patients Excluded From the Cohort Analyzed