Key Points

Question

In eyes with macular edema secondary to central retinal or hemiretinal vein occlusion, is switching treatment after a poor response to bevacizumab or aflibercept associated with improvement in visual acuity or central subfield thickness?

Findings

In this secondary analysis of a nonrandomized trial in which 49 patients with central retinal or hemiretinal vein occlusion responded poorly to treatment with bevacizumab or aflibercept, eyes with treatment switched from bevacizumab to aflibercept at month 6 showed improvement in visual acuity and central subfield thickness at month 12. Few eyes had a poor response to aflibercept, and therefore, treatment was switched to dexamethasone in few.

Meaning

Eyes with central retinal or hemiretinal vein occlusion that have a poor response to bevacizumab may benefit after switching to aflibercept treatment; however, the small sample size and lack of controls in this study preclude definitive conclusions.

Abstract

Importance

Information is needed to assess switching treatment in eyes with a poor response to 6 months of monthly administration of aflibercept or bevacizumab for macular edema from central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO) or hemiretinal vein occlusion (HRVO).

Objective

To investigate visual acuity letter score (VALS) and central subfield thickness (CST) changes from month 6 to 12 among eyes with a poor response at month 6 to monthly dosing of aflibercept or bevacizumab in the Study of Comparative Treatments for Retinal Vein Occlusion 2.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This secondary analysis of the Study of Comparative Treatments for Retinal Vein Occlusion 2 (SCORE2) was conducted at 66 private practice or academic centers in the United States. Participants included 49 patients (1 eye from each patient evaluated) with CRVO- or HRVO-associated macular edema and a protocol-defined poor response to aflibercept or bevacizumab treatment at month 6. The first month 6 visit occurred on September 8, 2015, and the last month 12 visit occurred on October 24, 2016.

Interventions

Treatment in eyes receiving monthly aflibercept was switched to a dexamethasone implant at month 6 and, if needed, at months 9, 10, or 11. Treatment in eyes receiving monthly bevacizumab was switched to aflibercept at months 6, 7, and 8, and then to a treat-and-extend aflibercept regimen until month 12.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Change from month 6 to 12 in VALS and CST.

Results

Of the 49 participants at month 6, aflibercept treatment had failed in 14 (6 [43%] women; mean [SD] age, 70.4 [13.0] years). Bevacizumab treatment had failed in 35 patients (16 [46%] women; mean age, 70.0 [13.2] years). In 14 eyes with treatment switched from aflibercept to dexamethasone, the estimated mean change from month 6 to 12 in VALS was 2.63 (95% CI, −3.29 to 8.56; P = .37) and 46.0 μm (95% CI, −80.9 to 172.9 μm; P = .46) for CST. In 35 eyes with treatment switched from bevacizumab to aflibercept, the estimated mean change from month 6 to 12 in VALS was 10.27 (95% CI, 6.05-14.49; P < .001) and −125.4 μm (95% CI, −180.9 to −69.9 μm; P < .001) for CST.

Conclusions and Relevance

Eyes treated with aflibercept after a poor response to bevacizumab had improvement in VALS and CST. Few eyes had a poor response to aflibercept, and therefore, few eyes were switched to dexamethasone. Caution is warranted in interpreting these results owing to the small number of eyes and lack of comparison groups. These factors preclude definitive assessment of whether the switching strategy is superior to maintaining treatment.

This secondary analysis of the SCORE2 study examines the results of treatment switching in patients with central or hemiretinal vein occlusion who responded poorly to 6 months of aflibercept or bevacizumab therapy.

Introduction

The Study of Comparative Treatments for Retinal Vein Occlusion 2 (SCORE2) study demonstrated that, among participants with macular edema associated with central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO) or hemiretinal vein occlusion (HRVO), monthly intravitreal bevacizumab was noninferior to monthly intravitreal aflibercept with respect to visual acuity after 6 months of treatment.1 One key secondary analysis showed no meaningful visual acuity differences at 12 months in a comparison between participants with a good response at month 6 who received a treat-and-extend regimen and those who received monthly injections between months 6 and 12. However, because of wide CIs on visual acuity differences, caution is warranted before concluding that the 2 regimens are associated with similar vision outcomes.2

We report a preplanned secondary analysis of the SCORE2 study in which we analyze visual acuity letter score (VALS) and central subfield thickness (CST) from month 6 to 12 among eyes with treatment switched at month 6 from aflibercept to dexamethasone (referred to as aflibercept treatment failures) or from bevacizumab to aflibercept (bevacizumab treatment failures) because of a protocol-defined poor response at month 6.

Methods

In this secondary analysis of the Score2 study, the first month 6 visit occurred on September 8, 2015, and the last month 12 visit occurred on October 24, 2016. The study was approved by either a site-specific or centralized institutional review board (Chesapeake Institutional Review Board). Participants provided written informed consent prior to screening for eligibility and again before randomization; they received financial compensation to cover travel expenses. The protocol and human participant considerations are described elsewhere.1 This study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.3

A poor or marginal response at month 6 was defined as (1) VALS less than 58 (approximate Snellen <20/80) or VALS improvement of fewer than 5 letters from baseline, and (2) spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) with 1 or more of CST 300 μm or greater (or ≥320 μm on Spectralis; Heidelberg Engineering Inc), presence of intraretinal cystoid spaces, or subretinal fluid.

Patients who experienced aflibercept treatment failure were assigned to receive an intravitreal injection of a dexamethasone, 700 μg, implant at month 6 followed by an as-needed injection of the implant at month 9, 10, or 11. Patients who experienced bevacizumab treatment failure were assigned to receive intravitreal aflibercept at months 6, 7, and 8, and then to a treat-and-extend aflibercept regimen2 until month 12.

Fifteen of 174 participants (8.6%) randomized at month 0 to aflibercept and 39 of 173 participants (22.5%) randomized at month 0 to bevacizumab were classified as having a protocol-defined poor response at month 6. Fourteen of the patients who experienced aflibercept treatment failure switched to dexamethasone and 35 of those who experienced bevacizumab treatment failure were included in a per-protocol analysis reported herein. Patients excluded were 1 patient who experienced aflibercept treatment failure who, at the request of his physician, was treated during months 6 to 12 with aflibercept instead of the protocol-specified dexamethasone and 4 bevacizumab participants who were misclassified as having experienced bevacizumab treatment failures owing to a study software error. Differences between intent-to-treat and per-protocol P values for changes from month 6 to month 12 are minor, with no disagreements as to statistical significance at the .05 level.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical comparisons within aflibercept treatment failures and bevacizumab treatment failures were based on contrasts at month 12 from a normal repeated-measures regression that included all visits that participants attended from months 7 to 12. Temporal autocorrelations were modeled to decline exponentially with the temporal distance between the irregularly spaced actual visit dates. We report observed outcomes, without imputing missing data. We used the sign test to compare macular resolution at month 6 with month 12 in bevacizumab failures (Table).

Table. Visual Acuity and SD-OCT Outcomes at Month 12a.

| Characteristic | No., Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Aflibercept Treatment Failuresb | Bevacizumab Treatment Failuresb | |

| Visual acuity letter score | ||

| Month 0 | 14, 34.4 (15.2) | 35, 49.4 (16.7) |

| Month 6 (presecondary randomization) | 14, 44.9 (15.5) | 35, 52.3 (14.8) |

| Month 12 | 12, 45.1 (15.4) | 33, 62.9 (18.6) |

| Change from month 6 | 12, 3.0 (8.4) | 33, 9.9 (15.8) |

| Primary outcome | ||

| Model-based change from month 6 to 12, mean | 2.63 | 10.27 |

| P value | .37 | <.001 |

| 95% CI | −3.29 to 8.56 | 6.05 to 14.49 |

| SD-OCT central subfield thickness, μm | ||

| Month 0 | 13, 693.2 (280.5) | 35, 675.2 (261.1) |

| Month 6 (presecondary randomization) | 12, 273.4 (150.8) | 35, 417.7 (178.8) |

| Month 12 | 10, 288.9 (146.8) | 32, 291.6 (185.0) |

| Change from month 6 | 8, 51.4 (171.2) | 32, −132 (181.5) |

| Model-based change from month 6 to 12, mean | 46.0 | −125.4 |

| P value | .46 | <.001 |

| 95% CI | −80.9 to 172.9 | −180.9 to −69.9 |

| Resolution of macular edema | ||

| Month 6 (presecondary randomization), No. (% with resolution) | 2 of 14 (14) | 0 of 35 (0) |

| Month 12, No. (% with resolution) | 2 of 10 (20) | 7 of 32 (22) |

| OR (month 12/month 6) | 1.5 | Infinity |

| Model-based OR (month 12/month 6) | 1.85 | c |

| P value | .57 | .02 |

| 95% CI | 0.22 to 15.67 | |

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; SD-OCT, spectral-domain optical coherence tomography.

Exclusions included 1 participant who experienced aflibercept treatment failure who was, at the request of his physician, treated during months 6 to 12 with aflibercept instead of the protocol-specified dexamethasone. Four bevacizumab participants were misclassified as having experienced bevacizumab treatment failure owing to a study software error.

P values for the intent-to-treat analyses are similar (P = .36, .70, and .58) for patients who experienced aflibercept treatment failures, and (<.001, <.001, and <.002) for those who experienced bevacizumab treatment failures, for the change from month 6 to 12 in visual acuity letter score and SD-OCT central retinal thickness and resolution of macular edema outcomes, respectively.

The month 12/month 6 OR of resolution was undefined for patients who experienced bevacizumab treatment failures because there were no resolved cases at month 6. Of the 35 unresolved cases at month 6, 3 were missing, 25 were unresolved, and 7 were resolved at month 12. Under the hypothesis that nonmissing patients who changed resolution status were just as likely to resolve at 6 months as at 12 months, the 2-tailed P value for the observed outcome is <.02 by the sign test.

Statistical analyses were performed with SAS, versions 9.3 and 9.4 (SAS Inc). Statistical analyses included data available as of July 10, 2017. All testing was 2-tailed at a significance level of .05.

Results

Aflibercept Treatment Failure

The mean (SD) age of the participants at month 6 was 70.4 (13.0) years; 6 (43%) were women, and 1 patient (7%) had an HRVO. Month 0 mean (SD) VALS was 34.4 (15.2) (approximate Snellen 20/200) and month 6 mean VALS was 44.9 (15.5) (approximate Snellen 20/125), which represents an improvement of 10.5 (11.8) letters (Table). Month 0 mean (SD) SD-OCT CST was 693 (281) μm, and month 6 mean SD-OCT CST was 273 (151) μm, which was an improvement of 411 (256) μm.

From month 6 to 12, a mean (SD) of 1.8 (0.6) dexamethasone treatments per participant were administered. Mean number of days between consecutive treatments was 93 (26). Eighty-eight percent of the injections occurred within 7 days of the target treatment date. Twelve of the 14 participants (86%) completed the month 12 visit.

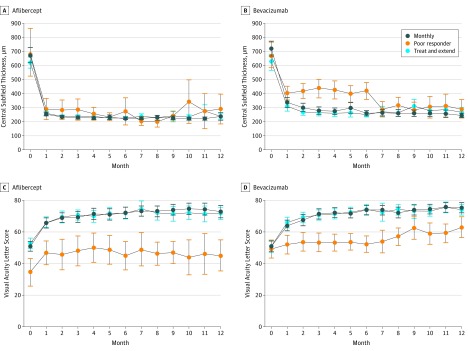

Estimated mean change from month 6 to 12 in VALS was 2.63 (95% CI, −3.29 to 8.56; P = .37) and 46.0 μm (95% CI, −80.9 to 172.9; P = .46) for CST. At month 12, VALS was 45.1 (95% CI, 35.3 to 54.9), which was significantly lower than the VALS in the corresponding participants with a good response at month 6 who received a treat-and-extend regimen or received monthly injections between months 6 and 12 as evidenced by nonoverlapping 95% CIs (Table and Figure).

Figure. Mean Central Subfield Thickness (CST) and Visual Acuity Letter Score (VALS) Over Time in Treatment Groups Assigned at Month 6 to Monthly, Treat and Extend, or Poor Responder (ie, Failure) Status.

Mean CST and VALS in participants receiving aflibercept (A and C) and bevacizumab (B and D). Bevacizumab treatment failures that switched to aflibercept treatment experienced a large decrease in CST during months 6 to 7, and an increase of approximately 10 in VALS score from month 6 to 12. Poor responders had worse mean VALS than other groups throughout the study. Aflibercept treatment failures that switched to dexamethasone treatment had lower mean VALS at month 0 than did bevacizumab treatment failures. Treatment failures are not randomized groups. Error bars indicate 95% CI.

Bevacizumab Treatment Failure

The mean (SD) age of participants at month 6 was 70.0 (13.2) years, 16 (46%) were women, and 4 patients (11%) had an HRVO. Month 0 mean VALS was 49.4 (16.7) (approximate Snellen 20/100), month 6 mean VALS was 52.3 (14.8) (approximate Snellen 20/100), which was a change of 2.8 (11.7) from baseline (Table). Month 0 SD-OCT CST was 675 (261) μm, and month 6 mean SD-OCT CST was 418 μm (179), which was an improvement of 257 (300) μm.

From month 6 to 12, a mean (SD) of 5.1 (1.3) aflibercept treatments per participant were administered. Mean number of days between consecutive treatments was 32 (4.5). A total of 96% of injections occurred within 7 days of the target treatment date. Thirty-three of the 35 participants (94%) completed the month 12 visit.

Estimated mean change from month 6 to 12 in VALS was 10.27 (95% CI, 6.05 to 14.49; P < .001) and −125.4 μm (95% CI, −180.9 to −69.9 μm; P < .001) for CST. At month 12, VALS was 62.9 (95% CI, 56.3 to 69.5), which was significantly lower than the VALS in the corresponding participants with a good response at month 6 who received a treat-and-extend regimen or monthly injections between months 6 and 12, as evidenced by nonoverlapping 95% CIs (Table and Figure).

Discussion

The literature is replete with studies of switching treatment strategies for eyes with macular edema due to retinal vein occlusion that have not responded well to antivascular endothelial growth factor therapy.4,5,6,7,8,9 Except for the review by Pfau et al,9 these prior analyses suggest that a switch (usually to aflibercept) can result in mildly improved visual outcomes and CST. The validity of these conclusions is hampered by a lack of control groups, the retrospective nature of reviews, and variable treatment regimens before and after the treatment switch.

Supporting a potential true association in the SCORE2 study between the switch to aflibercept among patients who experienced bevacizumab treatment failure and improvement are the magnitude of the mean change (mean of ≥10 in VALS from month 6 to 12, which exceeds the magnitude of change seen in most previous switching studies4,5,6,7,8,9) and the observation that the large CST response in the patients who experienced bevacizumab treatment failure occurred shortly after the switch (between month 6 and 7). For eyes with a poor response to aflibercept and then treated with dexamethasone, there was no such improvement in VALS or CST.

Limitations

The present study has limitations. Although it was prospective, it lacked control groups. Ferris et al,10 in a simulated switching study using Comparison of AMD Treatments Trials and Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network protocol I study data, describe how regression to the mean or time effects can cause an apparent mild improvement in visual acuity and CST following a simulated medication switch that, in the absence of a control, can be confused with a treatment effect. Zarbin et al11 presented similar conclusions. Using SCORE2 data, we performed several simulated switching studies at different time points and found that the degree of simulated visual acuity change and CST change was similar to the change in the studies reviewed above, but smaller in magnitude than what we observed in the bevacizumab treatment failure group switched to aflibercept from month 6 to 12.

Conclusions

In the SCORE2 study, the small sample size (few eyes were deemed poor responders), lack of randomization, masking, and control groups, and potential regression to the mean preclude definitively determining whether the switching strategy is superior, similar, or inferior to maintaining treatment. For eyes with a poor response to aflibercept and treated with dexamethasone, there was no significant improvement in VALS or CST, but the same cautions discussed above apply to the interpretation of this finding.

References

- 1.Scott IU, VanVeldhuisen PC, Ip MS, et al. ; SCORE2 Investigator Group . Effect of bevacizumab vs aflibercept on visual acuity among patients with macular edema due to central retinal vein occlusion: the SCORE2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317(20):2072-2087. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.4568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scott IU, VanVeldhuisen PC, Ip MS, et al. ; SCORE2 Investigator Group . Comparison of monthly vs treat-and-extend regimens for individuals with macular edema who respond well to anti-vascular endothelial growth factor medications: secondary outcomes from the SCORE2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018;136(4):337-345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Medical Association World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Konidaris VE, Tsaousis KT, Al-Hubeshy Z, Pieri K, Deane J, Empeslidis T. Clinical real-world results of switching treatment from ranibizumab to aflibercept in patients with diabetic macular oedema. Eye (Lond). 2017;31(11):1629-1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen MN, Houston SK, Juhn A, et al. Effect of aflibercept on refractory macular edema associated with central retinal vein occlusion. Can J Ophthalmol. 2016;51(5):342-347. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2016.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Papakostas TD, Lim L, van Zyl T, et al. Intravitreal aflibercept for macular oedema secondary to central retinal vein occlusion in patients with prior treatment with bevacizumab or ranibizumab. Eye (Lond). 2016;30(1):79-84. doi: 10.1038/eye.2015.175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eadie JA, Ip MS, Kulkarni AD. Response to aflibercept as secondary therapy in patients with persistent retinal edema due to central retinal vein occlusion initially treated with bevacizumab or ranibizumab. Retina. 2014;34(12):2439-2443. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000000238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lehmann-Clarke L, Dirani A, Mantel I, Ambresin A. The effect of switching ranibizumab to aflibercept in refractory cases of macular edema secondary to ischemic central vein occlusion. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2015;232(4):552-555. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1545783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pfau M, Fassnacht-Riederle H, Becker MD, Graf N, Michels S. Clinical outcome after switching therapy from ranibizumab and/or bevacizumab to aflibercept in central retinal vein occlusion. Ophthalmic Res. 2015;54(3):150-156. doi: 10.1159/000439223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferris FL III, Maguire MG, Glassman AR, Ying GS, Martin DF. Evaluating effects of switching anti–vascular endothelial growth factor drugs for age-related macular degeneration and diabetic macular edema. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;135(2):145-149. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.4820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zarbin M, Hill L, Tsuboi M, Stoilov I A simulated switching study from the HARBOR trial of ranibizumab treatment for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Presented at the 41st Annual Meeting of the Macula Society; February 23, 2018; Beverly Hills, California. [Google Scholar]